A Bronze Age Cup Decorated with an Octopus

NO one can travel far in the Eastern Mediterranean without encountering the octopus. On the table d’hôte of seaside restaurants are served neatly cut sections of his long arms, which taste, if one has the temerity to taste, something like our scallop. On wharves young boys swing sprawling masses of pulp high above their heads and slap them with all their might against the ground. They are pounding the octopus to make it tender. And on still summer mornings fishermen are seen working their boats in and out of the tiny coves that fringe the Greek islands. They are hunting the octopus in his lair. One man hangs over the stern and looks through a glass-bottomed pail; the other gently propels the boat.

Museum Object Number: MS5701

Image Number: 5131

Since men made boats they have hunted the octopus so—if we except the glass-bottomed pail. Throughout the bronze age, potters, jewellers, and painters of frescoes used the octopus as a decorative motive. In the earlier phases of the potter’s art, the whole cove was represented with fronds of seaweed floating about its margins and the smaller fry of marine life filling in the picture. In the last period of the bronze age, the figure of the octopus is so stylized that it is little more than a figure eight with two eyes and four arms which cover in even loops the entire surface of the vase. The octopus on the Museum’s cup, page 73, is from an intermediate period. The creature is depicted in a manner that is both lifelike and decorative. The number of arms is altered in the interest of symmetry; the suckers are rendered by neat rows of dots in superadded white.

The vase is made of admirably levigated clay; its surface is highly polished. It is not a Cretan piece, for this shape of high stemmed cup was little used in Crete, not indeed until the very end of the bronze age. It was popular, on the contrary, at Mycenae and other sites on the mainland and also at Rhodes, where recently cups of this shape with exactly the same disposition of bands on the foot and with a single octopus symmetrically arranged, have been brought to light by the Italian excavators. The cup dates from about 1400 B.C.

Red-Figured Lekythos by the Berlin Painter

Museum Object Number: MS5706

Image Number: 2938

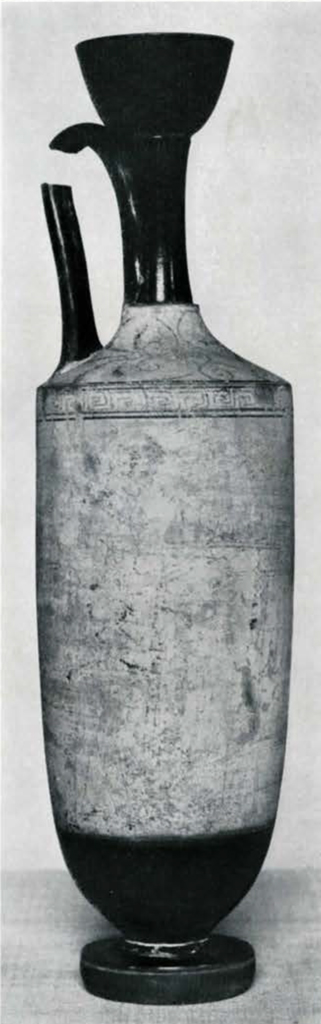

This vase was purchased for the Museum by Dr. Gordon shortly before his death. It is a minor work of a great painter. His name is unknown but the importance of names and of signed vases is greatly diminished by the studies of Mr. J. D. Beazley of Oxford, who has pointed out that some of the finest Greek vases extant are unsigned. Mr. Beazley has in fact revolutionized the study of Greek vases; by marvellous acumen and the careful observation of the most minute details of the vase-painter’s art, he establishes the style of a given painter and groups together the vases by his hand. The painter is named for his chef d’oeuvre or for his best known piece. So accurate is Mr. Beazley’s method that his attributions are seldom questioned.

To Mr. Beazley I owe the identification of this vase. The painter is named “The Master of the Berlin Amphora,” or, for short, “The Berlin Painter,” after a masterpiece of Greek vase-painting, amphora No. 2160 in Berlin. No less than 149 vases have been attributed to this master by Mr. Beazley. Six more, one of them a stamnos in our Museum, are attributed to his school. Very few works of this painter are in America, so that it is a matter for congratulation that we have secured a work by the hand of the Berlin Painter as well as one from his school.

Our lekythos was formerly in the collection of Baron Giudice in Girgenti. It is decorated with a single figure, that of a Maenad in rapid motion. She wears an Ionic chiton of sheer material, edged at the top with two black lines. The folds into which this garment falls below the waist are represented by groups of straight lines terminating below in the ladder contour. The garment is pinned on the shoulder to form sleeves. Over the chiton is worn an himation or shawl of thicker stuff with tassels on the corners. The hair is caught up behind by a diadem. The figure resembles closely that of Europa on a bell-krater in Corneto, painted by the Berlin Master. The grave and gentle figure has the freshness and engaging charm of the ripe archaic style of about 475 B.C.

“His people,” says Mr. Beazley of the Berlin Painter, “have the charm of early youth, long limbs—winged things and creatures

‘Pard-like, beautiful, and swift.'”

Two White Lekythoi from Eretria

In Aristophanes’ incomparable picture of women in parliament,

the Ekklesiazusæ, the ladies pass a law that young men should be compelled to make love to old women. A scene ensues between youth and a beldame, she demanding under the new law that he make love to her.

“But I fear your lover,” says he.

” Who?” she asks.

” The ablest of the painters,” he replies.

“And who is he?”

” The man who paints lekythoi for the dead.”

With an Athenian audience this was equivalent to saying that the man interested in her was the undertaker. A few lines further

on the saucy boy tells her to prepare her bridal couch, but in so doing he uses the phrases and prescribes the rites for preparing the funeral bier.

“First strew it well with marjoram,

“Lay beneath four well-crushed branches of the grape,

“Bind on the fillets, set beside it lekythoi.”

These two passages which doubtless made the Athenians shake with laughter are of great interest for the modern archaeologist, as they show that lekythoi were made for the dead and were set beside funeral biers.

Museum Object Number: MS5676

Image Number: 3093

Museum Object Number: MS5676

Image Number: 3092

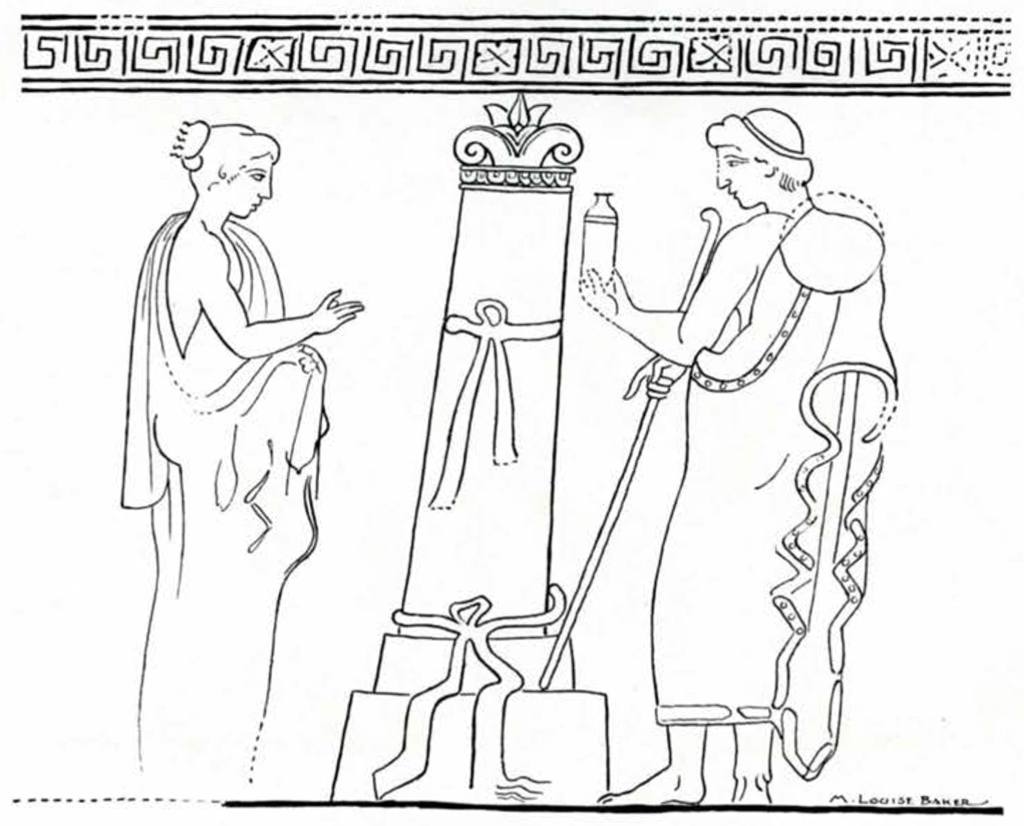

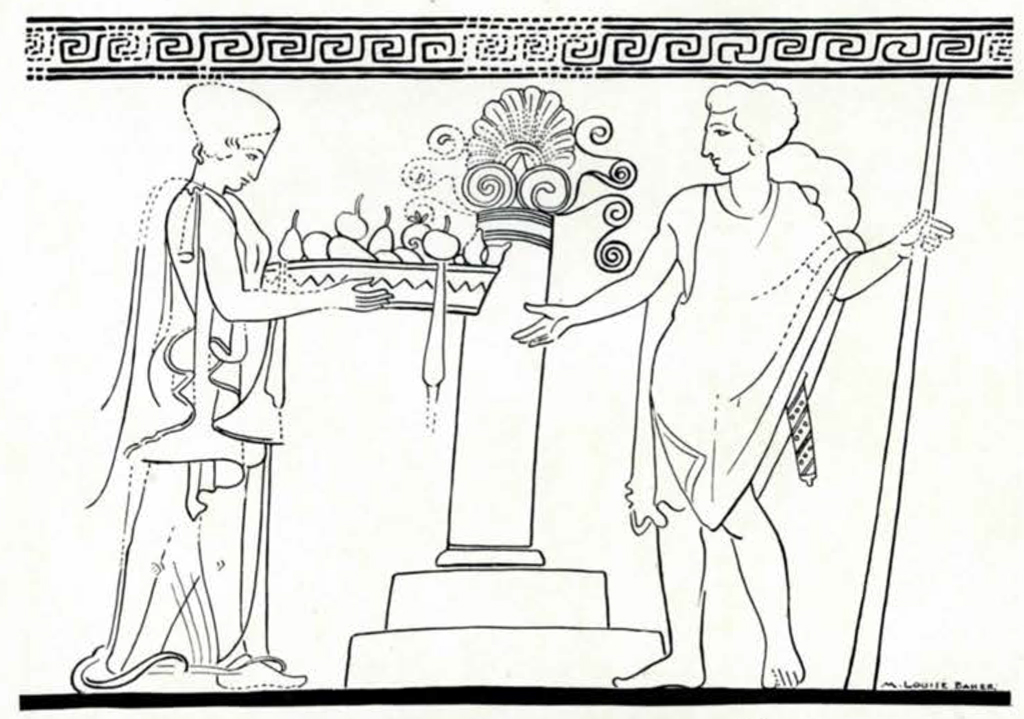

The class of vases to which Aristophanes had reference has been identified beyond a doubt, not with the red-figured lekythoi like the foregoing but with the so-called white lekythoi, vases which were mainly covered with a white slip, and decorated with scenes relating to the cult of the dead.

Two of these funeral lekythoi the Museum bought recently from an American traveller who purchased them in 1893 at Eretria on the island of Euboea; the peasant who sold them stated that he had discovered them in a tomb adjacent to the theatre and that they lay, both of them, upon a sarcophagus.

Neither vase is in a perfect state of preservation. In the case of the lekythos on page 76, the white slip is flaking off from the clay beneath it. Some pieces which had entirely scaled away have at some period been glued to the surface of the vase and retouched. This damage had luckily been confined to a small area just above the feet of the girl. On the other vase the slip has not flaked off but has worn or been rubbed away until in places the lines of the picture are difficult to trace. But in spite of their imperfect preservation—and white lekythoi because of their fugitive slip are rarely entirely undamaged—these vases are excellent representatives of their class.

Museum Object Number: MS5677

Image Number: 3096

In a scholium on Plato’s Hippias Minor, a lekythos is defined as an Attic word for the vase in which unguents for the dead were carried. The word for unguents is a general one applicable to any costly oil or perfume. Such rare essences would not be squandered ; a very little would do to anoint the dead or set beside the bier. Nor would the bottle be filled full when it was carried to the grave and left as an offering, or when it was tossed with its contents on the blazing pyre, a practice attested by the clear signs of a second firing which have been recognized on some of these lekythoi. With an eye to the thrifty character of his clients, the potter sometimes made these vases with false bottoms, and one such is our vase on page 76. Half way up the shoulder of the vase may be traced a break where what was in reality a very small bottle holding only a few ounces was set into the lekythos proper. The false bottom comes just above the line of the girl’s head on the outside of the vase.

The subject of the decoration is the same on both vases, the presentation of offerings at the tomb. In the center a funeral shaft, on the left a girl, on the right a boy. It is a picture which is repeated over and over on these vases but never twice alike. The funeral shafts are never alike; the sashes (such as Aristophanes’ impudent boy would have the old lady bind to her couch) are tied on differently; the offerings vary; there is infinite variety of costume and of pose. On one of our vases the girl offers a basket of fruit while the boy stands quietly by, a chlamys and quiver slung over one shoulder. On the other it is the girl who stands quietly by with outstretched hand, while the boy wrapped in a long himation and standing with his back to the spectator gravely makes his offering of a flask. This flask, it will be noted, is not a lekythos, which shows that other vases than lekythoi were used for offering to the dead.

The grave monument on the vase illustrated on page 79 is of unusual interest. From either side of the capital extend finely drawn spirals. Such fine threadlike spirals could not have been carved from marble. It may be that the vase painter meant to delineate a bronze capital, or even, since bronze and marble were freely combined in both architecture and sculpture, a bronze embellishment of a marble capital. It is known that the Corinthian capital was derived from a metal original; on the Monument of Lysicrates in Athens, a marble knob on the capital is thought to stand for a metal rivet. So it may be that a type of capital otherwise lost is preserved for us in this lekythos.

These painted bottles must have been very gay when first they left the potter’s shop. Against their creamy ground the design is drawn in free unerring lines of soft color, brown in one ( page 79), red like the red of a chalk drawing in the other (page 76). Garments, hair, the sashes on the shafts are rendered in solid colors often of brightest hues. The girl on the latter vase has red hair and a gay red robe; the boy has brown hair bound with a red fillet and wears a robe of purplish brown with a white border on which are embroidered red dots. The sashes on the shaft are red. Such bright colors would have shown off beautifully when the vases stood in vivid Greek sunshine on the marble steps of grave monuments, their creamy ground set off from the glistening surface of the marble by the fine black glaze of the neck and base. Or they would have made a fine flash of color, in case, as the dealer stated of these two, they had been set on a marble sarcophagus in a tomb.

The scheme of color used for these lekythoi corresponds closely to that of the painted marble stew that have been recovered, and probably differs but little from that of the great wall-paintings. Aristophanes cast his jibes at the humble painter of funeral lekythoi; we are profoundly thankful to him not only for the intrinsic beauty of his works and the light he has thrown on funeral customs but for the hint he has given as to the beauties of grander works of art, now forever lost.

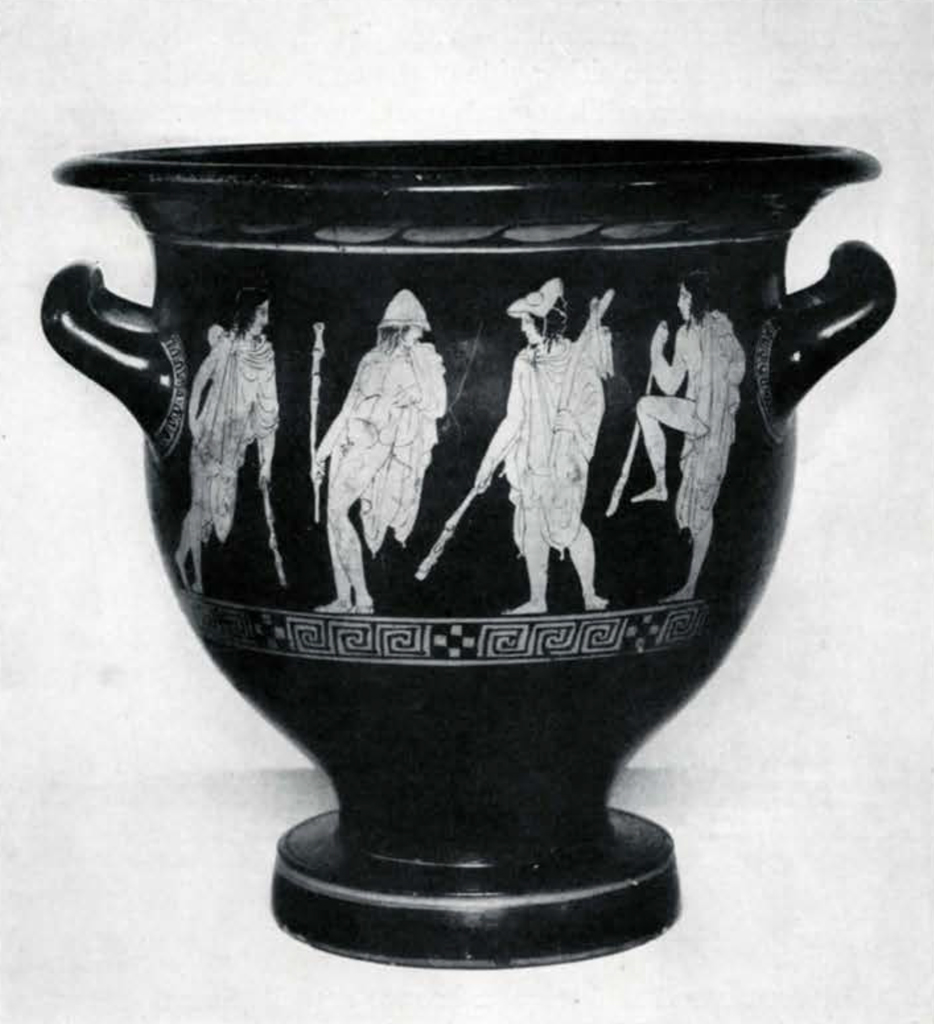

A Bell-krater by the Painter of the Berlin Deinos

This vase, page 82, is clearly to be identified with that shown in the Burlington Catalogue for 1903, and attributed by Mr. Beazley to the Painter of the Berlin Deinos. It was formerly in the Newton Robinson collection, but between the time it was loaned for the Burlington Exhibition and the time of its purchase by the Museum, it has suffered from too assiduous cleaning, for the delicate lines representing the rocks against which the hunters lean are hardly to be discerned at present, whereas they show quite plainly in the reproduction in the Burlington Catalogue.

The vase is a good example of the work done in a period some fifty years after that of the lekythos on page 74. The shape, a favorite one in this phase of vase-painting, was used for mixing wine and water. A wreath of leaves is painted just below the rim. A line of broken maeanders is carried far enough around the body to serve as a base for the figures. Four boyish hunters are represented on the obverse. Three of them seem to have paused for breath when the fourth comes walking in with the quarry, a hare, and tells how it was taken. Each boy is dressed in sporting country garb, wearing only a chlamys and a hat. The successful hunter wears a shade hat, or petasos, the other central figure a pilos. The hats of the others have fallen back on their shoulders. Each carries a knobbed stick, the λαγωβόλον, with which to fell his prey. On the obverse is the stock triad of draped figures.

It is a scene full of human interest; the artist is now concerned not only with the intricacies of bone and muscle in his figures, which he poses with freedom and with variety, but also in the workings of their minds. The picture might serve as an illustration for some country idyll. The rocks, now so largely gone, gave perspective to the scene and suggest the influence of frescoes.