JUST north of the Yellow River and crossing nearly at right angles the main trunk line from Peking to Hankow is a short branch of railroad connecting Tao K’ou Chên on the River Wei with the town of Ch’ing Hua Chên in Honan Province. Ch’ing Hua Chên lies about twenty miles away from the Hoang Ho and is diagonally across it from Honan Fu. Behind the town rise the mountains, piling up over the border into Shansi Province. It is because of the rich coal mines in these mountains that the railroad was built, to get the precious material down to the waiting junks on the Wei, whence it is carried on to the Grand Canal to be distributed throughout Chihli.

These mountains along the Shansi-Honan border contain other things besides coal, things precious in a different way, remains of the bygone glory of a religion still revered but of an art no longer practised. Some five miles from Ch’ing Hua Chên, up in the mountains, are three old Buddhist temples, long forgotten now and in a sad state of ruin, with few to care what happens to them. The central one of the three is known as Yüeh Shan Ssŭ, “Moon Hill Monastery,” built, it is claimed, during the Tang dynasty, 618-906 A.D.

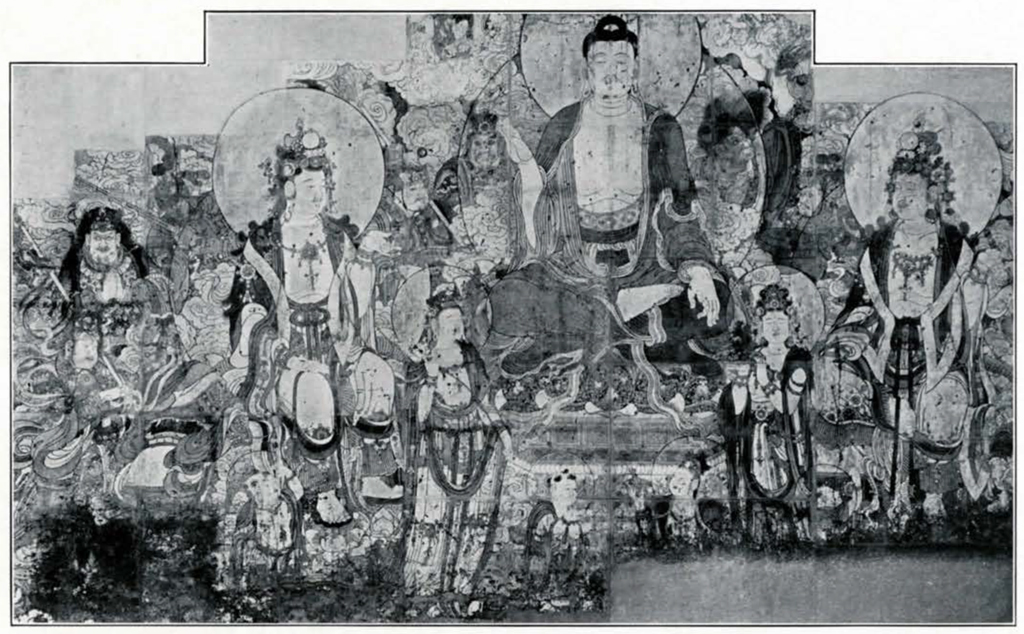

Two years ago the larger part of a huge wall painting said to come from the main hall of Moon Hill Monastery was acquired by the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM and published in the MUSEUM JOURNAL for September, 1926. Although parts of it were missing, the scheme of design was obvious and the dimensions of the whole could be estimated. It was seen to have been the decoration of a wall about twenty-five feet high and forty feet long, a truly colossal painting.

Within the last few months the nearly perfect fresco from the opposite wall of the same hall has been brought over and purchased by the MUSEUM, being now installed in Charles Custis Harrison Hall in its place opposite the other. Tremendous and awe inspiring as the first was, this fresco actually overpowers it in grandeur and impressiveness. This may be partly because it is more complete, but it is also because of the greater intensity of colour and greater massiveness of the Buddha figure in the centre.

Museum Object Number: C688

Image Number: 1483

The general scheme of composition is the same on both walls, the essential figures on the one having their counterparts on the other. They are practically of the same size, the style is the same, and the technique is identical. It is evident, as one looks from the one to the other, that they are parts of one plan of decoration, made to balance each other, painted at approximately the same time. Each wall has in the centre a colossal Buddha seated crosslegged on a throne, while on either side of him, sitting in European fashion (i. e., as if on a chair) and turned slightly in toward the Buddha, is a great Bodhisattva. All have opaque halos behind their heads and large transparent body halos. Surrounding them are lesser Bodhisattvas, child devotees, demon kings, and other deities. Cloud forms fill the background. In design the style is that of the T’ang dynasty, known to us through the frescoes and paintings of the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, at that little town on the far western border of China, Tim Huang. Both of the paintings from Yüeh Shan Ssŭ were done on walls of coarse reddish mud mixed with straw surfaced with a thin layer of slightly finer clay. In both cases body colour was used, opaque, like tempera, and looking like enamel where it was put on thick. Outlines are black and heavy and of even width. As in the case of the first one, the second wall painting was removed from the temple by cutting it out in huge oblong sections from behind. The new painting is eighteen feet in height and twenty-nine feet long. Making allowance for the four missing figures on the right, the top of the Buddha’s halo, and a foot leeway all around, the wall from which this came must have been of the same dimensions as the other.

A photograph of the new fresco is reproduced as frontispiece. It will be seen that the centre of this painting is occupied by an immense figure of Śâkyamuni Buddha seated on the lotus throne padmâsana (that is, crosslegged with the soles of the feet turned upward in the lap), his right hand raised in abhaya mudrâ, his left hand resting upon the left knee. The Buddha’s hair is blue black with green lights along the temples and eyebrows. His great breast is bare to the waist, but over each shoulder falls his rich crimson red garment which sweeps around the left arm down into the lap and envelops the right leg. The left leg is swathed in a deep green which appears again at the waist. The right sleeve of the emerald green undergarment is set brilliantly in this juxtaposition with the red. Borders and scarfs are emerald green and the belt is of a beautiful blue and green brocade. Śâkyamuni sits on a brocade cushion of elaborate pomegranate pattern in tan, blue, and green, and this in turn rests upon the octagonal throne which is made up of panelled platforms and mouldings in cream and green. Flesh tones are a rich tan.

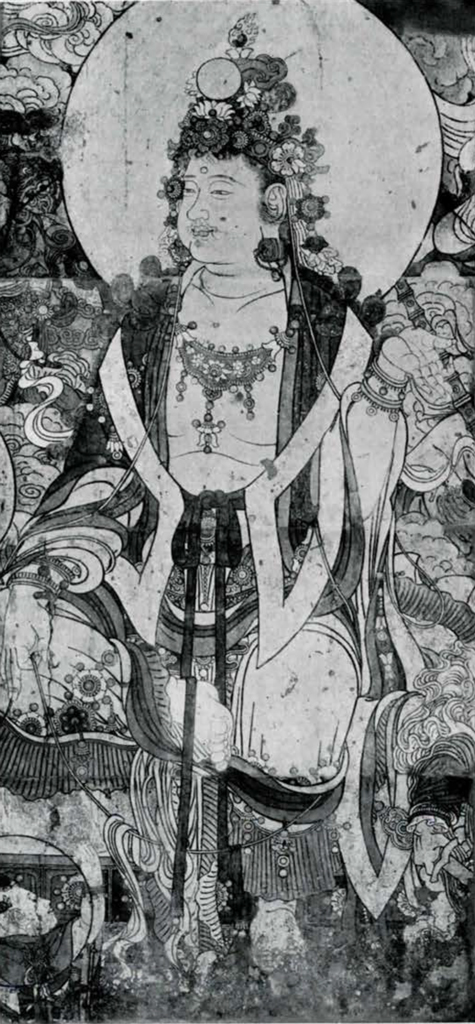

The great Bodhisattva sitting European fashion on each side is turned toward the Buddha, presenting to us a “three-quarters profile.” These figures are most elaborately dressed in garments which have long scarfs and ribbons and many jewelled chains. The colours here are cream for flesh tones and tunics, over which the deep rich blues and brilliant emerald greens of cloaks and scarfs and flounces weave a pattern of great beauty. In the high bejewelled headdress of each shines a large oval disk (a pearl?) and a flaming jewel (cintâmani) crowns the top. Their feet rest upon large lotus flowers. In the foreground, at the front of the Buddha’s throne, stand two graceful Bodhisattvas, one on each side between the Buddha and the seated Bodhisattva. The one on the left holds a lotus with a long stem; the one on the right, a shallow dish full of pearls and green and blue gems out of the midst of which rises a thick branch of red coral. A third Bodhisattva, smaller, kneels (presumably, but the lower part of the body is on a part of the wall that is defaced) in front of the throne at the right, holding up a small glass bowl with a pomegranate in it, while on the left of the centre the figure of a child devotee stands with hands clasped in adoration. A child worshipper appears also at the feet of each of the huge seated Bodhisattvas and raises its arm in salute.

Surrounding this peaceful group of adoring and adored are a number of military looking figures clad in a strange combination of armour and jewellery and carrying all sorts of Buddhist paraphernalia. They are very probably devas—supernatural beings. Through the transparent halos we can see four behind the Buddha’s throne. On the right next to Śâkyamuni is a wild looking dark one with flying hair and loose collar, holding up a flaming jewel. Beside him is a deva in armour holding what seems to be either a large alms bowl(?) or a kind of drum. On the left side is first a deva with hands clasped and then another in armour with a long beggar’s staff, called a khakkhara, over his shoulder. The left end of the fresco is occupied by four devas. One in front with his back turned holds what seems to be a sceptre-like dagger, a vajra, in his hand; flowing garments almost hide his armour and his headdress is of jewels. The deva next to him is in armour with the heads of demons on headdress, sleeves, and belt. He holds a long staff, from the ornamental pike-like tip of which streams a long narrow banner. Above these two stands a deva with clasped hands wearing a demon head on his cap. Behind him is a dark, fierce figure with heavy helmet, lunging forward with a long sword.

Museum Object Numbers: C688.10 / C688.11 / C688.11 / C688.13 / C688.14 / C688.15 / C688.16 / C688.17 / C688.18 / C688.19

Image Number: 1487

To complete the symmetry we should have four more devas on the right side. But this portion of the fresco is missing. The hand of one, however, grasping a sword, appears in the lower right hand corner of our painting and above it may be seen the hand and shoulder of a second, with a bamboo pole crossing the background.

In colour the whole is magnificent. Cloud scrolls which fill the background are mostly a deep cream but become a light emerald green when behind the Buddha and some of the other figures. The central figures have already been described. Although the colours are pure and bright, there is so much tan and cream and the spaces are so varied that the result is most gloriously harmonious. The blue, green, and tan passages, especially, have the simplicity and softness of a fine Japanese print. The crimson of the Buddha’s robe, however, dominates the whole wall and the figure is so powerfully drawn that it fairly seems to jut out from the plane of the wall in most striking contrast to the comparative flatness of the other figures. The huge Bodhisattvas are in prevailing tones of tan, blue, and emerald green with touches of mulberry and dull gold for variety. The one on the left has coppery red hair. Beyond them the devas provide a rich and more complicated pattern made up of all the colours used, and here appears again, in small quantities, some of the intense red, an answering note of colour which echoes the crimson at the centre and draws the whole picture together in one complete harmony.

A word on the identification of the figures is not amiss. The seated Buddha appears to be Śâkyamuni, with the right hand represented in the abhaya mudrâ. The two great seated Bodhisattvas are probably Âkâśagarbha (Hü K’ung-tsang) and Kşitigarbha (Ti-tsang). Hü K’ung-tsang was “the essence of the void space above,” a personification of the air. He is not often met with in Chinese art except in this common triad, with Ti-tsang, attendant upon Śâkyamuni. But his companion, Ti-tsang, was a great favourite, especially after the seventh century, when the sûtra telling of his vow to help mankind had been translated from the Sanskrit into Chinese. Indeed, his popularity almost equalled that of Kuan Yin and we should quite expect to find him occupying the place of honour on this wall corresponding to that of Kuan Yin on the other. The name Ti-tsang is commonly translated “Earth Womb.” He is the compassionate lord whose khakkhara shakes the gates of hell and whose gleaming pearl illumines the region of darkness. As the Odra says, “When he touches the doors of hell with his staff they are burst asunder, when he passes the gloomy portals and holds forth his radiant jewel the darkness of hell is dispelled by rays of celestial light.” The Bodhisattvas making up the usual triads with Śâkyamuni are Kuan Yin and Maitreya, Kuan Yin and Ta Shih-chih, Wen-shu and P’u-hsien, and Hü K’ung-tsang and Ti-tsang. The requirements for the first three pairs are not fulfilled, the fourth remains as a possibility. Although the figures themselves carry no attributes, there are various indications that these do represent Hü K’ung-tsang and Ti-tsang. The Bodhisattva on the right is sitting in the position called lalitâsana (one leg pendent, the other crossed in front of him), an attitude considered characteristic of Ti-tsang. Moreover, Ti-tsang’s two chief attributes are actually being carried in the background by two attendant devas, the one holding the beggar’s staff with its loose rings and the other a flaming jewel, as has already been noted.1The attributes of Hü K’ung-tsang, who would therefore be the Bodhisattva on the left, are the sun disk and a flower. Perhaps the smaller Bodhisattva standing by the throne on that side with a huge long stemmed lotus in both hands may be considered the bearer of the attribute. In the clouds high above a sweet faced apsaras (heavenly nymph) appears with a basket of flowers. Probably the beings whom we have so far called devas are the ten Kings of Hell who often accompany Ti-tsang and from whose punishments the Bodhisattva seeks to save mankind. The two guardian dvârapâlas would account for the total of twelve figures of military mien.

Some time early in the Tang dynasty, or even before, there seems to have become established in sculpture and painting a certain traditional composition for representing the Buddha with two attendant Bodhisattvas and a host of other adoring beings. Over and over again we see it occurring on the walls of the Caves of a Thousand Buddhas; over and over again it appears in the paintings on silk, many bearing Tang dynasty dates, which were found by Sir Aurel Stein at Tun Huang about ten years ago. The two great frescoes in the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM conform to this same traditional scheme of arrangement. Points of similarity between the Tun Huang paintings and the other wall were noticed in the JOURNAL of September, 1926. We should like to note here the striking analogies between this new fresco and a stone lintel of the Tang dynasty in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,2 a lintel which is engraved with a scene obviously, as Mr. Ashton remarks, based on a painting. The Buddha surely is not Maitreya, however, but Śâkyamuni, for he is attended by Kâśyapa and Ânanda, the old monk and the young one, which should be a sure sign of Śâkyamuni. Dr. Siren interprets the position of the left hand as bhûmisparśa mudrâ, but the writer’s attention has been called to the fact that this mudrâ was not represented with the left hand. It is true that among the Stein paintings there are several examples in which the Buddha is shown with the left hand on the knee, and that this position has been described as bhûmisparśa mudrâ in spite of the fact that the right hand is at the same time in vitarka mudrâ [Ch. xx. 009 and Ch. 0051.] The attitude of the left hand of the Buddha in the paper drawing Ch. 00159 is noticed, however, as “left hand clasping knee,” and this explanation seems to me to apply not only to the cases just cited but to the Boston lintel as well, and to the Buddha of the new wall from Ch’ing Hua Chên. The right hand of the Buddha on the Boston lintel is in the attitude of varada (boon giving). That the Bodhisattvas seated on either side are possibly Ti-tsang and Hu K’ung-tsang has been pointed out by Prof. Siren, doubtless a correct identification, for upon the knees of the one are representations of the sun disk, while in front of the throne on each side kneels a little Bodhisattva, the one holding out a large lotus on a long stem, the other offering a large pearl in a dish, the respective attributes of the two great Bodhisattvas. The angles of the lintel have been crudely cut off, but portions of the figures of four guardian kings remain and three of them display their attributes, so there is no difficulty in identifying them. It is likely that the painting on which this engraving is based was a version of the Sâkyamuni, Hü K’ung, Ti-tsang triad very similar to the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM fresco. In the fresco the two monks and four guardians are replaced by the ten Kings of Hell and two guardians(?), the two kneeling Bodhisattvas are made to stand, while adoring children are added in the foreground. Cloud scrolls take the place of the tree. But it is in certain minor details that the most surprising similarity is seen. The plaited flounce around the bottom of the skirt of the Bodhisattvas is prominent on the lintel, the method of depicting the long locks of hair falling down the Bodhisattvas’ backs is identical on both. The lotuses under the feet of the Bodhisattvas, the double outline of the petals of the Buddha throne, the brocade belt of the Buddha, the lotus flower held by the little Bodhisattva on the left of the throne, the drawing of hands, noses, chins, and necks, all are strikingly similar. The same “properties” are used, too; for instance, the little glass bowl or cup, which in the fresco is held up by a kneeling Bodhisattva in the foreground and contains a pomegranate, and the vajra (a kind of dirk or sceptre) held in the right hand of the guardian dvârapâla on the left. Bracelets and the lotus flower hair ornaments are identical. With all these similarities noted, we cannot avoid the conviction that the new fresco in the UNIVERSITY MUSEUM and the engraving on the Boston lintel have a closely related origin, not, probably, in the same painting but in two varieties or versions of the subject painted by the same hand.

Museum Object Numbers: C688.20 / C688.21 / C688.22 / C688.23

Image Number: 1501, 1502

What was said in regard to the style of the first fresco,3 which we may call the Kuan Yin fresco for convenience, applies here also and need not be repeated. We may add, however, that among the enormous number of frescoes painted by Wu Tao-ter on temple walls near Ch’ang-an and Lo-yang (over three hundred, we are told), there must have been many representing this popular triad, Sâkyamuni, Hü K’ung, and Ti-tsang. It is probable that Wu established several versions of the subject which, due to the powerful influence of his name, became models upon which later paintings were based. However, since there seem to be no absolutely authentic examples in existence of the work of Wu Tao-tzu, and since the descriptions of his paintings are so intangible that we know very little of what they actually looked like, we can only point out the possibility of some such reason as this for the obvious similarities of design and detail in this fresco and the Boston lintel.

Very few Chinese frescoes, of early date at least, are known to exist today. Yet literature tells us that enormous numbers of them were painted during the T’ang period and earlier. It was a veritable golden age for fresco. From the middle of the fourth century A. D. (the time of the painter Ku K’ai-chih) until 845 (one hundred years after Wu Tao-tzu) the fervour of the Buddhists expressed itself in a remarkable wealth of artistic creation. Sculpture and painting blossomed forth in the service of this religion, reaching heights they have never attained since. The greatest artists of the time, and there were many, decorated literally hundreds of temple walls with paintings of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Among them were, early, Chang Sêng-yu, later, Yen Li-pen, Wang Wei, Han Kan, and, acknowledged master of all ages, Wu Tao-tzu. Yet apparently not a brush stroke remains, on wall or fragment of wall, from the hand of any one of these painters! In 845 A. D., under the Emperor Wu Tsung, an attempt was made by the conservatives to abolish all foreign religions.4 Nearly 5000 great monasteries were torn down and, so we are told, over 40,000 smaller temples. The greatest art of the T’ang period, the work of the most famous masters, perished irretrievably. Of the hundreds of works by Wu Tao-tzu, for instance, only one fresco seems still to have been in existence in 1085, seen by the poet and art critic Su Tung-p’o in the Lung-hsing Ssu, at Ju-chou, Honan. When the Emperor T’ai Chung came to the throne in 847 the edict for the destruction of temples was revoked, but it was then too late to recover what was lost and when temples were again erected the wall-paintings had to be restored mainly through copies or by memory, as Mr. Yetts notes. Another general demolition of Buddhist temples occurred in 955, but it was not quite so sweeping. When, besides these periods of destruction, we remember that Chinese architecture is light and inflammable, we do not wonder that none of the famous wall paintings have survived. Nevertheless, frescoes of an early period are being discovered in China and a number of fragments have in the last few years been brought to America and Europe. Most important among these are the beautiful examples in the British Museum and those in the Fogg, the Metropolitan, and here. Most of these fragments are the figures of Bodhisattvas or of child devotees cut out from the wall separately and without any clue as to their position in a group, if there was a group. Only in this MUSEUM do we find a complete wall—or nearly complete.

Because of the comparatively few examples of frescoes left, their fragmentary condition, and the lack of definite data as to when they were painted, it is at present almost impossible to place them in their correct periods or even to arrange them in a proper sequence. As Mr. Binyon rightly remarks in his work on the frescoes of the Eumorfopoulos Collection (in the British Museum), “where we have so little knowledge, conjecture must be diffident.” There are good reasons for assigning the Moon Hill Monastery frescoes to T’ang, to Sung, or even to Ming. Artistically, of course, it does not matter in the least. If a work of art is food for the spirit—if it is beautiful and powerful and soul stirring—its date is of little importance. Like a Beethoven symphony or a Pavlowa dance, it conveys a message eternal and timeless. On the other hand, historically the date is important. For a people is revealed through its art. It is only by means of art and literature that we can reconstruct a civilization of the past, understand it, make it live again. If we know that a painting is of a certain period, we know, at the least, something of the setting for the people of that time. At the most we are given a keener insight into the thoughts and emotions and aspirations of those who made it and had it made. No one can look at these impressive frescoes from Ch’ing Hua Chên without feeling a closer bond of sympathy with the Chinese of that time and a desire to know more about them and the religion which could produce such magnificent works of art. At present we can give these paintings a tentative dating only, as there seems to be too little evidence available now for solving the problem.

In my previous article, at the time when only the Kuan Yin wall was known, I ventured the opinion that the painting was of late T’ang date, executed certainly after the persecution of 845 A. D. and probably during the very last years of the T’ang dynasty. Mr. Binyon feels, I believe, that the flatness of the painting and its strongly emphasized decorative quality indicate a later date than the fresco of the three Bodhisattvas in the Eumorfopoulos Collection, a painting from Ch’ing Liang Temple, Chihli, in which the feeling for form predominates even over line design, and which may perhaps be a late T’ang production (although he hesitates to do more than express such a possibility). Mr. Yetts considers it highly improbable that any frescoes of a period so remote as the Tang dynasty could have survived the vicissitudes of war, persecution, fire, and dilapidation to which Chinese temples, at least in the central part of the country, have been subjected in all these years, and thinks that these frescoes justify “a recognition in them of the T’ang tradition rather than an actual attribution to that period.”

It is generally admitted that the Kuan Yin fresco is of a T’ang composition, painted in the T’ang tradition. If so, it must either be of that time, or be a later exact copy (a reconstruction), or a “free version after the old style,” made from memory or following the guidance of an old wood cut or drawing. What proves to be true for the Kuan Yin wall will apply to this second one.

Mr. Yetts called attention to the folded book in the hands of the Kuan Yin on the first wall and suggested that the title on the cover might afford a clue to the date. We had been working for some time on this previously, but the third and fourth characters were injured so as to be almost illegible. Experiments with photographing this detail have shown up some strokes, however, and Mr. J. E. Lodge, who most kindly offered his aid, has succeeded in deciphering the title which he “would provisionally read”

an abridgment of

“the Fo Shuo Ch’ih Shêng Kuang Ta Wei T’e Hsiao Tsai Chi Hsiang T’o Lo Ni Ching,” in Sanskrit, ” BuddhabhafitatejalVrabhd-mahilbalkuvdpadvinaSagridhdravisatra,” i. e. Buddha’s teachings concerning the dispelling of calamities, translated into Chinese by Amoghavajra (746-771 A. n.). The title on this book is not a later addition; it was executed at the same time as the fresco. Thus I think we are safe in assuming that these frescoes could not have been painted before the end of the eighth century. Probably 800 A. D. is the earliest date which we need consider.

Museum Object Numbers: C688.4 / C688.7 / C688.5 / C688.8 / C688.6 / C688.9

While obviously the twin brother of the Kuan Yin fresco, the new painting from Ch’ing Hua Chen overpowers the former in one respect. One’s first impression upon looking at it is that the huge figure of the Buddha is jutting out from the wall—it seems almost to protrude into the room, so huge and massive and heavy does it appear. The outlines are definite and strong, emphasizing the decorative design; there are no such ” tactile values” expressed as are felt in the Bodhisattvas from Ch’ing Liang Temple, now in the Eumorfopoulos Collection. Yet the figure has a tremendous sculpturesque quality which is especially striking because the others around it are so flat; it has a weight, a third-dimensional element, which, in contrast to them, amazes and puzzles us. The head is not so strong; it is the body which fairly emerges from the wall. Inevitably one’s mind harks back to the Italian masters, working with their apprentices, and recalls, too, that the power of imparting “tactile values” to a figure is the gift of the individual artist and not of the period. The lack of it may not prove anything.

The probability of preservation of such huge paintings as these from even the closing years of the T’ang dynasty is not great, but it is a possibility. One remembers that the wall paintings of the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas are all in tempera (with one exception). The surface of the Ch’ing Hua Chen paintings is hard and enamel-like, and although the coarse texture of the clay wall beneath is hardly to be compared to the hard foundation examined by Stein, it is very enduring and the gritty mixture of clay, straw, seeds, and little pebbles makes a sort of tough stucco. A good protecting roof would have kept the frescoes in a splendid state of preservation indefinitely. Incidentally, it would seem that this mountain region along the border between Shansi and Honan is exactly the place where such frescoes might best stand a chance of preservation, for the temples there seem to have been just enough off the beaten track and just sufficiently inaccessible to have escaped the attention of iconoclasts. At any rate, it is out of this very region that most of the fresco fragments recently found have been brought to light. The set of fourteen, mainly single figures of Bodhisattvas, now in the Eumorfopoulos Collection, is said to have come from a cave temple five miles north of Yüan-ch’u Hsien on the Yellow River, a distance of about sixty miles due west of Ch’ing Hua Chên. This MUSEUM has five figures which seem to belong to the same set but are said to have come from Honan. Turin has two similar figures and the Fogg Museum two. If not from the same temple in Shansi, these are surely from neighbouring ones which might be either in Shansi or Honan. All these frescoes are at present considered to belong somewhere between the middle Sung and early Ming (1100-1500 A. D.). The types of Bodhisattvas are too feminine for an earlier date and some of the accessories that appear in the panels are characteristic of the latter part of Sung, if not of Yuan or Ming. The Shansi frescoes are in a different technique from that of the Ch’ing Hua Chen wall paintings, a technique more nearly that of true fresco but with a soft, chalky surface. One would expect it to crumble and disintegrate far sooner than the hard, firm surface of the Ch’ing Hua Chen paintings. Yet they are, most of them, in a very good state of preservation. All of which merely goes to prove that these frescoes from Moon Hill Monastery might be, as regards preservation, considerably earlier than the Shansi ones.

The design of the new wall, like the Kuan Yin one, is founded closely upon the Tang tradition. The decidedly masculine type of the great Bodhisattvas testifies to that. Also, from the tenth century on, according to Dr. Siren, Ti-tsang was usually represented as a priest; previous to that, like other Bodhisattvas. This painting would seem to be according to the tradition in or previous to the tenth century.

The Chinese were not given to making exact copies. Even in the case of silk paintings where the two rolls might be laid side by side, the copy was more likely to be what we should call a “free version.” In the case of a wall painting the size of this one, the chances of its being an exact copy are very small. Neither does it have the ear marks of a copy; it is too magnificent, too convincing, too sure technically. If it is “after” a T’a.ng design, it is a free version constructed upon a general arrangement of composition that was traditional and conformed to the old masculine type of Bodhisattva. Old rules regarding attitude and gesture must have been followed also. Indeed, we see a striking illustration of this very fact of traditional type and attitude in comparing the two walls ; the figure of the Kuan Yin and that of Hu K’ung-tsang are almost identical. The painter could use the one model for both by changing the costume, attributes, and position of the hands; he could change the position of the feet, he could doubtless introduce all sorts of variations in the matter of attendant figures, he was allowed free fancy in the matter of accessories and properties. In fact, these two walls from Moon Hill Monastery are versions of each other in much the same way that they are versions of some older, well established type of composition, some more famous painting or paintings. We may guess that the Moon Goddess and Sun God were introduced into the composition on the Kuan Yin wall because the Moon Goddess was worshipped on this mountain. The name might indicate that—Moon Hill. There is plenty of evidence to show that the Buddhists adopted these Taoistic divinities and nature deities into their pantheon. The frescoes of Moon Hill Monastery might well show details not known in the original prototypes.

Museum Object Numbers: C688.16 / C688.17 / C688.18 / C688.19

Image Number: 1496

If later copies are not ” copies” but ” versions,” is not our best chance of a clue to the date likely to be found among the details, accessories, and properties in these paintings? Can we find in the frescoes of Moon Hill Monastery any detail, article, or trick of drawing which could not possibly belong to the closing years of T’ang but must belong to a later date? So far I have been unable to discover in either painting, any one thing which can be considered conclusive evidence that the frescoes were executed later than the period to which I tentatively assigned the first, namely, the very end of the T’ang dynasty. The time should properly be considered as an art period, however, rather than a political one, a period of reconstruction of temples after the destruction of the middle ninth century and before the artists of the Sung era had had opportunity to develop the newer soft and feminine types. Thus if this belongs to the last period of T’ang painting it may actually have been executed at any time during the tenth century. In the MUSEUM these frescoes bear the label, ” Probably Tenth Century,” an assignment which may seem more satisfactory than ” End of T’ang,” although but few years are involved.

Most of the details, properties, and mannerisms of drawing may be paralleled in the Tun Huang paintings and earlier frescoes, though not all of them in any one example. Some of the properties are almost matched by similar objects in the Shosoin. There are several puzzles, however. The folded book in the hand of the Kuan Yin on the first fresco raised the question of the possibility of such an early date. It is known that the folded book came into common use at the beginning of the Sung dynasty soon after printing was used to reproduce copies of the sûtras. Among the Stein finds is a beautiful wood block print serving as frontispiece for a printed roll and bearing the date 868 A. D. The folded book surely followed closely after such work as this and it is not impossible that the tenth century saw such books as not uncommon. That point has yet to be established. It may be noted for what it is worth that the Samantabhadra of the Tofukuji Triptych, long attributed to Wu Tao-tzu, holds a folded book in his hands, and that what appears to be a box of folded books is depicted in an engraving on jade which was inscribed with a date of the period 907-911 A. D. and which Dr. Laufer reproduces from the Ku yü t’u p’u, a Sung catalogue of the Emperor’s collection of jade, prepared in 1176. It is possible, however, in regard to this jade engraving, that the lines which we take to indicate separate folded books may merely represent the edges of trays made to hold rolls—and anyway there is too much in the Ku yu t’u p’u that is open to doubt for us to place a great deal of reliance on any evidence from that source. Most convincing, however, is the appearance of a folded book in one of the Stein paintings, Ch. lvi. 0019, Thousand Buddhas, P1. XVII. As the horde of documents among which these paintings were found was, apparently, walled up in the late tenth or early eleventh century the evidence for the existence of folded books previous to that time is fairly conclusive. Another point which raises a question is the manner of depicting the flame from the radiant jewel held up by one of the kings. This flame is usually represented as a sort of aureole behind the jewel ; here it is like a tassel at the end of a rope. A wave pattern on the second platform of the Buddha’s throne seems characteristic of Ming but may go back much earlier. Simpler forms of it may be seen on a few of the T’ang bronze mirrors in the Shosoin and on a Wei tablet in this MUSEUM. Offerings of coral do not seem to be made in the Tun Huang works, but there may be T’ang representations of it known. The peculiarities of drawing which appear here and there in these frescoes are seen also in the Tun Huang paintings and may be accounted for in the same way. It does not take long for the mannerism of a powerful artist to become a stereotyped convention in the hands of his lesser followers, great as they may be in many ways.

As in the case of the Kuan Yin wall, this new fresco bears all along the lower part of it the scribbles of visiting pilgrims. Many of these inscriptions of one to eight characters are partly or wholly illegible. The bottom of the wall has lost its surface completely, owing, it would seem, to the accumulation of dirt and rubbish on the floor of the hall. Perhaps about four feet is gone and with it the lower characters of some of the writings which were put on, generally, at about shoulder height. Mr. Quentin Huang of the University of Pennsylvania has been able to decipher a number of the less defaced scribblings, but as yet has found nothing to give a clue to the date except the characters Jên Tsû written in a large hand on the flower vase of the Kuan Yin wall. Jên Tsû is the name of the forty-ninth year of the sixty year cycle and might have been written as recently as 1912! There is a faint chance that among the names will be found that of some well known personage of early date whose autograph on the wall (if it was actually written by himself !) would prove that the painting existed as far back as his time at least. There are a good many names among the thirty-five or more scribblings. Others are mere comments like: ” Upper wall; leather shoes; the foot; rice; east; day; flute.”

A scribbling on the arm of one of the child devotees reads: ” This is what is done by one who does not know the rites.” A familiar quotation appears, ” The blowing of a flute alarms people early in the morning.” Several Buddhist phrases such as, “Tao Ch’ang,” the Place of the Way, or a chapel; “Ch’êng Tao,” to attain Nirvana; etc. One sentence seems to have been scratched here by a youngster who wanted to curse other boys, and reads (the second character is defaced), “The dogs . . ought to die.”

The fact remains that the decorative style of these frescoes is different from anything that we yet know of authentic T’ang work and this is the greatest, and so far the only, argument against a tenth century attribution. Parts, such as the detail of the two figures in front of the throne, are in general character much like the Stein paintings belonging to the T’ang period; but other parts, such as the deva kings, are treated in a wholly different way, quite unlike the figures of guardians in the Tun Huang works where detail never seems fussy or over emphasized. The design, the power and impressiveness of these frescoes we associate with T’ang paintings, but there is present here also a strong tendency toward the subordination of form to line design, a quality which we have always hitherto attributed to later periods of art in China. It seems impossible to reach any definite conclusion as to date until more material shall be known for comparison or some literary evidence shall be found.

Museum Object Number: C688.2

Image Number: 1517

In spite of the fact that so many questions yet remain to be settled in regard to these frescoes, it seems best to publish this second wall from Moon Hill Monastery at this time in the hope that it will stimulate the discovery of new evidence and at least add to the amount of known material on the subject of Chinese wall paintings. No illustrations in black and white can do justice to these magnificent works, however, and it is hoped that a monograph with coloured plates may be issued at a later date presenting clearly all details at present shown too small for study. Incidentally, we are glad to say that we have located a large part of the lost portion of the Kuan Yin wall, which, it is to be hoped, will soon be reunited with the others and may afford some further information.

In closing this introductory paper, let us state again that the evidence still seems to us strong for a tenth century attribution, although by no means conclusive. These frescoes might have been made by artists who were engaged in restoring to their former splendour those temples which had suffered in the ninth century persecutions, or in providing with frescoes those new temples which became established at that time. They would be in a style not yet out of date at that time but far enough removed from the prototypes to show certain conventions. In regard to a later dating, it seems to me highly improbable that these frescoes were painted in the Sung period, more likely that they are Ming—if the tenth century hypothesis proves untenable. Whatever their date these two great wall paintings from Ch’ing Hua Chen stand today nearly complete, works of tremendous power and impressiveness, strong in spiritual quality, a glorious witness to an art and beauty that are eternal.

1 The almsbowl–if it is that–would be another bit of evidence, as it is a third common attribute of Ti-tsang.↪

2 Siren: Chinese Sculpture, Plate 439.

Ashton: An Introduction to the Study of Chinese Sculpture, p. 91, Plate 53, Fig. 1.↪

3 See MUSEUM JOURNAL for September, 1926.↪

4 Buddhism, introduced from India in the first century, was a heavy sufferer.↪