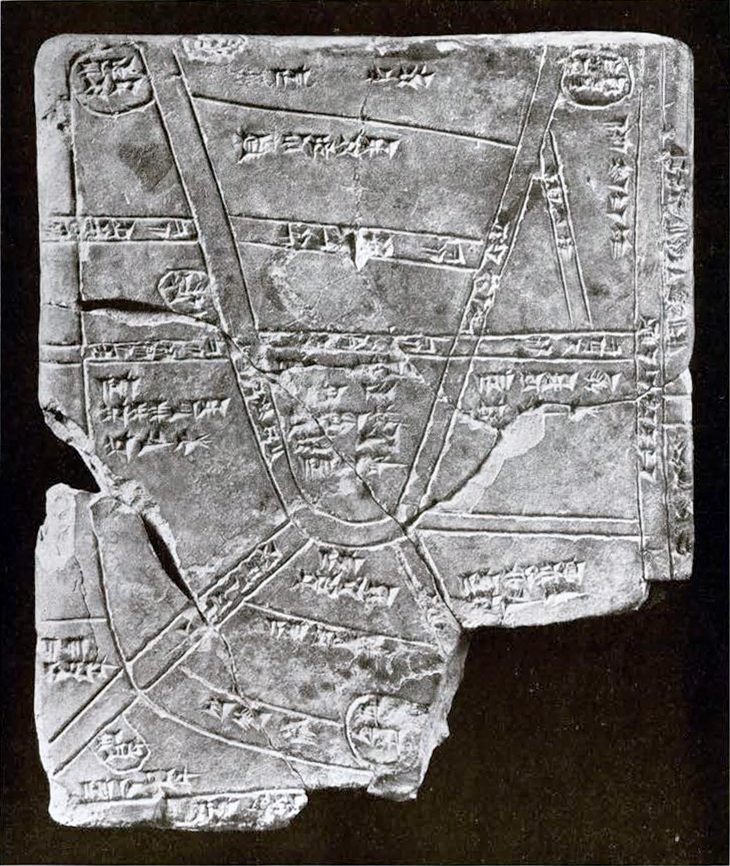

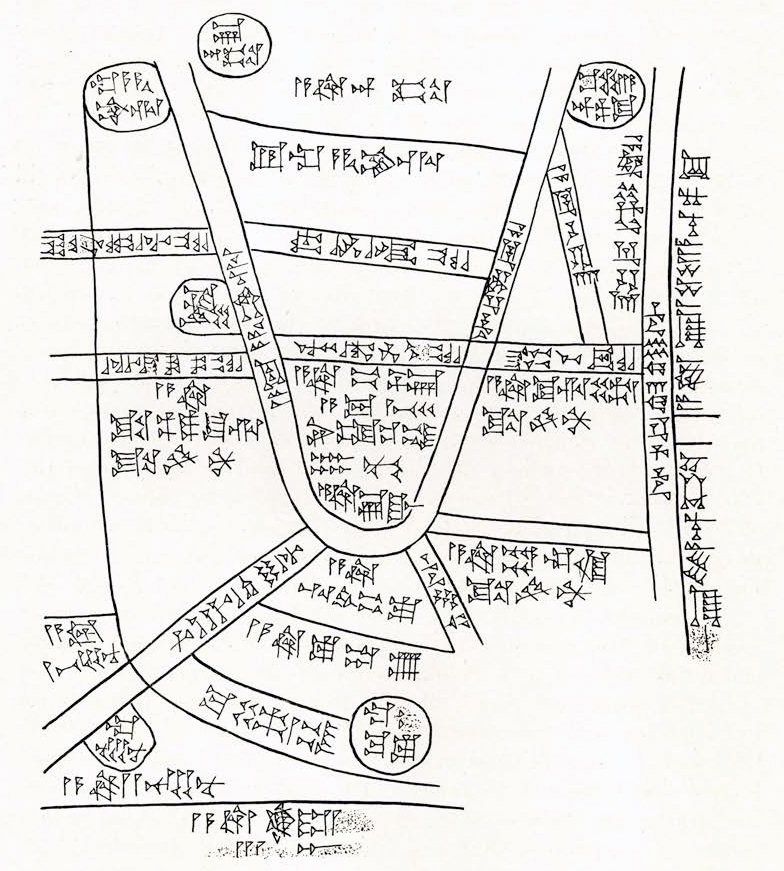

Among the collections in the Babylonian Section of the Museum is a clay tablet upon which an ancient engineer drew a map showing canals, villages and fields. It shows part of an agricultural area near the city of Nippur and was made in the Cassite Period about 1,500 years B.C. The rural life of ancient times in this historic land has here a visual commentary, and we see how the peasants lived together in villages, having village commons for their flocks and a municipal marsh to furnish a most necessary article of domestic life, the cane reed. Assuming that the orientation of the map is the ordinary one employed in other Babylonian maps, the reader will be able to trace the several features of the country and their details.

Museum Object Number: B13885

Image Number: 6505

The skeleton of the plan is made by the canal which enters from the northeast corner of the district, flows south-southwest and turns in a rough parabolic curve to retreat at the same angle toward the north-northwest. At the center of the district marked by the end of the parabola enter from the southeast and southwest corners two canals which unite with the main canal. In the extreme northeast corner is a town Bit-Kar iliuNusku, indicated by a small circle and an inscription. The northeast wing of the canal on which this town lay is called Nar-bilti or “Canal of the burden,” a name which refers to the agricultural products brought to and fro upon the canal. This name, and others about to be discussed, show that these canals were arteries of trade as well as streams to supply the fields with water. The town Kar-Nusku is mentioned in temple accounts of the city of Nippur as supplying sheep and grain for the support of the temple priests. In the northwest corner on the left branch of the canal is the town âluHamri, also mentioned in the accounts of the temples at Nippur. Therefore the northwest branch of the canal bears the name Nar-Hamri. (According to references in Assyrian inscriptions hamru designates a place where the cult of the fire god was established.) The canal entering from the southwest is called the “Irrigation of Bêlšunu” (nam-gar Bêlšunu), because it supplied the estate of Bêlšunu with water. This estate lay outside the limits of the map. Unfortunately the southeast section is broken, but the inscription on the canal which enters from this region begins nam-gar, or irrigation, which shows that it also supplied water to the estate of some land owner whose property lay in this region.

Geographically and probably essentially the point of chief interest in the mind of the map drawer is the field which occupies the cone-like space at the end of the parabola, which is also the center of the map. Their field bears the inscription “Field between the canals, the contents (?) are eight gul (a measure of area in the Cassite and Assyrian inscriptions) field of the palace.” Therefore the map maker really wished to give an accurate drawing of the field belonging to the royal estates and we may assume that he did his work at the king’s injunction and that the tablet has come to us from the royal archives of Nippur. The Cassite kings nominally held court at Babylon as the capital of Babylonia, but their favorite residence appears to have been at Nippur. North of this field passes between the Nâr-bilti and the Nar-Hamri the waterway a-tap [ ]—kur-ru-ti (?). Still further to the north is a second cross waterway a-tap ša-te-e or “stream that gives to drink.” The field between these waterways bears no inscription. The land lying north of this cross canal is called the “Marsh land of the city Hamru.” In the economic life of ancient Babylonia the marshes formed an essential factor and were indispensable in each district, since they supplied reeds. The reed was used for making baskets, household furniture, firewood, hedges and even for the writing stylus. It must be remembered that forests in our sense of the term were unknown in southern Babylonia, hence the reed which grew to enormous size largely supplanted wood in the economic life of the Sumerians and Babylonians. Separated by a line from this public marsh land, owned by the village Hamru, is the large “Field of Marduk” in which lay to the north opposite Hamru and off the north edge of the map the village Bit-iliuMarduk, or “House of Marduk.” Perhaps a temple of this god stood there; in any case this large field in the northern part of the district belonged to the temple estate which supported the cult of Marduk, either a local cult or the cult of the great temple far away in Babylon.

Across the canal to the east of the field of the palace is the “Field Ku-ri-li of the barû priest,” and on the other side to the west is a much larger field called “Field of the table of the barû priest.” The barû priest was the seer of the Babylonians, whom they invariably consulted about all future events. This learned priesthood was attached to all the great temples and, as we see here, owned valuable landed estates. The idea of a state supported order of seers seems preposterous to us, for divination is considered illegal, but Babylonian religion was supercharged with magic and mystery. Kings and laymen undertook no important tasks, launched no important ventures without consulting these sages of the liver omens, of oil omens and of every conceivable kind of divination. They formed an important part of the priesthood and hence we find them on our map in possession of estates more valuable than those of the king himself. To the north of the Field of Kurili passes the cross canal Nar-battum, or “Canal at the side,” a name also given to a waterway passing from the Narbilti southward into this cross canal. The long field thus cut off by these two “Side Canals” on the northeast is called the “Field of the boundary” (ikil la-ma-tum). Bounding the map along the eastern edge is a canal running straight north to south called “Irrigation of Bur-rim-maš-hu,” a phrase obscure. Beyond the limits of the map on the east are two extensive fields, the one on the north having the name “Field of Bit Kar-Nusku,” that is, field belonging to the village Bit Kar-Nusku, which lies in adjacent territory. The name of the village really means “House of the man Kar-Nusku,” being named after a wealthy citizen. According to our map the field was a kind of municipal common. South of this field lies the “Field of Bit Nadin-Marduk,” also a municipal property.

Occupying the truncated cone shaped space south of the field of the palace at the center of the map is the field Mut-bi-lu, which probably means dry or arid land. South of this field between the canals which enter from the lower corners of the map is the field Lu-du-u, a word of unknown meaning, perhaps a field full of pits or old brick quarries. In the southern edge of this field is the village [ ] ba-lu, and crossing the plane of the map from this village westward to the canal of Bêlšunu, is a wide lane called Ba-li-tum, probably non est, that is the land claimed by nobody and used as a highway. South of this is a triangular shaped field belonging to a man Qatnu, in which is located a village which also bears his name. The same Qatnu owns a field across the canal of Bêlšunu to the west. Beyond the southern limit of the map is the field of Har-ra [ ]. To the east of the field Mutbili across the canal is another part of the lands belonging to the barû priests of divination. It has the inscription “Field of the gate of the city” (ikil-Bâb-âli-ki).

It remains to conduct the reader to the northwestern part of the district. Here in the extreme corner is the village Hamri already mentioned situated in a field which bears no name, perhaps the municipal property. South of this area is the field in which we find a village with a curious name Tîl-amel-haššâ, or “Hill of the Fifty men.” The local history of this town which would elucidate its interesting name is unknown. The field itself bears no inscription and was probably a village common also. A small canal (a-tap-hu-un-[ ]-i) separates the two village properties just described. The large field of the “table of the barû priest” is bounded on the north by the cross canal a-tap paššuri, or “canal of the table.” These names refer to the properties settled by royal decree upon this religious order for the support of their table; in precisely the same way certain lands in Europe became the property of monastic orders in the Middle Ages, being destined to provide food for the table of the order. The institution still survives in modified form in the charters of the older English universities.

The map also throws a welcome light upon an obscure law in the great law code of Babylonia which bears the name of Hammurapi. In the column XV lines 65 following, we have a reference to the custom of blowing a horn at the village gates to notify the shepherds on the plains that the grazing season was over. These rural villages in which the peasants congregated from the surrounding plain appear to have been so arranged that the village buglers were able to make the shepherds and farmers hear the sound of the horn in every part of Babylonia. The map will suffice to show how carefully the walled villages were assigned to the adjacent rural districts.

S.H.L.