Two black-figured amphorae in the Museum are here for the first time adequately illustrated. One, Figs. 68 and 69, has been published before, but with illustrations which do scant justice to the beauty of the paintings. The other has never been published, although Adolf Furtwaengler included a brief description of it in his notes on American museums and pointed out that its style was related to that of Exekias. Both vases were put together from fragments found in tombs at Orvieto, and as in the case of other vases made up from pieces from these tombs, many parts are lacking. The missing parts, however, are not now so extensive as heretofore, for in the first restoration of these vases which was made shortly after the fragments reached the Museum in 1898, several fragments were overlooked. Of these the most important were the pieces composing the two central figures of the scene in Fig. 66, a fragment with two letters from the inscription at the left of Fig. 65, and one from the lower part of the figure at the right of Fig. 68. These were discovered among the unclassified fragments from the Orvieto tombs and introduced into their proper places.

Museum Object Number: MS3497

Image Number: 183147

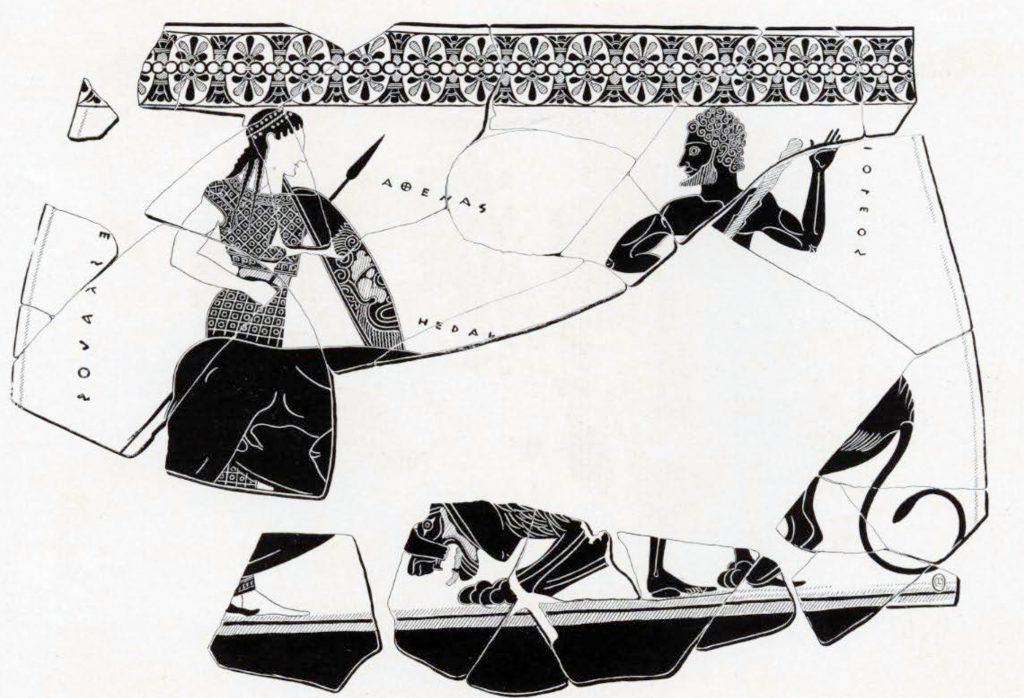

Of the two painted panels on the amphora (Figs. 65 and 66), the one depicts the familiar story of Herakles’ combat with the Nemean lion, the other a scene which is exceedingly rare and difficult to interpret. The picture of Herakles’ exploit is arranged in the old-fashioned manner, whereby the hero is represented with one knee bent almost to the ground and the contour of his straining back making a straight horizontal line across • the center of the panel. Athena stands stiffly by with spear and shield. The shield shown. in profile is ornamented with a Gorgon’s head, which the artist in his inability to foreshorten has cut just in half. Iolaos, Herakles’ helper, holds the hero’s knotted club and raises his left hand in token of his excitement. His hair is rendered by neat rows of spirals, and his eye and beard are of the form chiefly used by painters of the black-figured style in the closing years of the sixth century. Each figure is identified by an inscription. Of Herakles’ name only five letters remain, written horizontally above his back. The name of Athena is written in the genitive and with a cross-barred theta which is supposed to be a lineal descendant of the old pictographic sign of a wheel. Along the left of the panel is a perpendicular inscription announcing that someone whose name ends in ες is lovely. A strange interpolation, it seems, in a picture of Herakles’ exploit, but this habit of vase painters is well known. It was the fashion to inscribe upon vases the name of some beautiful youth who was at that moment the favorite in the city of Athens. The name of the boy whose beauty is here celebrated can only be surmised. It was apparently a short name and of the short names ending in ες which appear on vase paintings of this period one might choose Pyles or Teles or several other names, but certainty is impossible.

Museum Object Number: MS3497

Image Number: 183146

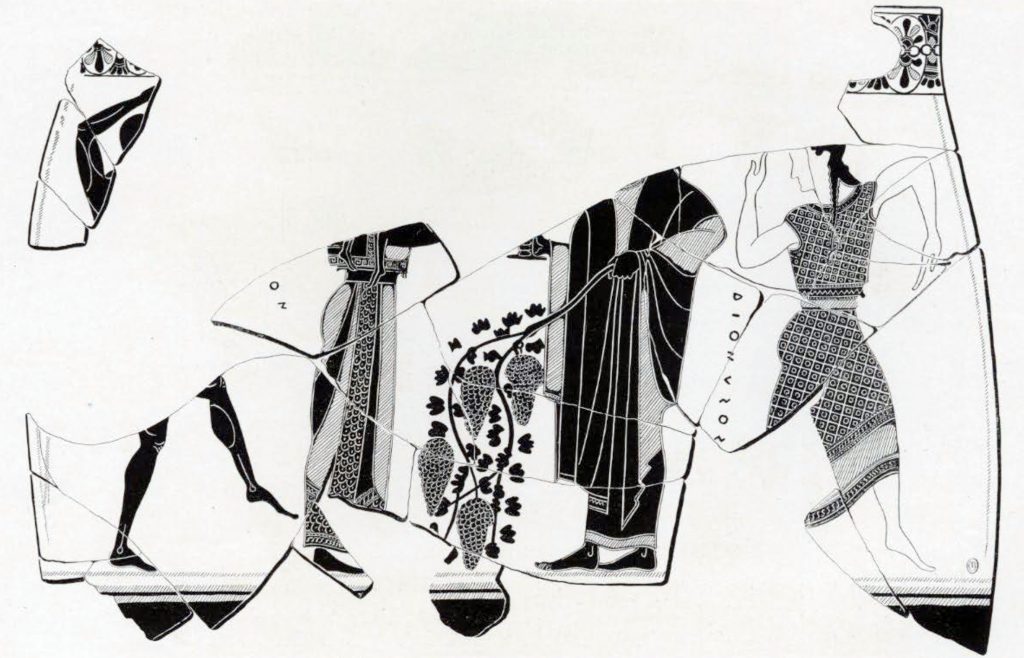

The interpretation of the scene on the other side of the vase involves an archaeological problem the solution of which is not yet found. It is a Dionysiac scene which is here represented. The figure of the god himself may be recognized both by the trailing branch of vine weighted with full clusters of grapes and by the inscription on his right. The agitated maiden behind him can hardly be other than a Maenad and the figure on the extreme left is a satyr, the tip end of whose tail may be traced in the slight line of purple just below the break in the lower left hand corner of the apnel. To the right of this figure are the last two letters, ον, of an inscription which might be restored as Εχον, or any other of the names in ον, by which satyrs were known.

But it is the figure of the woman or goddess between Dionysos and the satyr which is the chief concern. She stands with her elbows out and her forearms level and below her arms may be seen two small pairs of legs. The question is, who is she and who are the twins? There are so few vases in which such a figure occurs that it is no arduous task to enumerate them. They are as follows.

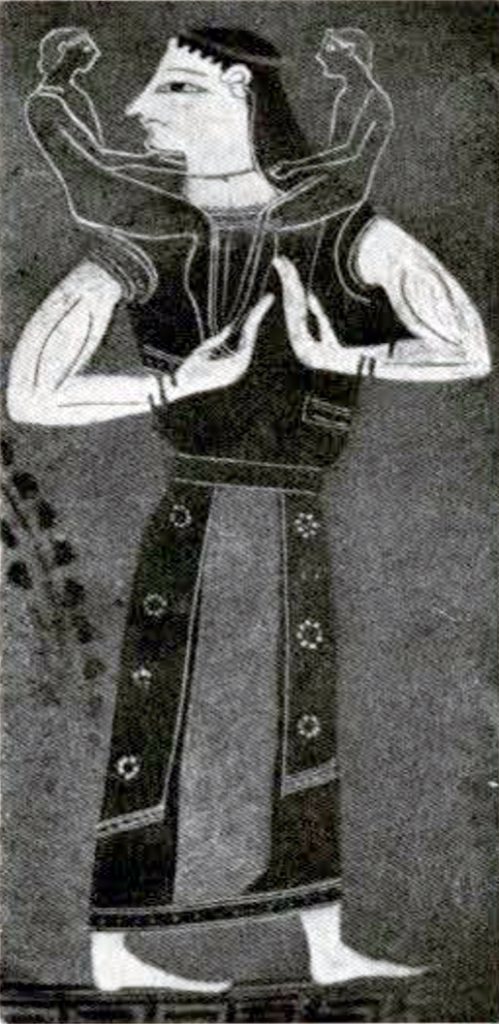

- Amphora in the British Museum, published in Gerhard, Auserlesene Vasebilder, pl. 55. There are four figures in the scene, Hermes, Dionysos with a branch of vine and a drinking horn, a woman or goddess with two children on her arms, and a satyr. The figure of the goddess is reproduced in Fig. 67.

- Skyphos, in Würzburg, published id., pl. 56. Here the figures are Hermes, two satyrs, Dionysos, and a woman with one child in her arms.

- Vase in the Etruscan Museum of the Vatican, published in Museo Gregoriano, II, pl. 39, 1, Hermes, Dionysos and a woman with two children.

- Amphora in the Louvre, published in Élite ceramique, II, 2. A woman or goddess with two children stands between two columns, on one of which is an owl.

- Vase published in Micali, Storia, pl. 85, 1. A woman with two children stands between Dionysos and a satyr.

- Fragment from the Acropolis in the Acropolis Museum, published in Graef, Die antiken Vasen von der A kropolis zu Athen, pl. 60, 3. Here a procession of gods is represented and beside Dionysos stands a goddess who is named by an inscription, Aphrodite. Only half of this figure is preserved. Part of one child remains and it is presumable from the position of the figure that two children were carried originally.

- An unpublished fragment from the Acropolis, Athens, in which Aphrodite is represented with two children on her arms and this time they are inscribed Ιμερος and Ερως or Love and Longing.

In order to have the data quite complete for deciding who this enigmatical madonna is, there should be borne in mind a passage in Pausanias (Description of Greece, V, 18, 1) where he is describing the chest of Cypselus. “In the second field on the chest we will begin to go round from the left. A woman is represented carrying a white boy asleep on her right arm: on her other arm she has a black boy who is like one that sleeps: the feet of both boys are turned different ways. The inscriptions show, what it is easy to see without them, that the boys are Death and Sleep and that Night is nurse of both.”

From all this it may be gathered, first, that more than one goddess was represented with two children (or more rarely one) as attributes, and second, that in scenes where neither the goddess nor the children are identified by inscriptions Dionysos and members of his train are with one exception present.

Miss Jane Harrison of Cambridge has argued that the process of “The Making of a Goddess” was from the general to the specific, that in early religion there was a mother goddess who “was an attribute become a personality,” a Kourotrophos or nurse Child Rearer, and that later when her personality had faded her epithet of Kourotrophos and her functions of Child Rearer were usurped by other and more popular goddesses. She cites vase paintings as evidence for the ” slow differentiation and articulation of theological types.” “At first all is vague and misty; there is, as it were, a blank formula, a mother goddess characterized by twins. If we give her a name at all she is Kourotrophos. As her personality grows she differentiates, she is Aphrodite with Eros and Himeros, she is Night with Sleep and Death. When Apollo and Artemis came from the North they became the twins par excellence, and they were affiliated to the old religion; the mother as Kourotrophos became Leto with Apollo and Artemis.”

The argument is not as convincing as it would be if the goddess were not named Aphrodite on the earliest of the fragments preserved. Moreover, the constant association of this early Madonna with Dionysos and his train implies a particular goddess connected with the Dionysiac cult. It may be that the goddess here depicted is Semele, mother of Dionysos, who, as Miss Harrison herself has shown, is in essence the Earth-Mother. In later art Mother Earth has very usually two children as attributes, so that this identification is at least possible, although it cannot be proved.

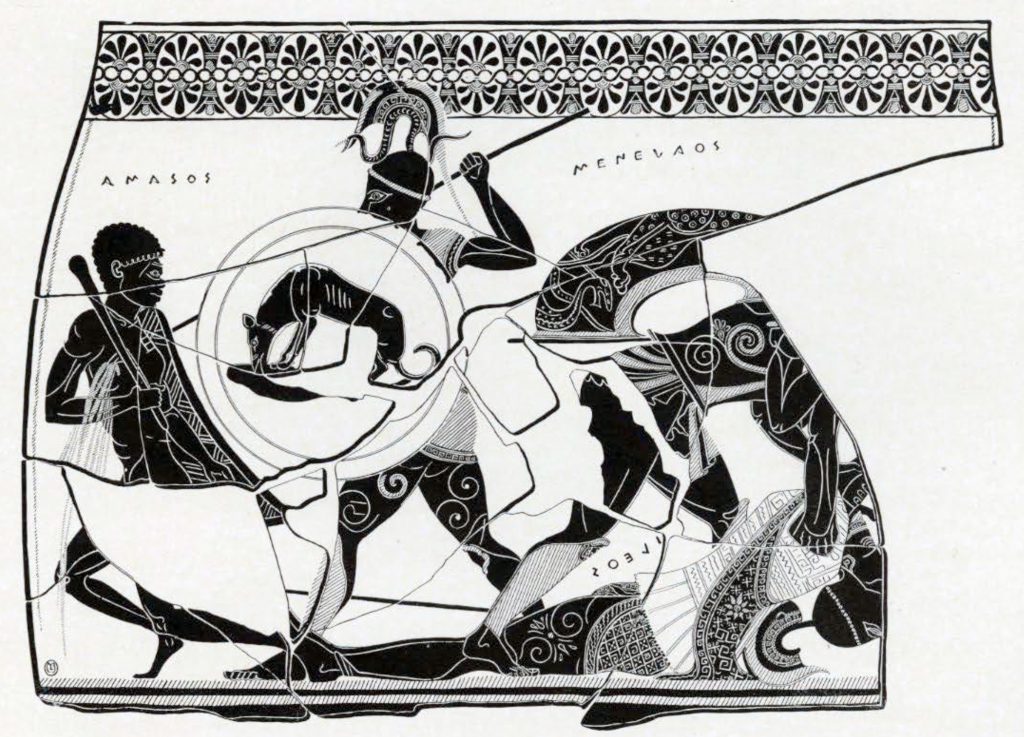

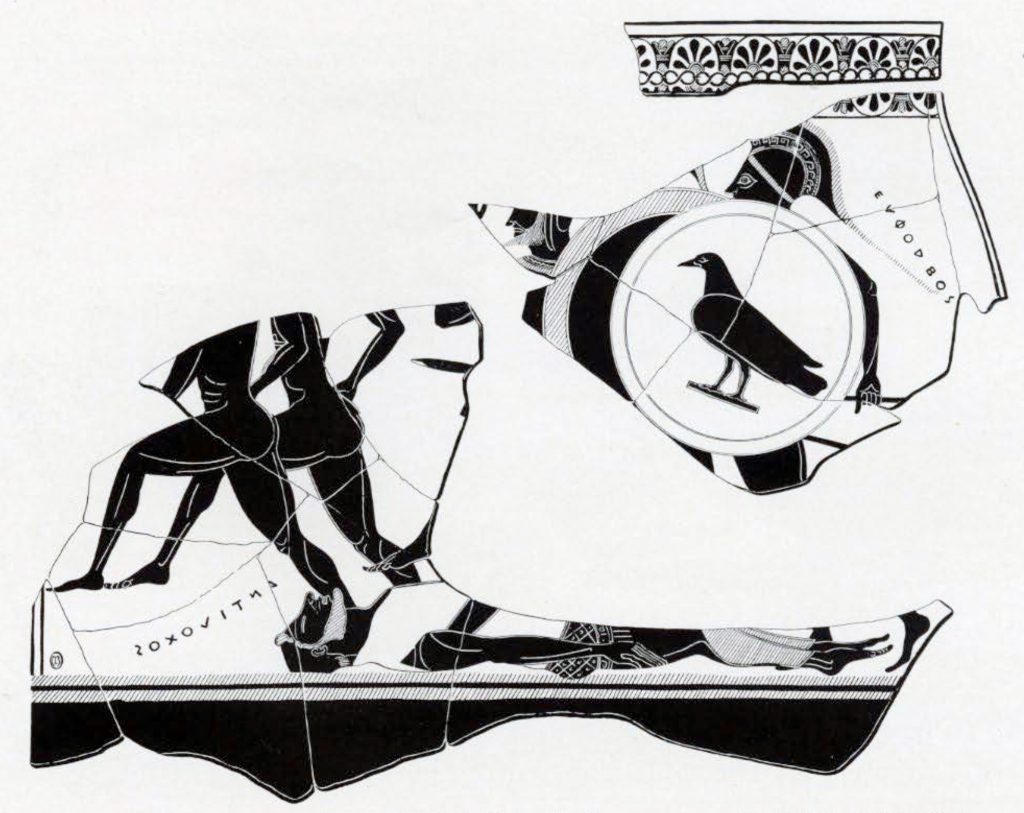

Of the other amphora, the paintings of which are reproduced in Figs. 68 and 69, no detailed description is necessary, inasmuch as it has already been described both by Professor Bates and by Adolf Furtwaengler. On the one side Ajax rescues the body of Achilles while Menelaos transfixes with his spear one of the Ethiopian followers of Memnon, whose name—Amasos for Amasios, the genitive of Amasis—is written above his head. The master of this vase was a realist. He delighted to show the blood spurting from the negro’s wound, the “undoing of his knees” and the limp and heavy weight of the lifeless corpse. He delighted in the ornaments of armor, in the devices of their shields, in the little gorgons’ heads on Ajax’s greaves and above all in the lovely Ionic volutes and finely wrought patterns of the thorax. Three of the warriors are identified by inscriptions. Above the prostrate body is Αχίλεος “of Achilles.” Μενελαος is written parallel to the spear in the hands of the central figure, and Αμασος for ‘Αμασιος, above the head of the falling Ethiopian.

On the reverse a prostrate body forms again the center of the scene. It is identified by the inscription ‘Αντιλοχος. Of the three warriors who are driving off his murderers, only the last one has a name, ΕύΦορβος.

The vase, in Furtwaengler’s judgment, is to be ascribed to the painter Exekias. It is also to be associated with an amphora in the British Museum, on which one of Memnon’s followers is named with an inscription,

E. H. H.

Museum Object Number: MS3442

Image Number: 2753

Museum Object Number: MS3442

Image Number: 2754, 183148