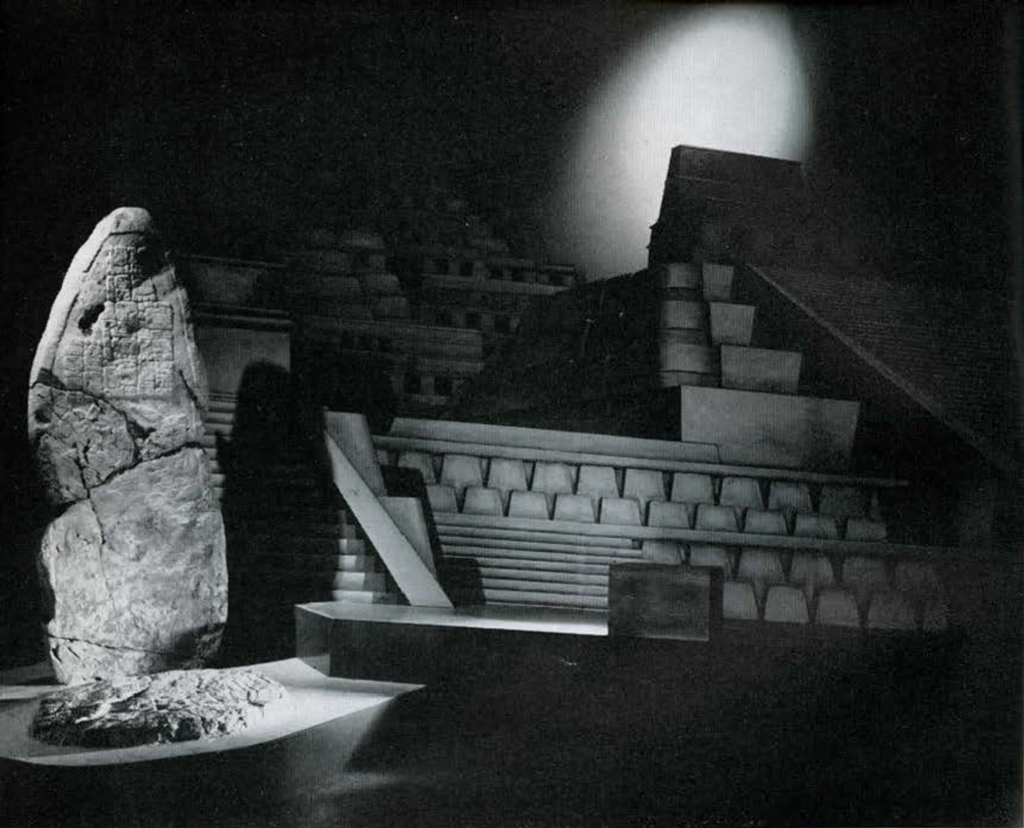

In the BULLETIN of May, 1951 (Vol. 16, No. 1) we gave some account of explorations at a comparatively new Classical Maya site called Caracol, in British Honduras, and announced our intention of returning. We did return, and with the active cooperation of the Colonial Government a considerable number of carved stone monuments were packed up and brought out from the site. As the early illustrations. show, rearrangements in the Middle American Hall have been necessary to accommodate our share, though Dr. Mason’s prize Stela 14 from Piedras Negras remains undisturbed. Horace Willcox contributes a separate piece on the practical problems involved in safely transporting heavy but delicately carved stones from the uninhabited tropical rain forest, and in re-creating whole monuments when they are found as fragments. Here I am concerned with the restored specimens as ancient works of American Indian art and science, their role in the aboriginal culture, and the general background of the operation. A fuller description and study of the findings at Caracol will appear later in our Monograph Series.

As a general rule the least eroded stones were selected for removal but, even so, time has been very unkind to some of those we brought out. Our basic purpose has been to add to the store of Maya sculpture which will escape entire destruction-if not soon by man, then eventually by rain, expanding roots and falling trees.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-6

Museum Object Numbers: 51-54-3 / 51-54-5 / L-16-382 / 51-54-2 / 51-54-4

STELAE AND ALTARS

A Maya “monument” is a stone object of considerable size. Usually it was carved according to some design, though unsculptured plain ones are not uncommon; one may guess that painted designs have been lost from the latter. Plain or sculptured, most monuments were placed in obvious relationship to ceremonial masonry platforms or buildings, or at least close to them. Sometimes stones which are actual architectural elements are classed as monuments because they invite individual attention and were obviously more than mere embellishments of a building. The distinction between monumental and architectural sculpture is not always easily drawn.

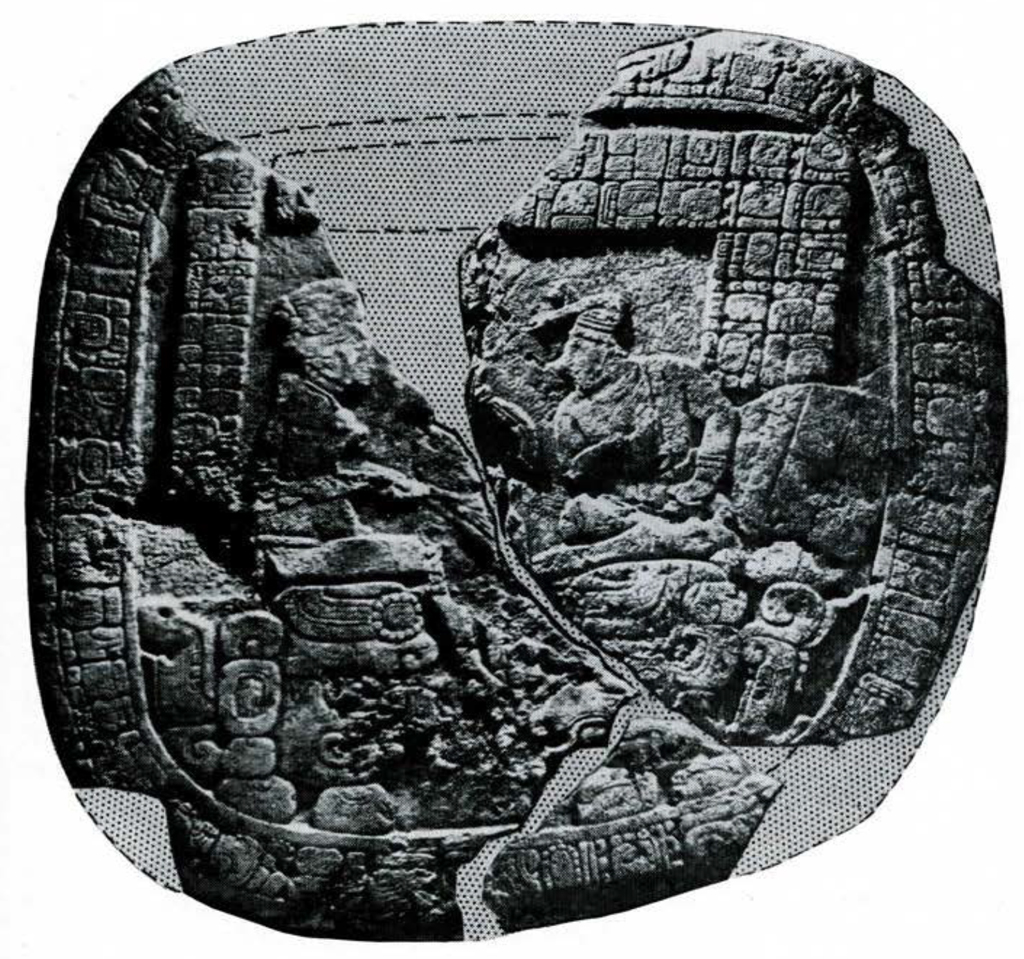

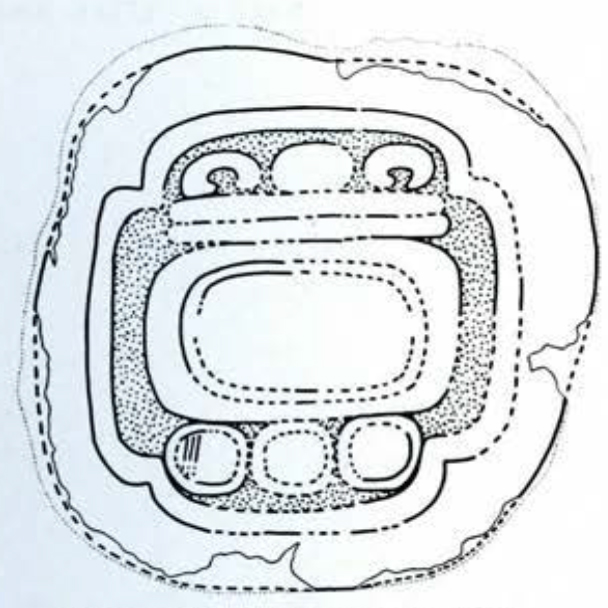

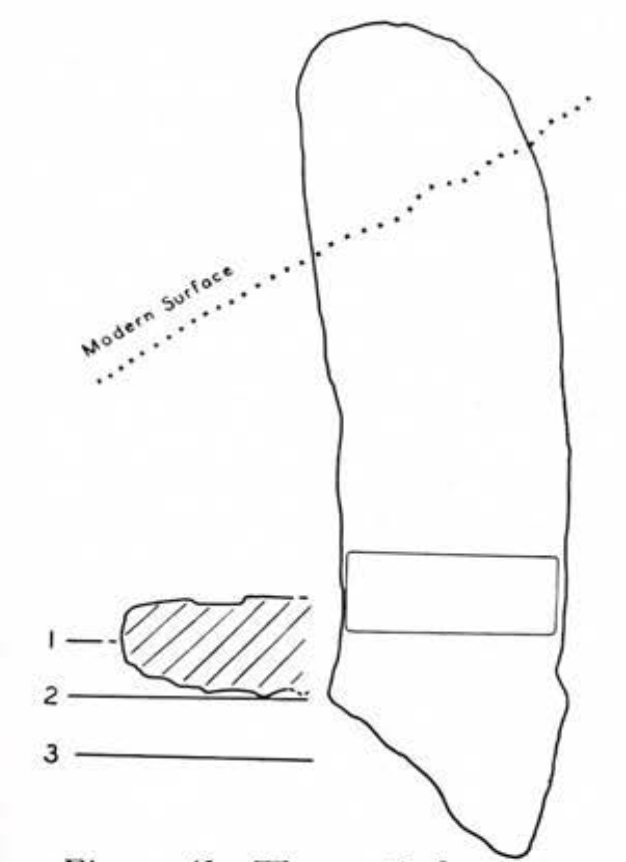

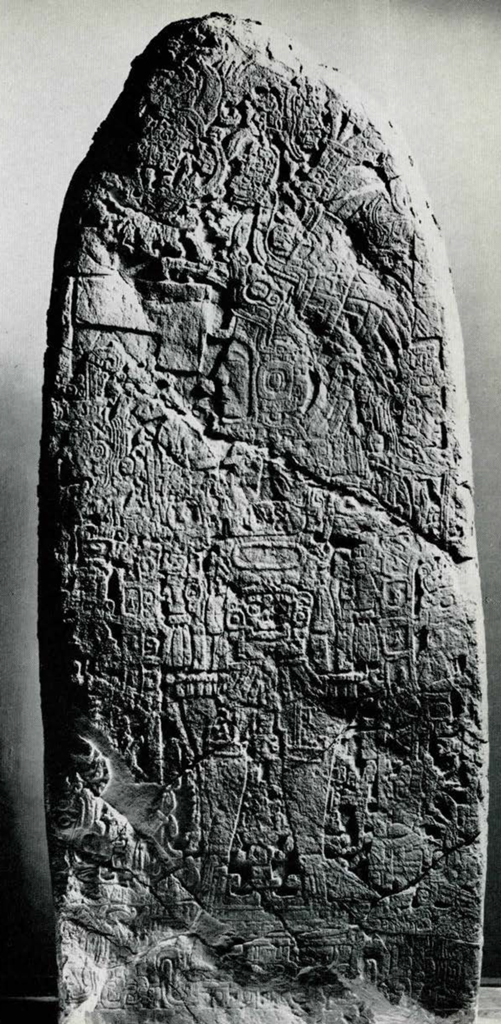

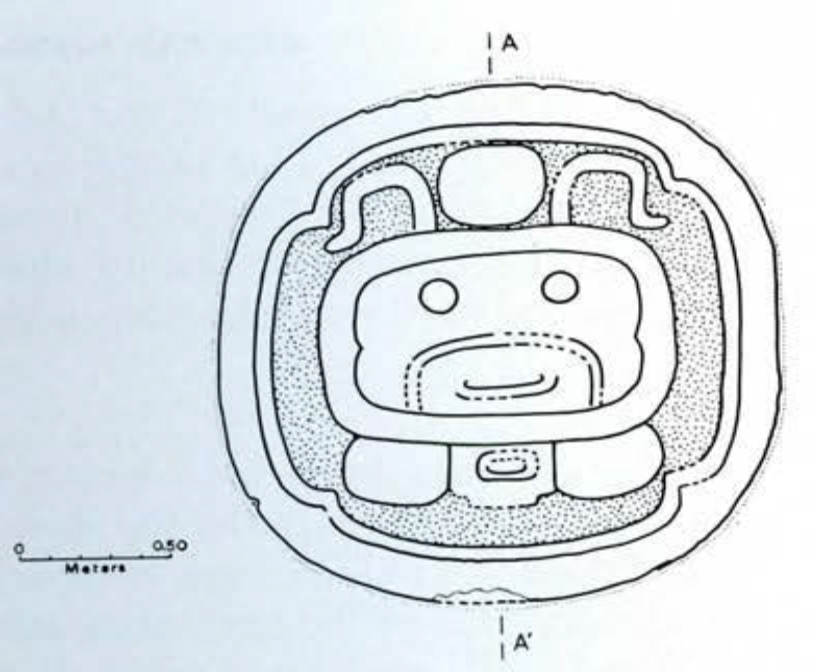

However broadly one may use the term “monuments,” the most numerous and typical form was what we call a “stela,” and next in order came various types of “altars.” Often these two types were placed together, forming a “stela-altar pair,” as in Figure l. Altar 10, shown in that figure, is typical in that it was partially embedded in the pavement, and lay flat. Rarely (at Caracol and elsewhere) the arrangement might be varied by setting the horizontal slab on legs, forming a “table altar.” Stelae were always more or less long, slender shafts rising vertically from the pavement.

When we have an altar and a stela which belong together, if both are carved, the inscription may start on one and be continued on the other, or the same dedicatory date may appear on each. With or without such confirmatory evidence, when one finds an altar centered before a stela one can be sure they were planned for and dedicated together. However, altars may be independent of stelae, and, whether they are or not, they may show designs essentially similar to those expectable on stelae. Thus, Altar 10 belongs with Stela 17, while Altar 13 seems to have been quite independent. They both carry inscriptions and representations of three human figures (Figs. 14 and 27).

Museum Object Number: 51-54-2 / 51-54-4

Later on herein there is a summary of dates on the Caracol monuments, which many readers will wish to skip. The total time-span during which such monuments were being carved somewhere in the area is about 572 years, and in terms of our chronology probably – but not certainly – this monument-carving period extended from about A.D. 552 to A.D. 889. Caracol seems to have been carving monuments during at least 315 years of this period-from A.D. 534 to A.D. 849, if the correlation with our chronology is correct. It happens that the earliest and latest known dedicatory elates at Caracol are respectively on Stela 16 and Stela 17, now in our hall. The whole collection of five stelae and three altars thus covers a very respectable minimum span of years, and differences clue to passage of time may be looked for, and perhaps established. One must be cautious, however, in reversing the process and trying to date illegible monuments by supposed time-indicating likenesses and differences. For instance, in form and size Stelae 16 and 17 are more alike than any others, yet we think they were separated by 315 years of time.

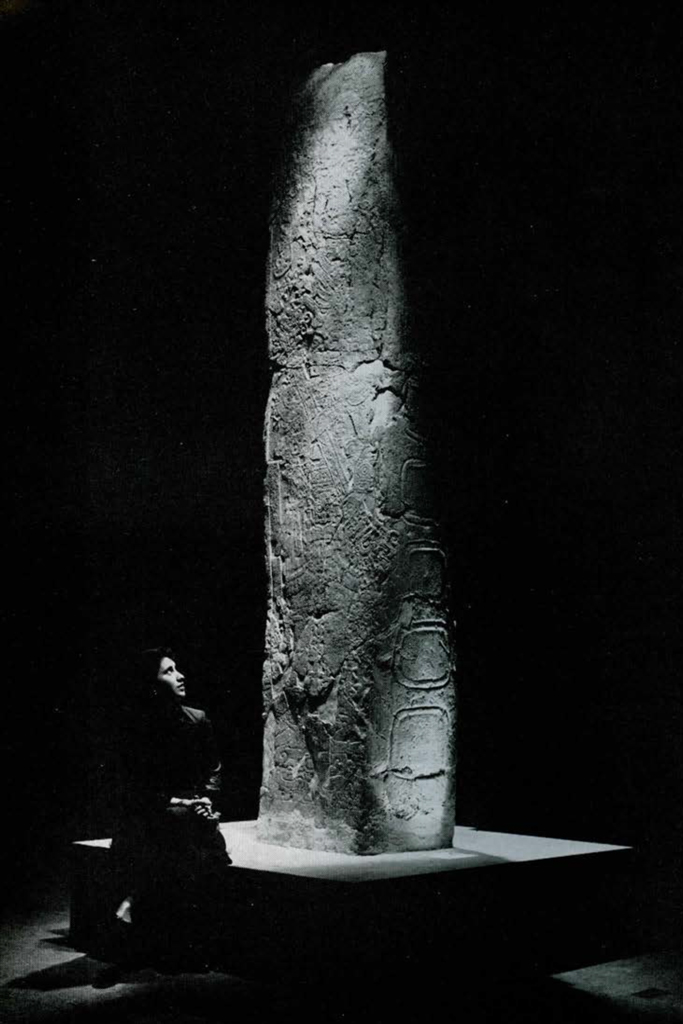

ln this matter of size and form of stelae our own monuments fairly represent the site as a whole. Stela 16 is the shortest, while Stela 6 is about as tall as any. They date about seventy years apart. The “Mutt and Jeff” relationship of these two is clear in Fig. 2. In respect to Maya stelae generally these are smallish to medium in size; but Caracol altars range from small to very large by any standard. Altars of the types represented are usually classed as “round” or “rectangular.” In a general way those terms apply here. A detailed summary of altar size and form is given later on, with discussion of probably significant variations of these basic forms.

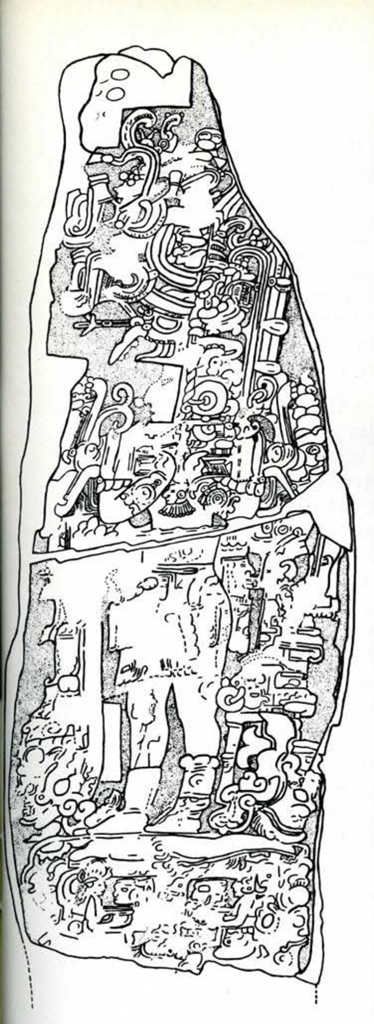

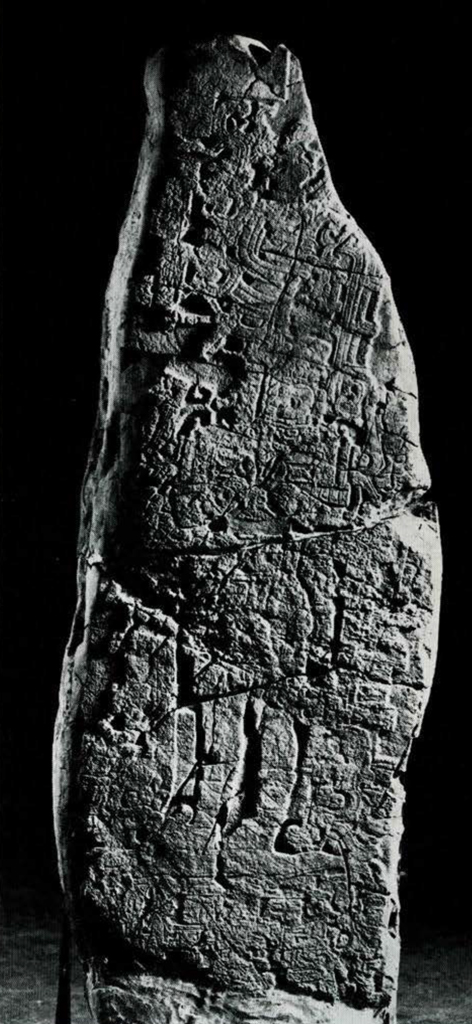

As the illustrations show, it is quite evident that the Caracol quarrymen and stone-cutters often failed to produce the symmetrical forms presumably aimed at, nor were the surfaces destined for relief carving everywhere worked down to proper flatness. It is interesting to note that on the early Stela 16 highly skilled artists had to adapt their designs to the irregularities of a very poor blank (Fig. 17); three generations later there was great improvement (Stelae 6 and 5, Figs. 10 and 8); but with the late Stela 17 standards for stone-cutters and sculptors alike seem to have been low (Fig. 19).

Museum Object Number: 51-54-8

Image Number: 51150

THE CARVED DESIGNS

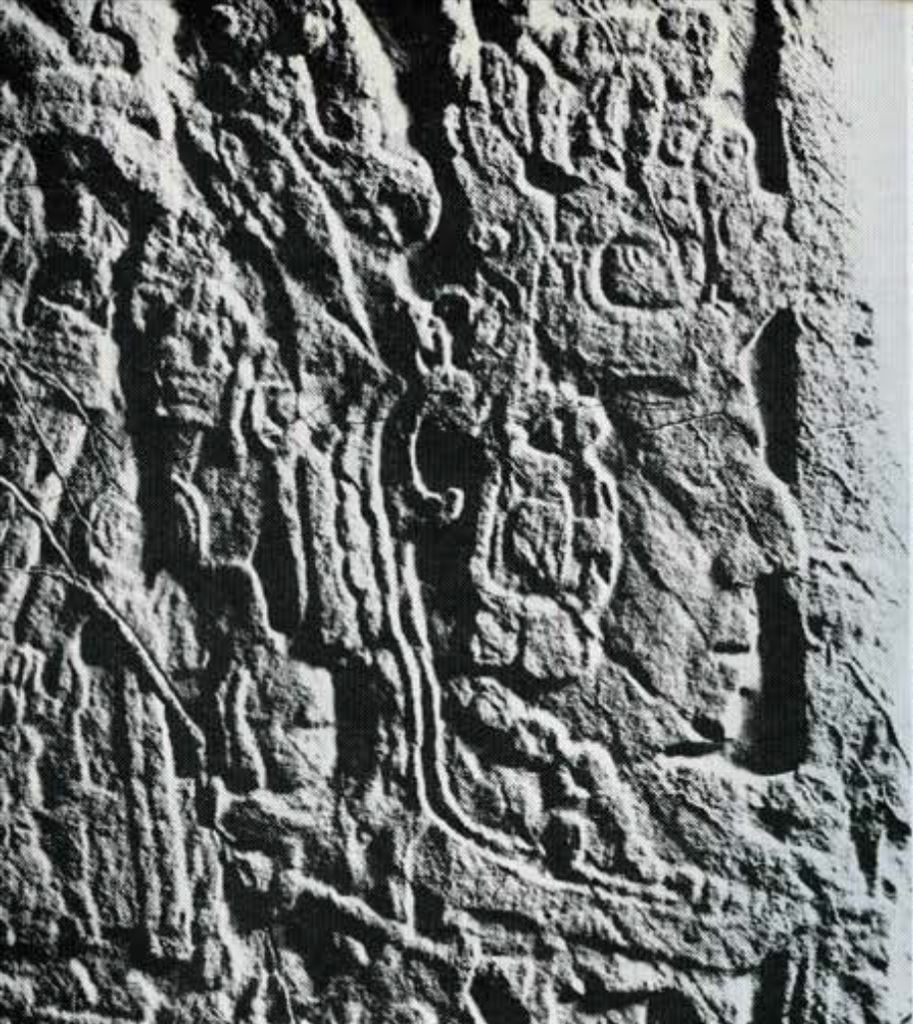

Like the great buildings with which they were associated, the monuments were products of a ruling priesthood. Basically similar designs may be found again and again as one passes from monument to monument. Very often a relief design was dominated by the picture of a standing priest wearing a great headdress and all manner of symbolic ornament. Though he appears to be perfectly human it is clear that he serves a god, or gods, perhaps impersonates one of them. On the front of Stela 16 we see such a priest, who stands alone on the mask of a grotesque deity (Figs. 18 and 19). The god-mask is hard to make out, not only because of erosion, but because three priests are shown at small scale, seated before it on this lower level, and thus most of the ugly deity is hidden. He is also hard to recognize because small hieroglyphic profile heads have been inserted in his great staring eyes. The priest himself holds a “ceremonial bar,” level and not far below his chin.

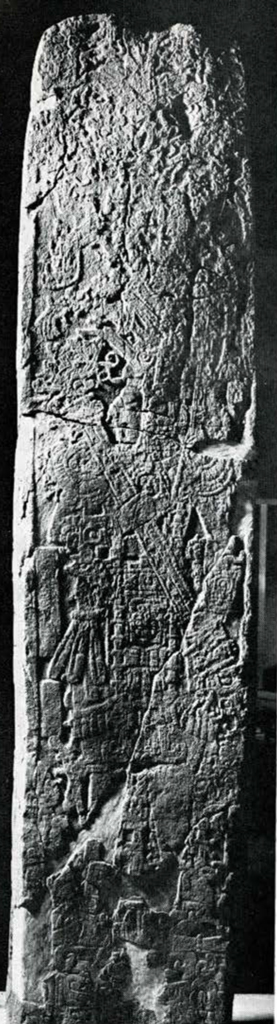

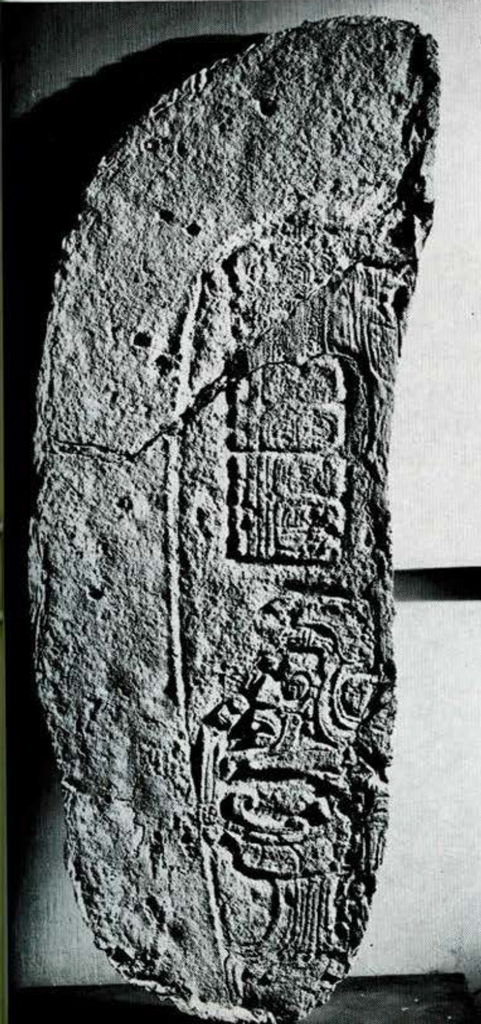

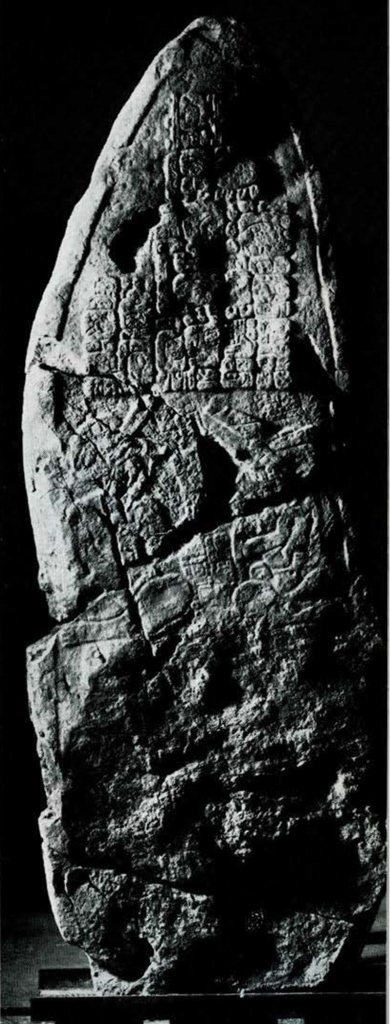

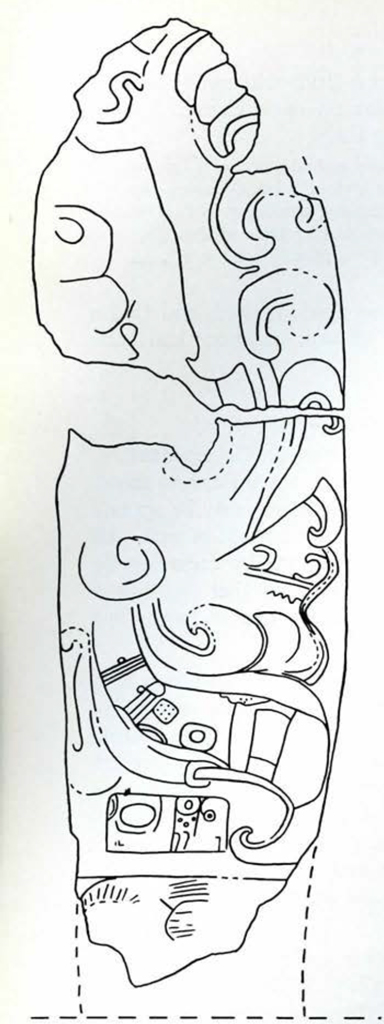

This typical sacred object, held in same position, shows to better advantage on another monument, Stela 5 (Fig. 8). Here it is clearer that each end consists of dragon-like snake heads. At each side of the stone, from their widely opened jaws, the placid faces of perfectly human-looking gods look calmly out (Fig. 5). On this Stela 5, before some loss by erosion, there were no less than ten human profile faces, besides those of the chief personage himself, and of two little men who looked up at him (Fig. 8). The pint-sized figure at the lower left is largely destroyed; the one on the right, a dwarf, holds out another sort of sacred wand, the “manikin scepter.” He may be compared with the better-preserved dwarf on Stela 1, now at Belize, illustrated in the 1951 article.

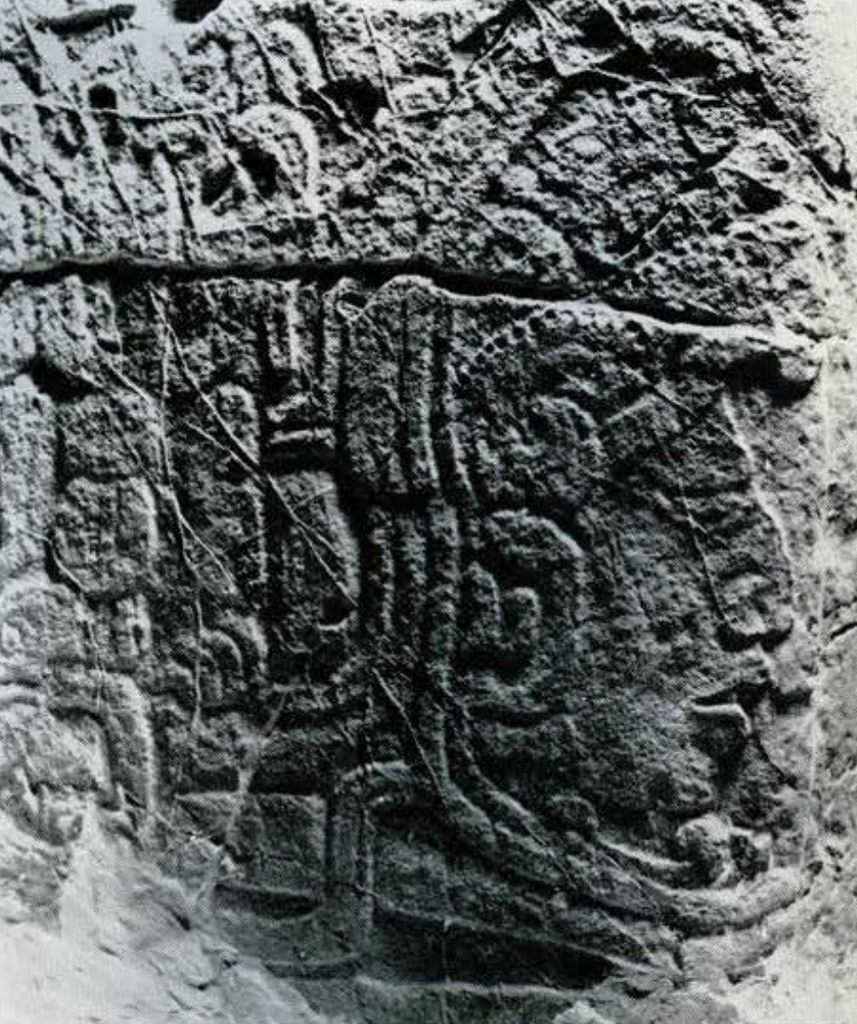

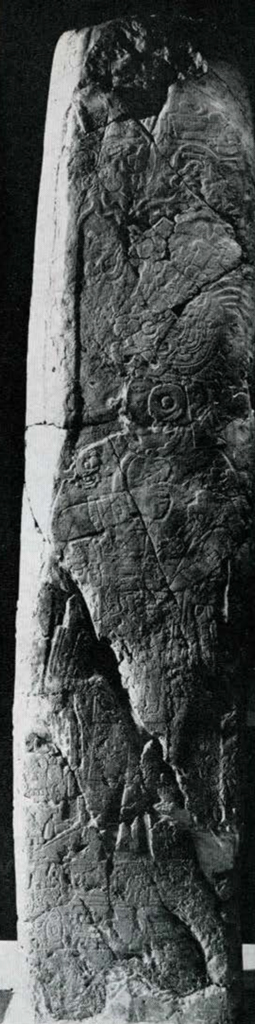

On both back and front of still another stone, Stela 6, we have again the familiar pattern-a priest standing on a deity mask. The human figure on the front (Fig. 10) carries the two-headed snake, but this time at an angle. On the back of the monument another priest is shown (Fig. 11). On his left arm he cradles something similar to, but different from, a ceremonial bar, and his right hand grasps a many-pointed object which somewhat resembles an “eccentric flint” such as we find buried in ceremonial caches under monuments and floors of buildings.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-2

Museum Object Number: 51-54-2

Museum Object Number: 51-54-2

In the field at Caracol Stela 5 became known as “the stone of the profile human heads,” three of which are shown on this page. There were thirteen in all-live with completely or partially shown bodies, and six between wide open jaws of dragon-like serpents. The complete design is shown on the opposite page.

Stela 17, and Altars 10, 12 and 13 are believed to be much later than any of the above. On these we are doubtless still being shown priests at work, but there is now no obvious indication that some single one out-ranks all others shown. On Stela 17, as on Altar 12, there are two seated human figures facing each other (Figs. 19 and 36). If the one on the left of the stela is slightly larger, this is clearly nothing but careless draftsmanship. On the altar each priest sits on the glyph-like head of a grotesque god. On Altar 13 damage makes it difficult to see that a central figure is on his knees, in profile, below a feather-wand held by the standing figure behind him (Fig. 27). But this standing figure, on the observer’s left, is at the same scale as that on the right. The latter raises his right forearm and hand before his chest in a common ceremonial gesture.

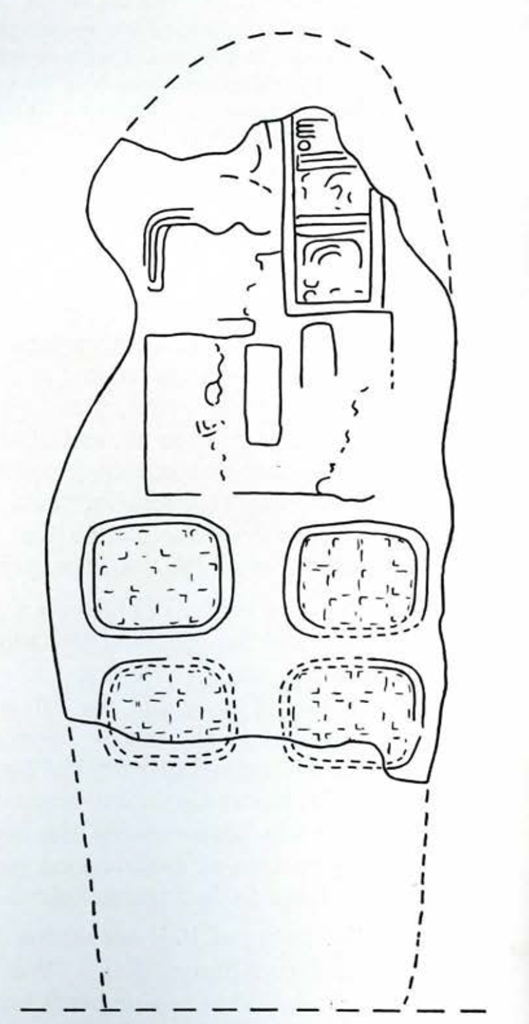

Such designs as the above were expectable in the Classical region, and are typical at the site. There are, however, a few unexpected variants among the Caracol stelae, and Figs. 25 and 26 are presented to show that departures from tradition were tolerated on occasion. Fig. 26 is nothing but a hasty sketch, but Fig. 25 was drawn to scale by Willcox from the original. This stone, Stela 18, was discovered by him personally. It seems to depict a snake-like deity just as he was imagined, with no priest as representative in evidence. On Stela 20, in bad shape, we probably have one or two priests, but the scene is at small scale in an inset panel.

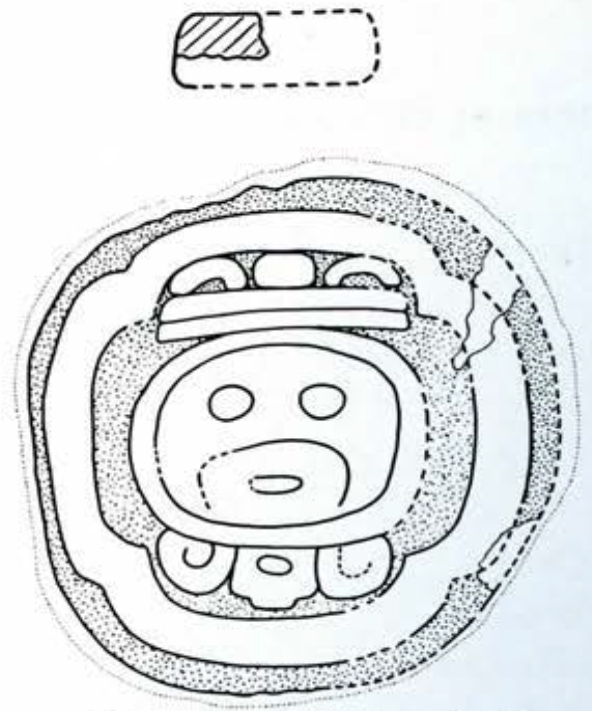

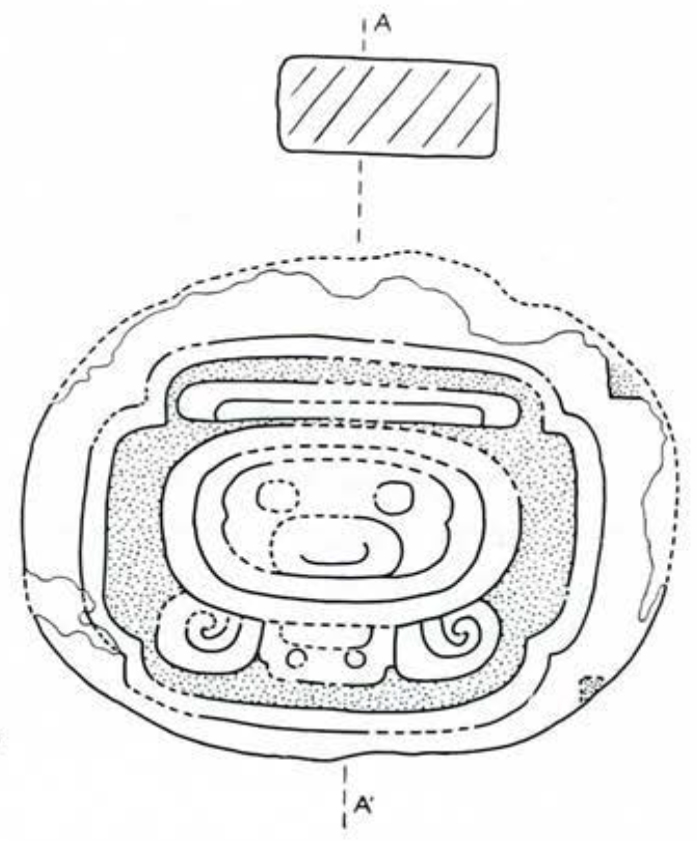

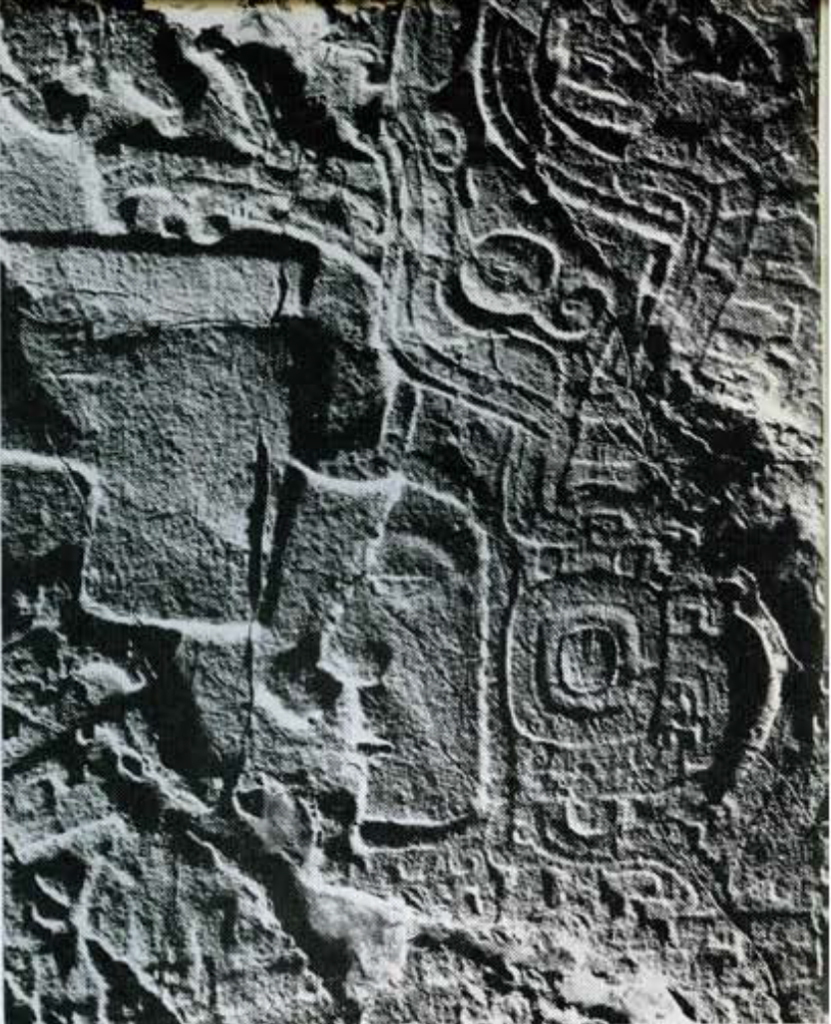

The really unique design at Caracol is the “giant glyph,” alone or with other normal-sized glyphs, on altars (Figs. 4, 32, 37-42). This, and its probable meaning, were discussed in the 1951 report. Others are now illustrated and a modification of the “katun-naming” theory for them is given later on. As noted later, the giant glyph was not confined to Caracol, but known examples elsewhere are still exceedingly rare. Here there were at least fourteen, and variations within the class can be studied.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-2

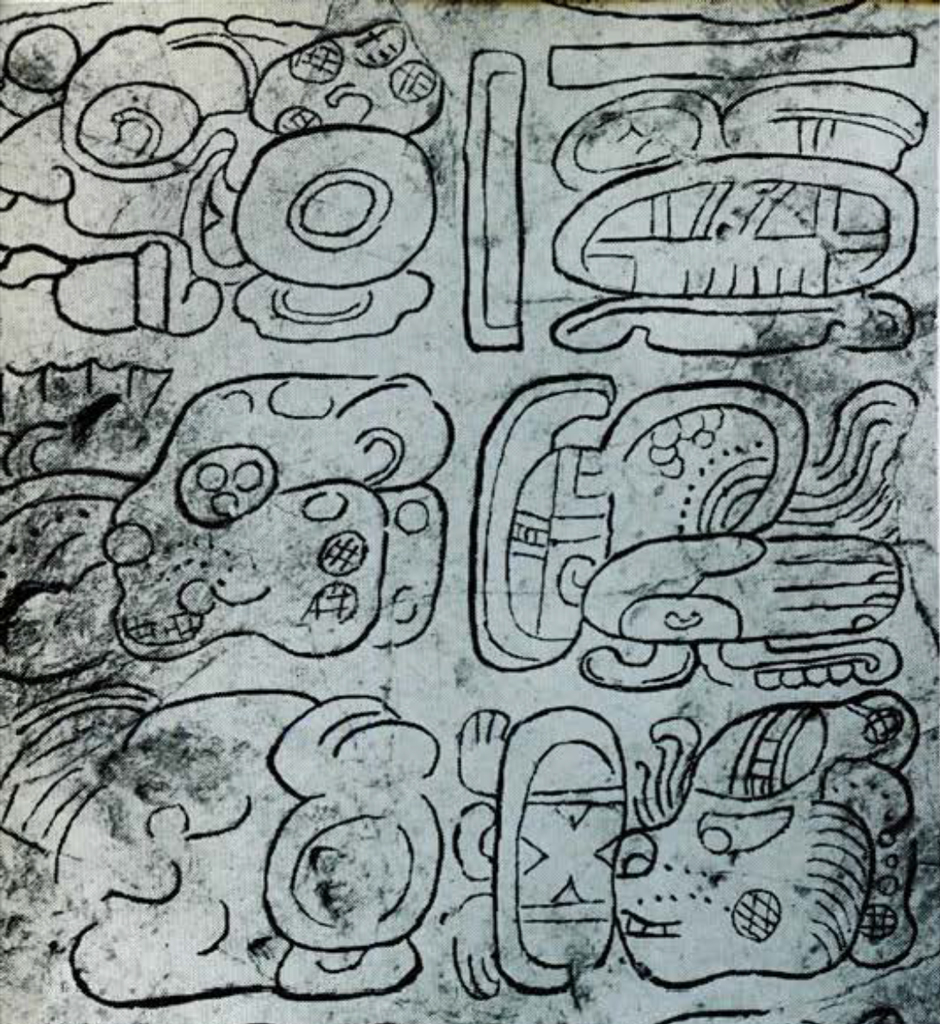

There was no scene at all on Stela 10 – just a not very long hieroglyphic inscription. This is a rare but widely distributed design which indicates that the inscriptions, which we have been ignoring so far, were important and could be read without the help of the pictures or “scenes.” Within the representational designs which are generally found, otherwise blank spaces were often filled with panels of glyphs. Even if badly eroded. raised oblong or L-shaped areas such as at the top of Stela 16, and before the priest’s face on Stela 5, are sure indicators of glyphs (Figs. 8 and 16). Such panels account for all the inscription on Stela 11, not illustrated here. On many stelae, and sometimes on altars, an area is set aside specifically for an inscription, which is arranged in “blocks” forming regular rows and columns. Such inscriptions may be on the same side as the scene. either below it, as on Stela 15, or above it, as on Stela 17 (Fig. 19), but common habits were to place the “main” inscription on the back, as on Stela 16 (Fig. 13) or on the sides, as on Stela 6 (Fig. 9).

The last-mentioned example illustrates a feature frequent at this site, but very rare if not entirely absent on stelae elsewhere. On each side the long inscription is broken up into eight segments, each in a “rounded- rectangular” frame. One wonders if the resulting spotted effect did not have a symbolic meaning. Its use seems to have extended from 9.8.10.0.0 to 10.1.0.0.0 in the Maya chronology-about two and a half centuries-and the text seems to pass from frame to frame without interruption, so far as the glyphic content is concerned. The use of these frames on the front of Stela 20 contributes in large measure to its unusual effect (Fig. 26). In that one case the frames are sunk into the stone. A single frame may contain as many as twenty glypl1s (Stela 5) or as few as one glyph (Stela 17).

The three Caracol altars with pictorial “scenes” show glyph panels on the backgrounds, just as do stelae, and like them also an area devoted to glyphs only. But here this is a peripheral border or, in the case of Altar 13 only, a scalloped frame similar to non-glyphic ones common on giant glyph altars. The glyphs in such arrangements read in clockwise direction. but since “Initial Series” are not given it is impossible to say just where these “circular” inscriptions begin and end (Figs. 27 and 36).

Museum Object Number: 51-54-3

Image Number: 51132

Individual glyph-blocks may be studied as miniature works of art. We are fortunate, I think, in having a good sample of incised glyphs for comparison with the more usual relief style (Figs. 12 and 22). The incised forms tend to be more cursive and are probably closer to those painted in now lost paper-manuscripts. Not many incised inscriptions at other sites are available for comparison, for they are difficult to photograph in the field. We hope to add to the Caracol collection of them with casts from molds of Stelae 13 and 14. I think Stela 16 may record one of the earliest incised inscriptions known. A master of calligraphic art was required to work on an extremely uneven surface, just as it came from the quarry. Because of this poor base surface, lighting under museum conditions is very difficult. Though there is no evidence that the Maya did so, the incised lines have been emphasized with water color by the writer. An effort has been made not to restore lines now worn away, and the paint can be removed from the stone at any time. Photographs of the glyphs before it was applied are available.

THE CONTENT OF THE INSCRIPTIONS

What the glyphs say is of paramount importance, and those who are interested in Maya archaeology soon become aware that these inscriptions involve dates recorded in the Maya system. Often there are several dates in a single inscription, with the record of the number of days between them, and the number of clays between one of them and a common starting point or epoch far in the past. The latter are called “Initial Series” or “Long Count” numbers. Usually, if erosion is not too far advanced, by reasoning from patterns established on many known monuments, some one elate on a new monument-and its position in the “Long Count”-can be picked out as being approximately contemporaneous with the carving of the stone, and it is called the “commemorative” or the “dedicatory” date. It is these Long Count positions for these dates only which arc listed in Table 2.

It is not so clear what various “non-calendrical” glyphs are saying about the dates between which they appear, but much solid progress has recently been recorded by J. Eric S. Thompson, of Carnegie Institution of Washington (Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: Introduction, 1950). His monumental work was being issued as we were discovering some of the new Caracol inscriptions, and it makes them more immediately valuable than previously. It is clearer than before that language was being more or less completely recorded, though not alphabetically. Some of the signs seem surely to be phonetic “rebuses,” mixed with pictographic and ideographic glyphs. The phonetic elements suggest that the inventors of the script spoke a lowland Maya language akin to present-day Yucatec or Chol. According to Thompson they were striving for a “euphonious grandeur” in what they chose to record on stone.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-3

Museum Object Number: 51-54-3

In the field at Caracol Stela 5 became known as “the stone of the profile human heads,” three of which are shown on this page. There were thirteen in all-live with completely or partially shown bodies, and six between wide open jaws of dragon-like serpents. The complete design is shown on the opposite page.[/caption]

Names of gods appear, but not those of human beings or places. The texts seem to have poetic overtones and not to be historical statements in any ordinary sense. Why then the emphasis on dates? The answer presumably lies in the well-established fact that Middle Americans generally foretold the future by means of a system of calendrical divination. Whether dealing with the affairs of individuals, the community, or “the world,” one might say that Time was the Supreme Power, and experts calculated its effects, reasoning from the past across the present to the future. At the heart of the system was a belief that many gods existed, good and bad, but that their powers waxed and waned cyclically in time. A combination of supernatural powers ruling today would be supplanted by another set reigning over tomorrow. A group of gods dominant this year would yield to another next year. Time, as Thompson shows, was forever laying down one “burden” of fortune, and picking up the next in a series. The fates changed each day and each year until, after specific numbers of days and of years had passed, the respective series of changing fortunes repeated themselves – and so without end.

One of the specifically Maya elaborations of this wide-spread concept was a cycle of 13 katuns, with changing prognostications at the end of each katun. Since each katun lasted through 20 approximate years called tuns, a given set of katun prophecies was turned up by the wheel of time every 260 years. (By “year” we understand here the Maya tun of 360 days, and not the 365-day year which they shared with other Middle Americans.) If such time-cycles governing fate appear to have been entirely artificial creations, real astronomical cycles also had to be reckoned with. Doubtless for this reason we are told on Stela 16 that, at the end of a stated katun, the moon was seven days old.

It is certain that most Maya monuments were dedicated at the ends of katuns, or at the ends of first, second or third quarters of these 7200-day periods. A quotation from Thompson’s new study will summarize the best opinion on the nature of the inscriptions on our stelae and altars, and the reason for the periodicity in carving them.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-3

“I further believe that the calculations they made to find precedents for the various combinations which would influence the end of a katun occupy the bulk of the inscriptions. That is to say, they were using astronomy to develop laws of astrology, and combining the results with what they knew of the direct influence of the days themselves. It was a scientific approach, but the original premises were false.”

There is no doubt whatever that calculations were involved, and that a special arithmetic, with place-value notation of large numbers, had been invented for the purpose in Middle America.

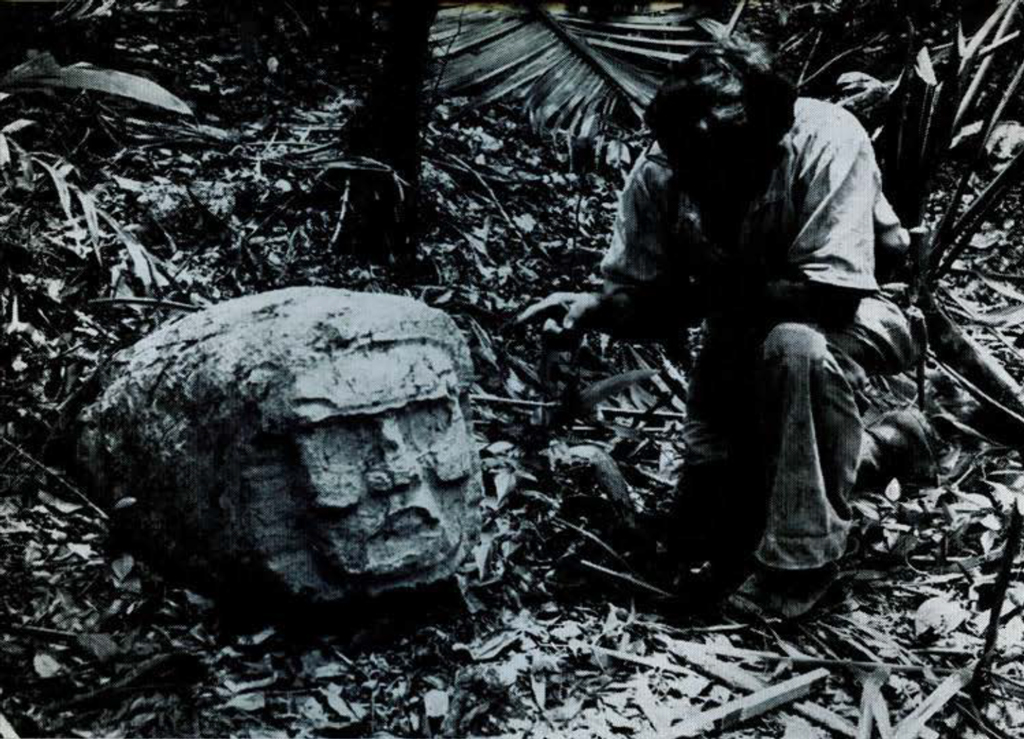

FIELD SEASONS Of 195l AND 1953

A. Hamilton Anderson, representing the Colonial Government of British Honduras, took us to the site in 1950. He was present so much of the time, and so active, that “joint expedition” might fairly be applied to the work of this season, and of the 1951 and 1953 seasons as well. All monuments brought out from the site were discovered by these expeditions, with the exception of Stela 1. Anderson found that and left it partly buried in 1938. Before that year Caracol was one of those “lost Maya cities” of which romantic writers are so fond.

At the close of the 1950 season we made preliminary arrangements with Anderson and his governmental superiors looking to removal of some of the better preserved sculptures. His excellency the Governor, Sir Ronald Garvey, Lady Garvey and the Private Secretary, Major C. V. C. Herbert, had come out to the site to inspect the new finds. An informal understanding was arrived at with His Excellency and with the Colonial Secretary, E . D. Hone, Esq. Arrangements were also made with Mr. Louis M. Sylvestre, who was working the region for mahogany logs, for loading thirty gross tons of crated monument material on his trailer trucks and carrying them to the capital, Belize.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-5

Image Number: 51133

In the spring of 1951 we returned for further exploration, equipped to move and pack heavy stones. We had to allow for rough handling by men accustomed to tossing heavy logs about. The Department of Anthropology of this University had been drawn on for two archaeological assistants, Horace Willcox and Seymour Nuddle. By systematic searching these two energetic friendly rivals added substantially to the list of known monuments, and four of the 1951 finds are among those brought out. Most of them were found at some distance from those previously known. We now distinguish two principal monument-bearing areas of ceremonial architecture as Group A and Group B, and two minor ones as Group C and Group D. Once the period of further search was declared ended the choices of what should be removed were made, and we began a race with time to get ready for Mr. Sylvestre’s bush transportation experts. When they should arrive there could be no delay, for the rains would be starting.

Many difficulties arose-chiefly in matters of supply, and in failure to find a local man, skilled in moving heavy objects, who would join our crew as foreman. We all had to devote much time to practical problems, teaching ourselves first, and then, as somewhat half-baked masters, teaching unskilled workmen. Eventually the load was somewhat lightened by obtaining the services of a proper carpenter, but much of his time went into producing timbers from the forest. Normal archaeology had to take second place, and nearly all digging was in the vicinity of stones marked for export.

A beginning at the preparation of a proper site map was made by Nuddle, but it could not be completed, and many monuments, left at the site, could not be fully recorded. In the spring of 1953 I went back with Jeremiah F. Epstein as student assistant for a final “wind-up” season. He finished the mapping and I devoted myself principally to monuments. It is impossible to work at such a site without discovering something unexpected, and Epstein began it by spotting a vaulted tomb, in perfect condition. One of my men duplicated this with another, smaller, in not such good condition, but with more whole pots. Excavation of these was put off until the rains should stop us elsewhere. By that time Epstein was on the point of leaving, according to schedule. Anderson had come out to pay us a long visit and he excavated both of them for us (Figs. 28 and 29).

This final season added somewhat to the list of sculptured stones. One of these was a very unexpected find. It is the bottom half of Stela 3, found lying on the surface in Group B, whereas the top half had been found in 1951, erect and a quarter of a mile away, in Group A. This seems to clinch the argument that, in ancient times, monuments which had been set up were thereafter broken and moved considerable distances. We had already brought the top half to Philadelphia. Though not prepared for such work this year, having sought permission, we got it crated and out to Belize. As recounted later on, the complete monument is now at Denver.

It may be added that on the way down in 1953 we left Philadelphia a month early, before the weather would have permitted operations at Caracol. This month was spent with Dr. Gordon Willey of Harvard and his student assistant, Mr. William R. Bullard. We stopped off in Yucatan, spending two instructive days at Mayapan as guests of Dr. Harry H. D. Pollock and the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Thereafter we were in the Colony, most of the time looking over the archaeological situation near El Cayo, with a view to future work there by Dr. Willey. Deciding favorably, he took over our jeep and camp equipment when we were through with them at the end of the 1953 season.

CHECKLIST OF CARACOL MONUMENTS, WITH LOCATIONS

| (A) Stelae, and Altars Surely Associated with Stelae | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| St. 1 | Grp. A | Belize | |

| Alt. 1 | ” A | Belize | (GG) |

| St. 2 | ” A | ||

| St. 3 | ” A, B** | Denver | |

| St. 4 | A** | Phila. | (slate) |

| St. 5 | ” A | Phila. | |

| St. 6 | ” A | Phila. | |

| St. 7 | ” A | ||

| St. 8 | ” A | ||

| St. 9 | ” A | ||

| Alt. 4 | ” A | (GG) | |

| St. 10 | ” A | ||

| St. 11 | ” A | ||

| Alt. 19 | ” A | (GG) | |

| St. 12 | ” A | (plain) | |

| St. 13 | A “ | ||

| St. 14 | A “ | ||

| Alt. 7 | ” A | Phila. | (GG) |

| St. 15 | ” A** | Phila. | (slate) |

| St. 16 | ” A** | Phila. | |

| St. 17 | ” C | Phila. | |

| Alt. 10 | ” C | Phila. | (scene) |

| St. 18 | ” B | ||

| St. 19 | ” B | ||

| St. 20 | ” A | ||

| St. “X” | ” A | (slate) | |

| Alt. 3 | ” A | (GG) | |

| (B) Altars Not before Stelae When Found | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alt. 2 | Grp. A | (GG) | |

| Alt. 5 | ” A* | (GG) | |

| Alt. 6 | ” A | (GG) | |

| Alt. 8 | ” A | (plain) | |

| Alt. 9 | ” A | (plain) | |

| Alt. 11 | ” B | (GG) | |

| Alt. 12 | ” B** | Belize | (scene) |

| Alt. 13 | ” B | Phila. | (scene) |

| Alt. 14 | ” A | (GG) | |

| Alt. 15 | ” A** | (GG) | |

| Alt. 16 | ” B* | (GG) | |

| Alt. 17 | ” A* | (GG) | |

| Alt. 18 | ” B* | (GG?) | |

| (C) Unclassified Monuments, Fragments and Groups of Fragments | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stone 27 | Grp. A | (plain) | |

| Stone 28 | ” A* | Belize | |

| Stone 29 | ” A* | (plain) | |

| Stone 43 | ” B | (plain) | |

| Stone-Group 46 | ” A** | Phila. | (slate) |

| Stone-Group 48 | ” A** | Phila. | (slate) |

| Stone-Group 50 | ” A** | Phila. | (slate) |

| Stone 55 | ” D | ||

| Stone 56 | ” A** | Phila. | (slate) |

| Stone 58 | ” A** | (plain) | |

| Stone 60 | ” C** | Phila. | |

All known Caracol monument material is set out in Table 1. Full description must await final publication, so it is necessary to point out that existence of a stela or altar number does not mean necessarily that the whole, or even much, of the monument has been found, or that carving survives on all of what has been found. Quantitatively the list is a better index of what once was than of what now is.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-7

Museum Object Number: 51-54-5

If an asterisk is added to the letter showing the mound group in which the item was found, there was evidence of disturbance. One asterisk means that this may have been only natural disturbance involving considerable movement; two asterisks indicate apparent disturbance by human action. In these cases it would be especially risky to conclude that the monument never was a member of a stela-altar pair, merely because positive evidence for it is lacking.

A given monument was left in the mound group indicated in the table unless the city where it may now be found is given in the next column. “CG” in parentheses identifies an altar as of the “giant glyph” class, rather than of the “scene” class. All items are carved unless labeled “plain,” and are of limestone unless stated to be of “slate.”

“Stela X” may possibly be a part of either Stela 4 or 15, both of which are also of slate. Until this can be disproved the makeshift designation avoids carrying the stela numeration beyond what is surely a correct minimum. In all probability there was at least one more stela, and who knows how many may be missing from our list because broken up and buried or scattered in ancient times? “Stone” and “Stone Group” numbers are according to an original identification series, retained for a given item until it can be classified.

Stones 28 and 29 may possibly have been architectural elements rather than monuments in the true sense. Nineteen of the twenty sure stelae were carved, as were seventeen of the nineteen altars. The high count of carved altars is due, however, to the local giant glyph idea, fourteen being of this class.

The monuments at Belize will soon be on exhibit in a new fireproof building of the Baron Bliss Institute; Stela 3 will be on view at Denver Museum of Natural History. Our monuments are on exhibition in our Middle American Hall, except for the very incomplete Stela 4 and other fragmentary slate material, which are in basement storage.

DETERMINING THE GOVERNMENT AND MUSEUM SHARES

The present locations of monuments taken from the site result from a division between the Colonial Government and ourselves, made on the spot in 1951, before the boxing and crating. If a division of archaeological finds on Crown lands is permitted at all, the law and regulations provide for a share-and-share alike division. It is decided by lot that one or the other party shall have first choice; thereafter each chooses alternately until the collection is exhausted.

Mr. Anderson, representing the Colonial Secretary, came out to apply the rule to a rather mixed lot of material. We decided together what ought to be brought out, within our tonnage limitation, and soon came to the conclusion that a mutually more satisfactory result would ensue if some of the units of choice should consist of several numbered items. The general idea was that the first and second choices should dispose of equal amounts of “value,” so far as that might be possible, and so with the third and fourth choices, and so on. So we balanced certain obviously preferred single items against groups of individually less desirable ones. After the toss, which went to the Government, we chose from among a series of single items and groups of items.

In forming the groups, the original beauty of the design was important, but differential erosion of what may once have been equally desirable monuments was considered, as was the frequent factor of completely missing portions. The degree of fragmentation also affected desirability, for extensive fragmentation meant time and expense for restoration, with a very imperfect notion of how effective the final result would be. All of the slate material was thrown into one group because its exhibition value was next to nothing and it required study as a whole before its significance could be determined.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-5

Image Number: 51133

Museum Object Number: 51-54-5

The Government for some time will have restricted storage and exhibition space and no ready-trained restorer at hand, and it chose three of the four available complete and unbroken items. We tended to choose from among the groups of fragments yielding a greater quantity of numbered items, relying on our ability to even things up later by restoration.

Each collection is fairly representative. In each, one may see the typical more or less life-size priest with ceremonial bar, attended by a dwarf; in each, giant-glyph as well as “scene” altars are represented; in each there is a stela-altar pair, and incised as well as relief inscriptions.

In this division we received the top half of Stela 3, shown in the table as now at Denver. It did not rate high because of incompleteness and also extensive erosion. It was included in a sale of casts of Piedras Negras material to Denver Museum of Natural History, the proceeds of which have been applied to restoring the Caracol pieces which remain here. When the much better preserved bottom half of Stela 3 was found in 1953, it was apparent that if it could be joined to the top, a very worthwhile result would ensue. After obtaining permission, we crated it and got it to Belize, as already noted, without knowing just what disposition would be made of it. Eventually, His Excellency, P. M. Renison Esq., at this time Governor of the Colony, presented the lower half to the Denver institution as a goodwill gift to the people of Denver. The Denver Museum has reimbursed us for all extra costs involved.

DEDICATORY DATES IN THE MAYA LONG COUNT SYSTEM

The rest of this paper proceeds on the assumption that the reader is familiar with the Maya “Long Count” and “Short Count” methods of dating, at least to the extent provided for in the 1951 discussion of the probable meaning of the “giant-glyph” altars. What follows anticipates fuller presentation in a final study, and most of it is selected as having a direct or indirect bearing on the theory that the enormous glyphs on such altars referred to particular katuns of the “Short Count.” With more data now available the announced theory seems to require minor revision.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-6

Table 2 summarizes, with some cautionary question-marks, what it now seems safe to say about dedicatory dates as indicated by ordinary inscriptions (A), and by giant-glyph altars (B). There are some disagreements with a shorter and differently arranged table of the prior report. In 1952 Anderson’s sharp eyes proved that we had both been mistaken in thinking that Stela 14 was unsculptured, and that the back of Stela 16 was plain. The clear dedicatory Initial Series elate 9.5.0.0.0 11 Ahau on the latter limestone stela makes it unlikely that that was the elate of “Stela X,” and hence of its 11 Ahau altar (Altar 3), as we had supposed. One does not expect two stelae, of different materials at that, to be dedicated together at so early a date, and at so comparatively small a site. Whether another since-discovered 11 Ahau altar, Altar 14, once belonged with Stela 5 at 9.5.0.0.0 had best be left undetermined. I was blamably at fault in listing Altar 6 as recording 9 Ahau. Fitting fragments found since show dearly that the statement was 7 Ahau (Fig. 37).

Table 2. Maya Dates

| (A) Normal Inscriptions-Probable Dedicatory Dates | ||

|---|---|---|

| St. 15 After | 9.4.16.13.3 | (I.S. reconstructed) |

| St. 16 At | 9. 5. 0. 0. 0 | (I.S.) |

| St. 14 At or after | 9.6.0.0.0 | (I.S. incomplete) |

| St. 1 At | 9.8.0.0.0 | (I.S.) |

| St. 6 At | 9.8.10.0.0? | (CR, probable “half period”) |

| St. 5 At | 9.9.0.0.0? | (CR) |

| St. 3 At | 9.9.10.0.0? | (CR, “half period”) |

| St. 19 At | 9.19.10.0.0? | (CR) |

| Alt. 12 At | 9.19.10.0.0? | (CR, probable “half period”)* |

| Alt. 13 At or after | 9.19.10.0.0?? | (CR)* |

| St. 17 At | 1O.1.0.0.0? | (CR) |

| * Eroded day-sign restored as Ahau. | ||

| (B) Giant Glyphs with Fully Legible Day-numbers – Katuns Probably Referred to as Current or Ended | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alt. 4 | 2 Ahau* | 9.3.0.0.0 or 9.16.0.0.0 | (with St. 9) |

| Alt. 3 | 11 Ahau | 9.5.0.0.0 or 9.18.0.0.0 | (with St. X) |

| Alt. 14 | 11 (Ahau) | 9.5.0.0.0 or 9.18.0.0.0 | |

| Alt. 6 | 7 Ahau | 9.7.0.0.0 or 10.0.0.0.0 | |

| Alt. 16 | 7 (Ahau) | 9.7.0.0.0 or 10.0.0.0.0 | |

| Alt. 1 | 5 Ahau* | 9.8.0.0.0 | (with St. 1 |

| Alt. 19 | 1 Ahu* | 9.10.0.0.0 or 10.3.0.0.0 | (with St. 11) |

| *”Notched” form of normal Ahau face, making earlier alternative Long Count position more probable; Altar 1 dated by its stela. | |||

On this page (figures 20-23) are samples of Caracol hieroglyphs believed to include dedicatory dates of five stelae. Incised and relief styles of depiction are used.

Another change on the level of supposed facts must be noted. Altar 7 was read as recording 7 Ahau, but is now shifted to the group of doubtful giant day-number readings. Mr. Thompson, examining the original on our floor, was the first to note that a combination of faults in the stone and subsequent erosion may have tricked us into seeing only one decorated bar where two had actually been present. The “preferred” reading is 12 Ahau rather than 7 Ahau-and surely one or the other is correct. For the original 7 Ahau reading the alternative Long Count positions in Table 2 would be 9.7.0.0.0 and 10.0.0.0.0; for the 12 Ahau reading they would be 9.11.0.0.0 and 10.4.0.0.0. Either late alternative is improbable because of the “notched” style of the Ahau face, and also because the katun of the Initial Series on the associated Stela 14 was certainly no higher than 9.

When casts are made from molds of eroded portions of this stela, and of Stelae 11 and 20, we may have more glyphic material to deal with; also, satisfactory photographs of the Initial Series of Stelae 1 and 3 are yet to be obtained, though many variant lightings were tried in the field.

However, there is no question about the Stela 1 reading, and the “Period End” date listed for Stela 3 certainly appears on it (Fig. 24). We now have a highly objective system of dating within limits by the style in which the human figure and associated objects are drawn (A Study of Classic Maya Sculpture by Tatiana Proskouriakoff, Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1950). Where it can be applied to the stelae this will, I think, confirm the suggested dedicatory dates; conversely, the dates having been discovered since the method was formulated, they tend to confirm its validity.

The “normal inscriptions” (A in the table) indicate local monument-carving from fairly early to really late Classic times-a span of time within which a katun of a given “name” turned up twice, though not three times. So, if a given Caracol altar gives us a katun name, and that is all we know, the katun may have been at either of two Long Count positions. These two possibilities are given in the table (B), except in the case of Altar 1. There we know more – its stela is legible and dates both stones at 9.8.0.0.0, rather than 13 katuns later, at 10.1.0.0.0.

Three entries are starred to indicate that their Ahau faces are of a special “notched” variety which, in ordinary inscriptions, is supposed to have gone out of style in the central region long before 9.16.0.0.0. It is highly probable therefore, that Altars 4 and 19 refer respectively to katuns at 9.3.0.0.0, and 9.10.0.0.0, and not to katuns at the later Long Count positions given at the right as possibilities. It seems best, however, even in these cases, to keep all theoretical possibilities in the picture pending thorough analysis of local as well as general glyphic and other traits which might have chronological implications.

It was supposed at first that mere size not only guaranteed that a giant-glyph altar referred to a particular katun by giving its ending-day “name,” but also that the altar was dedicated at this time, and thus was always a “katun marker” like Altar 1. There are now reasons, noted below, for modifying the theory, and stating it thus: A giant glyph referred to a particular katun; this katun may be presumed to have been current as of the dedicatory date of the monument or to have ended on that elate; in rare instances the katun referred to may have ended shortly before a “non-tun-ending” dedicatory date.

The upper part of our table (A) suggests a local habit of marking half as well as whole, completed, katuns, so that two giant-glyph altars might well have referred to a single katun, only one of them being a “katun marker,” the other being a “half-katun marker.” The modified interpretation is in line with and really required by some evidence just published in Thompson’s great work, which I missed before. He cites several inscriptions which carry “katun-naming” well back in Classical times. I will illustrate with his earliest example, on Stela 1, Tulum. This is believed to have commemorated the mid-point of a katun, at 9.6.10.0.0 8 Ahau. The “half-period” glyph is therefore appropriate and is given, followed by 7 Ahau, the latter interpreted by Thompson as “the day on which the current katun ends.” In the terminology used here it was the “name” of the current katun which would end at 9.7.0.0.0 7 Ahau. Had this 7 Ahau at Tulum been given at giant size on an altar before the stela, the situation would have been precisely what we postulate for Caracol. We may regard the giant size as merely giving great emphasis to one portion of a date-stating pattern already established in “normal” inscriptions at other sites.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-3

If we now have the correct view as to the meaning of the giant glyphs, and since ambiguity in Maya chronological matters was seldom tolerated, we must suppose that the precise dedicatory date was recorded or otherwise made certain by normal-sized glyphs. This could be clone on an associated stela, if there was such, as on Stela 1, served by Altar l; otherwise one would expect date-fixing normal glyphs on the giant-glyph altars themselves. Normal-sized glyphs occur on several supposedly independent Caracol altars, along with the giant glyphs, but they are no longer legible. Altar 14 is interesting in this connection. Though there were no proper panels of normal-sized glyphs, and apparently no associated stela, glyphs seem to have been inserted in the three supporting elements of the “pedestal” of the giant day-sign. One can only say now that the left glyph probably had a “coefficient” of 10 to 19 (Fig. 40). This seems good (but not conclusive) evidence that this giant glyph, at ]east, did not comprise the complete chronological statement. If the recorded coefficient was 11 or 18, this would be consistent with the notion that here it was once told whether this giant glyph referred to the Katun 11 Ahau at 9.5.0.0.0 or to the next one at 9.18.0.0.0, and whether the katun was completed or not.

However, a number of giant-glyph altars were found, apparently undisturbed, not before stelae to which they must have belonged, and definitely without extra glyphs on the altars themselves. Thus the case for the katun-naming hypothesis is less water-tight than one would desire. It is possible that where a giant-glyph altar was surely chronologically ambiguous unless more information was given on a now unknown stela, such a stela was nevertheless once served by it. We have the instructive example of “Stela X,” all but a small part of the butt of which was removed from behind the other giant 11 Ahau altar. This, Altar 3, had no other glyphs (Fig. 39).

The possibility of now lost stela-altar associations thus becomes pertinent to the giant-glyph problem. One would have thought that altar size, and perhaps form, might give some control in speculations along this line. The data are summarized below and applied to known stela-altar associations. It does not seem to interfere with the theory that if a giant-glyph altar did not speak clearly for itself, it served a stela which did so.

On Altars 14 and 16 the areas within the day-sign cartouches are hopelessly eroded, and Ahau is restored for them in Table 2, as required by the katun-naming hypothesis. Remnants of the designs within two rectangular giant-glyph altars, excluded from that table because of doubtful day-numbers, show that the “normal” Ahau face with round eyes was not present, but they suggest the possibility of a well-known alternative form, a profile face (Fig. 32). Any evidence that only Ahau – in one form or the other – could appear at giant size would be welcome, but we probably are not mistaken in presuming that this was the case.

Thompson sends me two unpublished photographs showing that the giant-glyph idea was not confined to Caracol-as we had thought-and that, as one would expect, the profile head could be used. These pictures show 4 Ahau and 5 Ahau at giant size at Altar de Sacrificios, a site far to the west of Caracol, on the Usumacinta river. They appear to be on fragments of stelae, rather than on altars, a circumstance which in no way militates against the katun-naming hypothesis for them. Details will presumably become available in a future report on the 1937 visit to this siteby Pollock, A. Ledyard Smith and Shook, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

A not very exhaustive search of the literature carries the trait in another direction, this time to an altar at Quirigua, far to the southeast. Again an interesting detail emerges, tending to justify restoration of Ahau in all eroded giant-glyph day-sign cartouches. On the long-known Altar L of Quirigua there is a “scene,” with normal-sized glyphs; but these are within a giant day-sign cartouche, with day-number 10 above. From the very beginning (and not merely later because of erosion), one had to understand what the day-name was, without being actually told. There would have been ambiguity unless the giant size implied some particular one of the twenty possible day-names. The evidence elsewhere is that it is the day Ahau which correlates with giant size. This is not a proper place to discuss the Quirigua altar in detail. I think a good case can be made for the proposition that it marks a Katun 10 Ahau, or else refers to this katun-end as being shortly before a dedicatory non-tun-ending date given in Calendar Round form.

Image Number: 51134

Drawings of unusual stela designs at Caracol. Figure 25 was drawn to scale from the original, by Horace Willcox.

Image Number: 51134

Drawings of unusual stela designs at Caracol. Figure 26 is a hasty field sketch with some detail added from photographs.

SIZES AND FORMS OF ALTARS

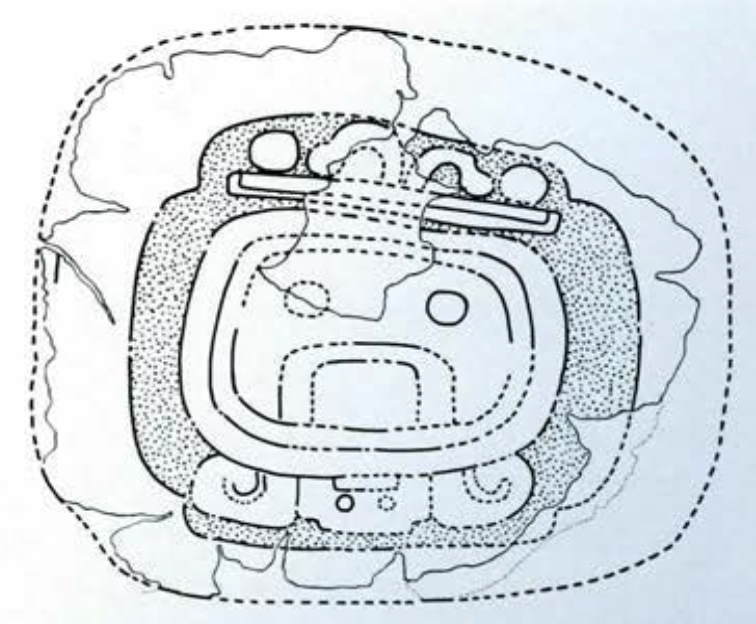

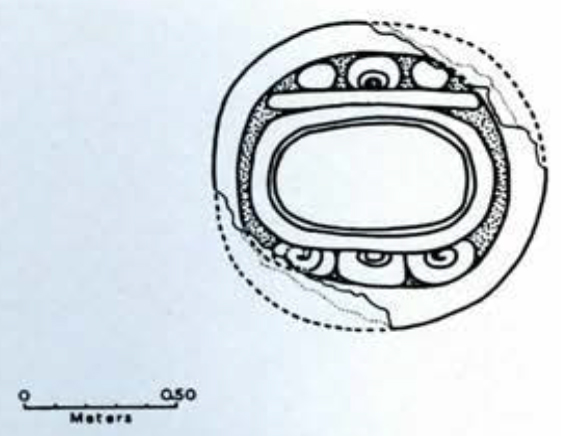

Caracol altars vary greatly in size and shape. Figures 34-35, 37-42, all at the same scale, provide a fair sample in respect to size, and to what may be called provisionally the “rounded” forms. One is bound to wonder how much of the variation is clue to chance, and whether some of it is functional or due to esthetic ideas which changed with mere passage of time.

In the drawings, heavy lines, broken where restoration is necessary, are used for the periphery at the top level, and for the design at this level, with stippling to indicate slightly sunken areas. Irregular solid light lines show where parts of the top surface are completely gone, and not merely weathered. All edges were plain; if they bulge outward beyond the periphery of the top, the resulting slightly larger periphery at a lower level is shown in dotted line, but not when the edge is approximately straight or curves inward from the top. Thus, in Figs. 37 and 41, peripheries at the tops have been restored with more control than is apparent in the drawings. Where the edge was missing at all levels, the maximum extents of the surviving portions are indicated by irregular dotted lines (Figs. 37 and 38). Despite the considerable amount of broken-line restoration which has been necessary for the peripheries of the tops, they probably reflect reality rather closely. The drawings were made carefully from the originals in daylight, with some details added from night-lighted photographs. With others not published here they yield the data of Table 3.

In this table AA’ is the longer, BB’ the shorter axis of the top. Within each grouping by class of design the tabulation proceeds downward in descending order of the longer axis, usually among altars of approximately the same size and weight, or else from larger to smaller. When a pair of axial dimensions for a single stone seem to differ insignificantly, clashes between them give notice of this fact, and “round” or “square” is used in the descriptive term for the shape; “oval” and “oblong” are used elsewhere.

Museum Object Number: 51-54-9

There are six cases in which one dimension of a carved altar was noticeably shorter than the other; in four of these the shorter axis was the vertical axis of the design; it probably was in a fifth case also (Altar 17); while in the sixth, definite evidence is lost (Altar 11). Apparently a feeling existed that if the axes differed significantly, the design should show its greatest extent laterally, not vertically.

Thus far, “rectangular” and “rounded” (rather than the usual “round”) would cover our variations in peripheral form. The addition of “irregular” or “flattened” in numerous cases requires explanation. The drawings show that many of the outlines bulge out or are pinched in from ideal true round or oval forms. Our notes refer to “dimples” where the irregularity is a pinching in, and usually here the edge was less well worked than elsewhere-fair evidence that the reverse curve of a “dimple” at least was not actually desired. Altars which show these bulges and “dimples” are classified as “irregular round” or “irregular oval.” It may be presumed that the irregularity was tolerated but was not actually desired; it does not follow necessarily that in all these cases true round or oval peripheries were aimed at. Though proof escapes one, “flattened round” may have been sought for, with “irregular flattened round” actual results.

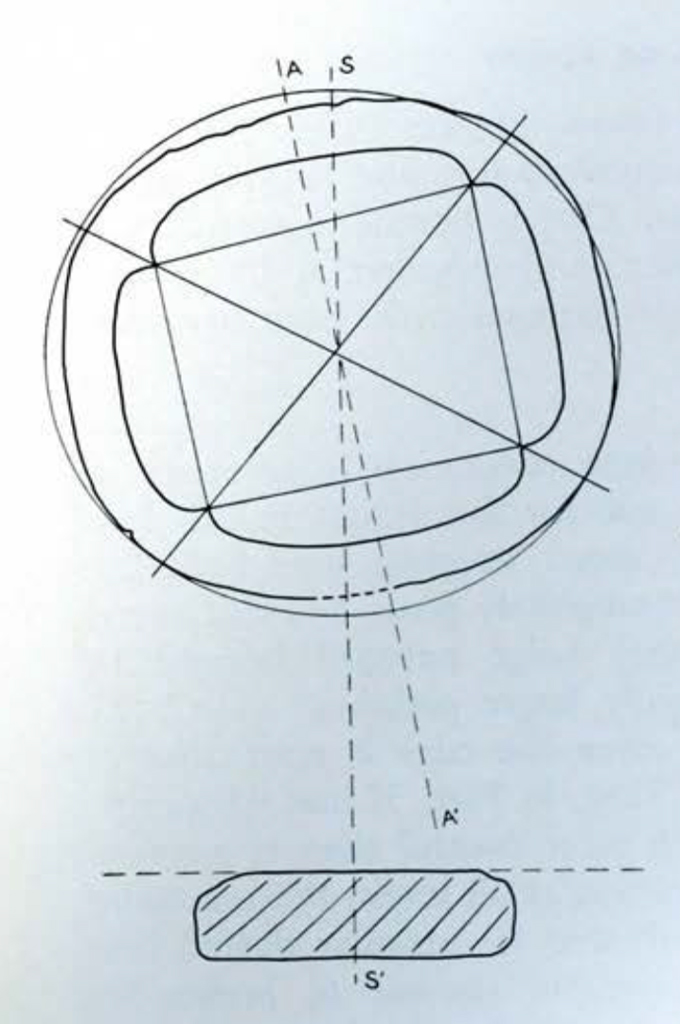

Evidence for this notion consists of two altars which show the “flattening” without the irregularity. Altar 12 is a probably late example, and Altar 19 a probably much earlier example (Figs 35 and 36). Further, it is possible to speculate on why, here at Caracol, flattened rather than true round or oval forms may have been desired.

Many of the giant glyphs are placed in four-lobed fields bounded by scalloped frames or borders. In Fig. 34 one has the periphery and the edge of the field only, extracted from the complete drawing of Fig. 35. Self-explanatory geometrical lines have been added. There seems to be little doubt that the designer found the four corners of a square, and constructed flat (not round) “arches” from them. This was a desired form, because it was more or less perfectly achieved for all other scalloped frames and borders at Caracol, and the form may be found, in various contexts, at other sites. Here, on this altar, this “flattened-arches” motif could have been fitted into a truly round periphery for the stone; instead the periphery is flattened on all four sides. While this distortion of the theoretically ideal circle is not great, it is noticeable; and if not perfect, the degree of symmetry is too high to be ascribed to chance. With this example before one, it seems less probable than before that Altar 14, shown in Fig. 40, was meant to be truly circular, though it is much more irregular; if that is let in as a member of an “irregular flattened round” group, it becomes difficult to exclude Altar 3 of Fig. 39, and so on with others. One suspects that the classification by peripheral form of Table 3 should be expanded to provide such a group, but the question is left open for the present.

Table 3. Sizes and Forms of Altars at Caracol

| (A) Giant-Glyph Altars | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis AA’ | Axis BB’ | Thickness | Form of Periphery | Supports if any | Stela if any | |

| Alt. 6 | 2.25* | 1.93 | .46 | Irregular Oval | Tripod | |

| Alt. 1 | 2.07 | 1.70 | .38 | Oval | St. 1 | |

| Alt. 5 | 1.93 | 1.40 | .40 | Irregular Oval | ||

| Alt. 14 | 1.82 – | 1.72 | .35* | Irregular Round | ||

| Alt. 19 | 1.81 – | 1.78 | .30* | Flattened Round | St. 11 | |

| Alt. 3 | 1.78 – | 1.77 | .35* | Irregular Round | Tripod | St. “X” |

| Alt. 4 | 1.77 – | 1.68 | .30* | Irregular Round | St. 9 | |

| Alt. 11 | 1.67 | 1.35 | .28 | Irregular Oval | Blocks | |

| Alt. 7 | 1.38 – | 1.28 | .24 | Round | St. 14 | |

| Alt. 17 | 1.36 | 1.08 | .32 | Oblong | ||

| Alt. 16 | 1.07 – | 1.03 | .30* | Round | ||

| Alt. 2 | 1.12 – | 1.17 | .30 | Square | ||

| Alt. 15 | ? | ? | .35 | ? (fragment) | ||

| Alt. 18 | ? | ? | .25 | ? (fragment) | ||

| *Approximate dimension, or based on reconstruction. Dimensions are in meters or decimal fractions thereof. | ||||||

| (B) “Scene” Altars | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt. 12 | 1.25* – | 1.25* | .46 | Flattened Round | St. 19 (?) | |

| Alt. 13 | 1.21 – | 1.16 | .30 | Irregular Round | ||

| Alt. 10 | 1.15 | .90 | .30 | Irregular Oval | St. 17 | |

| *Approximate dimension, or based on reconstruction. Dimensions are in meters or decimal fractions thereof. | ||||||

| (C) Unsculptured (“Plain”) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt. 9 | 1.20 | .93 | .20 | Oblong | ||

| Alt. 8 | .60? | .56 | .21 | Rectangular (Incomplete) | ||

| *Approximate dimension, or based on reconstruction. Dimensions are in meters or decimal fractions thereof. | ||||||

We may speculate a little further, not with too much assurance. As Morley has pointed out, what is here called a scalloped frame or border may be related to a glyphic “zero” or “completion” sign, usually incompletely shown in the inscriptions. It appears three times near the top on Stela 16 (Fig. 13). A completion sign would be very appropriate on a giant-glyph altar which named a katun by its ending day. If these scalloped forms are really completion signs, we should expect the observed flattening of their “arches,” for then their prototypes were glyphs habitually fitted into rectangular spaces. At any rate, it appears probable that, in origin, the flattened peripheries of at least some altars are esthetic adjustments to the frames, rather than that the lobes defined by the frames were flattened to conform to the peripheries. On the other hand, if the flattened round form first appeared as a reflection of the scalloped frame, Altar 12 indicates that later on it could appear without the frame; and, unless we are wrong in disregarding minor irregularities of Altars 1 and 7, the scalloped frame could appear without intentional flattening of the periphery of the altar.

In respect to the profiles of their edges, Altars 5 and 6 and Altars 12 and 13 form pairs which differ from each other and from all others. Space is lacking here for illustration and full discussion of variables in cross-sections.

Altars 3 and 6 were provided with plain but well-tooled tripod supports. The presumed original table-like character of these two was apparently eliminated later on by a raising of the pavement, which buried the legs. With one exception to be noted, all others were presumably or surely partially let down into the pavement from the beginning, so that variations in profiles of the edges would never have been very noticeable. The exception is Altar 11. This was found raised somewhat above floor level, its supports being three stone blocks, lying on their sides and unmatched as to size or form. These served as “legs,” but surely they were not originally intended for such a purpose. Because of this make-shift arrangement one wonders if Altar 11 may not have been moved from some other original location. It is not marked as “disturbed” in Table 1, because of the dubiousness of such evidence.

KNOWN ASSOCIATIONS OF ALTARS WITH STELAE

Table 3 shows that either “scene” or giant-glyph altars might be associated with stelae, but it suggests that rectangular ones were not-that is, among six sure and one fairly sure stela-altar pairs, only rounded altar forms are known. The two carved rectangular altars are giant-glyph ones. They agree in some unique details, including twelve “spots” and twelve “spot glyphs” which might have declared the dedicatory dates (Fig. 32).

One might suppose that Altar 6 never served a stela because it is of the tripod “table” type, but Altar 3 is also, and served “Stela X.” Similarly, the oval shape and enormous size of Altar 6 might seem unsuitable for a member of a stela-altar pair, but Altar 1 is oval and nearly as large as Altar 6, and served Stela 1 (Figs. 37 and 42). The data show no correlation between flattened or possibly flattened peripheries and those altars known to belong with stelae. There seems to be nothing in this table on which to base an argument that any rounded altar, not found with a stela, never served one.

It does appear as if only giant-glyph altars could range upward from moderate to really great size. One wonders if the altar of Stela Bl at Naranjo, reported to be about 2.00 m. in diameter, could have been a giant-glyph one. With advanced erosion, remains of such glyphs are easy to miss, especially before one has them in mind.

I will close with some remarks on placements of those altars known to belong with stelae. The distance between the two stones could vary widely-it was about .34 m. between Stela 1 and Altar 1, yet about .70 m. between Stela 17 and its small Altar 10. The latter have been placed closer together in the Museum because of space limitations.

Five of the six stela-altar associations establish a clear spatial relationship which, for convenience, may be analyzed into three elements. First, the center of the altar was meant to be opposite the center of the stela, but approximations in this respect were tolerated (Fig. 42). Second, the horizontal axis of the design was meant to be parallel to the face of the stela. Third, the bottom of the altar design was turned away from the stela so that as one stood before both he could look down and observe the altar, or look across it and observe the stela.

This pattern is precisely what one would expect, but Altar 19 fails to conform in the last two particulars (Fig. 34). Its center is almost exactly on the projected rear-to-front axis of the stela, but the axes of the altar are turned about 9 degrees-a very noticeable aberration. More surprising, from the usual observer’s position, after adjusting for this nine-degree deviation, the recorded 1 Ahau glyph is upside clown. Until such “upside-down” placement is demonstrated elsewhere, the best explanation would seem to be that it was the mistake of the riggers or, if placed by them as a blank, of the carvers. Perhaps the riggers were told to correct the mistake, whether their fault or not, started to, and then gave up. That would explain the nine-degree skew. Consistent with this idea is the fact that the stone was by no means perfectly level, but since this was observed nearly everywhere, settling is the probable reason for that.

* The list of those who helped us is a long one, and little more than financial assistance can be acknowledged here. The Univeristy’s Department of Anthropology, under the chairmanship of Dr. Loren C. Eiseley, covered the travel costs of two Student Assistants in 1951. The United Fruit Company loaded and transported some twenty gross tons from Belize to New Orleans, free of charge. Dr. A. V. Kidder, of Carnegie Institution of Washington. and Mr. Samuel Zemurray of the company were our friends at court. A very considerable sum was saved on rail freight thence to Philadelphia by the traffic experts of the Curtis Publishing Company. For this we must thank Mr. Brandon Baringer of our Board of Managers and the Curtis Company, and Messrs. Louis H. Palmer and D. D. Swanger of the latter. Funds supplied by Miss Anna K. Stimson, Research Assistant, were used in substantial amounts for repair and erection of monuments. once they were here, and in assuring a liberal amount of illustration for this issue of the BULLETIN. Incidentally, Fig. 16 is her work, based on a careful study of the original and on very fine photographs by Reuben Goldberg, our staff photographer. Most of the photographs of sculpture here published are from Goldberg negatives, made after repairs by Albert Jehle, our staff restorer. Horace Willcox contributed a great deal of time and hard work on the restorations long after his obligations as Student Assistant had ceased. He and two other graduate students, Seymour A. Nuddle and Jeremiah F. Epstein, each contributed about four months of time in the field, which helped a great deal budget-wise. So did the much appreciated assistance of the Public Works Department of the Colony in unloading heavy crates from the trucks which had brought them to Belize, the capital. ↪