In the JOURNAL for December, 1917, a summary was given of the excavations in the palace of Merenptah at Memphis, being conducted by the Eckley B. Coxe Jr. Expedition of the Museum. A brief description was also given of the probable appearance of the building before its destruction.

Image Numbers: 141816,

150556, 31366

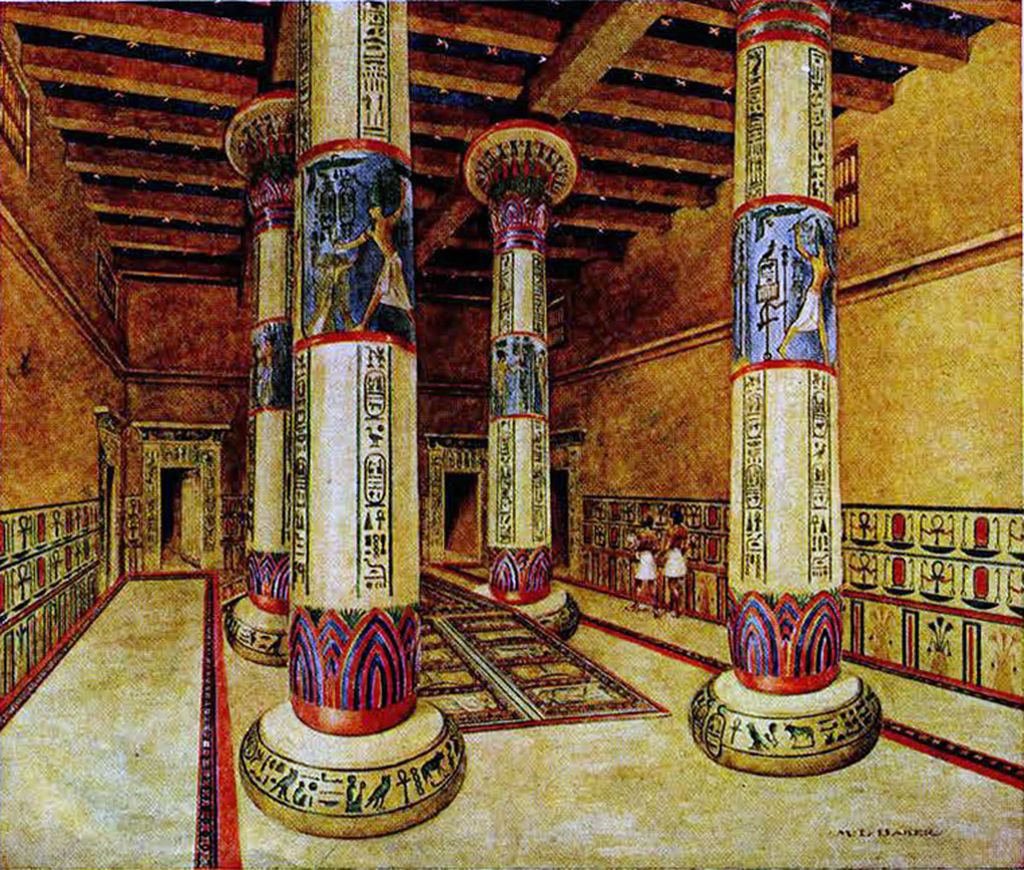

It has now been possible to make a fairly accurate restoration of the principal hall, the great throne room. Restorations of ruined buildings usually have the defect of being largely conjectural and necessarily so, because of the lack of data from which to estimate the vertical dimensions. In the case of the only two other royal palaces thus far excavated in Egypt, that of Akhnaton at El Amarna and Amenophis Ill near Thebes, the plans are very nearly complete but the walls so denuded that little can be said as to their original height. This condition was due to their having been built on an area which was never used after the buildings themselves were abandoned as royal residences, and the walls were subjected to a long period of disintegration. Fortunately the conditions which obtained at Memphis were different. After the end of the reign of Merenptah, there are evidences that the palace was for a time used for other purposes, but this period of occupation lasted for only a few years and ended with a great fire which swept the entire building. No changes were made in the original plan and no reconstructions undertaken. At the time of the fire the palace still stood with its walls and columns intact. The conflagration, however, brought down the columns and the roof, burying the fragments in a bed of charcoal, ashes and mud bricks which was never disturbed.

For our restoration of the throne room we have first a complete plan of the room. The walls remained to a height of from four to five feet, with some of the painted stucco still in situ. All the door sills with portions of the limestone door framings were in position, and in two instances the entire height of the door was intact. The upper parts of the jambs and fragments of the different lintels lay where they had fallen, often badly scarred and split by the heat of the fire. In the debris over the floor were scattered fragments of the columns and while we did not find any one column complete, we were able from the fragments to estimate to within a few inches the height and the scheme of decoration. The entire dais was intact, having suffered only from a loss of most of its brilliant colour and from the wearing down of the ramp where it had been subjected to most use. The floor and the roof were the only portions for which we did not have actual data. The floor was a layer of bricks laid over a foundation of sand. This floor, as we know from a fragment preserved in an adjoining chamber, must have been covered with stucco on which designs were painted. The roof did not present any great difficulties. Had the main walls of the palace been of stone, we would know at once that the roof consisted of slabs laid on long lintels extending from column to column. But as the walls here were of brick, we must accept a wooden roof as the only possible method which could have been used, and the ways of laying a wooden roof are not many. These were the facts we had. Let us pass now to a description of the room based on these facts.

This throne room was the central hall of a building situated at the southern end of a colonnaded court from which it was reached through a great vestibule decorated on the same elaborate scale as the throne room itself. The main door from the vestibule was double, each of the wings turning in bronze sockets let into stone blocks below the main sill. At the top were other bronze fastenings which had fallen with the burning doors to the floor where they were found. These bore the two cartouches with the name of Merenptah. This door was used only on state occasions. At other times entrance was through small anterooms on either side. The view of the throne room which we give here would be that obtained by a visitor standing just inside the door from the eastern anteroom. At the left is the eastern aisle, with a door at the far end leading into a suite of rooms for the king. From behind the farther column projects one of the small flights of steps by which the king mounted the dais, which appears in the central aisle. The doors on the sides lead into storerooms where the official archives were kept. The hall was sixty feet long and forty feet wide. The ceiling was supported on six columns of white limestone twenty-six feet high. The bases Were single blocks of stone sunk below the floor more than a foot and resting on circular foundation walls of rough stones. The shafts contained three pieces while the capital was another single block. At the bottom each shaft was decorated with eight petals in slight relief, the divisions of each petal being alternately blue and gold. They sprang from a broad band of gold. Between the tips of the petals were lotus flowers inlaid with blue glazed faience. Halfway up the shafts were, circled with wide panels on which in relief were scenes of Merenptah slaying his enemies, or making offerings to Ptah, who, besides being his titulary deity, was the great god of Memphis. The details of these were picked out in gold and the inscriptions connected with them were partly inlaid with faience. Around the tops of the columns were the usual five bands, coloured alternately blue and gold. The capitals were of the papyrus type. Starting from a corolla of blue and gold sepals was developed a symmetrical design of cartouches of the king, between long stalks of lotuses, ending at a band of gold around the overhanging edge of the capital. The gold was of heavy leaf laid over red paint.

Between the horizontal motives on the shafts were vertical inscriptions, repeating over and over such formula as “King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Ba-n-ra-mery-amen, son of the sun, Hotep-her-maat, Merenptah, endowed with life forever.” The wording varied, some giving as alternative titles, “Lord of the two lands,” and ” Lord of diadems.” The upper portions of these inscriptions contained always the Horus name of the king, of which we have a great variety. They read: “Mighty bull, beloved of Ptah,” Mighty bull, rejoicing in truth,” or “Mighty bull, slayer of the nine bow people.” Around each base was a horizontal band of inscription of similar wording. All these hieroglyphs were carefully cut out in the limestone and then inlaid with blue faience, the more intricate signs containing a number of pieces. In some cases it was quite evident that pieces of faience had been molded specially for the purpose, such as the war helmets of the king, and wigs and beards of the king or of Ptah.

The walls were first plastered with a thin layer of mud and straw mortar, deep crisscross gashes being made in the face of the brickwork to make this adhere more firmly. The wall was then coated with fine white stucco on which was painted the colour decoration. At the bottom of the walls was a dado representing red and blue niches with panels between. In the panels alternated bunches of papyrus and lotus, symbols of the two political divisions of Egypt. These were in colour generally on a field of yellow. Above this dado were two rows of cartouches arranged in a pleasing pattern of ankh (life) signs with tiny hands holding uas (pleasure) sceptres. Above this the walls were destroyed but we have some evidence that there were various large scenes probably like those on the columns, painted on a background of yellow. High up near the ceiling were square windows, as the lower height of the small rooms along the two sides permitted this clerestory arrangement. Each window was filled with a single slab of limestone, pierced with narrow vertical grooves. The divisions were decorated with alternate cartouches and kekher emblems. Each of the six smaller doors in the chamber were framed with limestone. The vertical jambs had inlaid inscriptions like those on the columns. The lintels always contained two Horus names as well as the two familiar cartouches of the king. These were also inlaid. On the cornices were sun discs of gold with outstretched wings, each feather of one or more pieces of faience and outlined with gold. Some of the jambs had sockets for metal door fastenings.

The dais was at the far end of the hall opposite the main entrance. It extended out level from the inner wall as far as the last pair of columns, and then sloped down to the floor as a ramp. The top of the dais and ramp was covered with reliefs which had originally been highly coloured and perhaps partly gilded. There were in the centre a row of panels, in which bound captives of the various races of people over whom Merenptah had won victories alternated with war bows. The whole was surrounded by a wide border of rekkeet birds and neb signs, emblematic of all nations, and bands of red and blue discs. The background of the design was yellow while blue and red were used for details with possibly, as I have said, gold as well. On the ramp the same scheme was carried out, except that the panels were in two series at the sides with a long inscription down the centre, unfortunately almost entirely worn off by the feet of those who had mounted it.

The floor was apparently covered with white stucco and covered with some design in colour surrounded with borders of discs as on the dais. The ceiling had beams extending the length of the room on which were laid the smaller rafters. The panels were stuccoed blue and dotted with yellow or gold stars, representing the sky.

As I have stated in the former article, this throne room if seen in a brilliant sunlight would have seemed far too garish. However, even when the main door was open, the hall would never have appeared so light as in the restoration. The architect evidently had intended to produce a mysterious gloom which would at once have impressed the stranger with reverence and awe at the grandeur and richness only partly revealed to him.

An audience hour in this hall must have been a spectacle which inspires our imagination. The room filled with slowly moving nobles in their soft white linen robes, panther skins flung over their backs and heavy gold chains and bands on their necks and arms. At the back the figure of the aged Pharaoh Merenptah seated in his richly inlaid chair in all his state robes and crowned with the tall double crown of upper and lower Egypt. Behind him Nubian slaves with ostrich feather fans waving gently to and fro. Perhaps a slight haze of incense over all, and through it slanting the narrow beams of sunlight from the windows high above, here bringing out a patch of gorgeous colour and there glistening on a bit of gold. No other nation could ever have placed their divine ruler in a setting of such splendid dignity and glory.

C. S. F.