IT is a pure joy for a weary archaeologist to plunge into a study of Oriental art—the oldest known Mesopotamian art—thanks to the rich collection of objects, figures, statues, reliefs, and engravings discovered in the predynastic cemetery at Ur. A new stage of civilization, perfectly unknown a year ago, has now been reached. And to our great surprise, out of the mystery of the past beauty shines with a wonderful glamour. Gold and silver, blue lapis and red carnelian, mother of pearl and shell inlay, lavishly used by the Sumerian artists, show their good taste in the blending of colours, their mastery in the lines of the figures, the boldness and force of their drawings, which have a primitive charm and a subtle refinement such as we find at first hard to reconcile with so early a date. Many of the objects recovered, like the harp, the gaming boards with their sets of ‘men’ and dice, the golden comb so like a Spanish comb, the rings and garter of the queen, the fluted gold tumbler and the chalice, the chariots and their teams, all seem wonderfully familiar and close to us, while the wholesale murder and burial of servants and retainers round the grave of their lord and lady hint at grim customs of hoary ages.

Museum Object Number: B17694B

Image Number: 8268

Such beautiful objects were not the work of beginners. Civilization even then was an ancient achievement in Mesopotamia, whence it spread westward. Where shall we look for or place its origin? We do not know. But obviously the old Sumerian art at Ur is already a classical art, with fixed types and school conventions. Modelling, casting, carving, and engraving have no secrets for the expert craftsmen. Their best pieces of work show an ideal of force and dignity not devoid of a certain heaviness, a minute rendering of details, a love of nature and animal life. It is a subtle and curious art which likes inlay and polychromy, delights in the mingling of colours and materials, the blending of low and high relief with boldly salient parts in the round. Its style is surprisingly free and is not abashed by the difficult tracing of figures en face, or the shortening of proportions in perspective. It has even an apparent sense of humour, probably with a deeper meaning, in scenes where animals are given the attitudes and play the parts of men : a dog carries a small altar loaded with offerings, a lion follows him bringing a lamp and the wine of the sacrifice. It is remarkable that the animals are by degrees transformed and given the head, face, locks, beard, arms, feet, and torso of man. We have composite monsters, a bison with a human face, a scorpion-man, a donkey seated and playing the harp with his fingers, a rampant gazelle holding two tumblers, a scaled monkey (?) playing with a rattle and drumming on a board.

This is pure mythology. We are introduced into a world in which animals can play and talk like men : a land of fable such as has always enchanted and will still long delight the children of men. And by the by, that marvellous curled beard hanging below the chin of the man-faced bison is not at all an emblem of divinity, but a sign of human virility. The horned mitre with one, two or four pairs of horns is the only certain emblem of divinity, both for gods and goddesses. So the bull might be a god, even without a beard. The crescent horns are the emblem of the Moon God, called the young bull of heaven. That mighty blue beard simply brings him one step closer to humanity, and may or may not decorate the golden head which animates and gives a voice to the harp “roaring like a bull.”

And here we find a very important link between the old Sumerian art of Ur and the still earlier Elamite civilization—about 4000 B.C.—known through the French excavations at Susa. It is remarkable that the old Elamite artist in all his painting and carving and engraving “never represents a god under human form. But he multiplies animal figures, especially figures of wild species, and gives to them strange attitudes and human gestures. His imagination creates composite monsters, dragons and griffins. And when he reaches a higher stage, it is in scenes where the figures of Gilgamesh and Enkidu are conspicuous and betray a close relation with Babylonia.”1

Image Number: 8962, 8963, 191116

“The Gilgamesh and Enkidu contests with wild animals are simply the heroic development of natural hunting scenes by which a contact is established with the archaic or Elamite period. The worshipping of gods in human form with crowns, sceptres, and thrones like kings is a new feature of the Sumero-Akkadian civilisation apparently unknown to the pre-Elamites—and to the predynastic Sumerians of Ur. It supposes regular institutions, city states, courts, and temples modelled on the courts. It expresses a higher ideal of worship no longer limited to stones, animal figures, weapons, and emblems, but to gods akin to humanity.

“Between these two extremes: heroic hunting and regular court worship of the gods, there is a large intermediary layer of mythological figures which seems to connect them and where we see the human god emerging from the beast, or in close contact with the primitive forces of nature. . . . When the gods attained full human stature and royal dignity, the world of heroes and demigods always had a number of bullmen, lionmen, birdmen, fishmen and scorpion-men; while the pure animals: bull, lion, dragon, bird, fish, serpent, scorpion, become simple followers, emblems and servants of the gods.”2

The eagle, a royal bird, has never attained, as an emblem of divinity, to the popularity of the bull. The eagle triumphs over wild animals, bull, bearded bison, and others. Eagle feathers decorate the heads of Sumerian chiefs, or are an ornament between the horns of the oldest mitre. But they soon disappear and are replaced by two or more pairs of horns, the round crescent horns of the bison, the accepted emblem of divinity. Anthropology and archaeology are both interested in that primitive heraldry. The war eagle of the gods of the atmosphere is the lord of all the creatures of the pasture land. Is not the Moon God like a great bull moving across the pastures of heaven? All Sumer rejoices when his golden horn shines over the horizon, bringing in regular succession months and seasons and years. He is only the son of the god of the atmosphere but he is the guide and teacher of the Sumerian tribes and of their pastors, and his golden crown has impressed them as the highest emblem by which they can distinguish heavenly powers.

Image Number: 8962, 8963, 191115

The happy restoration by the British Museum experts of some of the magnificent objects of art taken from the predynastic cemetery at Ur and their recent publication will be welcome to the readers of the JOURNAL. They will admire the stela or standard with six rows of Sumerian figures and scenes of peace and war cut in shell and inlaid on a background of blue lapis; the sounding-box of a harp decorated with inlay, engraved plaques, and a bull’s head in gold and lapis; another bull’s head in gold and lapis, part of a statue or probably of a second harp; finally a rein ring in silver surmounted by a bull mascot from the king’s wagon. In the field of the past, the mist is slowly lifting, leaving a bright golden spot in the muddy plains of Mesopotamia, where Shub-ad was once a queen and Meskalamdug a king in ancient Ur, more than five thousand years ago.

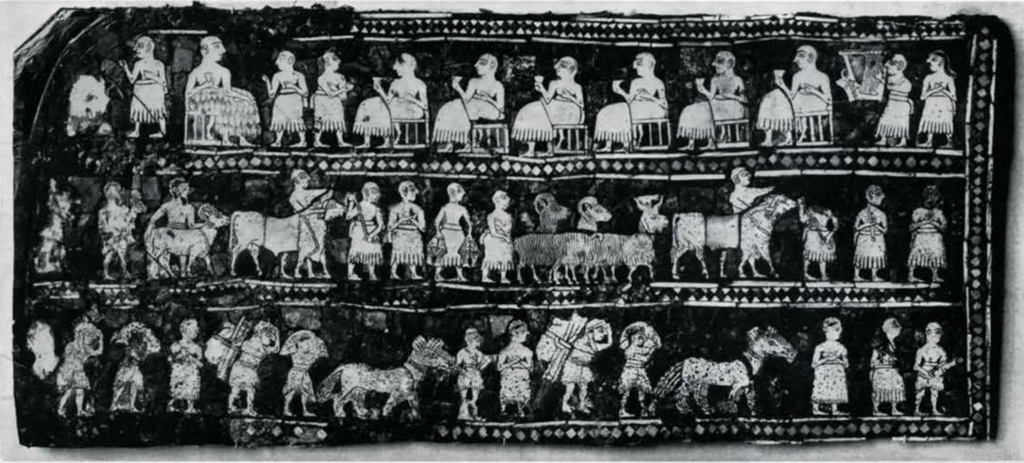

The Inlay Stela

It seems almost impossible ever to satisfy our curiosity by looking at the world of little Sumerian figures crowded in the six registers of the stela and in the two triangular ends. The whole is only 32 inches long, but there is such a variety of action, such a sense of life, with so many different costumes of the king, of his officials and his servants, such a display of arms, cloaks and helmets, such a contrast between the victors and their tattooed enemies, such a fascination about the chariots, their drivers, their men-at-arms, their teams of asses and their harness, that we gaze again and again, afraid to miss a single detail of that wonderful picture of ancient Sumerian life. The king is the real war lord. His figure is drawn on a larger scale and stands in the middle of the upper register. He carries in the right hand a curved club, his sceptre, and in the left, a lance with a large leaf-shaped head. Prisoners are brought one by one to him, and foremost one who is probably the chief of the defeated enemies. The king has alighted from his chariot and is followed by his bodyguard or by officials of high rank, armed with battle-axe and lance. The king, his guard, and his soldiers all wear copper helmets covering the ears and tied with a strap below the chin. Some of the original helmets have been recovered in the excavations and the type strangely recalls some helmets of the crusaders’ time. Lances and axes also have been recovered of the very type represented on the stela. The best gold models must have been the weapons of the king. The proper Sumerian dress is a kilt with long laps, closing behind. Originally a fleece, it may later have been made of woollen material with long thrums woven in on one side in imitation of the fleece. A second piece of the same material—called kaunakes—was thrown like a plaid over the left shoulder. The whole army was shaven and shorn according to Sumerian tradition, and went barefooted, which was no inconvenience on the soft muddy soil of Mesopotamia. Of course a wadded lining was fixed inside the helmet; traces of one have been found inside the golden wig.

The king’s chariot is of the common type of that age, with four wheels, side and back panels, a high front board, and a curved pole rising high and supporting a rein ring behind its junction with the yoke. A diminutive groom, his whip resting on his shoulder, leads the royal team of great mules or asses. The man-at-arms or henchman follows on foot behind, holding the reins in his left and his battle-axe in his right hand. The reins lie in the V-shaped notch cut in the top of the front board. A large quiver full of spare darts and lances hangs on the left horn of the same board. A leopard skin or blanket is thrown over the back panel and covers the step on which the second charioteer will stand during the action, protecting the driver fighting in front. The front board is reinforced by cross pieces, the sides are divided into three panels by straight bars. State chariots decorated with an inlaid pattern of shell and lapis, and lions’, bulls’ and leopards’ heads in gold and silver in the round have been recovered in the royal tombs. These were not war chariots but rather belong to the sumptuous type of coach which Ishtar devised as a reward for her lovers: “I will harness for thee a chariot of lapis and gold, with wheels of gold and horns of diamond. Daily shalt thou harness the great mules.”

Image Number: 8964, 191117, 191118

Ishtar herself, the august princess of Uruk, who inhabits a house of gold, drove a team of seven lions. But this is pure mythology. The king’s own team was incontestably a team of four mules or donkeys. For the first time we have a clear, complete picture of the animals with body, hoofs, head, and tail, and they are neither horses nor lions nor bearded bulls nor dragons, but asses, which is very satisfactory. What seems to be the long hair round their necks is neither mane nor beard, but artificial braids of hair or wool attached to the collar like an ornament or to drive flies away, a practice very much in honour among the Assyrians and still observed in many parts of the world. The reins were attached to a ring in the animal’s nose. Silver collars and silver rings have been found in the royal graves, providing evidence that teams of bulls were used as well as teams of asses.

The plain wooden wheels made of two semicircular pieces joined by copper clamps or bands round a central core, have excited the enthusiasm of archaeologists. The wheel, a great human discovery, was in use at Ur more than fifteen hundred years before it was imported into Egypt. There are several models of wheels which show that the central core was either round or lozenge-shaped. The wheel was probably solid with the axle which turned with it in a groove below the body of the chariot. A copper pin or bolt sometimes secured its connection with the axle. In any case the early Sumerian wheel was massive and not yet made more graceful or lighter by the use of spokes. Big knobs of metal sometimes rein-forced the rim. Mr. Woolley has suggested leather tires. The only wheelband discovered at Susa was made of six bronze sections riveted together and forming a complete circle embedded in the rim.

Centuries later Gudea, another prince of Sumer, was ordered to build the royal chariot of his god: “Break the seal (of the doors) of thy treasure house; bring wood out of it, and build a complete chariot for thy king. Harness to it the donkeys. Adorn the chariot with metal and lapis inlay. Darts in the quiver shall shine like the day. Take good care of the ankar, the arm of bravery.” Gudea brought out his most precious timber, esalim-wood, mêsu-wood, huluppu-wood. He completed the chariot and harnessed to it the great Uk-kash donkeys. The chariot shone like the stars in heaven. The donkeys were of the famous breed of Eridu, and the driver Ensignun could drive like a storm. It was an irresistible machine of war: ” The chariot named Kurmugan, was loaded with splendour, covered with brilliancy. With its donkeys, its groom, the seven-headed club, the terrible weapons of the battle, the weapons which no country can resist, the deadly weapons of the battle, the Mi-ib, with a lion head in hulalu stone which no land resists, the sword with the nine emblems, the arm of bravery, the bow which sounds like a (forest), the terrible arrows of the battle which dart like lightnings, the quiver out of which wild beast and dragons let hang their tongues, arms of the battle to fulfil the orders of royalty, all this was a present of Gudea, builder of the temple, patesi of Lagash.”

All the prisoners brought in to the king are nude except the first of them, who wears a short fringed kilt, but he is so indistinct a figure that it is hard to decide whom he represents, probably the enemy king. All have ropes round their necks and their arms tied behind their backs. They are shaven and shorn like their Sumerian opponents and it would have been difficult to distinguish one from another if the enemies did not have marks—war paint or tattoo?—all over the body, on skull, cheek, chest, and thigh. Or are these marks of the wounds inflicted by the battle-axes and lances which we see in the hands of the soldiers, a graphic representation of the blood trickling from the cuts in the flesh? There is a certain freedom of style in that otherwise monotonous procession. Not one figure is the exact copy of the other. The groups are not rigidly the same. Two prisoners are marshalled by one man—if this is the original order? All the soldiers do not carry the same weapon. Their proud attitude, with heads erect, contrasts with the downcast look of the prisoners.

Museum Object Number: B17694A

The army in action is displayed in the next two registers. It is divided into two corps, the foot troops and the charioteers. And we cannot help admiring the free imagination, the naive charm in the forceful presentation by the primitive artist of a battle scene so full of life and motion. The solid legion has formed a line with lowered lances pointing forward. All wear the uniform : the scalloped kilt, the copper helmet fixed by a strap under the chin, a mantle covering both shoulders and fastened by a clasp on the chest. The dots in groups of three, four, and five which decorate the mantles make the soldiers look like the pieces of a game of dominoes, giving somehow the impression of knaves in a pack of cards, which would have pleased Alice in Wonderland. In fact these are not dots but the spots of leopard skins, as we see from the animal represented on the triangular end. The skin served as a material for the soldiers’ heavy coat, which was thrown over the back of the chariot when not used, or spread on the seat as a blanket.3 Nothing could disturb the order of this solid rear line. Their grasp on their lances betokens perfect drilling, and while the practised eye of a sergeant-major might see irregularity in the openings of the mantles, the ordered tramp, tramp of their feet would have swollen with pride the builder of an empire. Three sons of an old Sumerian king on a famous limestone relief4 wear their mantles in the same manner, fastened with a clasp and covering both shoulders. The soldiers of the front line are already engaged in an action, the issue of which is not doubtful. The enemies are prostrate, wounded, stripped, bound, and captive, so dexterously can the Sumerian warrior handle battle-axe and lance, as shown in three different groups. One prisoner is being handcuffed. The soldier next to him brandishes his lance over a fallen enemy. The third wipes the blade of his axe and feels the cutting edge after dealing a blow. The bodies of the fallen enemies are drawn with much liberty and a daring attempt at perspective and foreshortening of proportions, both here and in the case of the bodies of the enemies run down by the charioteers. The Sumerian soldier in action has discarded his great mantle and thrown his plaid over his left shoulder. A fringed stole over the left arm of one of them is an unusual garment, perhaps the loin cloth of the enemy and a part of the spoil which belongs to the victor. More enemies, nude and wounded, are driven on by the charging infantry. Some of them still keep their lances and their loin cloths closing in front and having narrow fringes. The fight is over and they are fleeing, while one unfortunate man casts a last look on the scene of battle. This part of the stela has evidently suffered and two half figures of men, one nude and the other wearing a loin cloth, have been jumbled together.

The charioteer scene is a pure delight for anybody who has witnessed a charge and the long lines of horses sweeping, wave after wave, through the golden dust. If the first team of asses walks composedly enough, the second has struck a lively pace which becomes a full gallop and a mad dash in the last two. The foremost driver with his goad or two-pronged dart and his henchman brandishing a lance is thrown backwards and the man on the step has to hang on desperately. Their raised heads answer to the raised heads of the animals, to their springing bodies and their flowing tails. Weapons, lances, axes, dresses, helmets, kilts, and plaids are the same as those worn by the infantry. The crumpled nude bodies of the enemies litter the ground.

The reverse is not less interesting. Here we see the pleasures and abundance of peace opposed to the violence of war. The king presides over a banquet amidst his sons or officials and drinks a cup of the best mountain wine. The seats are remarkably elegant. Servants hustle about and a woman singer, we imagine, recites in cadenced verses the great actions of the battle accompanied by the harpist striking in time the eleven cords of his small harp. So the women danced, and sang that King Saul had killed his thousand but David his ten thousand. In the registers below there is a real pageant of servants bringing the requisites of the feast and also the spoils of war. Bulls, goats, a ram, a lamb, and four big carp fresh from the river will supply a royal meal. The safe leading of the lively bulls is no easy matter. A rope is attached to a ring in the beast’s nose, and the first cowboy pulls it high to prevent any unruly tossing, while the second has wound his arms, like a wrestler, round the threatening horns of the bull, ready to throw it. What would our Wild West think of that ancient East? The manner in which the shepherds carry a lamb—or is it a young gazelle?—or hold a ram by the curved horn and fat tail has not changed since those early days. The goat-herd armed with a short stick or a whip drives his animals from behind. For accuracy the heads of the goats nos. 2 and 3 ought to be placed a little forward to balance properly over their forelegs. Goat no. 1 belongs to a different species, the Markhur goat, with spiral horns, long pendent ears, a beard, and a tucked-up tail. A headman carrying his staff of office introduces the procession, which is divided into two main groups headed by figures with clasped hands. These have no special attributes and are perhaps foremen or officials.

In the last register two teams of asses with their drivers, and pack carriers of two types are divided into two or three groups headed by their foremen, if such are the figures with the clasped hands. The first driver walks rope in hand at the head of the procession and evidently ought rather to be placed at the head of his asses, which is his proper station as exemplified by the second driver. One of the pack carriers bears the bundles on his shoulder but the second uses a framework resting on his back and secured by a rope passing round his forehead. This way of carrying heavy burdens strangely recalls Indian basket carriers or jar carriers from old Peru. The carriers and the foremen have long hair, the asses’ drivers are shorn like the rest of the servants above, except the men who bring the lamb and the ram, who wear long hair and beards. This may be a professional as well as a racial distinction. Bedouin shepherds in the desert let their hair grow. But slaves and prisoners of war of different races may have kept their own mode of hairdressing and costume. It is remarkable that all the figures in the last register wear a kilt closing behind or a loin cloth opening in front, with short fringes. The kilt with short fringes is very different from the kilt with long laps worn by the Sumerian officials, or from the better one worn by the king. The loin cloth opening in front is the proper dress of the vanquished enemies. The careful drawing may correspond to a difference in race and rank and also to a difference of material, wool or linen. The only figure—unfortunately incomplete—in the third register who wears the Sumerian kilt with long laps which closes behind, is probably another headman introducing the second procession.

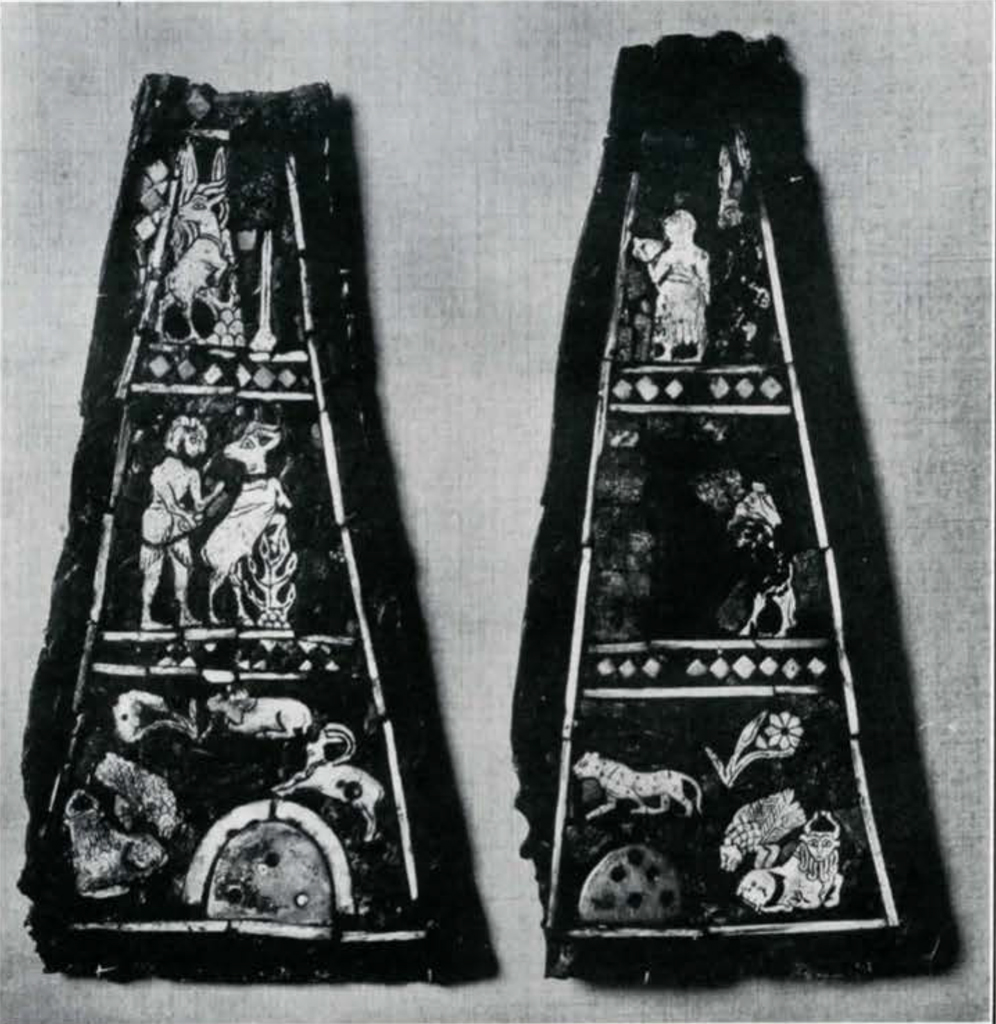

Image Number: 191106

Animal figures borrowed from the common repertory of heraldry and heroic hunting fill the triangular ends of the stela. We have the passant leopard, the couchant lamb, the rampant goat, the conventional branch and star flower with eight petals, in a landscape of hills represented by a pyramid of dots or curves. A hunter, dagger in hand, has seized about the neck a rampant ibex caught amidst bushes and hills. The hunter may be a hillman, an Elamite, with long hair and beard (?), very different from the completely shorn Sumerian. He wears the fringed loin cloth of the enemy, closing in front. The lines of his body are more elongated and graceful, the knees are bare for action. The typical, shorn, stumpy Sumerian wears a bell-shaped woollen kilt closing behind. The long laps hang down the middle of his legs. The panels are reconstructed and the scene is not clear, but he is certainly not a hunter, and is probably raising his hand for some ritual action. The goat rampant amidst bushes and hills with head turned back is probably out of position, and the straight post supporting an emblem5 is the object which ought to have been placed in front of the Sumerian worshipper. The middle, incomplete panel certainly represented a fight between bull and lion as seen below in the decoration of the harp.

The very ancient mythological group of the lion-headed eagle perched on the back of the bearded, man-headed bison, which he masters and lacerates “unguibus” if not “rostro,” deserves special attention. The composite monsters are in the tradition of archaic Elamite art. The mythical bird is the master of the bull. By no means is he picking off flies and bugs as has been irreverently suggested. The eagle is above all an emblem of royalty, domination, and power, and such has been his meaning through the ages, whether he flies over the heads of Assyrian kings, or before Roman legions, or on Greek, German, French, or American coins. The spread-eagle found in so many coats of arms of old Sumer and of modern countries is the triumphant bird seizing its prey with its talons. He is the emblem of gods of war worshipped in different cities under different names, Ningirsu, Nin-Urash, In-Shusi-nak. Under the name of Imgig he figures in the coat of arms of the city of Lagash, devoted to Ningirsu, where the type of an eagle with a lion’s head is well established and is contemporary with the drawing of many figures in full face. But there was more liberty in the past and we find spread-eagles and eagles in profile, with normal heads and with lions’ heads, capturing two animals or perching on the back of one. Their prey may be bulls, antelopes, lions, stags, ibexes, even ducks.

The bull may be passant, couchant, or rampant. It may be the wild mountain bull with widely spread horns, the primitive urochs, or the bison with crescent horns and long locks, which in old Elamite drawings has tufts of hair below the chin. The last has been transformed into the man-headed bison which has the face of Gilgamesh, before it becomes the bull-man Enkidu. The spread-eagle may even have a double lion’s head, which was a favourite device in the time of Gudea and on a few ancient Elamite seals, but he should not be confused with the birdman Zü, who steals the tablets of destiny, carries the dead bison on his shoulders, has a wife and son, and is killed by Lugalbanda in Khashu, the unknown mountain. Many a seal in the Museum collections represents the capture and judgment of the Zü bird and his disgrace, which can never be imputed to the royal Imgig bird.

The inlay stela,6 according to Mr. Woolley, is as a work of art unparallelled, as a historic document invaluable. It was found beside the shoulder of a man buried in a side chamber of the oldest of the royal tombs, almost intact as it was executed by the craftsmen of 3500 B.C. It is an elaborate example of inlay work in shell, lapis lazuli, and pink limestone. The two large plaques were set back to back at a slight angle, with the triangular pieces between their ends, and the whole may have been mounted on a pole so as to be carried as a standard. The tesserae had for the most part not shifted from their position. What is shown here is not a reconstruction but the original mosaic. Some of the border has been restored; only the triangular ends had been seriously broken up.

The Harp

Image Number: 191107

The harp is the instrument of the poets, the support of the aerial words in which they enshrine joys and sorrows, memory of the past and hope immortal. David sang to the harp to soothe the brooding heart of Saul. A harpist and a woman singer stand by at the king’s banquet. Gudea of Lagash presented to his god Ningirsu “his beloved harp named Usumgal-kalamma, the sonorous and famous instrument of his council. The portico (?) of the harp was like a roaring bull.” It served to accompany the sacred prayers which were said in the court, together with the clang of the cymbals. “Along with the flute it filled with joy the courts of the temple.” The temple singer used it “to appease the heart, to please the joyous humour, to wipe tears from the eyes, to release the pain of the suffering heart.” The singer in his recital is likened to “the storm of the Ocean, to the tempest on land, to the soft purifying waters of the Euphrates. The young girls of the harem, the seven twins of the goddess Bau, placed close to him, pronounce the good words. With the flute, the cymbals, and the harp they fill with joy the courts of the temple.”

The harp of Gudea is represented on a limestone relief. It is rectangular in form, with a large sounding-box and an upper bar in which the keys are fixed. It has eleven strings spreading fanwise from the box to the upper bar, towards the left angle behind which sits the player, playing with both hands. A passant bull, probably of gold, stands on the sounding-box, and another bull’s head decorates the front of it.

The little harp represented on the stela also has eleven strings, and is decorated with a bull’s head. The sounding-box has the shape of a couchant bull, with an inlaid collar and an inlaid band across the body. The harpist plays while standing. A band passing over his shoulders may help to carry the instrument. An opening in the sides of the box makes the sounds clearer and mellow.

Another type of harp with eight strings is represented on a shell plaque to be studied below. It is played by a seated donkey and belongs to a very interesting mythological series. With three other plaques it was inset as a decoration below the splendid horned bull’s head in gold, with its large beard of lapis. Bull’s head and plaques were possibly part of a harp of the same type.

The harp found in the queen’s grave had also a sounding-box decorated with a calf’s head of gold and lapis, with shell plaques engraved with mythological subjects, and with bands of inlay.7 The woodwork, which had perished, has been carefully restored in the British Museum. According to Mr. Woolley the harp has twelve strings, but the position of the keys on the upright is not clear, pending further restoration. The calf’s head and the engraved plaques deserve attention.

The calf’s head, without horns, which decorates the queen’s harp, is made of gold and lapis, like the bull’s head found in the king’s grave, which may also have been part of a harp. Both are wonderful examples of ancient Sumerian art. The same technique was applied to both.

“The head all except the ears and horns was hammered up from a sheet of thin gold and set over a wooden core. The horns and ears made separately were fixed to this. Under the chin a deep cut was made in the wood, the edges of the gold being bent into the cut, and here was inserted the beard. The base of this was a wooden board on which the tresses cut of lapis lazuli were set in bitumen, while the back and sides of the board were concealed by a plate of thin silver seamed by silver nails. The upper part of the woodwork went right up into the wood of the head and was made fast to it by nails driven through the crown. The gold did not cover the crown at all. Here the wooden core left exposed was coated with bitumen and into the bitumen were laid the lapis lazuli locks of hair, each separately carved.

“The eyes of white shell with lapis pupils enclosed in eye sockets of lapis were secured by copper bolts to the wood core of the head. The many superciliary folds are typical of Sumerian art. A strip of gold nailed on behind the horns completed the neck and a narrow band of mosaic in shell and lapis formed a collar to mark the distinction between the metal head and the wooden body.”

These are beautiful pieces of work, curious and refined. The association of full and low relief with engraving betrays the very spirit and taste of ancient Sumerian art. The result of such inlay is very striking. The polychromy of the materials, shell, lapis, gold, red limestone, and bitumen adds new unforeseen effects. The animal forms are heavy but original and powerful. The types, studied from nature in familiar attitudes, are strikingly true. The first sketch fixed the essential forms of each species. The artists of the best periods will have nothing to change to reach perfection, more refinement but not more character.

Museum Object Number: 29-22-9

Image Number: 8970, 191099

Animal life is a favourite motif of Sumerian art. The animals are drawn in familiar poses, couchant, rampant, running, fighting, according to well-established types. Legendary and fantastic compositions alternate with these monotonous repetitions: lion-headed eagle, bearded bull, scorpion-man.

Sumerian religion gave a large place to spirits, demons, genii, embodying natural forces. This religious and primitive instinct of the race inspired the artists to create monsters, fantastic beings composed of several animal forms, which were sometimes combined with human forms. In Elam long before, when no god had ever been represented as a man, the animals were given strange human attitudes, in an effort to express the mens divinior.

The bearded bison was known to and represented by Elamite artists, with graphic details of locks and tresses, which the wild bull can never claim. But the actual blue lapis beard below the golden head is a human attribute of the hero-hunter Gilgamesh, mighty as Nimrod. The proper attribute of the gods, under human form, is the horned mitre. It is true that the great Moon God of Ur is called the young bull of heaven and his blue lapis beard is famous in religious poems. But the divine harp, Usum-kalamma, roaring like a bull, is not necessarily the great Moon God Nannar or any great bull of heaven.

The front of the harp below the golden calf’s head is decorated with four shell plaques engraved with animal figures, in natural or fantastic composition. Engraving on shell is a purely Sumerian art. The drawing is done with a hard point on dull shell with scarcely visible relief. The plaques of shell of small dimensions were cut from the pivot axis of certain univalve shells of the species trito or melo. Drawing with the point is the most primitive, the simplest, and the most abstract form of art. Bodies are reduced to a single contour line with no thickness. Engraving and drawing are one at first, whether on metal, shell, or mother of pearl. Strength is the ideal of the engraver. His tracing is surprisingly strong, somewhat heavy but full of expression, done with a very accurate hand, but cutting a uniform line. Even inside the contour, the tracing of muscles or the detail of manes and feathers is not a shade lighter. The ambition of the artist is strong uniform work in sharp contrast on the white background. The filling of the lines with black and red paint betrays his delight in life and colours.

Each subject is framed by a straight border line. The intentional order of the figures, the need for symmetry and the heraldic composition of confronted animals is from the beginning the characteristic mark of Sumerian decorative art. Figures en face, always very difficult, and the abundance of minute and systematic details are a daring attempt at reproducing life. There is the same power in the daring attitudes, the heads turned full face, the raised tails, the bristling manes full of a rude energy.

The four subjects selected are the lion-headed eagle seizing two leaping ibexes—or antelopes (?); two bulls rampant in a thicket of plants; the bull-man Enkidu holding up two leopards by their hind legs; a hunting lion at grips with a rampant bull, seizing its neck in its jaws.

The lion-headed eagle alighting on the back of a bull, bearded or not, is one of the strongest motifs in the old Sumerian picture gallery. The same figure in the same angular, rude style is found on several primitive seal cylinders. The spread-eagle is a military emblem on the Stela of the Vultures. The spread-eagle with a lion’s head, seizing in its talons lions, stags, gazelles, bulls, ibexes, or ducks, is one of the fantastic composite animals of the archaic Elamite style. In Sumer it has become a heraldic device, the coat of arms of many war gods, Ningirsu of Lagash, Ninurta, and probably In Shushinak of Susa. His name is the Imgig bird. He is not flying, but has wings spread and flapping in the act of seizing his prey. Pieces representing a feather, cut in red limestone, white shell, and black bituminous stone have been found at Lagash. All are pierced at the back for attachment by copper wire to a wooden board. When assembled they must have formed the wings, body, and tail of the Imgig bird in natural proportions. The red, black, and white must have been contrasted in the checkered lines of colours as represented on the engraved plaque. Separate heads of lions, or of lion-headed eagles in the round, with a mortise for the reception of a tenon at the back must have completed such decoration in the style of the reconstructed Imgig panel of Al ‘Ubaid.

On the engraved plaque the neck of the lion-eagle is short, the ears well developed, the mane figured by three wild locks. The talons are closing on the prey sideways as usual in Elam, and not in front as on the vase of Entemena. The two rampant animals are a species of goat-like antelope like the chamois. It is said that the berkout, the Oriental golden eagle, catches hare, fox, antelope, ibex, wolf, and boar.

The mountain bison with the red thick coat and short, round crescent horns still lives wild in the Caucasus. The urochs with diverging horns from which descend the modern tame cattle is today extinct. It has no beard or locks of hair and is a favourite motif, represented as rampant in a thicket of conventional plants in a landscape of hills. The big buds of the plants sometimes spread into star flowers.

The bull-man Enkidu holding up by the hind leg two leopards is a classical figure of the cycle of the heroic hunters. His counterpart is Gilgamesh holding two leopards by the tail. Eabani is in profile and wears a belt and the beard, locks, and horns of the man-headed bison. The twisted bodies and threatening heads of the enraged animals are remarkable. The strong heraldic symmetry is everywhere prevalent.

The lion attacking the bull is known from other examples which prove the strong school traditions of the Sumerian artist. The lion has stopped the onrushing bull, seized it round the neck, and is biting it in the shoulder. His head is turned full face. The mane is treated in the great, energetic style of Mesilim, back in the time of, if not before, the early kings of Kish.

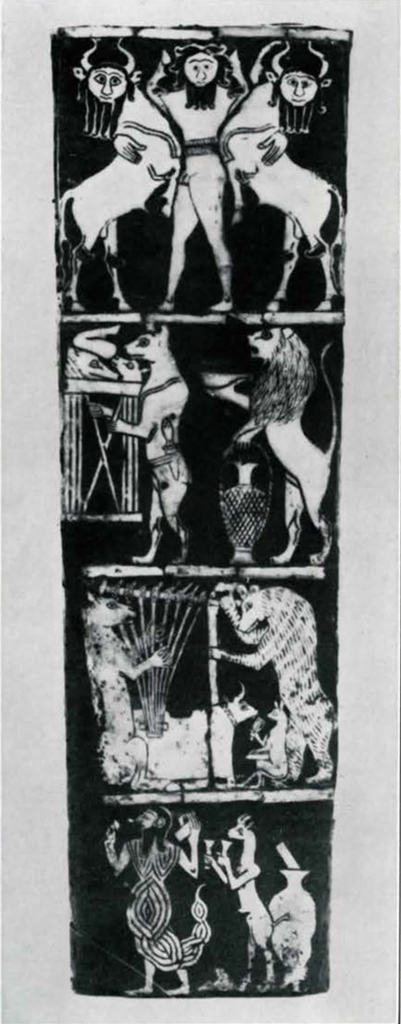

The Gold and Lapis Bull’s Head

This bull’s head in gold with a beard made of lapis is a magnificent example of the old Sumerian art of the same style as the calf’s head decorating the queen’s harp. It was probably part of another harp, buried in the grave of the unknown king. “A row of engraved shell plaques ornamented the front of the figure set between the legs just below the level of the beard.”

The beard transforms the bull into a legendary animal. The square muzzle regarded en face, the crescent horns with tips of lapis, the large open eyes with superciliary folds, and the quick flapping ears have a superior vigour. We almost expect to hear the bellowing voice.

But the greatest surprise is provided by the four engraved plaques below, unrivalled for the energy and beauty of the drawing, and their richness in mythological subjects. All betray a master hand and a strong Elamite influence, animals playing the parts of men, composite animals given human arms and faces, a scorpion-man, animal musicians of types unknown except on Elamite seal impressions. Gilgamesh en face protecting two man-headed bisons is a classical Sumerian model and the head of the scorpion-man seems to be a copy of the oldest inlaid figures from Kish. The lion rampant may have inspired the carving of the macehead of Mesilim or the engraving on the colossal copper lance from Lagash. But the beautifully shaped jar apparently protected by wickerwork has no parallel outside of Elam. The tracing of the figures is so precise and refined, sober with a gentle charm, that it suggests engraving not so much as painting, such as we expect on Greek vases. But the energetic drawing, the symmetry of subjects, the framing of each panel, and the mythological composition are purely Oriental and Sumerian. The surprise is to find such beautiful works of art at such an early date.

Let us go into details. Gilgamesh, the famous king of Uruk, would be today the perfect athlete. He is the desire of Ishtar, so strong that no wild animal, bull, leopard, or lion, can resist him. The Sumerian artists never tire of representing the hero in close contests with all kinds of rampant or fallen animals. The type of Gilgamesh in full face, with long locks on either side, and the long curls of an imposing beard carefully arranged below his chin, is comparatively recent and betrays a change in manners and school. Older figures of the glorious hunter show him in profile with wild locks and no beard. We know how fond the Sumerians were of soap and razor. Their completely shorn heads are always conspicuous. The beard hanging below clean shaven chin and lips may be an artificial ornament that would go far to explain the lapis beard of the golden bull. It was the current fashion for kings and gods at the time of Urnina and later as seen on the Stela of the Vultures. Wigs may have added a borrowed splendour to bald Sumerian heads, as evidenced by the gold wig of King Meskalamdug. Men with natural short hair and beard, generally servants, shepherds, butchers, masons, musicians, and hunters of the older Elamite type, are represented mingling with shaven Sumerians. We may suspect a mixing of races which must have existed very early in that country. The Sumerian soldiers and the king are all shorn, while their enemies—and some of the servants—have short hair and beard. The confusion begins with the long locks—evidently of a wig—with which they cover their heads even when at war and which make them look like women in the absence of a beard, false or not, or other signs of sex.8

Hair and beard of Gilgamesh may have been natural. Even in the days of wigs some men used to wear their own hair. But we are evidently on legendary ground, where the hairiness borrowed from kingly state would convey the superhuman strength and dignity of the semidivine hero. The Gilgamesh face with hair and beard is the product of a classical conventional school. The same face has been given to a composite monster famous to the end of the Assyrian empire: the man-headed bison. In exchange the bison’s horns placed on the head of a human king or queen will be a symbol of divinity.

Gilgamesh is nude except for the triple belt with which he has girded his loins.

The second panel represents an extraordinarily interesting ritual scene where the parts of the priest and of the assistant are played by animals. The butcher priest with his knife in his belt who carries the portable altar is a mastiff with a short tail, of the type found on Elamite seal impressions. There also he plays quaintly the part of a shepherd milking a goat from behind, assisted by a fox who holds the goat by beard and horns. The cane (?) altar with uprights reinforced by crosspieces, is of an unusual type not unlike an hour glass. On it are piled choice pieces, a leg of lamb, a calf’s head, and the head of a bear. The dog is given human hands and arms to carry the altar—the Gi-gab Sumerian altar. The knife is a copy of the gold dagger with the lapis handle and the rivets affect the same triangular shape.

The assistant lion is a splendid example of a rampant figure that would grace any coat of arms. The drawing of the old Sumerian artist has fixed forever a classical type rarely surpassed. The treatment of the mane, represented by a series of imbricated tufts of hair of triangular shape, has an archaic vigour also found on old Sumerian works of art, the mace of King Mesilim, the great copper lance of Lagash. The lion carries in his hands a lamp and a jar of wine. The lamp—some original examples in gold and silver have been found in the graves—has that peculiar form evolved from a sea shell, “out of conch cut in two so that the valve at the end might serve as a groove to support the wick.” The jar may have been painted, or more likely was protected by a network of fibre, like the modern Italian fiaschi. It was carried in the same way by a loop of cord attached to the basketwork. Jars of the same type, enigmatically connected with lions or leopards, with a graphic representation of the fiery liquid overflowing are found in the Elamite repertory of seal impressions. The leopard is the familiar animal of Bacchus. The wine instils into men’s hearts the courage of the lion. The mother of King Lemuel used to tell him:

“Give strong drink unto him that is ready to perish, and wine unto those that be of heavy heart.”

There is no ritual sacrifice without ritual music : the sound of the harp and the clanging of the cymbals. Animal musicians fill the next panels. A seated donkey plays on the harp upheld by a bear which one might swear was dancing, if its hands were not so firmly fixed on the frame of the harp. This is friendly and needful aid, since the donkey has both hands and ten extended fingers busy with the strings. The minute tracing of the fingers on either side of the cords is remarkable and in the best tradition of Sumerian art. The head of the donkey is a close study of nature, as are also the other animal figures. The curve of the back is well marked, outlined by the second upright of the harp, which looks like a false tress of hair. The strong strings spread fanlike from the sounding-box to the upper bar, to which they are attached by a double knot. They are eight in number. The slit in the sounding-box, just above the point where they are attached, makes it more resonant. We have seen that the bull’s head, here probably of gold and without beard, is part of the traditional decoration of the harp. Even the rest of the sounding-box affects to copy the body of a couchant bull. A band of inlay separates the metal head from the wood of the box.

The figure of the bear is very unusual, but its rough hair indicated by markings, its short tail and legs, the lump on the shoulders, and the whole bearish attitude of head and arms are very characteristic. No doubt we are to look to the neighbouring mountain land of Elam for its original home, as well as for that of the small animal sitting at its feet, shaking a rattle and drumming on a board. This animal is, as far as we can judge, more like an ichneumon than a monkey. Its connection with the bear and the donkey musicians would delight any folklorist. When first met on Elamite seal impressions it was described as an “unidentified feline species, often seated on its hind legs like a man. It has two small round ears and a sharp nose. Its tail is long and thin. It is represented playing with a small fox and holding it by the tail, catching flies, holding long streamers, or sitting in a boat, oar or harpoon in hand. This animal may be a giant ichneumon or a monkey.”9 A connection between foxes and musicians, or musicians with a fox’s tail, seems possible in certain Elamite seal impressions.

Finally the scorpion-man strutting in front of a rampant chamois is the most extraordinary figure of the set. Is he supposed to symbolize the wild spirit of the dance, his nipping claws transformed into human arms and hands, his long jointed tail ending in a curled up venomous sting above a pair of human feet, his head with the finely plaited hair and beard of the approved Kish style? The objects in his hands are unfortunately indistinct, but might be prehistoric castanets. Scorpions and tarantulas have always been thought to cause fabulous dancing diseases. The same wild spirit animates the rampant chamois, jumping like the “kids of Engadi.” What seem to be small tumblers in its hands are probably rattles or cymbals. The beautifully shaped high jar at the back with a rectangular piece—or pipe—set at an angle in the mouth probably gives the last touch to a complete picture of a feast with dance and music. Nothing so rich and full of importance for a study of old Sumerian art and history has ever before come out of the field. With the other objects found in the pre-dynastic graves at Ur, these beautiful masterpieces revolutionize our idea of Mesopotamian civilization in the fourth millennium B.C.

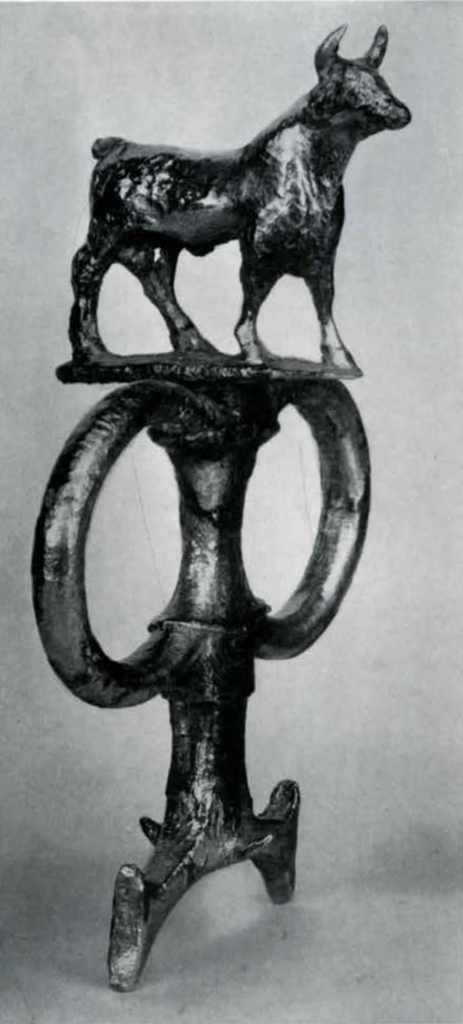

As part of a wholesale burial of guards, servants, wives, and singers, in a shaft round the grave of the king, were found two chariots with grooms and teams of oxen. ” Inside the shaft proper, standing as they had been backed down the slope came two wagons, clumsy four-wheeled affairs, each drawn by three oxen. Of the wooden wagon little was found, for wood cannot endure the soil of Ur. The oxen wore wide collars of silver decorated with patterns in repoussé work and had large silver rings in their nostrils. On the reins were strung beads of silver and lapis lazuli and they passed through rein-rings of silver surmounted by a mascot in the form of a bull.” The queen’s chariot had an electrum mascot in the shape of a donkey.10 A passant lion decorated the pole of the state chariot of Ningirsu, patron god of Lagash.

The Baghdad Museum has claimed as its share the bull mascot. It is a magnificent example of Sumerian art in modelling and casting. Animal figures have always been a favourite subject in Sumer. The wild bull on the glazed bricks of the Ishtar gate is the last beautiful copy of a classical model. The copper bull in the round from Al ‘Ubaid proves how early the Sumerian artist had fixed the characters of a type never surpassed. The short body, the powerful front legs and chest, the raised head and the perfect arc of the horns, the natural attitude of the brute arrested in his walk and full of irresistible strength in its immobility, are a monument to that far back ancestor the Sumerian artist, so close and dear to us for his technical skill, his creative power, and his cult of beauty.

1 Del. 16, p. 2.↪

2 P. B. S. 14, p. 13.↪

3 MUSEUM JOURNAL, June, 1927, p. 150.↪

4 MUSEUM JOURNAL, September. 1926, p. 258.↪

5 Cf. MUSEUM JOURNAL, June, 1927, p. 150.↪

6 MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, pp. 31-33. ↪

7 MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, pp. 11.-13.↪

8 MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1925, p. 40.↪

9 Del., t. XVI. p. 22.↪

10 MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, pp. 17, 21.↪