Revelation of future events by dreams formed an important discipline in the ancient science of divination. The subject was treated at great length by the professors of Greek divination, Artemidorus of Daldis having devoted five books to this subject alone under the title Onirocritiques, or the Interpretation of Dreams. The Greeks regarded the psychological phenomena of dreams as direct revelations from the gods, provided always that the mental preoccupations or physical condition of the dreamer did not interfere to entangle the soul in mortal influences. Dreams are the sons of night and the brothers of sleep, said Hesiod. The classical peoples generally distinguished the oracular source of dreams from all other means of divination. The dark-winged spirits of dreams came to men only in the night, hence their native land was the shades of the lower world. They are the children of Gaea, or Earth, said Euripides, and in this view the mystic Pythagoreans concurred. All other revelation fell under the patronage of Apollo, god of light, he who sees the secrets of all things.

Image Nyumber: 6728

Therefore in dreams it is the deities of the lower world that reveal the future, whereas hepatoscopy or divination by the interpretation of signs on animals’ livers, astrology and other favorite methods of disclosing the intentions of the gods fall to the patronage of the powers of light.

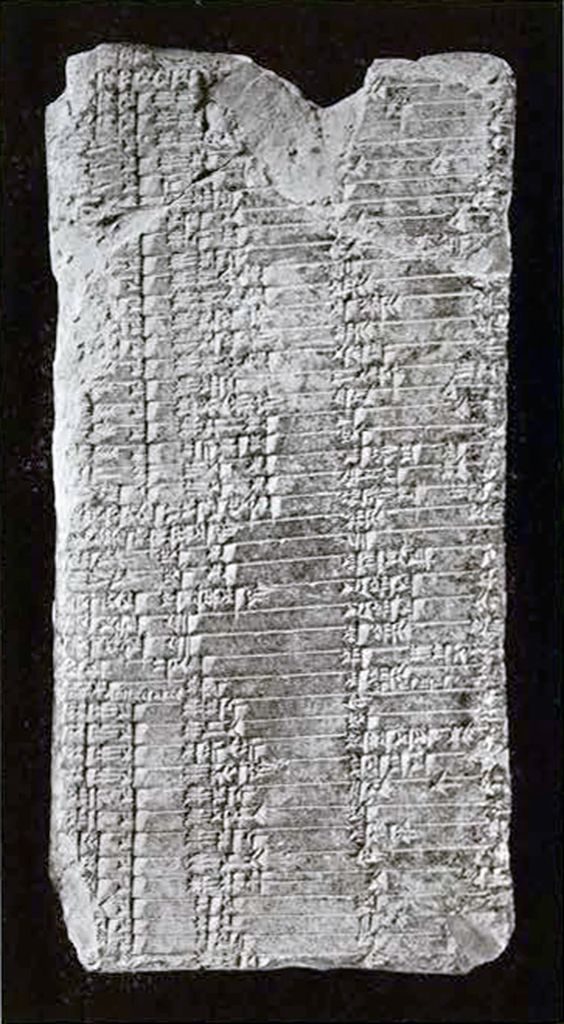

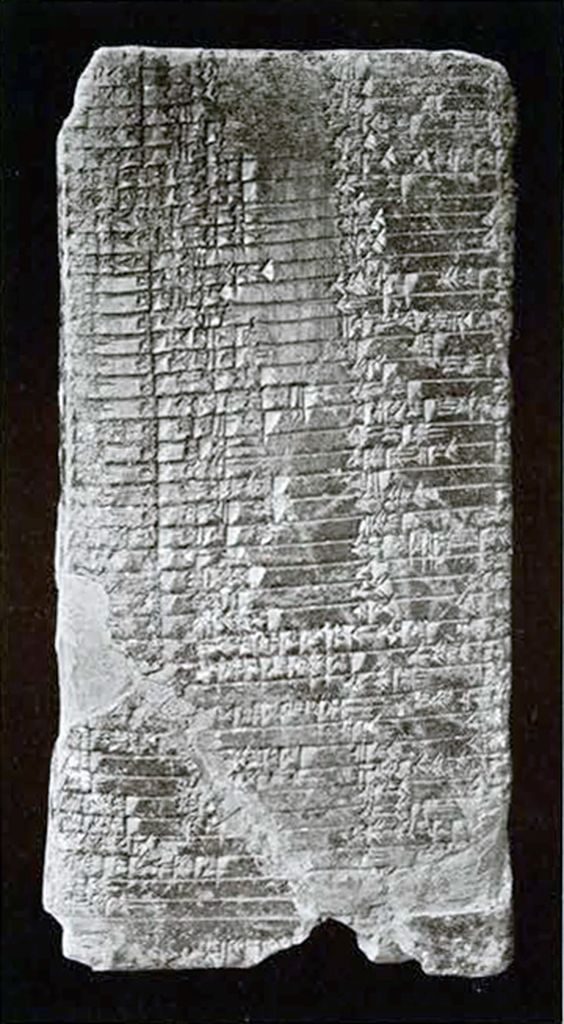

In antiquity Babylonia received universal recognition as the home of the oracular sciences. Here astrology and liver divination attained a development and influence unparalleled. Cuneiform literature is already equipped with an extensive corpus of texts devoted to these mystic subjects which led on the one hand to the scientific development of astronomy and on the other to the study of anatomy. Extensive works on teratoscopy or the interpretation of extraordinary events, lecanomancy or divination by omens taken from the movements of liquids in cups, are known. Up to the present, however, only fragmentary documents of the great cuneiform series on oniromancy have been recovered; these belong to the Asurbanipal Library, excavated at Nineveh and now in the British Museum. The tablets on which it is actually stated that the phenomena described were seen in dreams are not numerous. But a number of oracular tablets have been classified as dream omens, since their contents point obviously to that conclusion. For this reason the writer has classified a remarkable tablet in the University Museum as one of those on which the Babylonians of the time of Moses, or the Cassite period, wrote down their ideas concerning things seen or done in dreams. The tablet, still in almost perfect condition, belongs to about the fifteenth century B.C. At the end the scribe has written the note “Altogether there are 86 lines (or omens).

The sun god Shamash in Babylonia, like Apollo among the Greeks, presided over the mystic disciplines of divination as he did over the institution of laws and their application. Although there is a remnant of evidence to connect the land of dreams with Enlil the earth god in Babylonia, nevertheless this ancient association disappeared and under the influence of the more popular oracular methods of Shamash, this mystic function of the seers came also under the patronage of the great god of light. The goddess of dreams is the daughter of the sun god, said the Sumerians, and a god of dreams was an attendant in the courts of the sun. In the history of Sumer, Babylonia and Assyria the records have preserved accounts of royal dreams in which the mother goddess Ishtar sometimes appears in person before the king, announcing plainly the course of events.

Image Number: 727

Early Hebrew tradition also preserves dreams in which the Hebrew God himself appeared to Jacob, Laban and Solomon, granting them direct oracular instruction. Visions of that kind required no interpretation and were considered direct messages from the gods. The earliest dream vision recorded in cuneiform is the famous symbolic scene which appeared by night to Gudea, Sumerian priest king, who ruled at Lagash about 2700 B.C. In this dream, which appears to have occurred in the temple itself, an example of incubation, the king sees men and women moving before him with various objects in their hands or supported on their heads; an ass crouches beside one of the figures. These figures and their deeds are all interpreted by the goddess Nina in symbolic terms whereby the king is informed that the gods have commanded him to build a temple. Here the interpretation by the goddess Nina is perhaps really the work of a diviner attached to the cult of that ophidian deity. At any rate, in this the most ancient example of oniromancy, a deity originally connected with the earth and the lower world appears as the interpreter of dreams.

Oniromancy has been persistently connected with necromancy or revelations by the apparition of the souls of the dead, who usually appear in dreams. The connection of the two ideas is essential to the conceptions of dreams as messengers of the infernal deities in whose domains also dwell the shades of men.

Ordinarily, however, visions of sleep are not direct revelations, but their significance rests upon obscure symbolism and historic conventions. For example, in Babylonia, as in Greece, the right hand was the side of good luck and the left of misfortune, since these people in taking auguries usually faced the north.1 In this way the right hand is toward the lucky east and the left hand toward the unlucky west. This principle of orientation is employed in the tablet in the University Museum to interpret certain things seen by a dreamer.

Thus lines 27-9 of this tablet read as follows.

If he gaze toward the left his adversary will overcome him.

If he look backward he will not attain his desire.”

Here we have three interpretations of actions seen in a dream all based upon the widely accepted principle of the lucky east, the unlucky west and south. The negative side of this principle appears in lines 47f.

If his left eye flow, his heart will be glad.”

Here the interpretation is made on the principle that a defect of or anything disadvantageous to the right means bad luck, and anything disadvantageous to the unlucky left means good luck.

The same principle appears in lines 60f.

If he bites his tongue at the left his heart will rejoice.”

According to this tablet the upper lip is the side of good luck and the lower lip of bad luck, that is up is propitious and down is sinister. So we have in lines 52f.

That is injury to the lucky part is of ill omen. But—

That is injury to the unlucky part points to a propitious future. Our tablet in lines 20f regards the sky as unlucky and the earth lucky.

If he look toward the earth he will be blessed.”

The principle upon which this interpretation is made may possibly revert to the ancient antagonism between the gods of light and darkness, of day and night. Since this tablet deals with dreams which were originally regarded as revelations sent by the underworld deities, for the savants of oniromancy earth would here be lucky and heaven unlucky. Perhaps, however, some other unknown principle obtained, or some ancient example of this kind may have become the norm for all future interpretation. That is, perhaps in antiquity some king in his dream saw himself looking heavenward and it turned out to be an evil omen. These specific cases if noteworthy were recorded in the books of the Babylonian diviners as in Greece. Probably a large number of the interpretations were based upon these ancient observations.

The following forecasts in the tablet are based upon simple suggestion of ideas or analogy.

If he strangle his nose, there will be his debasement.

If he flays himself, there will be his debasement.”

On the other hand, we have in the following line a possible example of a play in etymology or double meaning of words, a method so frequently and absurdly employed in the interpretation of Greek dreams. For example, according to Greek oniromancy if a man sees a pea (pisos) it is of good omen because pea signifies confidence (pistis).2 I am unaware of any etymological suggestions in Babylonian quite so absurd as this or many others employed in Greek, but interpretations of this kind do occur. Line 34 of the Museum tablet has the following: “If a man presses his nose,” the omen is good. Here the word for press (muššudu) is probably associated with a word from the same root (muššidu) which means abundance. On the other hand, this root yields a more common word (mašiddu) which means oppression, tyranny, and hence in other omens the same verb is taken to indicate an evil omen.

A good example of the principle of pure analogy in prognostication is afforded by line 23 in this tablet.

“If when he discourses he looks at the ground men will speak lies about him.” Now one associates mendacity with lack of frank behavior in speech and if the dreamer sees himself or another behaving thus in a dream the omen indicates that others will behave so toward him. In the same way whispering is associated with clandestine conduct, wherefore if the dreamer whispers he receives the following omen:

Thrusting out the tongue has been universally considered bad manners and consequently of evil omen in dreams. Line 67 interprets this act as of evil omen.

The science of the diviners, however, not infrequently incorporates prognostications and solutions of signs whose principles are completely obscure to us. According to this tablet, biting the tongue in a dream indicates that the man will acquire power and wealth. Rubbing the lips either on the right or left side is of happy omen. On the other hand, rubbing the neck (?) or back (?) indicates that he will be ill. These are probably ancient observations and facts handed down from one generation of dream interpreters to another and incorporated in the text books on oniroscopy.

The hunter’s bow being connected with conquest and the chase in real life was a prophetic symbol of good omen in the Assyrian books of dreams.

If he carries a bow and lets it fall he will obtain despoilation for himself.”

Seeing the ghost of the dead in dreams invariably indicates calamity and death for the sleeper. As in Greece, so also in Babylonia the books of divination assign specific influence to each kind of grain, herb and tree. The carrying of the fruit of the date palm indicates sorrow. If one dreams of carrying salt on his head it is of evil import. On the other hand, carrying barley in the street indicates that the dreamer will overcome his adversary. The reasons for these prognostications are entirely unknown and the mystic books contain no elucidation. However, the two following omens are self-evident:

If he carries water in the street his sins will be forgiven.”

The principle of association explains the interpretation put upon these two substances. Liquor was naturally connected with exaltation of the spirit. Water in Babylonian religion was the principal purificatory substance employed in the magic rituals of atonement. The interpretation of the vision of carrying water was, therefore, suggested by the rituals of expiation.

The tablet in the Museum is the earliest known representative of the Babylonian works on the interpretation of dreams and indicates sufficiently that the Babylonian diviners had already adopted most of the principles which we find in the more extensive but later works of the Asurbanipal Library of the British Museum. Their doctrines spread throughout western Asia and were known to the Hebrews. The story in Judges VII. 13 of the soldier of Gideon will cause every Assyriologist to recall the similar incident in the life of the soldier king of Assyria, Asurbanipal. Gideon’s depleted army encamped by night over against the multitudes of Midian. And a soldier had a dream. “A cake of barley bread tumbled into the host of Midian, and came unto a tent and smote it that it fell.” And the soldier’s companion interpreted it to mean that Gideon’s army would annihilate the foe.

Asurbanipal, in the middle of the seventh century B.C., about to advance against the Elamites, appealed to Ishtar, goddess of battle, in the night. And “a certain seer lay down and dreamed an ominous dream.” And he saw the goddess arrayed for battle with bow and quiver standing in audience with the king, saying, “Look thou up for making battle. Whither thy face is set I advance.” And the seer heard the king reply, “Where thou goest, with thee I will go, oh queen of queens.”

The Hebrew prophet Jeremiah censured the faithful of his time (first half of the sixth century) for consulting the wizards and dreamers. Nevertheless the belief in this mystic phenomenon as somehow connected with the spirit world survived into the New Testament period and has not been entirely banished from the popular beliefs of today.

S.L.

1 See FROTHINGHAM,American Journal of Archæology, 1917, p. 60. So far as Babylonian orientation is concerned his conclusion is not sustained by the tablet here described. This Nippur dream tablet gives proof of the lucky right and the unlucky left. The omens taken from births and the liver almost invariably follow the principle that a defect on the left of an organ or part of an organ means good luck, and a defect on the right means bad luck. This proves just the opposite of the generally accepted view of the lucky left and unlucky right in Babylonia. A defect on the lucky side is of evil portent, and vice versa.

2 See BOUCHÉ-LECLERCQ, Histoire de la Divination dans l’Antiquite, Vol. 1. 314.