When the whole destinies of a people are, as they believe, dependent upon the action, helpful or harmful, of spirits, a class of experts, skilled in means of securing the good will or combatting the malice of these spirits, comes into existence. These men—or women—are generally called, in speaking of Siberian natives, “shamans,” from the Tungus name for them.

Museum Object Number: A1588

Image Number: 2363

The shaman Langa, of the Hukachar family group of the Limpiisk Tungus, one day about fifty years ago, fired with the patriotic idea of putting out of the way as many Russians as he could, went in, so the Tungus say, from the tundra to the Yenisei, ostensibly to exchange fox and ermine pelts for supplies at the nearest trading post on the river, really to work disaster to all the white men living along the stream. Langa’s spirit helper, or one of them, was, it seems, the smallpox spirit. He sent this to the Russians—after concluding his deal in furs—and they began to die off “like sick reindeer.” After a time the smallpox spirit appears to have got beyond control and taken to killing Tungus in the tundra. So Langa, they say, sent the bird away to the north, to the Dolgan and the Samoyed.

In all the shamanist cults of Siberia, animals, and particularly birds, play a great part as spirit messengers of the shamans or medicine men, or of the gods, as the shaman’s familiars, as servants of the shamans and of the various divinities. There is no distinction made between men and animals in the matter of possession of a soul, unless it be to attribute powers to the spirits of certain animals superior to those of men. Such spirits may or may not be benevolent, and may have themselves almost the rank of gods. Among the Kamchadal of eastern Siberia, Raven was the creator. But he left the Kamchadal for the Koryak and the Chukchee. Yet the Koryak regard him not as creator, but rather as transformer or organizer of the universe. The Buryat of the Lake Baikal region believe in evil spirits which originated as the souls of wicked men, but have now the shape of malevolent birds. In this case the bird appears to be regarded as an instrument or at least a vehicle of a kind of degeneration, an analogue to which idea may be found among the Ostyak, a tribe of the northeast, who say that men’s souls go through a series of transformations after death, becoming birds, gnats, finally specks of dust.

There is a close association between the shaman and the spirits of animals. The impulse and desire in which religion is rooted is the. craving which the individual feels to get outside of himself, to loose somehow the spirit trammeled by bodily limitations that it may by contact and cooperation with other spirits, freer and hence more powerful, win strength to compel the fulfilment of desires. What can be freer than the birds? They are not bound by horizons. The shaman, watching their free flight, sees them fade through the blue, drop out of sight below the sky line. Surely they can pass to Erlik or to Ess, beyond the seventh heaven or below the ninth underworld. All a man needs for this is wings, and he sets about to secure. them vicariously by making the spirits of the birds his helpers. So he may use them for conveyance of his messages or even borrow from them the winged faculties he lacks, and surpass them in their own field. The winged powers of the Altaian shaman are thus compared with those of familiar birds. He goes to visit Erlik, god of evil, but susceptible to propitiation. On his way he crosses a yellow steppe such as no magpie can traverse; or a pale one such as no crow can pass over; and when he arrives before Erlik, the god, in amazement and anger, demands to know how he got there, for “no winged creature can fly hither.”

Museum Object Number: A1587

Image Number: 25343

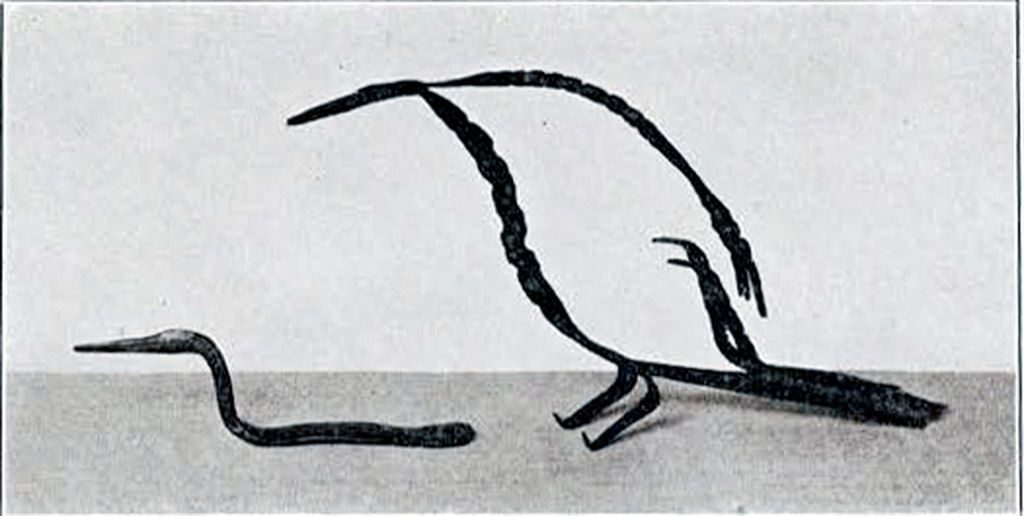

The objects illustrated here are shamanist representations of birds, brought by the Museum’s expedition to the Yenisei from the people known as Yenisei Ostyaks or Yeniseians. Their medicine men have a great reputation among all the natives of the lower Yenisei. The costume worn by the Yeniseian shaman at the present day is distinguished from the everyday dress chiefly by a deerskin apron. On this are crudely painted figures of men and women, and on the breast and below hang representations in iron of birds and other spirit helpers of the shaman. Fig. 73 shows two of these. The group on the right represents a flight of bit, divers (probably the black-throated diver, Colymbus arcticus), which are the shaman’s messengers to Khosadam, chief of evil spirits, formerly the wife of Ess, the somewhat passively benevolent chief of the spirits of good. Khosadam was cast down to earth by Ess from his seat above the seventh heaven as punishment for infidelity. She is the patron or symbol of all evil things that afflict men—cold, darkness, sterility, disease.

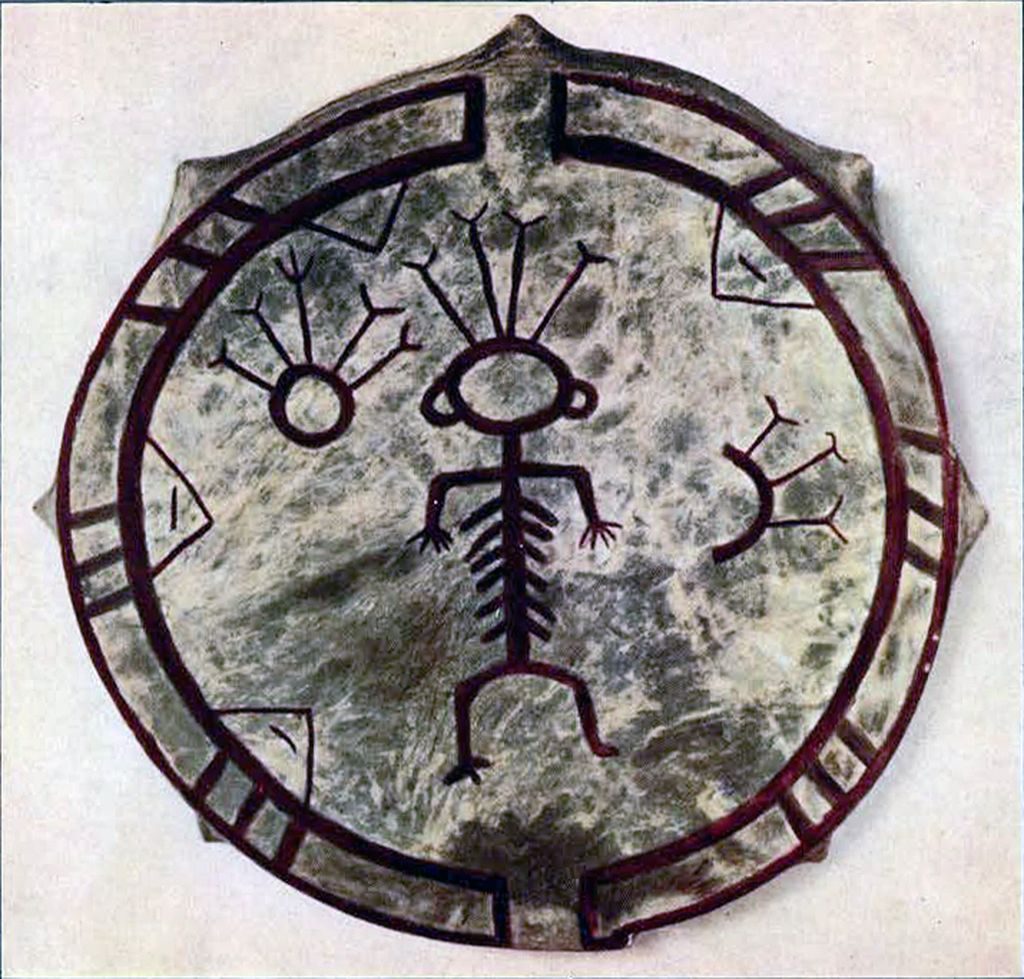

The most familiar accessory of shamanist performances is the shaman’s drum, Plate XII. In the middle of the tympanum of this Yeniseian drum is painted a representation of the shaman. The lines radiating from his head symbolize winged thoughts: with admirable economy of effort the artist merely forks the ends of the rays to suggest the wings of birds. Winged rays also proceed from the sun, to the left, and the crescent moon to the right, of the central figure. To a wooden bar which extends across the inside of the drum are usually attached small iron figures of birds: the two-headed eagle, teacher of the first shaman; the swan, sacred to Ess; and three divers, messengers to Khosadam. The smaller object in Fig. 73 is one of these swans.

H.U.H.