THE wonderful discoveries made in the royal tombs have been a revelation to many and have proved that old Sumer could lay claim to wealth and beauty. The art of the day of King Mes-kalam-dug and Queen Shub-ad was a classical art, sure of its past and of its methods. Who would not enjoy visiting the old masters at home among their models in the Sumerian art shop?

Museum Object Number: B16686

Terah, the father of Abraham, if the legend is true, was a dealer in idols among the Chaldees. Coming home to his shop one day after a brief absence he found that the idols had quarrelled and the biggest of them had smashed the rest to atoms. Terah was wrong to deal in so many gods. But even his descendants found it hard to forget the golden calf. The old Sumerian had inherited from his ancestors, hunters in the Elamite hills, a keen eye for nature and a love of animal life. This, with a deep feeling of reverence towards the natural forces around him, induced the artist to multiply figures and forms. The clay, stone, or metal image fresh from his hands, was not an idle creation, or a simple memorial made for the sole pleasure of the eyes. The secret of his art, as of all Oriental art, was symbolism, which is the same as art with a meaning, art aiming at the hidden spirit behind the form. This will explain his choice of subjects and his attachment to forms, even though their primitive meaning may be lost and the traditional design be preserved only as a decorative motive.

A predecessor of the Sumerian, the Elamite artist, had drawn long before wonderful figures of animals, poor sketches of the human form, and no images at all of the gods. He was a hunter and, where no animals had yet been tamed, his life depended on his happy hunting. His art was subservient to his needs. The pictures traced by a cave man on the walls of an underground chamber are a magical way of reaching the living originals by drawing the likeness of their forms.

Spirits and souls permeate Oriental art and thought, they fill its productions, they are a natural expression of its philosophy and of its religion. A dead man has no longer words on his lips, breath in his nostrils. His spirit has gone, flown into the air like a bird. Departed souls are given the form of a flying bird. The scribe adopts it as a picture sign in his writing. But the spirit may come back to his body well preserved as a mummy in his grave, his proper home, in the absence of which the wandering soul becomes a ghost, who may prey on the living to their great disadvantage. Hence the great importance of a proper burial, out of devotion, so that the dead may have rest, and to avoid the danger of possession by a dead spirit or a demon. Seven spirits roaming in the desert decided to come back to their home from which they had been driven. They found the soul of that man clean and empty and settled in it. A likeness provided by a mask or a statue is a substitute for the body, mysteriously connected with the original from which it was copied, and also a new home for the soul, an extension of its personality. Indeed, whoever puts a mask on his face acquires a new personality. The statue of the reigning king erected in the temple will be more than a memorial. It will intercede for him. A simple clay figurine will be received as a real votive offering. Did not God himself make the first man in his own likeness, a figure of red clay, before he blew into his nostrils the spirit of life?

The bazaar is a familiar feature of Oriental life. The row of shops on either side of covered streets is the perpetual delight of idlers and visitors. Each trade has its special lane, where the merchants are to be found sitting in the midst of their goods: the jewellers, the goldsmiths, silversmiths, and coppersmiths, the dealers in rugs and perfumes, the slipper makers and saddle makers, the cabinet makers, the grocers, the butchers, the roasters. Round the corner or close to the gate are the pastry shops and the coffee houses, never far from a clear fountain, the halting place of thirsty caravans, the great market of news and gossip.

Terah’s idol shop was perhaps located at No. 3 Gay Street outside of the temple enclosure or he may have rented a small room inside, along the lane leading to the Court of Justice, between shell engravers and bead makers. Filigree jewels and necklaces of lapis, shell, carnelian, agate, crystal, of gold and silver beads sold well. The temple officials owned the more important gold, silver, and copper shops. Three furnaces for casting metal were built at the back of the registrar’s office. Here the standard weights were kept and other weights were tested before receiving the temple’s mark. Trade activity, import and export, extended far by land and sea. The clay documents in the archives have preserved a lively picture of merchants bringing in treasures from India, Persia, Lebanon, and Arabia. We will follow the devout pilgrims of the Moon God, strolling along the brick paved lanes and wondering at the works of art there displayed.

The Animal Figures

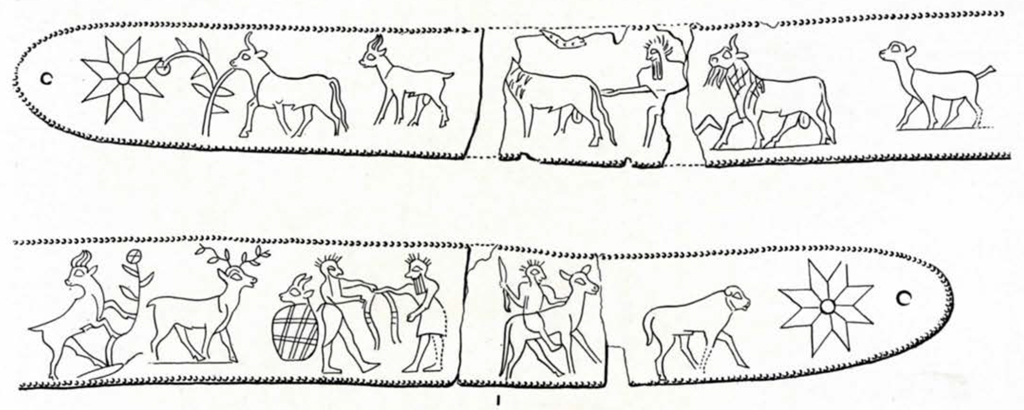

The gold diadem.—Nothing surpasses the naive charm of this frieze of animal figures worked in intaglio on a thin band of gold. It was once a diadem and was found still adhering to a broken skull. The selection of the subjects is curious, if this was indeed an ornament of a Sumerian lady. But gold always draws such a splendid line across the forehead and amid wavy locks. We are concerned only with the animal figures which seem to be borrowed from the sketch book of a hunter: five on the right, five on the left, facing towards the eight-pointed star at both ends of the band. Among them are some human figures. From left to right we see a bull cropping the green leaves on a corn stalk, a goat, a hairy, bearded bison, a kneeling man, a second bison, a kid; then a goat or antelope rampant, a stag, a crouching goat properly bagged in a net, two bearded hunters holding a rope or a pair of horns, a rider mounted on a donkey, and a mastiff which is clearly the ancestor of the Kurdish sheep-dog. The figures are simply outlined and were probably embossed by pressing the thin metal against separate engraved steatite matrices like printing blocks.

“It is clear that the figures are arranged at haphazard and do not illustrate any consistent theme. The irregularity of their base line and the varying size of the figures support the suggestion that

they are taken from stock mould. The actual workmanship is careless and superficial, some of the lines being too faintly impressed. There is a curious difference in the drawings of the animals, which are quite realistic, and that of the human beings, who are little more than caricatures. Something of the same sort is seen in the milking scene frieze from the first dynasty temple at Al ‘Ubaid.”

That faint flavour of archaism, the contrast of human and animal figures, the choice of the animals, all point towards a very ancient tradition. The bearded bison is found only on Elamite seal impressions. The Elamite hills are his real home. He is the ancestor of the mythological hero, the bull-man Enkidu. The goat rampant amid bushes belongs to the same ancient heraldry of Elam, and so also does the red deer. The Mesopotamian lowland knew only the fallow deer with palmated tines. The rider on a donkey is an interesting figure, riding astride being practically unknown among inhabitants of the plain. The fashion was probably first imported from the eastern mountains. We should like to know the nature of the object—whip or spear?—which he holds in his right hand. The two hunters with square-cut beard, wild locks of hair, and short loin cloth hail from the same regions. The doubtful object—lasso or pair of horns?—for which they seem to be struggling must have some connection with hunting and the bagged goat behind them. May the gold diadem have been an ancient heirloom or a strange work of art by some Elamite artist, brought as a present to a noble Sumerian lady?

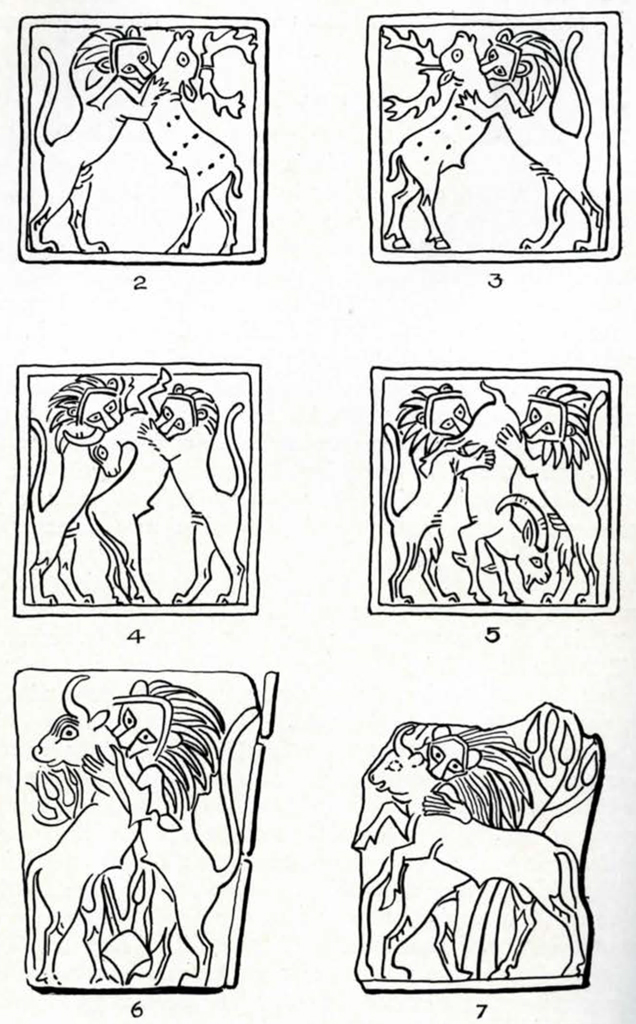

The lion.—The lion is a royal hunter. This is a favourite motive among scenes of animal life, and the beast is represented in strikingly natural poses, with real power and in daring attitudes. His head is shown either turned backward or en face, his tail is up, his mane is all bristling with locks in alternate curves like fish scales, defined by a vigorous use of the point. These animal forms are heavy but original and powerful, their combats are rude and full of energy. The rule of symmetry aims at a well-balanced composition of confronted animals. A relief border frames each subject.

Four engraved plaques show the classical grouping of a lion capturing a fallow deer or holding a bull in his terrible embrace, his fangs tearing their necks to drain out the life with the blood from their severed jugular veins. The two other plaques show still more invention and daring in the drawing of inverted bodies. A bull is attacked by two lions. His head thrown back, his front legs beating the air in vain, his hind legs thrown off the point of balance between the two on-rushing beasts, the whole affords an impressive vision of the attack. A goat occupies the same desperate position between its two enemies, but the well observed character of the leaping species has led the artist to figure it upside down, the lions avoiding the horns by grasping the hind quarters in their jaws. A picturesque landscape of high-growing plants of conventional form is the normal background of the rampant bull attacked by the lion. The subjects were selected as an appropriate decoration of the royal harps and backgammon boards. And doubtless the recital of big game hunts and the heroic deeds of famous Nimrod were sung to the accompaniment of the harp during hours of leisure.

Such scenes belong to the heraldic art of the engravers of coats of arms. They are not legendary but they are no longer the direct vision of real hunting scenes. They are the classical effort of a skilled master whose cartoons will be copied for generations. In Elam the lion is still royal game attacked with spears and arrows and a pack of dogs. He is crouching or seated or walking or charging with his tail extended horizontally. He rises on the back of his victim or faces it, crouching oddly in front, his terrible paw extended, all claws showing, ready to strike. To the realistic hunt, the Sumerian artist prefers a heroic, stereotyped, classical form of hand to hand fight. The primitive hunter is surrounded by legends and transformed into the hero Gilgamesh or his companion the bull-man Enkidu.

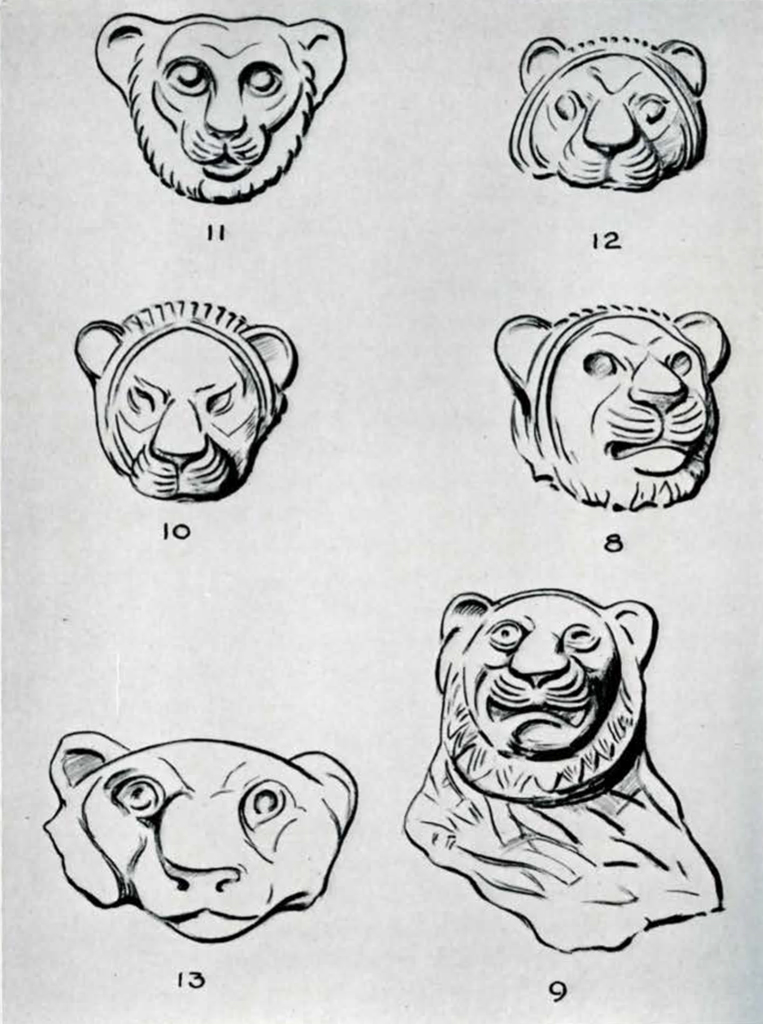

Complete heads of the lion in the round, worked in gold as a decorative motive on the queen’s chariot, fix forever the vision of the Sumerian artist and a type full of character which continued to be reproduced to the end of the Assyrian and Babylonian empires. The Sumerian lion grins; his eyes are opened widely. His muzzle is characteristically round, retracted, with engraved lines spreading in the form of a palmette. His tongue projects, his teeth are bared, the eyes are inlaid. His ruff is prominent, his mane divided into large ribbed or imbricated masses. The inlaying of eyes is a process as old as the origin of Sumerian art. The sockets were hollowed out and different materials were used, adding to the strangely living appearance of the figure. The Al ‘Ubaid lions have eyes made of red jasper for the iris, shell for the white, and blue schist for the lids. The teeth are of shell and the tongue of red jasper. All separate pieces were fastened with copper wire to the core. The wooden core was covered with metal and filled with bitumen, straw, and clay. The result is impressive, the polychromy adding unexpected effects.

Projecting lions’ heads in the round were associated with a flat or low relief of the body. The mane and the ruff might be made of inlaid pieces of shell or lapis. A tenon projected at the back of the head and was fixed to the body by a lateral peg. The full relief contrasted with the half-round produces curious and beautiful pieces.

The panther.-Two silver heads of panthers decorated the back rail of the queen’s chariot or sledge. The panther is represented but seldom in comparison with the lion and that only on very archaic works of art. The panther has not the whiskers, ruff, and mane of the lion. The skull has the shape of a cat’s head and the same erect ears. The character of the massive, powerful, and cruel beast has been well observed by the artist.

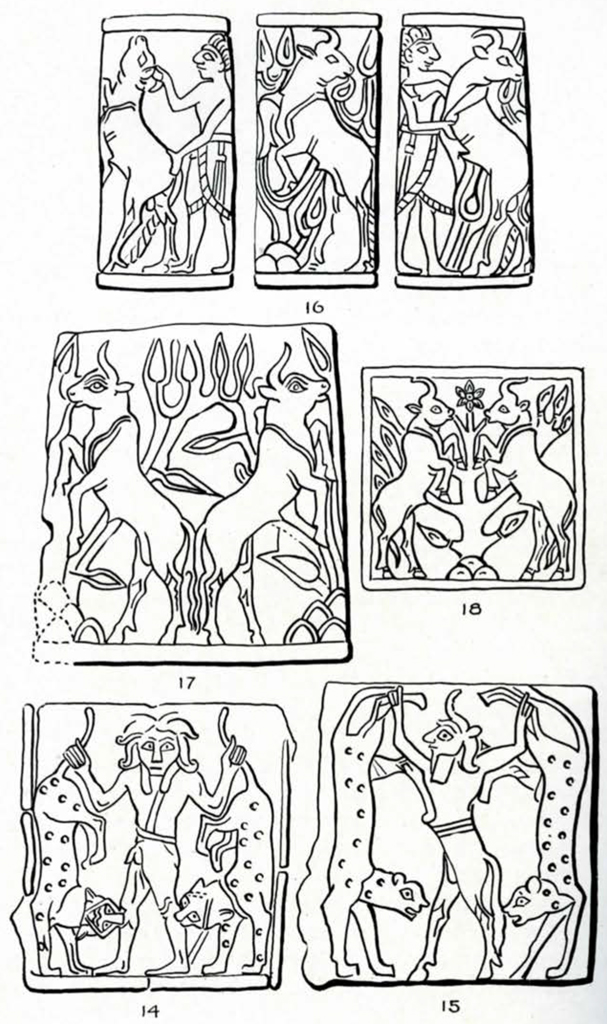

The heroic hunters Gilgamesh and Enkidu.—There is a strange story of a strange being, Enkidu, half bull, half man, whom Gilgamesh, the king of Erech, finds in the wilderness living with the beasts of the field and attracts and transforms till he becomes his inseparable companion. This is a hunter’s story of the Elamite hills, where both heroes are on their quest for adventures in the cedar forests which are the home of Humbaba, the god with the terrible voice. Art and history give to and borrow freely from legend. To the realistic Elamite pictures of the chase of the lion, the boar, and the wild goat, there succeeds in Sumer a classical art which prefers well balanced compositions, where human and animal bodies are rampant, crossed, reversed, in symmetrical heraldic groups. The teaching of a school supplants direct vision. In the Sumerian school the old Elamite art loses its rudeness and some of its originality.

But the first Gilgamesh has still much in common with the primitive hunter. He is nude or has a belt girded about his loins. His head in profile, surmounted by wild locks, becomes by degrees a classical full-face framed in three rows of curls and a carefully spread beard. He is no longer hunting with bow and arrows, spear and hatchet, in company with his dogs. He triumphs in a fight hand to hand or uses the weapons of the inhabitant of the plain: dagger, dart, club, and spear.

A classical composition opposes animals and heroes in a perfect symmetrical arrangement, or doubles them. Two lions or two panthers are lifted by the tail or by one hind leg. Their angry heads are raised in an identical posture.

The figure of Enkidu is a last stage in the transformations of art and legend. The human-headed bull, who so closely resembles Gilgamesh, is probably a hairy, bearded bison seen en face. He belongs to the Elamite series of fantastic animals with human attitudes, like the dancing bear, the donkey-harpist, and the butcher-dog. But the bull-man is a strange creation of the Elamite hunters. Not only did they represent a real bull, seated and throwing the arrows of a thunder god, but in a country where they had never figured a god under human aspect, Enkidu becomes a man without ceasing to be a bison with crescent horns and bull’s ears, rump, tail, and hind legs adorned with tufts of hair. Floating tresses hang from his neck and shoulders, his chest and arms are those of a man, and so is his beard. He is no longer wild but tamed, and a friend of Gilgamesh. Is this a last echo of the wild bull’s first domestication? His horns have been preserved as a symbol of glory and divinity on the heads of gods and god-like kings.

Engraved shell plaques representing Gilgamesh and Enkidu mastering two panthers or leopards adorned the sounding-boxes of royal harps, fitting illustrations of heroic songs in the halls of Sumerian palaces, in the land of Nimrod, the mighty hunter.

A friendly contest between a human hunter and a rampant bull may be intended as a display of strength and skill. We are still in the Elamite hills as suggested by three piled boulders and conventional bushes with ribbed stems, lanceolate buds, and star flowers. The hunter wears a fringed or embroidered kilt closing in front and a belt. He is clean-shaven, but the wild locks of his hair are tucked back and probably tied with a fillet. He is certainly different from the closely shorn, stumpy Sumerian, with his peculiar kilt closing behind and the long laps of the woollen material reaching down to between knee and ankle. The hunter has no weapon. He has locked his arms round the neck of the rampant bull or caught him by horn and tail, in both cases proving his wonderful strength. The rampant bull with head turned back, in a well observed posture, has become a classical figure of Sumerian art, and must have been fixed early by primitive artists back in the hills.

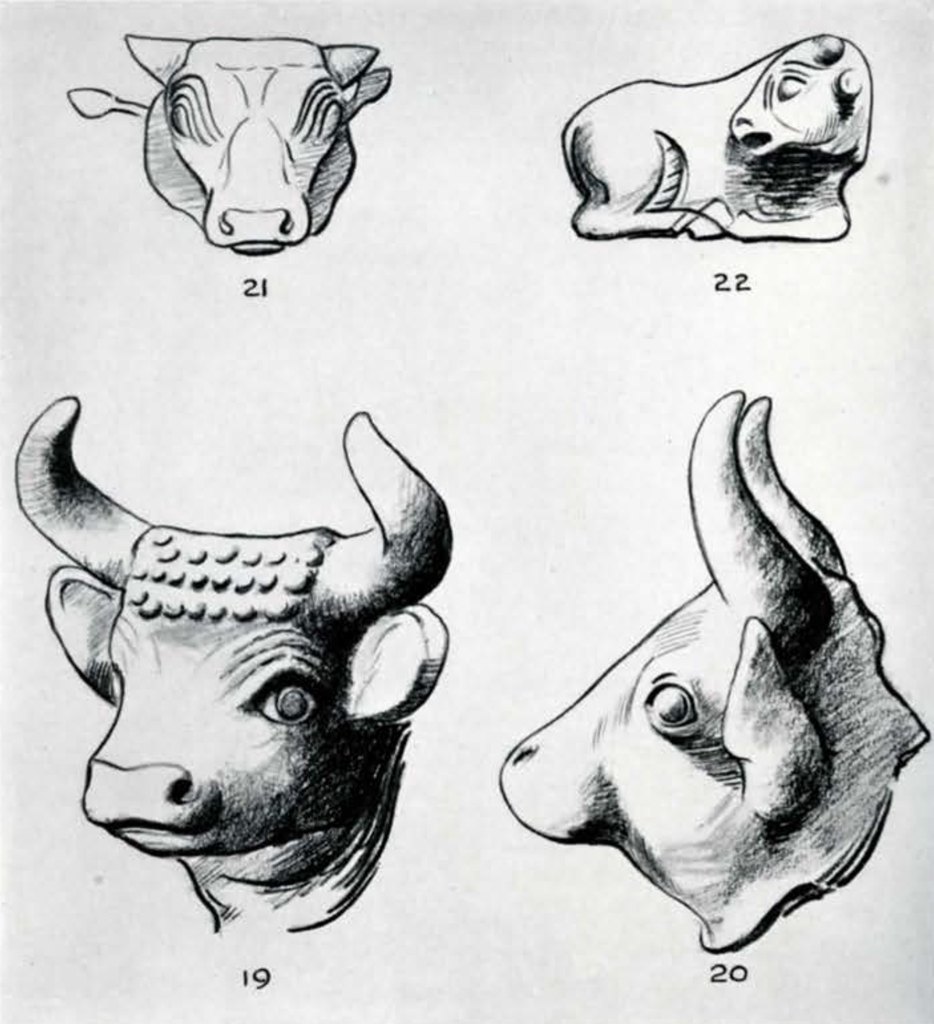

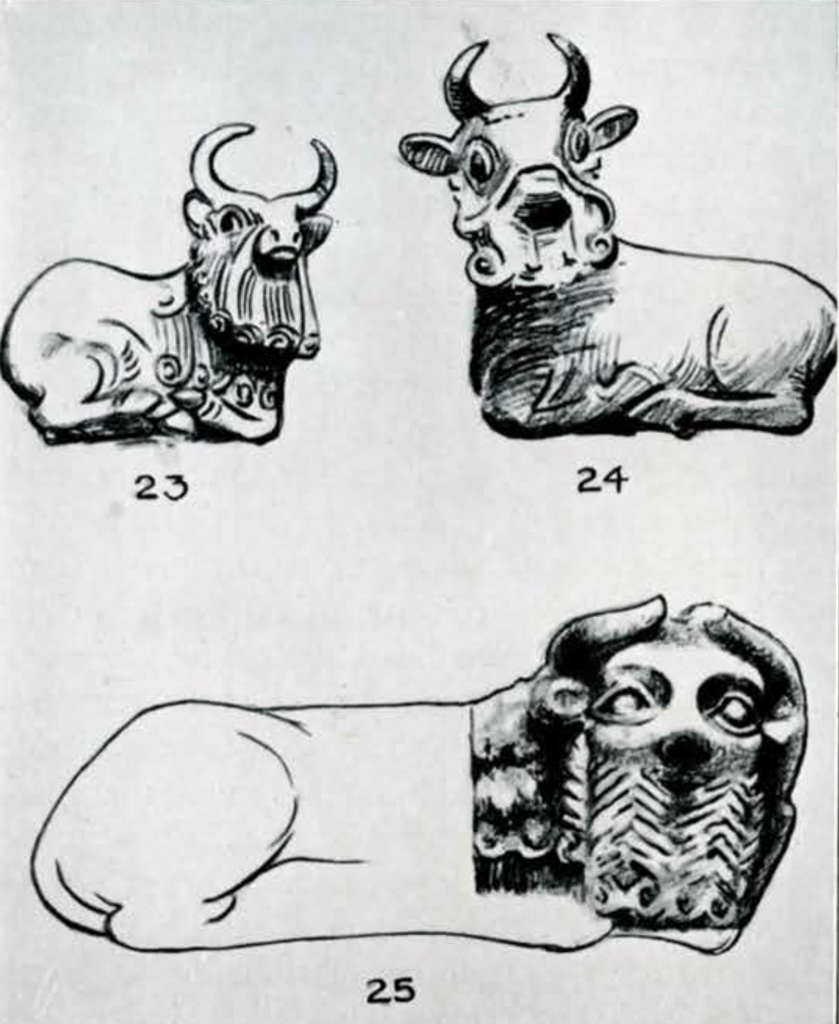

Bulls.—The same subject of rampant bulls grazing among the bushes of the Elamite hills has been used profusely by the engravers of shell plaques to decorate the royal harp and backgammon board. Animal life was a favourite motive with primitive herders and hunters were never tired of hearing of the same heroic deeds. The Moon God was called the young bull of heaven. The crescent moon was his golden horn shining over the horizon. The horned mitre had become the proper emblem of the gods. Gold, silver, or copper heads of bulls decorated harps, chariots, or thrones. A gold mascot in the form of a walking bull surmounted the rein-ring of silver. Complete copper statues of bulls in the round and friezes of crouching bulls in low relief adorned the entrance and walls of the temple of Al ‘Ubaid. In pasture land the bull was a natural image of wealth and of rejoicing in the multitude of cattle; and from immemorial time it had been the picture of irresistible strength. The golden calf was assured of a long worship.

The Sumerian bull is not a legendary figure but one of the best examples of the ancient portraiture of animals. The silver head from the queen’s tomb can compare with the best productions of Greek art, with the rhyton of the silver bull of Mycenae, with the rhyton of the steatite bull from the “two axes tomb” at Knossos. The silver head perhaps was part of a statue with engraved plaques on the chest or simply an ornament on a harp. The eyes are inlaid in shell and lapis. The round horns, flapping ears, and sleek, glossy muzzle are a true copy of nature. A second bull’s head of copper with inlaid eyes is a fine piece of work in more conventional style, with formal curls of hair and heavy superciliary folds. The technique of the bull’s head of gold and lapis, recovered with the royal harp, has turned out a curious and refined work of art. Smaller bull’s heads of gold decorated the queen’s chariot. They are cast in the round, with two projecting pieces to fix them to the back board. The head is rather that of a young bullock. The sharp points of the new horns are still in a line with the forehead, but they give character to the strong triangular head and well modelled skull. The heavy folds above the eyes belong to the same style. It is found again in the reclining calf, a lapis lazuli amulet from the queen’s grave. The pose is very natural, the head turned back, with the folds of the neck finely indicated, the mouth open in bellowing, the nascent horns, the wide eyes with their folds of flesh, the tail tucked in below the hind leg, form a vivid picture of the young animal. This amulet hung on a string of big beads of lapis and agate on the shoulders of the queen, with others in the form of fishes and antelopes.

The bearded bison of Elam has become in Sumer a legendary animal. In one case his beard seems to be attached by a string which passes over the nose, like the false beard of Sumerian kings and gods. Finally he is given the human eyes and nose, the elaborate beard and locks of Gilgamesh, and becomes the man-headed bison.

The first gold amulet from the queen’s grave represents a bearded bison, a real animal, like the stag, the ram, and the antelope, which form part of the same decoration. This was part of a royal headdress consisting of a fillet, apparently of thin leather, to which were stitched minute beads of gold and lapis covering the whole surface. Against that background were small rosettes, palmettes of thin twisted wire, branches of shrubs in gold, with gold and carnelian pods or fruits, branches of pomegranates (three fruits and three leaves) most naturalistically rendered, ears of corn, and four pairs of seated animals in gold. The bearded bison is one of them.

The other gold amulet is similar to the first, except for the string passing over the nose, which Mr. Woolley explains as follows: “The bull is represented as seated with its head turned to the front in the regular Sumerian convention. Tied under the animal’s chin by a string which passes over its nose is an elaborately curled false beard. The subject is new and admits of only one interpretation. The bull is of course a regular symbol for the god, supports his throne, and is the victim preferred for his sacrifices. The beard is essentially the attribute of divinity. The animal destined for sacrifice can, by the addition of a beard, be transformed into the very god himself, the great bull of Heaven, who gives his flesh to his worshippers to eat in true communion. Such a rite actually performed in the temple with the living beast must be represented by the amulet. The workmanship of this tiny figure is admirable. The body of the bull is somewhat summarily rendered but upon the head no pains have been spared.”

Is it not simpler to place this bull in the same category as Enkidu and the man-headed bison, than to hang the whole communion service on that beard and string? Many animals besides the bull were offered in sacrifice to the gods. The horns and not the beard are essentially an attribute of divinity.

The crouching bull which decorates an alabaster lamp has not only the elaborate locks and beard of Gilgamesh, but a human face, eyes, forehead, and nose, combined with the body, horns, and ears of the bull. Another step will further transform the strange being and by the addition of a human chest and arms will create the classical bull-man Enkidu. The three figures were familiar for centuries to the Sumerian seal cutters and engravers, but as heroes, minor characters, servants of the great gods, never to be compared with them. The bearded bison of Elam very soon took on a legendary character in Sumer, where it was unknown, and the tame cattle descending from the wild bull, bos primigenius, had no beard.

A very archaic design shows a lion-headed eagle on the back of a bearded bull with a human face, which the former attacks with beak and claws, one of the strangest motives of the old Sumerian picture gallery. The traditional group is seen, rather poorly engraved, on one of the shell plaques found in the disorder of the filling of the dagger grave. It must have been part of the decoration of a gaming board. The same group is known from a beautiful limestone relief from Al ‘Ubaid, placed this time in a real Elamite landscape of hills and shrubs. The bird is turned the other way, grasping in its beak the hind quarters, not the shoulders, of the bull.

The lion-headed eagle.—The legendary figure has become heraldic. The well balanced composition is a perfect coat of arms. It was studied in the last MUSEUM JOURNAL and is reproduced here on a larger scale to afford a better view of its style and technique. The imperial bird has seized in its claws two leaping goats or ibexes. The side view of the claws is in the Elamite tradition. The ibexes are evidently mountain game. The lion’s head en face belongs to the same Sumerian art as the Gilgamesh head in front view. Mythology combined lion and eagle in the same spirit which created flying dragons or man-headed bulls, legend transforming and combining naturalistic figures. The checkered feathers on body and wings represent an original made of inlaid pieces of coloured stones and shell. That legendary development of art is properly Sumerian.

The spread-eagle and the serpents.—A fragment of a pre-Sargonic vase in soapstone from Nippur, now in Constantinople, shows a real eagle one step nearer to the Elamite tradition. The bird’s head is drawn in profile with a round eye and a strong curved beak, from which protrudes the point of the tongue. The serpent’s head is drawn in the same realistic style, jaws opened, hissing, ready to bite. The claws of the bird are represented sidewise as in the previous coat of arms. The tail is spread wide, and the body is too short for the strong legs. But the whole design has strength and character. The holes cut in the surface of the low relief were probably inlaid with mother of pearl.

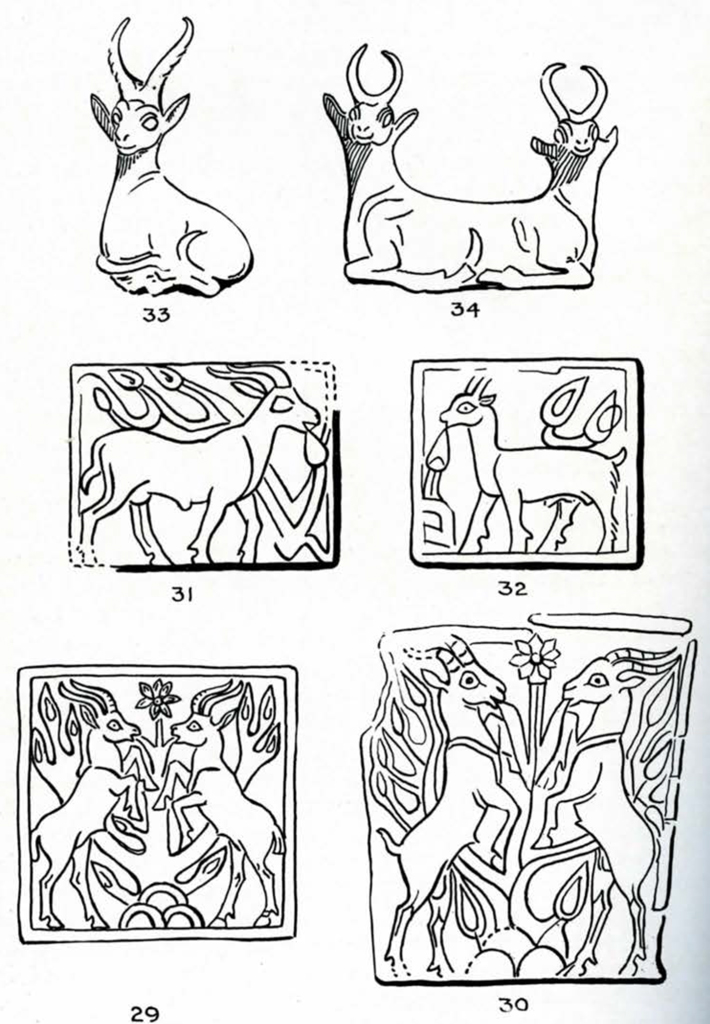

Wild goats and antelopes.—These graceful species of horned animals are difficult to distinguish in the Sumerian drawings. It is easy enough to distinguish bulls and deer and to recognize goats when the artist was careful to trace their pointed beards. But in the absence of the beard, gazelles, antelopes, wild sheep, or ibexes may be intended, when there is no certainty of distinction between straight, curved, simple, double, or spiral horns, en face or in profile, smooth or rugose. Larger size may denote antelopes, but most of the rugose horns must belong to ibexes or wild mountain goats. On engraved plaques, the two horns are drawn separately.

The classical grouping of two rampant animals in a conventional landscape of shrubs and mountains is the same as that of two rampant bulls. It was drawn by the same artist to decorate the same harps and gaming boards. Other designs of much poorer workmanship represent the same ibexes clumsily moving among odd-looking shrubs. Gold amulets in the round made for the queen are little masterpieces of much finer art. The position of the couchant animal on the alert with head erect is well observed. And the grouping of two animals of the herd keeping close together for security is very natural and forms a happy motive.

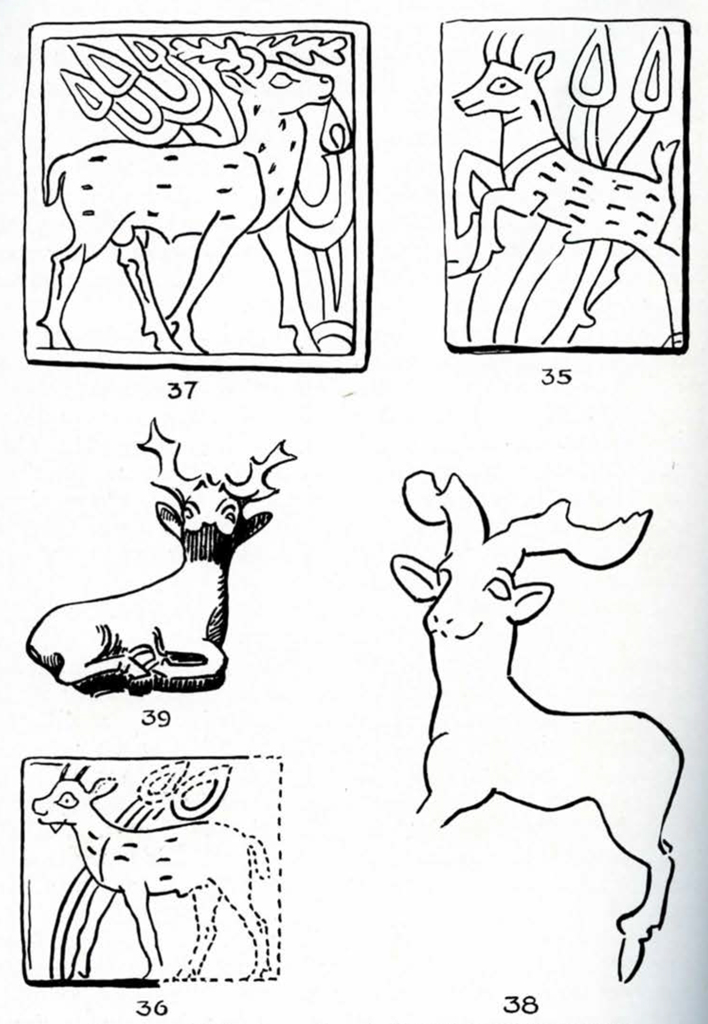

Deer.—The Sumerian artist seems to know, or to draw, only the spotted or fallow deer with palmate antlers and less developed tines. Whether the red deer or maral of the Caspian provinces with the long bare antlers and numerous tines was known as real or only as legendary game is hard to say. The red deer is represented in the large copper relief of Al ‘Ubaid, his antlers and tines hammered separately and soldered with lead in their socket. On engraved shell plaques the spots of the fallow deer are obvious. The graceful animal is moving or leaping through a thicket of leaves. No one with a sense for line and proportions can help admiring the strong, sure outline of the best examples and the lifelike movements of the body.

Two examples in the round, one in gold, a crouching figure from the queen’s dress, and one in copper found at Kish, show the same mastery of characteristic form and life.

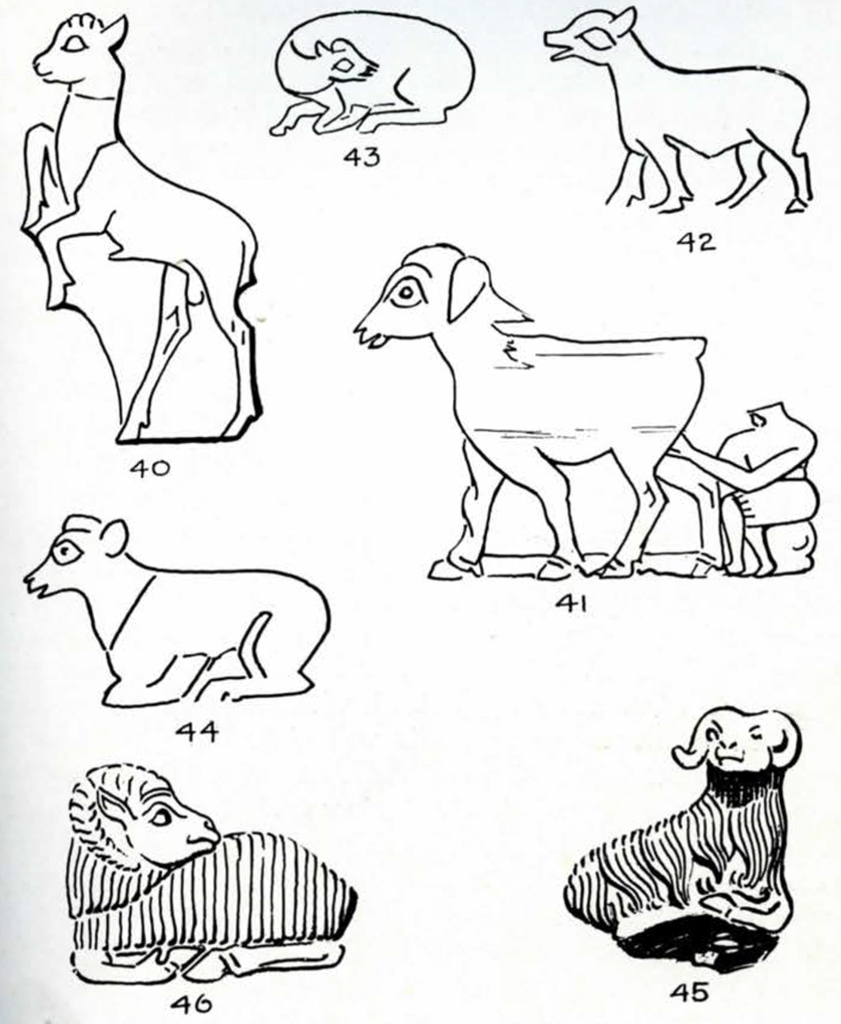

Tame animals.—A small selection of tame animals cut in pieces of shell for inlay and simply outlined in very low relief and also some gold and lapis amulets in the round prove the exquisite and truthful sense of observation of the Sumerian artist. The lively and graceful attitude of the springing kid was caught from nature. The ewes, lambs, and rams are reclining with heads raised or turned, they are moving by or waiting to be milked. The examples were found in Ur, Kish, and Lagash, where the same models were copied by the same generation of artists. The long locks of the ram’s fleece are treated in a conventional style and comparison with the Sumerian petticoat suggests that the latter was primitively a fleece complete with the tail showing as a heavy knot behind.

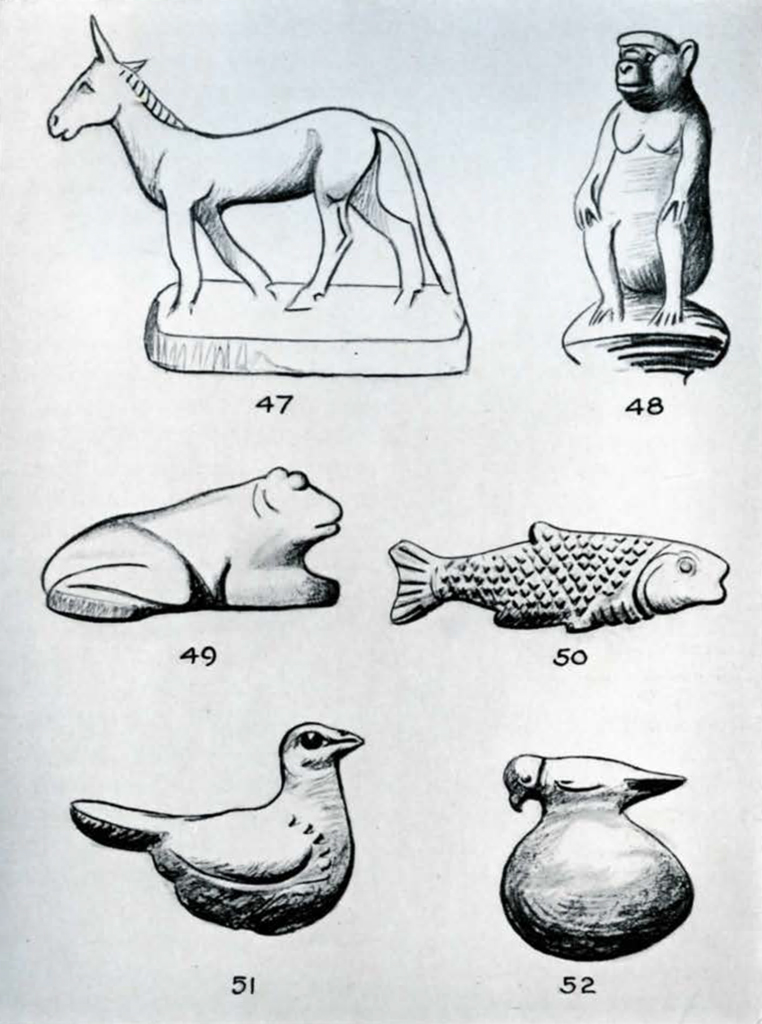

The ass.—This most realistic piece of modelling is well known to JOURNAL readers. It is an electrum mascot surmounting the silver rein-ring of the queen’s chariot. The identity of the species has been questioned. Does it represent a horse or a mule? This of course would suppose the horse to have been known at that early age in Mesopotamia. The hind quarters seem too round and powerful for a donkey. The appearance of the horse in Babylonia has hitherto been placed about 2000 B.C. It was imported from Mongolia across the highlands of Persia at the time of the invasions of Hyksos and Cassites, and was called the mountain ass. The charioteers on the inlay stela use teams of animals of the same type. Can they really be horses? So far as we can trust the artist’s modelling, the beasts have well developed hind quarters, stronger than is normal in modern donkeys. We cannot judge of the shape of the hoofs. But the animals have also the long neck, drooping ears, and long tail which we scarcely expect to see in the Mongolian horse or Shetland pony. And why should not the royal team have the best donkeys in the land, the famous breed of Eridu? The argument derived from the notorious obstinacy of the donkey and the improbability that a team could be driven four in hand is humorous but not convincing.

The monkey.—The miniature figure of a monkey in gold was found with other amulets, a ram in lapis and a frog, and many beads forming various necklaces by the side of the body of King Meskalamdug. It is mounted on a stem and formed the top of a long pin. The attitude of the squatting animal, with hands resting on knees, with keen eyes and erect ears, is well observed. The monkeys imported from the southeast, perhaps from India, must always have excited a humorous curiosity. Monkey dealers are represented in terra cotta figurines. They carry their pet animals on the shoulder or lead them on the leash. On seal cylinders the monkey with raised hands is a symbol of adoration. Monkeyish tricks must have been early credited as evidence of real intelligence. No wonder that an artist enjoyed sketching the queer little figure.

The frog.—Many frog amulets in clay, frit, lapis, or shell have been found in the excavations at Ur. They are essentially a symbol of water, marshland, and canals, always represented squatting on the ground, ready to jump. Miniature figures were cut in mother of pearl and hung with beads on a necklace.

Fishes.—The fish is the obvious emblem of running water. It is a staple food in South Babylonia. The carplike white fish of the Euphrates may grow to very large proportions. The hero Gilgamesh is sometimes represented carrying four or six of them, a good catch. Mythology knew a strange being, a fish-man, who came out of the sea in very ancient times to teach the rude inhabitants of Eridu the first elements of civilization. A goat-fish was the emblem of the god of Eridu, god of wisdom and of the deep abyss. But figures of priests dressed in fishskin are late and due mainly to Assyrian artists. The Sumerian artist was satisfied with little amulets in gold, lapis, or clay, representing real fishes.

Birds. —Water birds, ducks, geese, pelicans, are most common in Mesopotamia, especially in the southern marshland. Weights were cut in the form of ducks, swimming or resting on the water, with their heads turned and resting on their backs. The goddess Bau was in charge of that goose paradise. Ducks and geese surround her and form her throne and pedestal. But while the stone-carver was satisfied with ordinary water fowl, and lacked the keen eye of the Egyptian artist for animal forms, hair, and feathers, the jeweller at least could cast and chisel remarkable gold amulets representing other birds such as the dove and the sparrow. The first is a gold bird with a lapis tail. The second is a little gold bird on a fruit. The amulet measures only 10½ mm. and the bird 3½ mm. The eyes and feathers are most faithfully worked. The character of the bird is wonderfully well caught.

Lastly, a fragment of a stone vase from Nippur has a figure of a goose, with aquatic fruits and plants, incised upon it. It is a rough sketch in outline, but not without character.

With a more intimate knowledge of the works, ideals, and technique of the old Sumerian artists, our sympathy and respect is sure to grow.

List of Illustrations

- Gold diadem, U. 8173. Published in Antiquaries Journal, vol. VIII, no. 1, p. 23. MUSEUM JOURNAL, June, 1927, pp. 142, 143.

- Engraved shell plaque from a gaming board. From the royal tomb (C). MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 21.

- to 5. Idem.

- Engraved shell plaque, U. 10577. Decoration below the copper bull’s head. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, pp. 23 and 26.

- Engraved shell plaque below the golden calf’s head, on harp of Queen Shub-ad. MUSEUM JOURNAL, Sept., 1928, pp. 236 and 239.

- -12. Gold lions’ heads decorating the sides of the chariot of Queen Shub-ad. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, pp. 15 and 16.

- Silver panther’s head. Same as above.

- Gilgamesh and the two leopards. engraved shell plaque. As 6.

- Enkidu and the two leopards. Engraved shell plaque. As 7.

- Loose engraved shell plaque, U. 9907.

- Engraved shell plaque: bull and lion. As 7.

- Rampant bulls. Engraved shell plaque. As 2.

- Copper bull’s head from the royal tomb, Pg. 789. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 26.

- Silver bull’s head from Queen Shub-ad’s tomb. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 23.

- Gold bull’s head from the queen’s chariot. As 8-12.

- Reclining calf. Lapis amulet from Queen Shub-ad’s tomb, U. 10946. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 26.

- Bearded bison of gold. Ornament of Queen Shub-ad’s second headdress. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 30.

- Gold bull amulet, with a false beard tied by a string, U. 8269. Published in the Antiquaries Journal, vol. VIII, pl. IX, no. 1, and p. 22.

- Man-headed bull on a an alabaster lamp. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 31.

- Walking bull. Engraved shell plaque found in the fillling of the dagger grave. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, pp. 6, 7.

- Lion-headed eagle seizing ibexes. Engraved shell plaque. As 7.

- Fragment of a pre-Sargonic stone vase. Nippur. CBS. 4930. Cast of an original in Constantinople. Eagle and snake. Low relief on soapstone probably inlaid with mother of pearl. Flat bottom and slanting sides. 212 x 215 mm.

- Rampant ibexes. Engraved shell plaque. As 2-5.

- Rampant ibexes. Engraved shell plaque. As 6.

- , 32. Walking antelopes. Engraved shell plaque. As 26.

- Reclining antelope. Gold amulet from the tomb of Queen Shub-ad. As 23. U. 10948.

- Two reclining antelopes. Gold amulet, U. 10943. Beside the fastening on the right arm of Queen Shub-ad. MUSEUM JOURNAL, June, 1927, p. 147.

- Fallow deer leaping. Engraved shell plaque, U. 8915. The Antiquaries Journal, vol. VIII, pl. viii. MUSEUM JOURNAL, June, 1927, p. 147

- Walking fallow deer. Engraved shell plaque. As 26.

- Walking fallow deer. Engraved shell plaque, U. 9119 9or 9112?). The Antiquaries Journal, vol. VIII, pl. vi. MUSEUM JOURNAL, June, 1927, p. 148.

- Copper figure in the round. Kish, pl, XXVIII, 2, and p. 98.

- Reclining fallow deer. Gold ornament of Queen Shub-ad’s second headdress. As 23.

- Leaping kid. Shell plaque cut and engraved. From TEllo, Déc., pl. 46, p.269; Cat. no. 227.

- Milking scene. Kish, pl. XIII and XLII. Limestone pieces cut from inlay.

- Lamb. Figure from a slate plaque. Kish, pl. XIII and XLII and p. 72.

- -44. Figures from Kish, pl. XIII and XLII.

- Reclining ram. Gold ornament of Queen Shub-ad. As 23.

- Lapis ram, amulet from the tomb of King Meskalamdug, U. 10009. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 9.

- Electrum donkey, U. 10439, from the queen’s chariot. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 17.

- Monkey of gold, U. 10010. As 46.

- Frog, a lapis amulet, U. 10008. As 46.

- Fish amulet of gold. U. 10944. From Queen Shub-ad’s tomb. MUSEUM JOURNAL, March, 1928, p. 26.

- Gold bird with a lapis tail, U. 9076. Antiquaries Journal, vol. VIII, pl. IX, no. 1, and p. 22.

- Gold bird on fruit, U. 8005. As 51.

- Fragment of stone vase from Nippur. Original missing. Known from a photograph, vol. IV, no. 210. Published in Bêl-Tempel zu Nippur, Abb. 51, p. 59, as “Zeichnung eines Tempel-schülers,” which is wrong.

All the drawings have been made by Miss M. Louise Baker.