A prominent feature of the exhibition of Polynesian artifacts in the General Ethnology Section of the Museum is a number of beautifully carved paddles, so called, from the Austral Islands. This class of objects, whose use was probably ceremonial and whose ornamentation had a religious or quasi-religious significance, has formed an important part of the material which has served to illustrate the discussion of the evolution of ornament among primitive peoples. Among the most important contributions to this discussion are the treatise of Sir C. H. Read, “On the Origin and Sacred Character of Certain Ornaments of the South-Eastern Pacific” [Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 21, 1891-1892], and that of H. Stolpe, “Phenomena of Development in the Ornament of Primitive Peoples” [Mitthei-lungen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien, Vol. 22 (N. S. 12)]. The similarities in the decoration of objects from different islands or groups of islands in the part of Polynesia—the Southeast —with which both writers deal, the fact that religious traditions and usages identical in many respects prevailed throughout the region and that communication was maintained among all the groups from the Herveys to the Society and Marquesas Islands, justify the assumption that the whole region may be regarded as a single ethnological province.

Museum Object Number: 29-58-10

Image Number: 15

Some of these facts are apparent from the earliest accounts. Captain Cook, sailing south from Tahiti in August, 1769, took with him a Tahitian native, Tupia or Tupaia by name, who, on a new island being sighted on the 13th of the month, told him that it was known to the Tahitians as Oheteroa. This was, in fact, the first of the Austral Islands—so called later by Malte Brim—to be sighted by a European sailor. Though Tupaia was mistaken as to the name of the island in this particular instance—it was, in reality, the island of Rurutu—he was able to indicate with considerable accuracy for placing on a chart drawn from information which he gave to the explorers the names and position of a large number of islands from the Marquesas in the northeast to the Hervey or Cook Islands southwest of his native group, and even beyond in the latter general direction. Rurutu he placed correctly at another time on the chart under its proper name and in company with two others of the group now usually known as the Austral Islands or the Tubuai group, from the island of Tubuai, discovered by Cook in 1777. The inhabitants of the various archipelagoes in this part of Polynesia must then have been in fairly frequent communication with one another. [Cf. The United States Exploring Expedition: Ethnography and Philology, p. 143, Horatio Hale]. Hale [op. cit. pp. 141143], following Ellis [Polynesian Researches (ed. 1853), iii, 380-381], is of opinion, based upon a statement in the Introduction to The Voyage of the Duff, quoted by Ellis [loc. cit.], and upon linguistic evidence, that the Austral Islands were settled from the Hervey and Society Islands only so lately as within the last two or three centuries (reckoning back from 1846) and Tubuai in particular not more than a hundred years before its discovery. However this may be, abundant evidence of various kinds is forthcoming to establish the fact that these three groups of islands in particular were closely linked culturally. The tiputa, a poncho-like garment of bark cloth, which Cook found the Tahitians wearing, he reports also from Rurutu [Cook I (Hawkesworth’s edition), ii, 275]. This was a specialization in wearing apparel not likely to have been of independent invention in neighboring areas ; its use in Samoa is to be credited to the missionaries who introduced it from the Tahitian or Society group in the early nineteenth century. The Tahitian variety of Polynesian speech was readily understood in the Austral Islands. Raiatea, one of the Society Islands, was the acknowledged center of religious authority in a radius of hundreds of miles of ocean, [Bastian, Inselgruppen in Oceanien, p. 21; Tyerman and Bennet, Journal of Voyages and Travels, i, pp. 529, 530, 555; ii, 14]. There was a tradition in Rarotonga, of the Hervey or Cook group, that that island had been removed by the gods from its former situation near Raiatea to its present position. Thus, in the Missionary Enterprises of John Williams, “another [Rarotongan] demanded [of a Raiatean member of Williams’s crew], ‘Why did you Raiateans kill those men, whose death induced the gods to remove our island to its present situation?’ “In a footnote to this the author remarks: “This evidently shows that the Rarotongans have the same traditions as the Raiateans, and, by the variety of information they possessed relative to the Society Islands generally, but more especially to Raiatea, that being the grand emporium of idolatry, it is certain that at some former time more frequent communication must have existed between the islanders” [op. cit., p. 103]. It was by trusting to the native method of employing landmarks “by which they steer until the stars become visible”, and steering accordingly, that Williams, sailing from Atiu, discovered the distant island of Rarotonga in the same group (the Herveys), of which he had heard before from the natives and endeavored unsuccessfully to reach.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-17

Image Number: 11

The objects which Stolpe uses to illustrate his demonstration of the derivation of the ornament characteristic of his “Rarotonga-Tubuai-Tahiti province” (of ornament) from representations of the human form are the adze handles of Mangaia in the Hervey Islands and the “paddle-form implements” of the Tubuai or Austral Islands. On the adze handles only the final result of what he shows to be the degeneration of representations of the human figure into recti- and curvilinear ornament appears. The paddles show this final result in an identical form, but also on the same examples the human figures, somewhat stylized, which are the starting point in the process of degeneration. The objects from which Read draws his illustrations are more varied in character and diverse in their places of origin (within the “province” referred to) than those in the contemporary but independent study of Stolpe. It is important to note that the theoretical demonstration of the origin and development of the style of decoration shown on these objects has confirmation from reality in the account of the signification of the carving on the adze handles of the Hervey Islanders given by the missionary W. Wyatt Gill from native sources. According to this account this carving, consisting, in the final stage of its development, of bands of lozenges bisected and separated by straight lines, was said by the natives to represent squatting figures of men—tiki tiki tangata [Gill, Jottings from the Pacific, p. 223]. On the occasion of the reading of Sir C. H. Read’s paper before the British Anthropological Institute, the President said that Mr. Gill had made a remark of similar bearing to him in conversation.

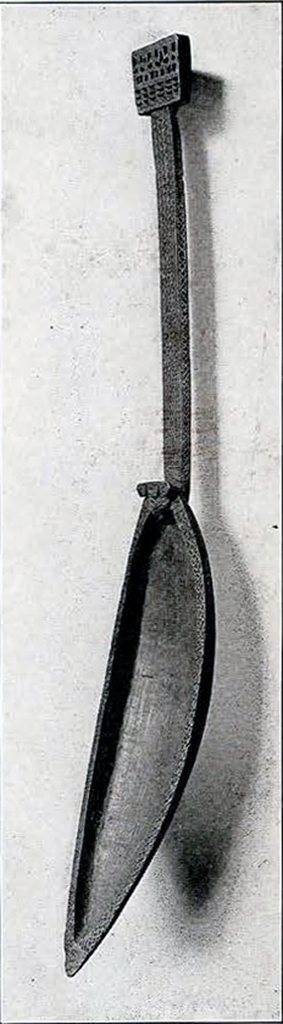

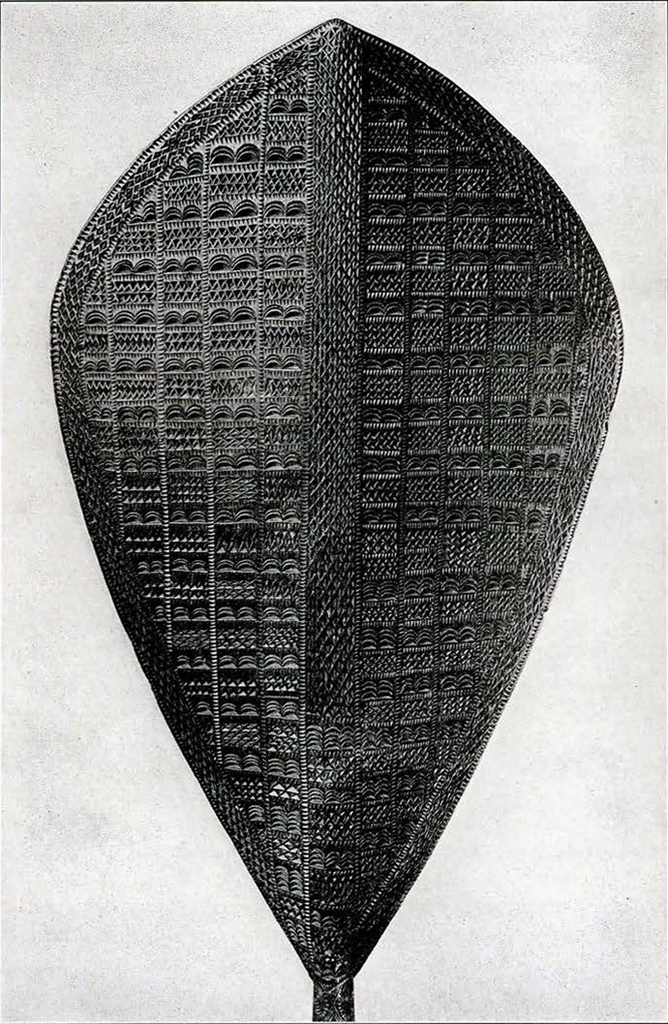

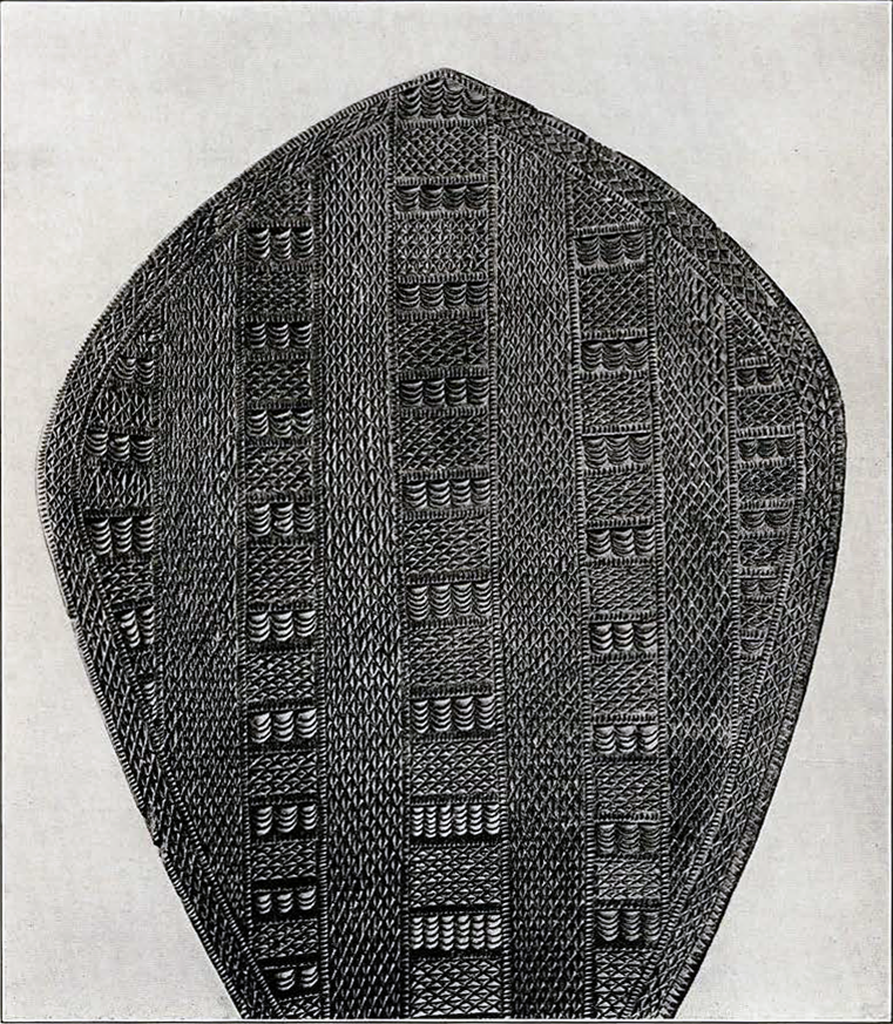

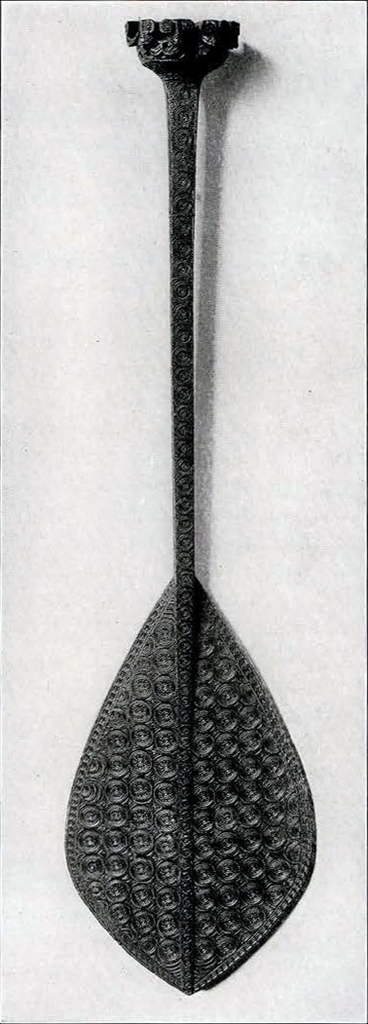

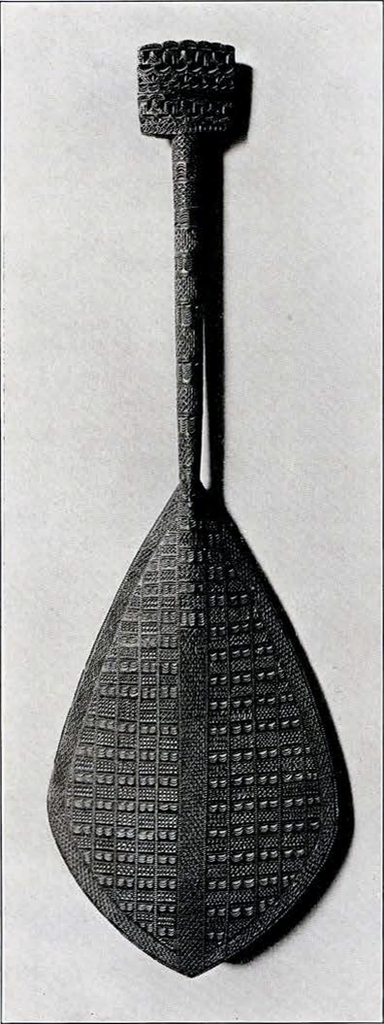

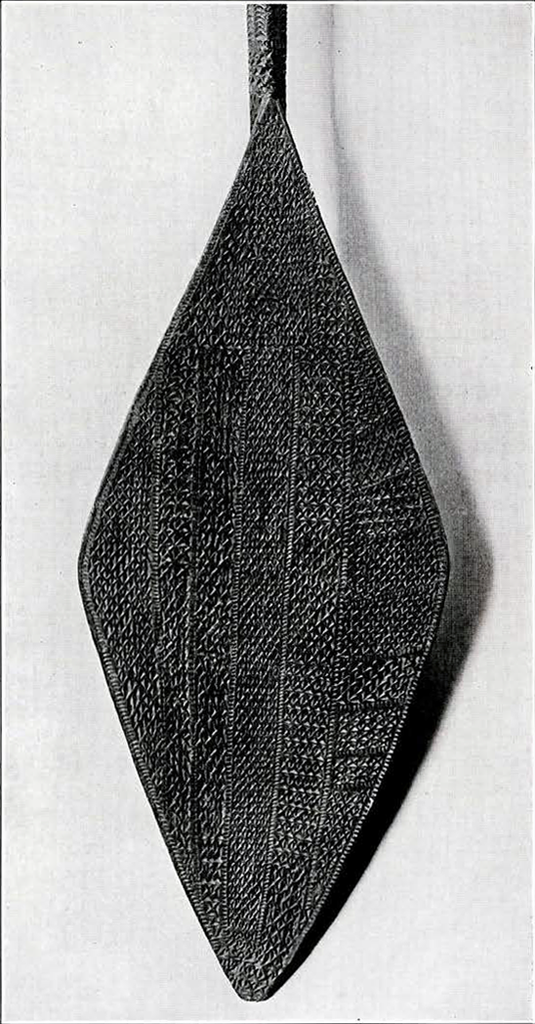

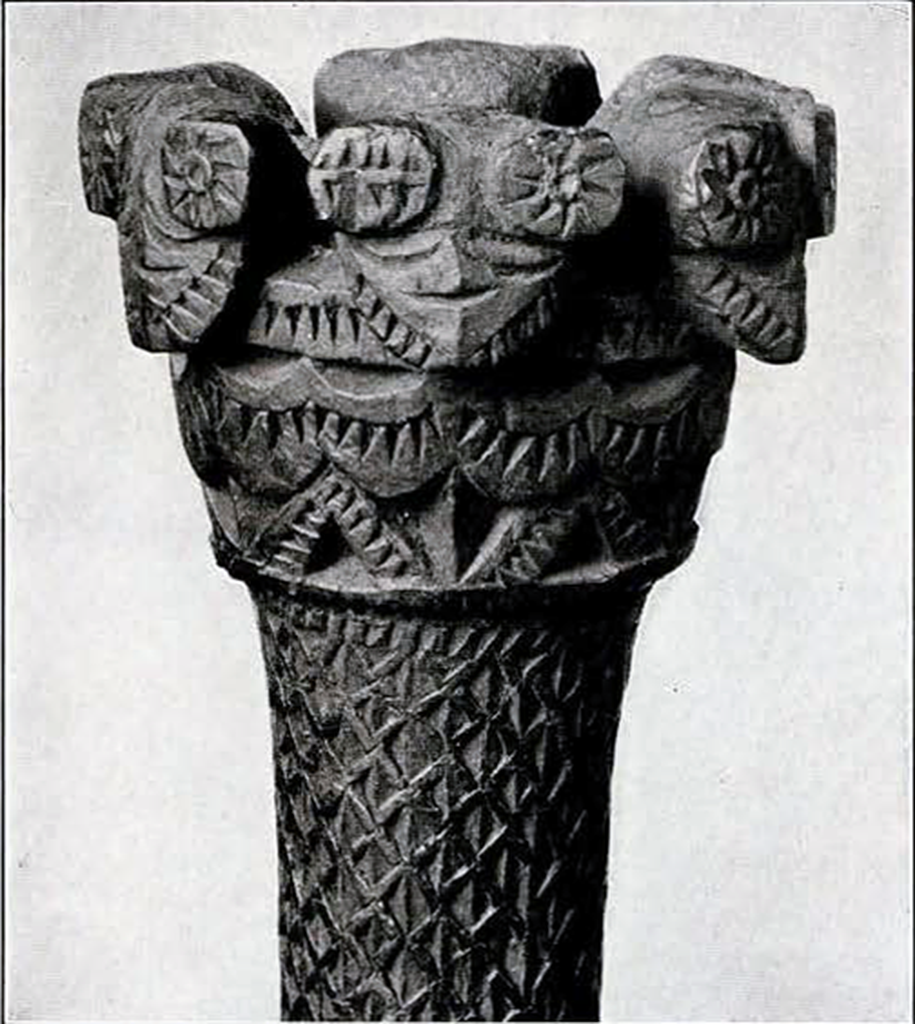

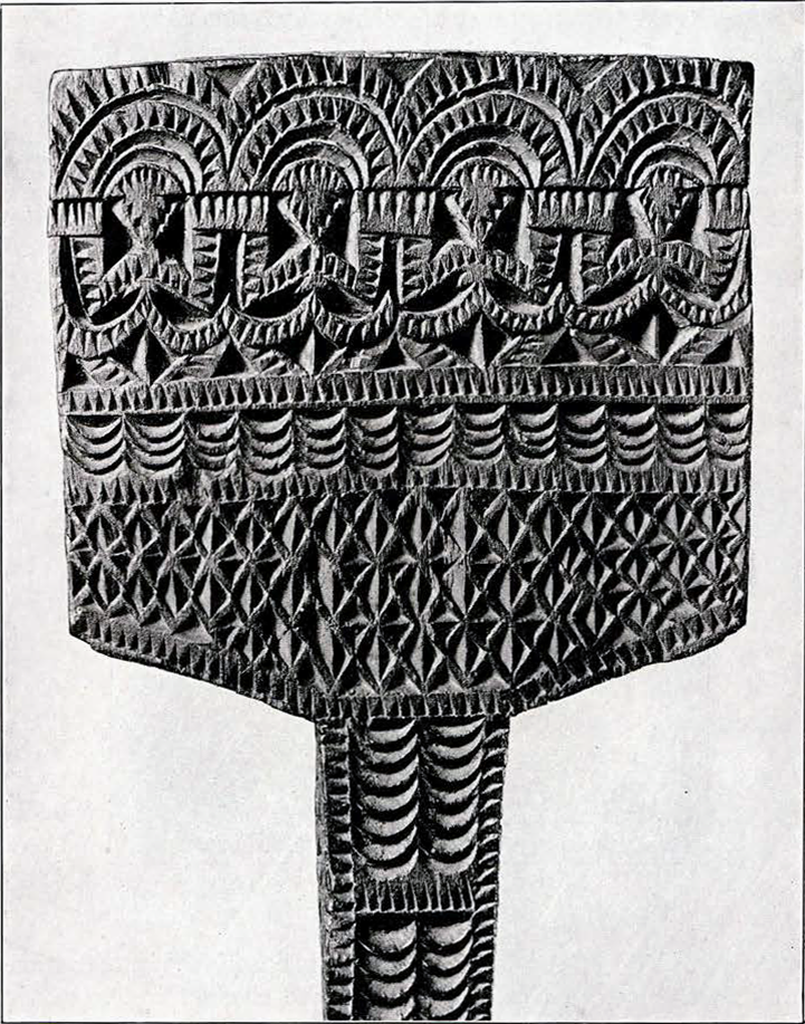

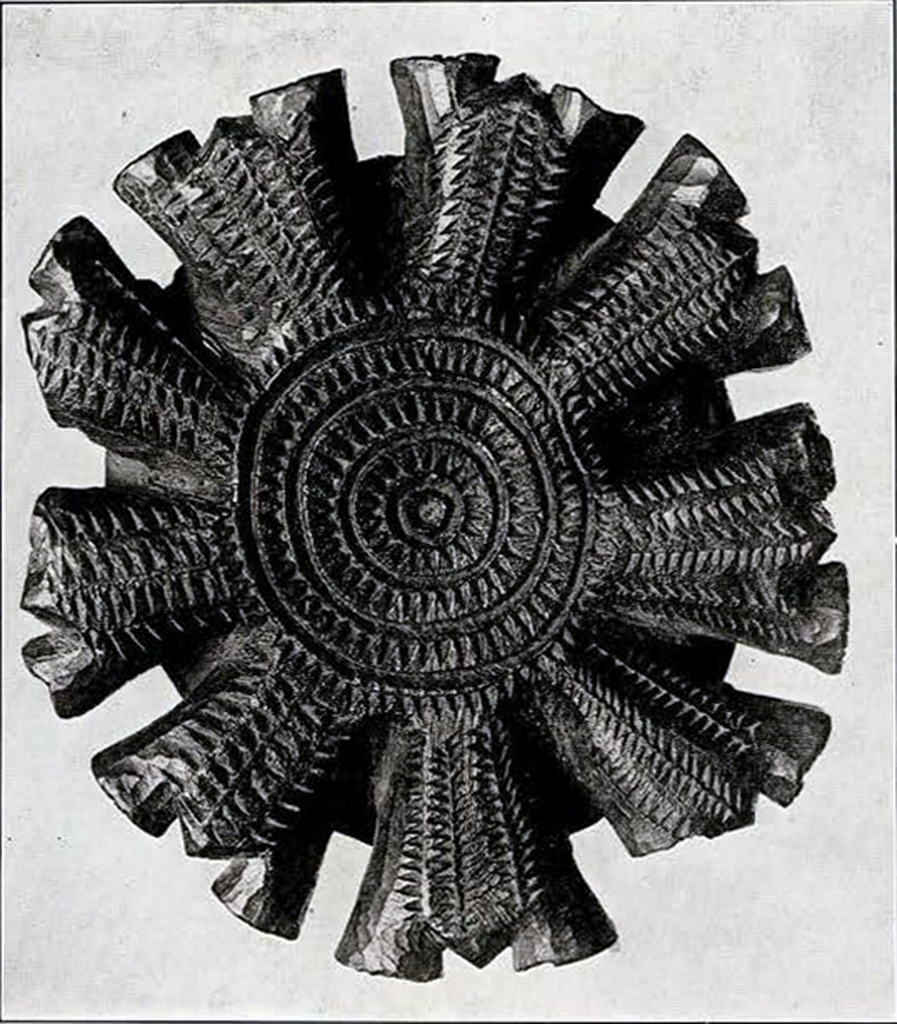

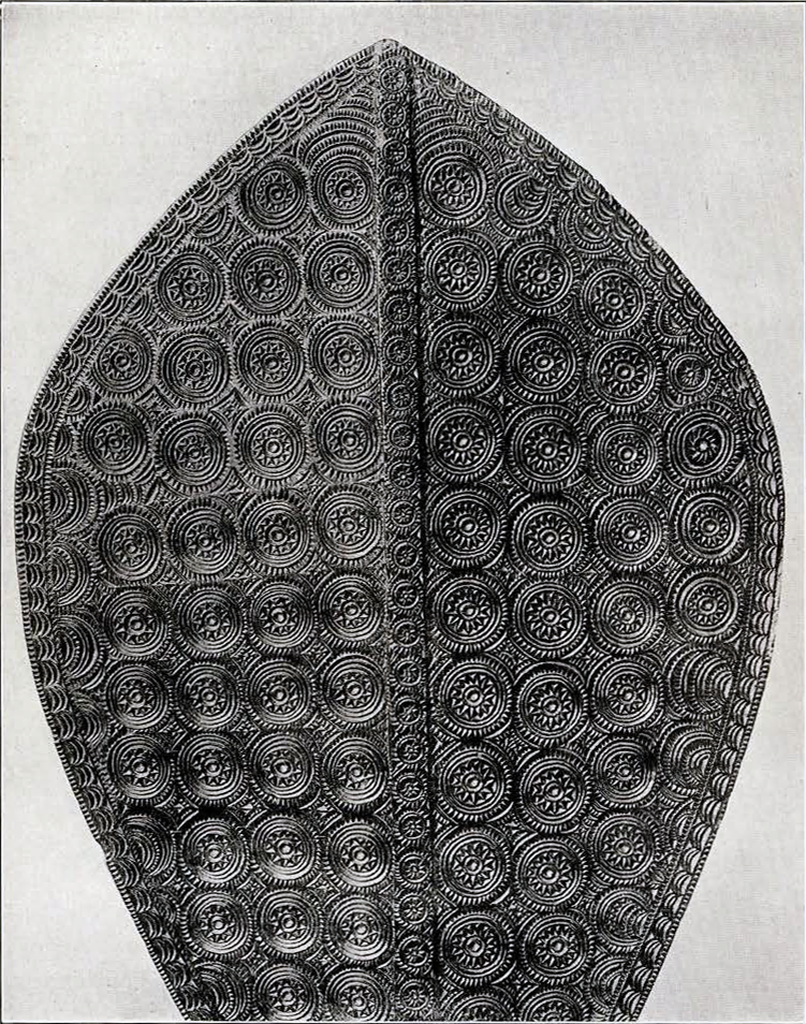

The form of the Austral Islands “paddles” and their characteristic decoration are illustrated here from examples in the University Museum. The blades vary in shape from rhomboidal, as in Fig. 57, to the commoner broad oval with the widest part nearer to the extremity (Figs. 55 and 56). The shaft of the handle is rounded or rectangular in cross section; the butt is a rectangle or trapezoid (Fig. 56) or else roughly conical in shape. On the butt the typical ornament is of squatting human figures with arms conjoined. When the butt is of the conical form these figures are in relief; otherwise they are in intaglio. Certain differences in the posture of the figures correspond generally to the difference in the form of the butts. On the conical butts the arms form a simple link between the figures grouped round the cone; there is no segmentation to indicate the joining of hands (Figs. 58, 59, 60). On the flat butts the arms are bent, the upper arm descending diagonally towards the crescent shaped thighs, while the horns of the crescents, representing knees, point upwards between the vertically placed forearms which terminate two by two in a common denticulate band having an indeterminate number of teeth representing fingers, usually six or seven (Figs. 56, 61). The lower limbs in both forms of the figure are the same, with crescents for thighs (the concavity, curiously enough, being upward), while the lower legs are directed inwards towards each other at a sharp angle with the thigh. In both cases the figures are outlined with single or double denticulate lines, this being a common form of border for the divisions, large or small, of the design in all parts of the “paddles.” This feature of the decoration is known, in the case of the Hervey Islands adze handles, as nio mango, “sharks’ teeth.” Another difference in the treatment of the figures in the two forms of the butt is seen in the heads. On the flat butts these are crowned with incised lines in the form of segments of concentric circles or ellipses, forming a series of arches the ends of each of which seem to be supported by the hands of the crouching figures (Fig. 61). The heads of the figures on the conical butts bear on the forehead each two large discs or buttons carved in bold relief (Fig. 60.) Stolpe calls these “eyes,” and the design consisting of concentric circles which covers the shaft and blade of Fig. 1, and which he considers to be a repetition of these discs, he calls the “eye pattern.” That they are not intended to represent eyes may readily be seen from an examination of Figs. 58, 59, and 60, where the eyes show clearly beneath the prominences on the forehead. The so called eyes on the shafts and blades may be derivatives of those discs which are decorated in the manner of the two on the left in Fig. 60.

Museum Object Number: P4817

Since these protuberances are not representations of eyes, what are they intended to represent? Structurally, they seem not to be merely an excrescence on the forehead but to enter also into the sculptural treatment of the portion of the head behind it and them, as they might do in an attempt to represent a roll of hair on each side of the head terminating anteriorly in a flattened coil. That they are treated as a separate element in the carving of the whole top of the head may be seen from Figs. 60 and 62, the latter being a view from above of the butt of the handle of a “paddle” which, in the former, is seen from the side. I do not know of any description of Austral Islands coiffures, but the arranging of the hair in knots on different parts of the head was customary in that part of the Pacific. Thus we read of the Tahitians: “Frequently [their hair] was . . . wound up in a. knot on the crown of the head, or in two smaller ones above each ear.” Again: “The men generally wore [their hair] long, and often fastened in a graceful braid on the crown, or on each side of the head” [Ellis, op. cit., i, 132, 135]. Cook [II, i, p. 309] notes a similar arrangement of the hair in the Marquesas: “Some have their hair long; but the most general custom is to wear it short except a bunch on each side of the crown, which they tie in a knot.” In Ulietea one’s own hair was enhanced by that of others. “The women [dancers] had on their heads a quantity of tamou [or plaited hair], which was rolled and flowers of gardenia were stuck between the interstices, making a headdress truly elegant ” [Journal of the Right Honorable Sir Joseph Banks (ed. Hooker), p. 119]. Tamou, says Banks, was “an ornament [which] they value more than anything they have” [loc. cit.]. Much of Hawkesworth’s edition of the “First Voyage” of Cook is a mere transcription of the Journal of Banks, who was a member of the expedition. It is interesting to notice that the denticulate ornamentation on the top of the butt of the “paddle,” Figs. 60 and 62, which emphasizes the sculptural division of the tops of the heads of the human figures into three lobes, is distinctly suggestive of the braiding of hair, and it is continued in the design of concentric circles in the middle of the upper surface, while this rosette is practically identical with those on the handle and blade of the same object (Figs. 55, 60, 63). It may be that the double row of “shark’s tooth” carving with which some of the knobs are marked represents an arrangement of braids in layers rather than in coils as the more usual raylike disposition of the markings (in some cases suggesting a whorl as coiled braids might be expected to do) seems to indicate. Such a disposition of braids in layers, or long scroll-like coils, is perhaps also indicated in Fig. 58 and in Fig. 59. In the latter, the denticulations occur on one margin only and the suggestion of a braid bent back on itself, rather than coiled, is clearly apparent.

Museum Object Number: P4817

Image Number: 3

What was stated above (p. 185) as to the relation between trapezoidal butts and intaglio carving, conical butts and carving in relief, does not hold universally for the flat or trapezoidal butts. On some of these [cf. Fig. 64] the figures are represented in relief in precisely the same manner as on the cone shaped finials. If the difference in the style of butts corresponds to different places of origin—different islands within the Austral group—a point which is not satisfactorily determinable from the attributions, this departure from rule might easily be due to borrowing. Intaglio carving, at any rate, appears to be confined to flat butts, and the relation between intaglio carving of the heads, the crowning of these with the peculiar arches already mentioned, and uplifted hands also seems to be constant.

I am indebted to Mr. C. C. Willoughby, Director of the Anthropological Section of the University Museum of Harvard, for drawings and descriptions of two headdresses (as distinguished from forms of coiffure) of natives of the Austral Islands, which are now in that Museum. One of these is apparently of the form described by Ellis [i, 298] : “The most elegant headdresses . . . were those worn by the inhabitants of the Austral Islands, Tubuai, Rurutu, etc. . . . Those used by the natives of Tubuai, and High Island, resembled an officer’s cocked hat, worn with the ends projecting over each shoulder, the front beautifully ornamented with the green and red wing and tail feathers of a species of paroquet.” Making allowance for a degree of conventionalization corresponding to that exhibited in the representation of the figures themselves, there would seem to be little room for doubt that, as Mr. Willoughby thinks, the arches which surmount these figures on the flat butts are intended to represent the headdresses of Tubuai or of High Island (Raivavai). And that great importance was attached to the headdress in many parts of Polynesia is well-known; a striking instance is reported from the Society Islands by Ellis. Speaking of warfare in the Islands, he says: “When the army of the enemy has come in sight, they used to look out for the fau [a sort of helmet worn by distinguished personages] rising above the rest of the army, and when they have seen one, pointing to it, animate each other by the exclamation, ‘The man with the fau; ha! whosoever shall obtain him, it will be enough'” [op. cit., p. 300].

Museum Object Number: P4817

Image Number: 4

Museum Object Number: 29-58-10

Image Number: 17

The other headdress in the Museum at Harvard corresponds closely to a “Rurutuan helmet” described by Ellis [p. 299]. It has the form of a cap decorated with bunches or rosettes of feathers, which Mr. Willoughby regards as being probably the prototype of the discs or knobs for which I have suggested above the possibility of a different origin. The identification of these particular features of the decoration of the “paddles” as headdresses would point to the island of Rurutu as the place of origin of those of the implements which have conical butts and to Tubuai or Raivavai for those with flat butts. All these islands are in the Austral group; and contact, friendly or hostile, would account for the mixture of styles which is exhibited in the occasional appearance of heads in relief on the trapezoidal handle butts. Such contact is in any case evident from the otherwise general conformity in shape and in style of decoration of these objects. The distinctions already pointed out may be due to a relatively late differentiation, and. the mixture of styles to a still later tendency towards a return to uniformity, caused, perhaps, by a renewed frequency of communication.

Various conjectures have been made as to the nature and use of these elaborately carved articles. There is no decisive authority for describing them as paddles, though this designation is suggested by their shape. Stolpe considers that their comparative frailty and great variation in size does not admit of their being so described. He suggests tentatively that they may have been used as standards or emblems in ceremonial dances, such implements being known to other Pacific islanders. He points out objections to this hypothesis, however, and especially the existence of other objects decorated in a precisely similar manner, notably food scoops or ladles, such as that figured here (Figs. 65, 66). This, on the other hand, does not appear to be a fatal objection. There is no reason why two distinct classes of ceremonial objects, having different functions, should not be decorated in a similar way. If the symbolism which is embodied in the ornament represents attributes of a god or hero, there is no apparent reason why the same divinity should not, for instance, be celebrated both in dances and in feasts. L. Serrurier, in a criticism of Stolpe’s monograph [Internationales Archiv fur Ethnographie, iv, 1891], is “disposed to think that the paddles . . . were decorated with . . . ancestral carvings after the death of those of whom the paddle was the principal implement [since they spent so much of their time on the water], and that the artist modifying his design during the work according to his fancy, there resulted a diminution of the total bulk. This would also explain the abundance [in Museums] of these engraved objects and the rarity of those, which, being in use, are bare of all decoration.” The objection based on the variety in size Serrurier meets by supposing that the smaller of these “engraved objects” were children’s paddles. This is hardly satisfactory, for the range of sizes is too great to be accounted for in this way in regard to an implement for which practical considerations commonly dictate fairly well standardized proportions.

Museum Object Number: 21774

Image Number: 7

But they may have been intended as imitations of the paddles which were in practical use by “those of whom the paddle was the principal implement.” This is a point which seems to have been overlooked by both Stolpe and his commentator. Yet the analogy with the Hervey Islands adze handles, which, so far as the nature of the decoration common to both groups of objects is concerned, Stolpe employs to such good purpose, is surely as cogent here. These adze handles, as Stolpe points out, were most probably of the nature of memorials made to ancestors, and used, in the first place, as mounts for the stone adze blades which had been the property of ancestors so honoured. The forms which these handles assumed were fantastic and obviously not intended for any purpose of utility. A similar process of degeneration, from the utilitarian standpoint, may have transferred the paddles from the utilitarian to a commemorative, possibly also ritual, sphere. A parallel may perhaps be seen in the genealogical staves of the Maori of New Zealand. In these the head of the staff represents the figure of an ancestor, a human figure carved according to the conventions characteristic of that branch of the Polynesians, while each generation in the line of descent is represented by a prominence between two notches. While this is little more, apparently, than a mnemonic device, it is to that extent at least commemorative of ancestors to whom divine honours were accorded.

Museum Object Number: 29-58-10

Image Number: 18

The diverse forms which the representations of deities (whether these representations were regarded as themselves gods, or merely idols, or as enshrining temporarily or permanently the gods) assumed in the southeastern Pacific agree often in the peculiarity that a number of more or less clearly recognizable, though highly conventionalized, likenesses of minor divinities are carved in groups on or beneath a figure representing a major divinity, which is commonly larger and in the representation of which conventionalization is less marked. The outline presented by the whole object is sometimes such that it appears to have no more than a merely decorative function, and a rather close examination is necessary to distinguish the forms of gods made by man in his own image. It may well be that the “paddles” of the Austral Islands are such gods, or god containers, in which the great gods, great enough to be pictured with as near an approach to realism as a sacred convention would allow, look down on the host of little gods for whose representation a few strokes would suffice. Tiki-tiki tangata—god men or man-gods—the line between human and divine was not very rigidly drawn in Polynesia; where the chief had often many attributes of godhead, not always only posthumously conferred. And so the transition need not be difficult or strained, from a memorial paddle to a divine emblem or to a god enshrined in wood or even transubstantiated there.

Museum Object Number: 29-58-10

Image Number: 16

The carved figure on the handle butts is in the large majority of cases represented as female. Where the triangular pendent breasts are omitted, this is probably through carelessness or inadvertence; in Fig. 56, where they are missing in several cases and are very small in others, it can readily be seen how easily they might become absorbed in the shark’s tooth ornament. In this connection it is to be remarked that tangata means “man” in the wider sense of an individual of either sex. And while tiki in eastern Polynesia may mean either “god” or “image of a god” [U. S. Exploring Expedition, Ethnography and Philology, Horatio Hale : Polynesian Lexicon, p. 333j, it is a suggestive fact that in some places in this region Tiki is the name of the first of human ancestors, and is in Mangaia of the Hervey group a woman.

The beauty of the carving of the blades and shafts of the implements here illustrated is not due to a variety in the elements of the design, but to their tasteful grouping and to the precision with which the carving is executed. The elements are few, indeed, consisting, first, of chevrons placed, sometimes, in simple rows as such, but more often opposed and conjoined in such a way as to form rows or tiers of lozenges bisected by straight lines. These are the last vestiges of the legs and arms of the more realistically represented figures of the butts. Then there are groups of superimposed small demilunes, representing either the “cocked hats” of the realistic figures, their crescent shaped thighs, or, perhaps their eyes, which, as Fig. 4 shows clearly enough, are often represented by such markings below the raised discs on the forehead. A third element is the rosette which was referred to in the description of the figures. Finally, the panels, large or small, in which these elements are grouped, are usually outlined with the shark’s tooth ornament, which defines the contours of the realistic figures also. Out of these few units of design, grouped in simple combinations, such beautiful examples of the woodcarver’s art as are pictured in Figures 55, 56, and 65, the masterpieces of the collection, were wrought by craftsmen who had at their disposal, in the best period of their art, no more efficient tools than they could fashion of stone and shell and the teeth of the fish which fitly lent its name to a characteristic detail of their storied scheme of decoration. If we cannot read the tale, we can at least admire the piety and skill of the patient recorder.

H. U. H.

Museum Object Number: P2147

Image Number: 8

Museum Object Number: P4820