During the war it was a commonplace subject of conversation, and of articles in the newspapers and magazines, that for defence the soldiers of the different belligerent nations were reverting to the ages of the past. Much was said of the helmets worn by the French and Germans, and of the “tin derbies” popular with the British and American troops, as being veritable reversions to a bygone period. Experts in the history of arms and armor were called into consultation, to devise protection, by means of helmets and body armor, for the heads and bodies of storm troops. It is, therefore, worth while to study the prototypes of these defensive weapons.

Museum Object Number: MS850

In the Mediterranean Section of the Museum there has been for a long time on exhibition a collection of ancient armor from Italy. Some of it is indigenous to the soil on which it was found; some of it was imported from other parts of the ancient world. It will be profitable to study it, and see in what respects it resembles, if at all, the armor lately worn by the different belligerent nations.

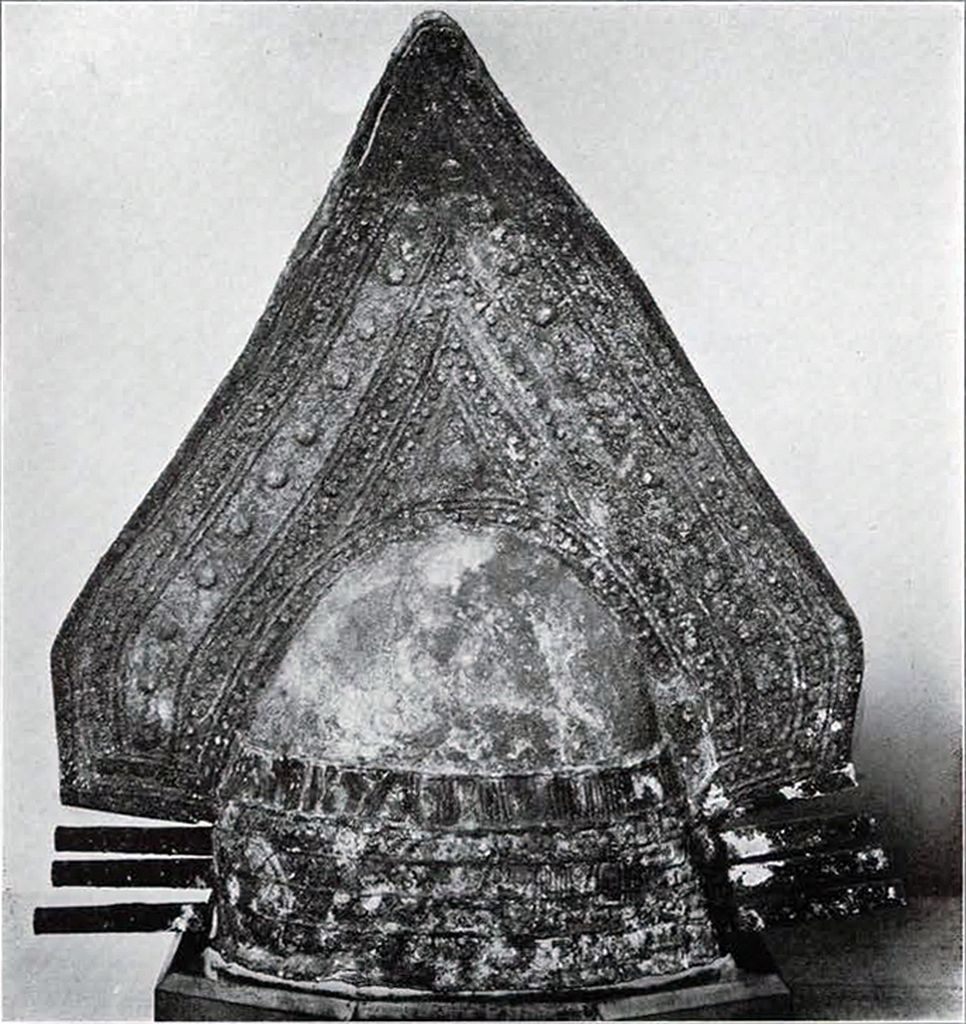

By far the most interesting object of the collection is a helmet, found in the tomb of a warrior, that was excavated for the Museum at Narce in Etruria, in 1896 (Fig. 43). The fact that helmets like this have been found in deposits of the so-called “Villanuova” period, which is Italic, and pre-Etruscan, and that their provenance is not confined to Etruria, marks them as of a civilization that existed in Italy at a very early date, perhaps anterior to the seventh century B.C. This is further confirmed by the pottery and other objects associated with them, which shows the primitive state of culture of the people in whose tombs they are found. It is interesting to note, speaking of pottery, that ancient clay copies of these helmets have been discovered, which were apparently used as covers for cinerary urns. Examples of these covers can be seen in the Villa Giulia Museum in Rome.

In height and diameter, the helmet in the Mediterranean Section towers above all previously known specimens. It is also far more elaborately ornamented than any example previously published. The crest is richly adorned on both sides with rows of dots and knobs of various sizes, which come together at the top, leaving a triangle at the center of the crest, just at the apex of the crown. This triangle encloses a large circular boss, tangent to its three sides.

Museum Object Number: MS1608

Image Number: 3602

The crown of the helmet was no less richly decorated, with rows of bosses, and incised decoration. On each side, below the crest, are three long, heavy bronze rivets, which served the double purpose of clamping together the two sheets of bronze from which the helmet was made, and of attaching the crest. It was worn “fore and aft,” with the rivets at front and back respectively.

Other objects found in the tomb with the helmet are a can teen of coarse pottery, with a groove around its edge, into which fitted the strap by which it was carried over the shoulder; several bronze razors, and fibulae, or brooches, and a large collection of ornaments for the harness of horses, as well as a fine pair of bronze bits, similar to those we use today. Assuming that these objects were used by the warrior, and are not merely votive offerings, let us see if we can deduce anything as to his physique and general characteristics. He was probably a man of good stature, with a large head, and probably wore his hair long, and in thick ringlets or waves. This is shown by the size of the helmet, which would be large for most men today, but which would not be so large if we imagine it resting on a head of thick, long hair. Then, too, the helmet was doubtless lined or padded, for the comfort of the wearer. I imagine him to be a man of a good height, by reason of the height of the crest of the helmet. No short man could wear becomingly or convincingly a helmet with such a high crest. That he was a man of action, and lived solely for war, is proved by the class of objects found in his tomb, all of which are of warlike significance. Like many primitive peoples, he was intensely superstitious; this is shown by the presence of a “bulb,” or case for amulets, which he wore around his neck to avert the evil eye. The elaborate decoration of the helmet hints that we are dealing with no common warrior, but a tribal chieftain, and a man of some importance.

Museum Object Number: MS1534

Image Number: 3599

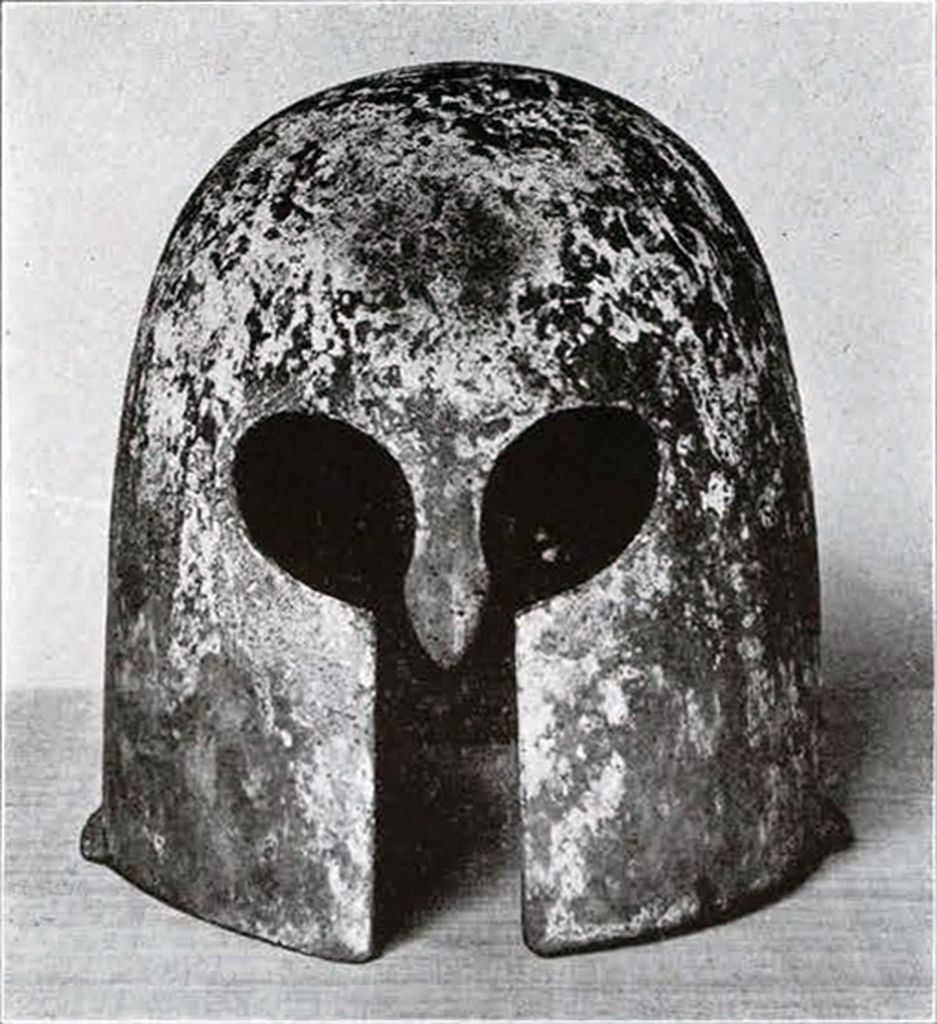

The next helmet to be described is of the type usually called “Corinthian,” as it is first represented on vase paintings of the Corinthian style (Fig. 44). The provenance of this specimen is unknown, but it was acquired in Italy. If its original finding place was also Italy, it was probably a Greek importation, or made in one of the colonies of Magna Graecia. It is the earlier type of Corinthian helmet, dating in the end of the seventh or beginning of the sixth century B.C., and has a straight back and sides. The fact that it is of equal thickness throughout, and that the bronze is nowhere reinforced, is also an early sign.

It is especially to be noted that no provision is made on this specimen for applying a crest. It has been suggested that, while on vase paintings and elsewhere these helmets are usually depicted with crests, such crests were not worn as a matter of practice, as they added weight to a piece of armor already very heavy and cumbrous in itself, and made more so by reason of the thick lining or padding, which it was necessary to wear under the bronze.

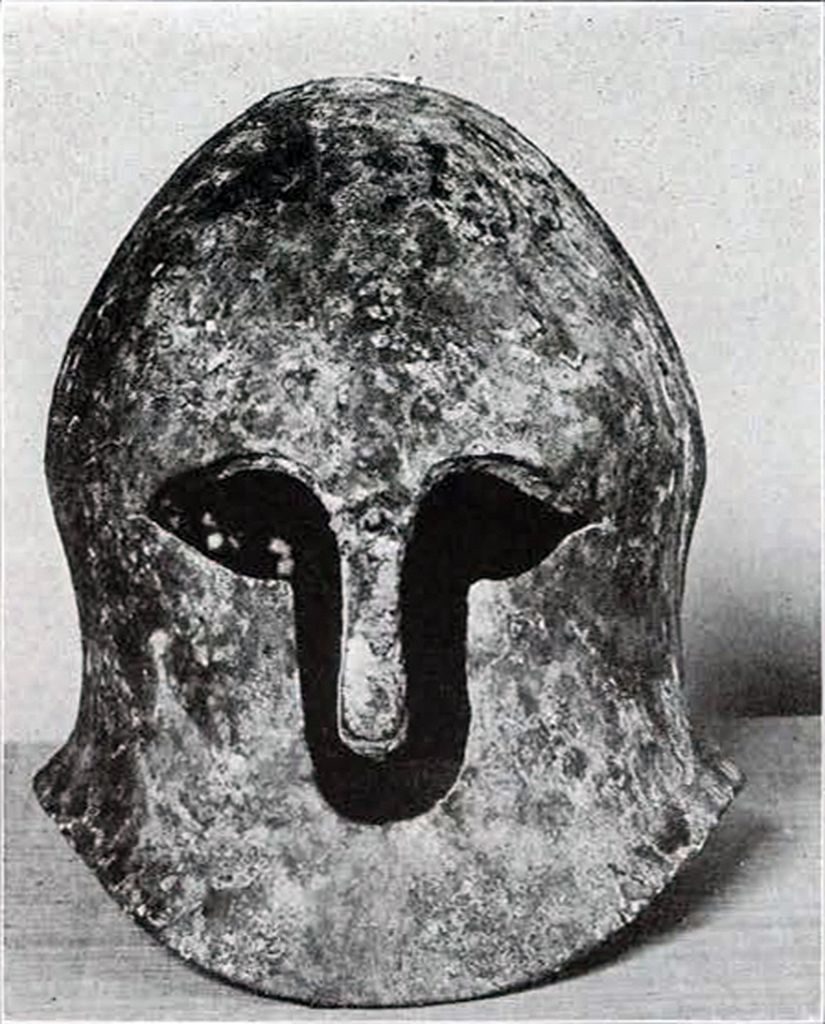

A later “Corinthian” helmet in the collection came from an excavation conducted in 1896 near the modern town of Ascoli Piceno in Italy, the ancient Asculum, which was the capital of the district of Picenum, and was not subdued by Rome till 268 B.C. (Figs. 45, 46). In the local museum are a large number of objects from prehistoric tombs, excavated in the district, which are very similar to the objects associated with this helmet, which were brought to Philadelphia at the same time. When found, the helmet was in a very poor state of preservation, and many repairs and restorations were necessary; the nose piece, for instance, is of iron, and from another specimen. The helmet belongs at about the middle of the sixth century B.C. Here we have the back shaped to fit the neck and head, and, in front, the cheek pieces sunk in, to conform with the general outline of the face. A generous space is left in the crown to provide for the heavy padded lining, worn, not only for comfort, but to increase the resisting power of the helmet against a blow. But, owing to the shaping of the helmet, padding was probably necessary nowhere else, except at the neck, and at the bottom, where it joined to a breastplate. In later specimens, as, for instance, the splendid example, No. 1530, in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the bronze is heavily reinforced in the cheek pieces and nose piece, where it is, therefore, much thicker than in. the rest of the helmet. This is a late sign, and is not found on the helmet from Ascoli. This helmet was originally provided with a crest, and on the back is a hook, which kept the crest in place, while its principal fastening was to a specially reinforced strip that was placed at the apex.

Museum Object Number: MS1534

Image Number: 3599

From the large number of objects found in the tomb with the helmet, and from the fact that the helmet itself is of a type not indigenous to the region, and was an importation either from the Greek colonies in Southern Italy, or from Greece itself, it follows that its owner was a man of considerable importance; either a chieftain, or a man who had made for himself, either in war or trade, a good standing in his community.

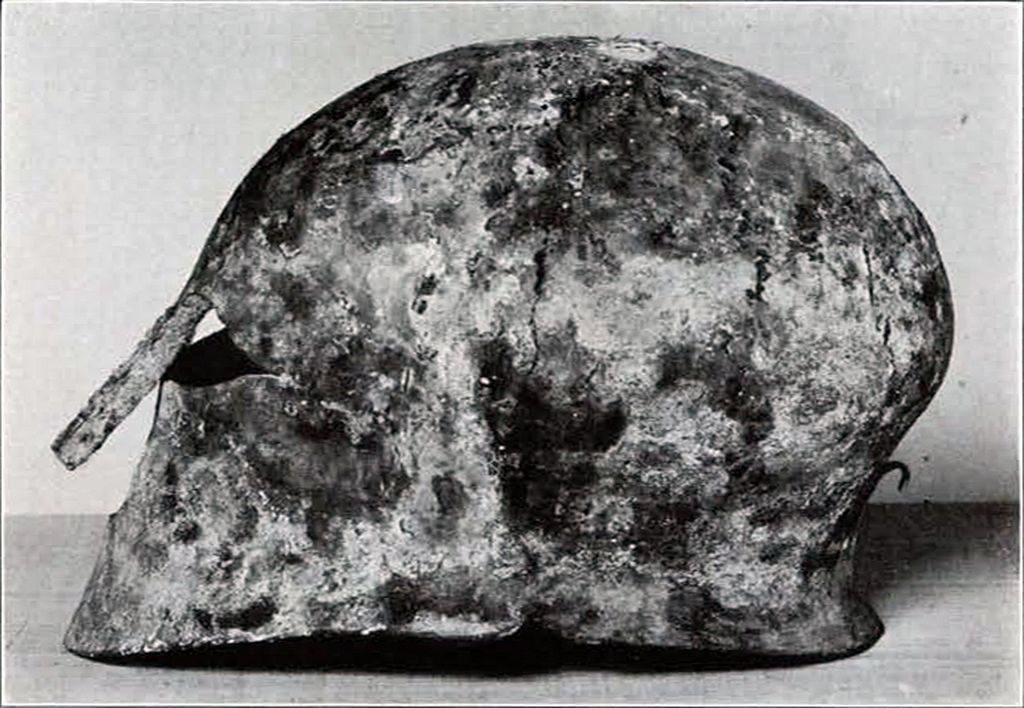

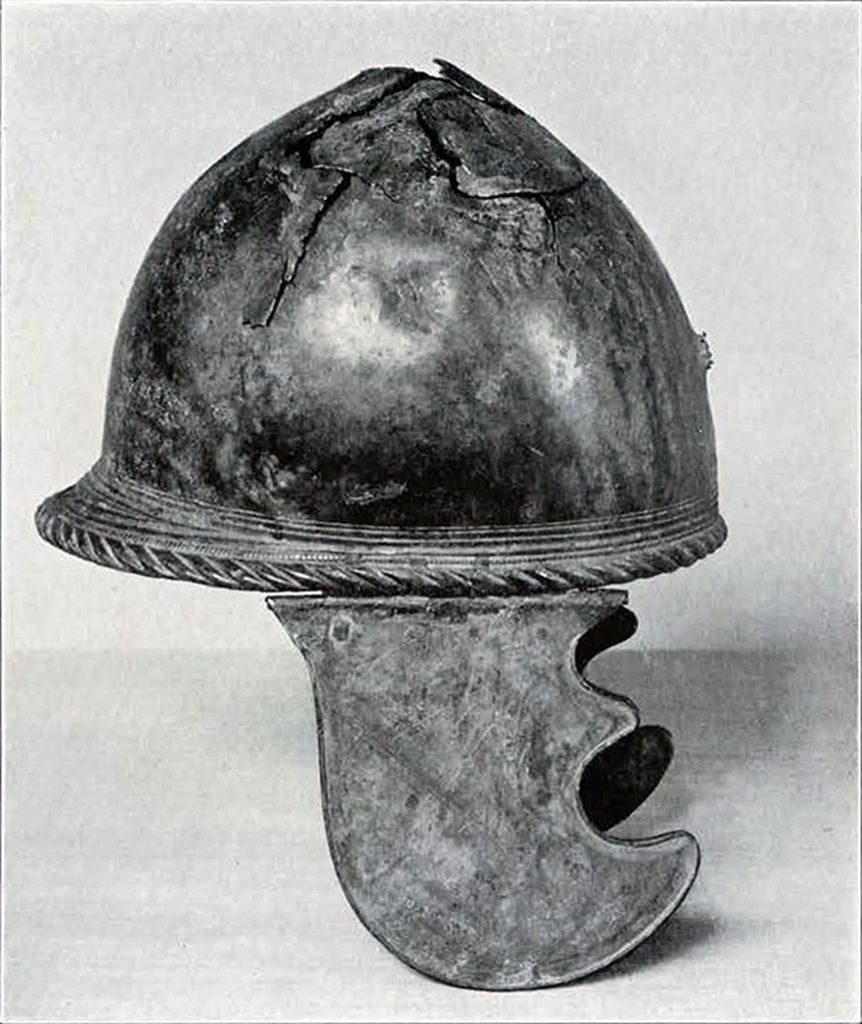

The next helmet is of a type popularly known to students today as a “jockey-cap” (Fig. 47). It is of Italic, and probably Etruscan origin, and helmets like it are very common in Italian and Gallic tombs of the fourth and third centuries before Christ, the Gauls having probably adopted this form of helmet from the Etruscans. The apex originally ended in a knob; but the helmet is now shattered by a heavy blow, which may have come from a mace, or from a rock hurled by a ballista, and which must have resulted in the death of the wearer.

Museum Object Number: MS1606

Image Number: 3600

Around the narrow brim, and the short peak at the back, runs a plait or rope pattern, with a crude knot device in the center of the front, while the base of the helmet is ornamented with a rough linear and herring bone decoration. At the sides are hinged cheek pieces, one of which is a modern restoration. The provenance of the helmet is unknown.

The small bronze statuette numbered 128, in the east room of the Mediterranean Section, in Case XXV, is of Etruscan workmanship, and shows a warrior wearing a helmet of the “jockey cap” type.

The next two helmets are of a different class, and are of a type which had a long period of development. Specimens have been found in tombs of as early a period as the seventh and sixth centuries B.C., and extend down to the end of the third century B.C. They are apparently purely Italian in origin, and have been found on the battlefield of Cannae (216 B.C.), showing they were the headgear of the Roman army, at the time of the Second Punic War. They are not found in Greece.

The earlier of the two (Fig. 48) is undecorated, save for indifferent representations of the head of a lion and a horse, sticking out from the crown, at front and back, respectively. A ridge runs along the center of the crown from front to back, but otherwise there is no decoration.

It is impossible to date this specimen exactly, as its finding place is unknown, and it is not a member of any tomb group, so that we have no contemporary objects found with it, by which its date might be ascertained. It is, however, reasonably safe to say that it antedates the other specimen, which is late in the evolution of this type.

Museum Object Number: MS1609

Image Number: 3601

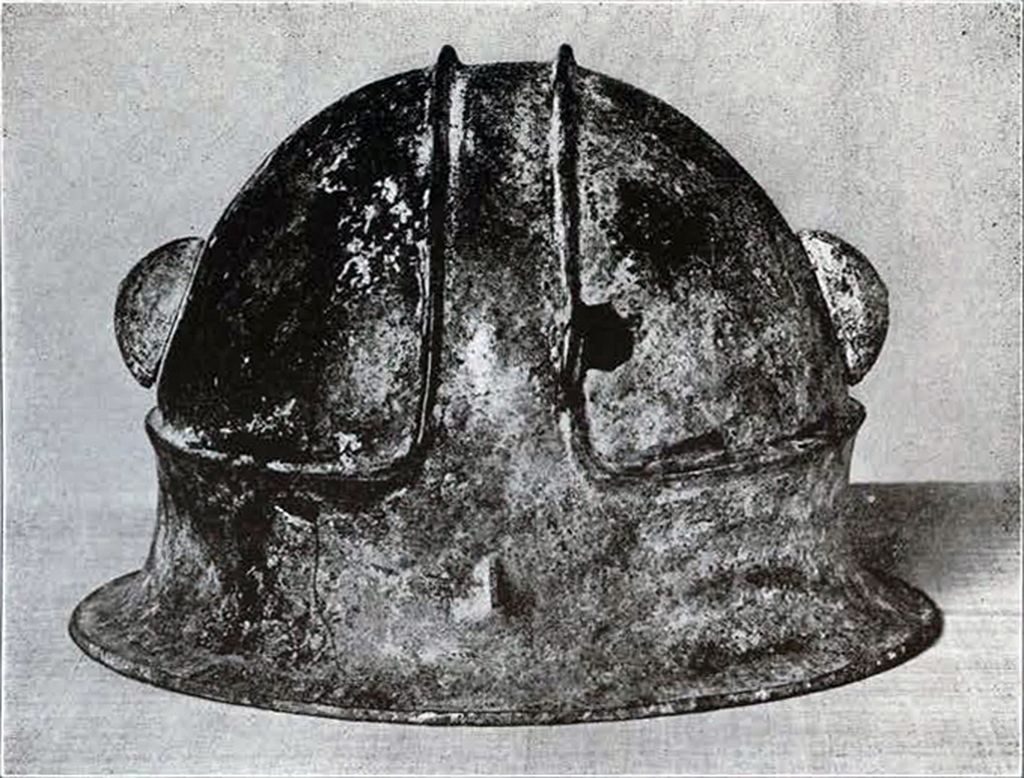

The second helmet (Fig. 49) corresponds very closely with a fine example in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, No. 1558, which is assigned to the third century B.C. On each side is a large hemispherical boss, the purpose of which was to stop a glancing blow on the head, or to deflect a blow from above. The helmet was fitted with a crest, which ran along the top of the crown, in the broad groove shown in the illustration. This crest was further fastened in position by attachment to two little tongues, jutting out from the helmet, one at the front and one at the back, each pierced with a hole, through which ran a cord or thong that tied the crest into place. This crest was probably very low and stiff, and was of service, not only as a decoration, but for turning a blow.

It will be noticed that the helmets are very different from those developed by modern warfare; but the principle involved is the same; to deflect blows on the head in the most efficient manner possible. The last two helmets to be described, bear, in point of fact, some resemblance to those worn by the French “poilus”: while the German casques, the ancestry of which is purely medieval, have, nevertheless, a neck protection something like that found on the “Corinthian” helmets. It is not a wild speculation to suppose that, in a future war, when nations may seek more efficient protection for their men against modern weapons, these ancient helmets may offer valuable suggestions to military men and inventors, for the preservation of life.

S.B.L.

Museum Object Number: MS1607

Image Number: 3603