ORIENTAL cults were always familiar with the figure of the nude woman, the “funeral Venus,” whose images are found in all the cemeteries of the old world. Local worship does not always explain its origin and character. Most of these images are clay figurines. The small collection of stone statuettes and carvings in bone which is dealt with here is treated separately because it is made of different material, and because it belongs to a late Graaco-Parthian period. Most of the figurines were discovered in tombs at Jumjuma, a small village near the ruins of Babylon. Like the terra-cottas, they have a funerary purpose, and they disclose a marked predilection for the nude female figure. Clay figurines always had a close connection with religion, and entire nudity always has a mythological meaning. Their common character is the place they occupy in funeral rites, and the symbolical expression they give to coarse but positive ideas on future life.

The nude love-goddess was a dominant and popular figure in Babylonia long before Praxiteles introduced the nude Venus to the assembled Greeks. The nude mother-goddess, holding and suckling an infant, is a familiar type in the old Sumero-Babylonian religion, under different names—Innina, Nana, Ishtar, Bêlit, Zarpanit, or Allat. But it is hard to decide whether these little figurines found in cemeteries have a close connection with the local cult, or—which is more likely—whether they have a larger significance in relation to the religious and funerary concepts of the whole country; whether the local idol is the glorification of the ancient nude female figure, or the latter a copy of an idol.

In any case they embody the idea, transmitted to us by Herodotus, of Mylitta the Assyrian Aphrodite, the goddess of sacred prostitution in Babylon, of Anaitis or Anat, the protective deity of Warka. Her cult was adopted by the Persians, especially by Artaxerxes II Mnemon, who ordained the erection of her statues through out the empire. The Greeks in their turn received her as Aphrodite or Artemis, not unlike the many breasted Diana of Ephesus. Susa in Elam had her oriental Diana called Nannaia in the Greek text of the Bible and Anahata in a local Persian inscription. Berosus mentions Susa as one of the cities in which Artaxerxes ordered the erection of a statue of Anaïtis.

There is a marked advance in the form and inspiration of these little nude figurines, which is due to the influence of Greek art and mythology after Alexander, but there is no complete transformation, no deep alteration in the cult and rites. The ancient local taste survives in the choice of symbols, dresses, and a deep note of sensuality.

The best book on the subject is still the catalogue of Figures Antiques de terre cuite du Musée du Louvre, by L. Heuzey, from whom we borrow many of the following notes. The Greek influence in Babylonia was attenuated by its fusion with older oriental elements. For clay figurines the Greek artists substituted alabaster, which is more refined, with a touch of affected elegance, while the clay figurines are coarser and their makers more preoccupied with symbolism in the first place. The Greek influence continued under the rule of the Parthian kings. The river Euphrates was the real frontier between the Roman and the Persian empires.

While Babylonia did not remain for even a century under Greek domination, history accounts very well for this partial but persistent intrusion of Western elements in the East, and the remarkable vitality of the cultural centres founded by invading Hellenism before and after Alexander. When the Roman power was at its highest, on the extreme border of the Roman province of Asia, Samosate on the Euphrates, the native city of the Atticist Lucian, had sculptors who kept the best traditions of Greek art alive on the frontiers of the Parthian country. Palmyra, late in the third century A.D., welcomed both Greek and Aramaean civilization.. Under the Parthian kings, the great city of Seleucia on the Tigris, heir to the destroyed city of Babylon, rich and prosperous with over six hundred thousand inhabitants, always preserved its autonomy. For the younger Pliny, it was still a Greek city with a Macedonian constitution, libera hodie, ac sui juris, Macedonumque moris.

In order to avoid direct contact between the Parthian troops and the large Greek population, the Parthian kings had established their court at Ctesiphon on the other bank of the Tigris. Far from being opposed to Greek culture, they took great care of the numerous Greek or Levantine communities imbued with Greek spirit in their empire. On their coins they bear the title Philhellene. The kings of Characene who in the days of Augustus ruled over lower Mesopotamia down to the Persian Gulf, stamped their names in Greek characters on their coins, and in Greek and Aramaic on one of their bricks preserved in this MUSEUM.

According to a report of P. Delaporte, in 1863, of excavations at Hillah near Babylon, a vaulted sepulchral room was found, including six tombs disposed in parallel order. The bricks employed in the construction bore the stamp of Nebuchadnezzar, showing that the vault was posterior to the destruction of Babylon. Masks, clay cones, and statuettes were discovered within. Each tomb had a statuette placed near the head of each corpse, except in the first tomb, that of a man. These were alabaster figurines corresponding to a class of Graeco-Babylonian clay figurines, of which they are perfected and richer copies. The relation between the funerary masks and the figure, age, and sex of the deceased is very doubtful, but they all seem to have been of local manufacture and to have had a funerary purpose, in which they confirm the conclusion of Loftus and Layard.

Museum Object Number: B9365

Image Number: 8038

Loftus’s Travels and Researches in Chaldea and Susiana though over half a century old, is still one of the classics of Babylonian archaeology, and his description of the burials at Warka in Graeco-Parthian times is worthy of careful reading, pp. 210, ff.

“Many small objects are associated with the—slipper shaped—coffins, either in the inside or around them in the earth or vault. The personal relics of the deceased consist of gold and silver finger-rings; armlets, bangles and toe-rings of silver, brass and copper; bead-necklaces and small cylinders. Gold ornaments are not uncommon, such as ear-rings, and small plates or beads for fillets, of tasteful and elegant design. Thin gold leaf sometimes appears to have covered the face like a veil; and one or two broad ribbons of thin gold not infrequently occur on each side of the head. Large pointed head-dresses, Budda—one of the workmen—told me, had been found and sold to the perambulating Jews who visit the Madan periodically for the purpose of purchasing the gold.

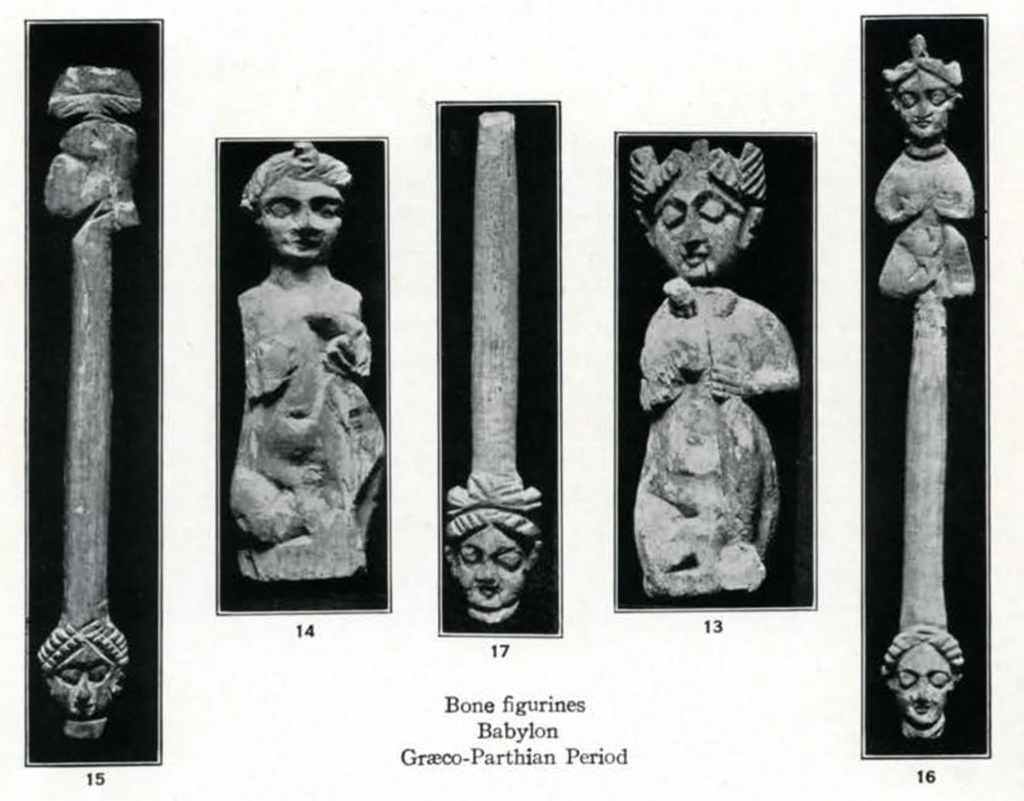

“With the above are articles of a different description such as small earthen drinking vessels and lamps, glass lachrymatories, copper bowls, hideous bone figures, probably dolls, and a variety of others.

“The top of the coffin is often a receptacle for small relics—apparently the parting gifts of friends—as the following list will show:—seven different forms of fragile coloured glass bottles, two curiously formed yellow glass dishes, a glass terracotta lamp (a constant accompaniment), four bone stilettos, two iron implements, the bones of a small bird, fragments of a bunch of flowers, and an ornamental reed basket (the plaits of the reeds being quite distinct) containing two pieces of khol or black paint for the eyelids, and a tassel bead. Judging from their character, these articles appear to have been the property of a female.

“Strewed in the earth around the coffins are numerous copper coins, the only articles which afford any positive clue to their age. . . The types are extremely indistinct, but no doubt is entertained of their being Parthian. Close to the foot of each coffin are one or more large glazed water-jugs and earthen drinking cups, of extremely artistic form. One . . . tall jug was found in a recess built for its reception in the side wall of the vault, within arm’s length of the coffin. The bones of a fowl with a flint and steel were also frequently deposited upon the lid. The practice of placing food and water near the body was certainly connected with the superstitions of the period. The same practice is, I believe, continued among the Arabs, who conceive that these articles are necessary to give the spirit strength on its long journey.

“Some of the most interesting objects found in the same position are small terra-cotta figurines, which were probably household divinities. Many are undoubtedly Parthian; such, for instance, as the reclining warrior, with a cup (?) in his left hand, wearing a coat of mail or a padded tunic reaching to the knees and a helmet ornamented in front. The whole costume is well represented on many coins of the Parthian epoch.

Museum Object Number: B318

Image Number: 8015-8017

“Several are female figures in loose attire exhibiting strange headdresses, which, doubtless, give us some notion of the costume of the period. One of these is very remarkable; it rises into two tall conical peaks, from which depends a veil, reminding one strongly of the English ladies’ costume in the time of Henry IV. Nude female figures, probably representing the Mylitta or Venus of the Assyrians, were extremely common at the Parthian period, having been handed down from antiquity. Similar figures are universal throughout the East before the Christian era. A few figures bear traces of colour.”

Some clay heads “are most interesting. They are infinitely superior to the rest in point of design and execution and mark the rapidly spreading influence of Greek art. They possess all the characteristic features and boldness of the Greek face and yet they can scarcely be other than the works of Babylonian artists. The hair is arranged in long ringlets and the heads are surmounted by lofty headdresses of different form.

“It would be endless to give in detail all the small articles which were discovered in connection with the slipper coffins.”

Clay, bone, or alabaster dolls were found in tombs of Hillah. They are nude figurines, with legs close together, and no base to stand upon. Their shoulders are bored through to attach a mobile arm. The use of dolls or articulated figures has a complex signification both religious and magic, as being an imitation of life. The same observation applies to all clay figures and to images in general.

Museum Object Number: B6180A / B14386

Some alabaster dolls have a hieratic attitude. Their right arm is bent forward, the hand open, as if ready to receive the offering. The prettiest were covered with gold ornaments, and had semiprecious stones inlaid in the eye sockets and navel, to add life and colour to their voluptuous nudity. Clay dolls have only masses of hair confined by a turban adorned with studs. They are a cheap reproduction of the better models, but their symbolism is the same. Nearly all show traces of a stucco coating in imitation of alabaster. On the white slip details were worked out with the point, and saliences of the body were accentuated in pink, marking the ribs, the folds of flesh, the sex, and the division of the legs. Several dolls with fixed arms copy the traditional attitude of the antique Venus, arranging the hair with one hand, and covering the breast with the other..

Funerary dolls are the direct descendants of the older Persian and Babylonian nude figures of Anaitis, Ishtar, Innina, or other forms of the goddess of love. She was long popular with the Parthian, and is still reproduced as the “celestial goddess” on the coins of Musa, the mother of Phraates, in the first century.

Other figurines found at Hillah show women lying on a couch, resting on an elbow in the attitude of the guest at a banquet. They wear a high peaked cap, not unlike the Phrygian cap adopted by Greek art as the proper headdress of mythological beings, especially of those from Eastern regions. The cap in the alabaster figures is sometimes gilded, or the hair is uncovered and tied on the top of the head in a bow after the fashion of Venus and other young goddesses of the Western Olympus. Some figures are entirely nude, or draped only about the lower limbs with a tight-fitting shawl, as is common in the Greek representations of Venus. They usually lean on a cushion, and the bed with its four legs is sometimes represented in terracotta reliefs. The figure of the deceased dressed in his best garments and resting on a couch like a guest at an eternal banquet is familiar throughout antiquity. The gods also were treated to sacred banquets and their statues placed on ceremonial beds on solemn festival days. On the top of the stage tower of Babylon, there was an empty shrine containing only a table and a magnificent bed on which the god Marduk was supposed to take his rest at night while visiting the high priestess.

Museum Object Numbers: B8997 / B9026 / B5984A

We may therefore consider these nude alabaster figures which in the late period were placed near the head of the dead as so many funeral goddesses, one a love goddess, the other a mother goddess, according to an ancient Babylonian tradition modified by Greek custom, which through a mythological interpretation saw the spirit of the dead absorbed into their divinity.

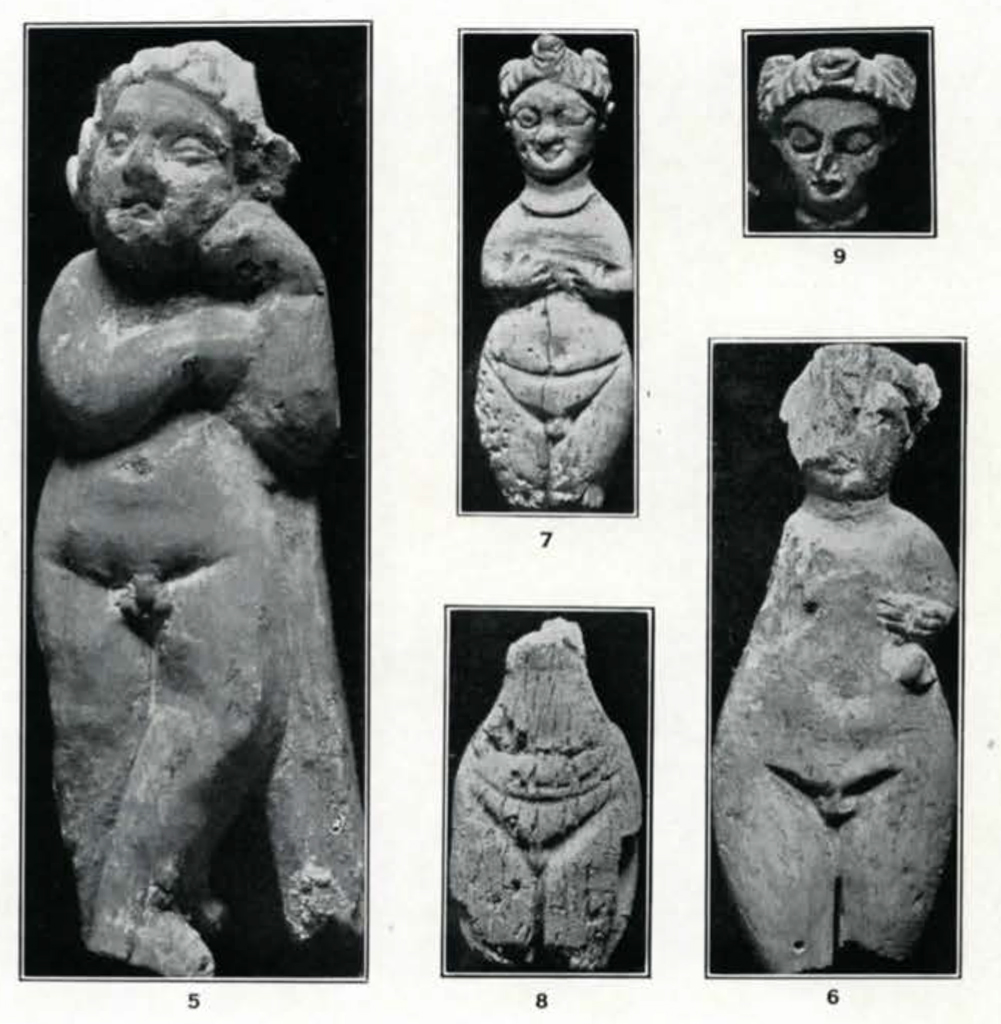

The same must be said of alabaster children’s figures found in tombs at Hillah. A nude boy is represented sitting on a small bench, his left leg folded under him. A stucco headdress is added, having two golden bullae like the berries on the ivy crown of Bacchus. He grasps with both hands a pine cone or a grape at which a bird is pecking, or which a snake tries to bite. He may have wings like Eros, and his headdress has three points or rays, which may represent curls of hair, or through a fusion of symbols in a late period may combine a peaked cap with ivy leaves. Sometimes it is only a hollow bust with a loose clay ball inside, both a funerary amulet and a rattle.

The connection of the child with folded legs with the images of the young Horus in Egypt and with the other infant gods like Bacchus, Athys, Adonis, was established long ago. In Carthage he holds in his hands the dove of love. In Babylon he was Tammuz, the newly born god of love, whom Ishtar brings back from Hades.

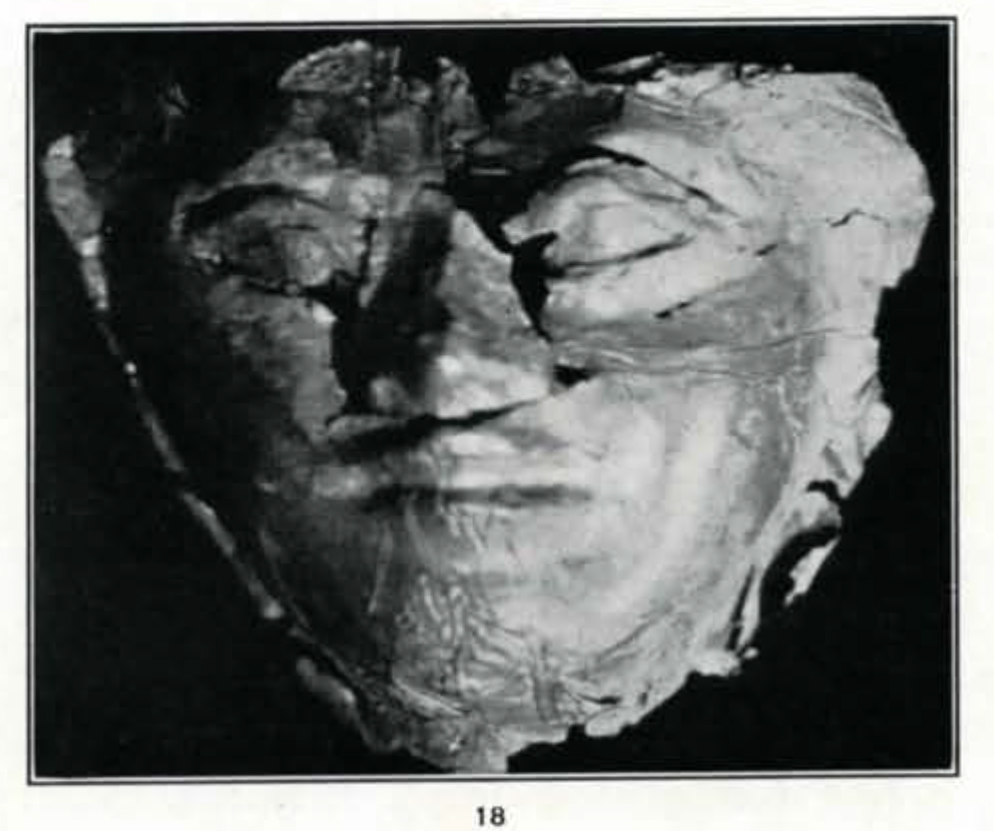

Funerary gold masks found in Nineveh, in Syria, in Hillah, and in Nippur are not unlike the masks the Egyptians used to place on the face of the mummies. They preserve the likeness of the dead when his flesh has decayed, and afford an abode for his spirit. Masks with a hole for suspension, also found in tombs, some representing bearded and grinning faces, some graceful girls or children, or even animals, were protective emblems, with some of the virtues of the original mysteriously attached to them.

The nude figurines and the dolls of the Graeco-Parthian period, abundant in tombs, have more perfection and elegance, but also a banality due to the lack of inspiration in epochs of decadence. Their sex is indicated with the reserve usual in Greece but remote from the old Babylonian realism.

Museum Object Numbers: B2539 / B1777 / B4030 / B14636

There are several types of the nude Babylonian woman. One keeps her hands joined before her in a respectful, passive attitude. The other has them slightly raised, supporting or pressing her breasts. She is undoubtedly the servant of love, presenting herself—stat nuda. This is also one of the attributes of Ishtar, the sacred prostitute of the gods. In both cases she stands up adorned only with her jewels, the locks of her hair falling on her shoulders. Sex and navel are conspicuously indicated, the pubes being a large triangular patch bordered by incised lines inclosing markings. This is also the pictograph for woman in the cuneiform writing from the earliest times. We must therefore see in these figurines an image of life, an emblem of fruitfulness, in connection with the idea of perfect womanhood. They are conformed to the most primitive instinct of man, and answer to the very name given by Adam in paradise to Eve, when both were naked and unashamed.

Later, the nude female figure was more closely associated with the divinity. It is raised on a base and must have been an object of cult. The goddess of love is borne on an animal—usually the lion—pressing her breasts or unveiling herself, and it is difficult not to recognize a nude goddess. But the magical and symbolical character of the nude woman as a token of life, an emblem of fruitfulness, and, in the tomb, as a protest against decay and an emblem of resurrection, has a large human interest that cannot be limited to the reproduction of one type of idol. The nude female figure with its secret and talismanic character existed long before it was transformed into the love goddess and made an object of cult. Far from being all images of Ishtar, the nude figurines were her model.

As a rule human representations of the gods are relatively recent. A symbol, animal, weapon, or raised stone, was at first the all-sufficient object of cult, marking the presence of the superhuman power. The oldest shrine of the love goddess may have enclosed a betyl, with perhaps a triangle incised on the surface. In the Nippur collection of terracottas there is at least one fragment—CBS. 15426—on record as being found fifteen feet below the level of Naram-Sin, and therefore anterior to B.C. 3000. It bears the triangular patch, with interior markings and traces of red colour. The rude figurine when complete was perhaps a votive offering for childbirth, or, at the time of puberty, a substitute for herself made by a Sumerian votary to the shrine; but it can scarcely be called an idol or an image of the love goddess, since probably in these early days there was no image of the goddess.

On seal cylinders the figure of the nude woman holding her breasts is not found long before B.C. 2000, precisely when the Western Amorite influence began to be preponderant in Babylonia. Northern Syria is known as the home of the great mother goddess, the nude goddess unveiling herself. But on the Babylonian seals, the nude figure is always an accessory person, drawn on a minor scale, and taking no interest in the main scene of worship. She can in no way compare with the older gods of Babylonia, who never go about nude, but are kings and queens, and never forget their mitre adorned with one or four pairs of horns, by which they are distinguished from any human being. They bear also a sceptre and wear rings, carry various weapons, and are clad in the finest royal garments. The only nude royal figure is that of Gilgamesh, a hero and a king, but he never wears the divine horns. At the utmost a little base of bricks which is sometimes placed under the feet of the nude female figure may suggest her transformation into an idol.

Image Number: 5997, 10302

Ishtar, as a goddess not of love, but of war, is fully dressed and armed, and is represented on seal cylinders and rock reliefs in authentic portraits long before the nude love goddess. She wears a shawl tied about her waist, falling to the ankles, and opening in front to give play to her bare leg in action. Above the knee is seen the lower edge of a short tunic or cuirass which has short sleeves. Quivers full of arrows and darts are crossed on her shoulders. She wields battleaxe and scimitar. As a remnant of feminine vanity, she wears below the horned mitre her long curls falling on her shoulders, while more matronly deities tie them up in a knot on the neck.

There is another Ishtar of the legend, the queen of love, who very much resembles our nude figurines, as she goes down to Hades in quest of her dead lover. At each of the seven gates she drops in turn one of her ornaments : tiara, earrings, necklace, breastplate, belt, bracelets, and anklets, until she has left only her loin cloth, which also she must discard before entering Hades. We do not know how far back the legend can be traced. Stone monuments and clay figurines give no evidence of it before B.C. 2000. Its connection with burials has certainly its deepest and most poetical expression in the myth of Ishtar and Tammuz.

“That which thou sowest, is not quickened, except it die.”

There are other figures of a nude woman as a nurse, holding or suckling a child. One of the most beautiful types may even be dated at about B.C. 2400. But it is impossible to show that we have in it a reproduction of any famous idol, like the mother goddess of Warka. These figures have been found throughout Babylonia and have nothing by which to identify them aside from their pure and beautiful humanity. Another example of the nursing mother is completely dressed in a long flounced robe, with her hair simply tied by a fillet. A nude female figure pressing her breasts is represented on a terracotta from Nippur as lying on her back on a low bed. In an example in the Yale Collection the bed is covered with a rug. A couple lying on a bed is seen on a terracotta of the British Museum. These nude figures are very human, and their symbolical and religious meaning does not transform them into idols. Archaeological truth is the result of a series of observations and comparisons between a large number of examples, and it cannot be anticipated.

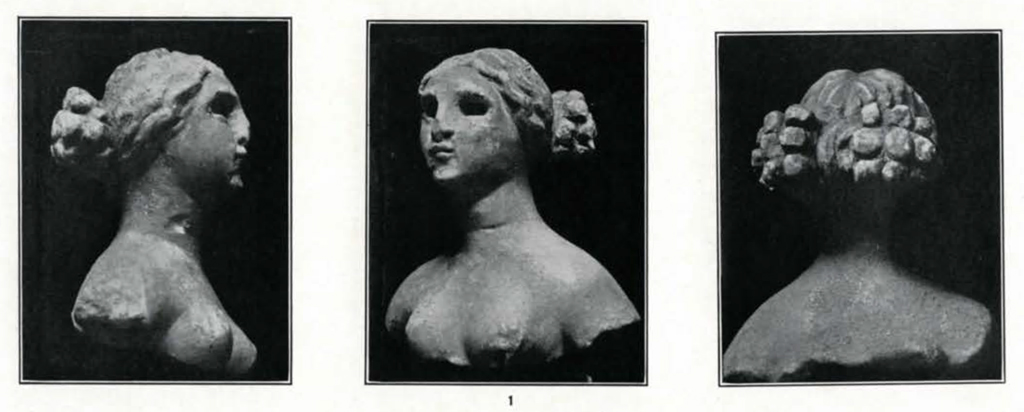

- Alabaster statuette. A nude female figure of the most charming grace and beautifully modelled. Arms and body are unfortunately broken off below the breasts. The head is slightly inclined, the neck with its two folds in front, the shoulders and shoulder blades, and the firm round breasts are cut out of the luscious alabaster by a masterly hand with a vivid sense of life, in the best tradition of Greek art. The large eyes were originally inlaid with precious stones and must have added a new light to the beautiful though rather short and round face. The nose is almost straight, but its tip has been broken off. The hair is parted and waved and tied on the nape of the neck in two large masses of short curls after the fashion of the Roman ladies of the first century. If there were any gold ornaments, they have disappeared and left the statuette in its simple and delightful grace as it came from the hands of the sculptor.

CBS. 3988. Presented to the first Nippur Expedition in 1889 by Mr. Coleman, engineer, as coming from Babylon. 60 X 34 mm. - Nude figure of a young goddess. With one hand she is covering her breast. The other was probably held in the traditional attitude of the Greek Venus, represented on terracotta reliefs decorating slipper shaped coffins of the Græco-Parthian period. Unfortunately the right arm and the lower part of the body are broken off. The hair is parted and waved and falls in long tresses on the shoulders. It is also tied in a bow above the head after the style of other young goddesses. One shoulder is slightly depressed, conveying a feeling of action and life unknown in the older hieratic statuettes of Babylonia.

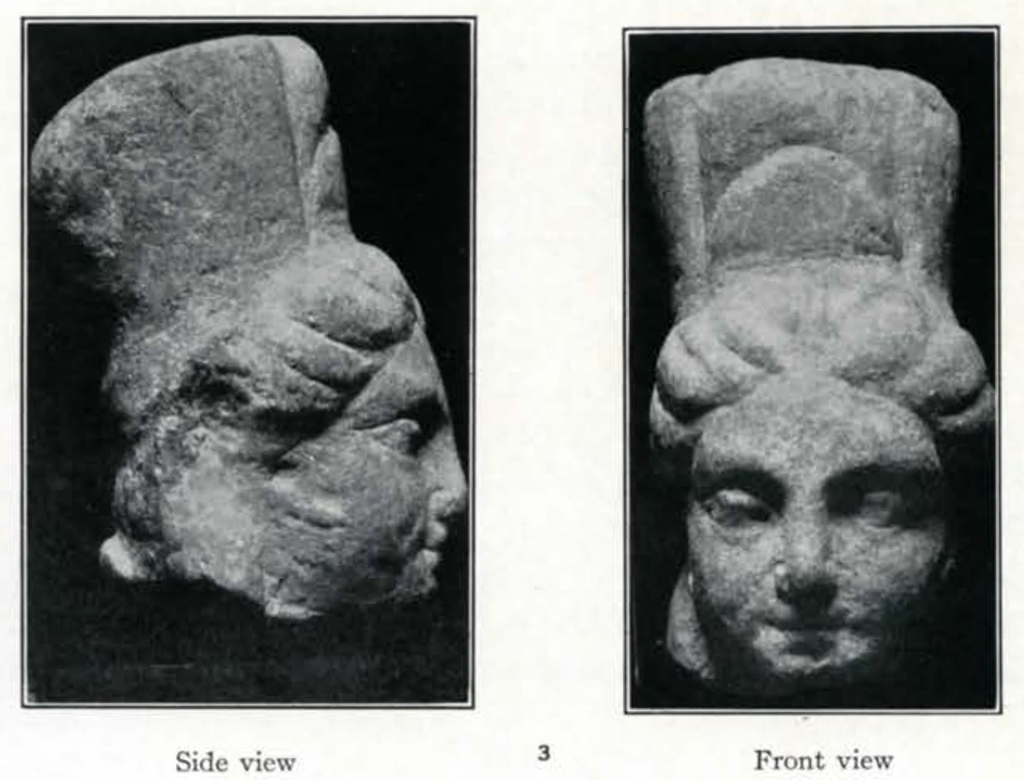

CBS. 9368. Bought by J. Haynes in North Syria before 1899. White marble. 125 X 84 mm. - White marble head of a young goddess, of the Greco-Parthian period. Above her parted and waved hair she wears a high mitre or calathos adorned in front with a semicircle between straight lines which probably represent a metal band.

CBS. 9365. Bought by J. Haynes in North Syria before 1899. 80 X 48 mm. - Nude female figure reclining on a bed. The lower limbs are partly covered with a thin drapery. The other end of the same long veil or scarf is thrown over the left arm and the light fluffy material sets off by contrast the complete nudity of the woman. She is another Venus resting confident in the triumph of her perfect beauty. The arms were worked separately and attached. The right arm

- Fragment of a little bone figurine like the above.

CBS. 6180. Probably brought by H. V. Hilprecht from Hillah

in 1889, but unregistered. 37 X 20 mm. - Little bone head of a similar figurine.

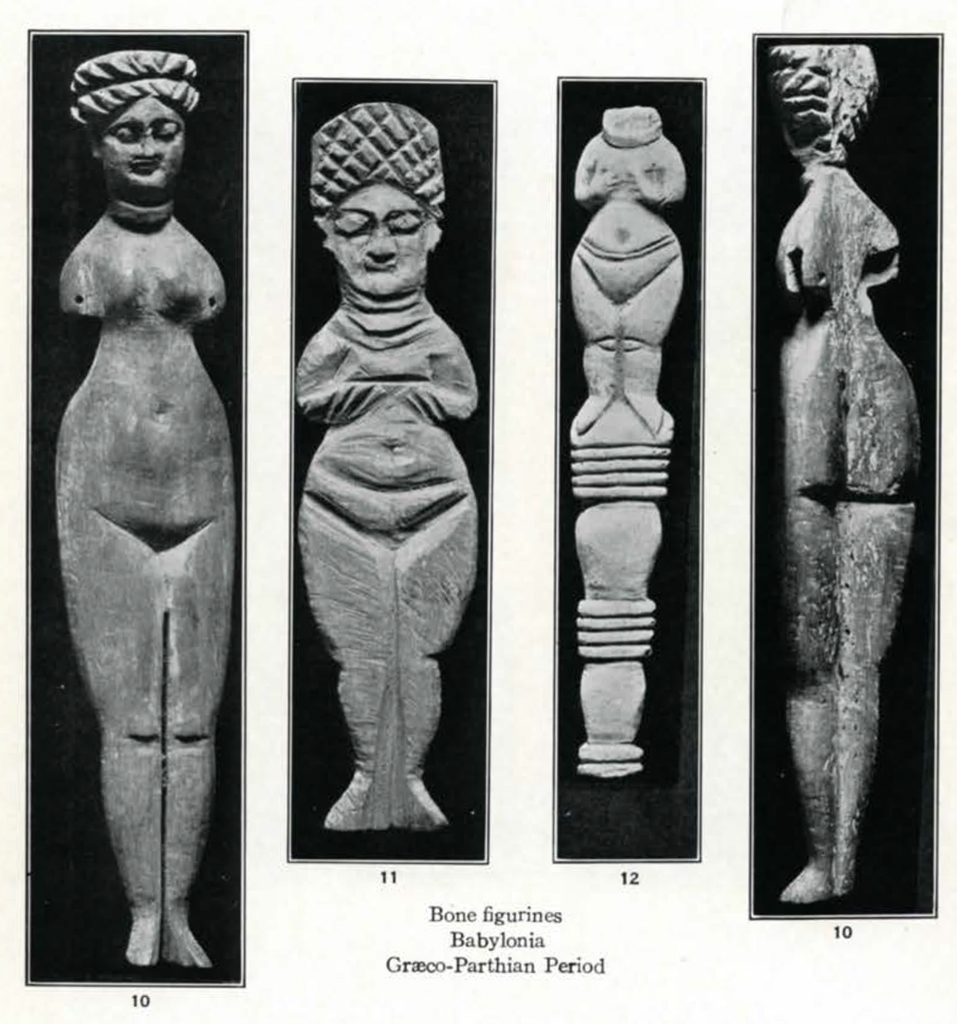

CBS. 14386. Unregistered. 20 X 17 mm. - Nude female figure, wearing only a necklace and having her hair plaited and crossed by a fillet. This is a bone figurine with separate arms attached by a wire through the shoulders. The pubes and navel, small breasts and large hips, the feet and knee caps are carefully modelled and accentuated. There is in the figure a smoothness and elegance proper to Greek art. This little figure was probably not used as a doll, but is a new form of funerary Ishtar, the triumphant symbol of life buried with the dead.

CBS. 8997. Brought probably from Babylon by the second Nippur expedition. 124 X 25 mm. - Bone doll. Nude female figure as before, but of much coarser workmanship. The arms are not separate. The hands are placed under the breasts. A high calathos seems to cover the head.

CBS. 9026. Brought probably from Babylon by the second Nippur expedition. 95 X 25 mm. - Same figure as before, but mounted on a shaft decorated with rings, and wrongly called a hairpin. The long point was used to fix it in the clothing of the dead or in the ground.

CBS. 5984. Cast. Original missing. Unregistered; but probably found in Babylon. 88 X 15 mm. - Little nude figure as above (Nos. 6 to 9), but seated with the left knee drawn up and the right leg bent under; same confusion of sex; same headdress with three points, and left hand holding the breast or an undefined object. The figure probably represents the young Tammuz, comparable with Horus or Adonis. Bone (or ivory) carving.

CBS. 2539. Brought back by the second Nippur expedition. Probably bought in Hillah by H. V. Hilprecht, like the following number. 40 X 20 mm. - Little nude bone (or ivory) figure of a seated boy like the above.

CBS. 1777. Brought back by H. V. Hilprecht in 1889. 58 X 20 mm. - Little nude bone figure seated as before, but connected by a long shaft with the head of what must have been a nude female figure. This would complete the cycle of the legend, combining the two persons of Ishtar and Tammuz.

CBS. 14636. Unregistered. Probably found in Babylon. 89 X 11 mm. - Head of Ishtar, long shaft and seated nude boy as before.

CBS. 4030. Bought by the first (?) Nippur expedition. 85 X 11 mm. - Same object as above. Only the head of Ishtar and the shaft are preserved.

CBS. 323. Bought from J. Shemtob in London, in 1888. 66 X 12 mm. - Mask made of thin gold leaf, and probably found in a

Parthian tomb by the fourth Nippur expedition.

Known only from a photograph, No. 215, taken in the field.