The mission of any great museum includes among many activities two that are related to my present purpose. First to adequately and fittingly house the treasures in its keeping and second to give out in every possible way, the message that may exist in any of its possessions whatever their nature or kind. The University Museum recognizes both of these principles and is prepared to do its duty in the second part as well as in the first. If its present policy is carried out it should become distinguished in its service to the community at large, to the students who come to study within its walls and to the specialist who may need the specific help of curator or docent.

Museum Object Number: C150

It is of the second mentioned unit in this group, the student, that I wish to speak. He is, perhaps the most vital factor in the giving out of the message content of the museum, for he is the future artist, architect or designer as the case may be. As such, he becomes, through the medium of his own creation, a most potent disseminator of the wealth of information the museum holds. In his work he transmits the impressions of his museum contacts and the knowledge he has gained therefrom. This work in due time passes into the hands of the manufacturer, who in his turn reproduces the design in the form of his particular product and this rug, textile or ceramic, whatever it may be, eventually reaches the buying public. Thus in this practical result we have a concrete example of museum influence, which reaches a large and consequential audience. The responsibility is however great at any stage of the way in this distribution of worthwhile design, first that of the museum to the designer, then of the designer to the manufacturer and finally of the latter to the public at large. In the last analysis the manufacturer becomes the arbiter and it is distinctly his mission to choose wisely and with constructive judgment as to the designs he is to give out to the world, embodied in his product. Let it be said that this is precisely what our great manufacturers are doing, with the result that in many lines of textile manufacture the modern product equals the finest produced in any age and in some instances is said to exceed all previous effort. This is but a reflex of this wisdom on the part of the manufacturers to send their skilled designers and technicians to the museums to study the finest work of all ages in their particular line. This designer is our student in advanced guise, who is already familiar with the treasures the museum offers for his study and who has found out that his own imagination and technical knowledge take fire more rapidly when kindled by museum opportunities. The European designers knowing perhaps more certainly than we, that all art is related with that which has preceded it, have never hesitated to make full use of their great museum collections. Each age and time has laid its particular stone upon the foundation we know as beauty and each stone has had its value in the structure; absurd it is to try to sweep aside this slow-builded creation, to dismiss from consideration this binding together of all artistic endeavor, to return to a simple condition where civilization has not entered and left its mark, and yet there have been many recent attempts to do so. These are responsible for the “bad” art (if such a term is not a contradiction in itself) which from time to time has descended upon us. Such departures will not be made when such a cultural campaign as is now being waged by museum, designer and manufacturer, reaches the full climax of its capacity. No one really yearns to live in the midst of monstrosities, but many will involuntarily do so if they are not properly guided in the matter of selection, and this is automatically controlled if the manufacturer presents a really fine group of textiles, furniture or ceramics to choose from, so that no really bad choice is possible. Co-operation at every stage of the process must inevitably bring about this desired result.

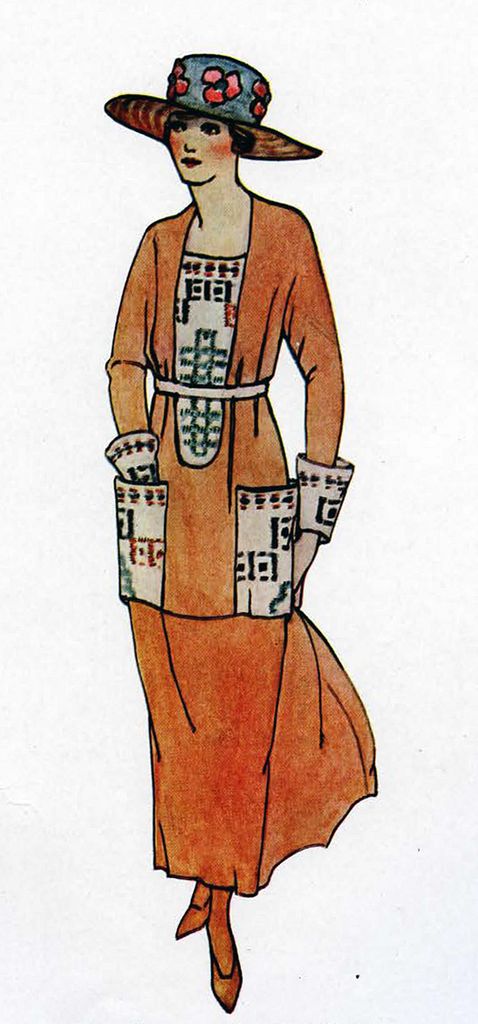

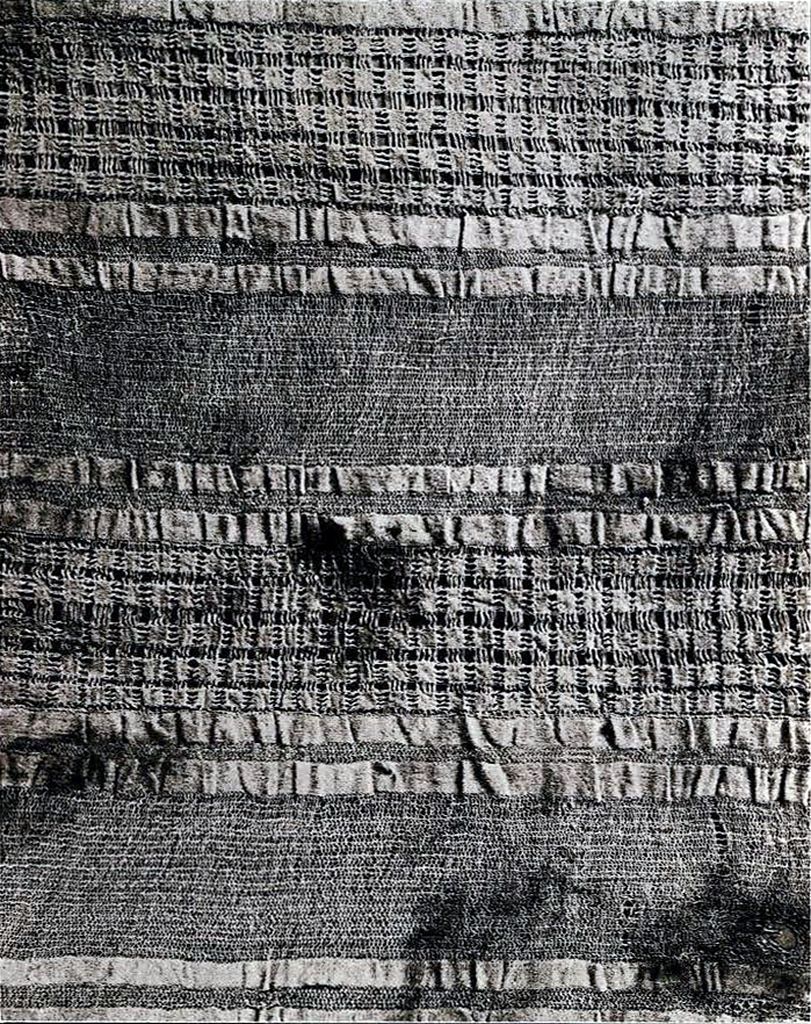

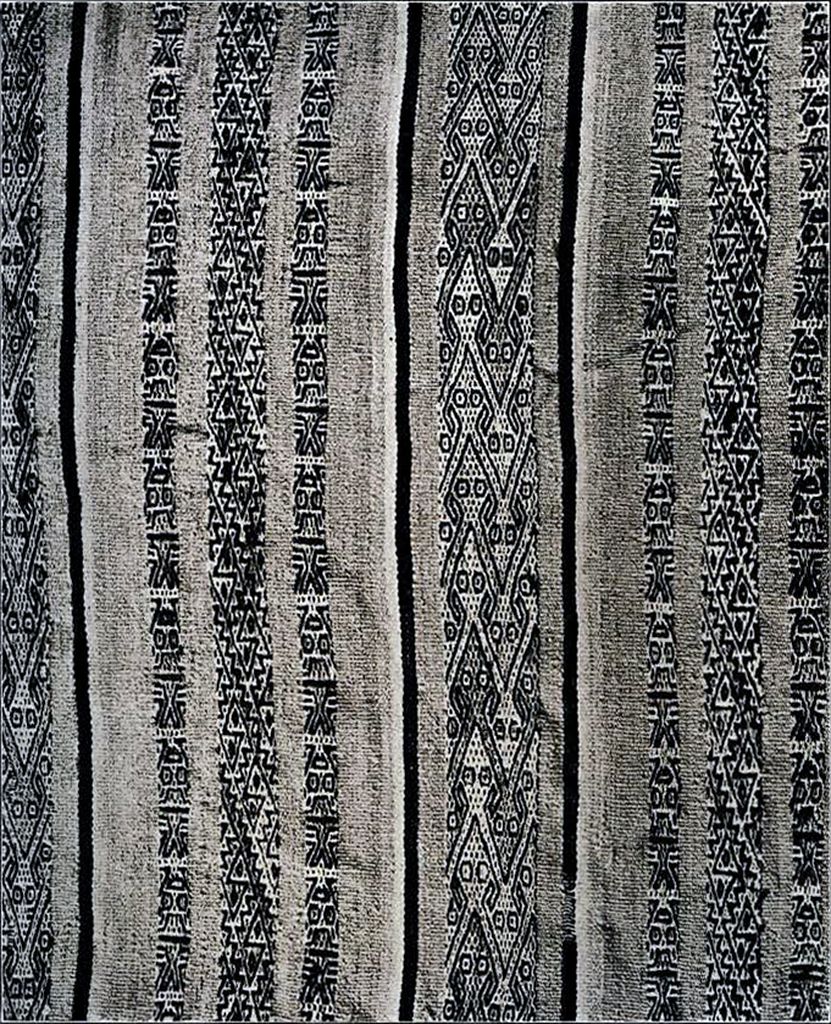

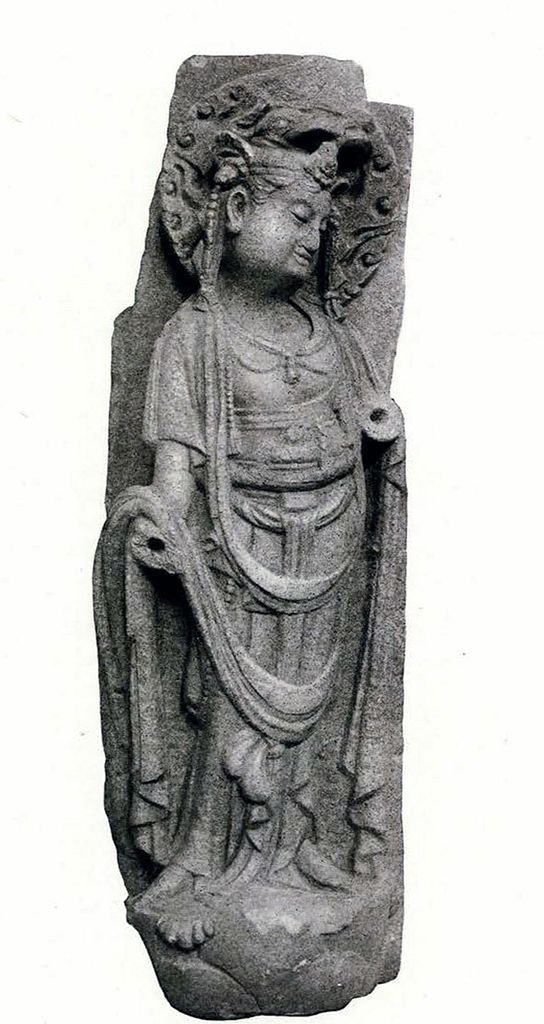

A particular instance may be cited in a group of young girls, all students of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women in the class of Costume Design and Illustration, and their unique work done at the University Museum last year. This group will be interesting because the nature of their work may seem entirely removed from the museum. These students came to the Museum with a definite problem; their instructor had told them to design a gown, the inspiration for color and line for the garment to be obtained from something in the Museum’s varied collections. They were told to explore the place and with its customary interest, the Museum placed every resource at hand. Though this was the first experience of the class, but one often repeated, the results in many instances were charming and their inspiration in several cases was drawn from sources supposedly requiring sophisticated appreciation. It is highly gratifying to a teacher when a first-year student produces as credtiable a design as that of Miss Bux (Plate X), who found in the Chinese stone statue of a Bodhisattva, lines that were admirably suited to the design of a tea-gown and who adapted the same for her design, using as a color scheme the color notes found in a particularly lovely bit of Roman glass. Miss Binder found a similar source of inspiration as will be seen in the reproduction of her design, shown in Plate XI. At later visits, Greek vases furnished ideas both in line and color for smocks and tunics, and Chinese porcelains and enamels gave, rich suggestion for color scheme and ornament for many a gown. A great source of delight and a veritable mine of suggestions was found in the group of Peruvian textiles in which the Museum is particularly rich. A design by Miss Ashton (Plate XIII), is here reproduced to show what an agreeable use is made of color and applied design as derived from one of the Coptic textiles. The Coptic textiles proved to be a source of pleasure to many of the girls who were interested in creating designs that involved the use of embroidery. A fashionable filet crochet sweater was derived from the pattern and weave of one Peruvian textile and the Museum, and all museums, became a new thing to many of the girls, because of this simple investigation which showed how the arts and crafts of yesterday might be linked with the dress and occupations of to-day.

Museum Object Number: C98

It would have been perfectly possible to take this class and put them down in front of a group of costumes with instructions to derive their designs therefrom; this is a stereotyped method and entirely valuable at certain stages of the student’s development, but working in the more synthetic way the student contracts the habit of going about the museum with eyes and mind open to all influences instead of having a distinct bias towards an interest in one particular thing. The resulting training is of course of wider art value and education than it could possibly be otherwise. It may be interesting to note in passing that some of this same group of girls are to-day designing for leading tailors and modistes, for leaders of society whose gowns are particularly noteworthy; others are illustrating modern costume for the daily press and magazines and all are doing highly creditable work.

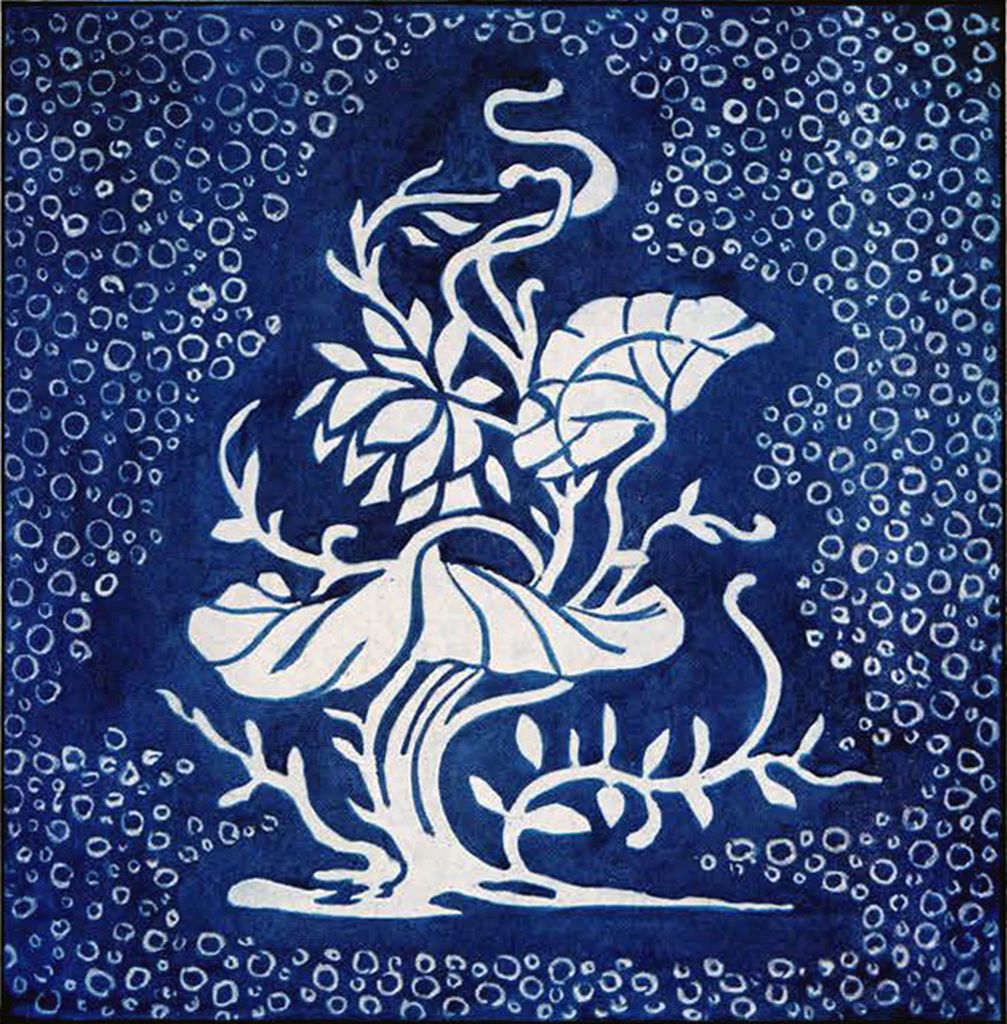

The better known class of designer, the designers of silks, wall paper, rugs, textiles for decorative purposes such as cretonnes, brocades, chintzes, lace curtains, of such utilitarian products as linoleum and oil cloth, is much more in the public eye because his result is ever with us in its many guises. To him the museum offers a very fertile field as almost every piece of textile or ceramic offers a suggestion. Accompanying this article are the photographs of suggestions for designs for printed foulards, which were derived from some of the blue and white Chinese porcelains and a Ming specimen, all possessions of the Museum. It will be noted that the design is not copied precisely as seen upon the porcelain but adapted so as to better suit its use upon the surface of silk, as a piece of feminine apparel. The taste of the designer and his power of selection must always come into play in such adaptations, for he must preserve the distinctive character of the motif and at the same time make it appropriate for the new use. Often he changes the size of a motif, reduces a color value and exercises his artistic censorship generally. Intelligent selection of this sort produces a result which successfully refutes the theory that designs for textiles should always be derived from textiles, that those for ceramics should have their origin in kind and so on. One of the designs reproduced herewith (Plate XVI), includes a suggestion for a glazed chintz or a drapery silk for rather delicate use. This is almost a literal translation of the ornament upon a Rhodian plate. In the original the colors, red, blue and green, were very strong and rich while in the design for the chintz they appear very much attenuated and the motif itself appears reduced in size to better suit the new purpose of the design. This same Rhodian ware offers to manufacturers of household china, a stimulating color scheme for use in breakfast sets and the floral motifs of the same, especially the Rhodian lily, lend an air of grace that is very pleasing. Other potteries, Sultanabad, Rakka and Rhages ware offer the most beautiful ideas for color as well as ornament which would be applicable in a hundred ways to textiles and ceramics. There is a Chinese lacquer screen which has become a veritable Mecca for students and designers because of its seemingly inexhaustible fund of suggestion. It is also very interesting to think that the rich color of a band of porcupine quill embroidery may one day appear in the design of a silken ribbon quite as beautiful in pattern and color as an oriental fabric, but wholly indigenous to the continent of North America. The designs of the North American Indian, in his various locations and varied craft, are studied by the student of design for their abstract quality, and the simplicity and beauty of the shape and designs of the Conebo pottery of South America also furnish much inspiration. The list could go on indefinitely with a thousand variations, for the Museum has many treasures, each giving out a special message. It is the desire of the Museum that these messages shall reach their special sphere of influence. No timid student need hesitate to ask for information or help for there is at his service a docent whose message it is to explain away his perplexities and to set before him the resources of the Museum’s collections. The Museum is in no way more truly at the service of the public than in this constructive work of guiding and aiding the student, designer, or craftsman who comes to the Museum for help. He most certainly finds that which he seeks and as a consequence, in his work endows us with a translation of the beauty that once was Egypt’s, let us say, and gives us in terms strictly modern and his own, our place in the great history of art production. He thereby makes our modern design a link between that of the ages which are passed and the future which is to come.

L.H.