The terms Mohammedan Art, Arabic Art and Saracenic Art are used by different writers to describe the work of artists who flourished in the Middle East between the 9th century and the 16th century and who were still active in the early part of the 17th century.

Image Number: 207127

The term Mohammedan Art is amply justified on the ground that its manifestation grew and expanded under Mohammedan influence and by the encouragement of Mohammedan rulers. The religion of Mohammed was given to the world by the Arabs and the initial energy that made this movement a force in the world was imparted by the Arabs who during their conquests carried new ideas and set new forces to work. It is clear that the revival of art under new forms was a part of that movement and the term Arabic Art is therefore justified on that ground. The term Saracenic Art is preferred by some writers because the name Saracen was adopted by Western Europe to describe all the militant peoples of the East professing the Mohammedan faith as opposed to Christians, but the word itself is of obscure origin.

I choose for my present purpose the term Arabic Art because I wish to bring into view the fact that this vigorous growth associating itself with the stirring episodes of an adventurous military movement owes its initial impulse and directing energy to the Arabs. Arabic Art is a highly distinctive performance taking to itself a pronounced style that can be recognized all the way from Cordova to Delhi. It was an unheralded and spontaneous eruption of artistic activities thrown out from the Arabian desert by forces which were not directly associated with the artistic impulse but rather with a restless imagination stimulated by religious fervor. The result was one of the most surprising and unaccountable episodes in the history of culture. In its origin it proceeded from the most unlikely sources and yet from its beginning it was a very promising performance and in the course of four centuries became one of the most brilliant achievements in the whole realm of art. It is quite irrelevant to say that the art we call Arabic was everywhere éngrafted on local cultures and represents in one case a revival of Sassanian Art, in another of Assyrian Art, in another of Coptic Art, in another of Mediterranean Art, or that in this or that aspect it proceeded from Iranian sources, or that it borrowed from Byzantium. To generalize on these• relationships is only to state a condition that is common to all movements in the history of culture which everywhere springs from seeds already ripe and fallen to the earth. The Arabs when they left their native deserts in Arabia were not without culture and refinement hut these qualities had never found expression in creative art. They had no architecture, sculpture or painting. Their lives were primitive, barbaric and lacking in adornment; yet in their sudden military migrations wherever they touched soil rich and ancient associations connected with the Arts, the latent genius of the race blossomed and expanded with great vigour and in new forms.

Mohammed had forbidden the making of pictures and therefore so long as his followers remained orthodox the new artistic impulse had to find some other medium. This gave at once a pronounced stamp of uniformity to the products of widely separated sections and diversified surroundings. Egypt, Syria, Mosul, Bagdad, Persia, the chief centres of artistic and political activity, may have handed down local artistic traditions by which their local products may be distinguished apart but the striking fact is the uniformity of treatment that makes them one. Spain, Venice and Delhi were also centres for the cultivation of Arabic Art and even in these remoter districts its distinctive character asserts itself strongly.

Museum Object Number: NEP37

The rule prohibiting the use of pictures though not strictly observed in all times and places was never ignored by Mohammedan artists and their powerful patrons, the Kalifs and Emirs of the Mohammedan world. Animals did find their way into design but so far as I am aware these representations are never so close in their imitation of nature that they could offend as likenesses. They represent a compromise between the artist and his religion and they fluctuate between fixed conventions and mobile abstractions. Thus the prohibitions of religion were partly circumvented for the benefit of art without incurring damnation, but there was another way of achieving even more desirable results with no risk at all. The Prophet had forbidden the making of images but not their use. It was quite safe therefore to employ Christians in the invention and elaboration of designs involving pictures of men, beasts, trees and flowers. The maker could take the punishment, the faithful Mohammedan might enjoy the products of the other’s skill with pleasure and profit in this world and without penalty in the next. When therefore we encounter the use of animal or plant in Arabic Art, we have an object not necessarily made by Mohammedan craftsmen but probably by Christians employed by Emirs of the Faith who used their wealth and influence to encourage the exquisite craftsmanship that appealed to their taste and satisfied their passion for refined and sumptuous splendour in their dwellings and in their attire.

Museum Object Number: NEP37

The wearing of fine silks being forbidden to the faithful by the Prophet as a luxurious weakness, the difficulty was surmounted by running a single thread of cotton in the border of the web as it was woven, often by Christian weavers, while the luxurious silken fabric was richly adorned with figures of animals and flowers. The wearing of rich raiment was general among the wealthy and in no age or place besides have such delicate and refined fabrics been wrought for the raiment of the wealthy and powerful. The dwellings presented in their interiors the same rich and colorful effects but the refined craftsmanship was lavished on walls, ceilings and floors rather than on movable furniture for of this there was indeed very little. Cushions, carpets, a tabouret, a vase or two in recesses of the wall, a basin, a ewer and a censer were nearly all the furniture that Arab domestic life required or custom permitted. It is to the walls, ceilings and floors therefore that we must look chiefly for household decoration but as the houses of the earlier and better periods have nearly all vanished we have few complete examples of domestic decoration. Indeed early examples of Arabic Art at its best are rare and the examples which usually illustrate the design and workmanship of the artist and craftsman of the best period are in bronze, tiles, mosaics, woodwork, pottery, glass, textiles, and illuminated manuscripts.

Museum Object Number: NEP38

Museum Object Number: NEP38

Cairo was always one of the most active centres of Mohammedan culture and it is there that Arabic Art can best be traced today. In the 8th and 9th centuries Cairo saw the rise of the new culture under the Arab Governors appointed by the Kalifs of Bagdad. The 10th, 11th and most of the 12th century saw this art confirmed in the favour of the Fatimy Kalifs of Egypt whose generous patronage enabled the artists and craftsmen to work under the most favourable conditions. Under the rule of the succeeding Ayyub Dynasty founded by Saladin, the same liberal encourgement was carried on till the middle of the thirteenth century. Then came the strangest and most paradoxical period ushered in by the Mamluks. These Tartar slaves attached to the court of the Egyptian Sultans, maintained as a bodyguard in the trusted service of their masters, found themselves possessed of so much wealth of the Sultans’ gift and so much power at court that the Sultan himself became subject to their whims. At an opportune moment the inevitable happened, for the Mamluks, removing their masters in a spirit of turbulent arrogance, raised one of their own Emirs to the throne. For more than two and a half centuries these ruffian princes ruled by means of violence and intrigue, making and unmaking Sultans of their own blood as the impulse seized them. Yet it was these descendants of barbarian slaves from beyond the Oxus, a people without any artistic traditions of their own—it was from this unlikely source that Arabic Art received its greatest impulse. To these lawless usurpers Arabic Art owes its greatest perfection. Stanley Lane-Poole sums up the situation as follows. ” The Mamluks offer the most singular contrasts of any series of princes in the world. A band of lawless adventurers, slaves in origin, butchers by choice, turbulent, bloodthirsty, and too often treacherous, these slave kings had a keen appreciation for the arts which would have done credit to the most civilized ruler that ever sat on a constitutional throne. Their morals were indifferent, their conduct was violent and unscrupulous, yet they show in their buildings, their decoration, their dress, and their furniture, a taste which it would be hard to parallel in Western countries even in the present age of enlightenment. It is one of the most singular facts in Eastern history, that wherever these rude Tartars penetrated, there they inspired a fresh and vivid enthusiasm for art. It was the Tartar Ibn-Tulun who built the first example of the true Saracenic mosque at Cairo; it was the line of Mamluk Sultans, all Turkish or Circassian slaves, who filled Cairo with the most beautiful and abundant monuments that any city can show. The arts were in Egypt long before the Tartars became her rulers, but they stirred them into new life, and made the Saracenic work of Egypt the centre and headpiece of Mohammedan art.”

It is true that the Mamluks were not of the Arabic race. It is true that they belonged to an alien and conquered people but it is also true that they had been long under the tutelage of their generous Arabic masters before they themselves became the rulers of Arab Empires. We do not know that they ever produced from their own number an artist or a craftsman. We only know that the taste which they acquired under their old masters and a barbaric instinct for splendour, led them to foster the arts already created by the Arabs without changing in any respect the spirit and tradition of these earlier productions. The only change to be observed is a less literal interpretation of the Prophet’s ordinances.

With the conquest of the Mamluks by the Ottoman Turks in the early 16th century, began the decline of Arabic Art in all of its branches, and its later history is a wretched story of degradation.

Museum Object Number: NEP35

Image Number: 183134

Museum Object Number: NEP34

Image Number: 21733, 298902

Architecture

It is easy to find fault with Arabic Architecture, an art which its creators mastered but never understood. That very want of understanding is the quality that appeals through structural defects and lack of symmetry. It is the same kind of charm that claims our praises in the work of the child that somehow of its own resources manages to produce a perfectly sincere but ungainly and often picturesque imitation of the work of his elders without knowledge and without understanding.

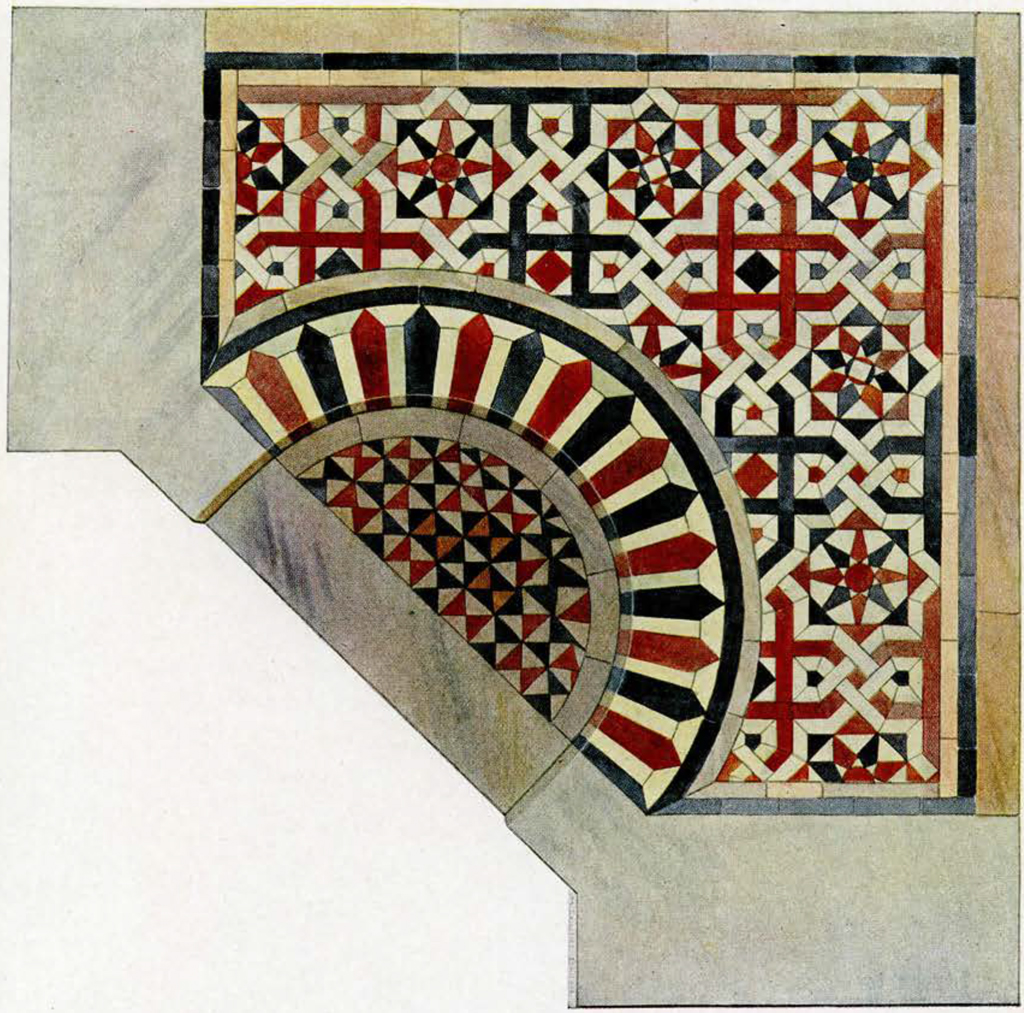

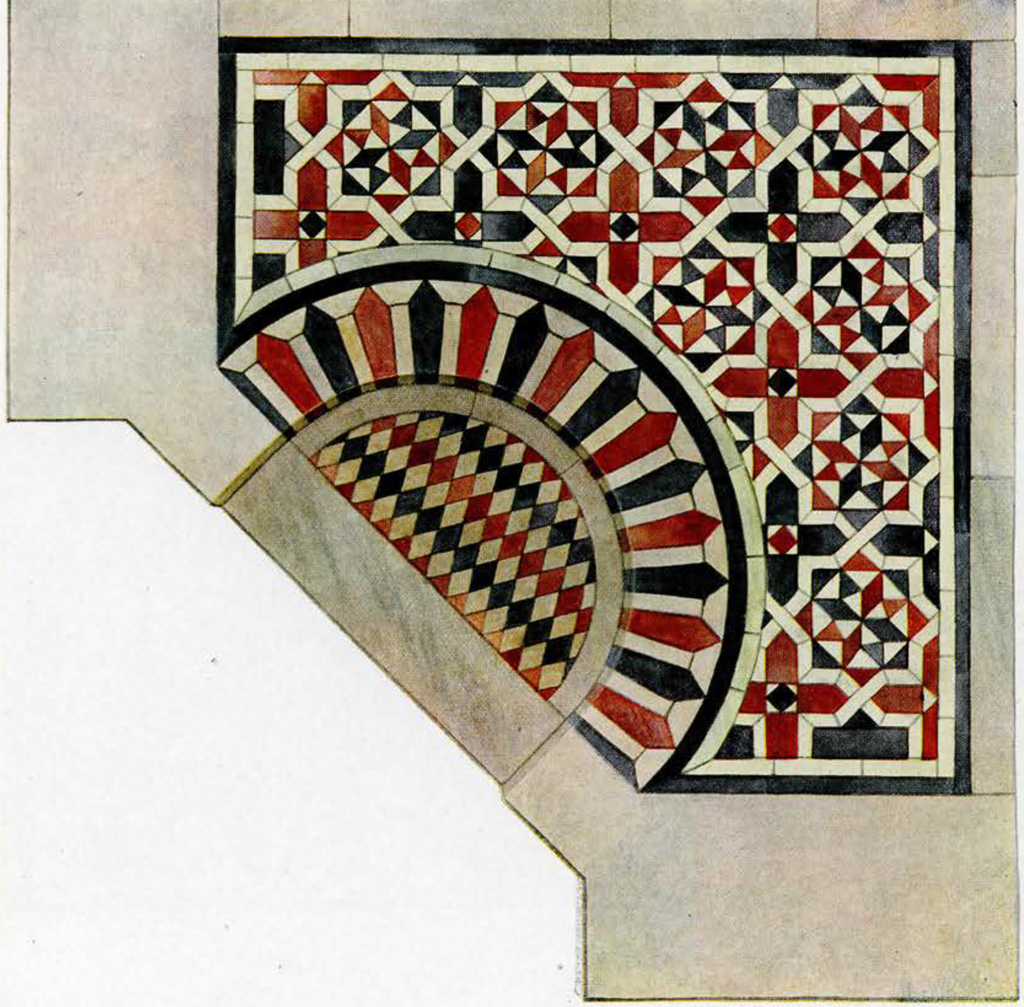

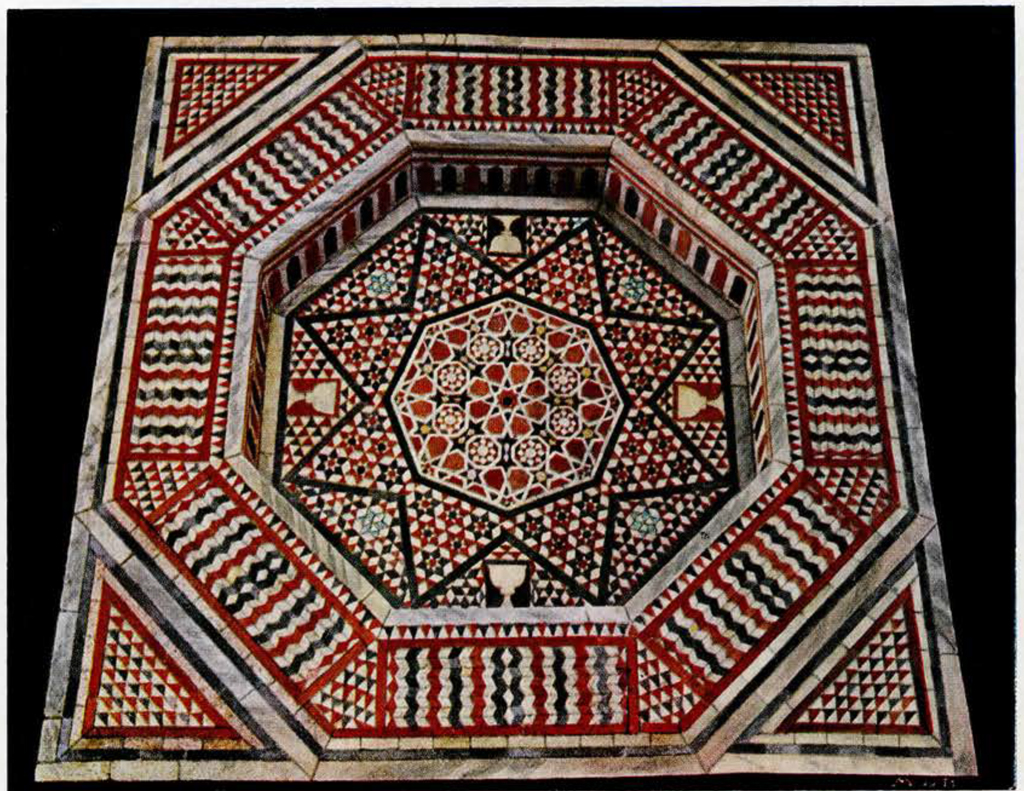

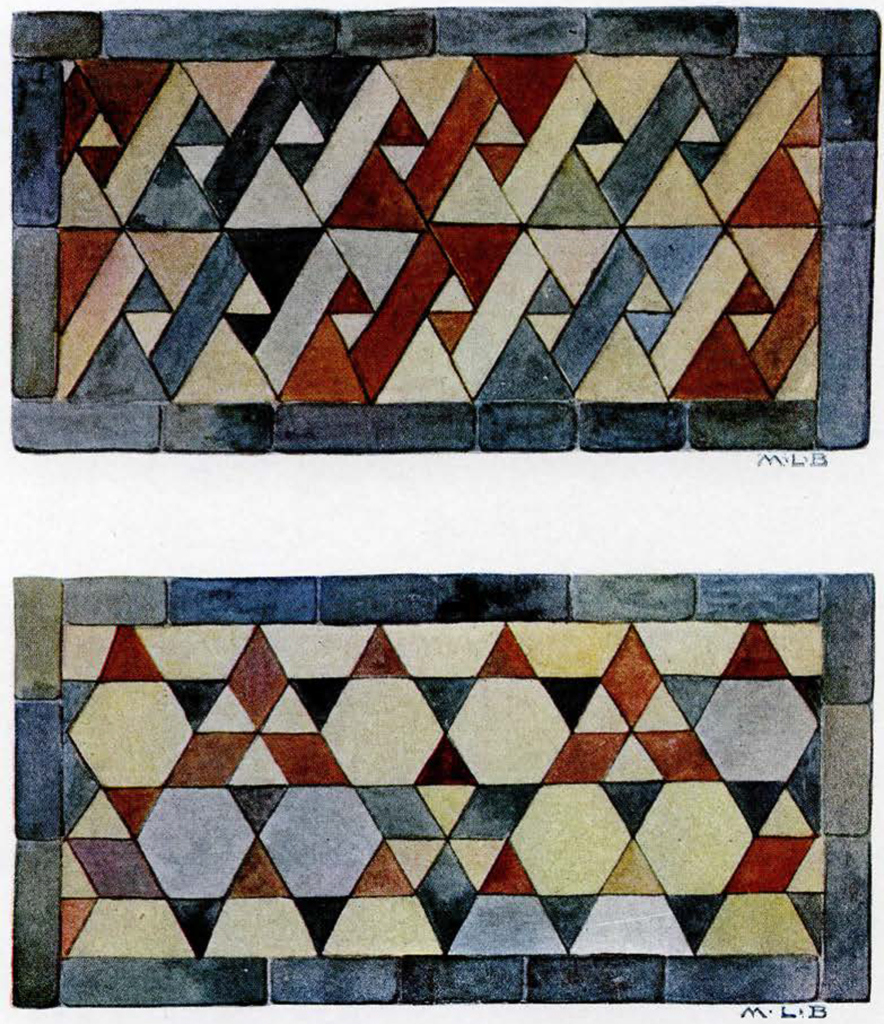

Mosaic

Museum Object Number: NEP35

Image Number: 183131

It is far otherwise with interior decoration. In this respect our admiration is due to an understanding that appears instinctive and that leaves most other historical performances in the same field far behind.

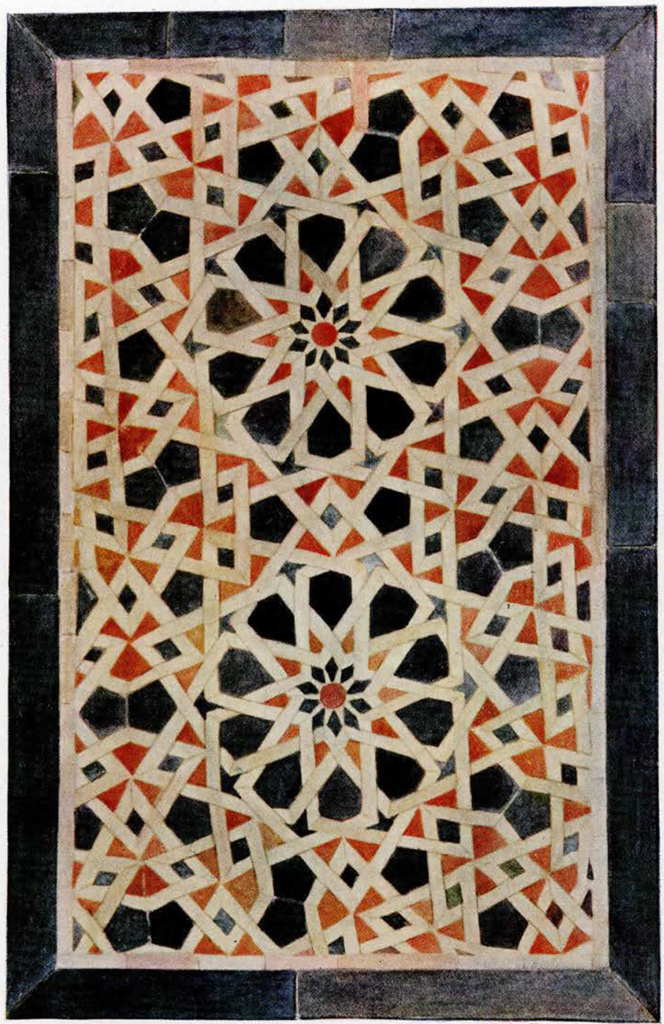

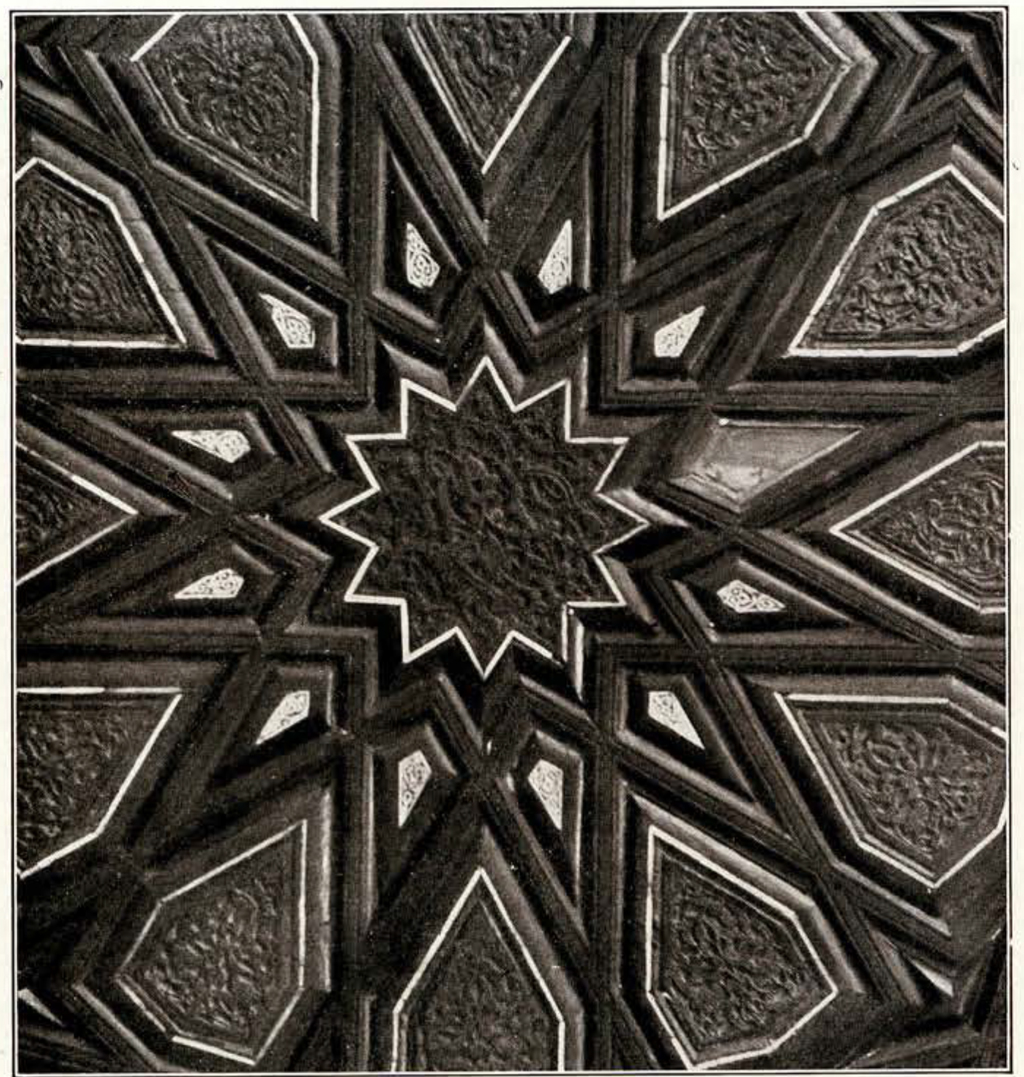

Mosaics were used in floors, fountains, and in wall decorations. Minute blocks of stone, white, black, red together with blocks of blue tile and mother of pearl were wrought into the patterns of pavement and wall panels in a great variety of design in which the intricate symmetry of interlacing lines, the harmonious division and subdivision of surfaces, and the use of soft colours are the expedients used with striking effect.

The use of mosaic decoration was chiefly in connection with floors and with dados four or five feet high decorating the walls of chamber or mosque. In its characteristic form the dado consists of slabs of white, grey, or black marble and borders of the same divided by the little cubes of different coloured stone and mother of pearl combined to form a pattern in which the geometrical motive is repeated with subtle variations to avoid monotony while preserving unity, rhythm, balance and harmony. The reception room of an Arab house had a special feature in the form of a central fountain with basin usually sunk below the floor. On these fountains the worker in mosaic often did his best work and displayed the finest resources of his craftsmanship. Other points at which mosaic was introduced were borders of doorways and wall panels entitled to special honour. A large fountain in the University Museum that I obtained in Cairo in 1919 and a smaller one obtained at the same time and place, are from Cairo houses of the 15th century and are superb examples of mosaic in its application to floors and fountains.

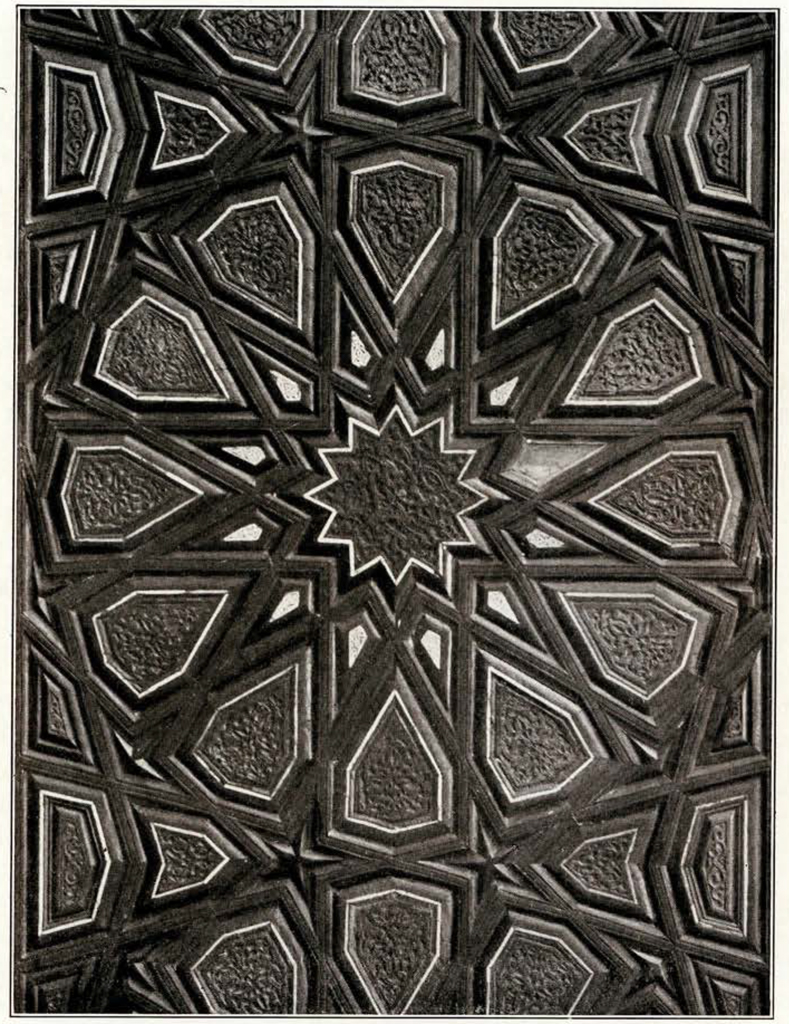

Woodwork and Ivory

Museum Object Number: NEP36

Image Number: 175594

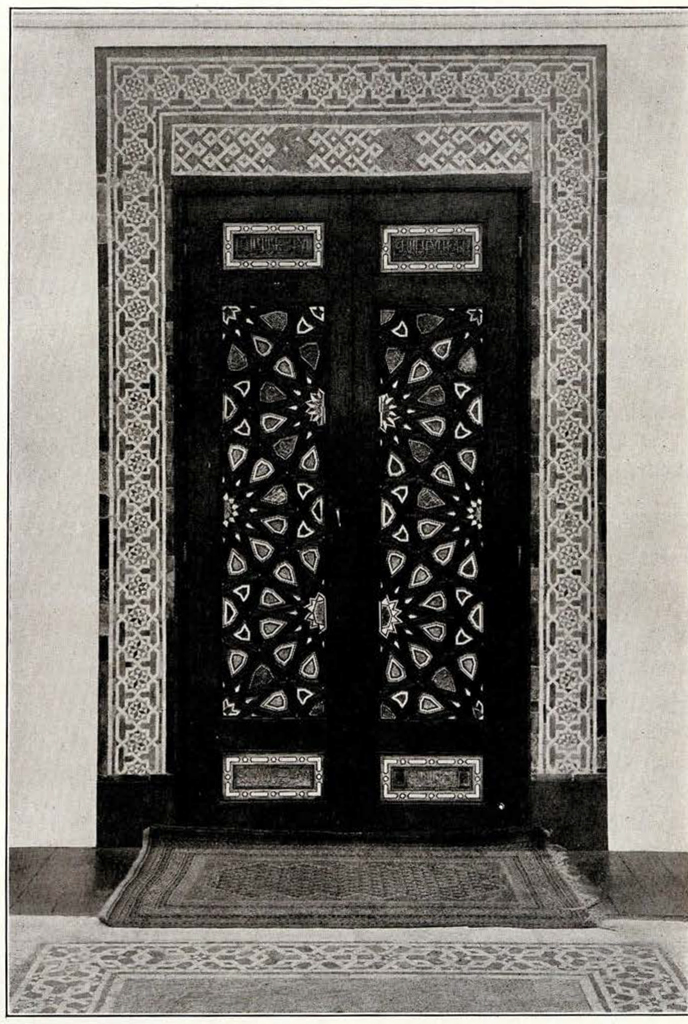

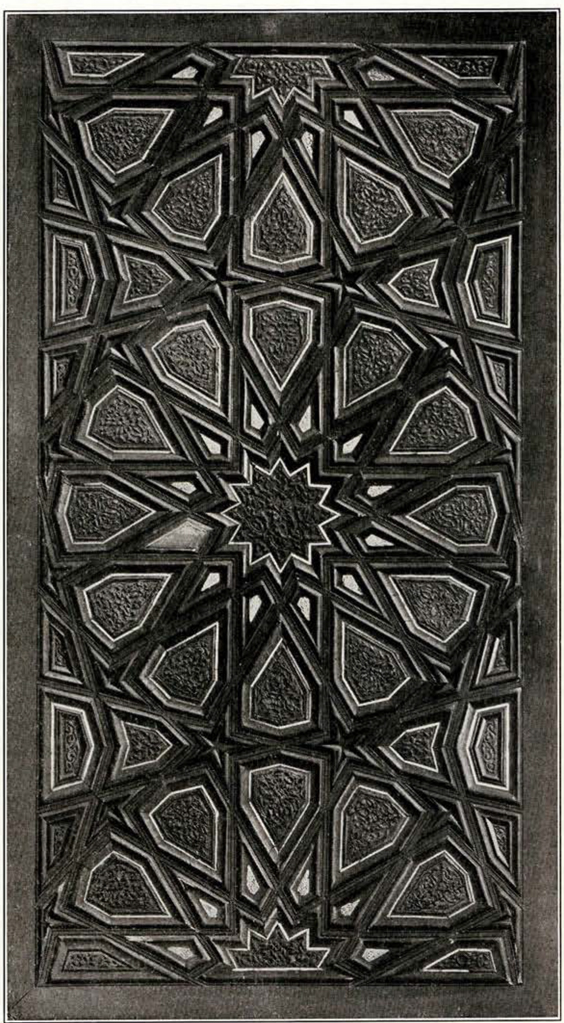

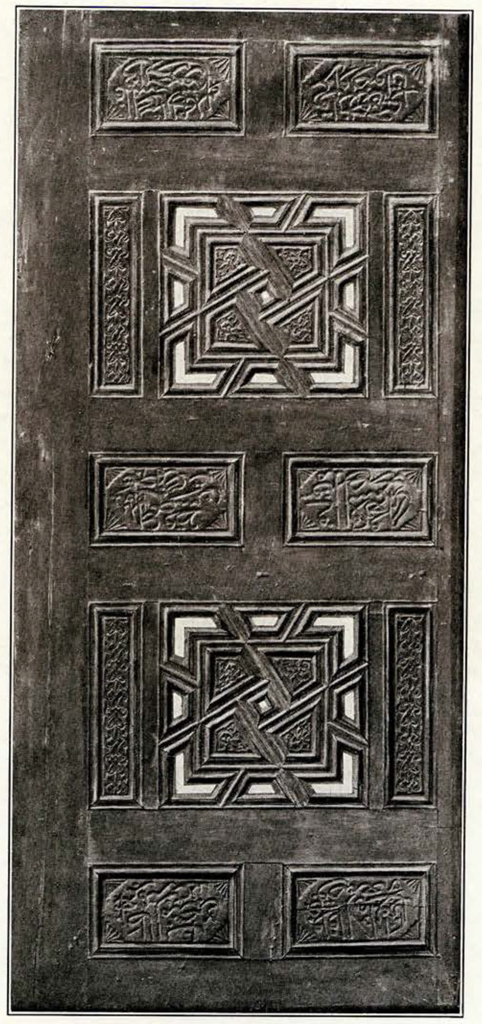

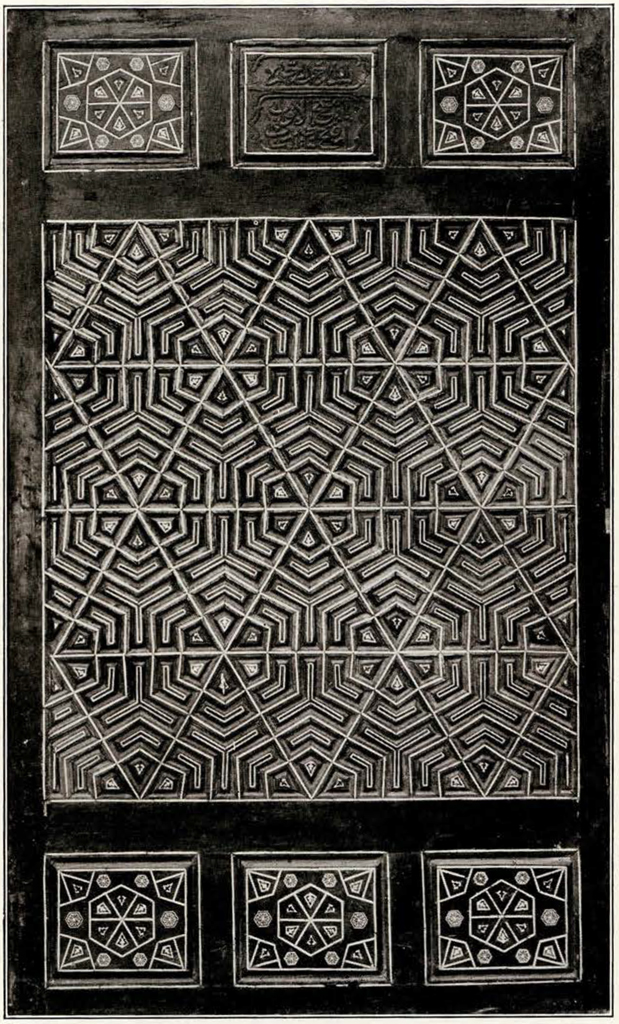

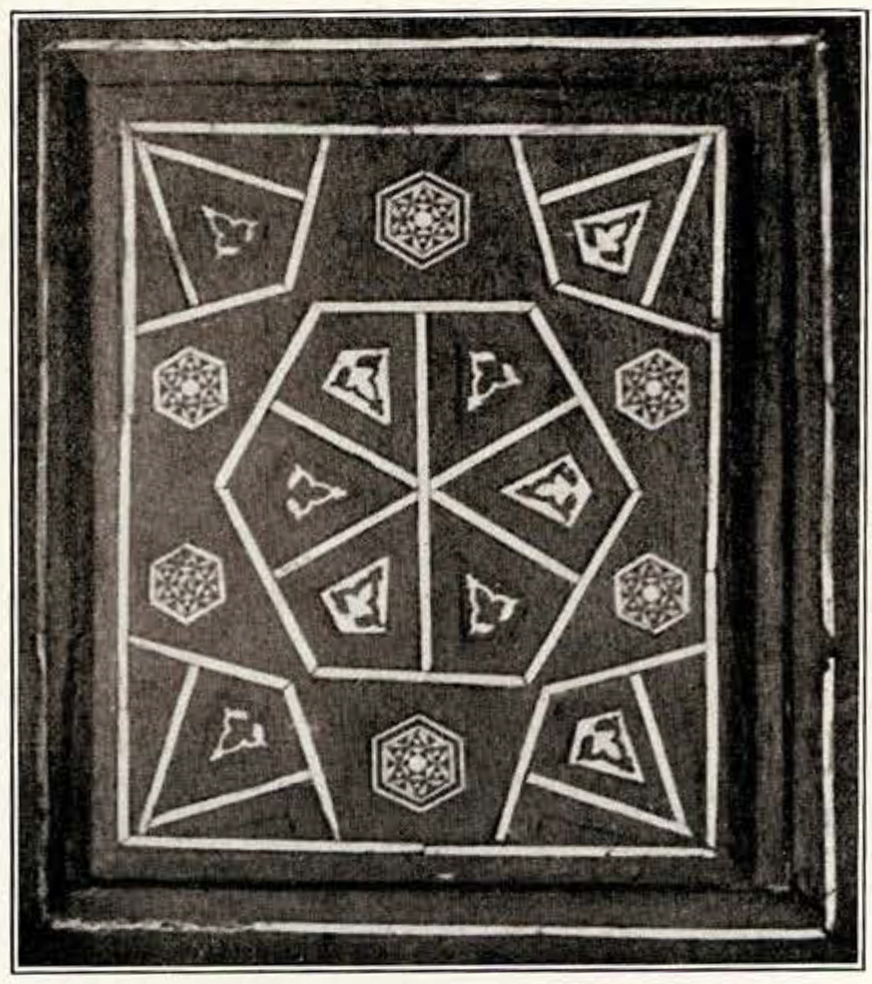

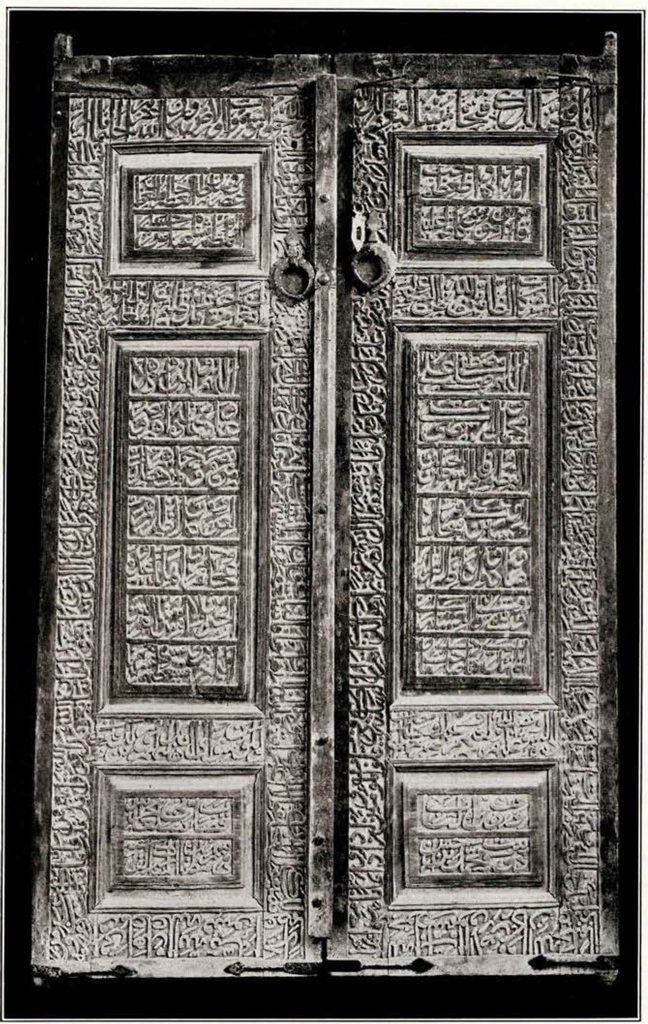

The furniture of the Arab house, palace or sanctuary was so restricted compared with the corresponding Christian usages that the domestic and religious use of woodwork and ivory, like mosaic, is largely confined to details of construction and decoration. Ceilings, doors, cupboards and Koran desks afford the best examples of woodwork from dwelling and mosque. Wood is very scarce in Egypt and the small units and numerous little panels that characterize Egyptian woodwork in particular are probably due to the scarcity of large pieces of wood. Ivory panels of various shapes exquisitely chiseled with scrollwork and interlacing patterns which skilfully avoid repetition, sometimes form the precious inlays of doors, framed in ebony and supported by other wooden mouldings and borders often inlaid with narrow ivory strips. In especially honoured positions on these Cairo doors are small panels carved with inscriptions, usually from the Koran. These inscribed panels may be of wood as in the example shown on page 16 or of ivory as in the magnificent double doors shown on page 10.

A splendid pair of double doors from Persia in the Museum collection are made each of three wooden panels framed with wood of the same kind. Panels and frames are alike filled with texts from the Koran in raised letters chiseled in the wood. These doors belonged to a shrine and were made in Persia during the 15th century.

Museum Object Number; NEP51

Image Number: 175595

Museum Object Number: NEP50

Image Number: 183133

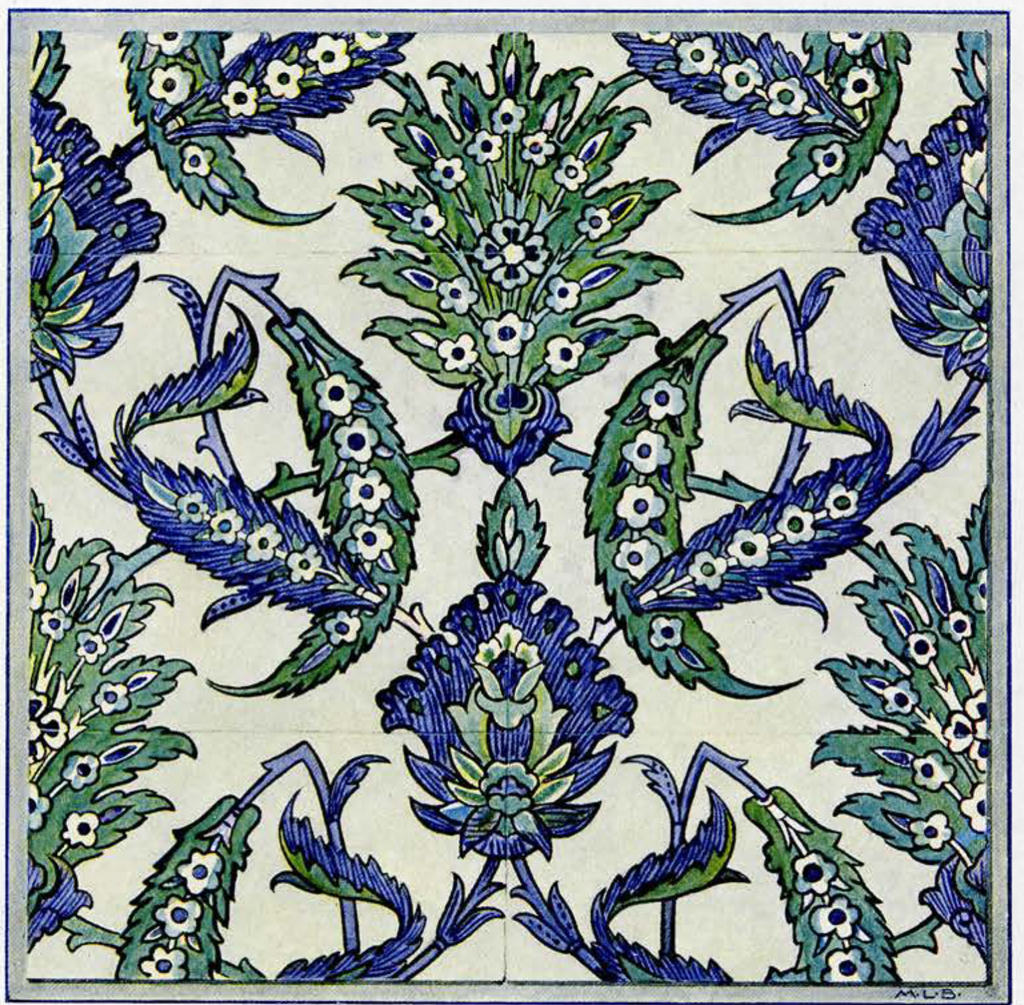

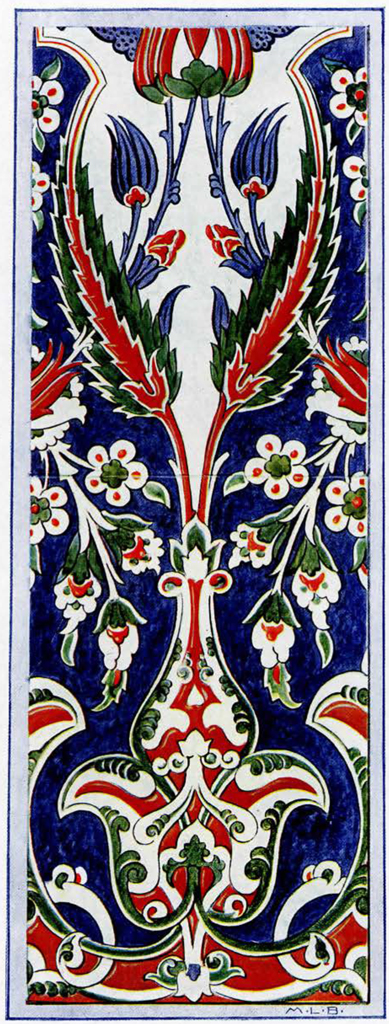

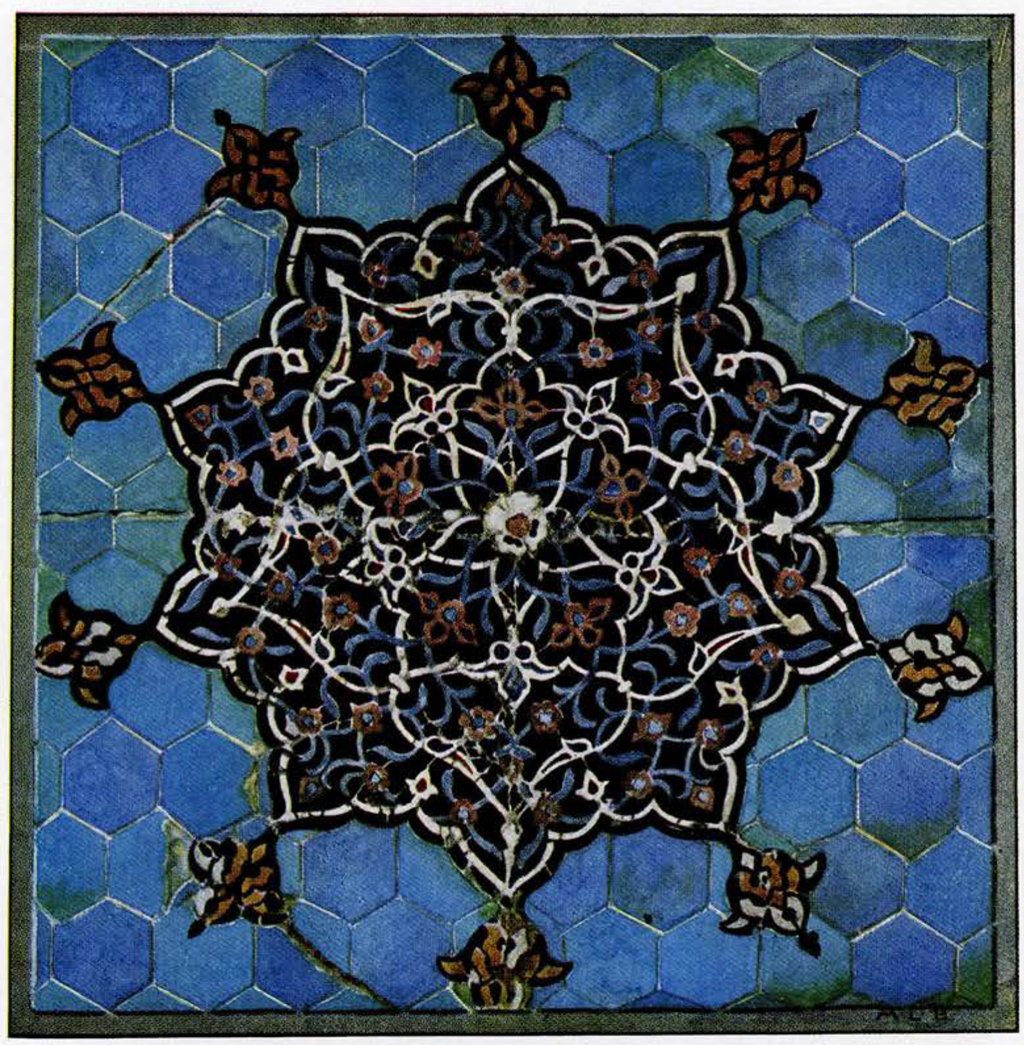

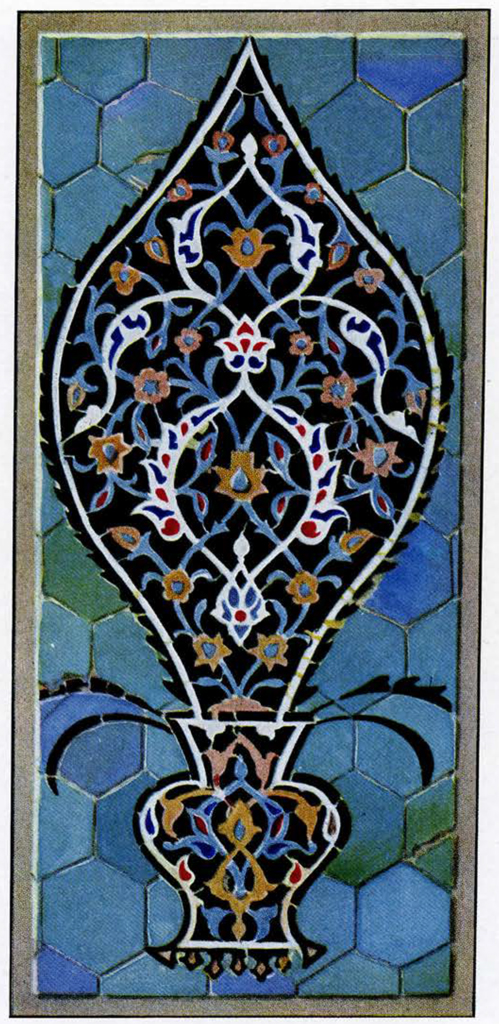

Tiles

Museum Object Numbers: NEP47, NEP48

Image Number: 174127

Among the minor arts nothing fulfills the purpose of Arabic Art or expresses Arabic taste more faithfully than the tiles that decorated the walls of palaces and mosques and that sometimes provided the exterior finish of mosque, mausoleum, fountain or palace. The Mosque of Omar at Jerusalem will be recalled as a magnificent example of the use of glazed and coloured tiles to cover the exterior of a building. The more frequent application of this decorative covering was on interior walls, especially of mosques, but also of palaces. The fabrication of tiles was cultivated at Cairo, Damascus, in Persia and in Samarkand from the 11th century. The tiles of Persia and of Samarkand are easily distinguished both as to design and as to technical process employed in the making. The Egyptian and the Syrian tile represent a common industry and a common product distinguished from the products of Persia on the one hand and those of Samarkand on the other. Till the beginning of the seventeenth century Damascus and Cairo were making tiles of good quality and the industry was passed on to Broussa and Kutahia and other parts of Asia Minor where factories were established for supplying tiles for the mosques of Constantinople. The brilliant enamelled tiles known as Rhodian were products of these Asia Minor industries, such as that found at Isnik.

The Egyptian and Syrian tile presents a flat surface painted in blue with graceful scrollwork and conventionalized foliage and flowers, all spread on a white or creamy ground and covered with a thick transparent glaze. In the Asia Minor factories the same methods obtained except that in the tile known as Rhodian, the design is produced by coloured enamels—blue and red which are laid separately on the stamped matrix of clay and afterwards finished with a thin overglaze. In Spain a similar process succeeded earlier processes about the middle of the 16th century and was practised till the middle of the 17th century.

In Persia during the 13th and 14th century and early part of the 15th were made the lustered tiles, a product of marvelous richness. The most important lustered tiles were made in large sections sometimes two feet square and of corresponding thickness. The decoration on the surface took the form of reliefs picked out in colours of exquisite delicacy which glowed with a soft metallic lustre. These larger tiles were used chiefly for monumental mosque decorations and for constructing the most sacred ornamental features such as the Mihrab. A magnificent example in the Museum came from a mosque in Veramin and is dated in the 13th century.

In Samarkhand apparently originated another method of tile decoration. Small fiat sections sometimes sexagonal are joined together to form a blue field which is pierced to receive the pieces of irregular size and shape that together form the design in varied colours. Three panels of this rare and precious technique, said to have come from Teheran, are in the Museum.

Museum Object Number: NEP49

Image Number: 174128

Museum Object Number: NEP43

Image Number: 21756, 260113

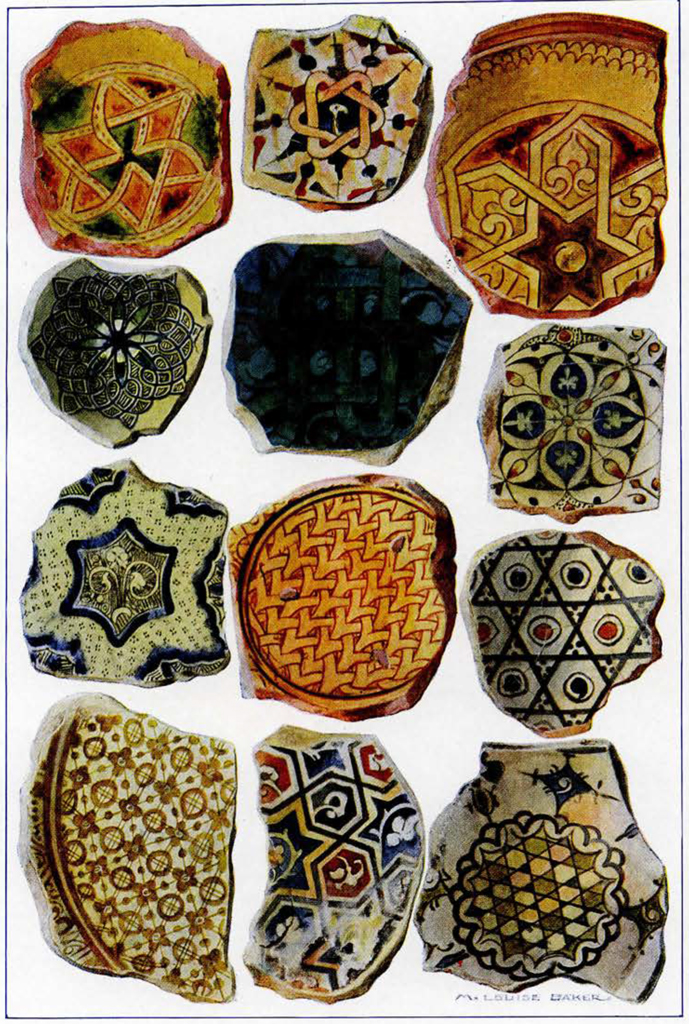

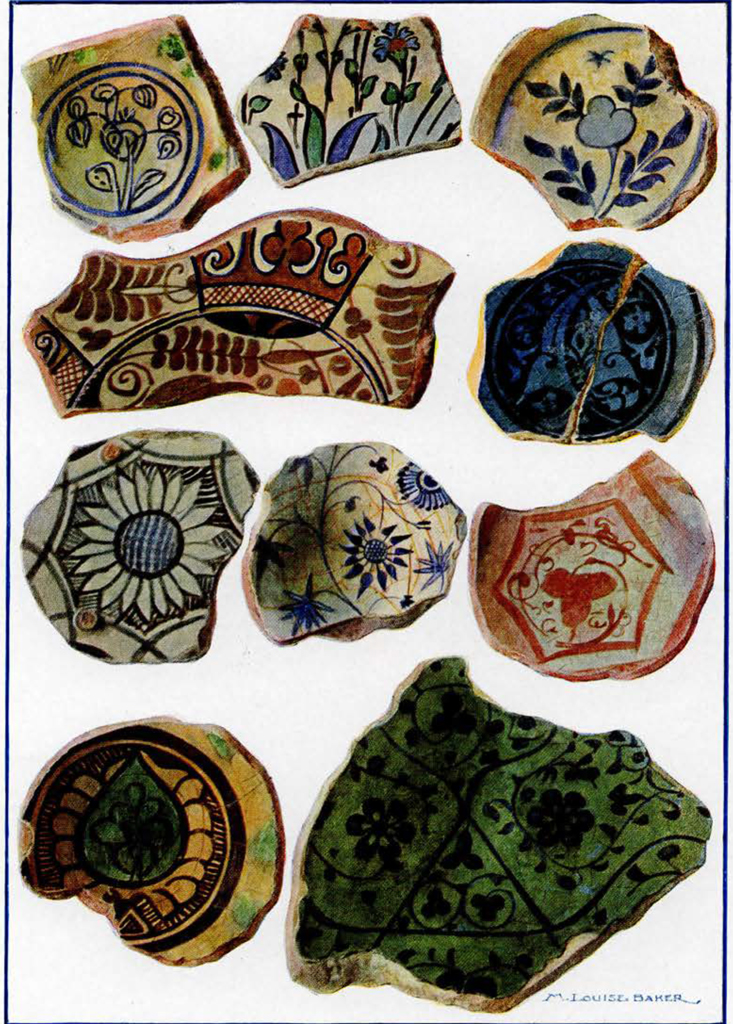

Pottery

Museum Object Number: NEP44, NEP45

Image Number: 174129, 183129

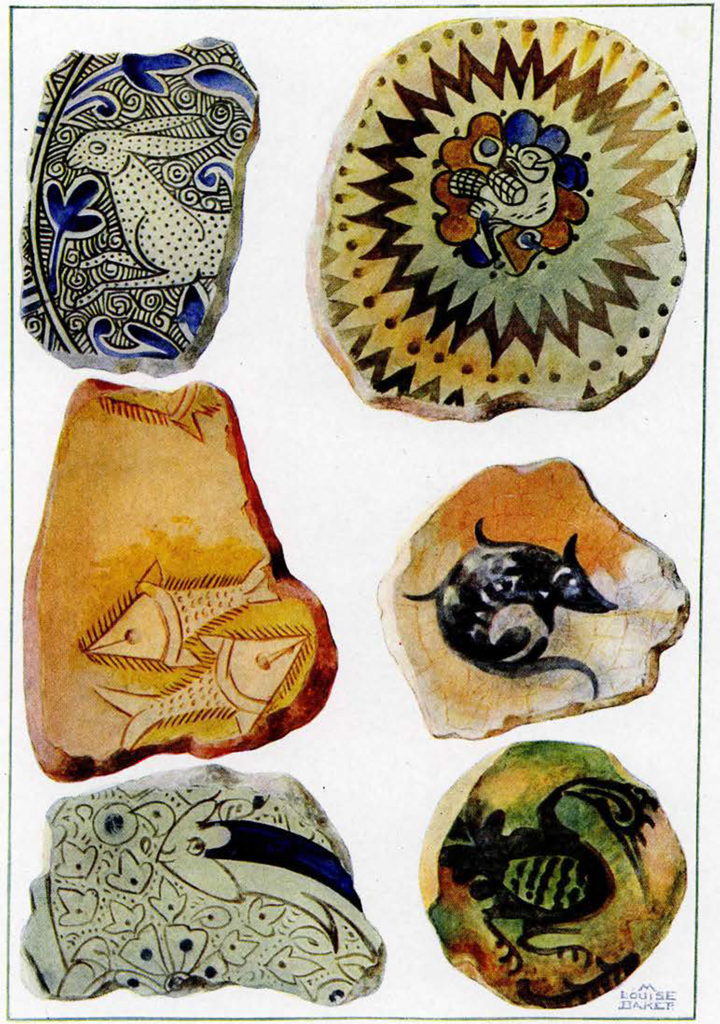

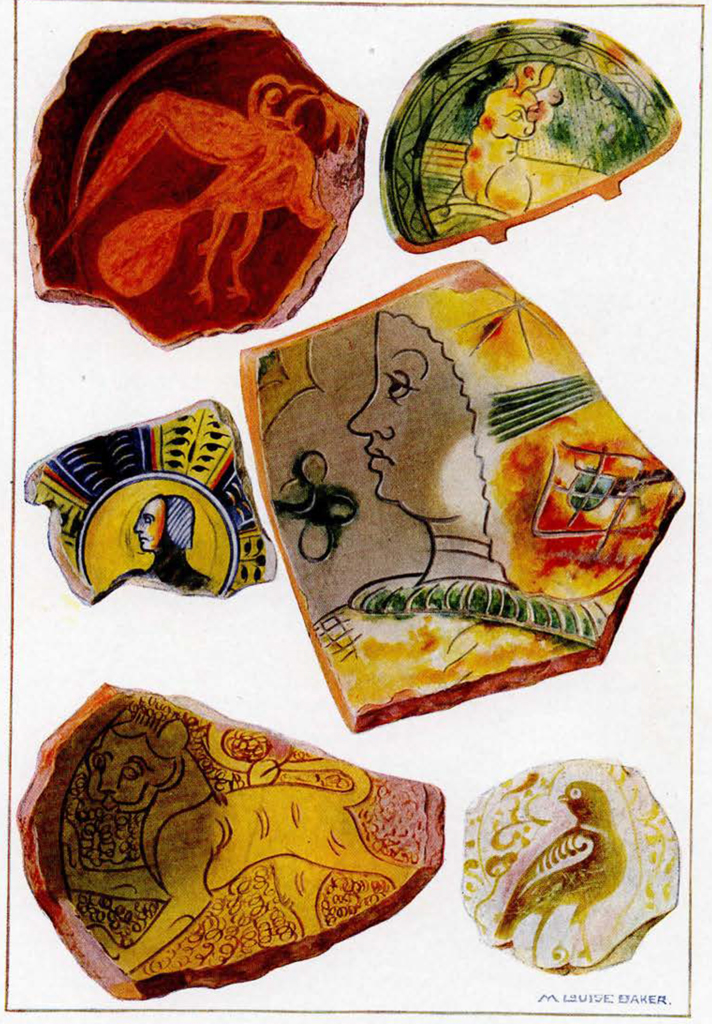

Fostat, a sand covered ruin immediately to the south of Cairo, was the first Arab town in Egypt, founded by ‘Amrin the 7th century and abandoned in the 13th century for the present capital. On the outskirts of Fostat is an extensive rubbish heap—the dump of the old city—retaining in its 60 feet of depth the debris of the domestic life of five centuries. Recent excavations at Fostat carried on under the auspices of the Arabic Museum in Cairo and with the supervision of its able Director, Ali Bey Bahgat, have yielded much interesting information about the architecture, drainage, streets and water supply of the first Arab Capital, but the most interesting discoveries have been made in the dump heap where many fragments of broken potteries have been brought to light. These fragments are of the greatest importance for the history of ceramics in Arabic lands. Though they do not reveal any of the delicate translucent varieties mentioned by Nasir-i-Khosrau, the 11th century Persian traveller, yet these discoveries confirm his description of Fostat as a great centre of the ceramic trade where the potter’s art was cultivated to such purpose that its products were justly celebrated.

That the potteries found at Fostat were made at that place is proved by the finding of the apparatus of the potter and the very furnaces themselves. Yet one of the outstanding observations to be made on any representative collection of Fostat pottery is that it contains types that are traceable to Syria, Asia Minor and to Spain on the one hand and to Persia and China on the other. It is a proof of the widespread commercial relations of the time and of the fact that artists and craftsmen in far distant parts learned from one another and handled each other’s wares.

It is obvious that some of the Fostat wares must be earlier and others later. I believe that Ali Bey who has conducted the excavations has classified the fragments on the basis of stratification observed in the dump heap. Not having sufficient personal knowledge of these excavations and not having had an opportunity of discussing the matter with Ali Bey, I have not attempted to classify the examples shown here by way of illustration. I have been content to group them as products made during a period beginning with the 8th century and ending with the 13th when Fostat was abandoned. The Museum acquired in 1919 from the Arabic Museum in Cairo a collection of more than 600 pieces of Fostat pottery representing every variety as well as the materials and appliances of the potter.

Museum Object Numbers: 29-140-65 / 29-140-413 / 29-140-75 / 29-140-338 / 29-149-241 / 29-140-412 / 29-140-349 / 29-140-84 / 29-140-420 / 29-140-189 / 29-140-417 / 29-140-409

Image Number: 171569

Museum Object Numbers: 29-140-401 / 29-140-435 / 29-140-400 / 29-140-208 / 29-140-240 / 29-140-370 / 29-140-737 / 29-140-204 / 29-140-224 / 29-140-260

Image Number: 182259

Metalwork

It is commonly stated that metal working in Arabic Art had its origin or revival in Mesopotamia during the 13th century or earlier. It is true that the earliest and best examples in modern collections can be traced to Mesopotamia and connected with 13th century traditions. There was at that time a school of artists and craftsmen at Mosul who cultivated engraving, chasing, embossing and inlaying in metals. Bronze was the favourite medium, and silver was used for inlay. As Mosul appears to have been the chief seat of this productive activity it is properly called the Mosul style, a style easily recognized and characterized by the free use of animal figures in the designs. It is probable that under the early Khalifs the rigorous teaching of Mohammed was followed in orthodox fashion by rulers and people. Though not necessarily always of pious lives they took care that in outward appearance no violence should be done to the precepts of the Koran and such prohibitions as that relating to the making of pictures were generally observed. But it is evident that before the beginning of the 13th century a more liberal spirit prevailed, means were found for accommodating orthodox views to a freer cultivation of the arts and thus Mosul metalwork presents the figures of beasts of the chase, men and horses, hounds, heraldic animals, such as the double headed eagle, water birds, throned princes and single combats, all wrought skillfully into the scrollwork composing the patterns.

Museum Object Numbers: 29-140-604 / 29-140-665 / 29-140-672 / 29-149-727 / 29-140-613 / 29-140-767

Image Number: 171568

Museum Object Numbers: 29-140-445 / 29-140-442 / 29-140-660 / 29-140-662 / 29-140-620 / 29-140-763

Image Number: 171567

Perhaps this more careless attitude towards orthodox practice may have been closely connected with the Tartar invasion and the establishment of Tartar dynasties in the place of the Arab Khalifs. These invaders, though already Mohammedans did not feel the strict regulations of Islam with the same intensity as the Arab. On the other hand their love of barbaric splendour was strong and therefore it is probable that the laws enjoined by religion against the making of images were relaxed under these Tartar rulers for the benefit of Art. It seems reasonable to suppose that the Tartar invasion bringing with it a less orthodox form of Mohammedanism was responsible for that loosening of official and popular feeling which permitted the lavish use of man and beast in the sumptuous decorations of inlaid bronze vessels.

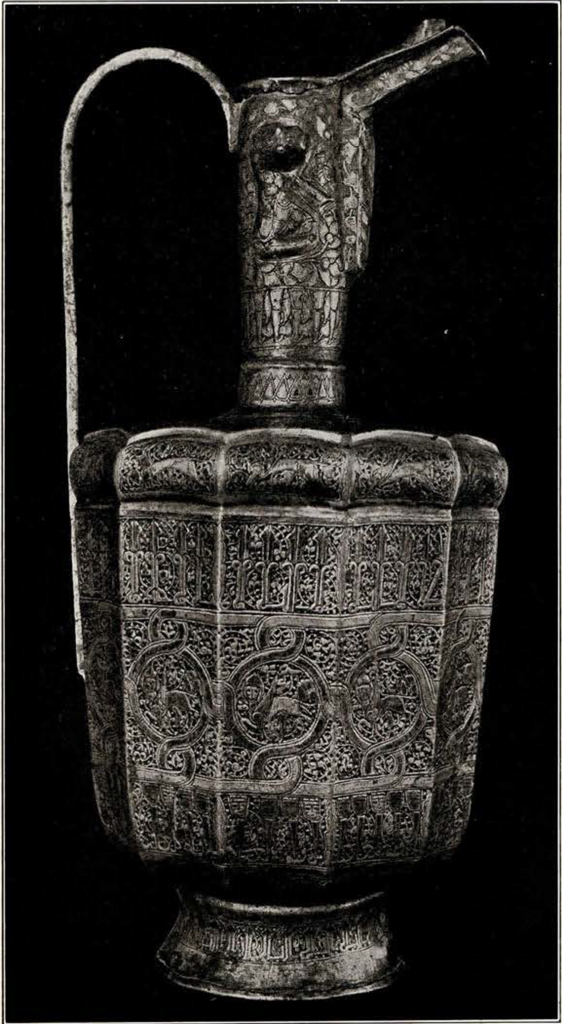

Museum Object Number: NEP38

The Museum possesses a superb example of Mosul metalwork in the form of a ewer 16 inches high, chased and inlaid with silver. The workmanship can be referred with certainty to the beginning of the 13th century and the vessel is one of the earliest as well as one of the finest examples known.

On either side of the neck is a lionlike animal embossed; on the shoulder is an animal repeated on each of the surfaces, with variations. Sometimes it has wings and sometimes not. Sometimes it has a fox’s tail, sometimes a lion’s tail and again a tail with a bunch at the end. The head in each case appears to be that of the gazelle, but the body resembles that of a lion.

Lower down is a band of inscription and in the central position is a band of scrollwork describing loops that frame the repeated outlines of another animal figure. In this instance it is a winged lion with a human head—an ancient Assyrian motive, surviving into the 13th century and reappearing under Mohammedan disguise.

The plain bands, the bodies of the animals and the letters of the inscription are all inlaid with silver. The process of inlaying consists in picking out the borders of the surfaces to be inlaid with a fine point in a series of fine indentations directed slightly outward, so as to produce a very delicate, continuous toothed undercut edge. Upon the surfaces thus prepared the thin sections of silver are laid and by pressure forced into the indentations that hold the inlay firmly in position.

The Koran

Museum Object Number: NEP39

Image Number: 21743

Penmanship among the Mohammedans was esteemed among the foremost of the arts and ranked together with poesy and scholarship as the noblest of attainments. The works of the poet and of the historian were transcribed in beautiful flowing characters with exquisite skill and unremitting pains by calligraphers who were often as famous as the poets whose work they copied. The Koran was the object of particular care and a special form of embellishment was reserved for its pages.

Besides the title pages that were so richly adorned with glowing colours and with gold in patterns laid out in intricate and lavish lines and with much virtuosity, each page of the Koran was often adorned upon the margins with medallions in gold and colours and with chapter headings wrought into arabesques and scrollwork of the same technique.

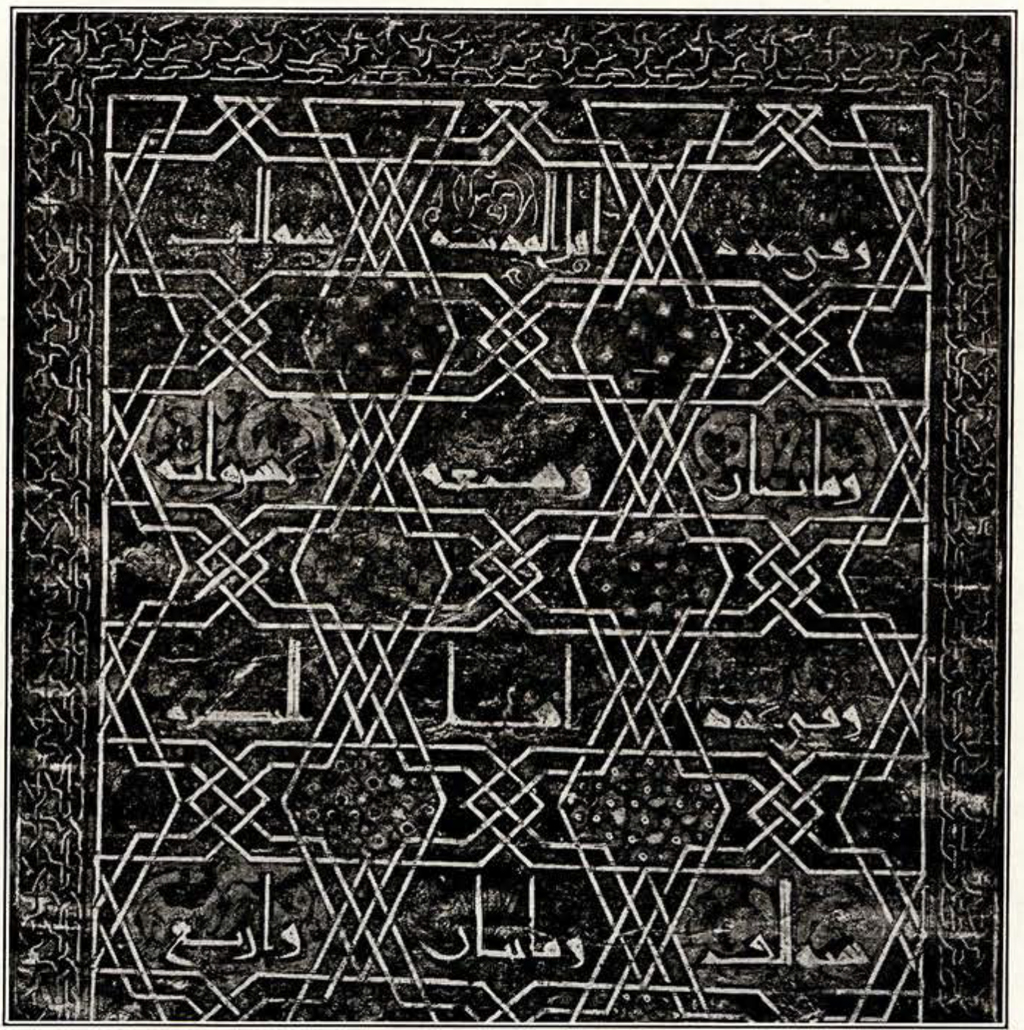

In the Museum is a Koran of the early 14th Century that I obtained in Cairo in 1919. The outer cover is leather stamped with an all over pattern picked out in gold. At either end are three full pages of illumination in prevailing gold with medallions in blue, letters and interlacing lines in white and scrollwork and floral attributes outlined in black. The main field consists of an interlacing system of arabesque forming small panels, each enclosing a portion of the Cufic text. This main field is surrounded by a single border of interlacing lines. The use of Cufic letters in this title page is of course an example of survival. It is used on the title page but not in the body of the book. The Cufic form of letters was not in general use later than the 9th Century. This copy of the Koran must be assigned to the early part of the 14th Century.

The same exquisite style of workmanship is carried throughout the medallions and chapter headings, of which there are many. The medallions and the rosettes that served the purpose of punctuation and of emphasis for the guidance of the Reader, are in ink or in colour on a gold ground. The lines are free flowing lines for the most part. The Chapter headings that occupy the width of the pages, are displayed each within a gold field upon which delicate scrolls are traced in ink or overlaid with blue. Within this field is a blue panel in which the letters are done in gold outlined in white.

G. B. G

Museum Object Number: NEP39

Museum Object Number: NEP40

Image Number: 21745

Museum Object Number: NEP40

Museum Object Number: NEP40

Museum Object Number: NEP41

Image Number: 21774