I

THE great stela of King Ur-Nammu has been called by Mr. C. Leonard Woolley in his successive reports of the work done by the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania to Mesopotamia, the most important monument yet found at Ur, a magnificent example of the art of the time, a historical document whose appeal is not less direct, ranking despite its fragmentary condition with the stela of the Vultures in the Louvre, as one of the two most important relics of Sumerian art known. Why not call it the Stela of the Flying Angels?

Museum Object Number: B16676.1A

Image Number: 8427, 8878

Museum Object Number: B16676.1A

Image Number: 142807, 8429

On this stone were recorded the achievements of King Ur-Nammu, the founder of the third dynasty of Ur about B.C. 2300 and builder of the great Ziggurat as well as the constructor of many canals. Ur-Nammu’s reign was short. Whether the stone was erected by him or by King Dungi, his son and successor, is an open question. King Nabonidus of Babylon, who repaired and finished the Ziggurat of Ur, states that it was founded and partly built by Ur-Nammu and Dungi, but never finished.

The display of the main fragments of the stela in the Ur room at the Museum gives a fine opportunity for a closer study of its historical and symbolic scenes. These notes will supplement the information published in the first report in the MUSEUM JOURNAL of March, 1925.

The stela is a limestone slab, 1.52 m. across, at least 3.00 m. high —if all the fragments were in their proper places—slightly tapering upwards with a thickness varying from 0.28 m. or more to 0.24 m. The top was rounded as in the stela of the Vultures and the Berlin stela of Gudea. A portion of the original curve is still preserved on the fragment of the flying angels. The stone was carved on both sides with scenes in relief. There were probably five registers, each 0.41 m. high, on the face, and as many on the back. An exception must be made for the top registers below the curve, which were double size or 0.82 m. high. Raised borders, 0.055 m. high, separated the registers. A border of exceptional size-0.22 m.—was reserved for a two column inscription.

II

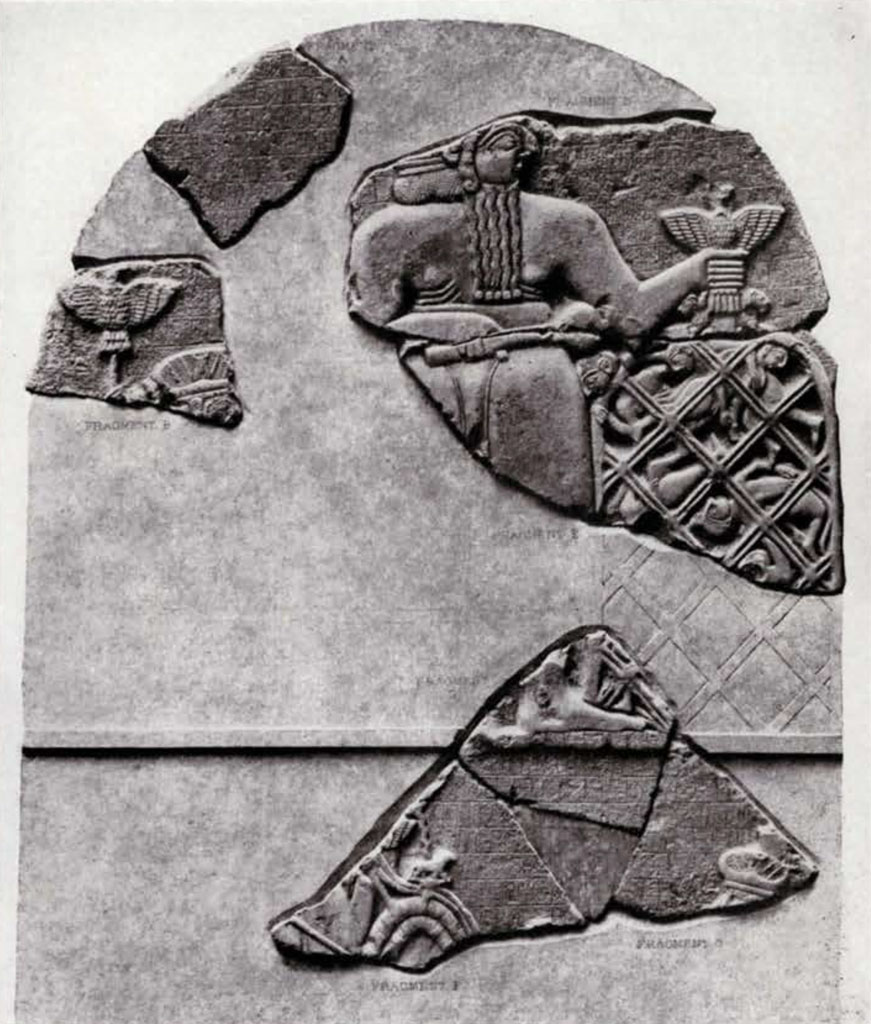

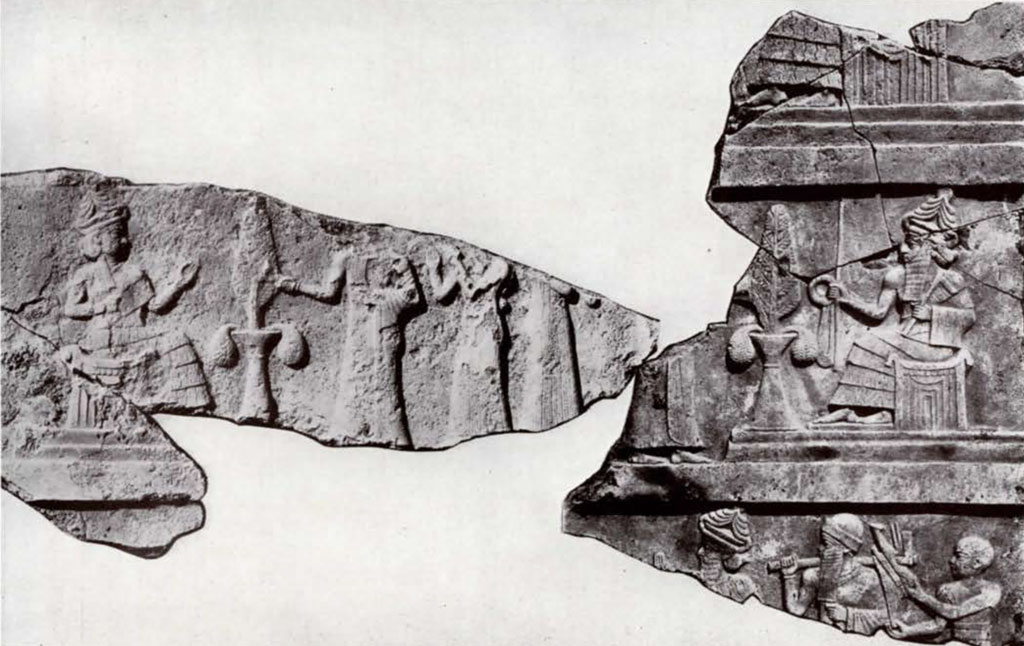

Top Registers. Scene of the Flying Angels. The Heavenly Gift of Water

Graceful girlish figures glide downwards from heaven holding with both hands the overflowing bottle, whose precious liquid brings life and fertility to green palms planted between the enthroned Moon god and the standing worshiping king of Ur. Messengers from heaven, they wear the horned mitre, their long dishevelled hair is floating on their shoulders. They are a prototype of the Greek Nike, and not unlike the Botticelli angels. Their plaited linen robe, passing over the left shoulder after the Sumerian fashion, leaves bare the right breast showing its youthful curves below the outstretched arms. One hand is clasped around the neck of the bottle, the other hand supports the round bottom.1 The motive of the overflowing bottle is not new, it had been for over a century the delight of the stone carvers at Lagash, a city forty miles north of Ur. These men loved to represent a network of those overflowing vases connected by their liquid streams, or a chain of young nymphs passing from hand to hand the same spouting vase. Sometimes a green bough is planted in its mouth, or little fishes swim along the streams. Minor female deities or the bearded Gilgamesh hold the vase preciously against their breast. Finally, the spouting vase is placed in the hands of the enthroned god on the very seal of Gudea, the local ruler. The same scene is repeated on the larger Gudea stela in Berlin. On both monuments the water escaping the hands of the god falls in wavylines at his feet. This is a precious indication for a reconstruction of the much damaged stela of Ur-Nammu. Enough is left of the liquid stream bathing the foot of the enthroned god (upper relief on page 84) to connect it with the fragment of the flying angels. A small fragment (page 82) shows the stream of water, and an extended bare right arm which may as well belong to the seated god as to one of the flying angels.

Image Number: 7912

The large mitre with four pairs of horns surmounted by a crescent belongs certainly to the enthroned god below the flying angels on the top register. The larger size of the head compared to similar mitres on other fragments would prove this. The crescent decorating it shows that the main figure, as might be expected, was that of the Moon god Nannar, the king and patron of Ur. Why the crescent is missing on the mitre of the god in the second register (pages 84 and 85) is not explained. Perhaps that god holding the rod and the line is not the Moon god himself, but another deity like Ea, the great builder. In the construction of the temple of Lagash the same god Ea is on record as having laid the foundation. It was a state affair in which every talent and expert was welcome.

The whole composition of the angels bringing rainwater from heaven is new and so far unique in Mesopotamian art. They answer the eternal question of that dry land, water from the sky or water from the river, rain or flood, the fertility of the country depending entirely on good and continuous irrigation in the days of Ur-Nammu and today. But the waters from above, and the springs of the deep abyss are all in the hands of the gods. A wise ruler will attend to canal cutting and cleaning, but who will fill them with clear running water if not the powerful Moon god when satisfied with his own people? The building of his great tower is a meritorious work that will in return bring blessings in the land. In the same manner Gudea at Lagash was rewarded for his building of the temple by an exceptional overflowing of the Tigris. The gift of water is the best introduction to the various scenes on the stela.

Image Number: 7913

The flying angels appear on both sides of the stela and seem to have been repeated at least four times in the top registers. Perhaps each angel symbolises each of the four winds at the four points of the compass, interesting the whole heaven in the welfare of the land of Ur.

The worshiping king stands in front of his god, his right hand in one instance lifted to the level of his mouth, which is the traditional gesture of adoration. He wears short hair, long plaited beard, bracelets and necklace. His simple fringed shawl covers the left shoulder and leaves bare the right arm in true Sumerian style. The flounced woolen garment of “kaunakes” is reserved to the god. A round woolen turban, in vogue since the time of Gudea, covers the head of the king. The name of King Ur-Nammu has been found engraved on a mere flake of stone which is the lower part of the king’s garment and probably belongs to the top register of the face of the stela. At least it has been reconstructed in that position on page 85. But we must not forget that the feet of the king have been restored and might as well be turned to the left as to the right and their position in front of the right hand throne is not certain. In any case the figure of the king is placed too close to the throne of the god and should stand towards the middle of the register back to back with a second figure of the same king facing left, above and in the same position as the two assistant goddesses in the second register (page 85). In fact, traces of the second figure of the king, back to back with the first one, are still visible on pages 74 and 76, despite the severe hammering of the heads at the hands of savage enemies, and there are also traces of the green palm (page 76) still visible between the streams of water pouring from heaven. The palm was probably planted in a vase between bunches of dates as in the register below. The watering of the palm is both a graceful and sacred rite and takes its full meaning in a land where dates are one of the staple foods, where palm groves yield the richest and most reliable harvest, large enough to supply export even today from Basra port to the rest of the world.

III

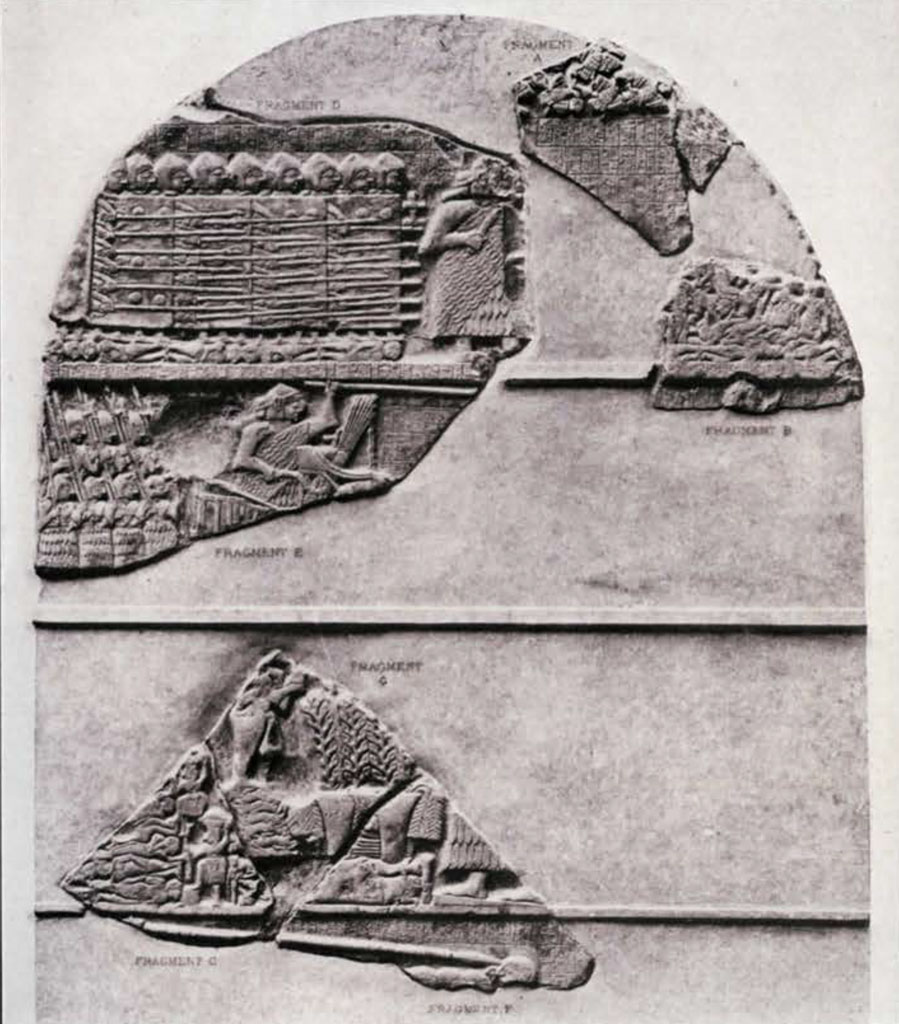

Scene of Libation to the Enthroned God and Goddess.

The Builder’s Mission(Pages 84 and 85)

This is a classical scene at Ur of the Chaldees and is borrowed from the daily ritual, in the various shrines which the progress of excavation has revealed. There was the statue of the god raised on its brick base at the end of the double room opening on the inner court. Bunches of dates and palms were placed in front of the statue in one of those hourglass shaped travertin vases, whose very fragments have been recovered in the ruins, bearing engraved the name and dedication of many rulers and kings. The king approaches the statue and pours water on the offerings from one of those conical vases, of which there are many examples in our collection. One elegant alabaster tumbler bears a cartouche with these words:

property of the moon goddess. a worshipping goddess is assisting king, with both hands lifted in sign adoration.

Dresses and headgears vary with rank and dignity. God and goddess wear the mitre with four pairs of horns, emblem of divinity, long hair tied behind in a chignon, the best flounced woolen garment covering the left shoulder, armlets probably, and necklaces, the goddess a tight dog necklace of five rows. Their feet are bare. The god is known by the long plaited beard ; the goddess, by the long locks resting on her shoulders. The right hand is extended in sign of gracious welcome, or holds, in the case of the god, the line and rod of the architect, in his left he wields a bronze adze like a scepter. This has been interpreted as the mission given by the Moon god to King Ur-Nammu to build his house and great tower. The dream of Gudea, the vision of King Solomon, and of the prophet Ezechiel are other famous examples of the builder’s mission. The interpretation is confirmed by a fragment of the third register where the king carrying on his shoulder the adze and the instruments of the mason, basket, compass, ladle and trowel, starts in solemn procession to lay the corner brick, his own patron god leading and introducing him. A servant of the temple, all shaven and shorn, helps to shoulder the king’s load.

Museum Object Numbers: B16676.37 / B16676.4

The assistant goddess in the second register wears a long linen plaited garment covering the left shoulder. The long locks of her hair hang down her back. Like the flying angel, she wore probably a mitre with a single pair of horns. Her part is subordinate and might have been played by the high priestess, generally a daughter of the king and naturally presiding at the libation rites.

The libation is poured by the king himself, who never lost his priestly right and sense of being the true representative of the god. The high priest in the temple is only his delegate discharging the duties of the daily ritual.

A comparison between pages 84 and 85 shows that the head of the king has been twice restored, also the upper part of the body of the king facing the god. This last restoration might be improved to come nearer the original. The beard is too large. The ear must be partly covered by the turban. The two shoulders must be in front face, and not in perspective. The shawl must pass below the naked right arm and over the left shoulder. The king holds the libation cone in the right hand alone, while the left is lifting the folds of the fringed shawl.

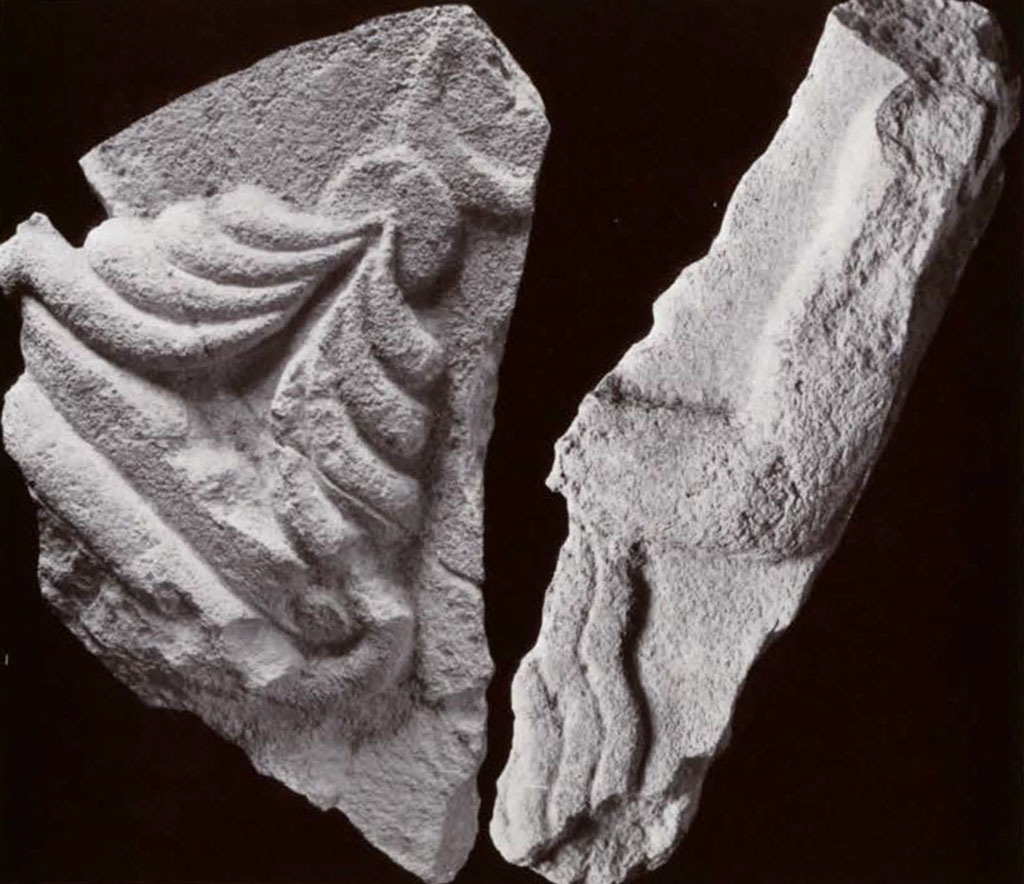

It is remarkable that a perfect join between the fragments was found across the last mentioned figure of the king, giving the original width of the stela, and not less interesting is it to learn that the fragment of the ritual sacrifice (page 87) was the back of the libation scene before the seated goddess. In fact the fragment was sawn off the block on the field, the libation scene being face down and unsus¬pected. The scene of sacrifice on the face of the block was so brittle and damaged that it had to be waxed and plastered and then sawn off to be removed safely.

Museum Object Numbers: B16676.12A / B16676.14

Image Number: 9180

IV

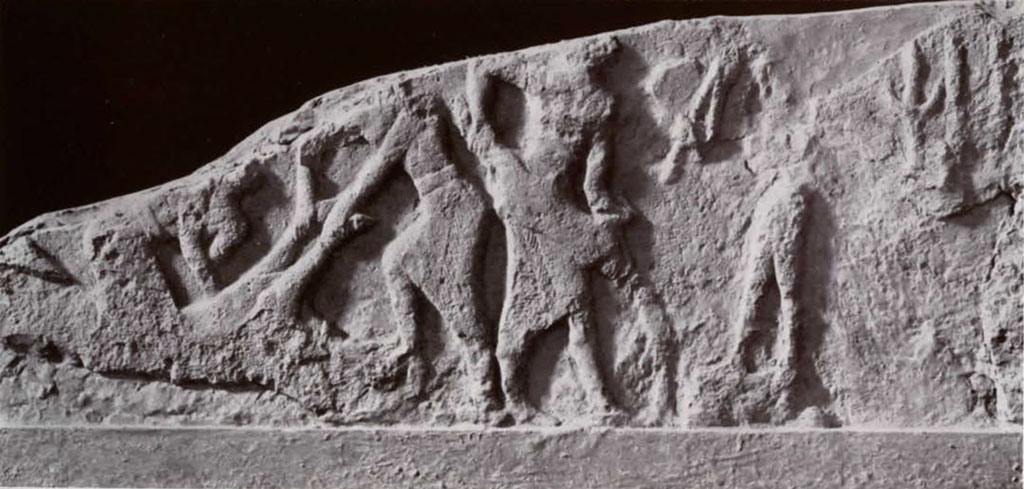

Scene of Animal Sacrifices and Divination

(Page 87)

All has been said about that remarkable sculpture. We need only to quote the words of Mr. Woolley: “That scene of sacrifice is unexampled in Sumerian art. A bull has been thrown to the ground and lies prone. One man sets his foot upon the animal’s chin and grasps its forelegs. Another stoops over the body and cuts open the breast to examine the liver, for divination by the liver was one of the commonest forms of Babylonian magic. Meanwhile a third man has cut off the head of a he-goat and holding the body like a water skin by the hind legs and the neck pours out the blood in a stream in front of a low base whereon stands the statue of a god bearing a flail. This is the earliest known representation in art of the practice of divination and of animal sacrifices at Ur of the Chaldees long before the days of Abraham.”

The men wear only a fringed loin cloth down to the knees, with a belt girded about their body and supported by a strap over the left shoulder. They are servants of the temple, priestly butchers in their working clothes. Two knife sheaths are stuck in their belt. The prone bull must have occupied the centre of the register. Toward the right, crescents on poles at the back of the statue are probably emblems decorating the entrance of a shrine.

Museum Object Numbers: B16676.12A / B16676.14

Image Number: 8414

V

The Canal Inscription. Big Drum, Prisoners and Scenes of Sacrifice (Page 88)

The fragments of the canal inscription have led to a further reconstruction of the stela. The digging of canals is the most important of the duties of a Mesopotamian ruler. Ur-Nammu did not fail in that duty and wanted future generations to know it. The long list of his canals supports his claim to have made of the land a new Garden of Eden. He made also of Ur a head harbour where the boats of Dilmun, Magan and Meluḫḫa would unload the products of Egypt and India, gold, silver, precious wood and stones. The three fragmentary registers above and below the inscription are probably a commentary on his activities in peace and war.

In the upper register (page 90): “There is a throne on which was a seated statue, probably that of the king, and before him a man armed with a short baton who guides another man apparently a prisoner with his arms tied behind his back. This must be a commemoration of Ur-engur’s victories in war.”

The two fragmentary heads inserted on page 90 show a new type of servant no longer shaven and shorn but wearing short curly hair and beard. This is probably a class of workers—musicians, farmers—not so intimately connected with temple ritual activities.

Image Number: 8426

In the lower register (page 91) two men beat an enormous drum and may well be celebrating the triumph of the king. Metal pieces round the drum add to the effect of the beating done with the flat of the hand if we trust similar reliefs found in Lagash. The drummers wear the short curly hair and beard described above. Their long plaited shawl is not thrown over the left shoulder but attached to the waist over the loin cloth, showing their bare legs in front through the natural opening. The upper body is stripped for the vigorous action of drum beating. A third musician behind the right drummer keeps time by clapping his hands.

The last register below the inscription (page 92) contains another scene of sacrifice. “The king, behind whom stands an attendant priest, faces a simple altar or base on the other side of which is a man ready to pour a libation from a slender vase.”

The king between the libator and the worshiping priest has a passive attitude with both hands clasped or pressing to his breast some defaced object. His higher stature may be a conventional expression of his greater dignity. We may conjecture that the figure represents a statue of the king placed on record in the temple and later worshiped as a god. The statues of Gudea were in their turn an object of cult and Ur-Nammu’s son, Dungi and his successors, were in their lifetime honoured like gods and had shrines to their name. If the stone has been erected by Dungi as a memorial of his father, nothing could be more natural than this scene of worship and its position at the lower part of the back of the stela is very modest and proper.

The fragment restoring the head of the libator, and a few signs of the inscription, shows also one of those palms planted with bunches of dates in a slender vase, which never fail in scenes of libation.

Museum Object Numbers: B16676.28A / B16676.28B

VI

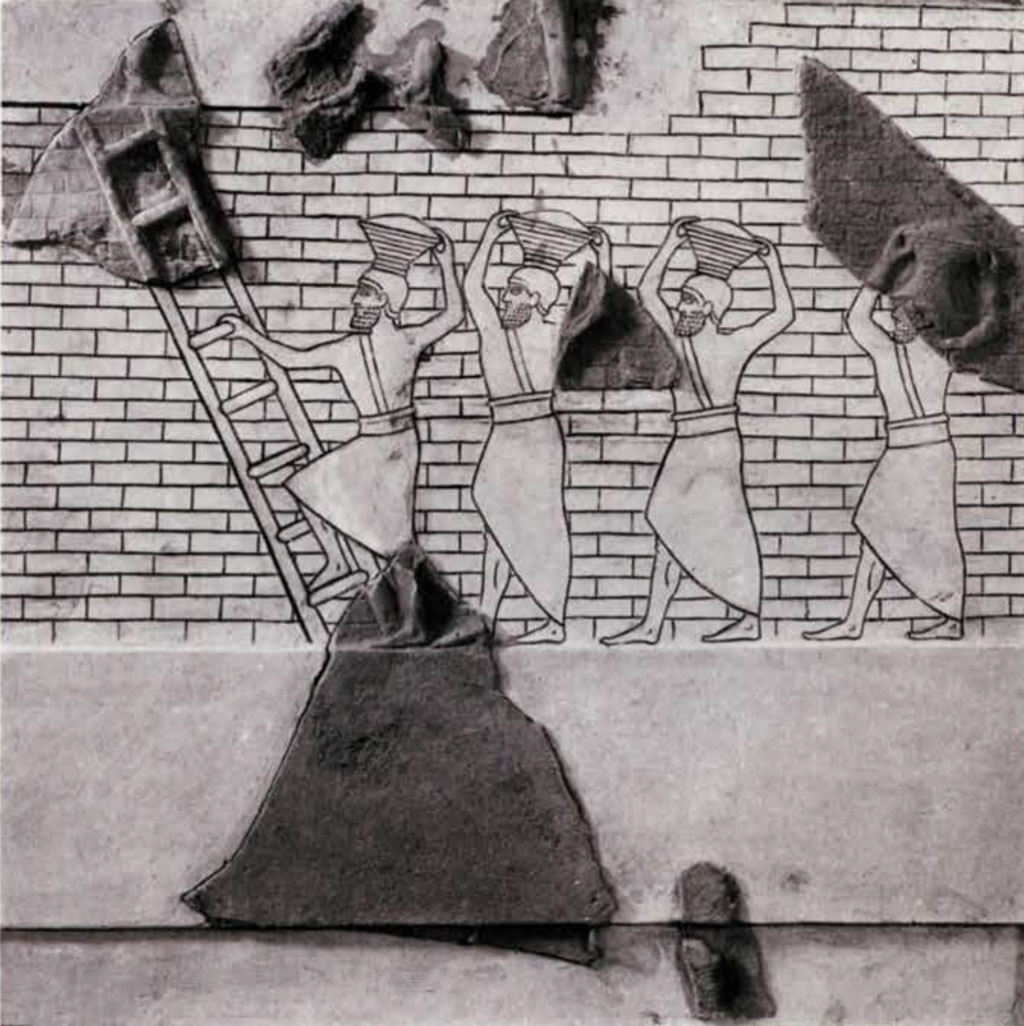

The Building of the Ziggurat

(Page 94)

An attempt has been made to restore that interesting scene which is one of the main reasons for the carving and erection of the stela, the actual building of the stage tower with bricklayers at work and labourers climbing ladders with baskets of mortar. They wear the same short hair and beard as the musicians and farmers. Their loin cloth and belt have been copied on the figures of the butchers. The belt is not certain and the strap ought to pass over the left shoulder. The figures have been given a height of 0.30 m. from the ground line. The whole composition evidently was more than 0.41 m. high and may have covered two registers.

The band below the foot of the ladder is 0.21 m. high and forms an exact counterpart of the band carrying the canal inscription. There was another register below this band as below the inscription. The building of the ziggurat should be the fourth register of the face, but its connection with the third is not established.

A small bearded head has been placed for the present at the lower part of the plate, with no other reason than to fill a gap.

Image Number: 8421, 8422

VII

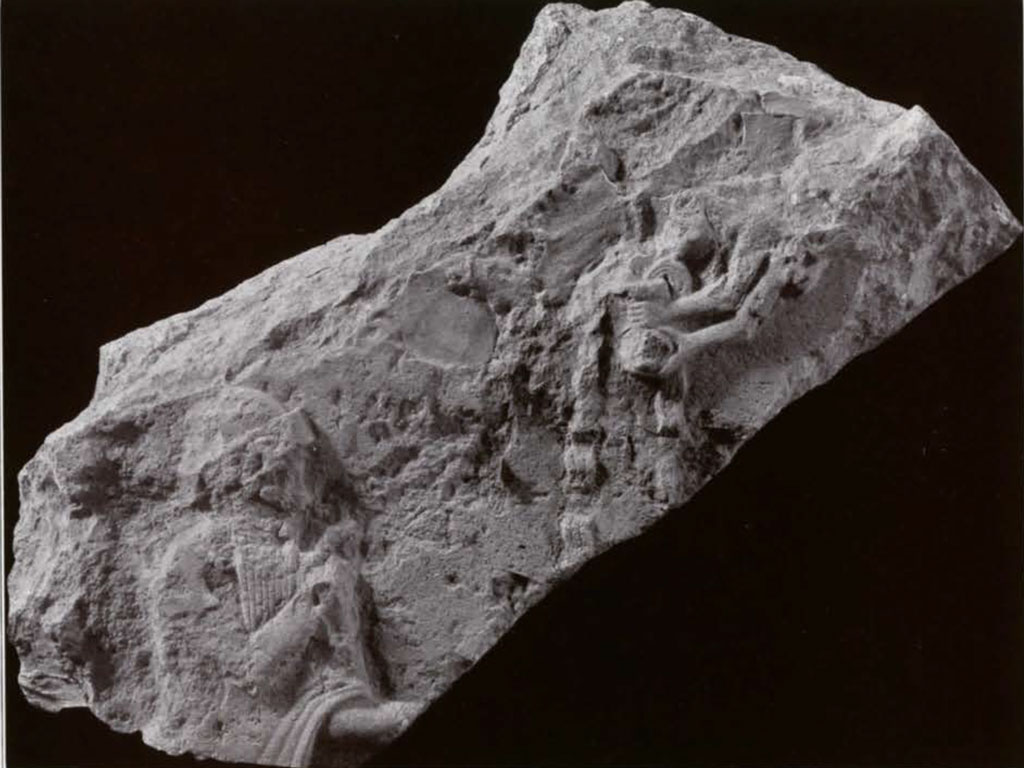

Disconnected Fragments. The Milking Scene.

(Pages 96 and 97)

To complete our survey of the stela some interesting fragments are presented here for their historical relief value. They cannot for the time be connected with the rest of the stela. The first repre¬sents a Sumerian priest shaven and shorn carrying a fly-whisk (?). Mr. Woolley remarks that “those who have lived in the East under¬stand how it was that Satan came to be called the lord of flies.”

The second is a fragment of a divine figure carrying staff and ring. The fine curled beard and the long flounces of the garment are beautifully preserved.

The third belongs to a figure of the king carrying the bronze adze in his left hand, his left arm being covered by the folds of his fringed shawl.

Last of all, the milking scene (page 97, from a cast), a fragment discovered during the first expedition in 1922-1923, may or may not belong to Ur-Nammu’s stela. The type of hair, beard, loin cloth and belt (?) of the cowboy is the same as that of the musicians and butchers. But the milking scene is in the style of a much earlier frieze from Tell-el-Obeid.

“Great as is the historic interest of this record of the building of the Ziggurat, the importance of the monument as illustrating the art of the time is greater still and those fragments where the surface of the stone is well preserved and so the artist’s work can be fairly judged are a striking testimony to the high artistic traditions and technical mastery of the sculptor of the 23rd century before Christ.”

Museum Object Numbers: B16676.28A

Museum Object Number: B16676.28B

Image Number: 8423, 8424

Museum Object Numbers: B16676.18 / B16676.22 / B16676.16 / B16676.25

Image Number: 8415

Image Number: 8416, 8417, 8418

Museum Object Numbers: B16676.45 / 98-9-20 B16676.43

Image Number: 8433

1The original figure of the flying angel is found on the “Bassin sculpté,” of Gudea, cf. Découvertes en Chaldée, pl. 24, fig. 4 and p. 217, also Br. Meissner, Babylonien and Assyrien, Band II, Taf.-Abb. 25.↪