MR. ELDRIDGE R. JOHNSON has recently presented to the Museum in memory of Dr. George Byron Gordon, its late Director, a magnificent collection of Chinese carvings in jade, lapis lazuli, and coral, a large crystal sphere of international fame, and a number of other Chinese works of art of great interest and value. The collection is now on exhibition at the entrance to Charles Custis Harrison Hall.

Museum Object Numbers: C681A / C681B

Image Number: 1968-1971

It is fitting that the Chinese collections should contain this memorial. For the Chinese Section was always Dr. Gordon’s special pride and delight ; it was he who launched it in its unpretentious beginnings, who recognized the greatness of this Oriental art at a time when it was but little known and less understood; he who had foresight enough to secure some of the finest of its treasures while the field was still new and comparatively unappreciated in the West. Here may be seen demonstrated as perhaps nowhere else to such an extent, the Director’s great gift of aesthetic appreciation, that instinctive feeling for the very best which he had developed to an unusual degree, and his genius for installation.

Dr. Gordon began the collection modestly with the acquisition in 1913 of a group of small bronzes, blue and white porcelains, and celadons. Only the last are still on exhibition, the others having been stored to make room for the better ones purchased later. 1914 was marked by the acquisition of a really great piece, the pottery Lohan, and a number of splendid stone sculptures. These works of art established the importance of the collection and from this time on each year saw some notable addition to the section.

Museum Object Numbers: C673A / C673B

Image Number: 1948

During 1916 the famous Hsiang T’ang Cave sculpture and the well known Wei and T’ang pedestals were acquired. In 1917 and 1918 the collections were enlarged by the addition of a number of remarkable works, the great stone Maitreya, the gilt bronze one, the two colossal Bodhisattva heads and the three beautiful pieces of Chun Yao Sung pottery. With the acquisition in 1920 of the two stone bas reliefs of the Horses of the Emperor Tang T’ai Tsung—another gift, by the way, of Mr. Eldridge R. Johnson—the Museum attained a position unequalled in Europe or America for its early Chinese sculpture.

A collection of such growing fame could not afford to rest upon its laurels. Dr. Gordon’s great talents were turned to making it constantly better and more comprehensive. Every piece must stand the most rigid tests of beauty no matter what its historical interest or value might be. In 1922 he added a fine votive stela to the group of early sculpture and, most exquisite of all, the gilt bronze Kuan Yin with green patina. A year or two more saw the acquisition of the pair of seated stone lions and the colossal wooden statue of a seated Bodhisattva. Finally, only a few months before his death. he had secured a pair of great stone chimaeras from an early tomb and a colossal wall painting from a Chinese temple the like of which has never been known before, either outside of China or in it. Thus Dr. Gordon left behind him as a monument to his foresight and artistic appreciation a collection of Chinese art which has hardly an equal in the field of early sculptures and frescoes. That this collection ranks today as one of the greatest in the world is due to Dr. Gordon’s unerring judgment in selection and to the generosity of those who had faith in that judgment, who loved the art of the Orient, and who felt a pride in the collection that in so short a time had, with their help, reached such notable rank. What more appropriate than that a group of objects belonging to the last art period of China—and one hitherto unrepresented in the collections—should bear the name of him who first began those Oriental collections and raised them to such heights; or what more fitting than that the donor should be one whose name was already connected with some of the outstanding works of art in the collections.

Museum Object Numbers: C673A / C673B

Image Number: 1949

The memorial consists of twenty-eight objects of Chinese art, the most notable of which are the eighteenth century carvings from the workshops of the Emperor Ch’ien Lung and the fascinating crystal ball said to have been once the treasure of the Empress Dowager of China. Included in the collection are a fine bronze tripod and a Chinese painting of the Ming dynasty. A group of interesting ritualistic objects of early jade types completes the collection and may serve as the subject of a special study later on.

The following reproductions give some idea of the rich beauty of material contained in the Gordon Memorial and of the exquisite workmanship involved. Unfortunately they cannot convey the full glory of the colour nor the unctuous quality of texture for which these masterpieces of late Chinese art are noted.

The Chinese have always had an intense love of jade and a peculiar reverence for it: to them it was the gem par excellence, something extremely precious, full of beauty and virtue. The word indeed was almost a synonym for beauty, a beautiful woman was often described by the term “a woman of jade, ” and to say of a man that his “countenance was like jade” was to pay him the highest compliment. In very ancient times ritualistic objects were made of jade to be used in the worship of the cosmic deities of Heaven, Earth, and the four cardinal points. Badges of office and symbols of rank were made of this stone, symbolic carvings of it formed the pendants of the girdle ornament which every gentleman wore, and at least six jade objects of symbolic significance surrounded and protected the body in the coffin. The pieces used in ancient ritual relied upon form and intrinsic beauty of material for their effect, being always simple in shape and unadorned, for, as the ancient Chinese said, “Acts of the greatest reverence admit of no ornament.”

Museum Object Numbers: C674A / C674B

Image Number: 1950

However, as the art of sculpture and especially that of painting developed in China the influence of the pictorial began to be felt in other fields, and artists made carvings in jade for the purpose of ornament alone. Thus a new class of objects came into being founded upon love of artistic design rather than religious symbolism, though the subjects represented were frequently taken from Buddhist or Taoist lore. In the eighteenth century, just about two hundred years ago, a tremendous renaissance of art took place under the enthusiastic patronage of the Emperor Ch’ien Lung, and the Chinese lapidary came into his own. No one has ever surpassed him in taste or skill. He revelled in the richest of materials and fashioned them into palace ornaments of amazing beauty. The Emperor Ch’ien Lung himself wrote poems to be engraved on some of the finest pieces. From the eighteenth century to the present day not only jade of all colours but other hard stones of semiprecious nature have been utilized by clever hands, malachite, rose quartz, lapis lazuli, agate, marble, crystal, and coral.

In the olden days jade was indigenous to China. The ancient ritualistic and tomb objects were made from boulders found in the river beds of Shensi, Ssu-ch’üan and Honan and from slabs quarried in the mountains near Ch’ang-an, the ancient capital. These objects are now rather opaque owing to burial, of dull tans and greens, ivory whites, yellows in all shades of ochre, and ash colour, or a rich dark brown which the Chinese have been fond of declaring was due to blood stains from the corpse, an unfounded but pleasantly gruesome statement. About the first century A.D. the supply of native jade began to run low and it was imported in ever increasing quantities from Khotan and other places in what is now Chinese Turkistan. By the tenth century the native supply seems to have been completely exhausted and jade is not now found in the soil of China. Turkistan continued to quarry huge quantities of jade, however. In the K’un Lun mountains behind Khotan are rivers still known as the Black Jade River (the Karakash), the White Jade River (the Yurungkash), and the Green Jade River (probably the Yangi Darya). Indeed, the quarries there were not deserted until 1852, during a Mohammedan revolt against Chinese rule. The jades from Turkistan were of various hues, gray green, or celadon, white (mutton fat), black, brown, reddish brown, yellow. Many of them have yellow and brown spots, due to a penetration of oxide of iron. Some of the greens are very rich. That Ch’ien Lung used great quantities of Chinese Turkistan jade we can read in the records. We are told that in 1764, the 29th year of his reign, the governor of Yarkand sent him thirty-nine huge slabs of jade to use for making musical stones—the total weight of the slabs amounting to 5300 pounds.

Museum Object Numbers: C674A / C674B

Image Number: 1951

The Chinese name for jade is yü. Our term jade comes from the Spanish ” piedra de Hijada” or “stone of the loin,” so called because it was supposed to have medicinal virtues in troubles of the kidneys. The word jade did not occur in our language until its introduction into England by Sir Walter Raleigh in the 16th century.

There are two kinds of yü or jade recognized by geologists, nephrite and jadeite. The old jades of China which we have so far mentioned were all nephrites (silicates of calcium and magnesium). Ch’ien Lung had, however, another field to draw upon for his jades, one first discovered in the thirteenth century—Burma. The Burmese mines are the chief source of jade today. The jade quarried there is of the type called jadeite (silicates of sodium and aluminium), harder, more granular, and more translucent than the nephrites and of a brilliant apple or emerald green. This is the famous fei ts’ui jade of commerce. Some of the most beautiful of the pieces in this collection are made of this fei ts’ui. The fresh tender green colour is due to infiltration of chromium. Pure jadeite is a stainless white.

Lapis lazuli, or azure stone, has been found in China, Tibet, and Persia, but the best known mines are in Badakshan in the valley of the Kokcha River, a tributary of the Oxus. These mines were in operation in the thirteenth century, for Marco Polo visited them in 1271. It is probable that Ch’ien Lung obtained his supplies from this locality and perhaps from a region in Siberia near the western end of Lake Baikal. The stone is very opaque—and comparatively soft. Crystal, on the other hand, is extremely hard. It is a colourless, transparent variety of quartz, limpid, and cold to the touch. In fact, the name crystal comes from the Greek word meaning ice, given it in the belief that it was water which had been exposed to extreme cold. The source of Chinese rock crystal was India.

Museum Object Numbers: C676A / C676B

Image Number: 1955

It is a well known fact that the most beautiful of the eighteenth century works of art, including carvings in jade and other stones, were looted from the Imperial Summer Palace, the Yüan Ming Yüan near Peking, during the T’ai-p’ing rebellion of 1849 to 1864, and especially after the Anglo-French occupation of Peking in 1860. There is no doubt that many of the most priceless objects were at. that time wantonly destroyed. Many, however, escaped harm and made their way to Europe or into private collections in China. These pieces can no longer be in every case identified with certainty but their exquisite workmanship, their beauty and grace of composition, and the princely value of the material leave little doubt as to their origin. The Gordon Memorial contains several of the most. beautiful examples known.

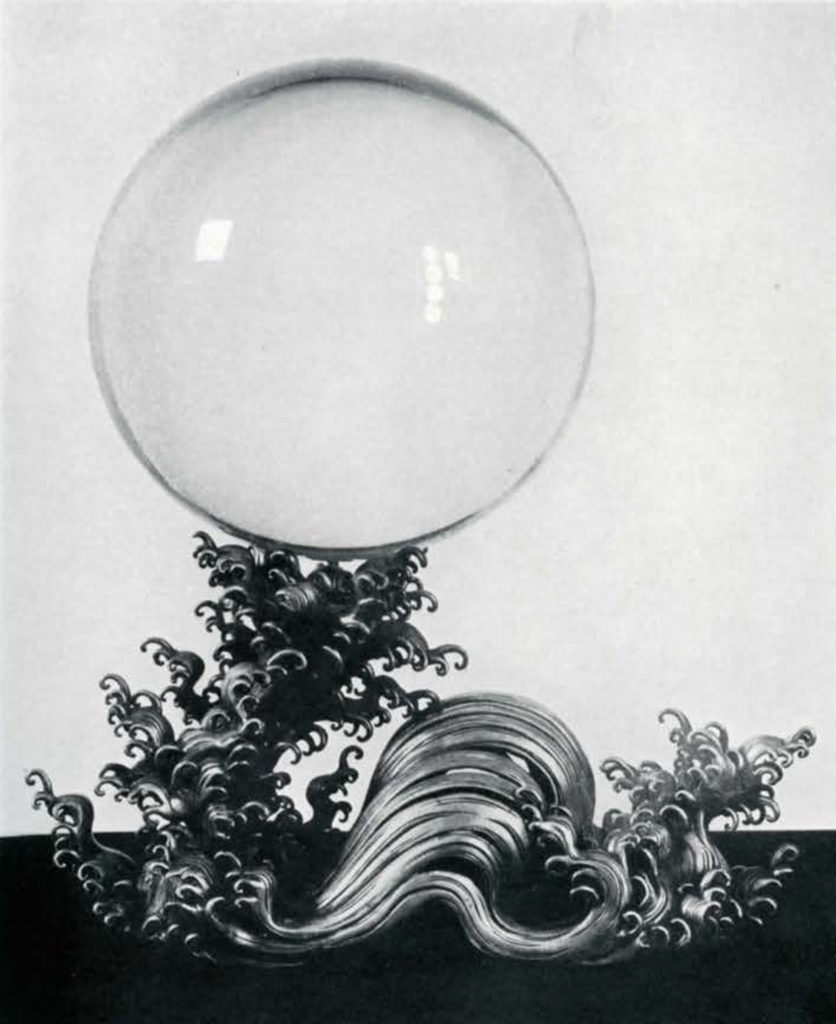

Crystal Sphere

The sphere of rock crystal given by Mr. Johnson in memory of Dr. Gordon is one of the most beautiful and perfect known, there being, in fact, very few others in the world which can com-pare with it in size, flawlessness of material, or perfection of craftsmanship. The ball has been fashioned out of a very large, clear, silvery white crystal, is ten inches in diameter, and weighs about fifty pounds.

Museum Object Number: C677A / C677B

Image Number: 1956, 1957

A sphere such as this is a triumph of skill and patience, as the Chinese had no machinery and only the simplest of tools. It represents years of painstaking work with emery and garnet powder and water, while the ball is kept constantly revolving in a semi-cylindrical iron vessel of the size to which it is to be ground.

This sphere may have been fashioned in the Chien Lung Period when the love of such ornaments became a passion in imperial circles. At any rate it became well known during the nineteenth century, and has been popularly spoken of as “The Dowager Empress” because it was one of the treasures of the Imperial Palace, said to be greatly loved by the Empress Tz’u Hsi. It is the second largest crystal hall in existence, so far as may be ascertained.

Crystal spheres were employed in the west for “scrying” or crystal gazing, but apparently the Chinese never used such balls as these for that purpose. They were merely exquisite ornaments for the palace. They were mounted usually on silver stands which sometimes represented dragons. This one has a stand of silver representing a wave breaking into foam, on the crest of which the sphere floats like a limpid bubble. From some angles the ball appears to have a silver ring around it and at such times it seems suddenly strange, a thing of elfin beauty almost uncanny. In its clear depths is held all the magic mystery of captured moonlight, all the fascination of familiar things transformed and ethereal.

Museum Object Number: C675A

Image Number: 1954

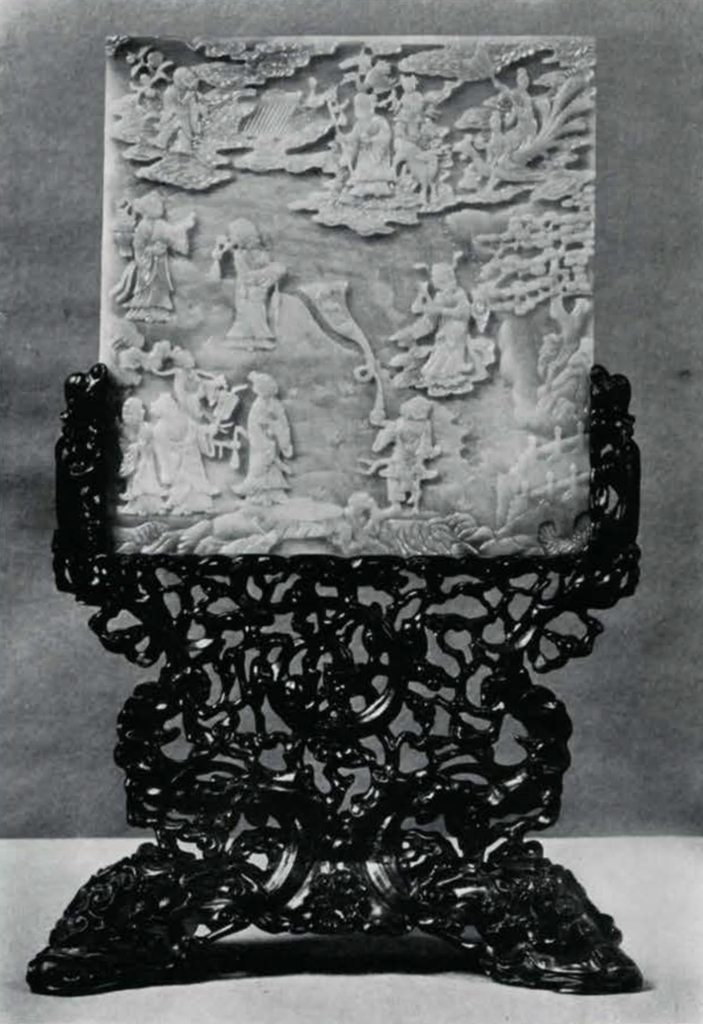

Table Screen of Green Jade

This is one of a pair of exquisite green jade table screens purporting to have been carved in the Imperial workshops of the Emperor Chien Lung. It is made of a slab of jade about nine inches square, cut so thin as to be translucent, and the deliciously fresh emerald green colour it exhibits with the light behind it delights artist. and layman alike. It is unusual in containing some cloudings of pale lavender also, and near the edges at top and bottom a tinge of amber yellow. Against the light the little figures cut in low relief appear rich and dark like the pattern of a cut velvet.

The scene represented on the front of this illustrates a subject of Taoist lore which is a great favorite in China, the eight Immortals gathered in a landscape to pay homage to Shou Lao, the God of Longevity. On the bank of a stream are assembled seven of the Immortals, Lan Ts’ai-ho with her basket of flowers on her back, Lu Tung-pin with his sword and a tassel hanging from it appearing over his shoulder, and Ho Hsien Ku, patroness of housewives, with an enormous flower on a long stem. Chang Kuo Lao, patron of artists, appears with his queer Taoist bamboo musical instrument, next to him is Chung-li Ch’uan the fat man with bare stomach and a fan. then Han Hsiang-tzu with his flute and Li T’ieh-Kuai hobbling on a crutch and holding up his pilgrim’s gourd out of which streams a funnel of light. The eighth Immortal, T’sao Kuo-ch’iu, is seen crossing the stream on a cloud merrily playing his castanets. Above, in the clouds, may be seen Shou Lao, the god with the high skull, surrounded by emblems of immortality and attendants with such emblems.

Museum Object Number: C678

Image Number: 1959

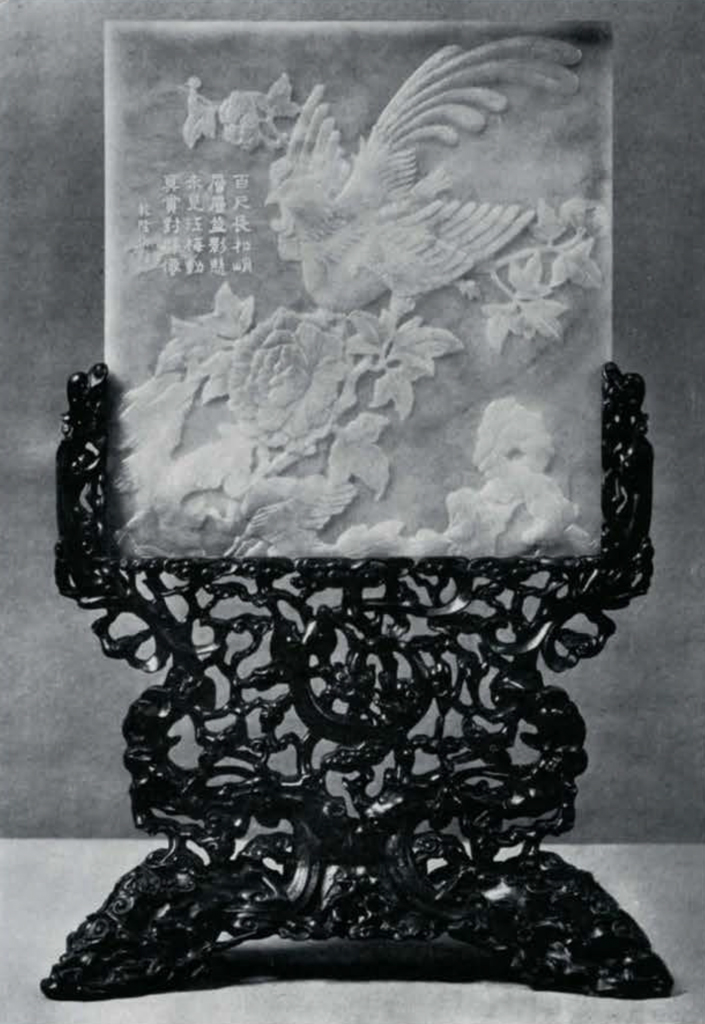

Back of the Screen

The carving on the reverse is seen to be of quite different character, a pictorial design of phoenix bird, peony tree and rocks, all done in very low flat relief. At the upper Left is engraved this short beautifully written poem:

“On the tops of pine trees one hundred feet tall,

Layer upon layer their shadows are hanging—

Although we are unable to see the Plum River moving,

Indeed we enjoy being together with a group of immortals.

The characters are inlaid with gold. The beauties of the jade itself, its fresh green with soft lavender cloudings, may be understood better from this picture of the back than from that of the front where the more sharply cut relief somewhat obscures the material.

Table Screen of Green Jade

The second one of this pair of exquisite jade screens is the same as the first in size and material, indeed it seems to have been made out of a piece of jade contiguous to the other, the cloudings and veinings corresponding exactly but reversed for the carving. The scene carved on the front, the meeting of the Eight Immortals and Shou Lao, seems at first glance also to be identical with the other but reversed. It varies only in certain minor details.

Museum Object Numbers: C685A / C685B

Image Number: 1975

The emblems on these carvings are all symbols of long life. The nine personages figured, some mythical, others historical in origin, are all supposed to have obtained immortality in some strange manner. The pine tree, the deer, the crane, the peach and the lung chih fungus are all symbols of longevity. It was a favorite subject with the Chinese.

The artistic quality of these pieces is very high. The composition of the obverse in each is quaint and decorative; the variety in depth of relief as a means of suggesting perspective affords richness in colour as well, and the cutting of the little figures and their accessories is done with taste and charm.

Reverse of the Second Screen

The reverse of this screen bears a design similar to but not identical with the reverse of its companion. The poem engraved in the upper left corner reads as follows:

“In the bluish green rays of the inclined sun

The graceful clouds are sailing by the home of immortals.

Glorious happiness is in the Nan-hsiang society.

I wish you an eyebrow-longevity of ten thousand years.

Museum Object Number: C684A / C684B

Image Number: 1974

Here, likewise, the characters are delicately inlaid with gold. An “eyebrow-longevity” in Chinese means an extremely long life. The wish here expressed reveals the probability that this pair of screens was made for a birthday gift from the Emperor to a friend.

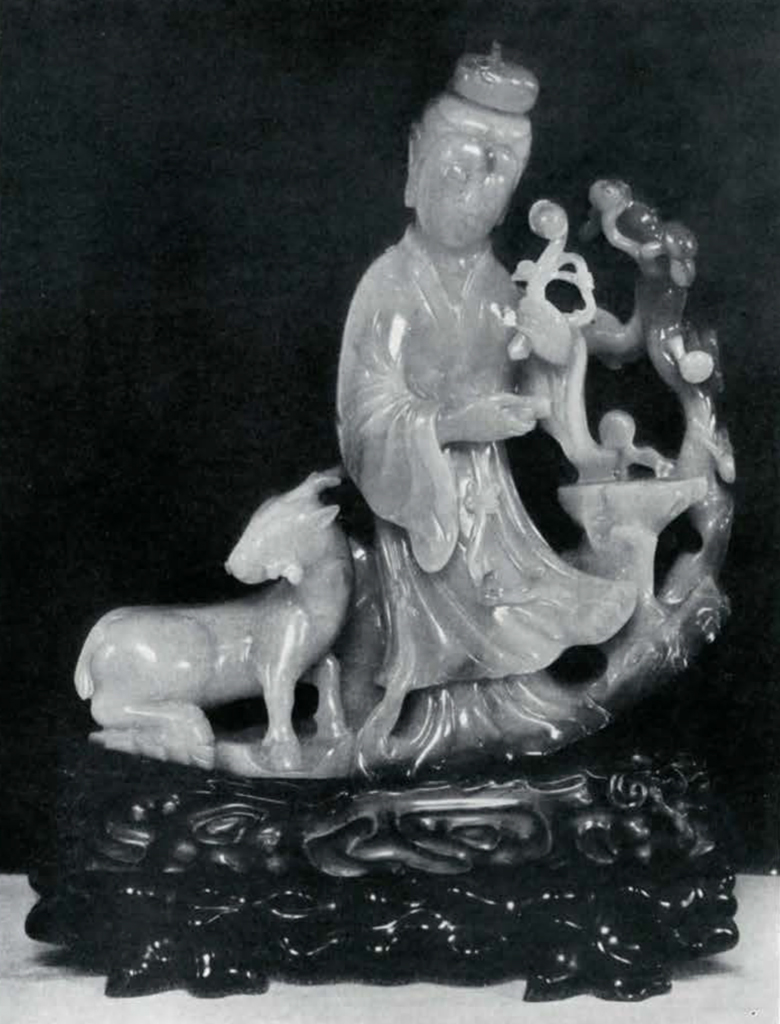

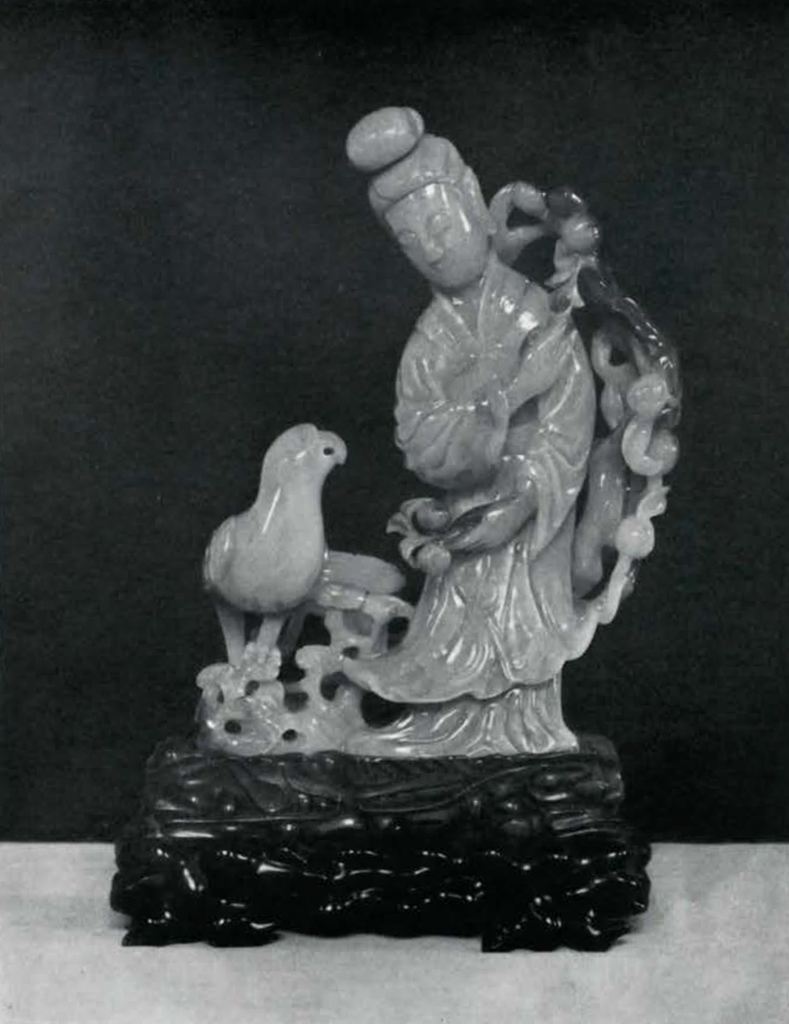

Lady with a Deer

This carving and its companion piece are made of an unctuous granular gray jade with a vein of brilliant leaf green and a streak of amber brown. Under the Emperor Ch’ien Lung of the eighteenth century it was quite the fashion to give presents of precious jade, and thereafter such imperial gifts as these were bestowed upon occasions when congratulations were in order, such as a betrothal, a marriage, the birth of a grandson, or the appointment of a prince to high office. It seems likely that these two are marriage gifts. This one represents a slender female figure standing by a pine tree which curves up on the right. The figure bends gracefully toward the tree. By her side, on the left, is a deer with the ling chih, fungus of immortality, in its mouth. The figure holds a scroll and a ju-i sceptre while from the rocks at her feet spring more fungi. The carver has exhibited great ingenuity in making use of the natural veins of colour in his piece of jade and has so contrived as to bring the streak of brown into his ground and tree trunk and has utilized the bright green veins for ornaments of dress. Such carvings as this were often of a subject involving a rebus, or pun, which was actually an indirect equivalent of such an expression as our “good luck and best wishes.” The fungus ling chih suggests ling, “high age”; the name for deer is lu, calling to mind another Its which means “prosperity”; the ju-i sceptre is equivalent to good wishes because the phrase ju-i means “as you wish” or, “may your desires be fulfilled.” The pine tree is a symbol of longevity. To the unsuspecting the object is merely a beautiful jade carving. To those who can read its meaning it says, “Wishing you long life, prosperity, and the attainment of your desires.”

Museum Object Numbers: C680A / C680B

Image Number: 1964

Lady with a Parrot

This, the companion piece to the Lady with a Deer, is of similar material and was probably cut from a piece of jade contiguous to the other. The scheme of composition is much the same. Curving up at the right is a peach tree loaded with fruit. A young woman stands beside it bending gracefully toward a huge parrot on the left which is turning its head to look up at her. Her hands hold branches with peaches on them and from the rocks below rise bunches of the sacred fungus. Again, as in the other piece, the amber brown streak has been cleverly utilized so that the trunk of the tree comes in the brown vein while peach branches, fruit and dress ornaments are carved out of the green streaks and veins in the jade.

In this case also a rebus may be read. The peach tree is allegorical of a happy marriage because it recalls a well known poem in the “Odes” in which a bride is likened to a graceful peach tree. The pat-rot, thanks to a famous anecdote about it, has become a symbol of warning to wives to be faithful to their husbands. The peach itself and the ling chih fungus are both symbols of longevity. Thus the carving may be read, “May you live long, have happiness in wedded life, and always be a faithful wife.”

These carvings rest upon old carved ivory plaques themselves of rare size and beauty, the ivory having aged to a warm toasted brown and cream tone and acquired a most pleasing texture. The ivory plaques are in turn supported upon stands of carved teakwood.

Statuette of Kuan Yin

Museum Object Number: C687A / C687B

Image Number: 1979

Few jade carvings are comparable to this in size, for it is twenty-six inches in height and carved out of one enormous block of jade. The jade is a glorious gray green running to a brilliant leaf green in places and has cloudings of a pinkish gray and frequent spots of yellow brown, like rust, these last being due to oxide of iron. It is a truly regal piece, full of quiet dignity and simple poise. Kuan Yin, Buddhist goddess of mercy, stands with eyes downcast, a dreamy expression on her face, her mantle drawn together in front where the right hand is visible holding a rosary. The drapery is arranged in simple, rather flat folds, the ends flaring out above the ankles as if in a faint breeze. The goddess wears a crown and a short shoulder cape with a hood, the latter being drawn up behind over the back of the crown to lie in two heavy folds on top of the head. It is a beautiful example of modern work.

Lady with a Hare

A carving in the same style as the two marriage gifts but probably of more recent execution. The jade is white with a greenish tinge which becomes concentrated in certain areas into a brilliant green. The structure appears very granular and where the carving is thin, as in edges of folds or margins of leaves, the translucency is quite marked. The subject is that of a young woman holding a hare on her left hand while waving a spray of foliage and fruit above the little creature. The two trees rising behind her appear to be banana trees and the fruit the lady holds may be a bunch of young bananas. The hare was a symbol of the moon and often figures in Taoist lore as pounding the elixir of immortality in a mortar or held in the arms of a genie or fairy of the moon.

Museum Object Numbers: C686A / C686B

Image Number: 1977

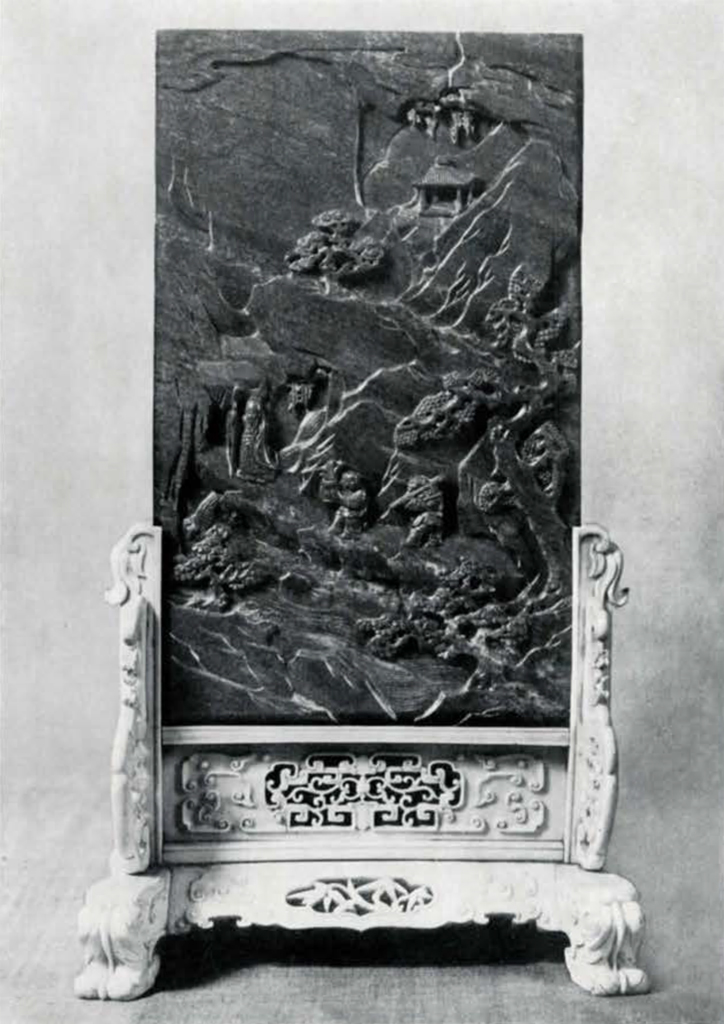

Imperial Table Screen of Lapis Lazuli

One of the richest materials used by the Ch’ien Lung artists for their carvings was lapis lazuli. The Gordon Memorial Collection is fortunate in possessing a pair of very fine screens from the Imperial workshops. These palace pieces are oblong slabs of the glorious blue stone nine and three-quarters inches high, six inches wide and one-half inch in thickness. The front in each case is carved with a pictorial design representing a sage with two attendants climbing a mountain beside a rushing stream while high above on a ledge of rocks appears a tiny mountain pavilion. The scene is carved in low relief with great simplicity of line and plane which is heightened by the richer detail of the foliage of a few trees. The scenes on the two screens are not identical but are variations of the same subject and balance each other. The backs show a smoothly polished surface, engraved in each case with an original literary composition by the Emperor copied from his own handwriting. The translation is as follows:

“Exactly for the whole day we listen to the mango-bird crying. Over the Tan Chang pavilion the disorderly leaves of red almonds are spreading.

In the wide river the night-rain falls and the tide begins to grow.

Far over the islet the mist and grass become green again.

Imperial Table Screen of Lapis Lazuli

This is the companion to the preceding, varying from it only in the arrangement of the mountain scene on the front and the literary composition on the back. The poem on the reverse of this reads as follows:

“Facing towards the south-west my eyes look at the sky of a thousand Li.

Thinking about the present and past, I feel small and sad. Green pine trees carry our sight far into the fair and white clouds,

Like a piece of floss silk are the boundless flat mountains in layers.

Museum Object Numbers: C679A / C679B

Image Number: 1961

Vase of Lapis Lazuli

This vase is fashioned out of a huge block of the precious material and measures eleven inches in height without its carved ebony stand. The blue is somewhat lighter than that of the two screens and the stone is shot with veins of dull green and cream and full of specks of iron-pyrites looking like gold dust sprinkled through it. In form the vase is cut to represent a section of rustic tree stump upon which appear, carved in fairly high relief, rocks, branches of a gnarled and crooked maple tree, and foliage, vines, and flowers. The arrangement is naturalistic, the rocks rising at the foot of the vase and the tree growing out of them. The trunk of the maple throws its bold angles across the body of the vase and raises its branches into clumps of foliage around the top. The sacred fungus, symbol of longevity, and chrysanthemum flowers, symbol of autumn, grow upon the rocks. Around the branches twine vines whose leaves and tendrils hang from the top of the vase like ends of rope among the maple foliage. The magnificent proportion and design of this vase suggest that it, too, is a product of the Imperial workshops of Ch’ien Lung.

A Fairy on a Phœnix

This odd and delicately beautiful carving in coral represents a slim sweet-faced Taoist fairy standing on the back of a great phoenix bird. The artist who saw in an awkward piece of branching pink coral this charming and unusual bit of fancy was deserving of the honour of carving an imperial piece. For this and its companion carving, the fairy on a dragon, claim to be from the Imperial collection. However that may be, the simplicity of the composition and the restraint and refinement of design place this piece far above the majority of such carvings. The little figure is full of dignity and grace and the decorative phoenix with its conventionalized plumage is a fitting accompaniment. The phoenix, it must be remembered, was the symbol of the Empress. The collar of leaves worn by the sylph indicates—as if there were any necessity!—that she is not a mortal.

A Fairy on a Dragon

The companion carving of the pink coral fairy on a phoenix is this sylphlike figure riding on a royal five-clawed dragon, the symbol of the Emperor. The same ingenuity shown in trans-forming a rough branch of coral into a figure of quaint grace and refinement is found here also. The figure is extremely elongated and the dragon more realistically treated than is the phoenix in the other case. This fairy wears not only a cape but a girdle of leaves as well and holds above her head a branch of flowering peony, a huge blossom of which sticks out above her high-dressed hair. The peculiar appendage at her shoulder is a mass of her long hair flying in the breeze.

The height of this pair of carvings is rather unusual, each measuring over eighteen inches.

The peculiarly elongated character of these pieces has its origin in no “modern” effort to be original but simply arose out of the nature of the material of which they are made. Their somewhat fantastic beauty is partly the result of chance and the desire to use a certain awkward branching of the coral to carry out a necessary element of anatomy or some accessory.

Museum Object Number: C682

Image Number: 1150

A Fairy with Flowers

This coral carving is rather more ornate than the others and is doubtless of recent manufacture. It represents a female figure seated on a rock over which grow clusters of the ling chih fungus. The body is twisted sideways from the hips and on her left arm she holds a huge pot with a veritable tree growing in it—a peony tree loaded with heavy waxlike blossoms. Behind her there grows up from the rock another peony tree which twists at her waist, winds up over her shoulder, and rises high above her head in a profusion of great flowers. At her feet is a tiny barking Fu Dog.

There are passages of much beauty in this carving. The line of the arm holding the flower pot as seen from the back is exquisitely beautiful, and some of the flowers are carved with such power that one can almost smell the heavy perfume. The colour of the coral, a rich pink, is very striking.

Bronze Tripod

An unusually large specimen of great dignity in line and proportion. In China ancient bronze vessels were often among a family’s most treasured heirlooms, passed down from father to son for many generations. Some have thus been in Chinese households for many centuries, others have been recovered from early tombs. In recent years, during the building of various lines of railroad, many which had been buried in the earth have come to light, especially in Honan and Shensi provinces. It is not known from what locality this vessel comes. It is a wide shallow bowl raised on three short hollow legs and having two upright handles. Apparently these handles are hollow also. They bear traces of an archaic dragon design. The bowl has a wide flat rim. A remarkable feature about this bronze is its amazing patina, which is in the form of a malachite incrustation as much as an inch thick in places. It seems to be superimposed upon the bronze rather than an actual breaking down of the alloy near the surface, for much of it has been scraped off leaving the bronze itself, to all appearances, none the worse for its loss. The malachite looks like a hardened flow of molten green metal and the polished green of its sluggish lumpy surface adds greatly to the rich colour effect of this fine bronze.