“All the Babylonians,” says Herodotus, who visited the land in the days of Artaxerxes Longhand, “have a seal and they carry a stick on the top of which is an apple, a rose, a lily, an eagle or some other figure, for they may not carry a cane or a stick without a characteristic ornament.”

The Babylonian seals in the days of Herodotus were reduced to a conical seal with a characteristic ornament engraved on the base, or to a stone mounted on a ring. The older cylinder seal was fast losing its popularity with the passing of the cuneiform writing and of the clay tablet. But in the Sumerian Ur of Queen Shubad and long after her, the cylinder seal reigned supreme, and the scenes engraved on its surface by the ancient gem cutters, are for us a pageant of the old civilization, history, religion and mythology. Ritual scenes, hunting scenes, heroic hunters, the myth of light and darkness, farming and agriculture, the animals of the field, the plants in the orchard, court etiquette and temple worship are represented on so many seals discovered in the last three campaigns, many of them beautifully cut and several bearing historical names, that they bring pleasure and reliable information to the student of Sumerian art.

I. The Banquet and the Symposium

Museum Object Numbers: B16727

Image Numbers: 8925b, 9196, 8640, 9244

The gods in heaven—or, for the Greek poet on the summit of Mount Olympus—drank the delicious nectar made of the honey of flowers and ate the ambrosia which gives immortality. Apollo played on the cithara his immortal songs, and Hephæstus moved about pouring wine. The Greek gods on Olympus had no more grace and dignity than Queen Shubad and her guests, no more elegant thrones and sideboards, no better cups than her gold fluted and engraved tumblers. Apollo’s cithara was a poor instrument compared with her magnificent harps of gold and silver inlaid with bright stones and decorated with wonderful figures in the round. Shubad had singers and servants pouring wine or water from silver jugs into gold and silver bowls, she had a silver table and silver jars. Her food was not ambrosia but substantial loaves of bread, a leg of lamb, bowls full of various delicacies. She drank through a gold pipe covered with rings of gold and lapis delicious beer from a pointed jar planted in a support between the king and herself. The beer was made from barley. A brewer from Lagash used to sell it in leather bottles of from twenty to thirty pints’ capacity. The queen had a three-pint skin imitated in silver, in which she preserved wine or a sweet liquor made of dates or of fermented honey. She used a gold or a silver strainer to catch the froth and the dregs, while filling the tumblers, and gold and silver lamps to light her banquets at dusk or far into the night. She lived well and dressed well. Her long hair was tied in a heavy roll on the neck with a silver or gold ribbon to which she might add a golden crown, a golden comb, a pair of earrings, a choker of gold and lapis, or a couple of necklaces with pendants. Her mantle of the finest woollen stuff, with long white flocks like a fleece, was thrown over the left shoulder and fixed under the right arm by a long gold pin, from which her blue lapis seal hung like a toggle. The men wore the fine woollen shawl about their loins in the Eastern fashion, the king being distinguished by a better and longer one. They were shaven and shorn, and removed their wigs, false beards and mantles before sitting at the queen’s banquet of wine. They wore big beads of gold and lapis on a gold chain about their necks and gold bangles around their wrists. These were glorious times which the gem cutters never tired of representing on the two registers of the blue lapis seals so characteristic of Shubad’s time, and which disappear with the passing of her golden age.

Museum Object Numbers: B16828

Image Numbers: 8929a, 9203, 8925a, 9195, 8928a, 9202, 8926b, 9199, 9243

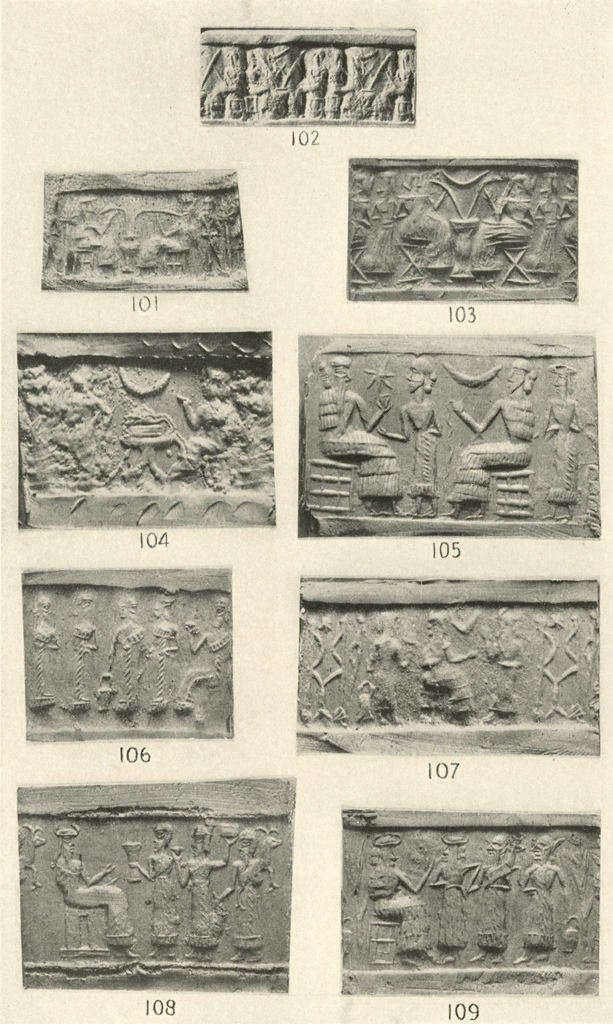

The queen’s banquet was no simple human feast, but a solemn ritual banquet, worthy of being represented many times on the big lapis seals, as the best symbol of peace and abundance in the land. No god, in this remarkable period, was yet represented under a human aspect. Mythology was still playing with animal forms, and was giving them by degrees the human attitude, arms, and face. The divine power was then all invested in the king and queen, the high priest and priestess at Ur. When the gods later copied the royal style and borrowed crown, sceptre, and throne, the high priestess at Ur never ceased to be on earth the living Moon Goddess, sharing the golden bed of the god on the top of the tower and listening to his oracles in the night. The royal banquet of meat and wine became a regular sacrifice of food and drink. It was offered to the gods and disposed of by the priests. A solid altar of clay or bricks with a ledge replaced the elegant sideboard or cane altar of Shubad’s time. It was planted before the god, like the low offering table, and was no longer carried about by a dog in the character of a butcher playing the part of a sacrificer, assisted by a lion-butler. The priests had developed into regular servants of the god. The golden pipes were no longer, or very seldom, used for drinking the sacred beverage. Instead of these, the libator poured a thin stream of water on green palms and bunches of dates in a vase placed before the god. Water is the life of plants, food and drink are the support of human life. The old banquet scene has its full significance in all religions, figuring the longing for life and the eternal cup of joy. The servants of the king became priests of the god. They used in their ritual the same spouted jug. They learned to cover their nudity, but their bald clean-shaven heads always marked them as slaves to the god, their master. The harps and the cymbals were not forgotten, but they no longer added to the royal pleasure or supported the recital of heroic deeds. In the courts of the temple they accompanied prayers and the singing of psalms. As a pious offering Gudea presented to his god a sounding harp and a state chariot. He had a limestone plaque carved in relief, like the one in the Museum, a memorial of his splendid gifts. Dresses also became more formal.

Image Numbers: 8928b, 9204, 9210, 9211, 8924

A true horned mitre, first with one, later with four pairs of horns, was devised as the proper headdress of the gods and of their attendants. Temple etiquette replaced the beautiful simplicity of old, when Queen Shubad tied her black hair with a golden band, or on feast days with strings of beads and floral ornaments of gold. While the king and his men had made themselves comfortable by removing their wigs and their beards, the gods now thought it below their dignity to appear without formal beards and long tresses of hair hanging down the back or tied up on the neck like a chignon, or in a heavy roll confined in a net. Dresses followed the common fashion. Pleated robes of linen, fringed and embroidered shawls of wool replaced the old kilt of kaunakes or the shawl of the same material, which the queen wrapped about her left shoulder and fixed below the right arm with a long golden pin.

Museum Object Numbers: B17033 / B16863

Image Numbers: 8928, 9205, 9206, 9209

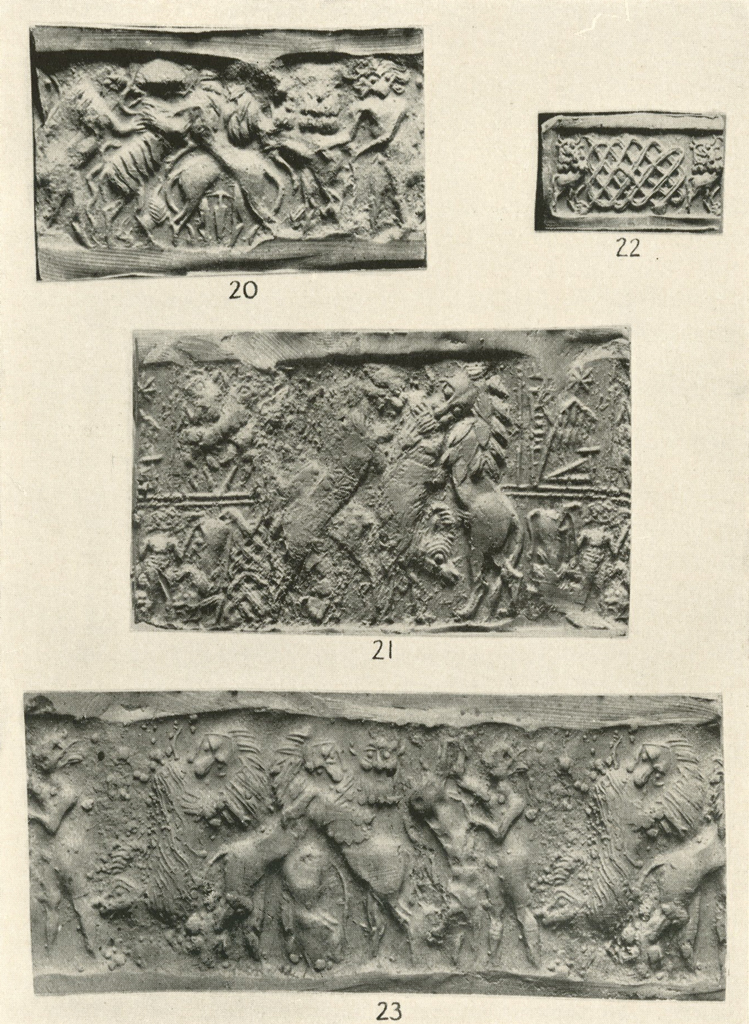

The human faces on the blue lapis seals are poor examples of the engraver’s art. They are reduced to a bald head with prominent nose and a large eye, which give them a bird-like aspect. The rendering of fine details is not easy in the soft lapis, and the gem cutters were mainly interested in the ritual meaning of the scene. Primitive artists, as a rule, are better at drawing animal figures than at sketching human forms, as will appear in the next wonderful series of seals. The small scenes engraved on the seals derive their inspiration from larger works of art like the inlay stela where eight persons are seated at the royal banquet of wine with songs and music. The eighth and last figure, isolated in the upper left corner by a gap in the mosaic, and, like the king, attended by a special servant, is probably the queen, the high priestess. The long lines of animals brought as offerings, and the gift carriers shouldering their burden, picture the abundance of peace time. The same servant carrying a sheep by neck and tail is found again on a lapis seal. The lamb or kid brought in the arms of the worshipper is a picture of all times. The three goats are found on many seals and plaque reliefs. The first has spiral horns and pendent ears, and is followed by two others with curved horns and ears erect. Their goatherd drives them with stick or whip. The inlaid stela with its scenes of peace and war is the oldest of a long series of memorials, like the stela of the vultures, down to the black obelisk of Shalmaneser. It is a monument to the victorious king of the old city-state. But the animal figures and the hunting scenes on the triangular ends of the inlay stela, and on one register, if not on two, of many lapis seals have a more primitive character than the war and banquet scenes. They are an echo of that legendary past when all animals and all plants were wild and when Gilgamesh the hero-hunter fought with the bison, the leopard, and the lion. The old heroic figures, modified with time, never lost their popularity to the end of Babylonian history.

Museum Object Numbers: B16747

Image Numbers: 8640, 9239

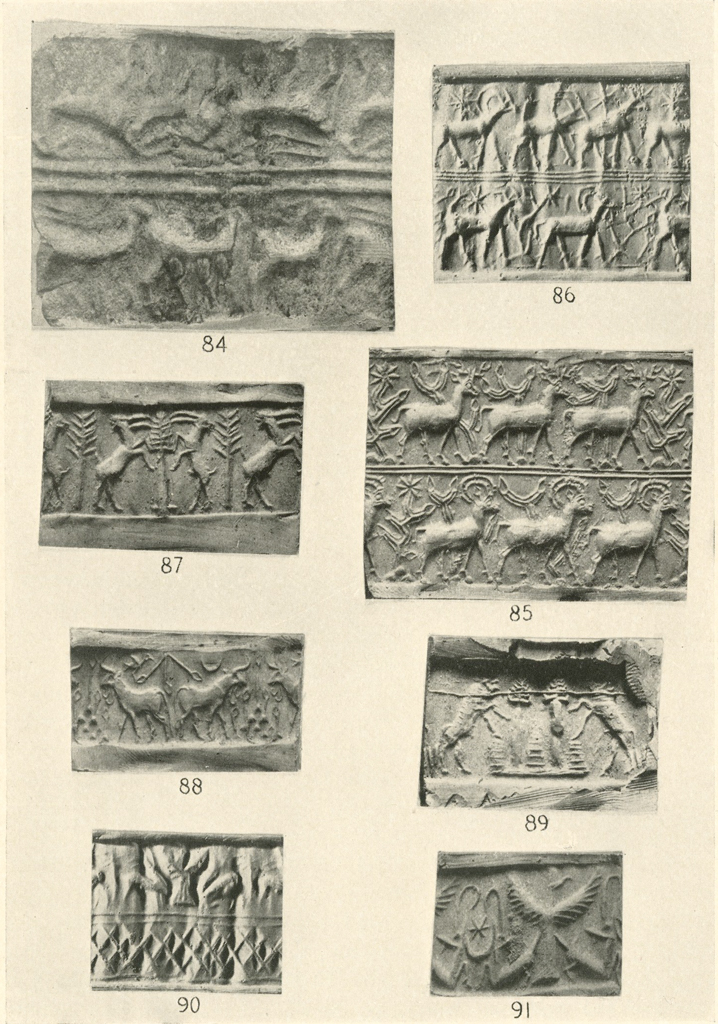

Out of this rich fund of hunters’ legends and characters, the old gem cutters selected as an alternative to the banquet and symposium a few scenes of animals crossed, rampant, or couchant, fighting or dominated by a spread eagle, or attacked by a standing or kneeling hunter. The spread eagle, not flying but seizing its prey, is a classical figure of complete possession and triumphant power, which needs no comment in a country where they still train hawks, falcons, and golden eagles to hunt wild fowl and other game. The same symbol with the same meaning still decorates modern standards. The kneeling hunter is a rarer and more interesting figure. He has one knee on the ground and one raised to steady himself while capturing an animal from behind. On old Elamite seal impressions he is armed with bow and arrows and his position is perfectly clear. On the lapis seal he closes on the animal and grasps it by tail and leg. A dagger seems to be his only weapon. On the gold diadem published in the Museum Journal for December, 1928, on page 380, he is attempting to catch a bearded bull. But the method adopted is not obvious. He may be using a snare or trying to cut a tendon. The kneeling figure is found again, this time with a rope in his hands, in another series of scenes which may throw light on the subject. A tame or captured bull is lying down peacefully chewing its cud. Above a gate adorned with a pair of wings is the emblem of the park closing on the cattle, as the eagle’s grasp closes on its prey. The rope held by the kneeling hunter or keeper is attached to the gate. A second rope is held in the same manner by a seated goddess, mistress of flocks and herds. Corrals and nets to capture wild animals are the origin of the farmer’s parks and pens. Such is the picture drawn for us by the old gem cutters of Shubad’s time.

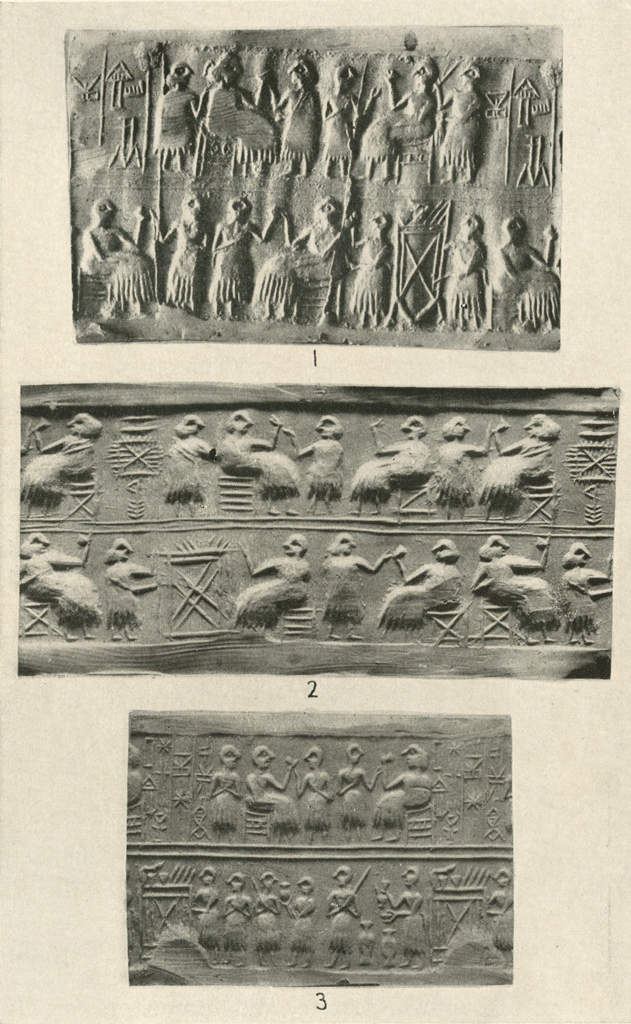

- Lapis seal of Queen Shubad with her name engraved in linear characters. Banquet of wine and meat. This seal (U 10939), which belongs to the British Museum, and two other lapis seals of the queen are described in the first article in this number of the Journal.

- Lapis seal of Abargi, possibly the son of Shubad, with his name in linear characters. The seal was found above the wooden wardrobe in her tomb. Banquet of wine and meat. Loaves of bread on the sideboard. U 10448, CBS 16727.

- Lapis seal of He-kun-sig, a priestess of the divine Gilgamesh, with her name in linear characters. Banquet of wine in the upper register. The elegant thrones are again those of Shubad and her partner. Sideboard loaded with cups, bread, and meat, in the lower register. Vergers with staff of office introduce choice drinks. A servant holds a jug with a spout, and a saucer. Two pointed jars on a support. U 9315.

- ls, fields, and a temple of the divine Gilgamesh are noted in business documents.

- Lapis seal. Banquet of wine and meat. Loaves and leg of lamb on the cane altar. U 8615.

- Lapis seal. Banquet and symposium. Four drinking tubes in a jar on a support between king and queen. Sideboard as above. U 10823.

- Lapis seal. Banquet and symposium. Four drinking tubes and a central rod in the jar on a support between the two partners. The cane altar again rests on bull’s legs like that of Shubad. U 7985.

- Lapis seal. Banquet and symposium. Two drinking tubes and a central rod in the jar on an X-shaped support. A servant brings two more curved tubes. Meat and cups on the sideboard. A servant carries a sheep by neck and tail. U 8367.

- Lapis seal. Banquet and symposium. Four drinking tubes and a central rod in the jar on an X-shaped support. U 8119.

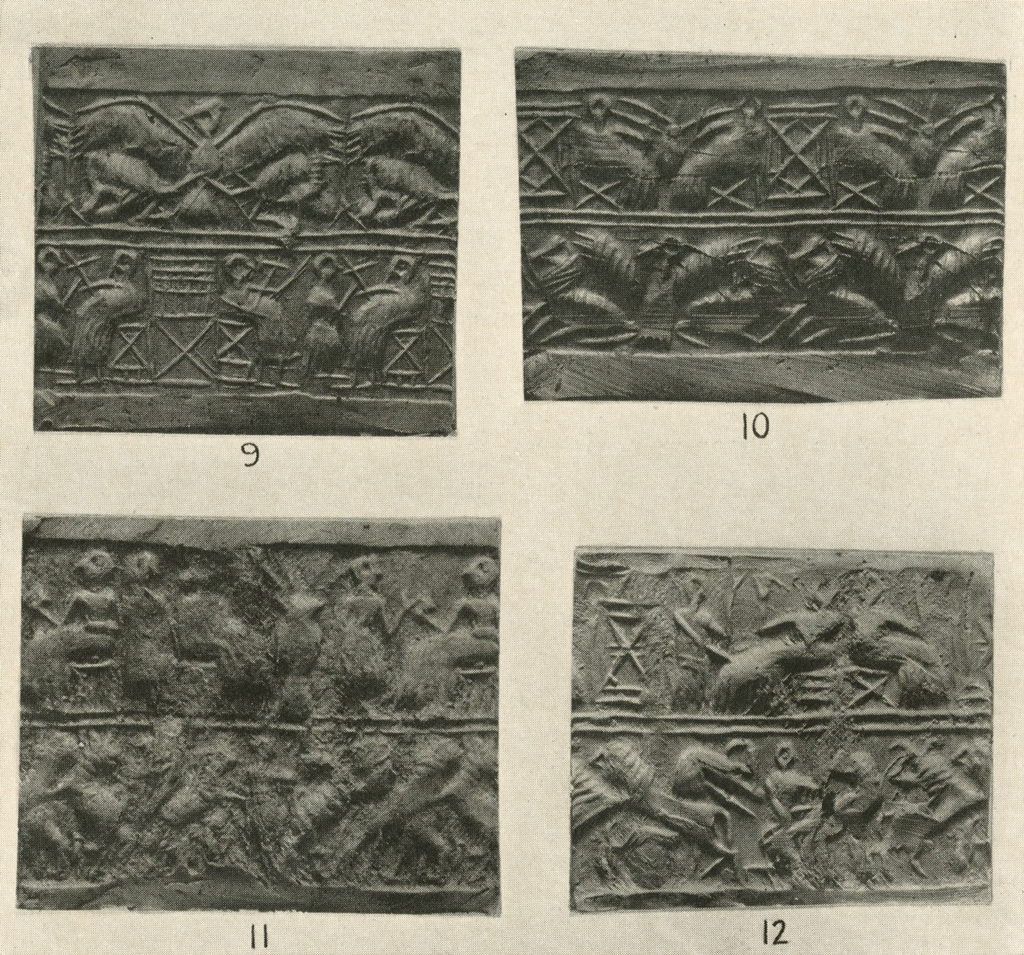

- Lapis seal. Spread-eagle over crouching goats with their heads turned, and banquet scene. The eagle has palmlike wings and head in profile, in contrast to the lion-headed eagle of the harps with its face turned to the front. The sideboard has a new shape. Its upper part is like a grating. No food is visible on it. U 8656.

- Lapis seal. Symposium and spread-eagle over crouching goats. The sideboard differs still more from the old model, and is empty of provisions. Spread-eagle as above. With the introduction of animal scenes, the banquet loses some of its interest, and is treated summarily. U 8461.

- Lapis seal. Symposium and hunting scene. Four drinking tubes in a jar on a support. The sideboard has disappeared. Two lions crossed and rampant attack a bull and a lion. A nude hunter armed with a dagger takes part in the fight. U 8792.

- Lapis seal. Banquet of wine and meat. Usual sideboard with loaves and leg of lamb. Hunting scene. Crossed lion and oats. A kneeling hunter attacks a bull. U 8643.

- Lapis seal. Banquet and symposium. Regular sideboard with loaves, meat and cups. Two drinking pipes and a rod in the jar on a support. Two bulls are lying in pastureland on either side of a bush. A rampant lion attacks one of the bulls and is attacked in turn by the cowherd armed with crooked club and dagger. A seated figure and a servant complete the picture of pastoral life. U 8085.

- Lapis seal. Hunting scene. Crossed lions, bulls, and goat. Hunters with daggers kneeling and standing. A scorpion. Clumsy symposium and banquet scene. Two pipes in the jar and only one drinker. New model of sideboard with cups. U 10822.

- Lapis seal. Only hunting scenes. Lions over goats, the latter with heads down. Hunter with dagger. Scorpion. U 8714, CBS 17033.

II. Hero-Hunters

Museum Object Numbers: B16869

Image Number: 8927a, 9198, 8928b, 9204

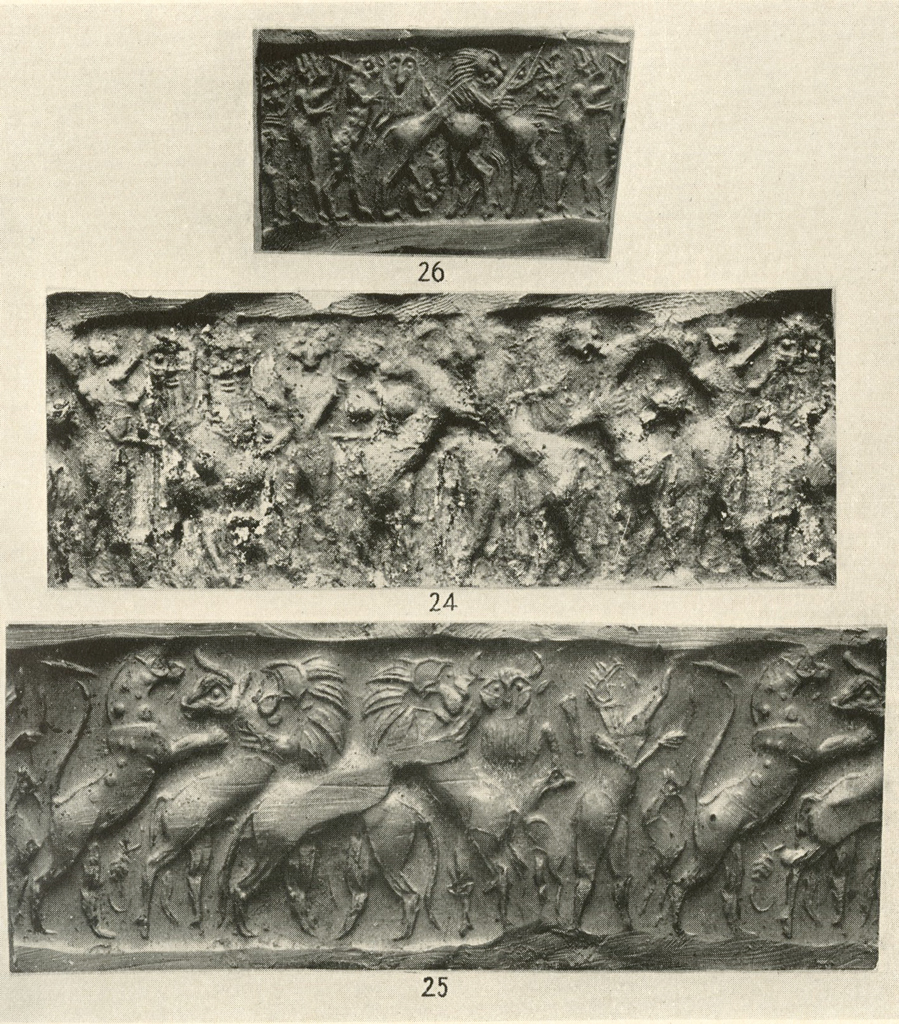

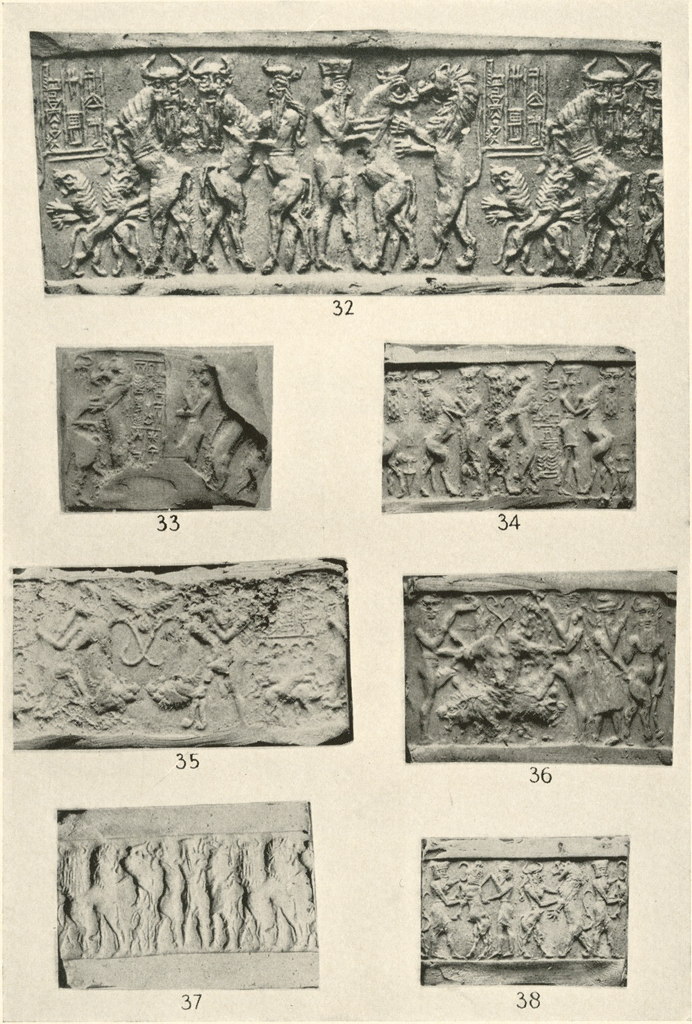

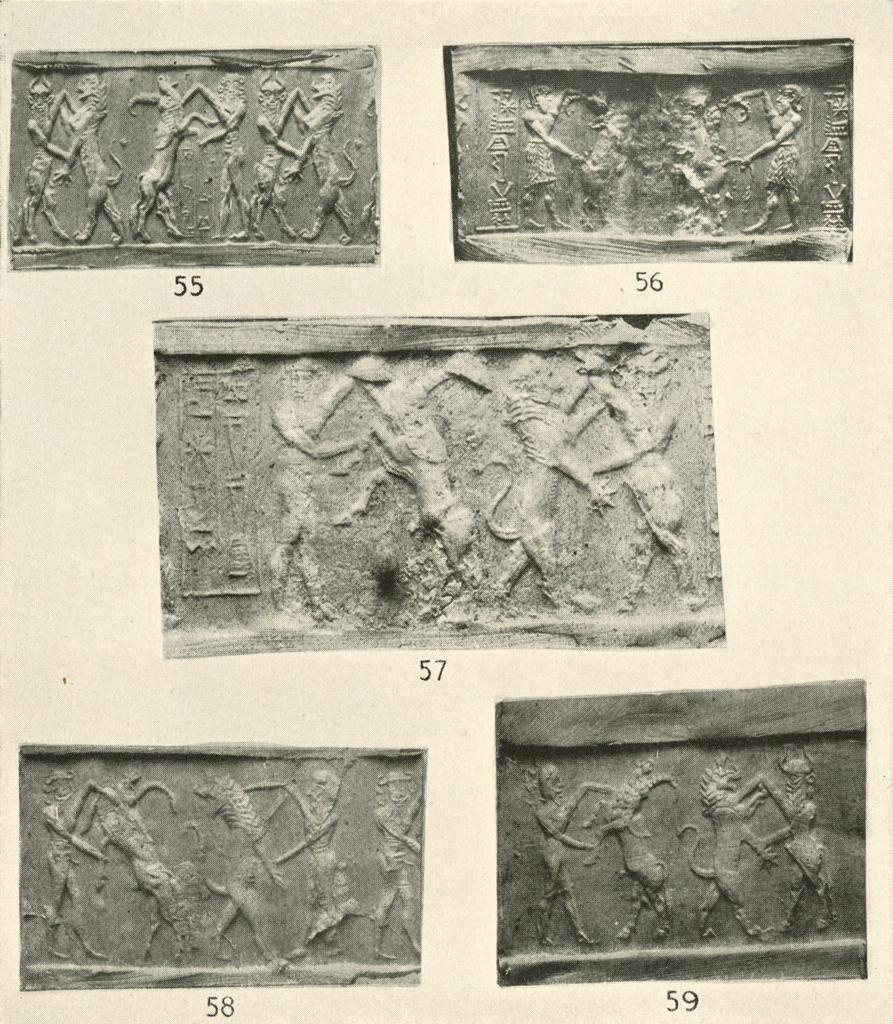

The beautiful seal of d Shara-ligir(?), the scribe of the queen—dupsar-nin–opens the series of heroic hunting-scenes. The subject is one of the most popular from the days of Shubad to the time of Mesannipadda, the first king of Ur, according to the official list of kings. But the gem cutters of Shubad were by far the greater artists. Their first clear, large, and deeply engraved composition was copied later with decreasing energy and artistic power. On the seal of Nin-tur-nin, the wife of Mesannipadda, it is reduced to a poor sketch of small crowded figures. Even the clear linear writing of old becomes uncertain. The age of Sargon of Agade will bring about a revival: new figures, clearer composition, firm cuneiform writing. These will form a new chapter: the Gilgamesh contests.

Image Numbers: 9216

But here, as in the previous series of seals, there is still a natural grace, half-way between the realistic hunting scenes of Elamite inspiration and the classical compositions of the time of Sargon. The Elamite hunter is armed with bow and arrows, spear and hatchet. He chases the boar, lion, and ibex with a pack of dogs. He shoots standing or kneeling. The symmetrical heraldic composition of animals rampant, crossed and reversed belongs to Sumerian art. The Sumerian hunter triumphs in a fight hand to hand and uses the weapons of the inhabitant of the plain, dagger, club, and spear (Museum Journal, Dec., 1928, p. 387). He is nude, with his head in profile. His wild locks are drawn in the same manner as the hair of the ram, or ibex, or as the mane of the lion. He is clean shaven, and does not put on a beard while hunting. Even when represented in full face he lacks the formal beard of the classical Gilgamesh. The types of Gilgamesh and Enkidu were well known and finely engraved on the shell plaques of the harps, but were not all-prevailing. Here again the gem cutters are inspired by larger works of art, but with a style of their own. Nearly all their motives—lions, leopards, attacking bulls, goats, rams, ibexes, deer, the bearded bull with face turned to the front, the bull man Enkidu, the scorpion, and the snake—are found on the shell plaques decorating harps and gaming boards. But the hero is still the young human athlete attacking the lion, with the very dagger of Meskalamdug, or the leopard with the dagger and club. A net spread vertically is his new device for catching lions and bisons, a very interesting forerunner of the relief on the Mycenæ gold cups.

The first four seals of the series are probably cut by the same artist. Three are inscribed. The second, a shell seal bearing the name of Lugalshagpadda, was found in the grave of Queen Shubad. It belongs to one of the grooms. Whether it gives a clue to the name of the queen’s husband is not quite certain. Numbers five and six of the series belong to the same school and have the interesting representation of the net. It is tempting to see in the inscription Gig-hu-lugal, “the royal eagle”, another royal name.

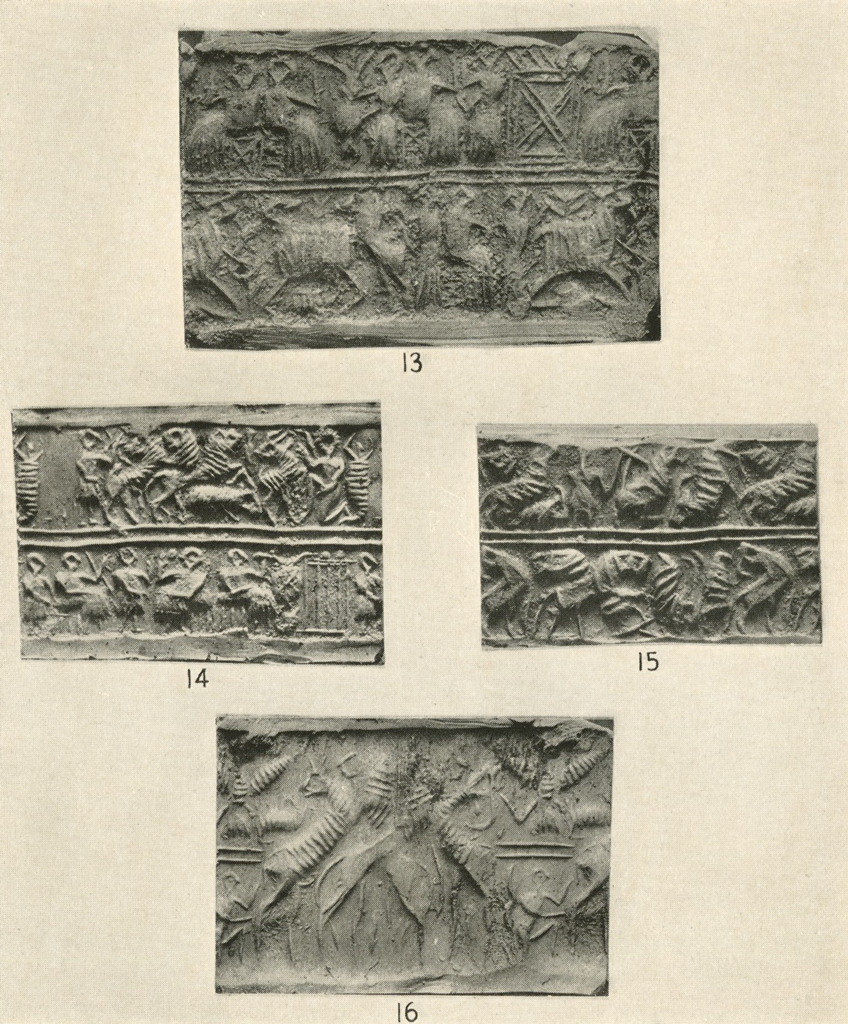

- Seal of d Shara-ligir(?) scribe of the queen. Rampant crossed lions attacking bull and upturned ibex—or ram? The nude hunter pulls one lion by the tail and strikes it with his dagger in the neck. His dagger is a copy of the gold dagger. Below the inscription, a leopard and a lion attack an ibex and a deer. Two crossed bearded bulls, the so-called man-headed bison, stand beside the inscription. U 9943.

- Shell seal of Lugalshagpadda, groom of the queen. Lions attacking an upturned ibex—or ram?—and a deer. The nude hunter with the gold dagger is beautifully modelled. A scorpion in the field. U 10530, CBS 16747.

- Seal of E-zid. Lions attacking an upturned goat with spiral horns and long hair, and an ibex with curved horns. Bull-man Enkidu with head in profile and holding a lance(?) with buckle. In the field a small upturned lion looks like a scorpion. U 11174.

- Lions attacking a long-haired wild goat and a bearded bull. The hunter, with face turned to the front, is a Gilgamesh without beard. In the field a snake, a scorpion, a crouched goat, a dagger. U 11175, A.

- Seal of d Gig-hu-lugal. Lions attacking an upturned goat—or a ram(?)—and a bull(?) In the field two small crossed bulls. A Gilgamesh without beard lifts by the hind legs two lions caught in a net. U 8513, CBS 16869.

- Net and bearded bull. U 11175, B.

- Lions, upturned goat—or ram(?)—and bearded bull. The hunter lifts a spotted deer(?) by the hind legs. U 8141.

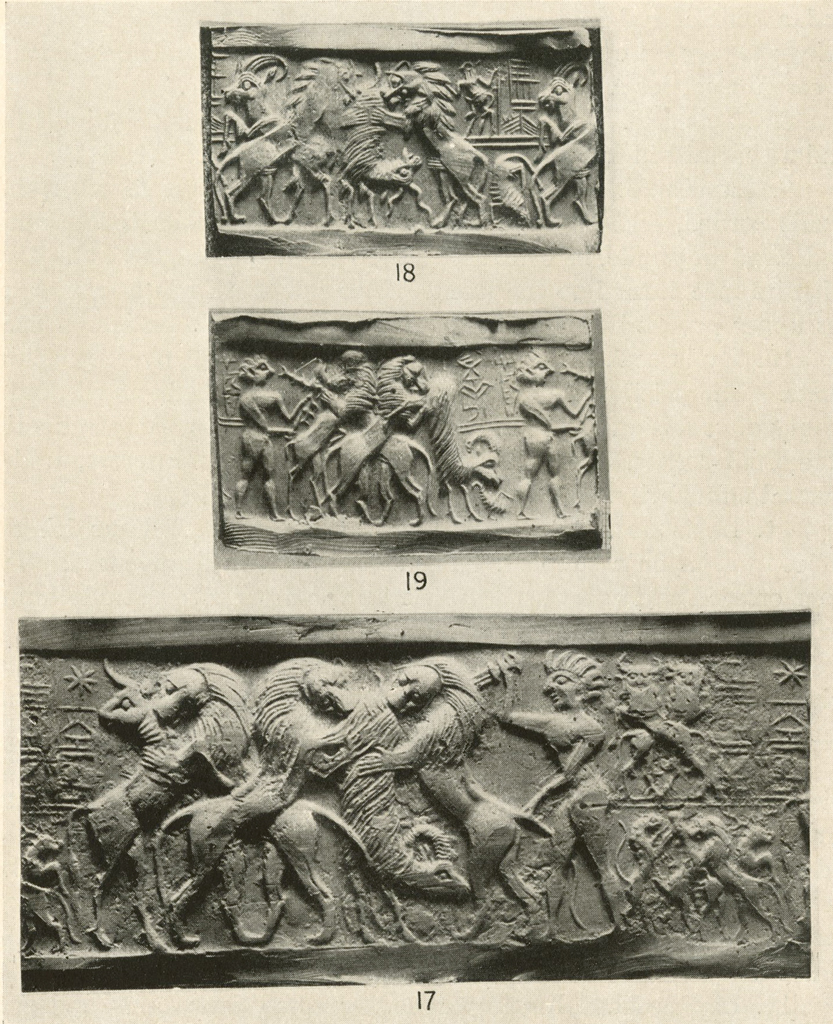

- Lions, bull, goat, and bearded bulls. Two nude hunters, one in profile and one full face. U 9187, CBS 16871.

- Lions, leopard, bull, and bearded bull. The hunter is armed with crooked club and dagger. In the field a scorpion, two rampant gazelles, and an ibex. Also a quiver(?). U 7992.

- Lion, leopard, bull, and bearded bull. Nude hunter with dagger. In the field a scorpion and a small lion(?). U 9027.

- Lions, bulls, ibex, nude hunter with dagger. U 8494.

- Lion, bull, nude hunter with dagger. A second group is formed of a bearded Gilgamesh with face turned to the front protecting a bull attacked by a leopard, which is attacked in turn by Enkidu. The bull-man is in profile, armed with a dagger. A long tress of hair falls down his back. We are on more legendary ground. U 9023.

- Seal of Arad-d Bau, probably at the time of Nin-tur-nin. Two registers of small crowded figures. Enkidu between two bulls attacked by a lion, which is attacked in turn by a nude hunter. In the lower register two crossed lions attack a bull and a deer. The nude hunter has caught an ibex. U 8359.

- Lapis seal of Nin-tur-nin, wife of Mesannipadda, the first king of Ur recorded on the royal lists. Two registers of small figures. Gilgamesh(?) with face turned to the front between a bull and a goat attacked by two lions. Below, two crossed lions attack a deer and a goat with spiral horns. The nude hunter armed with a dagger helps in the fight. U8981, CBS 16852.

- Two registers of small figures and emblems which announce the next or Sargonid period. In the upper register an ibex is attacked by a lion and a nude hunter with short hair. In the parallel group the nude hunter has the long tresses of Enkidu. In the second register the nude hunter wears the beard and the flat cap characteristic of the Sargonid period. Three lions attack two ibexes. In the field a crescent, a scorpion, a club or spear. U 9081.

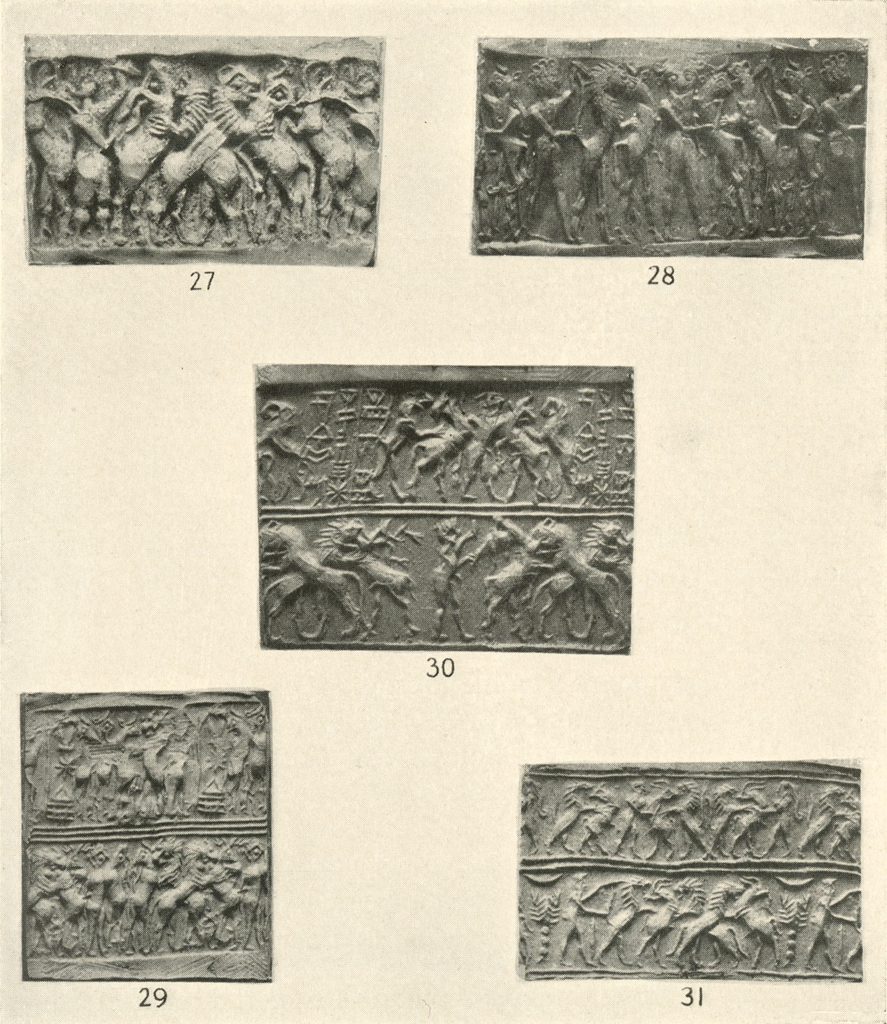

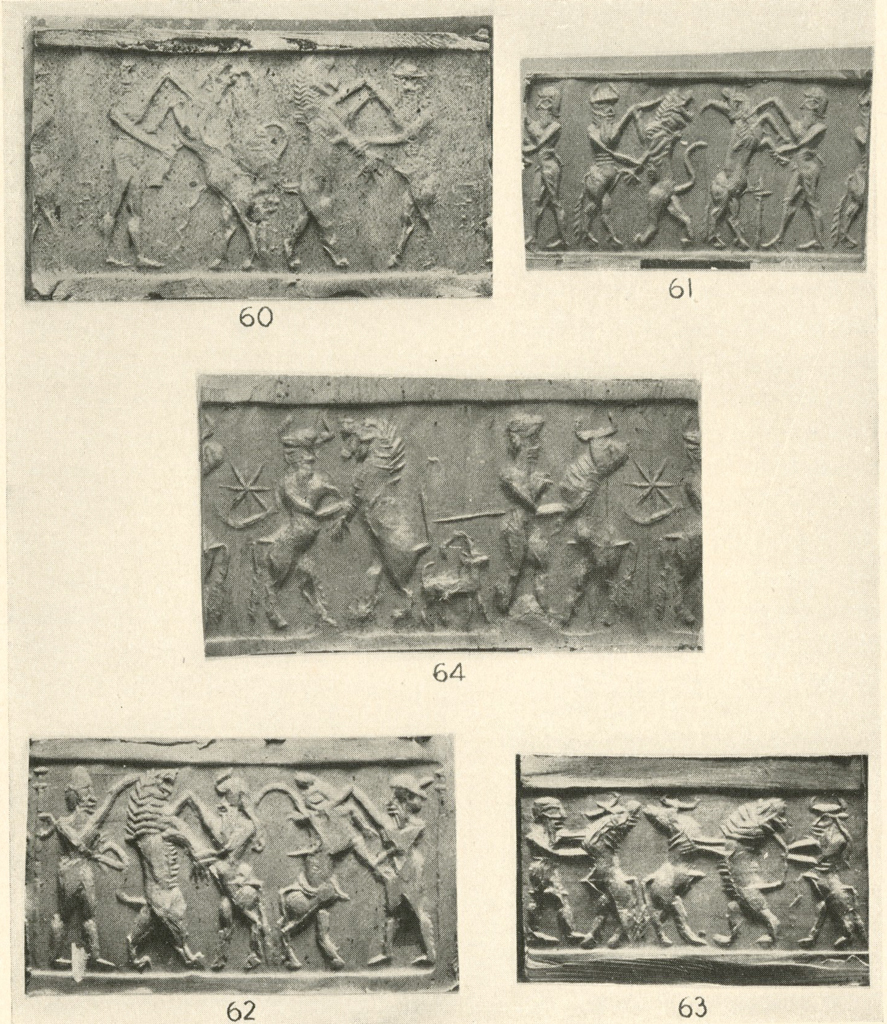

III. Gilgamesh Contests. The Sargonid School

Museum Object Numbers: B16852

Image Numbers: 8929a, 9203, 9209, 9215, 8640, 8641, 9216

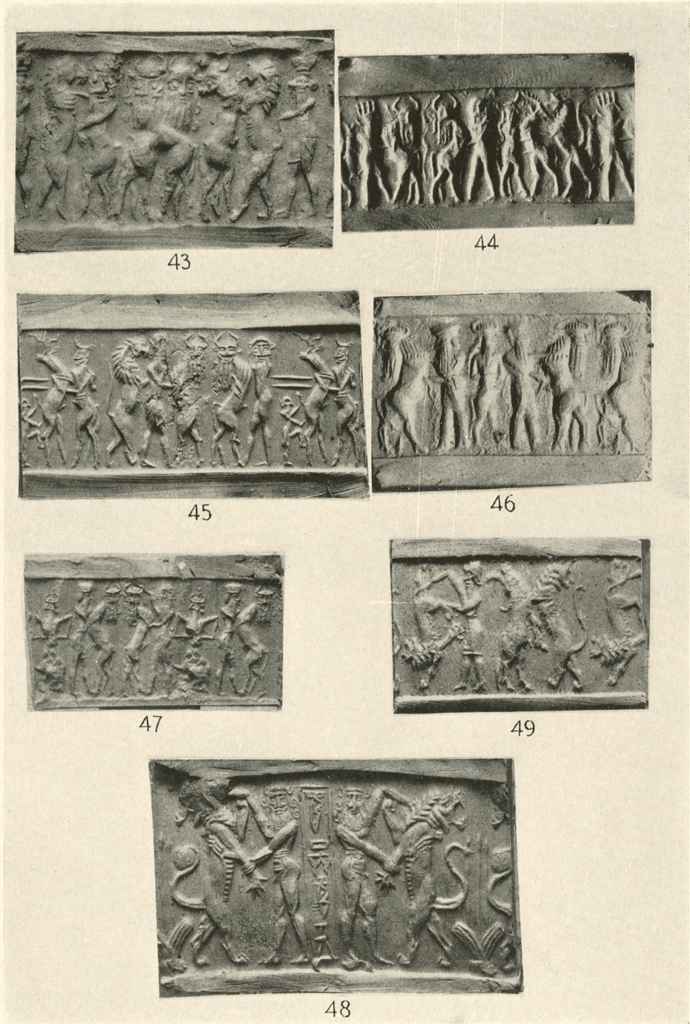

The seals confirm the great importance of the reign of Sargon, king of Kish, founder of Agade, and of the Akkadian empire from the Taurus to the Persian Gulf. There is a new spirit in the land. The Akkadian are Semites. From their northern capitals Kish and Agade, new influences and inspirations spread over the Sumerian south.

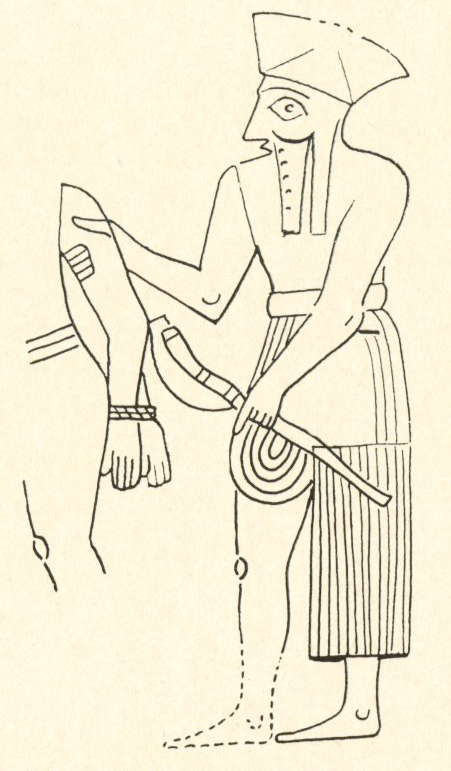

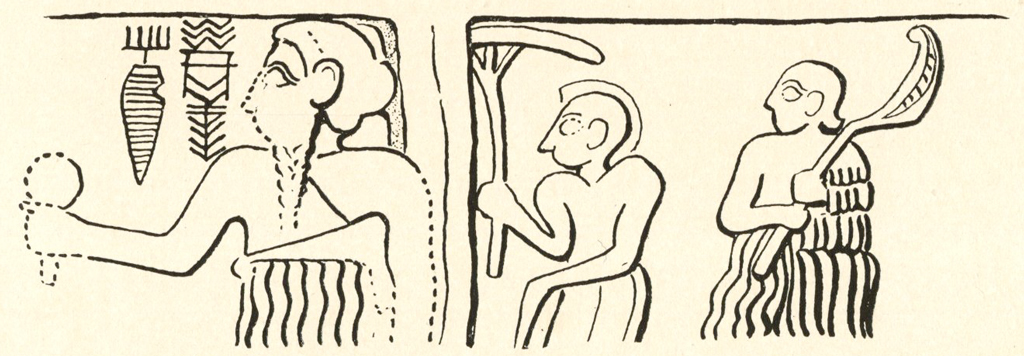

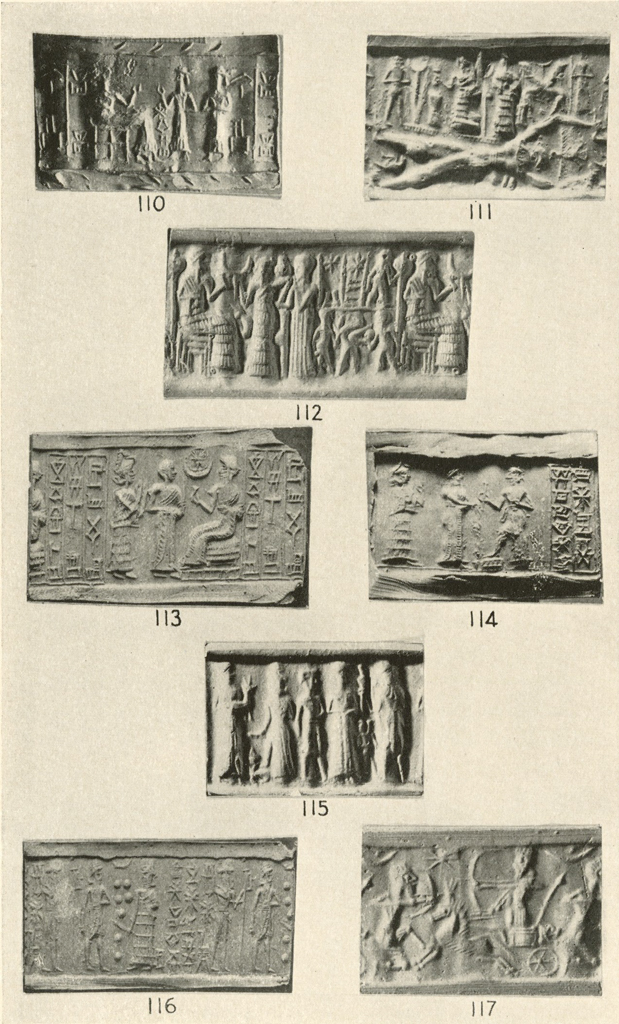

Enhedu-anna, Sargon’s own daughter, was made high priestess at Ur, and brought with her the style and fashion of Kish. We have a charming memorial of her, a disk of alabaster, pale, translucent, and round like the full moon. It was found in the court of the high priestess’s palace at Ur. Her name is engraved on one side. On the other she is represented presiding at a libation poured by a priest in front of a stepped pyramid (Museum Journal, Sept., 1927, pp. 237-239). The scene belongs to the old Sumerian ritual with new Akkadian notes. The shorn priest holds by the foot the traditional jug with a spout, over the hourglass-shaped vase, but he is no longer entirely naked. The high priestess wears a long tunic of fleecy kaunakes, instead of the loose shawl thrown over the left shoulder. Her long hair falls down her back, but three braids, in the best Kish style, play along her cheek and rest on her breast. Instead of the gold band, the crowns with gold flowers and gold rings, she has tied about her head a diadem made of a rolled scarf. The mode will continue for many centuries. The stepped pyramid may be the smaller construction existing at Ur before the great stage tower of Ur-nammu. But the whole composition has a simplicity and elegance properly Sargonid. “Each figure is drawn separately with a complete value of its own on an open field, but is connected by gesture or attitude with a single religious action.” The proportions are natural and lack the clumsiness of some of the later Gudea statues.

Besides the alabaster moon memorial, two seals of Enhedu-anna, one of her major-domo, the other—unfortunately broken—of her son(?) or minister(?), confirm the Akkadian influence of the new Sargonid school in the art of gem cutters. All have the same simple and clear composition, and avoid crowding or the crossing of too many figures. Instead of the Sumerian inlay stelæ with their large pageants, strangely alive and rich in details, the new ideal is that of the sculptor: a few figures in strong relief.

Image Numbers: 9218, 9233, 9236

The old heroic contest with wild animals is still the most popular subject, but with a marked transformation in the character of the hunter and the choice of the animals. The leopard disappears. The deer is very rare. Mountain goats, ibexes, moufflons are seldom represented, and on a diminutive scale. The Akkadian of the plain is not familiar with the Elamite hills. The bison is replaced by the water buffalo. The legendary bearded bull of the time of Shubad, with a false beard tied under its chin, gives way to the inhabitant of the marshes, with the rugose, slanting horns. The so-called human-headed bull disappears. Its front face is given to the bullman Enkidu fighting with the lion. The older Enkidu had a profile head and fought not only with the lion but with the deer, the ibex, and the bearded bull. Gilgamesh full face with the classical three rows of locks and a formal beard is henceforth the prevalent figure. He is nude and wears a triple belt. The old hunter, nude like Gilgamesh, but with his head in profile, beardless and surmounted by wild locks, the Sumerian hero who attacked wild animals with club and dagger, is supplanted by the Akkadian hero, the man of Kish, distinguished by his flat cap, beard, hair on the neck, head in profile, belt and short loin cloth, embroidered and opening at the side. He is a sure index of Sargonid time and deserves careful study.

Museum Object Numbers: B16874 / B16864 / B16875

Image Numbers: 8927a, 9198, 8640, 9216, 9233, 9237

The hero of Kish with flat cap, long hair, beard, and loincloth is represented on larger monuments, and copied by the gem cutters. On the inlay panels of the time of Shubad, or slightly later, found at Kish, his loincloth is a regular pleated kilt, opening below the sporran, with one corner raised and tucked into the belt to leave the right leg free. The hero of Kish holding a nude prisoner—wearing only a belt and with hands tied behind his back—has the same flat cap, beard, and long hair as the hero grasping a bull on the seal of Adda, the major-domo of Enhedu-anna. Only the kilt has changed with time. The long pleated garment falling to the ankles is reduced to a plain short piece not covering the knee. The sporran is no longer used. The new loincloth has embroidered edges opening at the side. It was worn early in the south (Museum Journal, Dec., 1928, p. 386, No. 16). On the Kish panels the hero is armed with a remarkable battle-axe, seen again in the hands of Sargon’s bodyguards on a stela from Susa (Revue d’ Assyriologie, vol. XXI, pp. 65-74). The handle is a curved piece of wood, to which a crescentic copper blade is attached by rivets and bands. Such blades with rivets and gold bands were discovered in the Ur cemetery. Sargon’s guards wear the short loincloth, which with the cap, beard and hair distinguish the new hero from Gilgamesh and Enkidu. He is a product of the Sargonid school, and a landmark of art. Even on the old inlay stela, the servants with short beards and plain loincloth embroidered only on the edge, may represent the early Semitic Akkadians, mixed with the Sumerians.

A few mythological figures are added to the hunting scenes: the Sun God rising over the mountains, the god of light fighting the power of darkness, the goddess of vegetation bristling with ears of barley, the hero Etana raised to heaven on the pinions of an eagle. They are the poetical expression of a natural philosophy, which will develop into formal ritual and theological teaching in the various temples from Sippar to Eridu. In the new empire the temples are gaining power, while the legendary hero-hunters recede into the past.

- Black and white granite seal of Adda, major-domo (pa-é) of Enhedu-anna, high priestess, daughter of Sargon. The Kish hero grasps in his arms a bull attacked by a lion. He is armed with a dagger(?). So is Enkidu attacking a bearded bull. Enkidu is still in profile. He and the legendary bisons wear a belt. Two crossed lions. U 9178.

- Fragment of a seal. Kish hero, lion, crossed bisons. The inscription reads: Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon; d Igi-du . . is thy . . . (son, or minister?). U 8988.

- Seal of Enki-endu, the scribe. The Kish hero and Gilgamesh fighting with bearded bulls. Both wear the same flat cap, a loincloth, and a belt, and grasp the handle of a short club or axe. The legendary bulls wear a triple belt. Enkidu and the lion. In the field a dagger. U 9764.

- Second seal of Enki-endu, the scribe, perhaps of Enhedu-anna. The third line of the inscription is not clear. A new favourite and daring composition represents a pair of athletic Gilgameshes stepping on the necks of two lions which they lift by the hind legs. The helpless lions turn up their heads, roaring, ready to bite. A spread-eagle has caught their crossed tails in its claws. The whole forms a happy symmetrical motive, characteristic of the Sargonid school. Two crossed ibexes. U 9765.

- The Kish hero and Gilgamesh tread on the necks of uplifted lions. The hero wears his usual flat cap and loin cloth, and Gilgamesh only a belt. The lions are back to back. Their lashing tails are crossed in the air. The seal is beautifully cut, probably by the same artist as the preceding, and has the same symmetry and energy of composition. The heads of the lions are a masterpiece.

Museum Object Numbers: B16880 / B16877 / B16870 / B16857

Image Numbers: 8925b, 9196, 9209, 8640, 9231, 9236, 9237, 9244

A second scene, the undoing of Enkidu, is an amusing episode of the solar mythology. A hero of light with flaming wings pulls by horn and tail the unfortunate Enkidu, who protests in vain. The fight is over. He is captured and his club is broken. Enkidu, the friend of Gilgamesh, usually plays a glorious part as helper in the contests with wild animals. It is surprising to find him embodying the power of darkness and the brooding clouds. But there is no mistake about the hero of light, his victorious attitude, energy of action, the flames issuing from his body, his divine horned mitre. His opponents are generally heroes of the same type but nude and without flaming wings. Their broken clubs express their defeat. The long pleated kilt of the solar heroes savours of the Kish style, and may betray the influence of Sippar, another northern city devoted to the Sun God, who was only the son of the Moon God and a minor deity at Ur. This curious seal is another index of changing times. U 9717.

- Kish hero between two wild animals, a goat with beard, tufts of hair at the knees, curved horns with nodosities and one antelope—or moufflon?—with shorter rugged horns, no beard, and smooth knees. A lion and a bearded bull. Two small motifs, a goat in a bush, and a beardless bull. U 9809.

- A bull attacked by two Kish heroes. The second strikes the bull from behind with a dagger. Instead of a flat cap he wears a turban. Enkidu and the lion. U 9693.

- The seal of Mu-lugal-gish(?). The Kish hero strikes from behind with an axe, or a crooked club, an oryx antelope which he has caught by the long straight horns, while a lion bites it in the neck. In a second group the same hero armed with a club has caught a deer in his arms. The figure of the deer and the linear writing prove the seal to be one of the older in the series. U 9661, CBS 16874.

- Two bearded bulls with triple belt attacked by two heroes. One has the Kish flat cap and short loincloth. The other, nude, except for a belt, and with head in profile, short beard and hair, is the southern hunter in a new style—a would-be Gilgamesh. Enkidu carries in both hands the lance with buckle and pommel. In the field a crooked club and an arrow. The contests with wild animals and the fights of solar heroes have points in common. U 8993, CBS 16875.

- Kish heroes armed with club and dagger, and bearded bulls. Tree of archaic type. Recumbent gazelles. U 7989, CBS 16864.q

- Kish heroes fighting with bearded and beardless bulls. Enkidu and the lion. In the field a curved club. U 9283.

- Kish hero, lion, beardless and bearded bulls. Enkidu and the lion. U 7617, CBS 16877.

- The Kish hero and Gilgamesh fighting with two bearded bulls. A new episode of the mythology of light. The Sun God rising above the line of a mountainous horizon. U 9321.

- The Kish hero and Gilgamesh, bearded bulls and lion. Enkidu and the deer, and a diminutive hunter treading on the animal’s hind leg. U 9740.

- Kish hero, Gilgamesh in profile, bearded bulls, Enkidu. U 9808.

- Kish hero, Gilgamesh, and bearded bulls. Antelope be-tween Enkidu and a lion. In the field, a snake and a scorpion prove the seal to be archaic. U 11112, CBS 16880.

- The seal of Lugal-tug son of Lugal-ab. Two groups of Gilgamesh and a lion. Between them three ears arising from reedlike masses, usually connected with Nidaba, goddess of agriculture. Mr. Woolley suggests reading instead of Lugal-ab, a proper name: son of the king of Erech: “One of the nameless kings of the second dynasty of Ur which flourished perhaps just at this time (the reign of Lugal-zaggisi, B.C. 2662-2638), and was crushed by Sargon of Akkad” (Antiquaries Journal, Jan., 1928, p. 25). U 8416, CBS 16870.

- Kish hero and the lion. Lion and water buffalo. U 9652, CBS 16857.

- Kish heroes and Gilgamesh treading on uplifted lions. Gilgamesh’s head is in profile and he wears a loincloth. A tree in the field. U 9298, CBS 17012

- Rock crystal seal of Urkhur ga-ab-di, servant of the goddess Innina. Two Gilgameshes. One carries a lion by neck and tail like a sheep. The second rides a water buffalo. A crouched antelope. “The hole down in the centre of this crystal seal has been filled with red and white paste in such a way as to form a chevron pattern which is visible through the walls of the seal. There were copper caps affixed to the two ends.” (C. L. Woolley, Antiquaries Journal, Jan., 1928, p. 25.) U 7953. Property of the British Museum.

- Bulls and lions. Gilgamesh in Kish style breaks the back of the lion. He is armed with a club, or is throwing a rope round its neck. U 10355.

- Seal of Aharrum, ” the last one” (or Amurrum). Gilgamesh and the buffalo. Enkidu and the lion. In the field a small seated dog, a crescent, a sun emblem: a cross with rays of light between.

- Two groups of Gilgamesh and the buffalo. The inscription is erased. In the field two small mythological figures. The goddess of agriculture Nidaba seated on a stack bristling with ears ofbarley, and the hero Etana raised to heaven on the pinions of an eagle (Cf. Museum Journal, March, 1928, p. 7). U 9679.

- Seal of Urgubba son of Lumakh. Gilgamesh and the buffalo. Enkidu and the lion. U 8666.

- Seal of A dSin-dim, the cupbearer. Hunters and water buffaloes. Their heads are in profile. They have long hair, short beards, and woolly kilts of the Kish style, but no cap. U 10307.

- Seal of Gimililisu, the priest of dGishrin(?). Gilgamesh and the buffalo. Enkidu and the lion. U 9567.

- Gilgamesh and the buffalo. Gilgamesh in profile and the lion. U 7641, CBS 16861.

- Gilgamesh and buffalo. Enkidu and lion. U 7656, CBS 16865.

- Idem. The buffalo is shown urinating. U 9551.

- Gilgamesh in profile. An adze in the field. U 9145.

- Gilgamesh and the buffalo. Enkidu, the lion, and a second hunter. Bearded heads in profile with a band tied about the hair. A lance with buckle in the field. U 11152.

- Hunter and bull. Enkidu and lion. Antelope, star, and crescent. U 7923.

- Hunter and bull. Enkidu—shown urinating—a lion and a bull. U 10302.

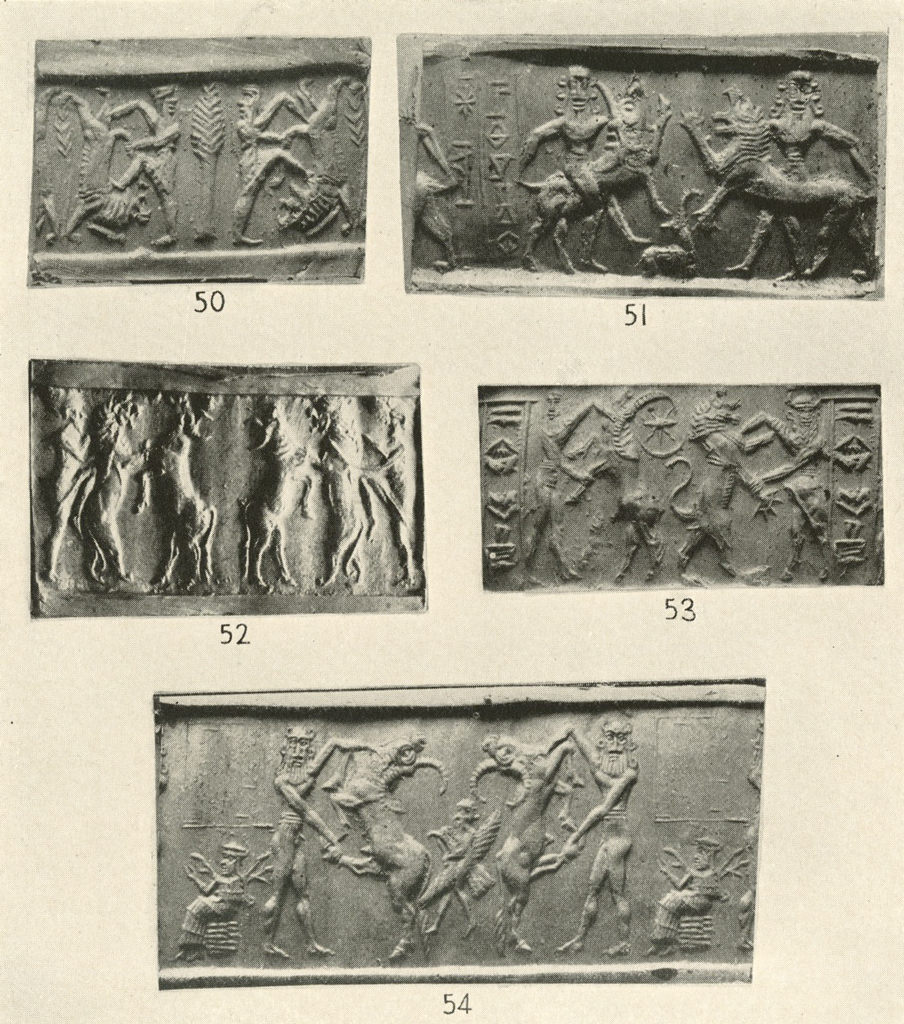

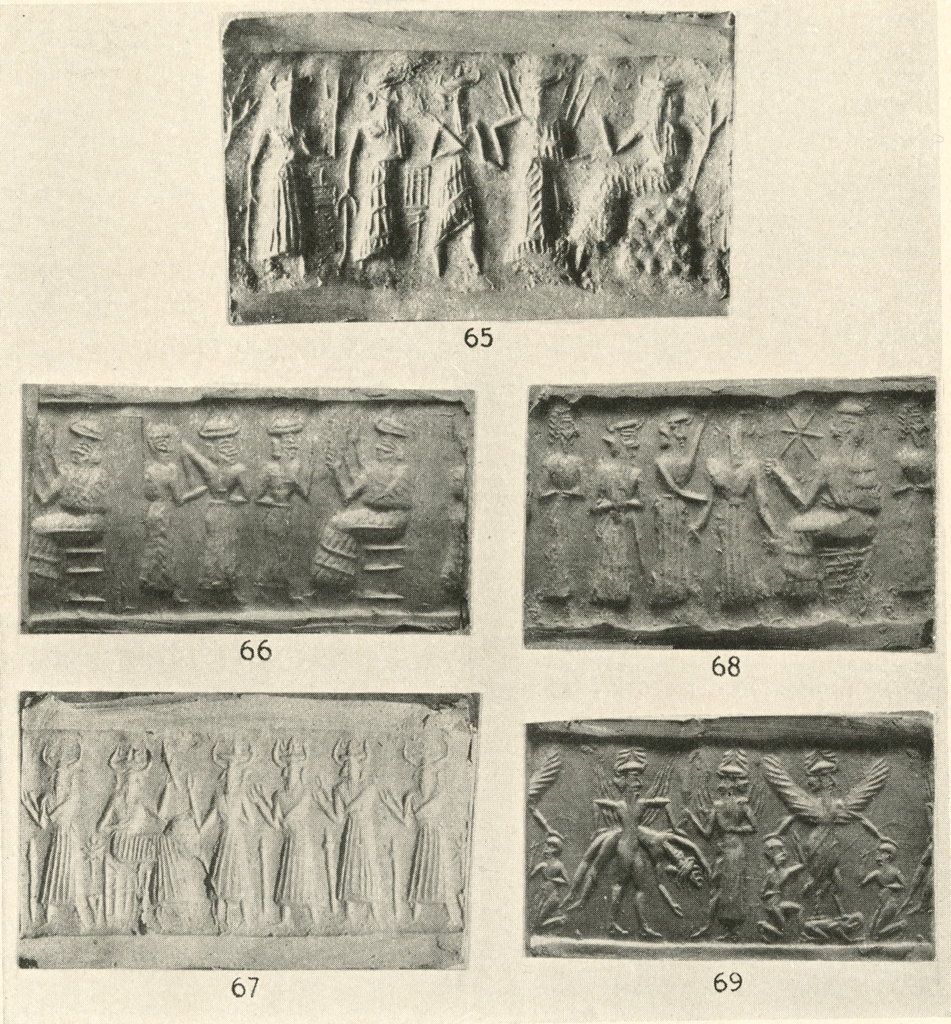

IV. The Myth of Light. The Hero Shamash

Shamash, the young hero of light, opening the gates of dawn, rising at morn over the Persian hills armed with his golden saw, the divine archer who pierces with his golden arrows the powers of darkness, the mists and stormy clouds brooding over the mountains, who breaks men’s backs or their clubs, pulls off their crowns or their beards and forces them to their knees, the triumphant warrior who passes at noon the tops of the stage towers, the great divider between day and night, the supreme judge from whom nothing is hidden, has always inspired Babylonian mythology. The magnificent language of the Psalmist rivals the art of the gem cutters.

The heavens declare the glory of God . . . In them has he set a tabernacle for the sun,

which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber,

and rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race.

His going forth is from the end of the heaven,

and his circuit unto the end of it :

And there is nothing hid from the heat thereof (Psalm XIX).

Museum Object Number: B17012

Image Numbers: 8925b, 9196, 8928, 9205, 9235

Museum Object Numbers: B16865

Image Numbers: 8926b, 9199, 9212, 8924, 9239

Image Numbers: 9207, 9208, 9239, 9243

Shamash was worshipped at Larsa in the south and at Sippar in the north, the supreme court of the land in the days of Hammurabi. The famous Shamash of Sippara from Hammurabi to Nabonidus, was enthroned, sitting in judgment or receiving offerings. The morning Shamash, the fighting hero, was probably the god of Larsa, unless Sippara worshiped him in Sumerian times under the same aspect. Two figures of the rising god with flaming wings on one remarkable seal, provide grounds for the supposition. Both are placed high, the one between mountains, the other on the stages of a ziggurat. One lifts up his golden saw, the other lets his club hang. One wears the pleated kilt of Kish, open in front, with one end tucked in the belt, the other a short Sumerian kilt of kaunakes closing behind. Their crowns are different. One wears a mitre with one pair of horns and a central piece adorned with three small pairs. The second has no central piece but three pairs rising in pyramid form. The ziggurat has four stages supporting a tower-like construction. The mountain climber stands on a roaring lion—emblem of Nergal, god of Hades, the underground kingdom of darkness—and steps on the shoulder of his vanquished enemy, who is kneeling and crying for mercy. The presence of so many seals of the Sun cult and the doubled figure of Shamash on one seal in the Ur cemetery prove the growing influence of the north after Sargon.

- Seal of Ezida the scribe. A solar deity introduces to the mountain god his fighting servants. All are bearded male figures and wear the same mitre with one pair of horns and a central piece. Their dresses differ. Shamash and the mountain god wear fringed shawls covering their left shoulders. Shamash has flaming wings, and a tree grows from the hilly seat of the mountain god. The servants wear only a kilt. The first, led by the hand, has a short kilt of kaunakes showing the knee and carries his curved club on his shoulder. The two attendants carry their clubs head down. Their kilts of woollen kaunakes or pleated linen fall to the ankles. A three-pronged fork in the field. U 11107.

- Shamash the divider with flaming wings and golden saw sits in judgment. A worshipper is led in and introduced. Dresses and mitres express the difference in rank of the god, the attendants, and the worshipper. U 9292.

- Shamash and his attendants. He sits club in hand. Other clubs and a golden arrow—his emblem—are planted in the field. All wear the long pleated kilt after the Kish style, and the peculiar mitre with a central piece and two small pairs of horns between a larger pair. U 9851.

- Shamash sitting in judgment, his gold saw—or club—in hand. The accused has been arrested and convicted. An attendant pulls off her(?) hair or crown. A verger precedes the worshipper, the just man in the case. Shamash is dressed in kaunakes, the others in pleated skirts. The starlike emblem of the sun is really a cross with undulating rays. U 9165.

- The triumph of solar heroes. The bird of darkness and stormy clouds oppresses humanity. He tramples on a prostrate man, and holds under his hands two nude, kneeling, imploring figures. He is the robber bird-man Zu. Shamash of the flaming wings and of the golden saw shines through the clouds. He wears the pleated kilt of Kish style. One of his nude athletic servants breaks the back of the hero of darkness. His two arms and flaming wings surge above their receding line. Only the vanquished enemy has the mitre with a central piece. U 9026, CBS 16876.

- The seal of Ur dNidaba. The triumph of solar heroes. The god with flaming wings pulls the beard of his enemy and forces him back on the mountains. He has caught his club before he could use it. A second pair are wrestling. U 9310, CBS 17009.

- Episodes of the triumph of solar heroes. The enemy loses his crown, is pushed back to the mountain, forced to his knees, and pulled by the beard. U 9060.

- The divine archer, helped by Ishtar the goddess of war, pulls the hair and beard of his enemy after piercing him with his arrows and forcing him back to his mountain. An attendant wears the curious mitre with a central piece, perhaps an old Sumerian model. The archer with the pleated Kish kilt, curved Asiatic bow, and tasselled quiver hanging from his shoulder is a northern Akkadian of Sargon’s time. So is Ishtar, full face, with a caduceus(?) in hand and clubs on her shoulders. Ishtar wears the kaunakes and her follower a fringed shawl. U 9694.

- Shamash of the flaming wings and the golden saw seated in his shrine. Two attendants fling the doors open. They wear pleated skirt and fringed shawl. U 9100, CBS 16879.

- Shamash standing in his shrine. He and the two attendants wear the pleated kilt. In the field the golden arrow, his emblem. U 8699.

- Worshippers at the shrine of Shamash rising over the top of mountains, with the usual saw and flaming wings. The bearer of a kid is the only one to wear a fringed shawl. The others wear the pleated kilt and the curious mitre with a central piece. The porter has his long hair hanging down his back. The libator holds the spouting vase. The main priest stands before the idol. U 8749.

- Beautiful seal of the three gods: the two solar deities described above, and Enki, the god of Eridu. Enki sits in his shrine surrounded by water. He is a god of vegetation and commands the springs arising from the deep abyss. Streams and green branches issue from his shoulders. The little curtain on the top of the shrine may represent the waters from above. A kneeling Gilgamesh at the back winds his arm round the lance with a buckle, the tarkullu, solidly planted in the ground and marking the entrance. U 9750.

V. Myths of Vegetation

Museum Object Numbers: B16876

Image Numbers: 9215, 8640, 8641, 9237, 9244

Grain and dates are the wealth of Babylonia. The immortal words of Herodotus are the best commentary on this series of seals.

“Rains are not frequent in Babylonia. The water from the river nourishes the root of the grain and causes crops to grow, not like the Nile by spreading over the lands, but by strength of arm and by means of machines, for Babylonia like Egypt is all intersected by canals, the largest of which carry boats. Of all the countries we know, this is undoubtedly the best and most fertile in the grain of Ceres. No one tries to grow fruit trees there. The fig tree, the vine, the olive tree are not seen; but instead the soil is so good for all kinds of grain, that it always brings two hundred times as much as is sown, and in exceptional years, three hundred times as much as it has received. Wheat and barley leaves are about four fingers wide, and though I am not ignorant of the height to which stalks of millet and sesame grow, I will not mention it, being persuaded that those who have not been in Babylonia could not believe what I have reported about the grain of this country. . . . The plain is covered with palm trees. Most of them bear fruit; one portion is eaten, from the other they make wine and date-sugar.”

Museum Object Numbers: B17009

Image Number: 8925b, 9196, 9211, 9212, 9235, 9236

Gathering the fruit of the palm tree was mistaken, years ago, for a scene of paradise, but dates certainly were food for the gods. Bunches of ripe dates placed in a vase with green boughs were offered to them. The scene is common from the days of Shubad to the end of the third dynasty of Ur. Short Sumerian figures, in kilts of kaunakes, sit at a feast and enjoy a cup of palm wine or honey, when the crescent announces the beginning of the harvest month. Later a ritual procession of priestesses in long dresses, wearing the horned mitre, advance toward a seated figure, which takes its meaning from the palm tree in the field. The crescent shines in the sky. Or a priest performs a libation in front of the seated goddess. The altar is a small table with a ledge. The crescent, a tree, and a star denote harvest time and offering. In former days the priest, entirely nude, poured the libation on palms and bunches of dates placed in a tall vase. On other archaic seals, offerings in the form of a bundle of sticks(?) are placed behind the vase. Ritual meaning and all formality seem absent from a charming group of a mother and child to whom servants bring dates and water.

Museum Object Numbers: B16924

Image Numbers: 8640, 9237, 9238

Nidaba the goddess of wheat and Ashnan the god of barley were not represented as king and queen by the gem cutters long before the time of Sargon. They are picturesque figures dressed in kaunakes or in pleated linen, but covered with ears of corn, and seated on stacks of grain. The first green ears were solemnly presented in the temple. We see them in the hands of the high priestess, and a ceremonial plough in the hands of a priest, on the beautiful seal of Ursi, the distributor, or chief of cultivation; they are the servants of Enmenanna the high priest of Ur. The procession is led by a verger—probably Ursi—towards the seated god, dressed in the best style of the time of Gudea. His emblems are a star, a flag on a tripod, and a gazelle. He must be a solar deity. The rays of the sun are more important to the corn fields than the crescent of the moon.

- Nidaba receives three worshippers, one of whom represents Ashnan, bristling with ears of corn like Nidaba herself. All have both hands extended, the pleated skirt, and the horned mitre with a central piece. A fourth attendant has a different attitude and dress. He carries in his hand two long stalks, and his skirt is of woollen kaunakes. An arrow is planted in the field as an emblem of solar deities. U 10397.

- Three worshippers, one of whom represents Ashnan the god of barley, approach a bearded god armed with a club. A second club is planted in the field. Like arrows and stars they are emblems of solar deities. The crescent marks the beginning of the month of harvest. U 9158.

- The seal of Ursi, the distributor, servant of Enmenanna, described above and in a foregoing article, page 236. U 9844.

- The harvesting of dates on an archaic seal of the time of Shubad. In the lower register nude figures are cutting bunches of dates from the trees. Above is represented the ritual offering and the feast of the first fruits. Palms and bunches of dates are placed in the large vase between the seated priestess and her servants. All wear the old-fashioned Sumerian skirt. The priestess, distinguished by her heavy roll of hair, holds a cup full of palm wine. The crescent marks the beginning of the new month and the time of the feast. Behind the vase is shown the curious pile of sticks found in ancient ritual scenes. U 10323.

- The month of the date harvest. A procession of three approaches the goddess seated on a large elegant stool. One is the worshipper; he wears a simple fringed shawl. Two are assistants, probably priestesses, in long pleated robes, long hair and horned mitre. A well cut palm tree with rugged trunk, having boughs and fruit, gives the scene its full meaning. U 9749.

- Libation ritual at the beginning of a new month, probably a feast of the harvest of fruit. The ledge altar is placed between the seated goddess and the priest, who is pouring a liquid from a jug into a cup on the lower ledge. An assistant goddess stands at the back of the scene. She wears a pleated skirt, but has the same long hair and horned mitre as the chief goddess, who is seated below the crescent. The scene in the lower register is more human. The day star is on high. Altar and mitres have disappeared. The long tresses are tied in a roll on the neck. The green tree suggests an orchard. The three female servants approach the seated priestess with greetings. U 7956, CBS 16856.

- Mother and child surrounded by three servants bringing offerings: one a bunch of dates, another a small jug hanging on a string. All are female figures, with the roll of hair tied on the neck. Nothing could be more human than this charming intimate scene. This carnelian seal mounted with two gold caps, belongs to a rich burial of the Sargonid period, 2700 B. c. With it were found a translucent calcite lamp decorated with a bearded bull in relief, three strings of beads, a gold diadem to be fastened with gold wireacross the forehead, a golden ribbon twisted round two tresses of hair above the frontlet, two gold bracelets, two gold earrings, three copper vases. U 10757, CBS 16924.

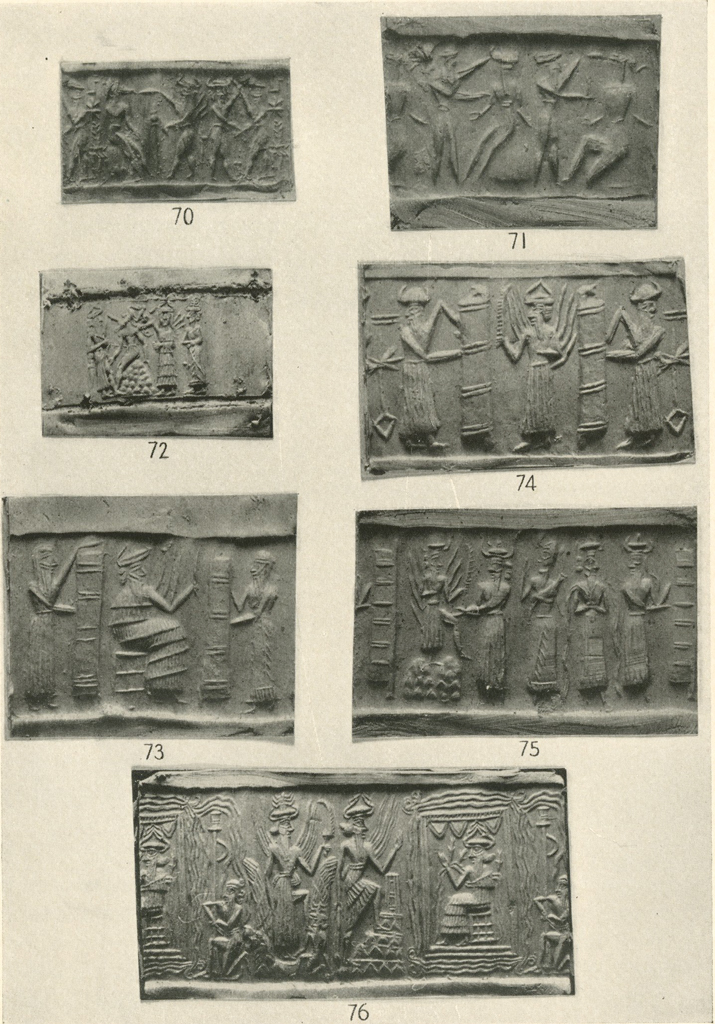

VI. Wild and Domestic Animals

Museum Object Numbers: B16294 / B16288

Image Numbers: 8928a, 9202, 9207, 9208, 9211, 9218, 9235, 9241

The old hunter took delight in the figures of wild animals: bulls, deer, ibexes, antelopes passing in long lines over the hills, amidst flowers and bushes. He never tired of having them engraved on his seals: a vivid picture of natural grace in proper surroundings. A more formal style placed symmetrically opposed figures on each side of a mountain, or arranged them rampant against the trunk of an Elamite pine tree. Spread-eagles and nets are the emblems of a successful quest, stopping the game and catching it alive. Antelopes and ibexes are seized in the talons of the powerful eagle, and bend before him on their knees. The wild bull is a captive in the byre, and the gate closes on him like the wings of an eagle. The cowherd pulls a rope to keep it tight. A protecting goddess of herds and pasture helps him. The hunter is giving place to the farmer.

The shepherd, whip in hand, leads his sheep and goats out of the pen. He is often followed by his dog. Strainers, pots, and jars for storing cream and milk, twelve round cheeses arranged on a wattle complete the picture of a well-kept dairy.

Museum Object Numbers: B16300

Image Numbers: 8928a, 9202, 9209, 9210, 9233, 9528, 9814, 9815

Geese, ducks and swans, or long lines of fishes are the emblems of the marshes and rivers so important in the south. Bau, the Mother Goose popular at Ur, presided over them. She had her statue in the shrine of the Moon Goddess. The fishermen liked her figure on their seals. At Diqdiqqeh, on the edge of the Ur canal, have been found two black diorite seals of Lugalushumgal and of his wife. He was interested in boat equipment or construction, and so was his father Urshul before him about the time of king Bur-Sin. Lugalushumgal married Nin-dingir, the priestess. On his seal a priestess leads him by the hand to the throne of the Moon Goddess. But swans adorn the seal of his wife who was probably a worshipper of Bau. With her we close the cycle of graceful myths derived from the worship of the natural forces of heaven, land and water.

- Lines of gazelles with the long horns of the oryx. The two registers in inverse direction belong to a very ancient technic. Many seals of the same type were found in Kish. U 8388.

- Lines of deer and ibexes in a landscape of mountains, plants, and flowers. U 9751.

- Idem. Lapis lazuli seal. U 6133, CBS 16294.

- Ibexes rampant arranged against a pine tree. Second tree in the field. U 8584.

- Bulls passant in a mountain pasture. A bird is perching on high branches. A crescent. U 8169.

- Bulls rampant among hills and pine trees. U 11123(?).

- Spread-eagle over two gazelles. A net. U 7118, CBS 16288.

- Idem. A star and a crescent. U 9051.

- Idem. A crescent. U 9618.

- Recumbent bull under a winged gate. A seated goddess and an assistant hold the rope which keeps the door closed. U 7909.

- Curious scaraboid seal of glazed fritte. Two bull-men bring two crescent emblems on a pole to the enthroned Moon God. Each wears a triangular horned mitre and long hair tied in a roll. A bull passant below the throne is the emblem of the god. All the figures are deeply incised and schematic. The convex back of the seal is cut by a middle line and adorned with rings like the wings of a ladybird. It is hard to date this seal which was found in a grave outside of the city. U 7027, CBS 16301.

- Dairy scene, like the famous Al’Ubaid relief and other examples of the same type (Museum Journal, Sept., 1924, pp. 167-168). The same goats, goatherd, jars, pails, buckets, cheeses on a wattle, and dairymen. A bird is perching on the gate of the pen. U 8385.

- Ducks and fishes, the products of the marshes. U 8675.

- Swans on the river. A female worshipper is led by the priestess to the throne of the goddess. The evening star shines on high. U 7664.

- Idem. U 6065, CBS 16300.

- Idem. Seal of Nin-dingir, the priestess, wife of Lugalushumgal. U 1268, CBS 15593.

- A worshipper is led by the priestess to the throne of the goddess. He wears a fringed shawl, the priestess a pleated robe, the goddess a woollen kaunakes in good Third Dynasty style. Crescent and star emblems. Seal of Lugalushumgal, son of Urshul, by profession a ” cutter,” tug-du-a. The name of Urshul, in connection with the profession, is read on a tablet dated in the third year of King Bur-Sin of Ur. The profession seems to concern boat building and is mentioned along with carpenters and caulkers, nagar, adkit, tugdua, sa, kugdim on pay list of people repairing the boats of the goddess Nina and of the gods Nindar and Dumuzi. U 1257, CBS 15592.

VII. Ritual Scenes

Museum Object Numbers: B15276 / B16948 / B17024 / B17598

Image Numbers: 9207, 9208, 9218, 8640, 9233, 9238, 9241, 9817

The banquet is the supreme manifestation of human joy. No festival without a banquet. None would approach the gods, courting their favour and bringing a request, without first rejoicing their hearts by the best offerings of food and drink. From the human banquet to the ritual sacrifice there is only a difference in mode. Both are essential to a religion of life, which is the gift of the gods and the desire of humankind.

“In those days, when king Ahasuerus sat on the throne of his kingdom, which was in Shushan the palace, in the third year of his reign, he made a feast unto all his princes and his servants: the power of Persia and Media, the nobles and princes of the provinces being before him . . . and they gave them drink in vessels of gold . . . and royal wine in abundance according to the state of the king.” (Esther.)

The golden tubes and cups of the symposium, the sideboards and the offering tables loaded with bread and meat of the time of Shubad give way in the days of Sargon to formal processions of worshippers bringing a lamb, a kid, a cup of wine to the seated deity. A ledge altar and a vase with green boughs replace the old sideboard. The harps and cymbals are not heard or represented. The nude libator priest learns to dress properly. The attendants, servants of the god, or priests playing the part and wearing the horned crown, lead in the worshipper by the hand to introduce him, and adore the god in front of the idol in the inner shrine. Later, altars, tables, vases disappear. One emblem in the field is enough to give colour to the scene and personality to the god. The imaginative myths die out. At the time of the third Ur dynasty, the introductory scene has taken on a dull monotony. Influences due to new invasions produce scarcely more than a new dress, a new emblem of a freshly imported god. The glory that was Sumer is gone forever.

Museum Object Numbers: B16287 / B16298 / B15248 / B16306

Image Numbers: 9206, 9811, 9812, 9813, 9816, 9817

- Symposium. A jar with two tubes between the two drinkers. A servant and a tree. U 9587, CBS 16948.

- Symposium reduced to two seated figures, two tubes and a pot. Very small lapis seal. U ______ , CBS 15276.

- Symposium. Two tubes in a jar between the two drinkers under a crescent. One servant. Dresses are long, plain or pleated, and posterior to the time of Shubad. U 9117.

- A short tripod table loaded with food, cakes, and a leg of lamb, is placed between the seated goddess and the two worshippers. Crescent. U 11148, CBS 17598.

- Banquet. Two seated figures and two servants. The bearded god under the star holds a cup. His beardless partner under the crescent pours a libation on the ground. Both wear kaunakes dresses, their hair tied in a roll, and no mitre. So does the servant in a fringed shawl. A second servant or worshipper wears the flat cap, hair, and beard after the fashion of Kish. U 9721, CBS 17024.

- Symposium. A seated man holds a cup. A procession of four servants, one of whom carries a jar. All wear the same fringed shawl and roll of hair on the neck. U 8793.

- Seated god, servant with cup and jar, and worshipper. A small table between two posts with buckles under a star figures the shrine. A crescent. U 9858.

- Offerings to a seated bearded god, with long hair falling on his back. The servants bring one hourglass-shaped vase, a cup and a basket, a young kid, and a bunch of dates. The second has his hair curiously tied in a roll. U 9282.

- Offerings to a seated bearded god. The priest wearing the horned mitre introduces the worshipper who carries a kid, and his wife with a pot of wine or cream(?). The small tree suggests a god of vegetation. U 8093.

- Introduction to and worshipping of a seated god. The seal of Nin-rin, the diviner (iskim) of the god Utu-sib. U 9681.

- Curious scene of a libation to the crescent standard of the Moon God, displayed on the body of a Gilgamesh engraved all round the seal. Between Gilgamesh’s legs is a squatting monkey, and between his raised arms a spread-eagle. A libator holds a spouting vase over an hourglass-shaped altar. He stands on a brick pavement in front of a crescent on a pole. Gilgamesh with the spouting vase stands on the other side of the pole followed by a worshipper with clasped hands. A second crescent on a pole is planted between the libator and a standing goddess. A third crescent on a pole is supported by two crossed bulls. U 6002, CBS 16287.

- Worshipper introduced by an assistant to the high priestess. The assistant holds a crescent on a pole. The priestess—in the part of the Moon Goddess(?)—holds a tumbler. The seal is inscribed to Shamash and to his wife Aa. In the field a small servant holds abig club; two nude fighters attack a dragon. This is an echo of the solar myth. The ampulla and libra in the field date the seal at about B.C. 2200. U 6698, CBS 16298.

- Presentation to a seated god in good style of the third Ur dynasty. Inscribed to Ur-Shubula, son of Imera, servant of Zabarku. U 7625.

- Libation to a western god, Dagan or Imera, carrying scepter, ring, and curved club, and dressed in Akkadian style. The libator follows the Gudea fashion of the intercessory goddess or priestess, the old Sumerian mode. Seal of Pesh-Dagan, son of Lumur-Imera. U 10407.

- A worshipper brings a kid to Shamash. The rising sun is armed with a saw, has lost his flaming wings, and his foot rests on a recumbent bearded bull. Two servants follow a Martu god of Amorite style, with short dress and turban, and with club in hand, There are small figures in the field behind Martu: a Janus with two heads, an Amorite servant with libation cone and pail. U 6255. CBS 16306.

- Shamash and Martu. Attitude and weapons are traditional but poorly cut. Gilgamesh holds a lance with buckle. In the field are the crescent and the seven stars of the seven spirits, perhaps the great bear constellation. Seal of Gummu-Sin, servant of the god Idpasag (Ishum?) and the goddess Ninkhursag. U 7524.

- War scene. Assyrian charioteer and archers. The bowman in the chariot shoots at his enemy, while the driver holds the reins tightly to control the galloping horse. Crescent and star. U 775, CBS 15248.

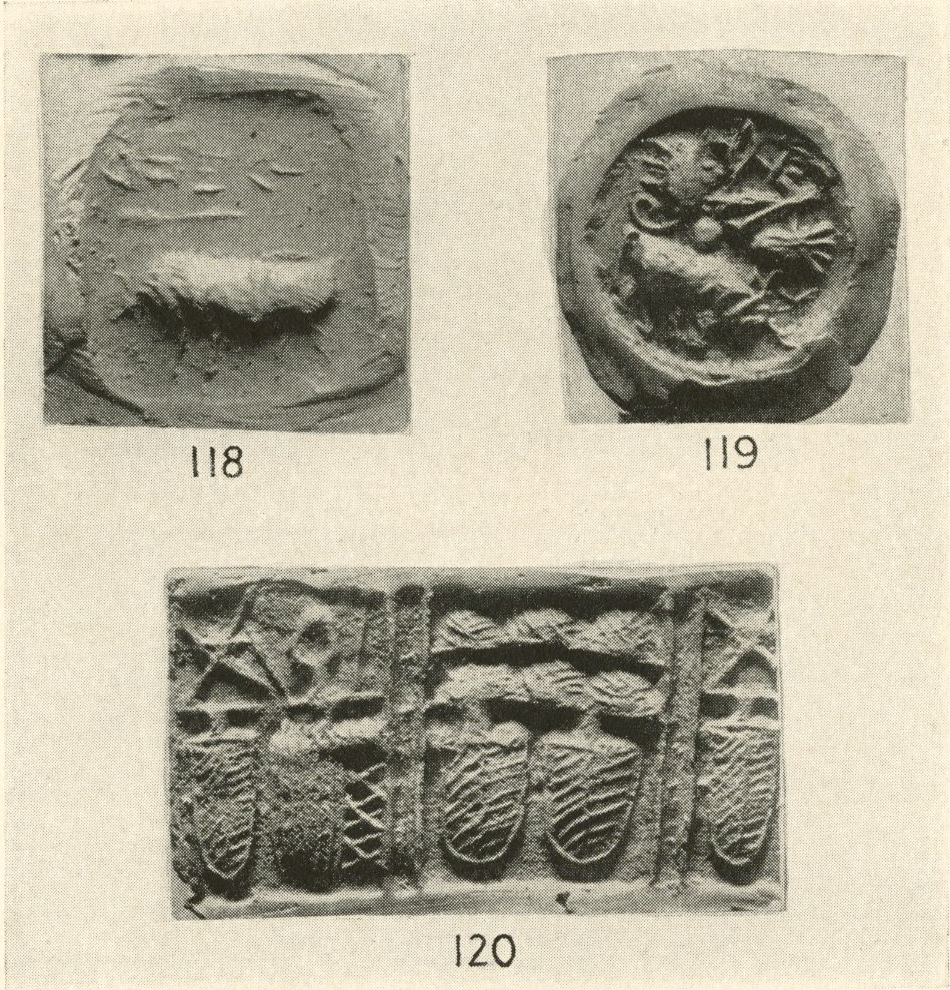

VIII. Foreign Seals

Image Numbers: 8925a, 9195, 8928b, 9204

A few seals from Ur betray a foreign influence. Their interest extends outside of the old Sumerian land and connects it with India.

- A bull passant with lowered head below an indistinct cuneiform inscription reading perhaps Ka-ku-shi(?). “It is a stamp seal, roughly rectangular, of grey steatite. The shape of the seal, the subject and the style are all those of the seals from Mohenjo-daso in Sind, but in the place of the proto-Indian script we have here cuneiform of a type which would agree with a date of about 3000 B. C. The seal was found on the surface of the soil, some distance to the east of Ur, a little beyond the cemetery called Diq-diqqeh. . . . This seal gives the first evidence for dating of the similar Indian material.” (C. L. Woolley, Antiquaries Journal, Jan., 1928, p. 26.) U 7623.

- Bull passant with lowered head, below a group of what are perhaps the pictorial signs of a primitive writing: a scorpion, a fish, a pelican(?), a round point. Round stamp of grey steatite found in the Ur predynastic cemetery. U 8685.

- Archaic human figure holding the horns of a bull. The head of the hunter is of the bird-like type reduced to one enormous round eye. The arms are filiform. The bull’s head is a schematic triangle. The bodies of the hunter and of the animal are lost in rectangular or scutcheon-like forms filled with straight and crossed lines. It is impossible to decide whether they represent the skirt of the man, a net, the body or hairy skin of the bull, or large vases. White shell seal found in the predynastic cemetery. U 8575.

The seals which form this small but choice collection from Ur will do honour to the old gem cutters. They can claim age, beauty, and historical interest. Parva domus sed apta.