FOR the present purpose, Upper Guinea may be taken, roughly, to mean the southern part of the westward extension of the African continent between the Cameroons and Senegambia, a territory which is peopled mainly by tribes in which the negro strain is either as nearly as possible unmixed or is predominant. From this part of Africa numerous striking customs have been reported which reveal a strong interest on the part of these peoples in multiple births of children, especially, so far as the reports show, in the birth of twins.

The existence of an interest manifesting itself in special forms of behaviour towards twins in many parts of the world has strongly impressed not a few writers who have occupied themselves with the study of one phase or another of human conduct or history and attempts have been made to link up observances of the kind indicated in widely separated parts of the world in the effort to account for observed similarities, often superficial, on the ground either of highly improbable contacts or of a unilinear process of evolution exemplified in necessary stages of mental development supposed to have been passed through by all human groups in common. Diversities in the observances in question and in the mental attitudes from which they seem to have arisen even in so comparatively restricted an area as that of Upper Guinea do not lend much support to such generalizations—certainly not to the latter.

It is not easy to see how, among peoples at about the same cultural level, as the case is with many of these Guinea negroes, a contemporary custom such as that of killing twins because of their essential twinness could have evolved from that of gratefully accepting such births for the same reason, or vice versa. For these two opposed attitudes we can, it is true, discern an elementary common ground—common, it would seem, to all peoples who have left evidence of an emotional attitude towards twins—in what was, primarily, no doubt a but slightly differentiated instinctive feeling that twins are abnormal, therefore in some way portentous. But this feeling, once realized, seems to have given rise to two opposed lines of action leading each to customs necessarily diverse and existing contemporaneously among peoples of substantially the same degree of culture.

Between the extremes of abhorrence of twin births, leading in many cases to twin murder, and the grateful reception of the twins into the community, there is an attitude of toleration which may be partly or wholly due to the influence of these extremes on one another in territory which as been the field of clashes and accommodations. There is at any rate no reason to reject this as a possibility in a restricted area like that of West Africa or even with regard to Africa as a whole.

The existence of an originally largely undifferentiated feeling about the abnormality of twin births can be exemplified from instances of its survival both among tribes who bar twins and among those who welcome them. Of the former, the Jekri, a Yoruba people whose country lies south of Benin to the west of the Niger delta, hold, or held, that it is quite unnatural “to bear twins,” while of the peoples of Southern Nigeria in general it has been said that “the main grievance”-among those who object to twins-“was that they were abnormal;” and among the Kafirs of South Africa it was believed that the birth of twins was “entirely out of the ordinary course of nature.” The Baronga, near Delagoa Bay in Portuguese East Africa, for whom twins are children of heaven, have a special word yila to donte “derogations from the laws of physical nature” such as “the bringing of twins into the world.” A similar feeling, expressed without the unfavourable bias that some of these forms of expression seem to imply, is deducible from utterances on this subject of others who favour twins.1

A sort of rationalization of this feeling has occured, broadly, in two directions, one rather naturalistic, the other supernaturalistic. Thus we are told that in Southern Nigeria the abhorrence of twins is “due apparently to the conception that one birth at a time is the distinguishing feature between man and all other creation;” in other words, that twin bearing is a beastly habit. In Northern Nigeria, “their mode of birth is non-human.” IN Dahomey, if the proper ceremonies are not performed, the twins will become monkeys again. Among the Ho of Togoland, the flesh of the hussar monkey is taboo to twins and their parents, the children being known as “hussar monkey children”. Of the Kafirs referred to in the last paragraph as holding the birth of twins to be “out of the ordinary course of nature” we are also told that they explain this by saying that bearing twins is like dogs or pigs, disgraceful.2 In this view, then, it appears that, so far as twin-bearing is reprobated, it is the resemblance to the littering of animals that makes the event “unnatural” and shameful. The Dahomans and the Ho, related peoples, though they seem to have reached a similar interpretation of an unusual, if not abnormal, occurrence, do not disapprove of twins.

A transition from the more naturalistic explanation to one which appeals to supernatural considerations is seen, e. g., in the case of the monkeys which are made responsible in Dahomey and Togo and to which the twins appear to be in some kind of mystical relation. Having regard to the ideas of reincarnation which are prevalent in Guinea, Foa’s statement that twins may become monkeys again gives a clue to what this relation may be—unless, as good evolutionists, we are to regard this as an instance of atavism! Some of the peoples who explain their dislike of twins on the ground that a twin-bearing faculty is natural to animals, ergo unnatural in human beings, impute the transference of this bestial quality to the intervention of spirits. The Southern Nigerian peoples who bar twins, according to Major Leonard, ascribe the “unnatural event . . . to the influence of malign spirits,” and Foa’s twins, who may revert to apishness, have, associated with them, a genie persécuteur, to avert whose influence requires a whole series of ritual precautions.

The intervention of spirits to bring about the birth of twins, the supernaturalistic explanation of twin births, is seen to be a natural outgrowth of the almost universal feeling that such births are abnormal, therefore portentous of good or evil, although it is not claimed that it is only in the way suggested that this process may have taken place. Any apparent irregularity in a situation so surrounded with an emotional atmosphere as child-bearing is, will in communities strongly governed by superstition almost inevitably be explained by reference to spirits malicious or benevolent, or who may be either according to circumstances conceived in a society where the categories of dualism in religion are not firmly established.

Spirits intervene in a large number of reported instances to cause the birth of twins, or are otherwise intimately associated with them, both (1) where twins are held in abhorrence and therefore destroyed, and (2) where they are welcomed and surrounded with precautions to insure the continuance of the favour of the spirit or god who has blessed parents and community with so prized a gift or who has taken the twins under his special care.

1. Among the Yoruba of Southern Nigeria it is believed that twins were in former times generally destroyed. Until recently one of the pair was thought to be non-human and was allowed to perish of neglect or exposure. Special precautions were taken to prevent the malicious spirit of the dead child from tormenting the survivor. Among the same people in Northern Nigeria, as in the case of the twin-killing tribes of Northern Nigeria in general, it is said that one, at least, of the twins is an evil spirit. Of Benin, which was governed by a Yoruban dynasty, it is said in a report which dates from the early 18th century that there the mother of twins and her infants were killed as a sacrifice to a “devil” who dwelt in a wood and who, presumably, was responsible for the mischief. The Ibo of Onitsha, on the lower Niger, believed that twins are a punishment inflicted by Ani, the Earth Spirit, for a crime committed by the mother. In Kratyi, Togoland, on the Ashanti border, it was believed that an evil spirit was concerned in the birth of twins. In the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast deformed children and, sometimes, twins are considered to be “devils” and to nullify their evil influence they should be destroyed. To return eastward to Nigeria, it is said that some of the tribes of the southern province regard twins as the offspring of a demon or as due to the “influence of malign spirits” and “the power of evil” or to possession of the yielding and hence offending parent “by some intruding and malignant demon.” In Yorubaland, where there has apparently been a humane reformation in the attitude towards twins which is not entirely due, as it is among other twin-killers, to European, and therefore recent, influences, the child born next after twins has a special name which is explained by the comment “the devil after twins”; and the mother who fails to give birth to this Idowu may go mad—the “wild and stubborn Idowu” that has failed to get born “flying into her head?”3 Probably this “devil” was in possession before, or at the time when, the mother conceived twins, was the cause of this conception, and comes to birth himself only when he has fulfilled his mischievous mission or, frustrated of his proposed incarnation, punishes the unfortunate vehicle of his malice with madness.

Passing beyond Upper Guinea, as in the cases of the Baronga and the Kafir above, for purposes of comparison and by way of illustrating the wide extension of similar beliefs and practices about twins in Africa, we find that the Bakongo of the old kingdom of Kongo, south of the river of that name, are warned on the occasion of the birth of twins not to go abroad that day for wood or water lest they should meet the spirits of the waters and forests, who would thus seem to have a connection with such births. According to Weeks, it was customary to allow one of the twins to die of starvation. Father Van Wing, to whom we are indebted for the information about their spirit connections, apparently does not know of this custom. His account deals chiefly with a remote group of this people, in the northeastern part of Bakongo country.4

2. The tribes of Northern Nigeria which welcome twins say that their birth is due to the direct intervention of well-disposed spirits. In Edo (the kingdom proper of Benin) in Southern Nigeria, the coming of twins is explained as follows: Osa, the supreme god, allots to a man so many children; if one dies, it is born again. Ehi, the primary soul of an individual, leads a child into the world; it is in Elimi, the place of souls, until it comes into the world. If two ehi play with one another in Elimi, one ehi follows the other into the world and twins are born.5 In addition, then, to the intervention of a god in the production of twins, an origin which they share in this case with other children, we have here a rare account of the prenatal condition of twins. Another such, differing in detail and containing a character who bears a quaint illusory resemblance to a Rhadamanthus assigning prenatal instead of post-mortem destinies, I have lately heard from a Sobo (Uzhobo) now living in Philadelphia. The Sobo are neighbours of the Edo or Bini people. My informant is the nephew of the chief of Ovu. His name is Mosalo (anglice Moses), and I relate here his story with such reserve as is due to the fact that no other source of information is available for purposes of corroboration. Mosalo says that in his part of the Sobo country twins are believed to be a gift from the god Egyu, to whom a sacrifice is offered on the occasion of the birth of twins. There is another god, Uzholu, who assigns to each person his destiny before he comes into the world from some such limbo, presumably, as the Elimi of the Bini. Two infants conceived in one womb and begotten by one father come into the world as twins by virtue of their own decision ratified by Uzholu. This decision, having been made in answer to the question put by Uzholu to each person before he is born as to what he wishes to be or to become in the world, must be rigorously kept to after birth and the behaviour observed by and towards twins among the Sobo of Ovu is part of the unchangeable lot of those who decide before Uzholu to be born into the world as inseparable companions.

The connection of twins with monkeys which has been recorded for Togo and Dahomey obtains also in the neighbouring coastal region of Yorubaland, between Lagos and Badagry. Here there is a temple to Ibeji, which is the goal of pilgrimages made by twins and their parents. This Ibeji, whose name means “twins”, is said by Ellis to be “the tutelary deity of twins” and to correspond to a similar deity of the Ewe-speaking tribes of Togo and Dahomey—the same people who, we have seen, attribute a mystical relationship to twins and monkeys. A small black monkey is sacred to Ibeji, offerings of fruit are made to it, and its flesh is taboo to twins and their parents. Whether Ibeji is actually responsible for the bringing of twins into the world or not, is not clear, but it seems probable. We are evidently here concerned with a set of beliefs relating to twins which are common to the Ewe-speaking peoples, including the Ho of Togo, and the Yorubans, at least those of the southwestern part of Yorubaland. At Popo, on the Dahomey-Togo border, and at Porto Novo in Dahomey, near the Yoruba frontier, the gods of twins are known respectively as Ahoho and Igbeji. The latter word is evidently the Yoruba Ibeji. Ellis gives the form Hoho for the Ewe god whom Foa calls Ohovi. This on the face of it seems to be a reduplication of the name, Ho, of some groups of the Togo Ewe; and appropriately enough, on a superficial view, whether in this respect or in that of a physically formal connection with a duplex phenomenon, the Popo deity is said to be represented by a man and a woman sitting side by side.6

Of the Yoruba in general it is said that certain children who receive special names on account of peculiar circumstances attending their birth are sent from heaven. Twins are among the number. The Gouro of Bouaflé in the French colony of Ivory Coast sacrifice to a tutelar of twins, who is, however, also said to be “patron of children” in general. The Bambara of the French Sudan consider that twins are sent as a special blessing from the supreme god, the creator. The Habbé of the central Nigerian Plateau sacrifice to Amma or Ammo (Amba), their god of the sky, in gratitude for having sent them the special blessing of twins. The Baronga in South Africa, to whom reference has already been made, call twins “children of the sky” god—a circumstance of which much has been made in the attempt to connect negro customs relating to twins with “Heavenly Twins” in Greece, India, and every other part of the world from which the most remotely similar observances have been reported. It is not so far a cry to British East Africa, where, in the Mount Elgon district, the belief of the Bagesu in the intervention of the gods is evidenced in their conviction that the anger of the gods was directed against that one of the parents of twins whose sex was not represented in a pair of twins of whom both were male or both female. According to the Baganda, not far to the west, “it was from Mukasa” —chief among their gods—” that the great blessing of twins came; he was said to show his esteem for certain women in this manner.”7

A number of the most striking and characteristic examples of the negroes’ ways of explaining the production of twins naturalistically and also from the supernatural point of view having now been given, it remains to notice three less common modes of explanation. One of these, though in a measure naturalistic, rather begs the question if taken by itself and in fact appears to be given by way of supplementing that explanation which rests on the concurrence of spirits. The bearing of twins, say those tribes of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast who consider twins unlucky, is a hereditary failing. With this opinion may be compared that of the Kafirs who have the same prejudice, and who believe that through close contact with twins men may communicate the twin-bearing tendency to their wives. So they refuse to sit long with a twin or to eat with one.8

This leads to the second of these three forms of explanation. It appears to be founded on a belief in magical agencies, which often work through contagion. It is even likely that such a belief may be at the bottom of the practice of killing twins and killing or banishing the mother, “lest contact with the defiled might cause some other woman to bring forth twins.”9 Among American negroes there is a belief that eating twin apples or any other kind of twin fruit will cause a woman to bear twins, an idea which is perhaps derived from the Ibos of Upper Guinea. Leonard’s notion of defilement, uncleanness of the mother, etc., is probably in fact equivalent to the idea of the contagious nature of twinness, this curse brought on a community through the malignity of an ill-disposed spirit power. For the same reason, no doubt, some of the Ibo and some other populations in the neighbourhood of the Niger Delta are enjoined to throw away or destroy food or other property which happens to be in the house or even sometimes in the quarter of the village where twins are born. The house itself is sometimes destroyed. Property may be confiscated by the priest of Earth and, at least in one reported case, ransomed from him. A similar case of ransom of property by the parents of twins from the officiant at ceremonies connected with the birth of twins has been reported from the Ewe-speaking Ho of Togo, who welcome twins with elaborate celebrations. That twins can be produced through the voluntary exercise of magical powers by a human being is the belief of some of the inhabitants of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast, who say that a certain “medicine” placed on a stone in the field where a woman goes to work will cause her to bear twins if she sits on the stone.10

We have seen that among the Ibo of Onitsha the Earth visited the punishment of twin-bearing on a mother guilty of crime. One of the crimes specified in this connection was adultery; and we find several other instances of adultery being considered responsible for multiple births. At Benin, the late Iyashere, or senior war-chief, an important court official who customarily married the king’s sister, was presented by his wife with six children at one birth. “It was thought that their birth was due to her having possessed many lovers.” Of Benin also, O. Dapper, a seventeenth century Dutch writer, says: “Many people are surprised at not seeing any twins in this country. This is because a woman’s honour is lost when, at Benin as well as at Arder (Ardra, Alada in Dahomey), she is delivered of two children at one birth.” This is from a French translation published in 1686. The corresponding passage in an English translation made for H. Ling Roth (Great Benin, p. 35) from the Dutch original of 1668 makes no mention of Dahomey, and the concluding words are: “They firmly believe that one man cannot be the father of two children at the same time.” The Yoruba of Northern Nigeria and certain other tribes of the same region who do not welcome twins, besides accounting for their attitude towards such births by the belief that one of the twins “must be an evil spirit,” also sometimes declare that twin-bearing is the result of adultery. Presumably the fault of the mother is the opportunity of the intrusive spirit. The Jekri, Sobo, and Ibo of Warn district, south of Benin, according to one report, believe that, if a woman has twins, she must have been unfaithful or committed some other crime. The Sobo and Ibo customs affecting twins are not uniform. In some localities in the territory of both peoples twins are tolerated; by the Sobo of Ovu, according to Mosalo, they are even gratefully welcomed.11

It appears, then, from the preceding necessarily abridged and incomplete survey of beliefs and customs relating to twins that two contrasted and incompatible attitudes towards twins exist in Upper Guinea. These probably correspond, broadly, to two different cultures which by the movement of populations have been brought into contact. The more conservative groups holding either view concerning twins, or those between which the contacts have been less close, have, until the quite recent effective control by Europeans of the territory, retained their respective practices connected with twin bearing, while in some cases there has been a considerable modification of the views and practices in question through closer contacts of the populations holding contradictory beliefs. The humaner attitude towards twins and their mothers is more generally held the further west we proceed from the focus of practices involving the murder of twins and the death or banishment of their mothers and it is these western regions which have been most affected by southward movements of populations from the northwestern regions of the Sudan. It is probable that twin murder is older in the southward and coastal regions of Upper Guinea than the practices which cluster about the belief that twins are a benefit bestowed on man by well-disposed spiritual powers, and that these practices are intrusive from the north. Probably a more extended study of the customs connected with twins in the vast Congo region and in the south and east would strengthen the impression that emerges from what we already know about these parts of Africa, namely, that the similarities in twin-practices between certain Nigerian negroes and the Bantu would throw some light on the question of the place of origin of Bantu speech and the movements which have spread it across central and southern Africa. The situation in West Africa is peculiarly interesting and suggestive. Bantu speech reaches as far north as the Cameroons, the eastward border of the region here chiefly dealt with. Proceeding westward we come to a district inhabited by peoples speaking languages usually classed as semi-Bantu and then pass into the country near the Niger where begins the territory of the languages called Sudanese. It is among the more easterly of the populations speaking the latter languages that the practices involving twin murder appear to be most inveterate and deep-rooted—so far as western Africa is concerned. As to their eastern neighbours—the semi-Bantu speakers—we have, unfortunately, little information on the point in question. But so far as we are informed about the Bantu speakers, west, south, and east, twin killing appears to have remained one of the characteristic features of their culture. A notable exception is the Baganda, who are a mixed people ruled by northern negroids, who, like the most westerly Sudanese, do not practice twin murder.

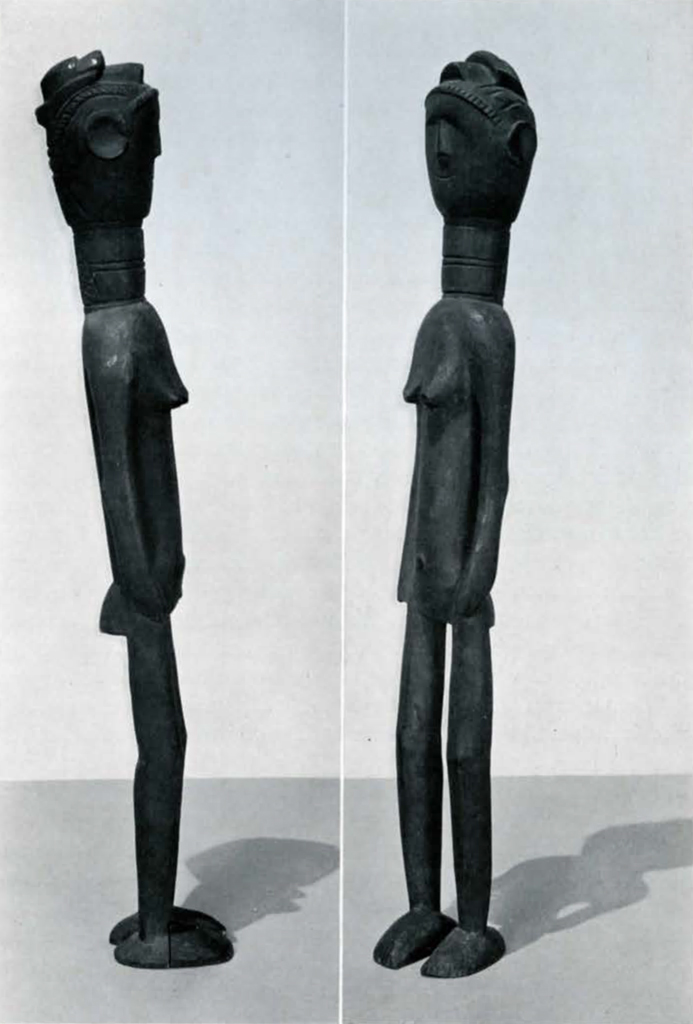

The three wooden statuettes which are pictured here on pages 405, 415, and 423 are memorial figures made each for the deceased member of a pair of twins. This custom is widely observed among the Timne, who are represented by these figurines, as well as among other groups in Sierra Leone.

As usual in the more westerly parts of Upper Guinea, twins are welcomed in Sierra Leone. Presumably because of their relation to supernatural powers they themselves and those closely connected with them are subjected to various taboos and precautionary ceremonies destined no doubt to ensure the continuance of the favour of those powers which have bestowed the initial blessing as well as to avert the dangers commonly entailed on those who enter the circle of mysterious influences which surround those who have attracted for good or ill the attention of the gods.

It is in this case, so far as our information goes, the father who is most in the eye of the gods, at least in the beginning. However that may be, we are told that in Magbile (Mabile) on the Seli River which crosses the heart of the Timne country east of Freetown, when twins are born outside the town their father’s hands must be tied for an hour. If not, the twins will not be “glad” and their parent will not get much money. When the infants are carried into the town in the ceremony which takes place soon after their birth, one of his hands will be tied again and not loosed until other twins selected for the purpose have finished building the “twin-house” which is erected on each occasion of the birth of twins. When the twins are carried round the town the father is “tied with cloth.” He gives his gown away. More naturally, it is the father who must provide whatever is necessary for this ceremony: white beads, cowries, palm oil, a fowl, cotton shirting. Beads are placed about the neck of the twins. To dream of a person wearing white beads foretells the death of a twin.

The twins are placed on a fan and taken round the town while the relatives of both parents dance round the town. On this occasion a kind of fungus that grows on anthills is mixed with the palm oil which the father has brought and the mixture is eaten by him and the mother of the twins.

Twins receive special names. Two boys are called Bali and Sine or Sana. Sometimes one is called Keru. Girls are named Seno or Suni and Sento. The child born next after twins also has a special name ‘Bèsè. For this child also the ceremonies proper for twins are performed. If all the rites are not duly performed the father or the mother will go mad. Certain “twin songs”, e.g., one commencing with an apostrophe to the twin called Bali—” Hail, Bali, hail! “—must be sung.

Twins are not allowed to eat snails or the flesh of the iguana. Violation of these taboos will cause respectively crawcraw, a skin disease, and deafness. Neither must they eat the fruit of a certain tree which is used in making the fence of the twin-house.

If one of the twin children dies, the survivor receives a wooden image which represents his deceased companion and playfellow. This image is called by a name which means “twin”. The three figures on pages 405, 415, and 423 are such substitutes or memorials for twins. If this figure is kept near the mother’s sleeping-place, the child which has survived will not fall ill. According to one account bread is rubbed on the image when the first of the pair dies. This implies that the image was made while both were alive and kept for the contingency of their separation by death. If a twin is ailing, a member of another pair gets some leaves and puts them in the twin-house. These leaves squeezed in water are used for divination of the issue of the illness. If the water is dropped on to the face of the child and runs to its nose, it will recover. When a twin dies, the survivor is washed with mafoi, a concoction of leaves which is supposed to avert or expel evil.

The twin-house mentioned several times above seems to be a form of the attatot, a word which is, apparently, applied to the miniature hut which houses charms or medicine; to a sort of woman’s secret society, membership in which is either acquired or hereditary and which is concerned with promoting the fertility of members by means of the medicine in question; and to the krifi or tutelary spirit of the society. The twin-house is put up on the right of the verandah of the parents’ dwelling soon after the birth of twins. On the fence of this miniature house are hung the rattles made of calabashes which are shaken when twins are born. Within the fence are ant-heaps covered with white cloth. These represent the krifi. The house contains potsherds, pieces of tobacco, etc. These are “twin-money”. When the twins have been weaned, they are taken by certain women—members of the society?—to the twin-house where offerings are made consisting of rice, palm oil, etc., and cowries are used for divination. Here the women and the twins eat, the twins being given whatever food they show a preference for.

When a twin who is the first born child of its mother dies, it is buried in ashes like other children, while one who is not is buried in the twin-house, if the body is small enough. Rice is offered in the twin-house, a dance is performed like that which takes place at the birth of twins, and mafoi is rubbed on the dancers.

The account of the Timne from which these details are taken says little about the powers ascribed to twins, except what is implied in the connection, itself not clear, between the attatot and the twin-houses. If this connection exists, it appears that they have an influence, as of a symbolism made effective in fact, on the promotion of child-bearing. Apart from this, they have, so far as this account shows, only the power of taking vengeance by means not explicable on natural grounds for a personal injury. Twins should not be struck on the head. If one is so struck, by anyone not himself a twin, the offender is visited at night by the injured twin, who turns the former’s face towards him as if to look in his direction. In the morning the offender will have a wry neck.12

Among the neighbouring Mendi, the twin-medicine is contained in a pair of miniature huts symbolizing twinness, one being slightly larger than the other to represent the elder of a pair of twins. The operation of the medicine is in the hands of a society, known as the Sabo, among the members of which only those who are twins are able to perform the necessary ceremonies. This is a similar condition to that which obtains with regard to the single twin-houses of the Timne and, if the attribution of a connection with these to the attatot is well founded, the activities of the twin officials are there also part of the functions of a secret society which is joined by those who wish to share in its benefits. In the case of the Mendi Sabo these include, apparently, good health and fertility for women, and the curing of the ailments of twins.13

It is clear that there is here a belief in the power of twins to promote the fertility of women. The rise of such a superstition is quite natural from the circumstances of the case, and in view of what has happened in the case of other superstitions growing out of the observed—if wrongly interpreted—phenomena of child-getting, it would be natural also if twins should be credited with being powerful to influence fertility in the production of crops. Yet there is little evidence of the existence of such a belief in Africa. There are, of course, the Baronga, on whom the learned author of The Heavenly Twins largely relied to strengthen the case for a universal belief in the connection between twins and the earth’s increase. These people attribute to twins or their mother an influence on the production of the fertilizing rain.14 A connection between twins and the rain might be, quite doubtfully, inferred from the Bakongo belief cited above that anyone who went abroad on the day of the birth of twins would meet the spirit of the waters. Similar instances are few, and instances of superstitions which seem to proceed from a contrary belief are not lacking in the not very long list of the powers directly attributed to, or implied to be possessed by, twins and their parents.

In Sierra Leone, where twins are esteemed, and where, as we have seen, their powers appear to be directed to the promotion of human fertility, we are told of the Koranko, neighbours of the Timne, that they believe that twins “have spirits behind them”, who are apparently inimical to the crops. They say that twins must not accompany people who are going to the fields to reap or thresh the rice. The reapers cut one sheaf and place it in the path leading to the village. A twin takes this and says to the spirits: “I have taken ours; those who are behind me, don’t take from the farm.” Then the crop is safe. This is in a region where twins are favoured, and it is not the only instance of a belief that twin-bearing or twins have a harmful influence on the food supply, where twins are welcomed. The Masai and some other related peoples, i. e., eastern non-Bantu, who, as well as other negroids and negroes on the northern border of the Bantu-speakers in the east, consider twins lucky, will not allow a woman who has borne twins to go near the kraal where the cattle are kept. The reason for this precaution is no doubt the same as that which causes the Wawanga of Elgon district to forbid the mother of twins to look at a cow when it is in calf ; its milk, they say, would dry up if she did. The Wawanga also hang a certain charm about the neck of a cow which is in calf when twins have been born in a village. The charm is removed when the calf has been weaned. They also take special measures to avert evil from the crops before they will allow a woman who has borne twins to take part in sowing or reaping.15

To return to the West. The Bassari of Togoland, who kill one of a pair of twins at birth, also credit a twin-bearing woman with the power to blast the crops. Such a woman must not take part in planting or harvest until she has borne another child.16

But the powers attributed to twins, even where they are regarded with suspicion, or actual dislike, are not always powers which make only for evil. In the South, among the Kafirs, where twins appear to have a connection with the powers that send the rain, it is said that people who want rain go to a twin and ask him if he feels well today; if he confesses to feeling a certain uneasy restlessness, the rain will come. Kafir twins are songmakers, receiving inspiration from a waterfall, to which they repair, accompanied by an attendant, to listen to its song. They are consulted to settle quarrels. Fore- telling not only rain, they predict, practically, also the course of epidemics: if infectious sickness attacks first a twin in the community it will spread; if the twins escape, the epidemic will not be serious. They are wild and fearless, and were formerly placed in the forefront of a battle to ensure success when the people went to war. By Castor and Pollux! Moreover, no doubt in conformity with good “Heavenly Twin” doctrine, the Balung, a Bantu-speaking people of Guinea, send their “doctors” with a pair of infant twins into the fight, when they wish it to be stopped. For here twins are said to be a blessing from Diaw, which is, according to Talbot, a name for the series of rites by which Obasse, the sky-god, is worshipped;17 and no great change beyond the addition of an -s is necessary to convert Diaw, the group-name which appears in some cases to be personified, into Dyaus, the equivalent in ancient India of Zeus, the sky-god of the Greeks and the father of one, at any rate, of the Spartan heavenly twins! This, however, is by the way.

The Bambara of the French Sudan regard twins as a benediction from their high god, the creator. They have a special twin fetish which resides in something resembling a sand-box (or hour-glass?—sablier) composed of two plaques of woven grass, between which is suspended a piece of iron or of wood with a bit of navel string wound about it. This is said to protect the mother of twins and to have the effect of uniting the latter in peculiarly close affection. It also endows the twins with immunity from the effects of bites of scorpions. The scorpion is their servant and they may send it to wreak a grudge on an enemy. The Igara of Northern Nigeria, who are said to be sprung from the Yoruba, believe that twins, while they are still young, can foretell the sex of an unborn child. By the Yoruba, according to S. Johnson, who was himself one of that people, twins “are almost credited with extra-human powers.” Johnson, however, does not specify these powers. The Hausa of Northern Nigeria are said to regard twins “with a religious awe.” They say that twins can handle snakes and scorpions without receiving injury, and can stop the boiling of a kettle by the mere exercise of will. In one respect these powers resemble those attributed to twins by the Igara, who are in contact with the Hausa and who attribute to twins immunity from poisons in general.18

The Bantu Bakongo of the Lower Congo, to whom reference has already been made in another connection, have, like many other African peoples, special names for twins. Regardless of their sex, the first born of twins is called Nsimba and the younger Nzuzi or Nzuji. Nsimba is said to have special power for dealing with spirits and Nzuzi for dealing with affairs of law.19

So much for the powers more or less implicitly ascribed to twins. There is, of course, also, the baleful contagion ascribed to twinness which seems to underlie twin murder and the murder or banishment of the unfortunate woman whom the bearing of twins stamps as a carrier of the dreaded infection; and the mysterious influence which resides in twinness, doubleness, is not, as we have seen, confined to the animal kingdom. Reference has been made to the belief of American negroes in the power of twin fruit to cause twin-bearing in women; the Kafirs assert that to receive two articles, not in succession but both together, from a twin will cause twins to be born in the family of the recipient. Animals, however, are probably more commonly the vehicles of this power. The same people say that eating mice caught in couples or eating certain portions of the kidneys, a twin organ, will have the same result.20

The making of a figure to commemorate, or to house the spirit of, a deceased twin is not by any means confined to the Timne. The custom is followed by other peoples in Sierra Leone, and by various other tribes in Africa, not only in the West and, strangely enough, not only by people who cherish twins. Among the Limba of Sierra Leone a “doll” is carved when one twin dies, and it is kept near the survivor and rubbed with palm oil and salt if the child is ill. A girl twin who has had such a “doll” made for her on the death of the other member of the pair keeps it when she is grown up and rubs it with oil when she bears a child. A fowl is killed and offered to the image on the day when the surviving child is weaned. Similarly with the Loko, an image is given to the survivor when one of the twins dies in infancy and rice is offered to it for the deceased whom it represents. Of the Bambara in the French Sudan we are told that if one twin dies in childhood, the survivor receives an image which he preserves with great care and which is named after the deceased. He dresses it and decks it with trinkets. If a present is made to him it is usual to add five cowries for the image.21

The northern Yoruba starve or poison the second of a pair of twins, and cause an image to be made to represent the dead child, so that the survivor may not feel lonely. This is the explanation offered to Meek and it may legitimately be supplemented by those given to Ellis, Talbot, and Thomas for the corresponding custom among the Yoruba of Southern Nigeria. Ellis says that “when one of the twins dies, the mother carries with the surviving child, to keep it from pining for its lost comrade and also to give the spirit of the deceased child something to enter without disturbing the living child, a small wooden figure., seven or eight inches long, roughly fashioned in human shape. . . . Such figures are nude, as an infant would be, with beads around the waist.” According to Talbot, one of the pair was thought to be non-human, and, until recently, was allowed to perish of neglect or exposure. Sometimes, if one died [sic], his spirit was believed to torment the survivor, and so a small wooden representation of the deceased was made, to harbour its spirit, and food and drink were offered to it. Meek’s statement that it is the “second” of the twins whose place is taken by an image is both supported and further explained in Thomas’s statement. The twin first born is considered the younger: he emerges first because he is sent out by his senior “to see the world.” The latter is probably Meek’s “second” twin. He is considered first in age and the apparent anomaly which gives the greater importance to a younger twin by causing him to be commemorated with an image is paradoxically explained by Thomas’s statement that it is this second, and senior, twin, who, dying, has an image made for him. The reason given was that if this was not done the mother would bear no more children.22

It seems likely that at a somewhat remote period twin murder was general among the Yorubans and that the custom was modified —indeed it was in most parts abandoned—possibly as the result of a spontaneous interior reaction against its brutality, no doubt also (or entirely) through the influence of northern invaders who held humaner views of the proper way to treat twins. The Yorubans were quite early subject to pressure from Islamized negroes, and the population has for a long time included a large number of Mohammedans. It must be admitted, though, that this suggested explanation is not altogether satisfactory, unless there is some way of accounting for the fact that it is the northern Yorubas who still persist in killing, or allowing to perish, one of the twins, while it seems on the face of it that it is they who might be supposed to have undergone the strongest alien pressure. At any rate it seems that some such reason, not necessarily including a Mohammedan factor, must lie behind the peculiar distribution of contradictory twin customs on the western border of the twin killers near the lower Niger, where we find twin killers cheek by jowl with, sometimes even in the same racial or linguistic group surrounded by, those who welcome and cherish twins.

In Dahomey, if both the twins die a pair of figures is made. These are dressed and decked with flowers and offerings of whatever is supposed to please them most are placed in a corner which is assigned to them in the dwelling. A palm oil lamp is kept burning before the figures. If the people to whom Miss Kingsley refers as the Tschwi are, as I suppose they are, the Tshi of the Gold Coast, they have in general customs very similar to those of the Dahomans. The Tschwi, Miss Kingsley says, make an image of a child’s dead twin and keep it near the survivor as a habitation for the soul of the deceased, so that it may not be forced to wander about and, feeling lonely, call its companion after it.

Weeks’s Bakongo, who starve one of a pair of twins, keep beside the survivor “a piece of wood roughly carved to represent a child,” so that the real child may not feel lonely. If this child also dies the image is buried with it. Of his (northeastern) Bakongo, Father Van Wing says: “In the case of the decease at an early age of one of the twins, its measure is taken on a stick. This stick is laid beside the survivor. When the latter is washed, the mother washes also this stick, which is looked upon by her as the brother [of the deceased]. If the survivor grows to maturity, only then is the stick-brother abandoned and hung up in the roof of the hut.”23

A very curious variety of this practice is reported from East Africa. Among the Busoga of the country near the Victoria source of the Nile the rule is that twins must not be moved from the spot where they were born nor the navel strings cut until a special medicine man has been summoned and arrives to give permission for the operation. The portion of the cord which is left attached to the infant after a time dries up and falls off. When this happens, the string of each child is wrapped in bark cloth and shaped like a doll. When the child is nursed, this crude image is held to the mother’s breast as if it too were being suckled. The cords are preserved by the mother after the children are weaned.24 In the absence of any native explanation of this custom, which differs from the others described in having no apparent connection with the death of the twins, it is difficult to relate it to these others. The Dahomans, we saw, make two figures also, but only to replace dead twins. The Bambara twin fetish described on page 419 contains a bit of navel string and is connected with the living twins, for the head of the family sacrifices to it as long as the twins live. But the Bambara make also an image to represent a dead twin, and we are not told of any relation between this and the navel string of either the dead or the living child.

In the account of Timne twins we saw that they have special names given them. Special names for twins are common in Upper Guinea, occur also in Lower Guinea (e. g., Bakongo), and are found again in the East. One of the Timne names for a boy twin, Sine, occurs again among the Bambara in the form Sinna; another, Bali, turns up again among the Yergum of Northern Nigeria, where twin boys are called Tali and Bali. Yoruba, Ewe, Bakongo, and in the East, Basabei, Busoga, Nandi, and Teso all have special twin names. The Yoruba nomenclature connected with twins is elaborate and extends even to the three children who are born successively after twins. The first born of a pair of twins is called Taiye-wo (Taiwo), “see the world”. This case has been referred to already in speaking of the arbitrary and paradoxical mode of assigning seniority as between twins. Taiwo is considered the junior, Koindi, “come behind”, the senior. The child born next after twins we have already heard of also as causing trouble if he does not succeed in getting himself born. He is Idowu, and the same name is given to no. 3 among triplets. The next is called Alaba; he is the servant of Idowu. If another follows he is named Idogbe. He watches the house when others come and is held very precious. These are the names as given by Thomas. Johnson, himself a Yoruba, uses the form Taiwo for the first born and interprets the name as a contraction of To-aiye-wo, “have the first taste of the world”. For Koindi he gives the form Kahinde, “he who lags behind”. The child following Idowu he says is called Idogbe, if it is a boy, and Alaba, if a girl. The proper attribution of these last two names is thus in doubt, unless we give the preference to Johnson’s version, as to that of a native. He differs also from Thomas in regard to Idowu as the name for the third member of triplets. This he says is Eta Oko. Ellis gives yet another twin name. The monkey, he says, which among the Yoruba is sacred to the twin god Ibeji and tabooed to twins and their parents, is called Edon dudu or Edun oriokun, and one of the twins is usually called after it, Edon or Edun. Perhaps these discrepancies really correspond to local variations in custom. At Sabongida in Edo (Benin), where we know Yoruba influence is strong, the elder twin is called Odion, which looks very much like Edon, and the younger Omo (Thomas).25

A feature which emerges very clearly from a consideration of many accounts of the treatment of twins in Africa is the conception of a kind of mystic unity in duality which the twins represent. It is probably a feature which corresponds to an early result of primitive emotional thinking about this type of abnormal births. Even among peoples who have contrived the plan of destroying twinness by killing or allowing to perish one of the pair, we find paradoxically enough a symbolical restoration or preservation of that very quality by the device of the artificial twin-figure which must be treated in the same manner as the actual living twin. It is as if they realized that this dual unity cannot be destroyed and being inherent in the survivor must continue to be represented objectively, if only by a symbol, to every one concerned, including the spirit of the deceased who will be injured and moved to retaliation otherwise.

The insistence on the importance of recognizing the essential unity in twinness, that abnormal splitting of a personality which must by every possible means be, as it were, restored when destroyed even by hostile and apparently paradoxical design, appears in many details of the behaviour towards twins besides the twin-figure contrivance. Twins, we find, must be treated exactly alike, receive the same gifts, be married at the same time, etc. An account of the life history of twins which reveals this attitude in many details and with the greatest clearness is one received from the Sobo Mosalo. It is in part as follows.

Twins are enthusiastically welcomed by the Sobo (Uzhobo) of Ovu. After a ceremony of thanksgiving at which a goat or sheep is sacrificed to the god Egyu, who sends twins as a double gift, the twins are presented to the community by the same obbo or priest who has performed the sacrifice and has prayed to Egyu that other women may be equally fruitful. All the villagers who are so disposed then bring or promise gifts to the mother. Twins must go through at the same time the various ceremonies, mutilations, etc., which accompany birth and arrival at puberty. If they are of different sexes, the boy must wait for circumcision, which is in other cases performed on the eighth day after birth, until his sister is ready for the corresponding operation which does not take place until she is considered to be of nubile age. When it is time for the children to be named, that is, when they are two or three years old, they are taken by the father to the chief, who summons the elders of the village, and the father in their presence pronounces the name which has been chosen and which must be the same for both children whether they are boys or girls.

Twins dress alike, which implies that if they are of opposite sexes the material of their clothes at least must be the same. They eat from the same dish, drink from the same cup, sleep in the same bed until they are married, if they are of the same sex; if not, in the same apartment. If they are males, they must marry sisters, or if sisters are not available in the family which is to provide their partners, these must be the most closely related girls available. The case is the same, mutatis mutandis, for twin sisters. In the case of brother-sister twins, the girl must marry the brother or the nearest available male relative of the girl whom her brother marries. The twins must live as neighbours, when married. If one of the twins now dies, the survivor is taken to the chief, who places him for a time under restraint lest in his grief he should commit suicide. When his grief, which is usually very violent, has in a measure abated, he goes home and takes his brother’s widow to wife. Marriage is here polygamous. Everything is done to obliterate as far as possible too poignant memories of the deceased. The common cup of their infancy, which has been preserved, is now destroyed. The mourner moves to another house. If his grief continues so acute that the idea of taking his brother’s widow is intolerable, both she and his own related wife are sent home to their own people. Often his own death follows shortly that of his brother, but at whatever interval this occurs both must be buried in the same grave. Sometimes the mourner goes mad with grief. In that case he is put to death—the usual fate of the insane.

A woman on the death of her twin brother leaves her husband and goes back to her own people. She should not marry again. If twin sisters have married, according to custom, brothers (or cousins) and one sister dies, the survivor leaves her husband and returns to her own family. She should not marry again. If she elects to stay with her husband, she will be disowned by her own family. A man whose twin sister dies puts away his first wife but keeps the others. The latter is the rule also in the case of twin brothers, when a surviv-ing twin sends away his own and his late brother’s first wives. Only the first wives of twins need be sisters, or closely related. The other wives need not be related.

* * * * * * * * *

Two of the figures pictured here were taken from the graves of twins. Evidently then some Timne twin-figures are not only made as companions for the living who are bereaved of their twin brothers and sisters but serve also as memorials to or companions of the dead. The two in question are the boy with the hat of European type and the slenderer of the two figures representing girls. The latter are interesting not only for the sake of the twin customs which they recall but also as illustrations of costume, if we may so call what is so scant. The coiffures are both typical of Sierra Leone hairdressing for women, that of the girl wearing the four heavy rings representing necklaces being a simplified form of the type of coiffure commonly represented on the Bundu (women’s secret society) masks. The other girl, to disguise her native charm, has only three widely spaced pairs of incisions about her neck to indicate neck rings. The lower part of the back of her head and the back of her neck show two areas of incised cross-hatching, which no doubt represent ornamental cicatrizations. The boy’s face shows formal cicatrizations also and he wears three neck rings like those of the first girl. At the back of his head also is a rectangular area simply marked with chevrons. Probably the rings were put on his living prototype because the other twin in his family was a sister and wore the common feminine ornaments. The total absence of chin in two of these figures is characteristic of the art of the region. The pointed oval of the face, with the mouth in the natural position of. such chin as the original might have been supposed to have, and the shortened appearance of the face proper are no doubt expressive of an admired racial type. It is well seen in the Bundu masks. The figure with the hat is 24¼ inches in height. The other figure from a grave is 22½ inches. The remaining female figure, the most interesting esthetically of these three rather crude productions, measures 23 3/8 inches.

1 R. K. Granville, F. N. Roth, H. Ling Roth, Notes on the Jekries, Sobos, and Ijos, in the Joural of the Royal Anthropological Society, XXVIII(1898-1899), p. 107; P. A. Talbot, The Peoples of Southern Nigeria, London, 1926, vol. III, p. 719; D. Kidd, Savage Childhood, London, 1906, p. 45; Junod, Les Baronga, quoted in The Cult of the Heavenly Twins, J. Rendel Harris, Cambridge, 1906, p. 7.↪

2 A. G. Leonard, The Lower Niger and its Tribes, London, 1906, p. 458; C. K. Meek, The Northern Tribes of Nigeria, vol. II, pp. 77-78; E. Foa, Le Dahomey, p. 225; D. Spieth, Die Ewe-Stâmme, Berlin, 1906, pp. 204-206; Kidd, p. 45.↪

3 Talbot, III, pp. 722, 725; Meek, II, p. 78; D. Van Nyendael, Sept. 1, 1702, in A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea, W. Bosman—English translation, London, 1705, pp. 445-445; H. Klose, Religiöse Anschauungen rend Menschenopfer in Togo, Globus, LXXXI (1902), g. 190; A. W. Cardinal!, The Natives of the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast, London, without date (recent), p. 27; Leonard, p. 458; S. Johnson, The History of the Yorubas, London, 1921, p. 81.↪

4 Études Bakongo, Brussels, without date, p. 25S; J. H. Weeks, Among the Primitive Bakongo, Philadelphia, 1914, p. 116.↪

5 Meek, II, pp. 78-79; N. W. Thomas, Man, 1919, No. 87.↪

6 A. B. Ellis, The Yoruba-Speaking Peoples, pp. 80, 81; Talbot, III, p. 723; Foa, p. 225.↪

7 Johnson, p. 80; Neveux, in L’Ethnographie, June, 1923, p. 137; J. Henry, Les Bambara, Munster, 1910, pp. 96-98; L. Desplagnes, Le Plateau Central Nigerien, Paris, 1907, p. 233; Junod in Harris, p. 18, pp. 26-27; J. Roscoe, The Bagesu, Cambridge, 1924, p. 26; J. Roscoe, The Baganda, London, 1911, pp. 290, 299.↪

8 Cardinall, p. 74; Kidd, pp. 48-49.↪

9 Leonard, pp. 460-461.↪

10 N.N. Puckett, Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro. Oxford University Press, 1926, p. 332: Leonard, p. 461; Talbot, III, pp. 724-726; Spieth, pp. 202-206.↪

11 Talbot, III, p. 725; p. 724; 0. Dapper, p. 309 of French translation (1686) of Nauwkeurige Beschrijvinge der Afrikaansche Gewesten, Amsterdam, 1668; Meek, II, p. 78; Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, XXVIII (1898-1899), p. 107. For Ardra, see also Dapper (French translation), p. 305.↪

12 N. W. Thomas, The Timne-Speaking Peoples, London, 1916, I, pp, 18, 88, 112.↪

13 114. T. J. Alldridge, The Sherbro and its Hinterland, London, 1901, pp. 149-152. ↪

14 Junod, loc. cit.↪

15 Thomas, The Timne-Speaking Peoples, I, p. 39; Sir H. H. Johnston, The Uganda Protectorate, 1902, pp. 878-879; K. R. Dundas, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, XLIII (1913), pp. 32-33.↪

16 H. Klose, Religiöse Anschauungan and Menschenopfer in Togo, Globus, LXXXI (1902), pp. 190-191.↪

17 Kidd, pp. 46-48; Talbot, III, pp. 729-740; II, pp. 69-70.↪

18 J. Henry, Les Bambara, Munster i. W., 1910, pp. 96-98; Meek, II, p. 79; Leonard, pp. 462-463.↪

19 Van Wing, pp. 258-259; Weeks, p. 116.↪

20 Kidd, pp. 48-49.↪

21 Thomas, Timne, pp. 112, 130; Henry, pp. 96-98.↪

22 Meek, H, p. 78; Ellis, Yoruba, p. 80; Talbot, III, p. 722; Thomas, Man, 1921, No. 85.↪

23 Foa, p. 225; M. H. Kingsley, Travels in West Africa, London, 1904, p. 324; Weeks, p. 116; Van Wing, p. 259.↪

24 Roscoe, The Bagesu, p. 122.↪

25 See the works already cited.↪