THE spearthrower is one of the most remarkable of the inventions of primitive man and for that reason has ever been of great interest to the anthropologist, to whom its history, distribution, and diverse forms reveal much concerning the psychology and racial relationships of its makers. In the older literature it was more often known as a “throwing-board” or “throwing-stick,” but as these terms denote a missile rather than an implement, in the last thirty years they have been abandoned in favour of the accepted modern term “spearthrower.”

The spearthrower was not only probably the most interesting, but apparently also one of the earliest inventions of primitive man, preceding even the bow and arrow. While the latter is not known from prehistoric Europe, the most ancient region known archaeologically, before the Neolithic period, the beginning of which is estimated at about ten thousand years ago, beautifully carved spearthrowers, made of antler and bone, are among the most characteristic objects of the Magdalenian epoch, the last period of the Paleolithic. France and Switzerland have supplied practically all the known examples.

Image Number: 12130

The age of the Magdalenian era is generally estimated at from about 15000 to 11000 B.C. (Archeologists give such estimates with considerable hesitation, for there are no accurate data on which to base them in terms of years, but human nature—and this includes the archeologist himself—insists on such approximations, so the expert must give them to the best of his ability, admitting that they may be incorrect by centuries or millenniums.) Since, however, primitive man the world over, so far as our knowledge goes, made his first implements of wood, a perishable substance which under the most favourable conditions could not be preserved for more than a very few thousands of years, archaeologists presume that the manufacture of implements of wood preceded by ages that of the first similar object made of some harder substance. It is reasonably safe to presume, then, that the spearthrower was first invented long before the period represented by the beautifully carved specimens of Magdalenian age, and possibly not long after the first use of the spear itself. Spear points made of bone first appear in the Aurignacian period at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic Age, possibly twenty-five thousand years ago, but how many millenniums before this spears with points hardened by fire, and possibly thrown by the spearthrower, were used, we can but guess. The spearthrower is, then, an implement of great age.

That the spearthrower should have preceded its more efficient cousin, the bow, is not surprising. Simple as it seems, the latter is a much more complex weapon than the spearthrower. Its invention and manufacture required the realization of the force of springy wood and the possibility of its application and control, and the choice of proper materials for bow and cord. The realization, on the other hand, that greater force, distance and penetrating power could be given to a spear, dart or javelin by lengthening the throwing arm, must have occurred to an undersized warrior soon after first being outranged by a taller opponent. The proof of this is to be found in the Antipodes, the world’s uttermost outpost from an ethnological standpoint, where we find an epitome and a recapitulation of the early history of spearthrower and bow. In New Guinea the Papuans, people of relatively low culture, use both the spearthrower and the bow and arrow. The knowledge of the bow has reached Northern Australia, just across Torres Straits from New Guinea, but throughout the rest of that immense island the degraded, or rather extremely backward, Australians use the spear-thrower but are ignorant of the bow, while in that Ultima Thule of the world, Tasmania, the now extinct inhabitants who were practically in the Palaeolithic Age in the nineteenth century, knew neither bow nor spearthrower.

The spearthrower may be described as a device for lengthening the arm in order that it may give greater speed, and consequently greater distance and penetrating power, to the thrown spear, by means of the greater distance through which the propulsive power could be applied. Thus a man whose arm could be applied to the spear throughout an arc of eight feet—advancing, as is usual, one step during the throw—could, by the use of an ordinary spear-thrower, increase this arc to eleven feet. It is claimed that the additional power thus derived increases the speed of the spear several times, so that surprising distances may be achieved by its use.

The spearthrower possesses several other advantages over the bow, so that it remained, and even still remains, one of the principal arms of certain peoples rather high in the cultural scale who also possess bows and other more complex weapons. The spearthrower requires but one hand for its manipulation, while the bow and arrow require both hands. The former is therefore better adapted to hunting from boats, especially if the shooting must be done from a seated position. This explains the persistence of the weapon among such relatively highly specialized groups as the Eskimo. For similar reasons it was much employed by the two great empires of aboriginal America, the Peruvians, and the Aztecs of Mexico. Their armies, fighting in masses in more or less open country, used the spearthrower extensively, the left arm probably being employed to hold the shield.

The spearthrower is known from many parts of the world, from prehistoric France, from Melanesia and from Australia as has been mentioned, from Micronesia, from northeastern Asia and from several parts of America. We shall limit our present discussion to the latter region.

Since the spearthrower is obviously an invention of great age in Europe and is found in scattered localities throughout the world, as well as in several widely separated portions of America and among the relics of its oldest populations, it is generally believed that it was not an independent invention in America but was one of the weapons possessed by the original immigrants to America. These, it is believed, were about on the cultural level of the Magdalenian period and probably entered America at about that time.

In America the spearthrower is used at present in only three regions, widely separated. The Eskimo, throughout their vast extent from Alaska to Greenland and Labrador, still employ it as one of their most efficient weapons, certain of the tribes of the Amazon forests still manufacture and use it, and in Mexico, the modern Tarascan Indians of certain villages on the shores of Lake Patzcuaro in Michoacan, though comparatively civilized in most of their life and customs, still employ it in hunting wild fowl from their dugout boats.

In former days, however, the use of the spearthrower was much more widespread. As we have seen, it is probable that, at the time of the first occupation of America, it was universally employed by the slightly differentiated tribes of low culture who covered the land, but no specimens from this period exist, and the belief is pure theory. Specimens have been discovered, however, from the pre-Cliff-Dweller remains of Utah and the surrounding regions, made by the very early people known as the Basket Makers; from remains of uncertain, though undoubtedly pre-Columbian, age in Florida; from pre-Columbian graves on the coast of Peru and in Ecuador and Colombia; and from the Aztecs of the time of Montezuma and Cortes. The predecessors of the Aztecs, the Toltecs, also employed the spearthrower, as did the Haitians at the time of Columbus, and certain Californian Indians of a century and a half ago. These regions are represented by only from one to thirty known specimens each, all therefore of great value and rarity. The MUSEUM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA possesses some of the rarest and most famous of these, which, together with several more specimens of exceptional interest recently secured and heretofore undescribed, form the topic of the present article.

A Spearthrower from the Ancient Eskimo Thule Culture

In 1919 W. B. Van Valin was collecting material from the present and past Eskimo in the region of Point Barrow, the northernmost cape of Alaska. One of his Eskimo helpers one day discovered some human bones protruding from a mound of earth. Investigation revealed that a group of mounds in the immediate neighbourhood which had always been considered by the natives as of natural origin were in fact the remains of ancient houses which had fallen in. The modern Eskimo had no knowledge or tradition of any village at that place and it was evident that the site was of considerable age. Excavation revealed, even to unscientifically trained eyes, marked differences between the contents of the houses and those of the present Eskimo. To mention a few points, no tobacco pipes or evidence of the use of tobacco were found, no nets for fishing or sealing, and no labrets, the ornamental plugs inserted through the lips, which are universally worn by Alaskan Eskimo men at the present time. It is interesting to note that, upon other grounds, it has long been believed that the use of tobacco and of nets is of recent adoption among the Eskimo, Van Valin’s discovery being corroborative of this theory. The skeletal remains, of which a large and valuable series was recovered, were recently measured by Dr. Ales Hrdlicka of the United States National Museum in Washington, who found that they represent a type rather different from that of the modern Alaskan Eskimo and identical with the Eskimo of Greenland and Labrador. In explanation of this interesting and important discovery it is suggested that the present rather variant type of the Alaskan Eskimo may be due to his mixture with the more broadheaded Indian of the interior, and that before such mixture took place, at the time of the building of these old houses, the Eskimo physical type was homogeneous from Alaska to Labrador.

The artefacts found in these houses are typical of one phase of what is known as the Thule Culture, the ancient Eskimo culture which, in a relatively homogeneous form somewhat different from that of today, extended throughout practically the entire Eskimo area, at least from Greenland to Bering Strait. In the eastern Arctic the age of this culture is estimated at from about 500 to 1500 A.D. These estimates are based upon changes in sea level, but the same observations do not apply to Alaska. The Thule Culture there is of less certain age, but is probably of practically the same period as that of the eastern area.

Prominent among the artefacts from one of these houses was a wooden spearthrower of unusual type and excellent workmanship. It is difficult to believe that it could have been covered with damp soil even for a decade, not to say many centuries, yet in soil that is permanently frozen and never thawed, organic products will be preserved practically eternally. This has been shown by the discoveries of remains of mammoths with hide and hair intact in frozen tundras of Siberia.

The spearthrower is one of the most typical and characteristic of Eskimo implements. Although the culture of the Eskimo is relatively quite high and they possess numerous most efficient inventions, many more than most Indian tribes, yet they have retained the spearthrower and still make great use of it, mainly because of the ease with which the harpoon can be cast with one hand from their light skin boats or kayaks in spite of numb, gloved hands. The Eskimo spearthrower exists in many different types, each one characteristic of a definite locality. These forms have been studied and classified, so that it is possible to determine, with reasonable certainty, the district where any Eskimo spear-thrower was made.

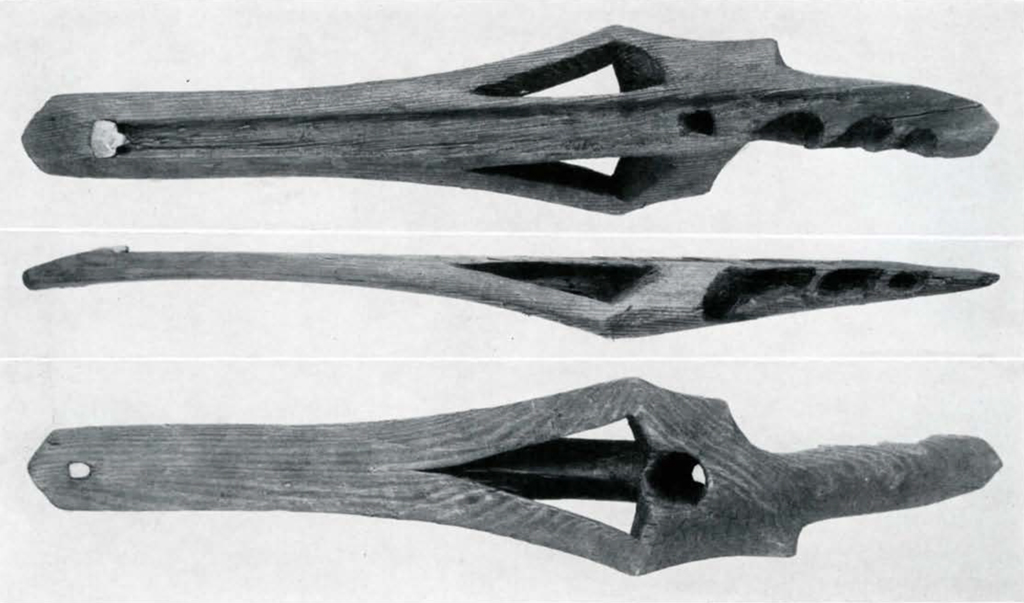

The Eskimo Thule Culture spearthrower illustrated on page 291 is very different from any of the modern types and, what is more surprising, is of superior grade from technical, utilitarian, and aesthetic points of view.

The Eskimo Thule Culture has been carefully investigated only within the last few years. The fullest report upon it1 states that the Eskimo of that time employed spearthrowers and records the discovery of one complete and one fragmentary specimen. The former is, however, “merely a flat wooden board, 38 cm. long, . . . of a rather primitive type; . . . in the rear end is the one edge slightly incurved for the hand ; in the fore-end a large hole for the peg and a smaller one.” Found in a site on Repulse Bay near the upper end of Hudson Bay, it resembles to some extent the spear-throwers of this region today, indicating that specialization had commenced even in those early times. It apparently lacks, however, the hole for the index finger which is now characteristic of every type from Greenland and Labrador to Bering Strait.

The old Point Barrow specimen, on the other hand, conforms to the general type of northern Alaskan spearthrowers, having a hole for the index finger on the medial line and grooves for the other three fingers on the edge. The spearthrower which most resembles it is one in the National Museum at Washington which was secured in “Russian America” in 1867 by Commodore John Rodgers and which, since its exact provenience is unknown, is therefore termed the “Rodgers type” by Otis T. Mason in his report on the throwing-sticks in the National Museum.2 Because of its points in common with present northern Alaskan spearthrowers, Mason put it in that classification, comparing it most closely to the spearthrowers from Kotzebue Sound, the great bay between Point Barrow and Bering Strait. Of this specimen Mason says, “The whole execution of this specimen is so much superior to that of any other in the Museum and the material so different as to create the suspicion that it was made by a white man, with steel tools.” It is shown upon page 293. The specimen in the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM is of a type superior even to this and of excellent execution, though the wood is beginning to show the appearance and wear of age.

We may therefore consider our specimen as the finest of the three known complete examples of the spearthrowers of the ancient Eskimo who belonged to the Thule Culture, and as the type specimen of its kind.

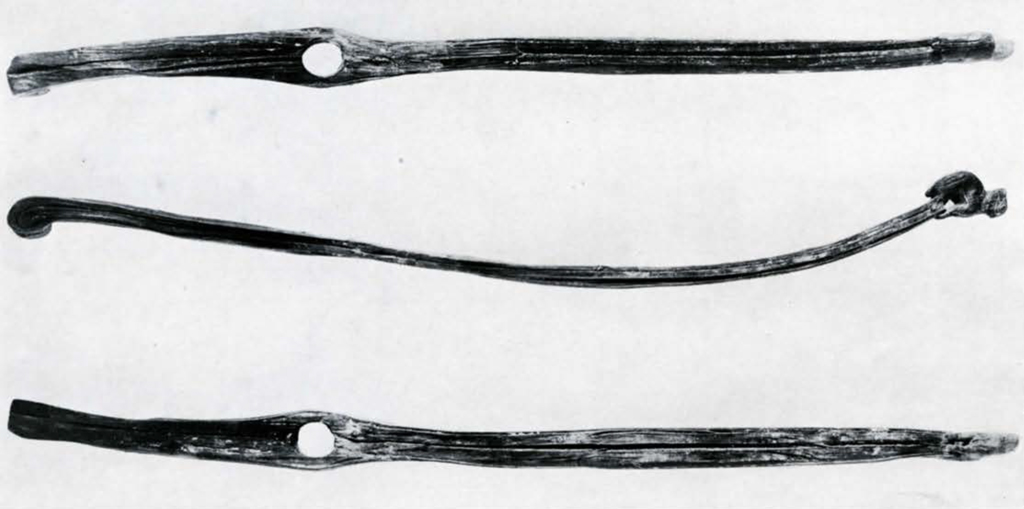

Image Number: 12131, 13275

The spearthrower is made of a coniferous wood and probably from a log which drifted down the Mackenzie River from the great forests of northern Canada. It measures 14½ inches in length and 2¾ inches in maximum width. The Mathiassen specimen measures 15 inches (38 cm.) in length and the ” Rodgers type ” specimen 19 inches. The form is not only graceful and artistic but eminently utilitarian and of technical excellence. Its peculiar characteristic, seen on no other Eskimo or Thule specimen, is near the central point where it widens and rises to an angle with lateral and vertical facets. Here the interior is hollowed out in such a way as to leave three rather thin shafts, a main, straight shaft on the upper side, braced by two curving buttress shafts on the lower side. In spear-throwers, the side on which the spear rests and which is held uppermost when in the act of casting it is termed the upper side; it would ordinarily be considered the lower side by the casual observer. The main shaft is of triangular cross-section, the broader side, grooved for the spear, being about an inch in width. The supporting buttresses are of trapezoidal cross-section. This removal of the wood not only adds to the beauty of the specimen, but reduces the weight of the implement without sacrificing strength at the point of greatest strain. This is the principal point in which it differs from the Rodgers spearthrower which is of practically even width throughout. The latter has, however, what is either a prototype or a debased form of this feature in a small carving on the lower side which Mason interprets as “the legs and feet of some animal carved out in a graceful manner.” The photograph seems to show the hind flippers of a seal.

In the anterior part the implement is symmetrical, the straight main shaft and the two curving bracing shafts coalescing into a shaft of an inch and a quarter in width and three-eighths of an inch in thickness. The point is curved slightly downwards. The groove for the spear is about an eighth of an inch in depth and widens from half an inch at the anterior end to three-quarters at the posterior. The groove ends at the anterior or distal terminus with an ivory peg having a blunt short conical point which fitted into the butt of the spear. This peg is very firmly set into the wood; although apparently only a small peg and lightly fastened, it possesses a tenon which runs through the wood to the lower side where it is cut off flush with the surface. The direction of this tenon opposes the line of stress so that it can resist great strain.

The posterior part of the spearthrower is somewhat, though not markedly, asymmetrical, being ingeniously and perfectly adapted to fit the hand, the right hand in this case. In the medial line on the lower side a deep depression is made for the index finger. This depression extends backwards to hold the flexed finger in the strongest position, and perforates the opposite side, in the centre of the spear-groove, in a small hole. It is doubtful if this orifice was intentional since it serves no purpose and might interfere with the easy rest of the spear in the groove. More likely the finger orifice was hollowed out too far, or possibly the orifice was worn through by the fingernail after long use. The same feature, however, was noted on the Rodgers spearthrower.

The rest of the handle is made to fit the thumb and the other three fingers. The part which is gripped is small and slightly eccentric, but the spear-groove on the upper side is continued to the very end, thus differing markedly from the Rodgers specimen in which the shallow groove does not extend even to the hole for the index finger. The two lateral edges are notched at different distances to fit the thumb on one side and the middle finger on the other. On the upper side three deep notches of a size and shape to fit perfectly the three fingers are carved into the wood. These notches are sunk into the groove for the spear, so that it is evident that the fingers could have had no part in holding the spear which apparently lay against or over the finger tips. It was evidently held in place by means of the thumb alone.

Image Number: 12131, 13275

Some Spearthrowers of the Basket Makers of Utah

In the arid regions of the American Southwest much intensive work has been done in archaeology, so that today we have a clearer knowledge of the sequence of cultures and of the movements of peoples here than anywhere else in America. Many periods are distinguished, based mainly on types of pottery, extending from the modern and recent Pueblo Indians, through the Cliff Dwellers back to most ancient times. At the beginning of the series stand the so-called Basket Makers of southern Utah and northern Arizona, the earliest sedentary agricultural people of the Southwest of which we have any knowledge. Even this knowledge is very slight and is limited to what we can learn from the objects which they left in their burial caves, for they apparently built no houses which have lasted. They practised agriculture but also did more hunting than their successors, since they were probably the first people in that region to change from a hunting to an agricultural plane of life. Their distinguishing characteristics, however, were their ignorance, or practical ignorance, of pottery, and the manufacture and use of excellent baskets instead, much resembling those of California at present. It is from this characteristic that their name is derived.

One of the characteristic implements of the Basket Makers was the wooden spearthrower which they apparently employed to the exclusion of the bow and arrow. The first spearthrower brought from this region attracted the greatest interest, since it was the first discovery of a spearthrower east of the Pacific, north of Mexico, and south of the Arctic. Several of these spearthrowers were brought out by professional nonscientific excavators before the culture of the Basket Makers was recognized as a separate entity, and thus they became one of the diagnostic characteristics of the culture.

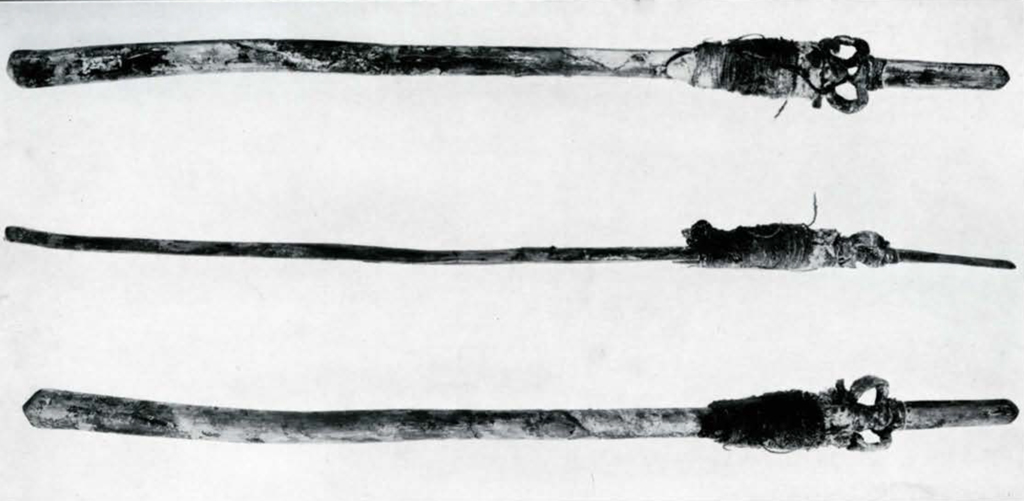

In 1893 one of the great American anthropologists of the last generation, the late Otis T. Mason of the National Museum, was inspecting the archeological exhibit of the State of Colorado at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. His enthusiasm was awakened by the sight of several implements which his professional eye identified as spearthrowers. They were the first of these implements known from the interior of North America and the enthusiastic scientist at once wrote a note to Science3 calling the attention of the archeological world to his discovery. Probably thousands of persons before him had gazed over the collection, but none had realized the importance of the peculiar implements, which were described in the catalogue as “magic wands.” Such terms as “magic wand” and “ceremonial object” are havens of security for the amateur archaeologist—and often for the professional as well—who can consign any puzzling what-is-it to these capacious omnium gatherums. The collection was probably made by the four famous Wetherill brothers and C. C. Mason (the third of this ubiquitous name to be concerned in this article), and presumably in Mancos Canyon, Colorado. The late George H. Pepper, however, in his article on The Throwing-stick of a Prehistoric People of the Southwest,4 avows his certainty that it must have come from the region of Grand Gulch, Utah. After the World’s Columbian Exposition these collections, which were or became a part of the Hazzard Collection, were secured by this MUSEUM.

“In the Hazzard Collection in the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania there is perhaps the best series of throwing-stick material available,” wrote Pepper; and again, “The most noted throwing-stick from the Southwest is in the Hazzard Collection; it is the first one known from that region.”

This famous spearthrower is of further interest in connection with an incident which demonstrates the remarkable knowledge of another of the leaders of anthropological science of a generation ago. The late Frank Hamilton Cushing of the Bureau of American Ethnology at Washington, because of his unexcelled knowledge of the Pueblo Indians, the modern descendants, from a cultural point of view at least, of the Basket Makers, was apparently asked by the then curator of the MUSEUM, Stewart Culin, to prepare the labels for the Hazzard Collection when it was placed on exhibition. His label reads, ” Throwing stick of flexible walnut (?) sapling, showing wild cat tooth fastening of finger-loops with ‘ feather cleaver’ or ‘lightening stone’ (knife or arrow of chalcedony), war fetich stone ‘blood-clot ‘ of limonite and wrapping of dyed cotton yarn, originally decorated with bright feather work.”

The elements to which Cushing refers are easily seen in the illustration on page 297, but whether his interpretation of them is correct can never be known with certainty. That it probably is is indicated by this most interesting incident which shows not only Cushing’s remarkable knowledge of Southwestern ceremonialism—he was adopted into the Macaw clan of the Zuni tribe and lived five consecutive years among them, becoming second chief of the tribe and Head Priest of the Bow—but also the extreme age and conservatism of ceremonial concepts in that region.

Cushing expressed to Culin his opinion ” that a piece of turquoise, explained by him as the heart of a fetishish (sic) bird, was concealed beneath the heavy wrapping of brown yarn that binds the finger loops of the prehistoric throwingstick from Mañas5 Cañon, Colorado, in the University Museum.” This is recounted by Culin in a short article entitled “An Archaeological Application of the Röntgen Rays,”6 in an early publication of this MUSEUM. X-rays had at that time just become perfected for medical purposes and Culin conceived the idea of confirming Cushing’s hypothesis by this means. Radiographs7 revealed four beads, presumably of turquoise, under the wrapping. “I may add,” says Culin, ” that the extreme fragility of the wrapping is such as to render an examination by other means impossible without serious injury to this valuable object.” The present writer quite agrees with Culin on this point.

This spearthrower measures twenty-five inches in length and is apparently made of a split sapling which varies from three-quarters to one inch in width, the greater width being at the anterior or distal end. It is curved laterally to a slight degree, but this is probably unintentional and due to warping, although in some regions, such as Australia, spearthrowers with a pronounced intentional lateral curvature are found. The lower side retains the natural semi-circularity of the twig, the upper half being relatively flat with a very shallow groove in the medial line for the spear. The notch in which the end of the spear rested consists of a rectangular excavation about an inch long, three-eighths of an inch wide and one-eighth deep, the farther side of which is extended out in a spur. The spearthrower was apparently originally wrapped with a strip of hide wound around it in a spiral, traces of which still remain.

The handle or proximal end is of greatest interest on account of the ceremonial objects placed there. Nearest the end are twin finger-loops made of rawhide, now much shrunken and distorted from their original shape. These were, when the implement was in use, occupied by the index and middle fingers which were thrust in from the lower side, while the thumb and the other two fingers grasped the centre of the spear as it lay along the groove of the spearthrower. Caught under the rawhide wrapping of the loop is a tooth of a canine or feline animal. The main part of the wrapping, which probably had no utilitarian but only an aesthetic and ceremonial importance, is found immediately beyond the finger-loops and is three inches in length and from an inch to an inch and a half in thickness. The under part apparently consists of a wrapping of brown yucca fiber, the upper part of cotton yarn, now of a uniform brown tint, but possibly once of brighter colours. All traces of the “bright feather work” reported by Cushing, if they ever existed, have now disappeared, but the proximal part, near the finger-loops, is covered by traces of a yellowish brown fur. Completely hidden by the wrapping on the lower side of the implement are the four beads discovered by X-rays which, according to Cushing, are probably of turquoise and represent the heart of a fetish bird. Projecting beyond the end of the wrapping is the bit of black shiny limonite concretion interpreted by Cushing as a “war fetich stone blood clot,’ ” and in a similar position on the opposite or upper side is the end of a beautiful thin blade of chipped and polished chalcedony. This is, or was, as Cushing states, either a knife-blade or an arrowhead, but his interpretation of it as a “feather cleaver” or “lightening stone” must be taken on his ipse dixit.

In the Hazzard Collection there is also the handle of another spearthrower, better preserved than that of the complete specimen, but containing no ceremonial objects. It is shown on page 299. Cushing’s old label for this reads, “Handle of throwing-stick of live oak sapling, bared of wrapping, but with perfect finger-loops, and with rattlesnake skin fetich.” The shaft of this is narrower and straighter than that of the preceding specimen, the width being about eleven-sixteenths of an inch. At the proximal point and on either side of the finger-loops are wrappings of sinew. The finger-loops are made of some rigid material covered with tanned buckskin, and are intended for small fingers. The small hands and feet of even tall American Indians are matters of record, and the sedentary agricultural natives of the Pueblos of Arizona and New Mexico are among the shortest members of their race.

Around the shaft between the loops are several turns of narrow, thin, hard hide which may be rattlesnake skin, but I am inclined to believe that the feature thus referred to by Cushing is the short strip which extends between the loops parallel to the main shaft and on the lower side of it. This, although superficially resembling snakeskin, is composed of braided leather thongs. With all his deep insight and thorough knowledge, Cushing apparently made a hasty and incorrect identification in this case.

“The largest and heaviest dart-thrower from the Southwest that has been noted”8 is also in this MUSEUM. This, No. 22736, was purchased at St. Michaels, Arizona, in 1902, and is said to have been found at Lukachukai, Arizona. This small place is probably in the Basket Maker region, to which culture the spearthrower doubtless belongs. It is, however, rather different from those mentioned above, and is of superior workmanship and technique, as may be seen from the illustration on page 299. In length it measures twenty-three and three-quarters inches, in thickness from a quarter to three-eighths of an inch and in width from seven-eighths to one and one-quarter inches, the size increasing steadily from proximal to distal end. It is therefore of relatively flat cross-section, the upper and lower faces very slightly, the edges markedly, convex. It is perfectly straight and smooth, being carved from a large piece of reddish wood such as oak or hickory, not split from a sapling as in the other cases. A slight sigmoid curve, doubtless intentional, in the plane of the weapon gives it a most efficient shape.

Close to the proximal end each edge is indented in a broad notch three-sixteenths of an inch deep, thus reducing the width at this point from fifteen-sixteenths to nine-sixteenths of an inch. This was obviously done to provide a finger-hold; although the appearance of the specimen is somewhat improved thereby, it produces a point of weakness. Not a trace of finger-loops or binding at this point can be seen and one might conjecture that the notches alone were used for the finger-grip were it not that the black surface layer, resulting from the grip of the sweaty, oily, dirty palms of the hunter as he followed the antelope over the hot, dusty Arizona plateau, stops at a sharp line and the region of the notches is clear and clean. This indicates that they were originally covered with wrapping or binding, and we may confidently conclude that this wrapping bound on finger-loops of a type similar to those of the other spearthrowers from the same region.

The lower side of the implement is perfectly plain and presents no details of interest except at the distal point where, in the medial line, two holes have been drilled to meet in the interior of the woo in an elbow angle. Possibly this was intended for the insertion of a cord for hanging up the weapon when not in use, or possibly for the attachment of an ornament, such as a feather.

The upper side is slightly ornamented. Along each edge from the finger notches to the distal point runs a straight incised line, certainly purely ornamental in purpose. At the distal point the thickness is greatly increased in the medial line to produce the spur on whose point the spear rests. This spur is an inch and three-quarters long and five-sixteenths of an inch broad, and consists merely of a raised ridge, one end of which extends to the distal end of the implement where it increases the thickness to five-eighths of an inch; the anterior end is slightly undercut to form a projecting point. From under this point a shallow groove extends along the medial line of the weapon to accommodate the resting spear. It measures three-eighths of an inch in width and five inches in length. From its anterior terminus spring two short divergent incised lines, which are probably purely decorative in purpose.

Two Spearthrowers from the Coast of Florida

Quite unique, and certainly the rarest spearthrowers known from America, are several now in the UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM which were taken in 1896 from the mud and muck of Key Marco on the Gulf Coast of Florida. The expedition which secured them, a joint project of this MUSEUM and the Bureau of American Ethnology of Washington, under the leadership of the late Frank Hamilton Cushing, who was mentioned in connection with the Basket Maker spearthrowers, made some extremely important contributions to our knowledge of American archaeology. The results of the expedition have been widely quoted in archeological literature. The culture found there differed in many respects from that characteristic of the peoples of the Florida mainland, and in some respects resembled that of the inhabitants of the Antilles and even of South America. Especially unusual and interesting were the wooden objects which, strange as it may seem, can be preserved indefinitely only under two exactly opposite natural conditions, that of complete and constant aridity, and that of similar saturation. Those preserved under the latter conditions, however, generally warp and twist sadly, or even disintegrate completely on exposure to air. Such has been the fate of many of the strange and remarkable wooden specimens brought from the Florida mud. Fortunately, the expedition enjoyed the services of an artist and photographer who made careful copies of the unique objects, many of them shining with bright colours, as they were carefully drawn from the mud where they had reposed for centuries. Unfortunately, however, the full report of this work has never been published, for Cushing died in 1900 while engaged in working upon it, and archaeologists have had to content themselves with a preliminary report, although a fairly full one, made by him in 1896.9

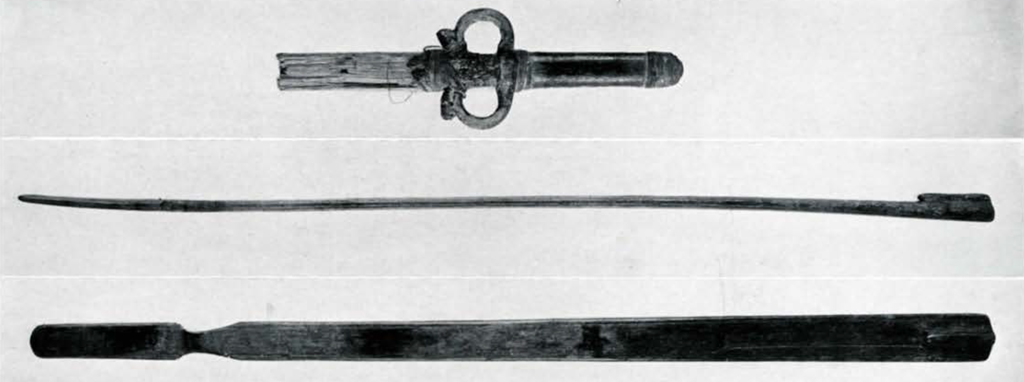

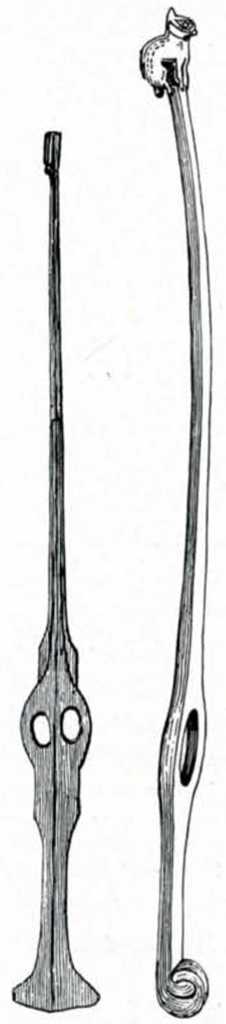

Image Number: 20125

Among these rare wooden objects are several spearthrowers of remarkable and unusual types. Unique of their kind, they are the only ones known north of Mexico, south of Labrador, and east of Arkansas. “It was significant,” says Cushing, “that no bows were discovered in any portion of the court, but of atlatls or throwing sticks, both fragmentary and entire, four or five examples were found. Two of the most perfect of these were also the most characteristic, since one was double-holed, the other single-holed.” The absence of bows is not surprising, since we have seen that they were not employed by the Basket Makers either. It must not be assumed, however, that the Florida Key Dwellers were contemporaries of the Basket Makers; they may have been, but more likely were more recent. It seems that, although the spearthrower is older, and normally a less efficient weapon than the bow, the former is or was the preferred weapon and employed to the exclusion of the bow even among some recent peoples of relatively high culture surrounded by other groups who preferred the bow. Numbers of arrows were found by Cushing and his helpers, however, but the line of distinction between a spear and an arrow is a vague one; these arrows may have been light darts thrown by the spearthrower or actual arrows propelled by bows, the non-discovery of the latter being accidental.

The two complete spearthrowers, drawings of which, taken from Cushing’s original report, are reproduced on the next page, are very different from any which we have hitherto considered. They are extremely slender and graceful and the wood must have been of unusual strength and resilience, if indeed the specimens were not purely ceremonial and not intended for actual use. Lateral finger-loops such as are characteristic of the Basket Maker and the Aztec spearthrowers are not used and the specimens are longer and much more slender than, and of a different shape from, the Eskimo, Californian and Tarascan implements which have the fingerholes perforated in the wood. No types resembling at all closely the Florida specimens are known, but the closest approximation to them seems to be found among the spearthrowers of certain tribes of eastern Colombia, who use long slender implements of artistic appearance of hard red wood.

The double-holed spearthrower, according to Cushing’s description, is made of a dark, red-brown, flexible wood and measures sixteen10 inches in length. His description of it folows. “The first was some eighteen inches in length, delicate, slender, slightly curved and originally, quite springy. It was fitted with a short spur at the smaller end and was unequally spread or flanged at the larger or grasping end. The shaft-groove terminated in an ornamental device, whence a slighter crease led quite to the end of the handle, and the whole implement was delicately carved and engraved with edge-lines and when first taken from the muck exhibited a high polish and beautiful rosewood color.”

The second was even finer. Cushing describes it as “somewhat longer, slightly thicker, wider shafted, more curved, and, as I have said before, furnished with only a single fingerhole. At the smaller end was a diminutive but very perfect carving of a rabbit, in the act of thumping, so placed that his erect tail formed the propelling-spur. This instrument was also fitted with a short shaft-groove and was carved and decorated with edge and side lines, and the handle end was beautifully curved down and rounded so as to form a volute or rolled knob…. Its length was nineteen inches, and it was made from fine, springy hard wood- like rose wood in appearance- probably the heart portion of the so-called ironwood of the region.”

The carved rabbit at the distal end with its tail forming the spur is strongly reminiscent of the prehistoric spearthrowers of France which were almost uniformly carved in animal forms; here also in a number of the best examples, the tail formed the spur. There can hardly be any historical connection between the two regions, and the tail spur is probably purely coincidental, but the frequent use of carved animals on the implements may readily be explained upon grounds of sympathetic magic—the carved animal upon the weapon would exert a magical influence over its living kin in the hunt.

The condition of the two spearthrowers today may be seen on pages 301 and 304. The longer and finer specimen has not deteriorated greatly, although the curvature has been much accentuated, the single fingerhole has shrunk slightly, and the length has shrunk from nineteen to seventeen and three-quarters inches. The smaller and lighter double-holed spearthrower has suffered much more seri-ously. It now measures fifteen instead of the sixteen or eighteen inches originally recorded, and is much warped and twisted, the wood being extremely light and flexible. The twin fingerholes have shrunk so that they would no more than accommodate one finger were the septum between them removed, the diameter of the double opening being now only three-quarters of an inch. The spur at the distal end has warped to one side so that it now lies on the plane of the broader handle.

The wood of both is hard, firm, unusually flexible and at present of a dark brown colour, approaching black. Both are decorated on all four faces with a shallow, thin, straight medial groove extending the length of the implement, and with parallel marginal grooves close to the edges of the broader sides. Between the fingerholes of the smaller specimen there is a high ridge and the spur is formed by increasing the width at the distal point for a distance of an inch and a half, and undercutting to produce a knob of sugarloaf shape.

The single-holed spearthrower is of superior workmanship and decoration. The broad groove for the reception of the spear on the upper side ends some three inches short of the fingerhole where it is replaced by a slight ridge, the transition being marked by a transverse groove of chevron shape. On both sides the medial groove bifurcates on approaching the fingerhole. The two ends of this specimen are the points of greatest interest. The handle terminus ends in a graceful volute knob like that of a violin, which probably prevented the grasp from slipping down too far. At the distal point the daintily carved animal, shown on page 307, is an admirable bit of woodcarving. While perfectly symmetrical, it is also perfectly naturalistic. It is most probably, as Cushing identifies it, ” a rabbit in the act of thumping,” but the present damage to the ears and nose has destroyed some of the characteristic features. The cramped posture of the animal, clinging to the narrow end of the implement, is admirable and indicates an excellent knowledge of animal anatomy. The spaces between the forelegs and between the fore and hindlegs are hollowed out and the legs themselves are perfectly shaped, the forelegs resting on the lower side of the spearthrower, the hindlegs grasping the edges. Even the toes are carefully portrayed, the grooves separating them being about half a millimeter apart. The entire dainty figure is only an inch and a half high, an inch long and half an inch wide. The incised details of the face are slightly conventionalized but decidedly rabbitlike. The stumpy tail forms the spur for the end of the spear, the longitudinal groove at this point being deepened and widened.

The discovery of these two spearthrowers on the Florida Coast was a scientific item of considerable importance, bearing on the moot question of pre-Columbian influences between Florida and the West Indies. The culture of the Antilles was South American at bottom and both of the races which inhabited the islands, the Insular Arawak or Tainan, who were the earlier population, and the invading Carib, were members of groups widely spread in South America. The latter, at the time of Columbus, were engaged in conquering the islands, having possessed themselves of the Lesser Antilles, from which point they were attacking the Arawak in the larger western islands.

Columbus and other contemporary discoverers report that while the Carib in the east used bows and arrows, the Arawak of Cuba and Haiti knew only the spearthrower. This is another evidence of the priority of the spearthrower in human history. Moreover, the short distance between Cuba and the Bahamas and the coast of Florida suggests that our Florida spearthrowers are probably more closely related to the prehistoric forms of the Antilles, and through them to those of South America, than to those of the Eskimo, the Basket Makers, or the Aztecs.

The spearthrowers, it may be remarked, present only one of several phases in which the culture of Cushing’s Florida finds shows resemblances with Antillean-South American cultures, and these discoveries form one of the most potent arguments in favour of such Antillean influences in the southeastern American states. The consensus of scientific opinion upon this question is that the influence of the Antilles upon our southeastern states was evident in places, but not great.

Ancient Spearthrowers from the Coast of Peru

The MUSEUM unfortunately possesses no example of the beautiful spearthrowers or atlatls of the ancient Aztecs, elaborately carved, gilded and sometimes inlaid with mosaics. These extraordinary objects are exceedingly rare and were probably either exclusively ceremonial in purpose or owned by the highest dignitaries. It is owing to their magnificence alone that they have been preserved, for we know not one example of the ordinary type of spearthrower carried by the common warrior, of the propulsive power of which the conquistadores spoke with so much respect. The predecessors of the Aztecs, the Toltecs, also used a spearthrower, which is depicted upon the reliefs at Chichen Itza, Yucatan, where Toltec warriors are shown carrying spears and spearthrowers, as may be seen in the illustration on page 308. The latter are portrayed as much shorter than the known Aztec weapons and, apparently, as decorated with plumes.

On Lake Patzcuaro in the state of Michoacan, Mexico, the Tarascan Indians of certain villages along the shore still employ the spearthrower in hunting wild fowl. There are some of these implements in the collections of the MUSEUM, but they are of slight interest, being made of one piece of wood, plain and undecorated, with double fingerholes. The illustration on page 313, made by Frederick Starr, late Professor of Anthropology at the University of Chicago,11 shows how it was employed.

It is quite likely that at one time the spearthrower was used throughout the region of intensive agriculture from Arizona to Chile. But most of this region is very humid and wooden objects perish quickly. In some places hook-shaped stones which are presumed to have been the knob spurs of spearthrowers have been found. This is especially true of Ecuador and Colombia where so many of these small stones of such characteristic shapes have been found that it is generally agreed that they represent these spurs. The spearthrower is used today by some of the Indian tribes in Brazil, especially by those on the Araguaya and Xingu rivers.

The most perfectly preserved examples of spearthrowers must naturally be sought in the region of greatest aridity. In America this is the Pacific coast of Peru and Chile. Rains in this region are exceedingly rare, the country in general consisting of the barest desert broken now and then by the fertile valleys of rivers descending from the snow-capped summits of the Andes. In Trujillo, for instance, which is near the northern limit of the arid area and is by no means the driest spot, the average yearly rainfall from 1918 to 1924 was 4 millimetres, about an eighth of an inch. However, in 1925, owing to a strange deflection of the cold Humboldt Current along the coast, torrential rains, an unheard-of thing, occurred; 290 millimetres of rain, practically twelve inches, fell in three days in March, with a total for the season of 300 to 400 millimetres. The unprecedented torrents naturally caused great suffering and tremendous damage not only to the works of modern man but to the remains of his predecessors, some of which were damaged more in those three days than in the preceding millennium.

This region, indeed, is in many respects the American counterpart of Egypt. Not only was the culture very high and the artefacts of the greatest interest and beauty, but the custom of the inhabitants, who occupied the fertile river valleys, of burying the possessions of the deceased with them in the arid deserts has preserved for us many unique objects which afford us a clear impression of the material aspects of their culture.

The objects found in these coastal cemeteries do not, for the greater part, represent the culture of the Incas who were at the height of their ascendancy at the time of the Spanish Conquest and which is therefore the only Peruvian civilization known to the layman. Their culture, however, like that of the Aztecs in Mexico, was relatively new and had been preceded by other civilizations of equal grade but less known. In Peru the oldest cultures were apparently those of the coast, which probably dated from about the beginning of the Christian era. Their artefacts, excavated from the desert sands, fill our museums, but of their history we know little or nothing.

The culture of Nazca in southern Peru near Pisco was one of the earliest and highest of the Peruvian civilizations, the beautiful pottery and textiles being renowned. Most of the Peruvian spear-throwers known come from the Nazca-Pisco region.

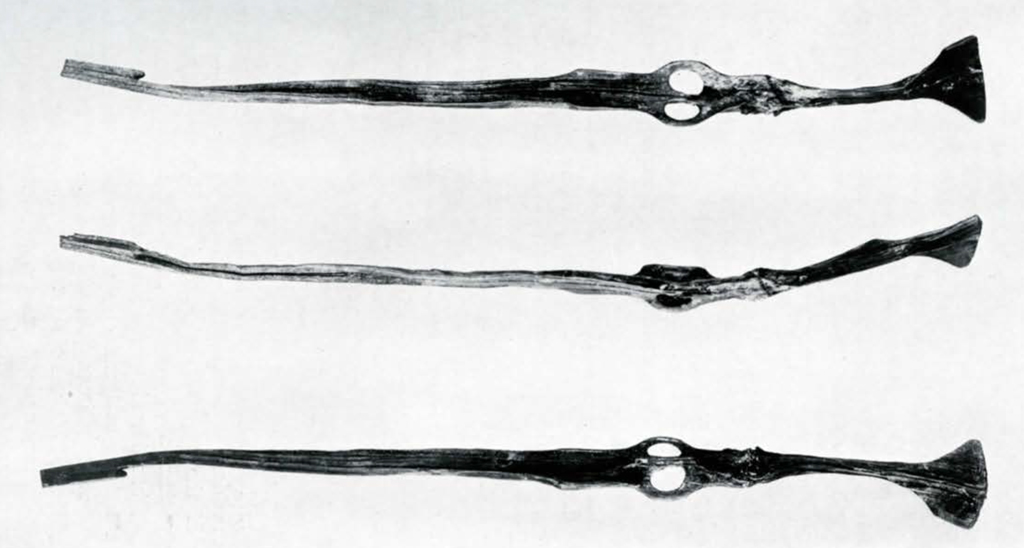

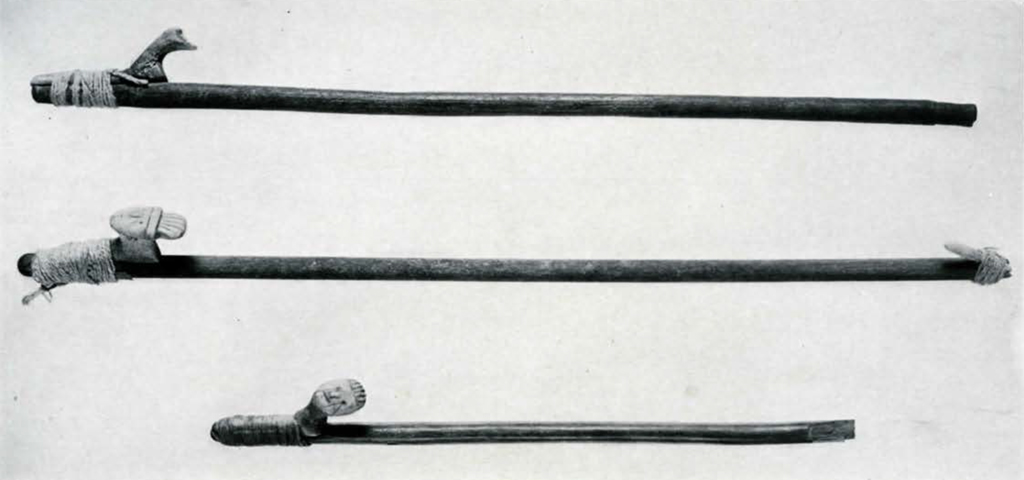

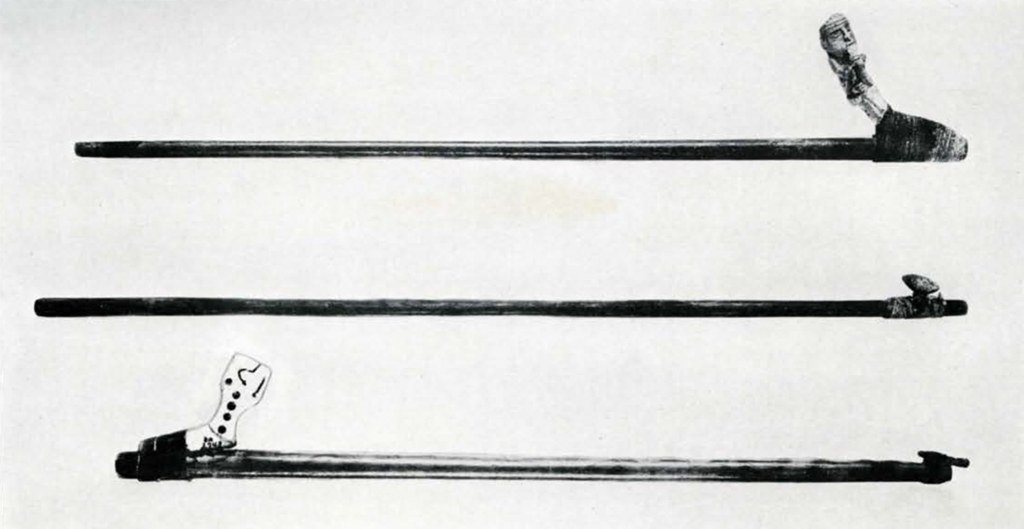

The UNIVERSITY MUSEUM possesses ten spearthrowers, whole or fragmentary, from the Nazca district. These were secured by Dr. W. C. Farabee, late Curator of the American Section, on his expedition to Peru in 1922 and 1923. Unfortunately, owing to his severe illness which later proved fatal, the data on his collections are not full, and it is uncertain whether he excavated these specimens himself or purchased them, nor do we know exactly where they were found, nor what their associations were with other objects in the same grave. Some of them, at least, seem to be from Manrique, a small place in Pisco Valley, and it is quite probable that all of them were found in the same grave. The interment of large numbers of such objects in. one grave seems to have been customary; in one recorded instance eighteen spearthrowers were found with one interment.12

These spearthrowers are all of one definite type, although differing greatly in details, but this type bears practically no resemblance to those which we have already discussed. All of the types considered before, with the exception of a few specialized forms in Alaska, have been equipped with fingerholes, either attached to the weapon or forming a part of it. The propelling spur is generally also a part of the implement or inseparably attached to it.

The Peruvian spearthrower, as may be seen on pages 315 and 317, consists of a straight, rather short stick of circular cross-section, to which a handle is attached at one end and a peg at the other. Although the main shaft is generally grooved at the distal point for the reception of the peg, yet tight wrapping with cotton cord is the main reliance for the attachment both of the peg and the handle. This method would appear much less efficient than the others, but apparently it stood the strain well.

The shafts measure from 46 to 56 cm., or 18 to 22 inches, in length, and are made of hard reddish or black woods, probably species of palm. One of them is decorated with fine incised lines which cross spirally at right angles to each other. Only three of them still retain the pegs for the spear, but these illustrate very different types. One of these, S. A. 3746, figured on page 317, is the most divergent in many respects and may represent a slightly variant phase of culture, since it is the longest, the only one made of black wood, and the only one with a copper peg. This peg is very tightly attached by means of cordage wound in a close spiral which was originally covered with pitch or tar. It possesses no handle knob, unfortunately.

The spur of another is made of hard wood, tightly bound on with cord and covered with a hard cement, while that of a third is a long peg of bone, very carelessly bound with cord; possibly the binding is modern.

The attached handle-grips and one handle which is not attached are identical in type but differ greatly in style and method of decoration. All are of bone and consist of a carved figure or hook which extends forward from the shaft at an angle of approximately forty-five degrees, and a shaft of from an inch and three-quarters to two inches and three-quarters in length. It is by this shaft that the handle is bound tightly to the main wooden shaft of the implement, the lower side being made slightly concave for this purpose. The ends of the two shafts are normally flush. The planes of the handle and of the distal peg differ by a few degrees so that the spear, when in position, lies on the left side of the handle grip where it was evidently grasped by the fingers. In three of the specimens the binding may be modern; the other two are carefully bound with cord, fixed, in one case by the use of pitch or tar, in the other of sinew.

The grip of one of the implements, S. A. 4307, shown on page 315, is little more than a hook, though it might be interpreted as a conventionalized bird. In two other instances, S. A. 4306 and S. A. 3744, shown on the same page, a human face is carved on the upper knob. This carving is in both cases quite amateurish, but displays facial decoration, either painting or tattooing. The other three are excellent specimens of carving. The unattached handle-grip, S. A. 3796, which may be seen on page 322, represents an owl or some similar bird, with wings partly opened as if in the act of taking flight. The large round eyes, prominent beak and feathered shins are well portrayed, but the depiction of the wing feathers is somewhat conventional, a small incised circle being shown on the inner part of each.

The handle-grip of S. A. 4401, the finest of the specimens, is carved in the form of a seated musician, playing upon pan-pipes. The execution is strong but rather angular and unfinished. The same could probably be said of the execution of the musician, since his pipe consists of only four reeds. The headband, binding back the long hair, the great ear-ornaments, and all other details of the figure are typically Peruvian in style. This is illustrated on page 320.

The last specimen, S. A. 3743, shown on page 317, is unique in several respects’ and may belong to a slightly variant phase of the culture. The shaft is the thickest of any, measuring eleven-sixteenths of an inch, while the others are all under half an inch, and is of a reddish wood, highly polished. The long wooden peg is fastened with a kind of cement. The handle-grip is unusual in being extremely conventionalized, probably representing the head of some animal. The eyes are deeply incised with a drill and were probably originally inlaid with coloured stones such as are employed in the four depressions in a line on either side of the neck. Here are utilized bits of violet and dark green substances, most probably shell and malachite. The nose and mouth are portrayed by means of two long thin slots which entirely traverse the bone. That for the mouth is straight, that for the nose meandering. Both were made by the technical process of first drilling a small hole, from which perforation the slot was continued by a sawing technique, probably by means of a cord or thong working in sand.

Thus spearthrowers are, as we have seen, used today by certain groups of American Indians isolated from each other and scattered from the Arctic to Brazil. Archaeological evidence and historical reports show that in earlier days their use was much more widespread. Since, doubtless, most types of spearthrowers were made entirely of wood and with the lapse of ages have disappeared without leaving a trace, the hypothesis is not ill founded that the few isolated cases of the use of the spearthrower as above described represent but the last survivals of the employment of an implement which was in the earliest days in universal use throughout aboriginal America.

1 Therkel Mathiassen, Archeology of the Central Eskimos. Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921-1924. The Danish Expedition to Arctic North America in charge of Knud Rasmussen, Ph.D., Vol. IV. Copenhagen, 1927.↪

2 Otis T. Mason, Throwing-slicks in the National Museum. Report of the United Slates National Museum for 1884, pa. 279-290 Washington, 1885.↪

3 September 15, 1893, Five years later he wrote another letter to the Internationales Archir filr Ethnographie, XI, 1898, p. 129. In the latter are published drawings of the two Basket Maker implements and of one of the Florida specimens, all three now in the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM.↪

4 George H. Pepper, The Throwing-stick of a Prehistoric People of the Southwest. Proceedings of the International Congress of Americanists, 13th Session, New York, 1902, pp. 107-130. New York, 1903.↪

5 G. H. Pepper writes, “I would correct what is probably a typographical error and state that the Mafias Canon should be Mancos Cation, which is situated in the southwestern part of Colorado.” He then states his belief that the specimen was actually found in the Grand Gulch region of Utah, and that no Basket Maker material has been found in the Cliff Dweller region of Colorado.↪

6 Bulletin 4, Free Museum of Science and Art, University of Pennsylvania, June, 1898, p. 183. ↪

7 Reproduced on pages 180 and 182 of the above.↪

8 G. H. Pepper, loc. cit., p. 112. Discoveries of the past twenty-six years may have invalidated this statement.↪

9 Frank Hamilton Cushing, A Preliminary Report on the Ancient Key-Dweller Remains on the Gulf Coast of Florida. The Pepper-Hearst Expedition. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. XXXV, No. 153. Communicated November 6, 1896.↪

10 In the text description on page 43, Cushing gives the length on eighteen inches; in the description of plate XXXII on page 95, it is given as sixteen inches.↪

11 The illustration is taken from plate XXI of Dr. Starr’s Indians of Southern Mexico, Chicago, 1899. Descriptions of the Tarascans and their spearthrower may be found in Dr. Starr’s In Indian Mexico, Chicago, 1908, and Notes upon the Ethnography of Southern Mexico, in Proceedings of the Davenport Academy of Natural Sciences, Vols. VIII and IX, Davenport, Iowa, 1900 and 1902.↪

12 Max Uhle, Peruvian Throwing-slicks. American Anthropologist, new series, XI, 1909, pp. 624-627.↪