The interest of the American public in Oriental research is proved by the foundation of the American Oriental Society in 1842, the very year of Betta’s discoveries at Khorsabad. Its first volume contains a paper on “The Persian Cuneiform Inscription and the Study of Egyptian.” But nearly half a century elapsed before public opinion matured and was ripe to enter the field of Mesopotamian archeoology. The first large-scale expedition to leave this country was the Babylonian Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania. It was organized in 1888 and supported by “The Public-spirited Gentlemen of Philadelphia.” Funds were subscribed and a corporation formed with Provost William Pepper as President and E. W. Clark as Treasurer. Other members were C. H. Clark, W. W. Frazier, C. C. Harrison, J. D. Potts, Maxwell Sommerville, Richard Wood, Stuart Wood, Prof. Langley (of the Smithsonian Institution) and Prof. Marquand (of Princeton).

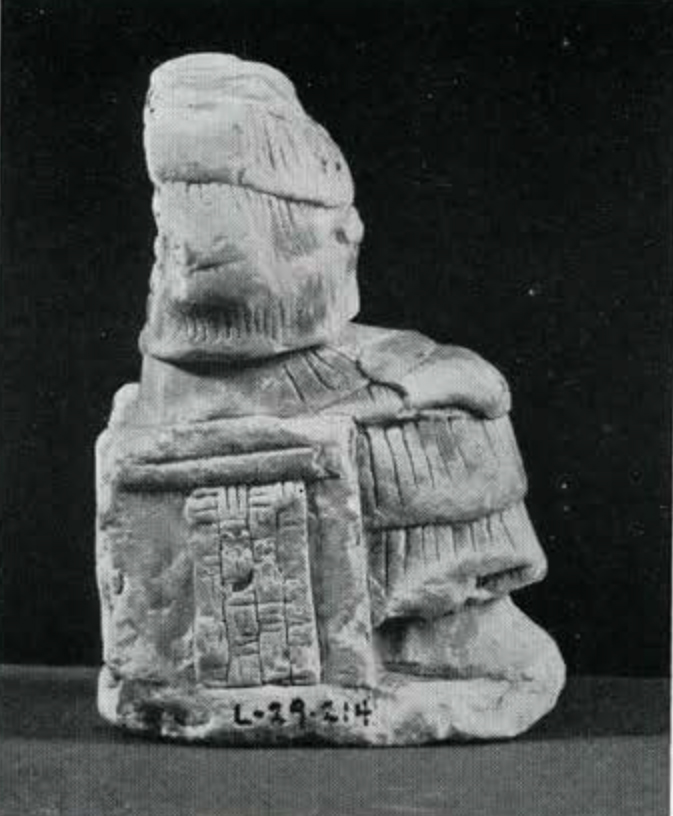

Museum Object Number: L-29-214

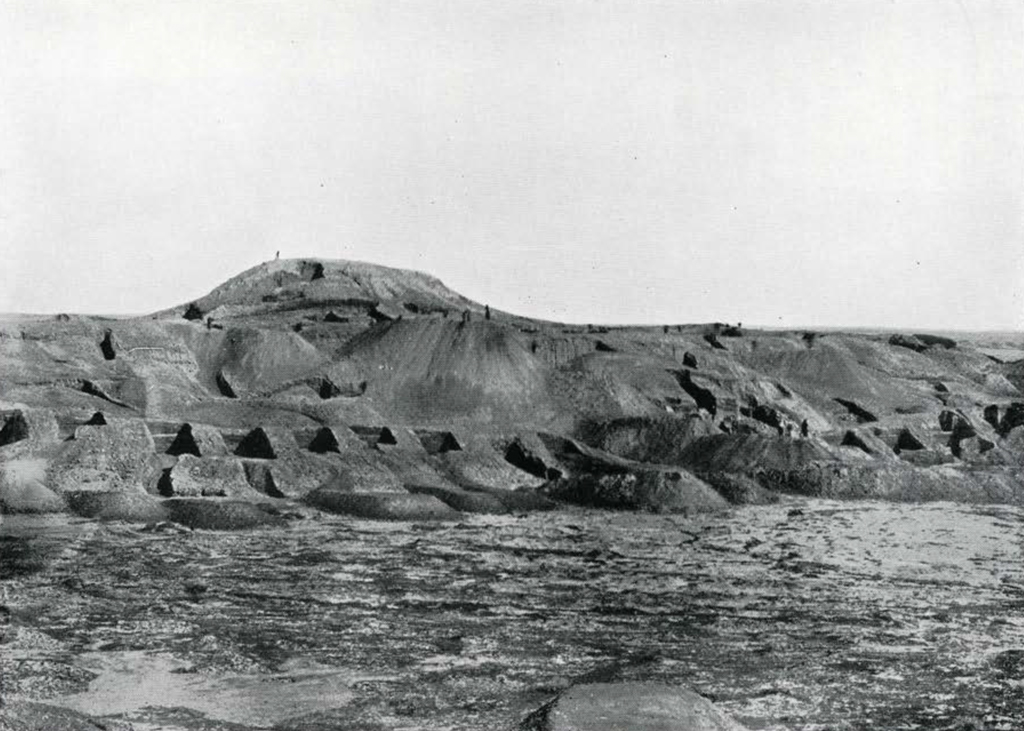

The site selected for the expedition was the mounds of Niffer or Nippur (Figure 2) in the middle of the Babylonian plain, a hundred miles south of Baghdad. Dr. John Punnett Peters was the Director in the field, assisted by J. H. Haynes. Prof. Herman Hilprecht, secretary of the expedition, whose name was henceforth to be intimately connected with Nippur, served as Assyriologist.

Thus was realized the wish expressed four years before at a meeting of the Oriental Society at New Haven: “Let us send out an American Expedition,” as a sequel to which a preliminary expedition had been organized in 1885, with funds provided by Miss Catherine Lorillard Wolfe of New York, under the control of the Archaeological Institute of America, with Dr. W. H. Ward of the Independent as director. Ward and his party visited southern Mesopotamia from Baghdad to Ur, stopping at Babylon and Tello. The Report on the Wolfe Expedition to Babylonia, published in 1886, blazed the trail for the Philadelphia expedition. The same year Dr. J.P . Peters was appointed Professor of Hebrew in the Department of Philosophy of the University of Pennsylvania and H. V. Hilprecht Professor of Assyriology. Their proposals to start a movement for exploring ancient sites under the auspices of the University were supported by the untiring Provost, Dr. William Pepper. On the thirtieth of November, 1887, at a meeting in his house, and with the active help of Mr. E. W. Clark, the banker, the Nippur Expedition was born.

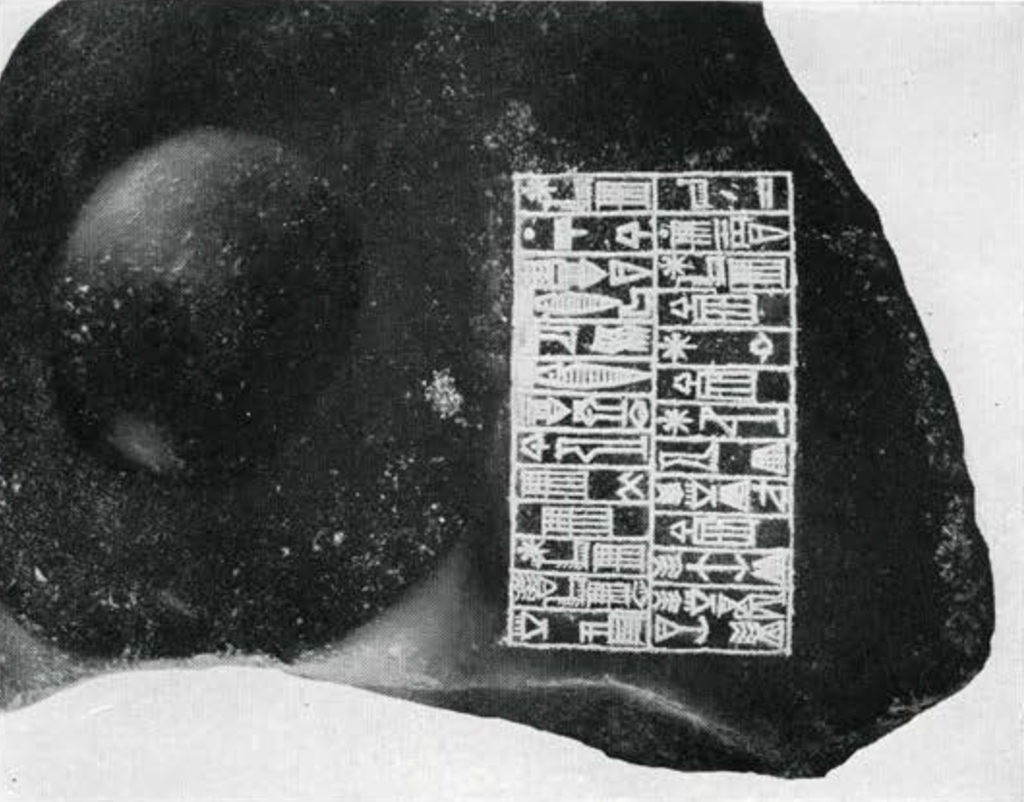

Museum Object Number: B8751

Image Number: 6903

The collections brought back in 1889 were received with growing interest. A new Archaeological Association was formed by Dr. Leidy. New sections in addition to the Babylonian were to be opened and a museum created to house them. In 1890 they were installed in the Library building, and Mr. Stuart Culin was appointed director. Monuments, tablets inscribed in the cuneiform character, rich material inviting research, were displayed. To answer the demand, the Department of Archaeology and Palaeontology was organized in 1891 by the University. In 1894, the Museum in the Library had become overcrowded. The necessity for a larger and independent Museum was realized by Dr. Pepper, who resigned his Provostship to become President of both Archaeological Association and Department of Archaeology. Funds were raised, ground acquired, and plans laid out. In 1898 the collections could be transferred to the new building. Dr. Pepper did not live to see the achievement of his dream. The Free Museum of Science and Art of the Department of Archaeology and Palaeontology of the University of Pennsylvania was opened December 20, 1899, by his successor, Provost C. C. Harrison. Association and Department were merged, and the ownership of the collections was transferred to the University. The Babylonian Section occupied one room of the upper floor, the Daniel Baugh Pavilion, then sufficient for an exhibition of the antiquities from Nippur, to which were added casts of important Assyrian monuments in the British Museum.

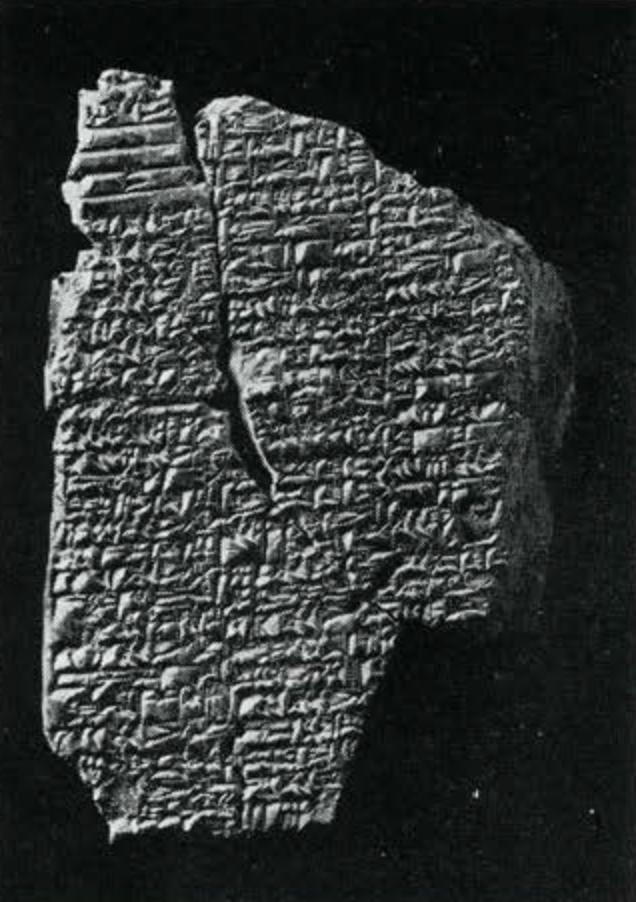

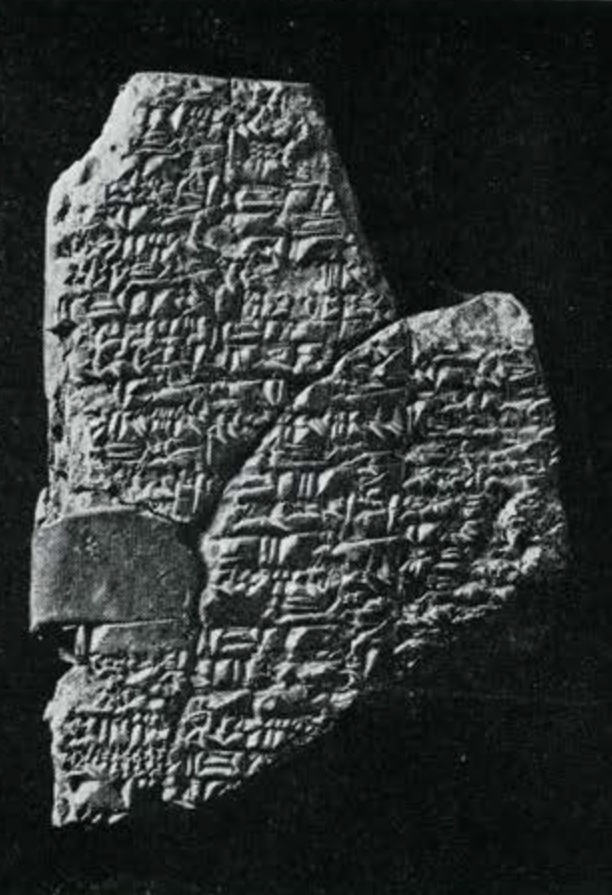

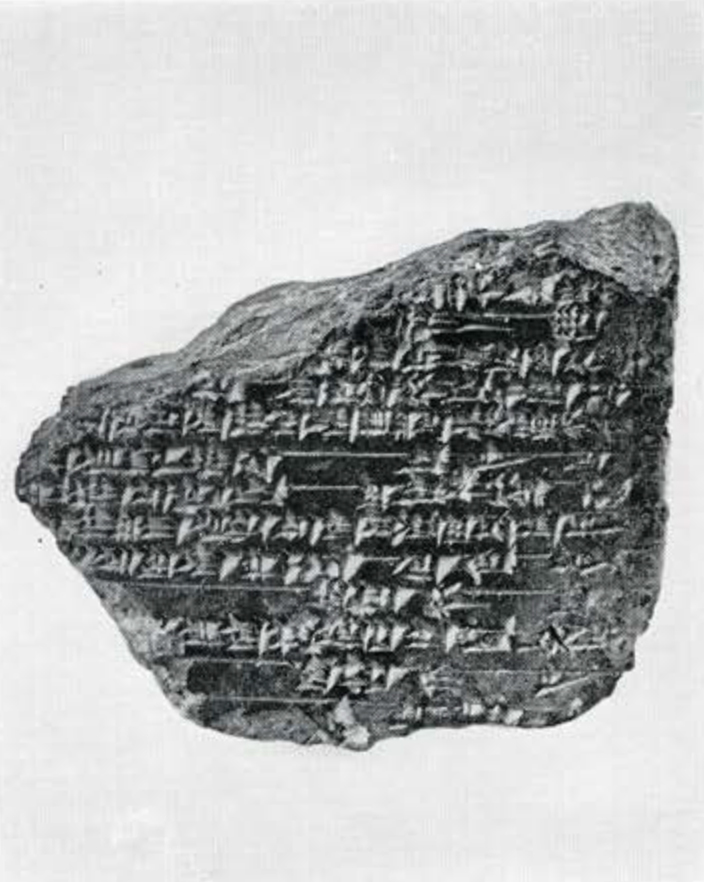

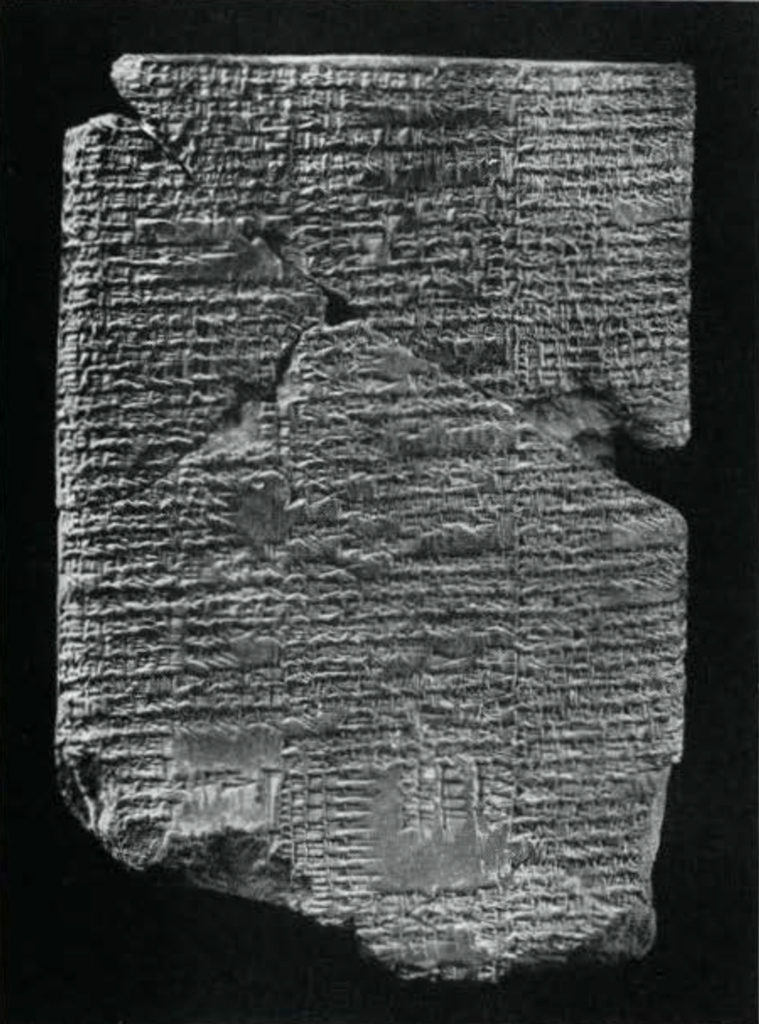

The Nippur collection of tablets has greatly contributed to the fame of the University Museum and has secured for it an outstanding position among the leading archaeological museums of the world. Probably more than fifty thousand tablets, inscribed in the cuneiform character have been recovered in the trenches, near the temple or in the business quarters of the city, where the records were stored in the narrow rooms of an archive depot or a school library (Figure 3). Part are preserved here, and part in the Museum at Constantinople. Over fifty volumes of historical accounts, cuneiform texts and translations and special works of research have already been published, most of them by the Museum, thanks to the Fund established by Mr. Eckley Brinton Coxe, Jr., sometime President of the Babylonian Section. Their subjects are as varied as the names of their authors: historical (Figures 4, 5,), legal, administrative documents, contracts, letters, religious texts concerning the Creation, the Deluge Story (Figure 6), Paradise, the Fall of Man (Figure 7), liturgy, psalms, hymns and prayers, the Epic of Gilgamesh, school texts of all kinds on grammar, mathematics, metrology, astronomy, lists of words and lists of proper names, representing many periods of culture, Sumerian, Babylonian, Cassite (Figure 8), Assyrian, Persian and Greek, during many thousands of years before the Christian era. The survey of other fields of excavations will make this clearer. A list of the scholars – from this country or from abroad – who, besides Hilprecht and Peters, deserve credit for their work on the Nippur texts is in order here. Many who came as pupils left as masters, Albert T. Clay, Hermann Ranke, William J. Hinke, Hugo Radau, Arno Poebel, David W. Myhrman, James A. Montgomery, Stephen Langdon, Edward Chiera, George A. Barton, Arthur Ungnad, Henry Frederick Lutz. A number of volumes deserve special mention: the first volume of the collection, Old Babylonian Inscriptions (1896) by Hilprecht, published with a grant of the American Philosophical Society; Nippur (1897), two volumes by Peters on the first three expeditions to Nippur; Excavations at Nippur (1905), the best account of the fourth Nippur expedition by Clarence S. Fisher, the architect, part published at his own expense-and never finished; Excavations in Assyria and Babylonia (1904), a popular volume by Hilprecht, covering the whole field of Mesopotamian archaeology, Nippur included; A New Boundary Stone of Nebuchadnezzar I from Nippur (1907) by Hinke; Aramaic Incantation Texts from Nippur (1913) by Montgomery; and two volumes by the present author on the seals (1925-27) and the terracottas (1930) of Nippur in the Museum collections. At the present time, Dr. Samuel N. Kramer, the associate curator of the Babylonian Section, is engaged in translating the Sumerian literary texts and has published the results of his work under the auspices of the American Philosophical Society and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

The methods of excavation of the last century were still crude, and may be, to a certain point, excused by the wealth of written records secured by Peters and Haynes. The Sumerian temple of Bel (Enlil) at Nippur, was essentially a great stage tower, built on an artificial brick platform, surrounded by an open courtyard and a fortified wall, with the main gate opening on an outer court. Shrines were erected at the level of the court on either side and probably one on the lop of the tower, as will be shown at other sites. Staircases led to the summit. The original temple was often rebuilt and enlarged in the course of time. The small mud tower disappeared below massive revetment of baked bricks. The level of the court was raised and new pavements covered the accumulated debris buried in the sacred ground. The names of the rulers who across centuries restored the temple, are stamped on their bricks, a mark of their devotion and a help to an exact chronology. Layer after layer tells its own history. Unfortunately, at Nippur a huge Parthian fortress of later times covered the forgotten tower of Bel and had to be removed before the first stages of the old construction appeared. An enormous shaft was sunk in the court in front of it, down to the virgin soil, with only moderate attention paid to the succession of strata partly exposed, and the refused soil was piled, mountain-like, over the surrounding walls. The great gate, of which the two door-sockets-inscribed with the name of Shargani-sharri, King of Agade, circa 2600 B.C.- are now in the Museum, was first located by the architects of the fourth expedition. The plan of a fifth expedition on a more scientific basis never materialized and must await more propitious days.*

Museum Object Number: B4561

Museum Object Number: 29-20-1

Image Number: 6860

* Excavations were resumed in 1948 by a Joint Expedition of the Chicago Oriental Institute and the University Museum. ↪