The first number of the MUSEUM JOURNAL contained a brief notice of the fourth Eckley B. Coxe Junior Expedition to Lower Nubia. In this number I propose to give some further details of that part of the work which was carried on near Haifa, while in the next number Mr. C. L. Woolley will describe his studies of the castle and town of Karanóg, and his excavations of the twentieth dynasty tombs at Anibeh. In 1909 we selected as a promising site for exploration the place called by the ancient Egyptians Behen, which is on the west bank of the Nile about three miles south of Halfa. Almost the only visible monument of antiquity was the eighteenth dynasty temple built, as we know, by Queen Hatshepsut, which is familiar to all tourists who make the traditional excursion from Haifa to the Pulpit Rock and the Second Cataract. This temple was excavated by Captain H. G. Lyons some years ago, and a little north of it, though almost silted up with sand when we first saw it, is another temple of which first Rosellini and then Captain Lyons cleared what now proves to be only a small portion. All else was desert sand and waste with a few bricks cropping up here and there.

Image Number: 214012

In 1909 we traced the principal lines of the ancient town and found that it had been enclosed by a remarkable series of walls making a circuit of about a mile, of which area again about half was protected by strong inner fortifications. The character of these walls may be seen from Fig. 9, which shows the wall between Hatshepsut’s temple and the northern temple, uncovered by us in these two seasons for a distance of over one hundred yards.

Immediately to the north of this great inner wall is the area shown in Fig. 10. The atone pillars mark the forecourt of the northern temple; and the space in front of that from left to right is occupied by priests’ dwellings. These dwellings are raised each on the ruins of the last in four distinct levels, the highest floor being flush with the top of the pillars; so that the temple must have stood, just as ancient writers describe Egyptian temples, in a sort of pit below the surrounding houses.

Image Number: 214014

In the order of our work, however, photograph shown in Fig. 11 comes earlier than that shown in Fig. 10, for it shows the earlier stages of our digging as it appeared in February of this year after several weeks of labor. Only part of the temple is yet visible, and in the foreground the trucks are running over a level higher than the tops of the walls shown in Fig. 10. It was a long and laborious task, for the depth of sand to be shifted and run out into the river or else on to the low lying desert was never less than ten and sometimes fifteen feet. It may be useful to take the highest buttress seen in Fig. 9 as a scale. This buttress is shown more in detail in Fig. 12; it is seventeen feet high from its top to the level of its foundations. This scale then represents four very distinct historical periods. Beginning at the top there is three feet which was occupied by a building of the date of the Roman Empire (A). Next to this is three feet which corresponds to the twentieth, nineteenth and late eighteenth dynasties (B). Below this is four feet representing the early eighteenth empire (0), and below this again is seven feet which corresponds to the twelfth dynasty. Except the topmost, that of the Roman Empire, these periods are represented by distinct and well marked floors over the whole area shown in Fig. 10.

Image Number: 214013

The priests’ dwellings, which extended on the far side of the northern temple as well, yielded few antiquities, though one or two inscribed stelae and some handsome painted stone jars were found in them. But they are most interesting for the study of the domestic life. The hearths and granaries are in place, the grinding stones and the ovens, and we have left all the undecorated pottery lying exactly as its owners left it under the floors of the dwellings.

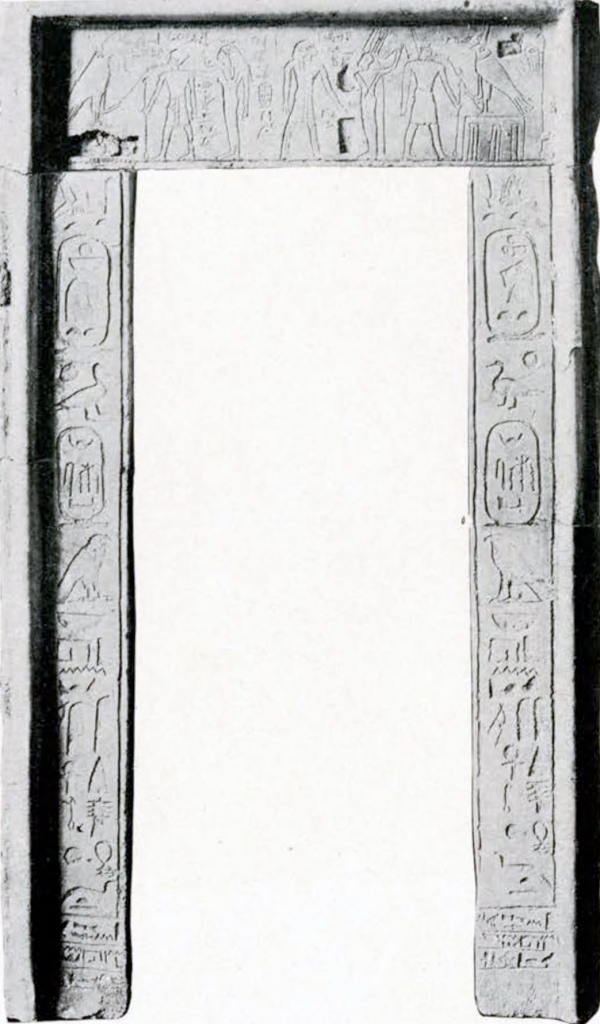

But the principal place of interest is of course the temple, of which a near view is given in Fig. 13. We found that neither Rosellini nor Lyons, though they had each the singular good fortune to find a piece of twelfth dynasty inscription, had gone below the topmost visible floor of the temple nor dug its outlying precincts. We have now cleared to its outside terminus wall and have gone down to the foundation inside and outside. The result of this has been to show that the building underwent many restorations and reconstructions. The temple in so far as it has been visible hitherto was entirely a New Empire temple, built, as we found complete evidence in inscriptions to show, by Amenhotep II. It continued in use during the nineteenth and twentieth dynasties, and the cartouche of one of the last Ramessids appears in a stela carved on the doorway. But this was not by any means the earliest temple. For in taking up piece by piece the floor of Amenhotep’s building we found face downwards used as pavement a fine inscribed doorway which is one of the chief prizes of the year and is now in the Museum (Fig. 14). It was set up by one Thuri, a notable of Behen, in honor of Aahmes, the first king of the eighteenth dynasty, a monarch whose records are extremely rare. The jambs are inscribed with the name and titles of the king and the tablet recording its setting up by Thuri; the architrave shows the king and his queen Aah-hotep worshiping before Min and before the local hawk-god Horns of lichen.

Object Numbers: E10987.1, E10987.2, E10987.3, E10987.4, E10987.5

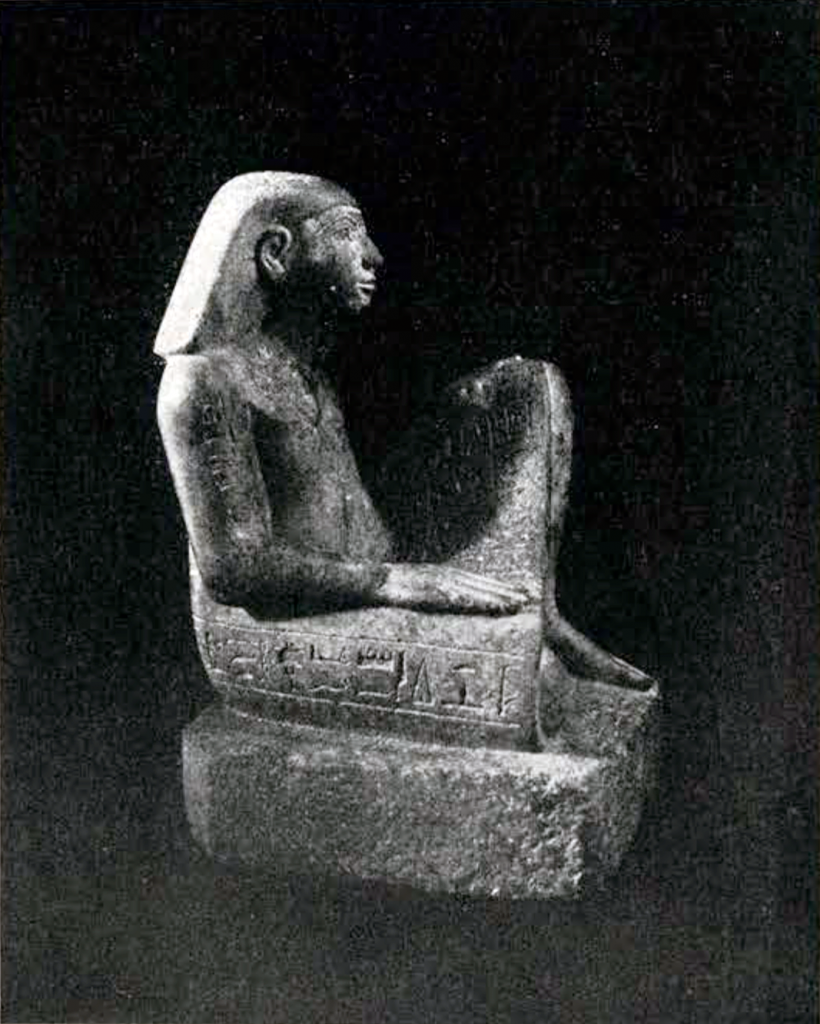

Finally even below the temple of Aahmes was a series of perfectly aligned walls running at a wholly different angle of inclination to the eighteenth dynasty temples and extending far southwards, even under and beyond the temple of Hatshepsut. Of the twelfth dynasty we found no statues this year, though it will be remembered that in 1909, when digging the cemetery of that date, we found the statuette and all the jewelry of Karynmery. This year our prizes are all of the eighteenth dynasty. At the upper eighteenth dynasty level opposite the furthest buttress shown in Fig. 9 was discovered a cache of three statuettes. Probably they had been flung out of one of the temples where they had been set up together with commemorative tablets, of which remains bearing the same names were found in digging the houses. The first is of a hard stone resembling diorite carved in fiat relief without much detail, and bears the name of Aahmes, a scribe, named no doubt after the celebrated king. This statuette was allotted, in accordance with our contract, to Khartum. The second (Fig. 15), made in a similar stone, is a remarkably fine piece of statuary of a very rare type. It represents a scribe seated in the traditional attitude of the letter writer. His name and titles are written on his kilt, on the pedestal, and on his forearm. They inform us that he was named Amenemhat, that he was a scribe, a “king’s friend” and “overseer of the king’s workmen.” The figure is unquestionably eighteenth dynasty by the style of the writing; and the place in which it was found agrees with the epigraphical evidence. Judged, however, on purely artistic grounds, it might well have been ascribed to an earlier date, and it is in every way a very remarkable specimen.

Object Number: E10980

With this seated statuette, which is now in the Museum, was found a small figure of the same person, in steatite, beautifully inscribed. In this he is represented in the conventional attitude of the eighteenth dynasty, his knees swathed in a long robe which covers the arms up to the wrists. It is expected that the Sudan Government will allow this also to come to the Museum.

The remainder of the specimens brought from this site in the present season comprise several eighteenth dynasty stelae and some very handsome painted stone jars of the same date.

Of the twentieth dynasty, from tombs at Anibeh, we have obtained some beautiful cabinet specimens which will be described in a subsequent number of the JOURNAL.

D. Randall-MacIver