The Museum has recently acquired three colossal Chinese frescoes which, we may state without exaggeration, are among the most important works of art that have ever come out of China. Artistically they are amazing in the grandeur of their conception, the power and rhythm of their line design and the glorious subdued harmony of their colouring. Historically they are priceless, as hitherto no frescoes of such proportions and majesty have been known to exist in that part of the world from which they have come. Indeed, up to within a few years ago it was thought that the great frescoes painted on the walls of temples and palaces during the Tang dynasty and so extolled in Chinese literature had all perished long ago. Travellers reported the buildings destroyed without leaving a trace and it was generally assumed that no Chinese frescoes of an early period would ever be found. Expeditions under Von le Coq, Count Otani and Colonel Kozloff have discovered fragments of wall paintings in Turf an and other parts of Central Asia, but they could hardly be called Chinese. In an expedition of 1906 to 1909 Sir Aurel Stein visited the caves of the Thousand Buddhas at Tun Huang on the far western border of China and since then he, M. Pelliot, and others have made known to the world the wonderful frescoes there, and fragments of paintings on silk, many of which were at once recognized to be of unquestioned Tang date. However, the presence in these paintings of Turfanese characteristics and the fact that many of them showed provincial workmanship would seem to place them outside the central traditions of Chinese art.

The Museum had already acquired in 1925 a set of five mural paintings from the walls of a cave temple in Honan province. They were of much beauty of line and colour and occasioned considerable surprise and comment. But as these frescoes, together with similar examples that appeared in Europe and America at the same time, were usually single figures cut from the walls and thus dissociated from their companion figures and surroundings and as there was no definite data in regard to them, their chief effect, apart from the recognition of their artistic merit, was to prove that frescoes did still exist in Central China, for their style was such that the statement in regard to their provenience was accepted as probably correct. Accessories and various characteristics of technique led us to judge that they were executed in the Sung or Yuan period, somewhat later than the era in which painting was said to have reached its greatest heights. However, their existence held out a faint hope that some time, in some hidden and forgotten mountain monastery near the old seats of Chinese civilization, some fresco of an earlier period might be brought to light.

Image Numer: C492 / C493 / C494 / C692

Image Number: 1442, 1445, 1476, 1477

This hope has been realized in the new frescoes acquired by the Museum. And expectations have been so far exceeded that these three frescoes appear as a revelation. For they are tremendous in size and overwhelming in their majestic presence. As one enters the hall which they now seem to dominate and stands facing them he cannot repress a feeling of awe at the sight of the great Buddha rising some twenty feet above him and gazing down with the strange green light about his temples and hair.

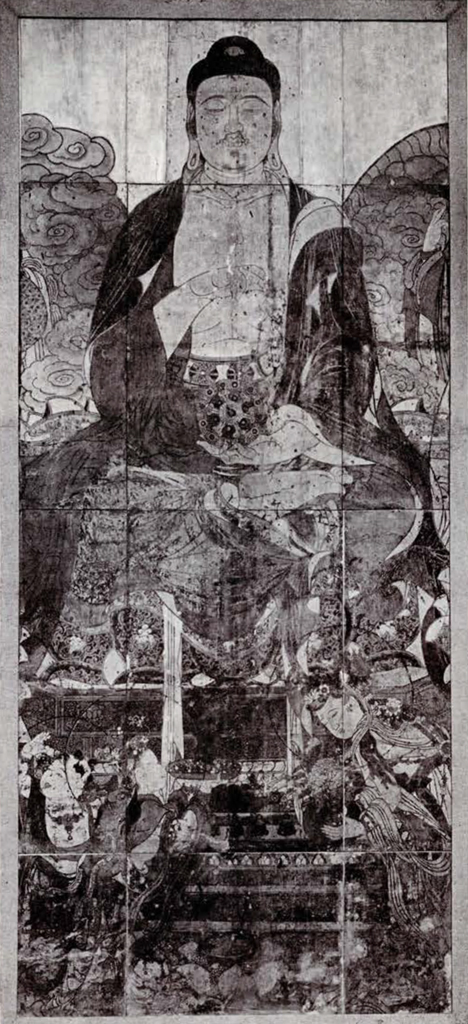

There are three panels as they now stand framed on the wall of Charles Custis Harrison Hall, also a small section belonging to the left panel but not at present framed with it. Originally these all belonged together, forming parts of one enormous painting which must have been at least forty feet long and twenty-five feet high and may have been even larger. We will describe the three panels before explaining the composition of which they formed a main part.

The great Buddha facing us in the central panel is Sakyamuni seated on an elaborate dais with legs crossed and each foot resting on the opposite thigh, with soles of the feet turned up, a posture known as padmâsana. In his lap he holds on the palm of his left hand the wheel of the Law which he has just been turning with his right hand. The large though not massive head is set on a heavy neck and strong shoulders with great dignity and poise and the face bears a serene half dreamy expression. The three most prominent marks of beauty and holiness are all represented; the ushnisha or protruberance of the skull which formed a sort of bump of wisdom on the top of his head; the urna or spot on the forehead between the eyebrows, from which rays of light were said to have shone in times when he was inspired; and the long ear lobes which are so admired by Eastern peoples and were considered a sign of holiness. The garments are plain and consist of a long red under robe which falls over the knees and around the ankles, a brilliant emerald green scarf, which is draped from the Buddha’s right shoulder, is looped up over the right arm and then sweeps down across the right knee to the throne, and on top of these a rich dark red, almost maroon, cloak lined with buff, which merely laps over the right shoulder but swathes the whole left side and arm in heavy folds which fall back over the left knee and drape themselves on the throne below. The hair is a deep purplish black with some indigo blue in it, and edging it all around the forehead is a strange green which touches up the eyebrows and mustache and beard also and lends an uncanny light to the face. Flesh tones are light tan. The Buddha’s breast is bare to the waist, where a brocade belt in tan and green appears behind the bejewelled wheel of the Law.

Image Number: 1445

The figure sits on a large cushion with a rich brocade pattern in blue, green and tan, and this in turn rests on a throne of which the details can hardly be made out, but the upper part of which is evidently a low octagonal platform of emerald green resting on another similar but smaller platform. Below in front of the throne are three figures, one of a child with its head shaved except for a few tufts of dark hair and the other two of young and feminine looking Bodhis-attvas presenting offerings to the Buddha. The child has his back to the throne and is raising his right arm as if calling to some playmate to come. The figure next to the child, with her profile upturned towards the right, is holding up a large golden yellow platter full of pearls and precious stones, out of the midst of which rises a branch of deep red coral. The third figure leans from the right and, while looking back over her left shoulder, starts to raise, with a graceful gesture, a large blue bowl of chrysanthemums. Below this the fresco is much worn and one can make out only rows of lotus petals, tassels, and what appear to be steps, all evidently belonging to the throne, the ends of long scarfs and, directly in front, a huge lotus seed pod looking like a green bowl resting upon petals and stamens. It will be noticed that the heads of the three small figures are provided with halos which are merely black circles.

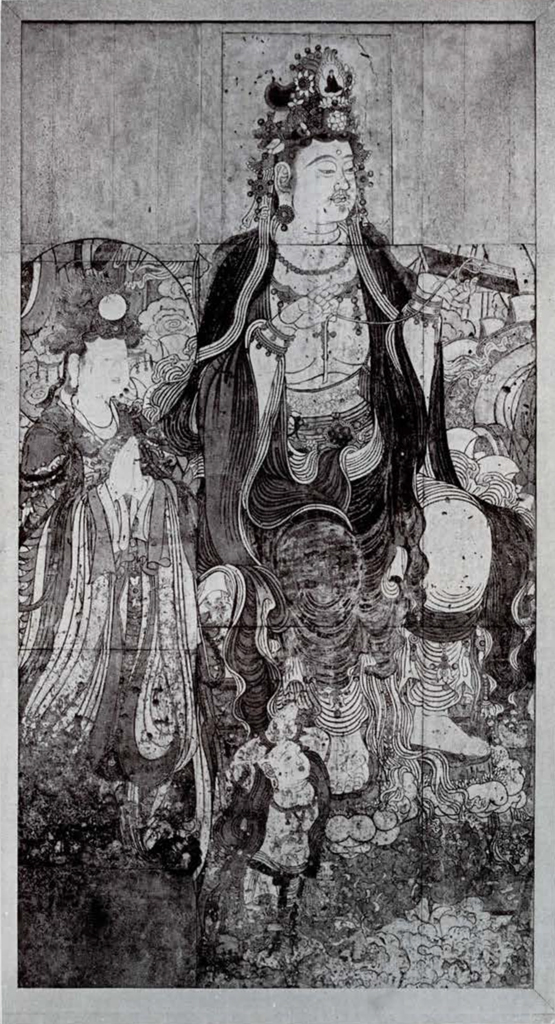

The panel on the left is only less impressive than that of the Buddha. The figure is that of Avalokitegvara, the Bodhisattva of Mercy, known more familiarly as Kwan Yin. The tiny figure of a Buddha in the headdress leaves no question as to this identification. This huge Bodhisattva, represented as male after the Indian tradition, is seated in European fashion and is turned three quarters toward the central Buddha. One is struck with the gorgeousness of the adornments in contrast to the plainness of the Buddha’s garments, for here is a high jewelled headdress with streamers and pendants descending on either side, elaborate earrings, necklaces, bracelets. An undergarment of white is draped in many parallel folds over the knees and across the shins. Over this a robe of red appears. A scarf of blue falls from the right shoulder, is caught up over the arm and descends to the chair below. Over all, just lapping over the right shoulder but completely covering the left side, is a great deep red cloak. The flesh tones are light tan. Both forearms are raised in the act of untying the cord of a book which the Bodhisattva holds in his left hand. Beside him on his right stands a smaller figure, that of a graceful female deity holding her hands in an attitude of adoration. In the front of her elaborate headdress, which is a mass of emerald and blue feathers and precious stones, is set a large creamy oval jewel. Her emerald and tan garments sweep back in long unbroken lines and there is a halo drawn around her head. Below, at the foot of Avalokitesvara, stands a child figure facing toward the Buddha and throwing both arms above his head with hands clasped in adoration. This figure has no halo. The fragment of fresco already mentioned belongs to this panel and should adjoin it on the left side. It bears the figure of an attendant to the deity with the creamy oval jewel, a dainty female Bodhisattva without a halo but wearing a bejewelled headdress and carrying a hare in her hands.

The scene on the right hand panel is different from these other two. It depicts an important personage in robes befitting an emperor approaching the Buddha’s throne with hands held in the attitude of adoration, while accompanying him is a small delicate female figure and following behind is an official looking gentleman who bears a large golden yellow platter upon which lie three peaches. Back of this procession are the figures of two demon kings in fantastic armour. The upper one, with a bright green face, bears a sword; the other, with a blue face, carries over his shoulders a huge snake which rears its head between the two demon kings and opens its jaws threateningly. The garments of the imperial figure in the foreground are most magnificent. A white under robe appears at neck, wrists, and in front. Over this are emerald green robes, brocaded borders, olive brown flaps, all in many folds. The upper garment is a bright red robe with heavy embroidery around the neck. Cream coloured ribbons tied in bows on each shoulder descend to the hem of the dress. Jewelled chains are suspended from the girdle and jewelled bands are draped over the upper arm. The elaborate hat is tied on with a ribbon bow under the chin. Set conspicuously in the front of the hat is a large black oval jewel. The small female figure beside this royal one wears a beautifully bejewelled headdress, but otherwise her garments are quite plain, a simple white over blue with a bit of olive and emerald green in the borders. Her hands are covered by her sleeves. The official bearing the peaches is in blue with borders of cream and purplish brown relieved by a touch of emerald green. Both this official and the imperial looking personage have halos drawn around their heads, both have long beards and mustaches indicated by fine straight black lines drawn parallel and barely veiling the outlines of lips and chin. At the left side of the panel appears a section of a very large halo which intersects that of the imperial personage, the area of their intersection being represented opaque.

When the frescoes were removed from the walls of the monastery they were taken off in oblong sections cut like large flat tiles, the edges of which may readily be made out in the photographs. In the whole picture we recognize unmistakably a composition familiar to us through the frescoes and paintings from Tun Huang.

We have here three out of the five most important portions of a Paradise Scene. The picture appears again and again on the walls of the caves of the Thousand Buddhas, where, however, the central figure is usually Amida rather than Sakyamuni Buddha. From analogy we can visualize the whole scene, supplying the missing parts from our knowledge of what must have completed the composition.

The great figure of Sakyamuni occupied the center of the picture. Seated on his right was Avalokitesvara. The corresponding figure on the left must have been Maitreya, as this completes the usual triad. Behind the throne, between the Buddha and each of the great seated Bodhisattvas, was a standing Bodhisattva. We can make out the arm of the one on the Buddha’s left. Sometimes these positions were occupied by the monks Ananda and Kasyapa, but as the arm in this case wears bracelets the figure must be that of a Bodhisattva. Rising from the Buddha’s shoulders are arcs of a circular halo behind his head, a halo which was opaque. The Avalokitesvara had such a halo also, the lines may be seen at the shoulders. So doubtless had the Maitreya on the other side to correspond.

The panel of the Buddha and that of the Avalokitesvara are adjoining; no part of the picture has been lost between them. On the other side, however, considerable of the fresco is missing between the Buddha and the procession of imperial looking deities. The Maitreya formerly occupied this space. The scalloped edge of his throne appears on the central panel just below the Buddha’s left knee. On the panel of the procession the edge of the huge transparent halo running into a smaller opaque one at the top, of which only a small arc is visible, suggests that these notables stood directly to the right of the Maitreya. It is probable that all three of the main figures, the Buddha, Avalokitesvara and Maitreya, had huge body halos as well as the smaller ones behind the head. Most of the Tun Huang paintings show this feature. Certainly the huge arc on the procession panel could hardly belong to any other figure than Maitreya. Moreover, behind the book that Avalokiteśvara is holding appear two lines which I believe are arcs of the intersecting body halos of the Buddha and the Avalokiteśvara.

Who is the personage depicted in royal robes adoring the Buddha? One thinks immediately of the figures of donors which appear so frequently in pictures of this kind. The faces of the “Emperor” and his official appear to be portraits. Yet there are three features present which are not consistent with this view, the presence of halos, the black oval jewel in the headdress which in some way connects this figure with that of the female deity standing beside Avalokitesvara with a similar but cream coloured jewel in her headdress, and the significance of the peaches which the official is bringing as an offering. The hat of the “Emperor” is very like those worn by some of the Taoist deities as depicted in the album of drawings owned by F. R. Martin and long considered as copies from works by Wu Tao-tzu of the T’ang dynasty. These Taoistic deities wear halos, whereas we know of no emperor so deified as to have acquired a halo in a Buddhist painting. The peaches are well known Taoist symbols of immortality. Incidentally the hare is another such symbol and is associated with the moon, where he is supposed to live and pound the elixir of immortality in a mortar. The figure carrying the hare corresponds in size, position in the composition, garments, headdress, and even design of earring to the small figure accompanying the “Emperor.” There is certainly a connection. Do we have here some stellar or planetary deities of Taoistic origin? Indeed, it is probable that the Bodhisattva with the creamy oval jewel in her headdress is none other than T’ai Yin Hsing, Taoist Goddess of the Moon, while the figure we have called the “Emperor ” represents T’ai Yang Hsing, the Taoist Sun God.

Image Number: 1476, 1477

At least the two figures behind the “Emperor” and his following are familiar. They represent two of the four demon kings or lokâ-palas, guardians of the four quarters of the universe. The one carrying a sword is Virüdhaka, Guardian of the South, the other, with the snake over his shoulders, is Virupaksha, Guardian of the West and King of the Nâgas, or Snake people. Their colours should be blue and red respectively, but here we find that the artist has represented them as green and blue, probably to fit in better with his colour composition. That their colours are less fixed by convention than their other attributes is illustrated by the fact that when these guardians are represented in Japanese art the colours have been changed about completely. As for the other two guardians, Kubera of the North and Dhritarâshtra of the East, in our fresco they were doubtless in a corresponding position on the opposite side of the picture to the left of the Avalokitesvara, belonging on a panel now missing, which matched the procession panel just discussed.

Thus we have reconstructed the scene in its main outlines. The Buddha seated cross legged on a throne in the center, turning the wheel of the Law, on one side the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, on the other the Bodhisattva Maitreya, both sitting in European fashion and turned slightly toward the Buddha. Behind each great Bodhisattva a number of minor Bodhisattvas and perhaps monks and beyond them the demon kings two on each side. Near the front, advancing from both sides, Taoistic deities tendering adoration. In the immediate foreground children and young girl Bodhisattvas making offerings.

All this is closely akin, not only in conception but in many details, to some of the frescoes of Tun Huang. There is the same scheme of arrangement, the same position of the great Bodhisattvas—sitting in European style. There are the large halos around the three main figures, besides the small halos behind their heads, only in the Tun Huang paintings the large halos as well as the small are opaque and frequently ornamented with rather barbaric marbled designs. Minor deities approaching in procession from the right occur in many of the Tun Huang paintings and are sometimes accompanied by smaller attendants on each side. Children appear at the foot of the throne in several of the paintings and Bodhisattvas hold up jewelled caskets, vases, and plates of precious stones as offerings. Almost every paradise scene has in it one or two Bodhisattvas who stand or sit with their profiles turned to us as they make their offerings, and some of these figures bear striking resemblance to the one in our fresco, both in drawing and in physiognomy.

Such similarities as these force us to acknowledge that the paintings of Tim Huang were composed according to a generally accepted arrangement for such subjects and that the painters in many respects followed the central school of painting closely. But that the fresco in the University Museum belonged to that very fountain head of painting which was the inspiration of the provincial schools, we cannot doubt when we note the differences. For this fresco far excels in majesty and artistic worth. In most of the Tun Huang frescoes the darks and lights are spotty, many details, such as the halos, are barbaric in design, the composition has no rhythm or life as a whole, although parts do; whereas here the contrasts do not startle or confuse but make a harmonious composition of darks and lights, the spacing is characterized by that feeling for grandeur which is one of the greatest elements in the best Chinese art, and the line design as a whole as well as in details is most wonderfully unified and rhythmical, everything in the composition rising to a peak in the great dominating figure of the Buddha. There is a more ample spaciousness here, a finer sense of grouping and subordination, better taste in details. Whether there existed in this fresco as in most of the Tun Huang Paradise scenes the dancers and musicians performing in the foreground we cannot tell. We would conclude not, however, both because the design does not seem to require it and because the condition of the frescoes at the bottom of the panels suggests that they came near the foot of the wall where rubbish was perhaps piled against them and dampness destroyed the surface. Whether there were canopies, landscapes and other details above is also uncertain.

Image Number: 1470

The technique is not that of true fresco. The walls were plastered with mud mixed with much chopped straw and over this a smoother but still rather gritty coat of reddish brown clay was spread. The painting was executed upon the dry wall with body color, the thickness and opaqueness of which suggest tempera. The style is characterized by heavy outlining in black, the lines being sure, strong, unbroken, and of even width. Here they sweep in long rhythmic curves, there in snake like coils. The flesh tones of the female deities are painted white in contrast to the creamy tan colour of the masculine figures. Another convention is the use of cloud scrolls to fill up the background. There is no trace of gold on the paintings or any use of moulded stucco such as one finds occasionally outlining jewels or other details in the frescoes of Tun Huang and those of later periods. It is the simplest, most straightforward kind of painting, depending purely upon its artistic qualities and deep sincerity for its appeal.

The colour design is magnificent and deserves a few words to itself. Yet the colours used are few and not unusual. Red and green predominate but are of such degrees of saturation, used in such varying quantities and so skillfully arranged in spaces of different shapes and separated by tans or blues, that the result is one of subdued, if rich, harmony. There are two reds, the one a very dark one almost maroon such as the upper garments of the main figures are painted, the other likewise deep and rich but with a certain smouldering crimson in it. The green most used is an opaque emerald green which, placed by itself, shines out brilliantly, but next to smaller quantities of a blue of equal saturation produces a delightful peacock effect. The green used about the faces of the Buddha and Bodhisattva is intense and weird but there is very little of it. There is also but a small quantity of an olive green which appears here and there in the draperies. Throne, headdresses, jewels and brocaded borders are in emerald green combined with the corresponding blue. Flesh tones and much of the drapery are a creamy tan. The warm tone of the wall upon which the fresco was painted has done much to give these colours something in common, the tan of the background being a strong unifying factor. Indeed, the colours shine out from it like medieval jewels in a dull golden setting. Another unifying factor has been the use of the black outlines which separate the colours like the leads of a stained glass window and themselves tend always to flow toward the great central figure, rising to a climax in the deep blue blacks of his hair.

In regard to the place from which these frescoes came and the date of their execution we have some evidence. From their character and style, comparing them with the dated work of Tun Huang, we should say without hesitation that they belong to the same general period, that is, to the T’ang dynasty, and that they came from a district where the influences were purely Chinese, probably somewhere in Central China. Striking similarities in detail actually exist between these frescoes and some of the Tang pottery, especially the mortuary figures in the Museum. Painted borders representing brocade are very much alike in their design, and in both figures and frescoes these borders display an almost exclusive use of the two colors, blue and emerald green, with the outlining in black. The phoenix birds represented in the headdress and on the neck embroidery of the Moon Goddess are of exactly the same type as those forming the headdress of two grave figures of lokâpalas. Another correspondence may be seen between the designs on the throne of the Buddha and the borders engraved upon a T’ang stone pedestal and on one of the slabs of a horse of T’ang T’ai Tsung.

Another strong argument in favor of attributing the frescoes to the T’ang dynasty is the masculine character of the Avalokiteśvara. By the Sung dynasty this Bodhisattva had assumed a more feminine aspect and there was no trace of mustache or goatee as appears here. Finally, the very deep religious feeling so apparent in this picture is characteristic of T’ang rather than later times. Later works did not have this grandeur and power, this mysticism about them.

The types of Buddha and Avalokiteśvara are those said to have been established by Wu Tao-tzu, the greatest painter in Chinese history if we can believe Chinese traditions about him and his work. He was born about 700 A. D. He is said to have painted over three hundred frescoes in the region around Loyang, near the present Honan Fu, and the capital Ch’ang-an, present Si-an Fu, but apparently not a trace of these frescoes now remains. His influence was enormous. His name has been a household word in China and in all circles where Chinese art is known. The great triptych of Buddha, Manjusrî and Samantabhadra, painted on silk, in Tofukuji Temple, Japan, is thought to be an original by his hand. Our fresco has not the tremendous power and energy of line seen in the triptych of Tofu-kuji but it is certainly a work made under the influence of the same great master. The rosette system of line design centering in the position of the hands of the Buddha recalls that of the Manjusrî panel just mentioned. The procession of Taoistic deities, also, has close affinities with some of the drawings in. the so called Wu Tao-tzu album owned by F. R. Martin. The manner of drawing the mustache and beard in fine parallel lines is traditionally T’ang. The robes of the Avalokiteśvara are like those in the descriptions of some works by Wu, “like coiled copper wire.” The cloud forms such as fill the background occur in other Tang paintings, few as they are, for instance, the Hokké Mandala in the Boston Museum. In fact, we cannot but reach the conclusion that this fresco was painted in the latter part of the Tang dynasty when mystical Buddhism was still strong and when Wu Tao-tzu’s style of painting predominated. This would be either just before the suppression of Buddhism in 845 A. D. or more likely just after its revival some thirty years later.

There are several short Chinese inscriptions on the lower part of the painting—another indication that not more than two or three feet of fresco are missing at the bottom, for these characters are mostly names written carelessly by pilgrims to the temple. One inscription somewhat longer and more carefully written than the others occurs on the light space under the right sleeve of the “Emperor.” It is a prayer and may be translated thus, “Exalted public official Tan desires wind and rain in proper quantities and at proper times upon his land.” This is interesting but not especially enlightening.

According to information that we already have regarding these frescoes they come from a mountain monastery of Honan province which tradition says was built in the T’ang dynasty. The district from which they are said to come is not so far from Loyang and the region where Wu Tao-tzu did much of his work that it would have escaped coming under the influence of that tremendous personality. Thus the data already at hand tends to confirm our judgment concerning these frescoes.