THE archaeologist of a museum is presumed, above everything else, to be acquainted with all types of specimens and artefacts from his chosen field. His colleagues in universities and other similar institutions may largely ignore that field and confine themselves to the deciphering of hieroglyphs or to studies of language, history, religion or art, but the museum archaeologist can plan or plead no such restriction; his primary interest must ever be the objective, tangible phases of alien cultures, his aim the visualization of these cultures through the medium of their products.

Within reasonable bounds this popular presumption may not be unjustified; seldom is the archaeologist mystified. In a large museum with its full quota of specialists covering every region, it is most unusual when an object submitted for identification or for sale cannot at once, or with a little research in the library, be assigned its proper position as regards place and time. Quite often the decision of the expert is received with doubt or indignation, for it frequently becomes his unavoidable duty to inform the applicant that the old club, well authenticated in family tradition as having belonged to Pocahontas herself, is, notwithstanding, a typical but rather ordinary specimen from the Fiji Islands, that the pottery vessel, the only one ever dredged up from the depths of the lost Atlantis, is a fraud of a well-known Peruvian type or that the little Mexican pottery figurine, while genuine, is so common in large museums that, far from being worth fifty dollars, it would bring but a few cents in the market.

However, from time to time, objects turn up which the experts, singly or in conference, are unable to place. The possibility of fraud is first eliminated or at least considered, for dishonest makers of antiques are so capable today that instances are known of the deception of some of the best authorities in the world. If the specimen passes this test and presents all the earmarks of a genuine piece, it may then be considered unique and assigned to the region to which it appears to bear the closest relation. It may be a peculiar or rare object from a well-known culture or, less likely, a typical specimen from an unknown culture or civilization. For, although archaeology has advanced far in the last few decades and popular interest seems to be increasing, yet every now and then an expedition reveals a forgotten and lost civilization with artefacts of a type quite different from any hitherto known. There are several well-known cases in the history of archaeology where such unique objects remained in museums for years, their proveniences uncertain, their origins undetermined, until later explorations revealed the culture of which they were typical. One such case was that of the beautiful Nazca pottery of Peru, of which thousands of specimens now grace the exhibition halls of most of the world’s large museums. Before 1901 only five pieces of this exquisite ware were known, having been found twenty-five years earlier, but in that year Dr. Uhle discovered the rich cemeteries in Nazca Valley which have since yielded up their treasure to the art of the world.

Museum Object Number: NA9251

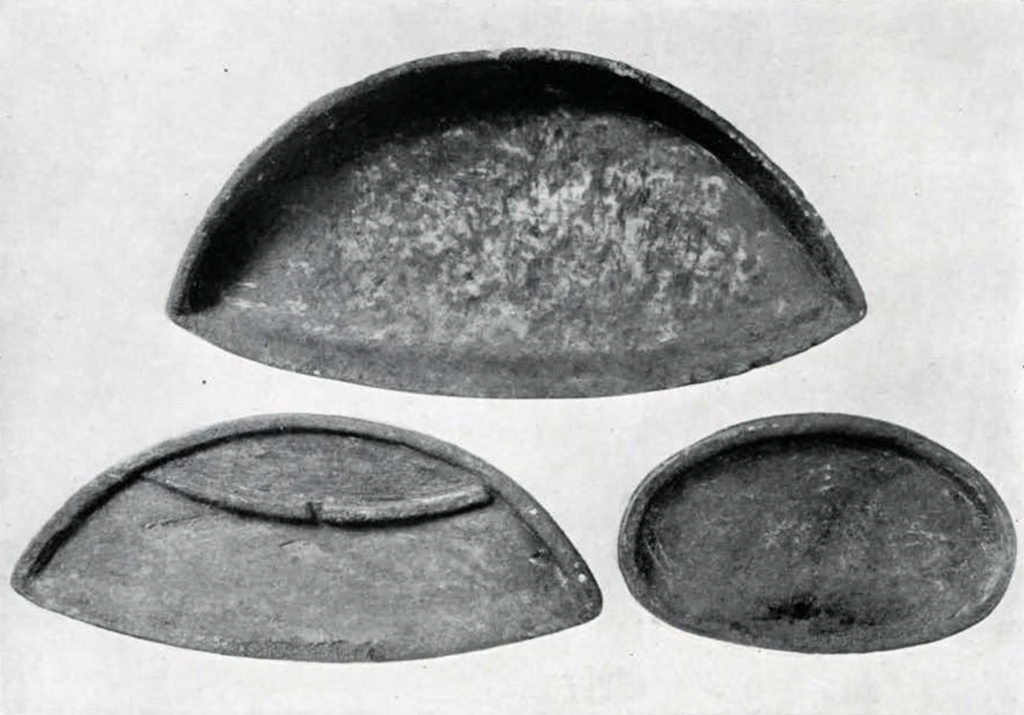

In 1921 the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM secured a specimen which never fails to attract the attention of every archeologist on account of its unusual character. Had it come to the MUSEUM without history or record of provenience, as is so often the case, and had it been absolutely unique, it is safe to say that its place of origin would never have been suspected by any authority on the region in question. Fortunately, however, the circumstances of its discovery were recorded, and further inquiries have elicited the fact that three similar objects have been discovered in recent years in the same general region, that of Cook Inlet, Alaska. One of these other specimens is in the possession of the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, in New York City, another in the Alaska Historical Museum at Juneau, Alaska, and the third in the possession of a trader in Alaska. Of these, the first three are so similar in size, shape and decoration that only by careful observation of details can one be distinguished from another. The specimen last mentioned is smaller and ruder.

The questions raised by the discovery of these peculiar specimens are naturally these: Are they modern frauds and forgeries made for sale or genuine native objects? Are they indigenous products of the place where they were found or were they brought from another region? By what people were they made and at what period? To what use were they put?

The possibility of the fraudulent counterfeiting of primitive manufactures is the first thought that occurs to the archaeologist upon consideration of an untypical specimen. The fact that, as in this case, a definite provenience is given does not entirely disarm suspicion, for instances are not unknown, especially in the case of the more sought-after antiques of the Old World, where forged specimens, so carefully made as almost to defy detection, have been buried for a considerable length of time and subsequently excavated. The specimens under consideration, however, bear all the earmarks of genuineness ; their condition reveals the wear of long use and the damage of frequent handling, and the carving shows none of the telltale sharp edges and striated lines which betray the use of modern steel tools.

The three similar specimens were found within a relatively restricted area, and it is not impossible that all came from the same village site or cemetery. Apparently the first one discovered was that now in the Juneau Museum which was turned up by Charles Ulanky on June 15, 1913, while plowing his field on Fish Creek, four miles above the settlement of Knik on Knik Arm at the upper end of Cook Inlet, Alaska. It lay at a depth of about one foot, and with it are said to have been associated skeletal remains, trinkets and a ” coin.” Only the bowl and the ” coin ” seem to have been preserved.1

The specimen now in the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, No. 4-9236, was discovered on the same Fish Creek but at a later time by Mr. Vaukey. The UNIVERSITY MUSEUM possesses a plaster reproduction of this specimen, N. A. 4985, an illustration of which is shown on page 179.

The specimen belonging to the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM, N. A. 9251, a general view of which is shown on page 172, was found by W. E. Johnson on September 16, 1919, on the southeastern part of the Kenai Peninsula near Seward, Alaska. Seward lies at a distance of about one hundred miles of travel from Knik, making them almost next-door neighbours in this land of immense distances.

The smaller and less typical specimen is at Kaltag on the Yukon River, about four hundred miles from its mouth but only seventy-five miles from the sea at Norton Sound. It is apparently therefore not of coastal origin though the owner believes it to be of Eskimo manufacture and originally brought from the coast. It was, according to reports, washed out of the bank of the Skageluk River during the spring ” break-up ” and deposited by the ice on the bar where it was found.

These unusual specimens may briefly be described in the following terms. Each has the shape of a massive oval bowl with thick bottom and sides and relatively shallow interior, in the medial line and in the posterior part of which is carved the upright head and bust of a human figure. An incised groove encircles each specimen just below the rim. No further details are at hand concerning the Kaltag specimen except that it is of inferior workmanship, is made of a reddish stone, and is unusually small, measuring eight inches long, six inches wide, three inches high and weighing about twelve pounds.

The three larger specimens have the following details in common. The interior floor and the rim are smoothed or polished, the rest carefully finished. The human figure is shown from the bust up, as if it were partially immersed or buried, and the forearms and large hands are portrayed in low relief on the floor of the vessel, stretched out towards the front. The position of the figure may be the same in the Kaltag specimen, although it is described as in a seated position. A straight, thin, shallow groove is incised in the floor of the bowl, in the medial line and running from just in front of the figure to near the lip at the front. Here at the point of the oval, the width of the rim is slightly lessened by a bevel or channeled groove on the inside.

On the rim, which is about an inch in width and slanting slightly downwards and outwards, are three groups each of three relief elements at the two sides and at the back. These nine elements are in the nature of short bands or ribbons in low relief and extend from the rim down the slope on the inside and a short distance across the floor of the bowl. Beneath each of these nine elements, on the convex exterior sides of the bowls, is another decorative element.

All three vessels are of rather massive size and weight, show evidences of considerable use and wear and are made of a fine vesicular volcanic tuff, variously described as gray, light gray, or greenish gray, but probably identical. The Philadelphia and New York specimens are of practically uniform size, that of the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM being sixteen inches long, fourteen inches wide and weighing forty-six pounds, the other half an inch larger in each dimension and weighing sixty-one pounds. The Juneau bowl is slightly smaller and measures twelve and a half inches by eleven inches. It weighs twenty-one pounds and stands five inches high, the floor being one and a half inches below the rim. The specimen in the Museum of the American Indian stands somewhat higher, five inches at the front and five and three-quarter inches at the back, the rim being therefore approximately level, while the rim of the specimen in the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM is noticeably sloping and the height less, the anterior height being only three and one quarter inches, while the posterior height is five inches. The depression of the interior floor is in each case two inches. The sides of the Philadelphia specimen are more convex, but the base flatter, while the sides of the New York bowl are more nearly vertical with the sides and base meeting at a rather sharp angle.

Museum Object Number: NA9251

Image Number: 12147

In point of decoration, however, it is the Juneau bowl which seems to bear the closer resemblance to the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM specimen. In both, the nine low-relief ornamental figures in three groups on the rim have zoömorphic forms representing heads and necks, the triangular heads resting on the rim, the long, slightly tapering necks extending down the surface of the interior of the bowl. As in the case of the human figure, they give the impression of heads protruding above the water, the bodies being submerged. Identification of the animals represented on the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM specimen is difficult, the form being too generalized, but the seal appears to be the most probable interpretation. Five main features are seen, slightly raised areas separated by slight depressions, two ears at the back, two eyes in the anterior portion, and a nose or snout at the point. Tiny incised dots represent the pupils of the eyes and the necks bear each two larger incised dots. Father Kashevaroff says of the Juneau bowl, “Flanking the image on either side and in the rear, in groups of three, are relief images having animal heads resembling the jackal or dog, with necks extending into the bowl and with human arms and legs on the outside.” The jackal, of course, is an inhabitant of eastern Europe, northern Africa and southern Asia and is not found in America, or Siberia. These rim elements are without any zoömorphic character on the New York specimen, although otherwise identical. It is probable that they have here become conventionalized.

The nature of the nine corresponding decorative elements on the outside of the bowls is even more doubtful. In the above quotation from Father Kashevaroff they are interpreted as “human arms and legs” belonging to the animal heads on the rim. No further description of them is given and the illustration shows merely the upper part of one of them; this, however, seems to resemble most closely the figures of the bowl in the Museum of the American Indian. The corresponding elements of the specimen in the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM as illustrated on page 176 bear some resemblance to very conventionalized headless human figures, although the writer must confess that no such identification occurred to him until after reading Father Kashevaroff’s article, and it is altogether likely that this interpretation is at fault and that the elements are purely decorative. The ” torsos ” and ” arms” are unduly short in proportion to the ” legs ; ” while the balls at the ends of the upper limbs may be considered as hands, no ” feet ” are portrayed on the lower limbs. The corresponding figures of the New York bowl lack entirely any anthropomorphic or zoömorphic character and are purely decorative. Their general resemblance to the elements of the Philadelphia bowl is, however, obvious. In each case the figure consists, in the main, of a pair of upper circular or curvilinear elements beneath which is an element of a branching, drooping nature. The pair of rings of the former specimen might be construed as conventionalizations of the already conventionalized “hands” of the latter one, but the four equal draped elements can hardly be derived from the two “legs” by any reasoning.

These three groups of decorative elements are connected by festoons in low relief, at least in the two bowls here illustrated, the description of the Juneau specimen making no mention of this feature. In this case also it is a question whether these elements represent conventionalized natural features; the writer believes this to illustrate the ease with which such false interpretations can be made. The two anterior festoons of the New York specimen, each consisting of a curved band in low relief with a medial longitudinal groove and an incised dot at either end, enclose between them, at the exact front of the bowl, three pendent elements carved in low relief which are obviously the analogues of the triple elements at sides and rear. In the centre, at the lowest point of each loop, the medial groove bifurcates to enclose a quasi-oval element in which is carved a horizontal groove with large central incised dot, the element thus much resembling an eye. These two anterior loops, taken with the central group of elements, at once suggest the con-ventionalized head of a beast with eyes and snout.

That this interpretation is probably a false one is indicated by the posterior half of this specimen where the festoons, singly in this case, connect the three groups of triple elements, revealing themselves as purely decorative and not as representing half of a face.

The connecting festoons of the Philadelphia specimen are obviously purely decorative and betray no zoömorphic character, but yet are perfectly analogous to those of the New York bowl. As in the latter case, they are four in number and connect the three main groups of decorations and the anterior point of the vessel. Each is made of a curving band in low relief with a medial groove and is broken in the middle by another element. In this case, however, the latter is composed of two concentric nuclear circles on which the sagging festoon rests, making of the latter, therefore, two loops instead of one.

It should be noted that in the case of the other design elements the naturalistic tendencies, such as they are, are found on the bowl belonging to the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM, the other showing no, or the very vaguest, traces of such ; this also would militate against a naturalistic interpretation of the front of the Knik specimen.

On the front of the Philadelphia specimen, between the ends of the two anterior festoons, is carved in very low relief and rather inferior technique a rude human face. In this respect it resembles the Juneau specimen, of which the description reads, “Beneath the lip and looking toward it is a human face in relief suggesting the sun or source of light.”

So much for the actual specimens. As regards their origin, since this is their first appearance in print except for Father Kashevaroff’s short article, experts have not yet reached a consensus. The opinions of those who have expressed them privately form an interesting study in psychology. One is reminded of the opinions expressed by the various hearers of the strange sounds in Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue. Here, it will be remembered, the local gendarme, speaking only French, believed the words to be Spanish, while the silversmith thought them Italian, a language he did not understand. The Spanish undertaker, however, was certain the accents were English, although he confessed to ignorance of that tongue, but the Italian confectioner inclined to identify them as Russian, although he was not familiar with the latter language. The English tailor, although admitting his ignorance of German, believed the words to have been in that idiom while the Dutch restaurateur who knew no French avowed his certainty that that tongue had been employed. Thus they agreed in nothing except that the words were of a nature different from anything with which each one was acquainted.

The case is very nearly as bad in the problem before us. While no scientist has yet carefully investigated the question and so, cautious individual that he is, has not expressed his judgment in print, yet privately expressed opinions and surmises seem very much like those of Poe’s deponents. Those persons most familiar with the Eskimo region almost unanimously deny that the stone bowls are from the modern or recent Eskimo, and many of them jump at the conclusion that they must be Chinese or Japanese, while the Orientalists as vigorously reject the possibility of Oriental origin and suggest Alaskan Indian, or some other American source.

The discovery of a “coin” together with the bowl now at Juneau would seem to afford a potent argument to the proponents of the Oriental theory. Unfortunately, although it is definitely stated by Father Kashevaroff that Mr. Ulanky found some skeletons, trinkets and the “coin” at the same time and place as the bowl, such secondhand evidence of association cannot be accepted before the court of science which demands careful expert excavation in order that apparent associations may be accepted as unequivocal and not fortuitous and accidental. The natures of the skeletons and trinkets are unknown ; had the skeletal remains been saved, the question might be settled by an expert physical anthropologist.

Were the “coin” really such, bearing date of mintage, head of reigning monarch or other unequivocal evidence of its age, it would afford some clue towards determining the age of the bowl. Unfortunately, it turns out to be of very uncertain date. It is, all authorities agree, undoubtedly Chinese, but an amulet rather than a coin, a talisman of Taoistic connections, expressing a prayer for good luck, long life and riches. Such objects differ little from century to century, due to the static conservatism of religion. So great is the range of possibility that while one expert informs us that a recent Chinese work on bronzes pictures this coin, or one practically identical with it, and states that it was made in the Chin dynasty, 265-420 A. D., another, after a more superficial examination, pronounces it about fifty years old. A third states that he secured a score of similar amulets recently in China. It is unlikely, thinks Miss Fernald, in charge of the Department of Far Eastern Art of the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM, that the amulet is older than the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and it may be more recent.

Were it certain that this medallion was interred together with the stone bowl, we should be justified in granting that some connection, at least, existed between the makers of the bowl and the Chinese. It would not of itself indicate that the bowl is of Chinese origin, or that the makers of it came from China or ever saw China or a Chinese. A small object of interesting nature frequently may be carried great distances in trade, passing through many different tribes to reach persons who never heard of the land of its origin. The “coin” may have been brought directly from China, however, in a junk. But even though the medal and the bowl were interred at the same time it would afford no clue as to the age of the latter, for coins of rather ancient date are still in circulation in China. Moreover, there is no way of determining the length of time required for the passage of the amulet from China to Alaska.

Image Number: 12146, 12150

Such certain association would, however, indicate some trade between the cultured Orient and America, a connection which, before the days of the first European discoverers, has not been accepted by scientists. For I think I am correct in saying that no relations have been proved to have existed between America and Asia, from the period of the great migrations which populated America until the time of Bering in 1741, except a little local intercourse with the Siberian tribes just across Bering Straits. Although it is extremely likely that, ever since the time when navigation was sufficiently perfected in the Orient to permit long sea voyages, about the beginning of the Christian Era, occasional boats have been driven from Japanese or Chinese seas to the Pacific Coast of North America, several well-authenticated instances having occurred in the last few centuries, yet we have no proof of such landfalls in aboriginal days.

But granting for the sake of the argument that the bowl and the coin were actually associated, two possibilities must be considered—either that both objects were brought or traded from China at the same time, or that the bowl was made elsewhere, the coin brought from China.

To some of the students of Eskimo life and art the reputed association of one of these unusual bowls with a Chinese coin is sufficient proof of the Chinese origin of the bowl itself. Thus Father Kashevaroff writes in his published account, ” The vessel is clearly not of Aleut, or Eskimo craft, as neither of these people have been known to produce any utensils resembling this. Doubtless it is of Asiatic origin and was brought to the Alaskan coast in prehistoric times.” He then recounts the story of the Japanese boat ” Ukamija Maru” which drifted from Japan to one of the Aleutian islands in 1793, and suggests that there may be some remote connection between it and the stone bowls. In a letter he further adds, “And now since I have acquired the Chinese coin dug out from the same place I am more than convinced that the lamp came from the Orient also.”

The Orientalists, however, are equally dogmatic in denying any suggestion of Oriental provenience. Miss Helen E. Fernald, Assistant Curator of the Section of Far Eastern Art of this MUSEUM, cannot see any Oriental traits in them, and Mr. H. U. Hall, Curator of the Section of General Ethnology, who spent more than a year among the aboriginal peoples of Siberia, states that they resemble nothing Siberian within his knowledge. Dr. B. Laufer, Curator of Anthropology at Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, whose knowledge of the civilization and history of China and the Orient is unexcelled, writes unequivocally, ” I have never seen anything like them. I may state positively that I can see nothing Japanese, Oriental or Asiatic in them. I would say that they are distinctly American.” He then suggests the possibility that they may be productions of the Tlingit or of other Alaskan Indians. To this suggestion Mr. Louis Shotridge, Assistant in the American Section of this MUSEUM, Tlingit born and reared, takes decided exception, stating that they resemble no form of Tlingit art known to him. In this protest he is seconded by Lieutenant Emmons. The suggestion has also been made that they are manufactures of the Aleut, that interesting and rather differentiated Eskimoid people who inhabit the string of Aleutian Islands extending across Bering Sea towards Siberia. This theory is ridiculed by Father Kashevaroff and Lieutenant Emmons who are familiar with the Aleut people.

The experts being thus at loggerheads, let us examine the case on its merits.

The art and archaeology of China, Japan and the Orient in general are far better known than those of Alaska. A group of vessels displaying a new type of form and art would be much less likely to appear from China or Japan than from Alaska, the archaeology of which is as yet hardly touched.

It is unthinkable that an ordinary fishing junk from the Japanese coast would carry with it three or four heavy ornate carved stone objects of an entirely unknown type. The objects which such a vessel would carry would be of the most common, utilitarian character. Neither is it credible that several such boats would each carry one such vessel of a type not before known, nor that, the ships having been wrecked on the coast, the bowls would have floated ashore to be later excavated. An overland journey from the Orient across Bering Straits would seem to be equally unlikely considering the weight of the specimens, one of them weighing upwards of sixty pounds, and the absence of wheeled vehicles, draught animals and roads. In view of these facts, and despite the discovery of the Chinese coin, it must be admitted that the importation of these bowls into Alaska from China or Japan is an untenable theory. Logically, also, it will be granted that such massive specimens are most likely to be encountered not far from their place of manufacture.

Examining the nature of these specimens closely, one observes first that they are made of volcanic tuff. Were the peculiarities of all the rocks of the world known and classified we might be able to settle the question of the provenience of these objects on this point alone, but tuff is too common a material. Suffice it to note, however, that the region of Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, is one of the most active volcanic districts in the world today; tuff and lava must be the main components of the land there.

The general form of these unique bowls is such that everyone who refers to them, whether he be proponent or opponent of the theory of their Oriental origin, speaks of them as “lamps.” The lamp, it should be noted at once, is probably the most characteristic feature of Eskimo culture. It is found among all the Eskimo groups from Labrador to Alaska, their very existence depending on it; conversely no other American primitive people possesses it. The part which the lamp plays in Eskimo life is of such importance that several deep studies have been made upon it, bringing out many vital and interesting points.2

The conclusions of Dr. Hough, the author of these studies, are of such interest and importance that I cannot forbear from quoting them verbatim: ” The conclusions reached are that the Eskimo, before he migrated from his pristine home, had the lamp, this utensil being a prerequisite to migration into high latitudes; that one of the most important functions of the lamp is for melting snow and ice for drinking water; that the lamp is employed for lighting, warming, cooking, melting snow, drying clothes and in the arts, thus combining in itself several functions which have been differentiated among civilized peoples; that the architecture of the house is related to the use of the lamp—the house is made non-conducting and low in order to utilize the heated air; that the lamp is a social factor, peculiarly the sign of the family unit, each head of the family (the woman) having her lamp; that the invention of the lamp took place on some seacoast, where fat of aquatic mammals of high fuel value was abundant, rather than in the interior, where the fat of land animals is of low fuel value; that the typical form of the lamps arises from an attempt to devise a vessel with a straight wick edge combined with a reservoir, giving the vessel an obovate or ellipsoidal shape.

“Finally, from observation of lamps from numerous localities around the Eskimo shore-line, it is concluded that lamps in low latitudes below the circle of illumination are less specialized than those of higher latitudes. For instance, the lamps of southern Alaska have a wick edge of two inches, while those of Point Barrow and northern Greenland have a wick edge of from 17 to 36 inches in width. It becomes possible, then, to say with some certainty the degree of north latitude to which a lamp appertains, light and temperature being modifying causes. Driftwood, the fuel supply, and the presence or absence of materials from which to construct the lamp must also be considered.” The specialization of the lamps from higher latitudes of which Dr. Hough speaks refers, naturally, to their utilitarian purpose, not to their artistic or technical perfection.

The Eskimo lamp may be universally described as a shallow bowl containing oil from melted blubber or other fat from sea mammals, in which rests a wick of moss.

The part of Dr. Hough’s study which most concerns the present problem is that on the distribution of the various types of Eskimo lamp. As has been briefly stated or suggested in the above resume, the greater coldness and darkness of the Arctic regions, combined with their lack of wood, necessitate a large lamp with a long wick edge. The typical lamp of this region, therefore, is semicircular or semiovoid with a long, straight wick edge. They are made, almost universally, of steatite or soapstone, to secure which the Eskimo sometimes make very long journeys. Three of these more typical Eskimo lamps from the Arctic coast in the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM are illustrated on page 182. The largest, N. A. 3135, is from Repulse Bay, far to the east; the smaller, N. A. 10246, is from Point Hope, Alaska; the oval lamp, N. A. 6904 is from Point Barrow, Alaska.

South of Bering Strait the moderating influence of the Japanese Current, the greater amount of forested region and the relative shortness of the Arctic winter night all combine to diminish the vital importance of the lamp which, therefore, differs considerably here from the norm of the more boreal regions. Some of the lamps from Norton Sound, just south of Bering Strait, are ovate or sub-triangular and made of tufaceous stone. On the great stretch of coast between here and the Alaskan Peninsula, the tundra of the deltas of the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers, the lamps are round saucers made of a poor grade of pottery, radically different in every respect from those of the Arctic coast.

The lamps of the region of Cook Inlet, the source of our strange bowls, are naturally those of maximum interest to us. This is close to the southern limit of Eskimo territory and the region where the need for the typical, purely utilitarian lamp is least. Several quotations from Dr. Hough’s monographs will show the general type of the lamp in this region. ” They become oval and of stone in the metamorphic and igneous country to the southeast and southwest through the Alaskan Peninsula and Aleutian Chain. At Bristol Bay, the lamps are oval or sadiron-shaped, finely worked from hard stone. Though some of the lamps are large and heavy, the wick edge is narrow. The southern Eskimo of Alaska, notably at Kadiak Island and the Peninsula, made their lamps of very hard dioritic rock.”

Museum Object Numbers: NA10246 / NA6904A / NA6904B

Image Number: 12148b, 12148c

It is on Kodiak or Kadiak Island, the large island just south of the base of the Alaskan Peninsula and just west of Kenai Peninsula, on the small island Afognak just east of Kodiak and between it and Kenai Peninsula, and on the neighbouring portions of the Alaskan Peninsula that the lamps most resembling ours from Cook Inlet and Kenai Peninsula are found. Of these Dr. Hough says, “They are of hard dioritic rock and are unusually carefully worked and finished. It would be difficult to mention better specimens of stone working. Some of the lamps are very large, one in the collection (of the National Museum) weighing 67 pounds. They are oval in outline, with a shallow reservoir, low walls with flat top, the sides are often grooved, the bottom convex. The wick edge is a small groove cut through the wall at the apex of the oval leading to it.” This description would be applicable to any of the fine Cook Inlet lamps, disregarding their unique ornamentation.

Two of the lamps from this region, belonging to the United States National Museum in Washington, are reproduced on page 187. The upper specimen, No. 90473, from Afognak Island, is smaller than the Cook Inlet lamps, measuring roughly eight by ten inches in size and three inches in height and weighing eleven pounds. It is made of a fine-grained, gray basaltic rock. No data are available on the lower specimen, No. 90477, from Kodiak Island, Alaska, but its general resemblance to the Cook Inlet lamps is obvious.

Nine lamps from the region of Kodiak Island are mentioned by Dr. Hough, most of them, however, being quite small, four of them not above six inches in length, while the largest is less than twelve inches in length, considerably smaller than our three massive bowls. The largest of these specimens, unfortunately not figured, is described in the following words: ” Very finely worked from green metamorphic stone; ovate in outline, with squared edges and rounded bottom, on which the lamp accurately balances. Reservoir deep, uniformly concave; upper edge flat; lip narrow, cut in the edge at the point of the oval. The edges and reservoir have been polished; the bottom shows marks of hammer stone in working the lamp out. This is a splendid specimen of stone working. Length, 11 inches; width, 10 inches; height, 4 inches. Eskimo of Afognak Island, Alaska.” Another of the large lamps is ” of greenish-gray rock, finely worked and polished. It is oval in shape, broader at the back than at the front, with almost flat, slightly rounded bottom, upon which it firmly rests. . . . The side, edge, and reservoir are polished. Katmai, Shelikoff Strait, Alaskan Peninsula.”

Almost every point of these descriptions would apply equally well to the lamps under consideration. The beautiful lamp from Afognak Island is the most peripheral of those described by Dr. Hough; it is also apparently the finest. Drawing the logical deduction from these facts, one should expect to find even finer types of lamps farther along the coast. One hundred and seventy-five miles farther as the crow flies is Seward and seventy-five miles farther yet Knik. Another one hundred and seventy-five miles from either Seward or Knik brings one to Copper River, the limit of Eskimo territory. These are short distances to the Eskimo and to Alaska.

Reason and comparative studies have therefore led us unavoidably to the conclusion that these remarkable and puzzling objects are stone lamps, made by the Eskimo in approximately the region in which they were found. The evidence has been fairly convincing and we may be reasonably confident that the conclusion is a correct one.

The three larger lamps, so similar in every respect, must have been made at approximately the same time and place, possibly even by the same person. They must have served a similar purpose and, from their finished character, it may be surmised that they had some religious ceremonial purpose which required their embellishment to a point not desirable in lamps of purely utilitarian office. We should be cautious about accepting the natural interpretation that the human figure represents a deity, before whom burns an eternal, votive flame. Such a religious concept is entirely foreign to the religious psychology of primitive American peoples. It is, however, one of the most fundamental elements of religious observance among the higher civilizations of the Old World. This may be a significant point as indicating influence from Asia, but for the present we will regard the figure as purely decorative.

The wick of the lamp was doubtless a small one, placed in the point of the oval. Whether the groove in the medial line of the floor of the vessel served to direct and steady the wick, or served as a channel through which the oil might flow from the melted blubber, or for some other purpose, is uncertain.

Several other interesting phases of the question still remain, and we shall find the evidence on these less conclusive, and the results less certain, than the previous conclusions. These are: Whence came the example, the urge and the artistic influence which impelled their makers to produce these remarkable works of art? What group of Eskimo produced them? At what period were they made?

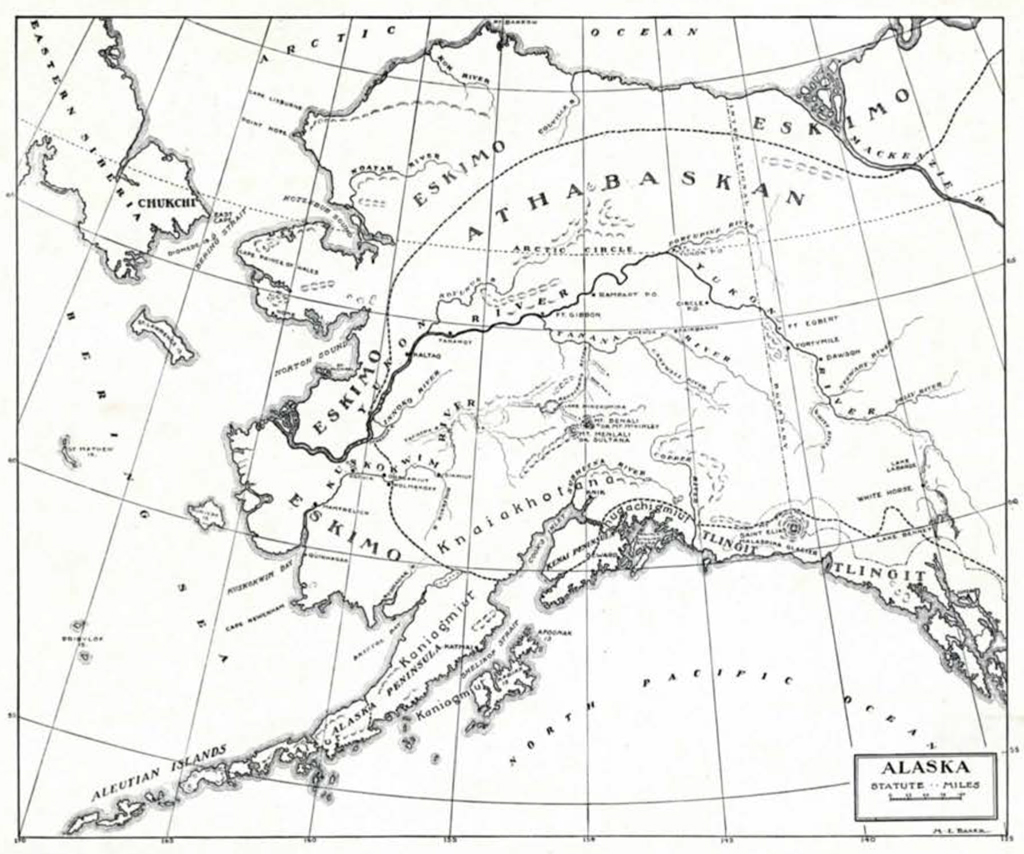

Strangely enough, the region of Knik is today, and apparently has been since earliest reports, inhabited not by the Eskimo but by the Knaiakhotana, one of the many tribes of the great Athabaskan linguistic stock of American Indians who occupy the great western interior of Canada, being everywhere, except in this one spot, cut off from the sea by the litoral Eskimo. The Knaiakhotana occupy both sides of Cook Inlet as far down as Chinitna Bay on the north side and Kachemak Bay on the south side, and about half of Kenai Peninsula, the seaward portion being inhabited by the Eskimo. The town of Seward is near the boundary of the two. These Eskimo belong to the Chugachigmiut tribe whose lands reach from the western end of Kenai Peninsula to the Copper River, the Tlingit Indian frontier. West of them are the Kaniagmiut, the largest and most powerful tribe of Eskimo on the Alaskan coast, who inhabit Kodiak Island and the adjacent mainland from Ugashik River on the Alaskan Peninsula, the frontier separating them from the Aleut of the Aleutian Islands, to Iliamna Lake which separates them from the Athabaskan Knaiakhotana mentioned above.

It is most unlikely that the Knaiakhotana or any other Athabaskan people of the interior could have made these lamps. Although this tribe is said to possess a higher grade of culture than other interior Athabaskan groups, probably through Eskimo influence, yet their culture is considerably below that of the latter. Both art and invention are at a very low stage among the Indian tribes of the interior who possess no lamps, except those of civilized manufacture. They may be left out of the picture; either the region of Knik was originally Eskimo territory or else the lamps were brought a few miles from Eskimo settlements on the coast.

While available historical records indicate no change in the habitats of the peoples of this region, yet since it is only in this section that the Athabaskan peoples supplant the Eskimo on the coast, we may with some confidence believe that this displacement occurred in relatively recent years, and that at the time of the manufacture of these bowls, Knik lay in Eskimo territory. We may also posit the theory that the inhabitants at that time, and consequently the makers of the vessels, were the Kaniagmiut, since they are credited with being unusually good artisans and the manufacturers of the similar though plain lamps from Kodiak and Afognak Islands. They are apparently rather closely related to the Aleut who are also good artists and made similar, though less perfect lamps. In this connection it is of interest to add that, according to Mr. Shotridge, the peoples who came into contact with the Tlingit at their northern frontier were Aleut, not Eskimo.

The peculiar, highly developed and somewhat conventionalized art of these specimens is their most interesting and characteristic feature; except for this they would be hardly distinguishable from lamps from the neighbourhood of Kodiak Island. The nature and origin of this art constitute our greatest problem.

Among anthropologists the theory, almost tantamount to an axiom, is held that in any culture area the highest development in culture will be found in the centre, the typical cultural elements diminishing in number, strength and complexity towards the periphery. When this is found not to be the case, external influence from other cultures is generally suspected. We should thus expect to find the highest development among the Eskimo in the central Arctic region. This may be true in certain or most respects, but is totally incorrect as regards the art. Eskimo art is poorly developed except in Alaska where it attains a high degree of excellence. Furthermore it improves towards the south as the limits of the Eskimo habitat are reached, and attains its maximum perfection in the region of Bristol Bay and the Alaskan Peninsula, in the general neighbourhood of our stone lamps.3 This unusual high development in a peripheral region can be accounted for solely on grounds of external influence.

The neighbouring foreign peoples with whom the Eskimo could have come into contact are few, the Chukchi of Siberia, the Athabaskan Indians of the interior, the Tlingit Indians of the coast to the south, and the Russians of the last two centuries. The Aleut of the Aleutian Islands to the west might also be mentioned, but these are related to the Eskimo and differ but slightly from them in culture.

The Athabaskans and the Chukchi may be eliminated from consideration; the former have practically no art, and that of the latter is no higher than, and quite similar to, that of the present Eskimo. Moreover, Chukchi influence would be felt in greatest degree at Bering Strait, whereas the zenith of Eskimo art seems to have been achieved further south. The honour seems thus to lie between the Tlingit and the Russians.

An analysis of the decorative elements of the stone bowls leads us nowhere. A few of them bear close resemblance to modern Eskimo carving, especially that on ivory, but the others resemble nothing in modern Eskimo, Tlingit, Russian or any other art which can have any connection. The groups of three animal heads carved on the rims of the bowls are especially Eskimoid, similar groups of heads of almost identical shape and probably representing seals being frequently seen on modern Eskimo carvings. One such in the possession of the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM, from East Cape, Siberia, N. A. 6491, bears four similar heads, and a bag-handle in the National Museum at Washington, from the lower Yukon,4 is decorated with eight such heads. The human figures rising from the floors of the bowls are rather rude and unstylized, but they somewhat resemble Eskimo human figures carved of ivory. The nuclear or concentric circle, such as is found on the exterior of the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM specimen, is probably the most typical of all Eskimo art motives. But the nine decorative elements on the exteriors of the bowls, in three groups of three, are apparently as foreign to Eskimo art as to every other art which the writer has examined.

Unfortunately the archeology of the Arctic regions is but slightly known, owing, naturally, to their inaccessibility and the difficulty of working there. Were this well known, the place of these lamps in Eskimo history and culture might probably be fixed. Such as is known throws little light on the problem. When W. J. Hoffman wrote his monograph on ” The Graphic Art of the Eskimo ” in 1897 he stated that examples of engraved and carved art were unknown in graves of pre-Russian period and this, together with the facts that the art improves towards the Alaskan Peninsula, the region which has longest been under Russian influence, and that the earliest Russian accounts of this region, while full and concise on most topics, contain no references to artistic carving and engraving, today one of the most striking features of Eskimo culture in Alaska, led him to conclude that the Eskimo art of Alaska is the result of Russian influence and therefore quite recent.

Did this conclusion still hold, we might with reason ascribe the strange art of these lamps to Russian influence. The region of Cook Inlet was one of the first centres of the Russians in America, a settlement having been made at Knik in 1792, but the Aleutian Islands, the Alaskan Peninsula and Kodiak and the other coastal islands, by which route the Russians traveled from Asia, were probably occupied several decades earlier. This theory would also explain the presence of the Chinese amulet as having been picked up in central Siberia by one of the earlier Russian traders and explorers and carried by him to Alaska.

Unfortunately for this argument, if the advance of scientific truth can ever be considered unfortunate, recent investigations contradict Hoffman’s strongest point. Dr. Diamond Jenness, Chief of the Division of Anthropology of the National Museum of Canada, writes: “Hoffman is certainly wrong in stating that there was no ivory or stone engraving or relief work among the Eskimo in pre-Russian times. As a matter of fact, the old pre-Russian art is the best, at least in the western Arctic; . . . I am suggesting that there was a very ancient Eskimo culture along the shores of Behring Sea, marked by a peculiar and very highly developed art that delighted in scroll work and geometrical patterns; and I believe that this culture goes back at least a thousand years, probably more. It seems to have affinities with the West Coast culture on the one side and northeast Asiatic on the other.” An examination of the objective products of this old Bering Sea Eskimo culture, however, reveals nothing in common with our stone lamps; the specimens are mainly of carved ivory and, while the design elements have a vague basic resemblance, no definite connection can be seen.

Turning as a last resort to the Indians of the Alaskan coast, especially the Tlingit, we find here the highest development in stone-carving of any aboriginal nation of America north of Mexico. Could we find any resemblance between the exceedingly characteristic, stylized and conventionalized art of the Tlingit and that of the stone lamps, the problem might be considered solved. However, we cannot even be sure of the point that is apparently most certain. Since stone-carving is highly developed among the Tlingit but uncharacteristic of the Eskimo, it would seem obvious that such a high development of sculpture as is shown by these lamps from the limit of the Eskimo region where it abuts upon that of the Tlingit must be due to the influence of the latter. However, according to Mr. Shotridge, the Tlingit had little contact with the Eskimo. Moreover, their traditions, to which anthropological evidence lends some support, relate that the Tlingit migrated to Alaska from British Columbia south of Port Simpson but a few centuries ago, displacing the Athabaskan tribes who then occupied their present habitat. The great Malaspina and Bering glaciers, descending from the St. Elias range, form an almost impassable and unavoidable barrier for a hundred and fifty miles along the coast, one that was seldom passed.5 Whether this migration legend is well founded, and if so, whether the Athabaskan tribes which the Tlingit displaced also practised the art of stone-carving, must await the decision of future archaeologists.

So far have our researches taken us, and they can take us no further until the spade of the archaeologist shall have revealed more of the early history of Alaska. While the hypothesis of Russian influence upon the Cook Inlet Eskimo, thus implying relatively recent date for the lamps and explaining the occurrence of the Chinese amulet with one of them, is not eliminated, yet it is more likely that the stone lamps represent the interplay between the art of the old Eskimo culture of Bering Strait of a millennium ago and that of the sculpture of the southern Alaskan coast in the region now occupied by the Tlingit. The art of the lamps shows some distant resemblance to both. The occurrence of the Chinese amulet we may ignore, although it introduces a disturbing factor. Such amulets are said to be frequently encountered in Alaska, and until one is found under unequivocal conditions which can be accepted by science, the alleged association of one with an archaeological object cannot be permitted to invalidate conclusions reached upon more certain grounds.

With this cautiously advanced identification, then, our researches must end. If they have not succeeded, for want of sufficient evidence, in solving the mystery of the makers of these remarkable stone lamps, they have at least cleared the air of the haze of unscientific guesswork which obscured the question, and have afforded a demonstration of the problems which face the archaeologist of a museum and of his methods of attacking them.

1 See An Oriental Stone Lamp, on pages 30 to 32 of Descriptive Booklet of the Alaska Historical Museum, Juneau, Alaska, 1922. Edited by Rev. A. P. Kashevaroff, Curator. While the final proof for this article was being read, a revised edition of this was received. The article is reprinted in unchanged form on pages 26 to 28 with the addition of two illustrations of ” The Chinese Talis-man,” obverse and reverse, and two paragraphs of text upon it.↪

2 The Lamp of the Eskimo, by Dr. Walter Hough, in the Report of the United Suites National Museum for 1896, pages 1025-1056, with twenty-four plates. The Origin and Range of the Eskimo Lamp, by Dr. Walter Hough in the American Anthropologist for April, 1898, pages 116-122.↪

3 “That the general results in graphic portrayals are more artistic among the natives of Bristol Bay and Norton Sound, and improve in delicacy of engraving toward the southward even to and including the Aleutian Islands.” W. J. Hoffman, p. 804 of The Graphic Art of the Eskimos, in the Report of the U. S. National Museum for 1895, Washington, 1897. See also pages 252, 253 of The Museum Journal for September, 1927.↪

4 Hoffman, op. cit., plate 26, No. 2.↪

5 See Ghost of Courageous Adventurer, by Louis Shotridge, in THE MUSEUM JOURNAL for March, 1920, pages 10-26.↪