QUEEN SHUBAD was so fond of her jewels that when she died in ancient Ur, six thousand years ago, they buried her in queenly state with all her regalia, so that her spirit might have rest. After so many centuries this treasure of feminine adornment is still a delight to the eyes. Her golden comb, her wreaths and diadem, earrings and necklaces, amulets and garters, finger rings, pins and seals, the silver box with black stibium paint for her eyebrows, her golden cockle shells and the golden chalice full of the purple-blue of turquoise for her eyelids, the thirteen yards of golden ribbon wound about her hair, the stiletto, the tweezers, the ear-spoon, the dainty implements of her vanity case, make us wonder at the richness of the material, the skill of the workmanship, and the good taste of the objects once spread ready for the royal hand in the queen’s boudoir and today displayed in a freshly decorated room of the Museum, where we can satisfy our curiosity.

Museum Object Numbers: B16693 / B16992 / B17709 / B17710 / B17711 / B17712

Image Number: 8313

We like to think that the queen was a brunette with a mass of dark hair, which, alas, has long turned to dust in the grave. Her skull, irremediably damaged by long exposure in a clay soil, was found collapsed on the bier. Only the gold ribbons wound in a gentle spiral about her head retained their position and to a certain extent outline her coiffure. We wonder what she looked like in the days of her splendour, whether she wore a wig, or her natural hair dressed after the fashion of the time; and what were the fashions for ladies of quality at the court of Sumerian Ur in 3500 B.C.

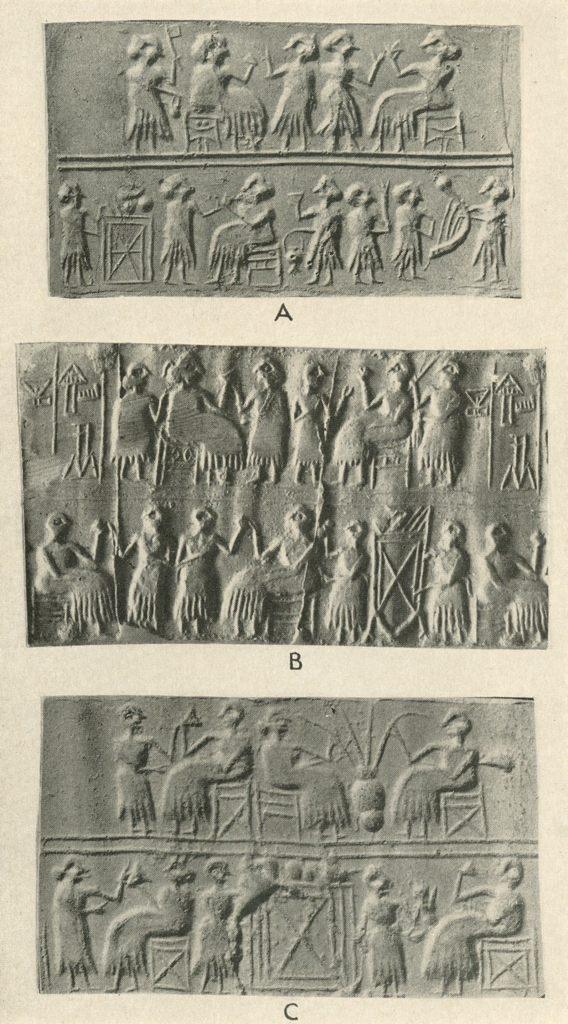

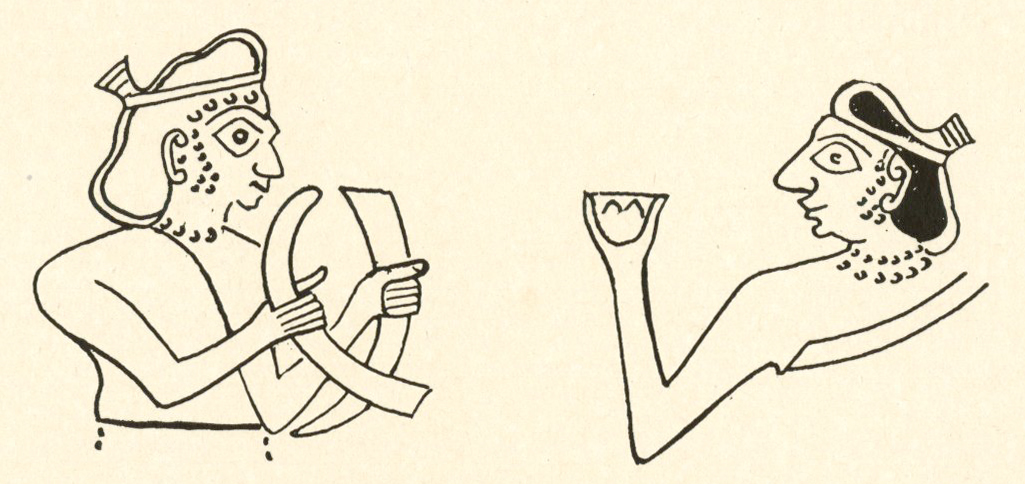

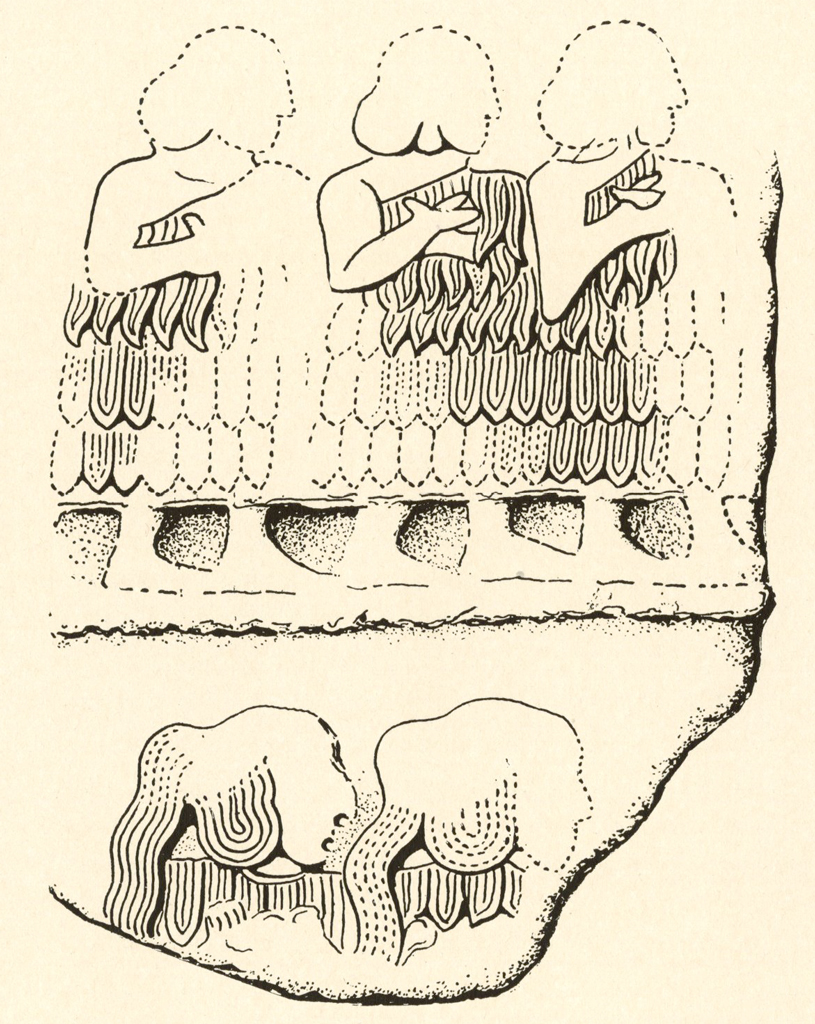

Fortunately we have more than one clue for solving such important questions. Among the best are the scenes engraved on her three blue lapis seals (Plate I), found lying with three gold pins on her right shoulder. Pins and seals served to attach her shawl after the manner of the fibulæ of more recent classical times. The largest seal (B) has given us her name inscribed in cuneiform characters : Shubad the Queen. The surface of the seal is divided into two registers. In the upper, the queen herself is seated on an elegant throne, and is attended by two servants. In her left hand she raises a cup, perhaps the fluted tumbler or the small oval bowl of gold found in her grave. A servant has filled it with wine poured from a silver jug. Opposite, on a throne of equal elegance, sits a male figure, who like the queen raises his cup before drinking. He is a person of importance. A servant attends him, jug and fan in hand, a lively touch of oriental luxury. He is probably the king and the high priest of the local god. His hair is short and his servants’ heads are entirely shaven, but the queen wears her hair tied in a heavy roll on the neck.

Museum Object Numbers: B16728

Image Number: 8648

The same scene is represented on the first seal Pl. I (A). The same servant holding a fan like a flag, of a type still used in the East, and a bowl hanging from a rope handle stands behind the king. Again the king wears his hair short and the queen a heavy roll tied and resting behind on her neck.

An interesting variant of the drinking scene is found on the third seal (C). Both the queen and her partner are using a reed, or long thin tube, to draw the liquid from the jar placed on a support between them. The beverage was probably a kind of beer, a fermented liquid with froth on the surface. Strainers of gold, silver, copper, or clay, show that the filtering of brews or mixtures was as common in that venerable antiquity as today. Four tubes rise from the vessel full of choice drink, two of which are for the king and queen, while two are destined for the other participants in what may be a ritual symposium. Four tubes of rich bejewelled material were found in the queen’s grave. One is a reed covered with thin gold, the others are of copper, plated with gold or covered with lapis, or with gold and lapis sections in alternating lengths. The pipes are three or four feet long with a short mouthpiece four to six inches in length, bent at right angles. A third person seated apart and attended by a servant raises a cup to his lips in the usual manner. The queen again wears her hair in a roll on the neck, while her companions are men with shaven heads.

A joyous banquet, the counterpart of the ritual symposium, is represented in the lower register of the three seals. A remarkable sideboard laden with bread, cups of wine, and pieces of meat, choice morsels, heads or legs, is the centre of the picture. Servants bustle about. The sideboard is a movable piece of furniture, like the one carried by the dog-butcher in one of the scenes decorating the king’s harp, a frame reinforced by crosspieces as on a throne or a chair. The queen’s sideboard rests on four elegant bull’s legs, probably of copper. In a religious ceremony the sideboard would be called an offering table. This Sumerian cane altar is found only on archaic seals of this time, so that it belongs only to the splendid period represented by the royal graves. It is replaced by a small altar with a ledge when new customs, perhaps new racial traditions, prevailed in the land.

On the seal bearing her name, the queen is not seated at the banquet, but the king, attended by a servant carrying jar and saucer, enjoys his cup with another companion. Both are shaven. On the second seal the queen is enjoying a little feast of her own, with music. She has called for her maids, her harp player, and her two singers. One brings a cup and a footed jar hanging from a rope handle. The harp player stands to play. His small semi-circular instrument has four strings and a metal knob. The singers clap their hands in cadence. The queen is faithful to her style of hairdressing.

Museum Object Numbers: B16693 / B16992 / B17709 / B17710 / B17711 / B17712

Image Number: 8316

On the third seal the king and queen are amicably seated at the same banquet, the queen with her heavy roll of hair tied behind while the king’s head is closely shaven. Sometimes the king wore a wig, sometimes even an artificial beard. Such a wig was the splendid golden one of Meskalamdug, which he assumed on solemn occasions and when he went to war. But in private life the king and his men showed their bald heads, a sensible custom in a hot climate. What a relief for him to take off his wig and enjoy a cup of wine in a cool, darkened room. Flints and copper razors by the dozen have been found in many tombs. The shaving of head and chin was not limited to the priestly or to the servant class. The king is attended by his cupbearer holding jug and saucer.

All three seals show the queen wearing her hair tied in a roll behind. Drinking a cup, seated at a banquet, listening to music or watching the dancers, she seems in a most human mood, enjoying the quiet evening hours. The scene is taken from private life, with nothing of the solemnity and religious meaning common on later seals. There are no shrines, no gods, no emblems in the field, no libations, no services of offering. The queen does not even wear the glorious golden crown and diadem or the golden comb which were deposited with her in the grave. At least the engraver did not try to represent them and was satisfied with the plain gold band which ties her hair. Nor does he place on her head that remarkable horned crown, the regular attribute of Babylonian gods of later centuries. Instead of a mitre we have the simple plain headdress; instead of libation and votive offerings, the joy of a cup and a solid banquet. In short, the worship of the gods after the fashion of a court and their anthropomorphic representation as kings and queens seated on thrones are not yet an institution. All scenes are borrowed from ordinary life and have a primitive simplicity void of all symbolism. The animals are real animals drawn by artists with the keen eye of a hunter for the graceful or terrible beasts of the field, like the lion, deer, and goat on the seal of King Lugalshagpadda.

But even the naïve charm of these banquets and drinking scenes is not without a deeper meaning. The milking scene of Al’Ubaid with its graphic details of cows and calves, pots and jars, the straining of the cream and the storing of the buttermilk, cannot be understood apart from the shrine of Ninkhursag, the mother goddess, protector of herds and pasture land. The kings and queens of Ur were high priests and high priestesses of the Moon God. Sisters and daughters of kings from Sargon to Nabonidus kept up the venerable tradition, and were thought to be the living personification on earth of the Moon Goddess. The banquet of the queen and her symposium have a ritual solemnity of their own, which gives full value to the rich equipment of gold and silver cups, drinking tubes, lamps, and jewels, and to her complete silver outfit of table, tumblers, jars, bowls, strainers, and wineskin. Raising a cup of wine is a rite which survives strangely in our modern toasts. It is a part of all libation services, the elevation of the holy grail. The sideboard laden with food and drink easily becomes an altar. The same cakes, pieces of meat, and cup of wine are deposited on the ledge altar in front of the divinity. But the scene, when the cane table disappears, takes on a more precise ritual meaning. The ledge altar of stone or clay is placed between the seated goddess and the priest. The goddess wears the horned crown, henceforth the indispensable attribute of divinity. The priest pours a libation into the cup. There is a crescent emblem in the sky. An assistant goddess in the background lifts her two hands, praying. The scene has become stereotyped and official. When and by whom the horned crown was introduced is still a very interesting problem. But it is clear at least that Queen Shubad took no delight in the mighty pair of horns which decorates the head of all the gods at the time of the first dynasty of Ur. The decorative motif of her comb, wreaths, and diadem is purely floral: beech leaves, willow leaves, pomegranate flowers, fruits in threes, buds and pods, palms, ears of corn, a comb spreading plumelike into digits tipped with seven lapis balls or seven golden flowers. The figures of animals in lapis, silver, and gold, which were used as decorative motifs, are pure animal forms. The ram, bull, deer, and antelope on the diadem, the fish and bull amulets, the monkey placed on the head of a pin, the donkey and the bull on rein-rings, the bulls and lions on the harps, thrones, and sledges are fine examples of realistic modelling. The characters of fable are still splendid animal figures. The imaginative mythology which gives them human attitudes is satisfied to give them also human hands only, or to hang a false beard from the nose of the bull. The man-headed bull and the scorpion-man point the way towards a new world of legendary creatures, half beasts, half men. But we are still far from the gods in human form, enthroned like kings and queens and worshipped in the style of a court. The high priest and the high priestess dressed in all their regalia and seated at their ritual banquet may have been prototypes of these.

Museum Object Numbers: B17063

Image Number: 8383

Music and dancing also have a ritual aspect. The harp roaring like a bull and the clang of cymbals accompanied the chanting of prayers in the Sumerian temples. The small harp was sufficient for the private chapel of the queen. The magnificent harps of gold and silver discovered of late in the royal tombs must have been used in official ceremonies, real oriental pageants where the ladies of the court, the dancers, and singers would appear with their gorgeous headdresses of golden leaves, combs, and beads. The cymbals of Shubad’s time were flat metal pieces straight or horn-shaped, which the dancers struck in cadence. They are seen in the hands of the kid dancing behind the scorpion-man; in the hands of a cymbal player on a gold cylinder seal of the high priestess buried in the domed vault discovered last winter; in the hands of a woman musician on the Kish inlaid plaques. Curiously enough the Museum has two such plates of copper brought from Fara thirty years ago, together with the well known bronze head of a goat with spiral horns. They are, most likely, Sumerian cymbals of Queen Shubad’s age. They are curved, thirty-five centimeters long, and four in width at the larger end.

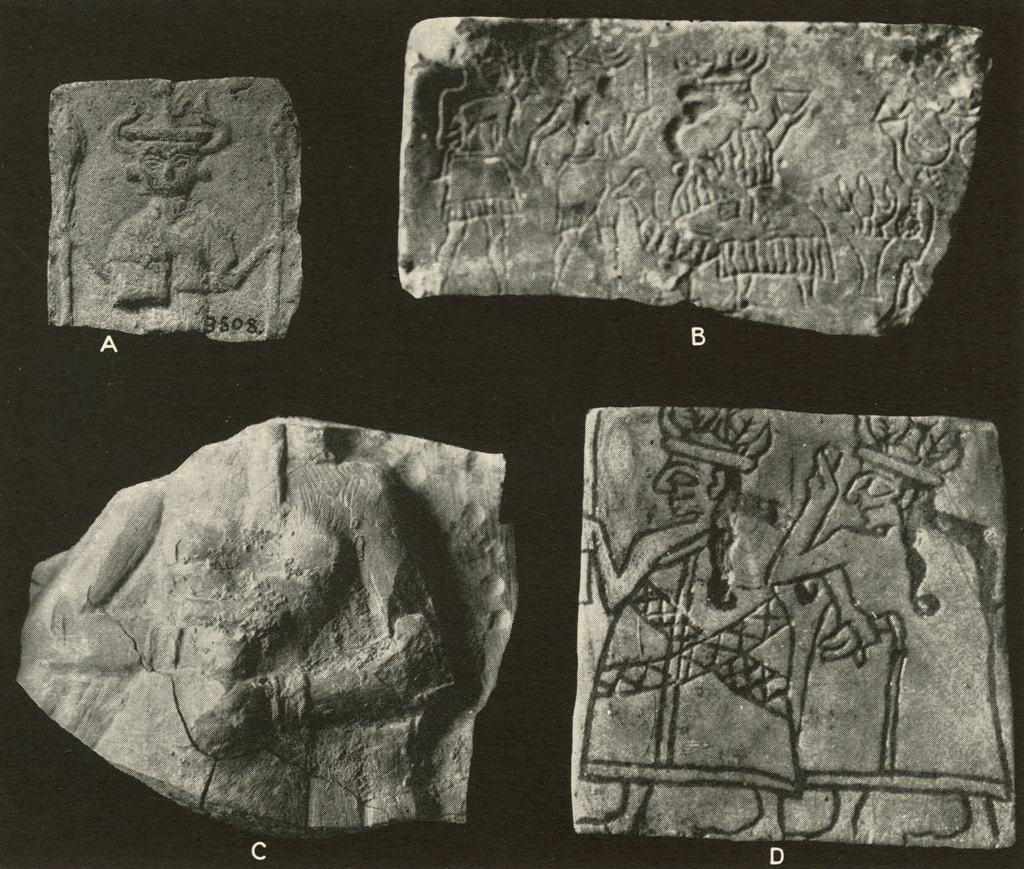

The ladies of Kish dressed their hair very much after the style of Queen Shubad on her seals. It is lifted from the shoulders, forming a heavy roll on the neck, is bound with a golden band passing over the forehead, and is twisted into a topknot on the crown. It is waved and curled over the eyebrows, and two small braids caressing the ears add an attractive charm. The large noses of the ladies, their prominent eyebrows, large almond eyes, and small, firm chins are decidedly oriental, but the rather heavy features are attenuated to more graceful type than that of the men. Their ears are not covered by any wig or ” bob ” after the fashion of Egypt. They wear one or two strings of beads round the neck. A shawl covers the left shoulder. One raises a fluted bowl, the other plays the cymbals or resonant plates (Plate X, A).

Museum Object Numbers: B16693 / B16992 / B17709 / B17710 / B17711 / B17712 / B17708

Image Number: 8369

At Kish roughly modelled figures of women decorate the flat spouts of clay vessels buried with the dead in the oldest cemetery. These are probably ritual vessels, known as Kish “granny vessels.” The figure has neither arms nor legs, but only a nose pinched up from the clay, two eyes and two breasts made of pellets of clay, and, in the more complete examples, a large triangular patch with incised markings for the pubes. Sometimes the figure is reduced to a couple of pellets and crossed incised lines. The spout is planted on the shoulder of the vase, and the bulbous part of the vessel may represent the rest of the feminine body. Such figures modelled and incised on a clay plaque are often called idols, though with no clear reason. Their association with the grave may give them a ritual meaning, common to funerals, the solemn passing of the dead into his house of eternity. The tombs were furnished according to the means and rank of the occupants. Royal persons took with them their guards, servants, singers, chambermaids, their chariots, harps, and gaming boards, their rich vessels and jewels, and a large provision of food and drink. The poor man had to be satisfied with less. The representation of the female body with direct and crude oriental realism, simply as a decoration of a jar of clear water, might, through its symbolism, satisfy his eternal thirst, better described in the style of the Arabian Nights. We need not see in these figures a mother goddess, an object of worship, but a practical means of satisfaction for the dead. Clay figurines, reliefs of the gods, or of the deceased worshipper before the shrine of his god, are found abundantly more than one thousand years later in the graves of the third Ur dynasty. But only the “granny vases ” in the early Kish cemetery suggest an analogy with the later practice. The rough clay figures modelled on the vases are purely natural and human like the scenes engraved on the seals of Queen Shubad. No symbolic meaning can be attached to them, any more than to the still earlier mud figurines of men, animals, sheep, goats, cattle, and dogs found in deeper levels. They are figures of a natural person or thing, a means of affecting the hidden spirit through its outside form.

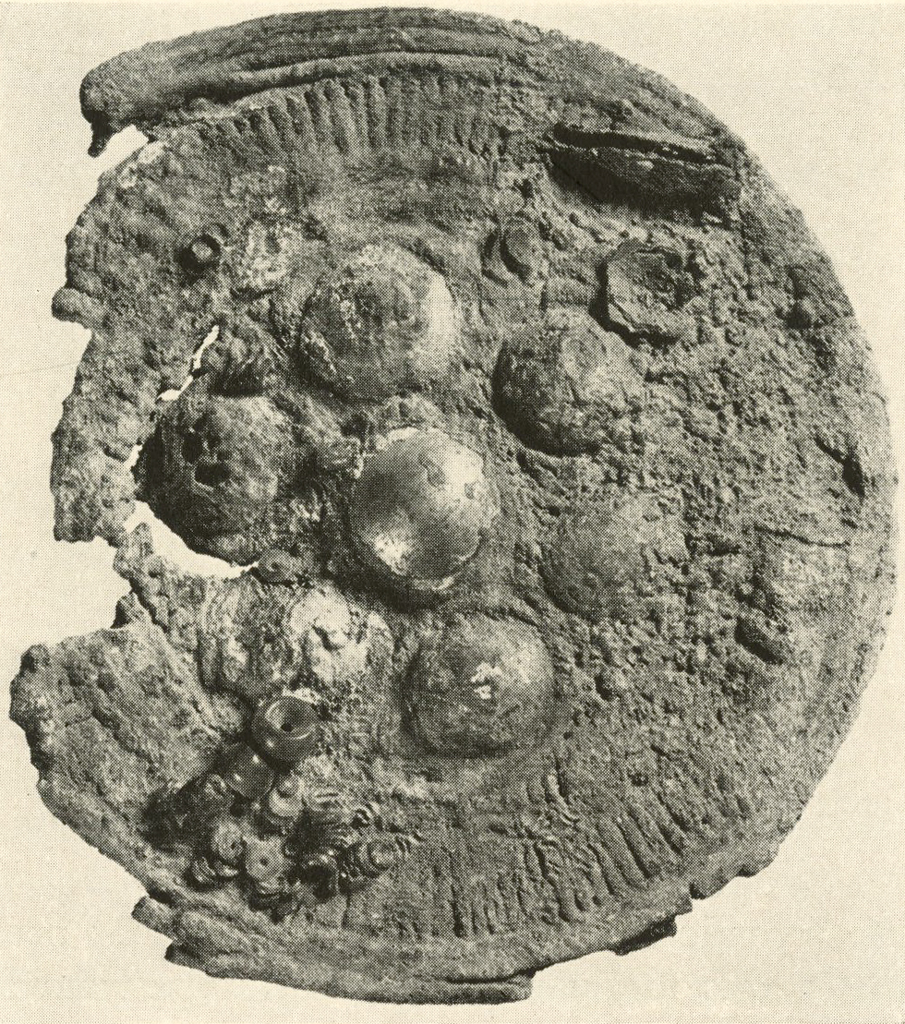

The “granny vase” found at Ur in grave 778 (Plate IX), not far from the royal tombs, shows that the practice was not limited to Kish. Still more interesting is another clay figurine roughly modelled by hand and planted on the shoulder of a jar like a spout. It is no longer a flattened tube but a real handle decorated with the head, breasts, and arms of a woman. She has the unmistakable attitude of the oriental Ishtar exposing herself which has been translated by the Greeks into the pudical Aphrodite. The style shows progress, but the inspiration is the same as in the Kish series. The nose is pinched up with the fingers out of the mass of clay. Eyes and breasts are added pellets. The hair of the head and of the pubes, the mouth, fingers, and necklace are marked by incisions. The figure has no legs, but rests on the shoulder of a jar, a fragment of which is seen behind the figure, with decorative markings in front of it (Plate IX).

Museum Object Number: B16726

Image Number: 8378

Her hair is tied after the fashion of the ladies of Kish, parted and waved, tied on the top of the crown and forming a roll on the neck. This is almost the style of Queen Shubad. The ears are visible; they are pierced to receive rings. She wears a dog-collar necklace. The ladies of the court at Ur preferred a tightly fitting necklace made of alternate triangles of gold and lapis with a wavy surface, and extraordinarily large gold earrings with crescent or lunate ends.

The fair ladies of Ur took pride in their hair. It might be worn simply floating on the shoulders, or hanging down the back, or parted and waved and bound with a crossband. They knew the allurement of locks and braids. Even when they tied it up in a roll they loved to let luxuriant curls play on the breast in front. Ishtar always had curls on her shoulders and curls lying on her breast. Little ” Mother Goose” insisted on two curls but the rest of her hair is tied in a dignified roll on the neck. On many later terra-cottas the young mother goddess or votary has “bouclettes” on her shoulders, but the ears are never hidden. The Museum has two charming examples of the type, a clay head modelled in the round and a small gold statuette which forms the head of a gold pin (p. 242).

When the hair was too long to be completely confined, it was allowed to flow freely over the band which pressed the roll down on to the neck. This slender curling end, which is visible on many seals and reliefs, sometimes takes on the proportions of a queue, distinguishing the daughters from the sons on a fragment of a stone votive plaque from Ur. A beautiful diorite head, on which all the details of waved hair, roll on the neck, band, and unconfined hair are quite distinct, shows that Shubad’s style survived for more than a thousand years. The head belongs to the British Museum and was found at Ur with the blue-eyed white marble head of the University Museum. A fragment of stone vase from Nippur shows a water nymph holding an overflowing ampulla. Her head, unfortunately broken, must have been turned sideways, and a heavy lock falls between the two breasts (C, Plate VIII).

But these heads and reliefs are comparatively late, dating from Gudea and the third dynasty of Ur. Monuments of the time of King Ur Nina of Lagash are more interesting because closer to the time of Shubad.

Museum Object Number: B16684

Image Number: 8365, 8366

Besides their long hair, tresses, and chignons, the ladies, enthroned or walking, wear crowns adorned with horns, feathers, plumes, or animal figures in relief, which compare with the crowns, diadems, and combs of Shubad and of her maids of honour. The gods and goddesses, distinguished by the horned mitre, are not unlike the high priestess and her votaries in their best attire. Old and well known reliefs from Nippur, Lagash, and Ur show how much they have in common.

In Figure D, Plate VIII, a priestess of high rank introduces a votary, whom she leads by the hand. Both have the same long hair falling down the back, with a loose lock in front, both wear the same interesting crown, both have the same type of Sumerian beauty marked by large noses, arched eyebrows, almond eyes, small chin, and a naïve smile. Both are dressed in a plain shawl passing over the left shoulder and decorated with a simple fringe. But the priestess-leader has tied about her waist a long embroidered belt or bejewelled stola, passing in a spiral around her body and crossed in front. She carries a sceptre in her right hand. Beneath a mass of beads which were found covering the upper part of the body of Queen Shubad, and which were of course unstrung and much disordered, there was about the waist an embroidered belt, the design of which could be made out. It consists of ten rows of bugle beads of gold, lapis, and carnelian, which were originally stitched on to some material, probably leather, with a row of at least twenty-nine large gold beads below. The belt did not completely encircle the body, the span being completed by strings of small lapis beads. Sceptres decorated with mosaic work of blue and white stone above and gold bands in relief below, were found this winter in the great four-chamber tomb, which was probably that of another royal priestess. The votary has neither sceptre nor belt but raises her right hand in what is clearly a ritual gesture, with the thumb crossing the four fingers on the palm of the hand.

Museum Object Number: B16753

Image Number: 8261

The band tied about the head of the priestess and of the votary, to keep their hair in order, becomes, through added ornaments, a fillet, a diadem, a crown, a mitre. Queen Shubad preferred a wide gold ribbon wound many times in a spiral about her luxuriant black hair. She used thirteen yards of the bright soft metal from two fifths to four fifths of an inch in width and weighing 1.04 lb. The end of the ribbon was bent over and soldered in a loop by which it was fastened with a pin to the mass of hair. A priestess and a votary, engraved on a small shell plaque from a deep level at Ur, both wear the horned mitre. Above the first band around the head and attached to it by two strands of ribbon a pair of bull’s horns, probably imitated in metal and joined in the form of a crescent, forms henceforth the accepted emblem of the gods and of their households. Between the horns, objects resembling feathers or palm branches may be the upper branches of a golden comb planted in the roll of hair. Shubad’s golden comb spreads into seven branches tipped with golden rosettes having centres of gold and lapis. These are linked together by a golden chain, and droop gracefully over the head. Her maids of honour wore silver combs having three points ending in flowerlike rosettes inlaid with gold, shell, and red stone. Others preferred silver combs spreading into five or seven points ending in balls of gold or lapis. Shubad sometimes changed her flower comb for a large golden triangular pin. The top of the pin is rolled over to form a tube in which feathers could be fixed. The ladies of the court were satisfied with silver pins of the same form. The queen’s gold pin lay beside her waist, together with another splendid diadem of gold and lapis.

On the horned mitre in Figure A, Plate VIII, the central piece of the comb is decorated with a bull’s head. The animal motif may be a symbol of the god of the silver crescent called the young bull of heaven, but it at once becomes the common property of all deities. The warrior goddess on a terra-cotta from Nippur holds up two lances with heads of an elegant leaf-shaped type, very much like the gold, silver, and copper spears of the royal tombs of Shubad’s time. They were mounted in an octagonal wooden shaft by means of a square tang secured with bitumen. Gold and silver bands decorate the shaft of the royal spears. Some have plain butts; in other cases the butt is of gold or silver with a projecting copper fork to engage the throwing thong, when fighting at a distance. The smith has put his mark on many of them, a bull’s leg, a jackal, or a bird. The soldiers of the guard had two spears apiece. Spears go in pairs. Our Sumerian Minerva holds two lances. She wears not a helmet but the horned mitre. The horns are attached not above but below the diadem, planted on each side of the head, probably meeting behind across the chignon. The comb has three feathers or palmettes on each side and a bull’s head in relief in the centre. The heavy ornaments are planted in the roll or mass of hair tied on the neck. Large earrings project below the horns. Shubad’s enormous golden earrings, eleven centimeters across and sixty ounces in weight, were attached under the gold ribbon in the hair. They have lunate ends, too large to be passed through the lobe of the ear. They were hung on the ear, not descending below the level of the jaw, framing the face like the large silver rings of modern Arab women. There were also earrings of gold, silver, or copper in the form of rings made of plain spiral coil, and pendants which were open rings with crescentic ends overlapping. Four spiral rings of gold of Queen Shubad were perhaps earrings. A dog-collar necklace made of gold and lapis triangles enclosed her neck. The warrior goddess wears a very closely fitting necklace. She has the Sumerian type of face with large nose, bushy, meeting eyebrows, almond eyes and small chin.

Museum Object Number: B3508 / L-29-346

Image Number: 9111, 6007

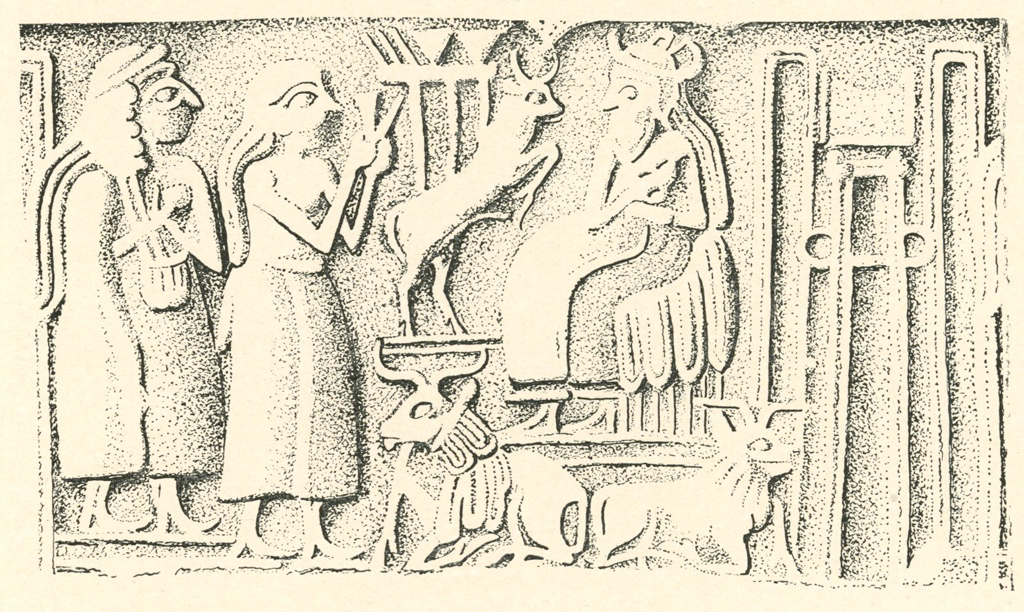

In Fig. B, Pl. X, the goddess of Lagash seated on an ancient Sumerian stool with rungs and drinking out of a fluted tumbler is a distant relative of Shubad and has inherited her beautiful cups. But she has adopted the horned mitre. Her hair falls loosely behind and in two tresses in front. It is waved and arranged in formal curls over the forehead. The points of the horns are much closer. The feather and plume decoration of the comb are somewhat indistinct. A servant, perhaps a nude priest, with a libation vase stands before her. Her husband the king is dispatching a prisoner by knocking him on the head with his big club. It is a speaking picture, the emblem of a protector of the city. He wears a false beard attached below his chin and perhaps a gold wig like that of Meskalamdug, with imitation of hair confined by a band. The prisoner, kneeling and handcuffed, is closely shaven and has the wound mark of the vanquished enemies which is seen on the inlay stela. This fragment of a limestone plaque with figures in low relief is one of the oldest sculptures from Lagash, anterior to King Ur Nina and close to the time of Shubad.

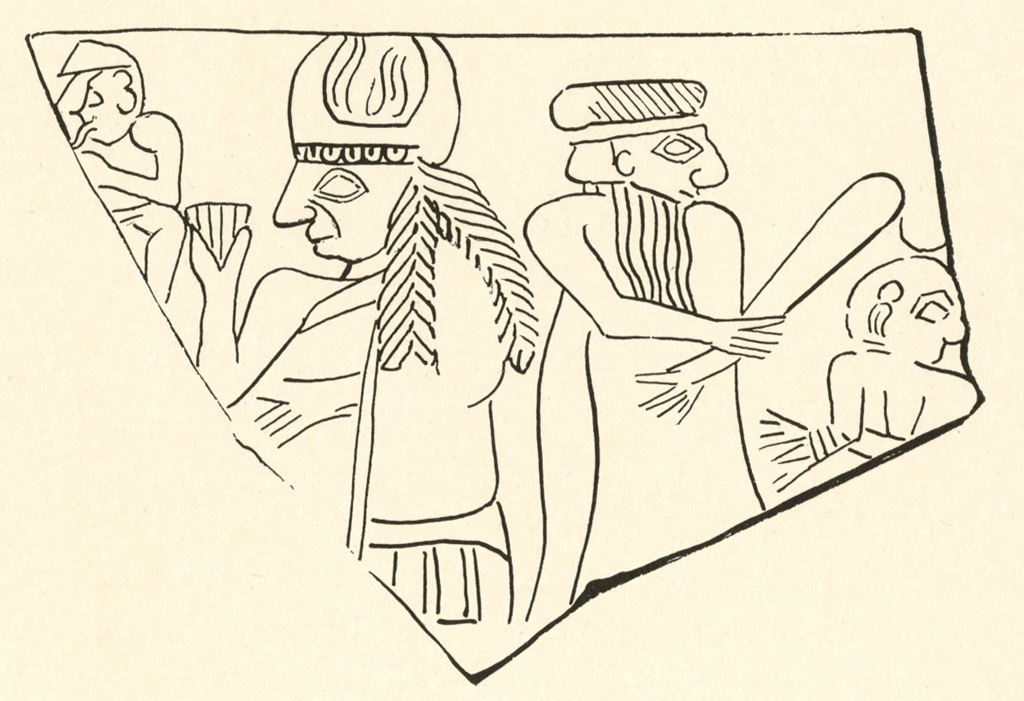

In Fig. B, Pl. VIII, the “Mother Goose” from Nippur on another fragment of limestone relief belongs to the same family of monuments. It was published years ago, but the new discoveries throw light on some of its details. The goddess is lifting the same ritual cup. Her throne is the symbolic goose. She holds in her right hand what looks like ears of corn or bunches of dates, but this may be simply a fly-whisk, to judge from a comparison with the object in the hands of the old Sumerian king on the engraved shell plaques which decorate a harp discovered last winter (Museum Journal, March, 1929, p. 28). She wears a gold band about her head, a heavy roll on the neck, a long tress down her back and formal curls above the forehead. Her comb is curiously like antlers with three tines on each side and a similar one is seen on the head of her husband, who is introducing the worshipper. Her long fleecy shawl of kaunakes modestly covers her left shoulder. Branches planted in a vase shaped like a small offering table stand before her, while the curious object beyond has been explained by Hilprecht as a lighted candlestick and by H. Schäfer as the representation of a nude woman seated with legs apart and arms erect, possibly in the pangs of childbirth. Most probably it is a candlestick or a ritual emblem, like that on the charming seal illustrated on Pl. XXXVI, 79, or on the engraved shell plaque published in the Museum Journal, June, 1927, p. 150. The nude libator holding a saucer and a jug with a spout stands in front of a high tripod, from which hangs the same curious band with two looped ends which decorates the Nippur candlestick. The same bull’s legs of copper support the shaft in both cases. They are found again on the seal as the support of a flag, and below the sideboard of Queen Shubad. The same looped band is thrown across a vase on which the nude libator pours water before the shrine of the Moon God (Museum Journal, September, 1926, p. 258). The looped ends here take the place of bunches of dates which in libation scenes usually hang on each side of a vase holding palms. Perhaps an older form of ritual is represented on this last limestone relief. It is remarkable that the vase is placed in front of a pile of sticks—the wood of the holocaust?—here and on the stela of the vultures and on another seal, Pl. XXXVI, 80, found in an early grave. But in the last two examples palms and bunches of dates are unmistakable. The right meaning of the looped band is still dubious.

Museum Object Numbers: B17249

Image Number: B17249

The crowned husband of the goose goddess acts as a verger, introducing the worshipper. The goddess turns her back on the scene, which lacks unity here and on the Lagash relief, forming a series of disconnected ritual actions. The king has long hair and a false beard after the old Sumerian fashion, from Kish to Nippur and Ur. He holds a sceptre, his staff of office. He and the shaven worshipper wear short fringed kilts. The offering is a kid or a young gazelle.

The ritual scene on a seal cylinder from Berlin (Bruno Meissner, Bab. u. Assyr., Bd. I), Plate XII is full of the same old Sumerian tradition. It is a complete picture of a libation before a shrine. The libator holding a vase with a spout before the enthroned god has long hair and a simple kilt closing in front. It is hard to decide whether we have a male or a female official of the temple, since entire nudity is no longer prescribed. The god and his worshipper both wear long hair falling down their backs. But the god has a false beard hung below his chin, while the smooth chin of the worshipper and the tresses falling on his shoulders are ambiguous. The long locks may be the formal headdress of a king or of a queen. Anyhow this important person stands one step higher than the libator. The object in his hands is not distinct, and leaves our curiosity unsatisfied. It may be a fluted bowl hanging from a rope handle, with a long spout, or perhaps a small hand harp.

The throne of the god, his headdress, furniture, and shrine are rich in details invaluable for a true reconstruction. A recessed gate leads to the throne room. Two posts bearing buckles decorate the outside. What is perhaps a curtain or a banderole hangs from the buckles. The tops of the posts end as the rounded heads of colossal clubs. Above the clubs a crescent-shaped panel between two projections of the towerlike gate forms a parapet breast high at the edge of the upper terrace. The throne inside is raised on a dais, with two crouching animals in front. These may be bulls or, more likely, goats, to judge from the tuft of beard, the hair on the neck, and the shape of the horns. The two prodromes of crouching rams cut in limestone, which were found four years ago inside the temple close to the Nebuchadnezzar gate, served the same purpose. The animals are represented in a familiar attitude with one fore leg raised, ready to rise from the ground. Back to back they form a well balanced group, in good Sumerian style.

The offering table, the old Sumerian cane altar decorated with the figure of a rampant bull in the round, is a most fascinating piece of furniture in the light of the latest discoveries. Pieces of bread—the shew-bread—and cups of wine, and the frame, if not the crosspieces, of the cane altar are familiar. Metal figures, bulls’ heads in gold and silver, bulls passant, and even stags rampant amidst bushes, are the magnificent ornaments of the royal harps. They were not known in connection with the cane altar. The figure on the seal may explain the two famous statuettes of goats rampant, found in January in a royal tomb, together with four harps, one wagon, and seventy-two bodies, among which thirty-four were those of court ladies with their headdresses of gold ribbons, wreaths, and silver combs, and their earrings and necklaces. The goats are twenty inches high, rearing up on their hind legs, with their fore legs caught in bushes, the stems, leaves, and flower rosettes of which are of gold. The fore legs are tied with silver bands. The heads and legs are of gold, the bellies of silver, the horns and shoulder hair of lapis, and the fleece of white shell, each tuft being cut separately. The same composition is found on many engraved plaques and strangely resembles the bull rampant on the Berlin seal. Bulls and goats stand on a small base, which in the Ur examples is a charming mosaic of checkerboard pattern. There are sockets above the figures of the goats, which proves that they formed part of a piece of furniture. The gold offering table in the very shrine of the god is preserved in the Hebrew tradition, and existed in the temple of Babylon in the days of Herodotus.

The enthroned god holds in his hands an indistinct object, cup, jar, or sceptre. Like the Moon God on the limestone relief (Museum Journal, September, 1926, p. 258), he has long hair and beard, long skirt, what is perhaps a shawl closing in front, and the primitive horned mitre, with one pair of horns and a plume. His throne with a concave seat and a small back is of the same style as the cane altar. A rich cloth of kaunakes, or perhaps a real fleece, covers it.

On a seal from Ur, Pl. XXXVI, 80, discovered not far from the royal graves, two worshippers approach another Sumerian deity of the same primitive type. An interesting vase of offerings is the centre of the picture, between the god and his servants. It is the familiar clay or alabaster vase with palms, branches, and bunches of dates, placed in front of a pile of sticks. The god holds a small bowl. The worshippers bring offerings. All wear the thick fleecy skirt. The throne is still of the old Sumerian cane type. The crescent of the new moon adds to the scene a ritual meaning.

The seal has two registers of figures, like many archaic seals. The lower scene, which represents the gathering of dates from the palm tree by two apparently nude figures, was long ago mistaken for a scene of paradise. Many religious feasts preserve the tradition of the offering of the first-fruits. The month of the date harvest was a great occasion in Southern Babylonian life. The fecundation of the palm tree had a ritual importance, and so had the cutting of the first clusters of ripe fruits. The gold saw was probably used for the purpose by Queen Shubad, when the silver crescent first appeared at the beginning of the season. A saw of the same form is still used by the natives, and was placed thousands of years ago in the hands of the Sun God, the great judge, the divider between light and darkness.

Also from the Ur cemetery, but of later date—the time of Gudea —comes a very interesting seal, Pl. XXXVI, 79, representing the offering of the first ears of corn to a god of vegetation. The seal is the property of Ursi, a servant of Enmenanna, probably a high priest of Ur, whose name was found engraved on a door socket in the shrine of the Moon Goddess (Ur Texts, No. 64). Ursi himself carries the traditional plough of Babylonia, which evidently existed long before Cassite times. It has two handles on either side of the ploughshare, to which is attached the curved pole with tackle for two yokes over two pairs of oxen. The title of Ursi is nigab, which means the opener, the ritual cutter of the first furrows. The high priest Enmenanna leads the procession, his staff of honour in his hands. He is followed by the high priestess carrying the ripe ears. A flag on a tripod resting on bull’s legs, flies the colours of the god, and marks the approach to the shrine. The god is distinguished by his sacred animal, a charming gazelle which has stopped behind the throne, and by his star on high. He may be Lugal-edin-na, the god of Eden, the fertile plain. He is dressed in the official style of his time. A shawl of kaunakes covers one of his shoulders. The three dignitaries have the long pleated linen garment which men wore fastened about the waist. It covers modestly one shoulder of the high priestess. The style of mitres and headdresses is remarkable. Four pairs of horns for the men and only one pair for the high priestess. The horned crown of the gods is probably borrowed from their human representatives. The hair of the enthroned god is tied in a heavy round mass with a projecting topknot after the style of the ladies of Kish. The same is true of the Moon God on the stela of Ur-Nammu. The male officials have a flat figure-eight roll of hair confined by a tight band. Graceful tresses fall down the back of the high priestess.

The many contemporary or slightly later evidences of Sumerian fashion in the time of Queen Shubad make possible the reconstruction of her headdress with fair certainty of truth. Hair and skull have disappeared, but the gold ribbons retained their position in the earth, and by lifting them without disturbing the strands outline and measurements were obtained. Mr. Woolley was led to assume “that the queen had a coiffure dressed over pads, the width across being no less than 0.38 m.”

“Bobbed” hair covering both ears was a charming Egyptian fashion, but one seldom seen in the Sumerian land, where custom left the ears more or less visible. The golden ribbons may have spread when the hair and skull collapsed. It is more likely that the heavy mass of hair was held against the back of the neck in a figure-eight by the golden ribbon which passed across the forehead, so that the larger diameter was originally from the front to the back of the head. We should expect a mass of hair fastened at the neck, since this would seem necessary to support a golden comb over one pound in weight. Thirteen yards of gold ribbon are not too much to secure the adjustment. One end—if not both—of the gold ribbon was rolled over and soldered into a loop to attach it firmly to the hair with a pin driven through. Two strands of the ribbon passing from the nape of the neck to the crown reinforced the edifice on very pure Greek lines. The small curls before the ears are like those of the ladies of Kish and the locks on the shoulders like those of many Ishtars; love goddesses and goose goddesses. The heavy gold earrings hang below the gold band, over the ear, and do not descend below the jaw. On many terra-cottas of later times they give a false appearance of ” bobbed ” hair. Probably a dog-collar of alternate triangles of gold and lapis was tightly fastened round the neck of the queen, like that worn by all the court ladies. The elements of it are found at the upper edge of the so-called cloak of beads. Other necklaces doubtless hung below in tiers.

Museum Object Number: B16744A

To mount the headdress and provide a realistic setting for the ornaments, the University Museum has had a head made on lines differing somewhat from the one so charmingly modelled by Mrs. Woolley. Even if we had the skull of Cleopatra, we should have little suspicion of her beauty and of the curve of the nose which turned the destinies of the Roman Empire. The work of the Greek artists and the reliefs of the queen on her coins are of great assistance, even if the result is beneath our expectation. The opinion of Sumerian sculptors working on living models among contemporaries merits consideration. Even if they had not the Greek ideal of a portrait and the subtle Greek power of expression, they were masters of their craft and could carve a statue in hard diorite. They could give it a likeness true to the general type if not to the peculiar characteristics of an individual. Their masculine type is attenuated into one of feminine beauty, which always has heavy eyebrows meeting over the nose and giving to the face strength and character. The nose is strong, nearly straight, and somewhat rounded at the tip. The eyes are large, almond shaped, slightly drawn up at the outer corners. The lips are well formed, not of the objectionable fleshy type. The chin is small, firm, and, in the model selected, protruding and marked by a dimple. This model is a little diorite statue of the Gudea time from Lagash now in the Louvre and called, from her headdress “la femme à l’écharpe.” She has the high cheek bones, large nose, and large eyes under powerful eyebrows of a true oriental beauty, and in spite of the sculptural effect of her staring eyes she possesses a charming queenly dignity.

Museum Object Number: B16770

Image Numbers: 8243b-8247b

Her eyes are shown as blue, for the reason that in many statues they are made of lapis lazuli inlaid in shell. We may enjoy the lapis blue, as the Sumerian artists did. It gives depth to her beauty. The mighty arc of her eyebrows was defined with black paint made of khol or stibium. Pots of this pigment have been found in many ladies’ graves. Calcite vases half empty show on the surface of the black cosmetic the prints of dainty fingers dipped in it centuries ago. The queen kept her kohl in a pair of silver cockleshells and in a charming semicircular toilet box of silver. The lid of the box is made of a piece of shell with animals in relief against a background of lapis lazuli. A powerful lion has thrown a ram down on its back and is biting its neck. The scene shows a keen observation of animal life and action and forms a well balanced group. The curve of the lion’s uplifted tail fills, by a happy inspiration, the semicircle of the lid. Blue lapis dots in a chain of engraved diamond pattern decorate the edge of the lid.

The gold chalice of the queen, modelled on very classical lines, is filled with a new cosmetic of turquoise blue colour. Perhaps the blue is not the original colour, which may have faded with age. But the analysis made by the chemical department proves that the queen’s cosmetic was really powdered turquoise mixed with traces of lead. Lead oxides vary from red to brown and yellow. Alloyed with the turquoise blue, they produce dark brown and purple shades of wonderful effect when applied to the eyelids. Very modern dolls must have heard of Queen Shubad’s cosmetic. Every court lady had some of the blue paint, a small mass between the two valves of a cockleshell. A pair of cockleshells may have the two cosmetics in one mass, half blue, half black.

The blue cosmetic of the queen filled not only her gold chalice but also a pair of cockleshells of gold and a pair of very large real cockleshells. It was tempting to use the royal blue in a reconstruction of her head. A streak of blue defining the eyelids is just as wonderful as the green malachite about the eyes of Egyptian beauties.

We may fancy the colour of the skin of the brunette queen to have been anything from dead white to golden brown. Her lips were the only red spot. If she used rouge it was made of hæmatite powder with traces of magnesite and phosphates from the clay with which it was mixed, as consistently found in examples from Ur and Nippur.

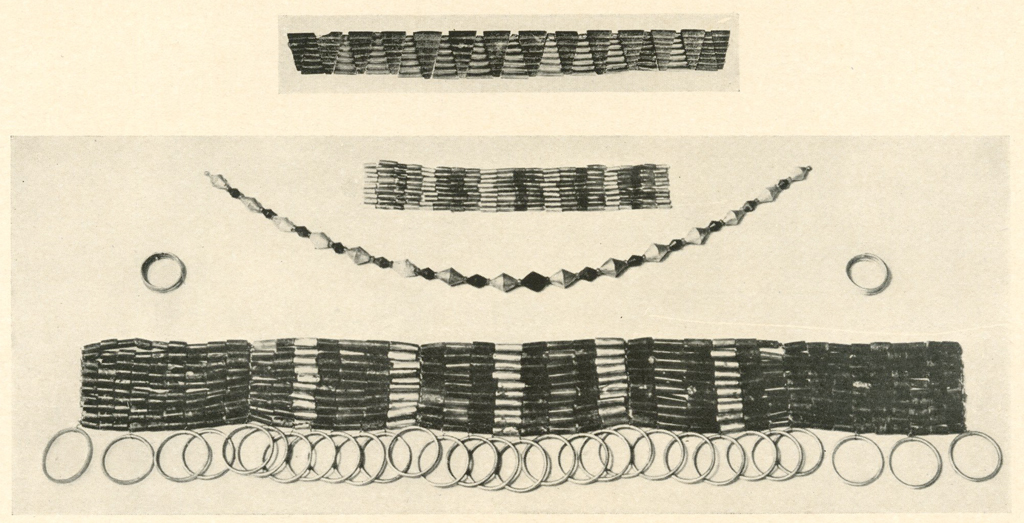

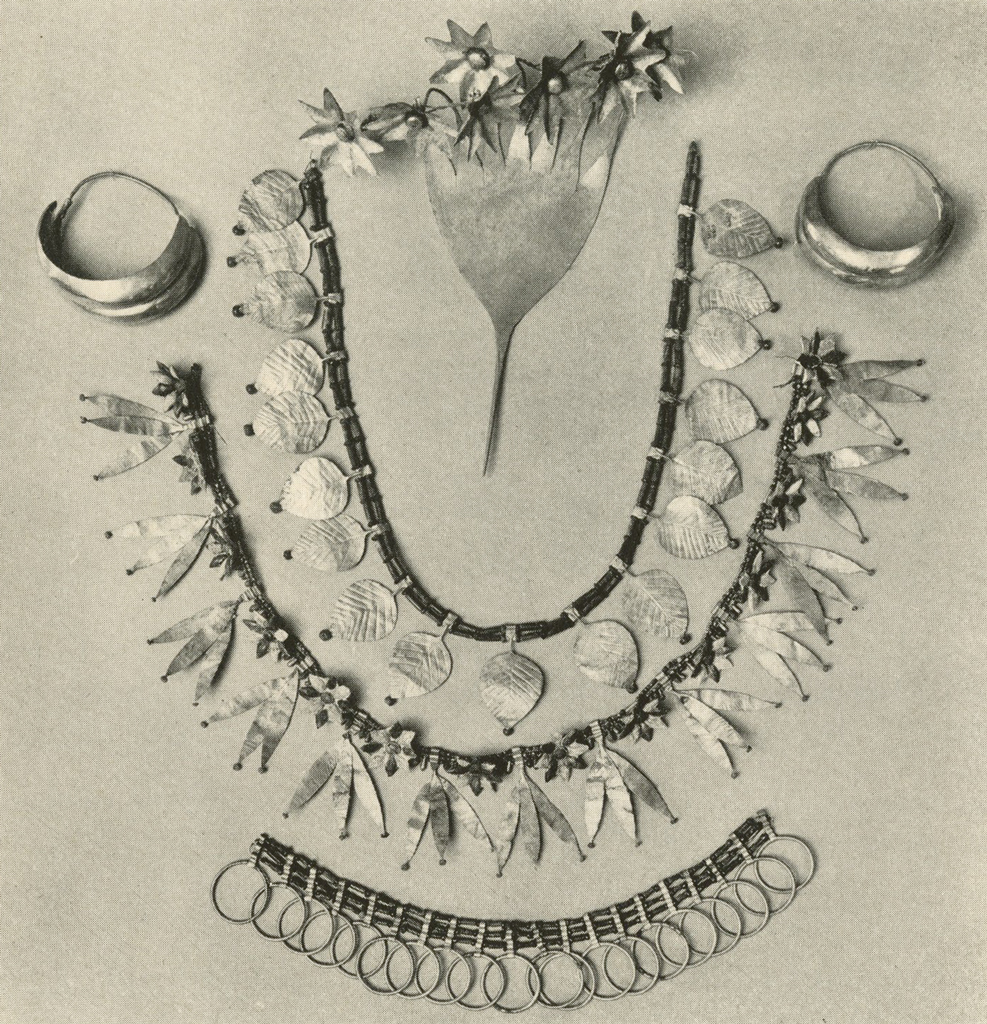

Golden wreaths added to the splendour of the queen’s headdress. The gold ribbon bound to the neck the heavy roll of hair and secured the edifice. Above this the golden comb spread its seven golden rosettes linked by a gold wire, their gold and lapis hearts nodding aloft. The golden earrings framed the face in their heavy double crescents. On the rigid lines of the ribbon the wreaths embroidered the delicate pattern of their ornaments. Four wreaths were placed upon the head of the queen. One is a mass of rings and beads. Twenty gold rings are mounted on three strings of lapis and carnelian by narrow strips of gold. The second has twenty birch leaves of gold attached to two strings of lapis and carnelian. The third is built on the same pattern, but the eighteen golden leaves are larger and are tipped with beads of carnelian. The weight of gold of the three wreaths is, respectively about 0.53, 0.44 and 0.375 lb. The fourth and most exquisite wreath is made of fourteen golden flowers with inlaid petals alternately of blue lapis and white paste, mounted on three strings of gold and lapis beads, with gold and lapis drops. Between the flowers are groups of three willow leaves of gold with carnelian tips. This wreath has been placed on her reconstructed head. It is hard to believe that she wore, when alive, the four at the same time. A queen has always more than one wreath, more than one necklace, more than one finger ring, more than one golden cup in reserve. A hairpin of triangular shape was found near her body and three golden pins on her shoulder. Another diadem of lapis beads and gold ornaments was folded by her side. Wreaths of golden leaves and wreaths of gold rings are found in many ladies’ graves and may have been worn in pairs or single above the golden ribbons. One wreath in a child’s grave was made of three strings of gold, lapis and carnelian beads, two gold roundels of wire filigree, and one large gold roundel of cloisonné.

Instead of a wreath, gold and silver plates and bands were sometimes worn on the forehead, attached with gold wire. They were of plain metal, or decorated with engraved or repoussé work, with a star rosette in relief, or with rows of human and animal figures in intaglio. The thin elliptical gold plates were not used as they were in Egypt to seal the lips of the dead. Six golden frontlets were found round one head, and a golden band was still adhering to a broken skull.

The diadem of Queen Shubad is a marvel of delicate work. It consists of a thousand minute lapis beads, which were probably mounted on white leather, and of a profusion of gold ornaments attached by silver wires to the blue background. Among them are four pairs of animals couchant: two rams, two antlered stags, two gazelles, two bearded bulls, disposed amidst ears of corn in gold; bunches of pomegranates with three fruits tipped with carnelian and three golden leaves; shrubs made of gnarled stems of gold plated with silver and having fruits of gold, lapis, and carnelian; finally, palmettes of gold wire. Two other diadems made of golden figures over a bitumen core, pomegranates and animals, gold rosettes and leaves, and palmettes of silver wires, belonged to ladies of quality, perhaps to high priestesses.

Below her dog-collar of gold and lapis triangles, Queen Shubad wore another collar of small gold and lapis beads with a pendant, and a rosette of gold in the form of a wheel in which the open work is filled with lapis—not with carnelian. Strings of beads of gold, silver, lapis, carnelian, agate, later of jasper, chalcedony, sard, of copper gilt, beads large and very small, solid, or hollow and filled with bitumen, round, long, lentoid and conoid beads of every shape, form, and colour, have been found in every grave, and were apparently worn by both sexes. But where high officials were satisfied with three large lentoid beads of gold and lapis hung about the neck on gold chains, or worn as bracelets, sometimes with carnelian spacers between the stones, the queen and the ladies of the court were never tired of new styles, new colours, and new forms, and carried their treasury of beads with them into the grave. Beads furnish rich and attractive matter for a more complete survey of ladies’ adornment in the past. The upper part of the queen’s body was found covered with a mass of beads, of course all loose and much disordered; but in spite of the breaking of the copper wires they lay in tolerably good order, and the arrangement was noted for restoration. They were mostly beads of gold—some adorned with applied filigree—but also of beautiful choice carnelian and banded agate, of lapis, and of silver.

It was at first thought that this mass of material should be constructed as a beaded cloak composed of vertical strings of mixed beads arbitrarily arranged between a fringe at the bottom and an open-work collar above. The cloak was thought to open on the right, and the solid edge to be embroidered with small carnelian beads. Three gold pins and three cylinder seals fastened the heavy mass on the right shoulder, besides a number of amulets and pendants.

Museum Object Number: B15241

Image Number: 8849a

If, however, instead of a cloak, the body of the queen was covered with a mass of disrupted necklaces, it is easier to understand the reason for the use of selected and graded beads of one type of banded agate, of others of a specially beautiful red carnelian, and of four strings of long gold filigree beads, which clash when lined up, with heavy gold or lapis conoids. Also the good taste of other jewels, rings, wreaths and combs, seems to protest against the disposition of mixed beads arbitrarily arranged in vertical strings. Necklaces hang in natural curves round the neck. Like the gold ribbons, they would have been deformed by the collapsing of the body in the grave.

It now seems wise to believe that the fringe referred to above was in fact a belt: ten rows of bugle beads of gold, lapis, and carnelian, and a row of twenty-nine gold rings below, sewn on some material which has disintegrated, and continued round the body by strings of small lapis beads; and that the collar was a separate unit made of lapis and gold triangles—the usual elements of the tightly fitting dog-collar, but here separated by gold beads, with small bugles sewn on horizontally below.

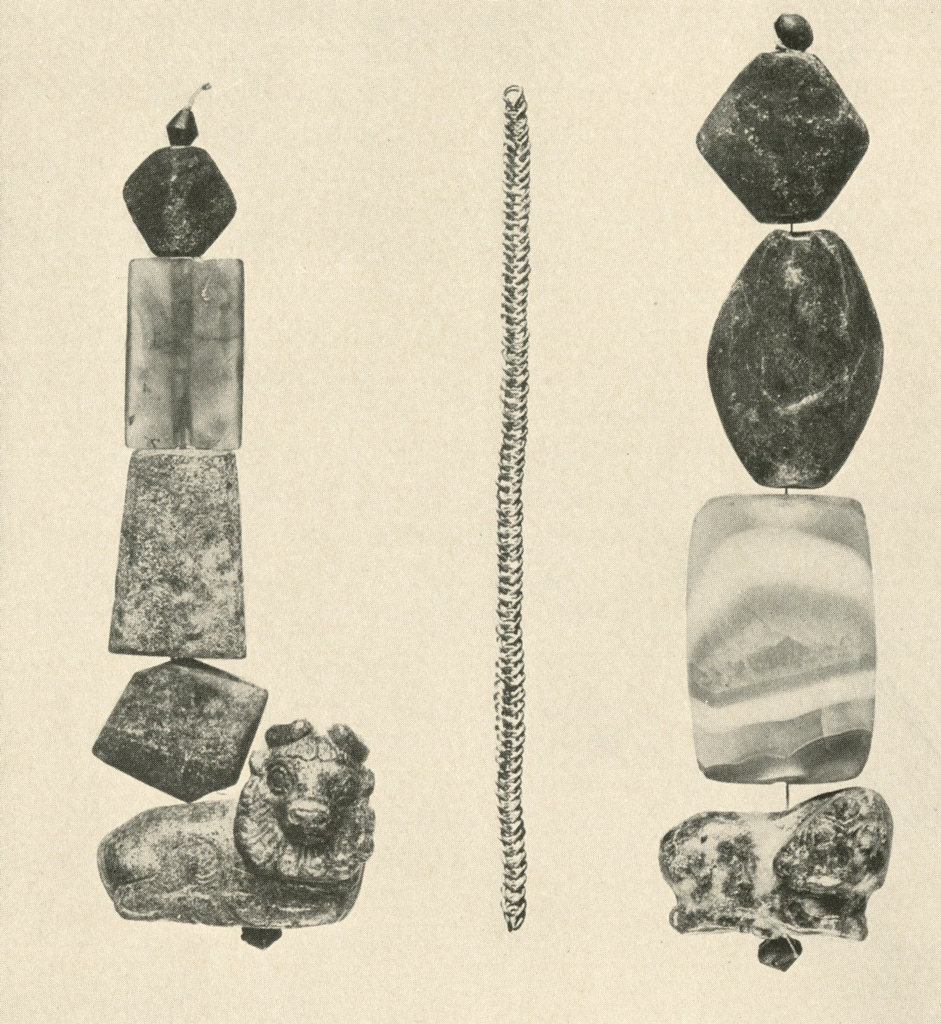

Precious amulets have been found in other graves, a gold bull with a false beard, a bird of gold with a lapis tail, a golden bird on a fruit. In the tomb of King Meskalamdug a lapis frog and a lapis ram; in a Sargonid grave, a goat rampant of gold hanging on a string of beads. Queen Shubad had the largest collection of all: two fishes of gold and one of lapis, a group of gazelles, seated back to back, found by her elbow, and by her shoulders a reclining calf and a bearded bull of lapis with a false beard attached by a string over the nose. Each of these last figures is hung on a short string of large agate, lapis, and carnelian beads.

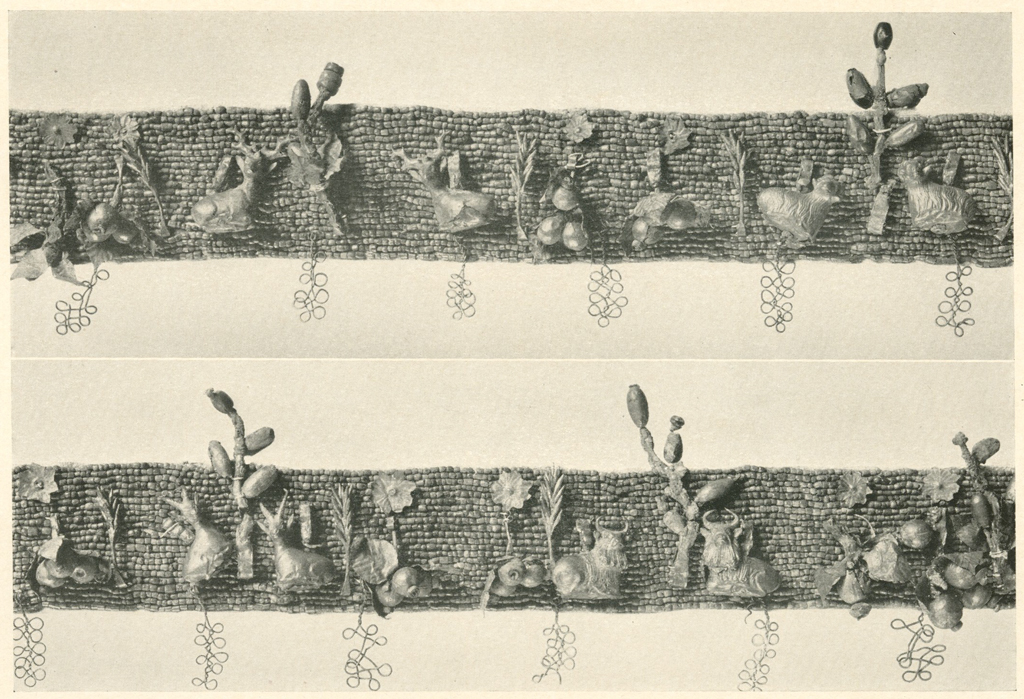

Pendants were made of cloisonné work of gold, inlaid with stones and with filigree of gold in the form of large roundels. Big round buckles of silver filigree were used to secure a cloak. The finger rings of gold, silver or copper were generally a spiral coil of fairly thick wire. Out of ten gold rings of Queen Shubad seven are made of a square wire twisted and coiled in spiral with cable effect between two ends of plain wire; one has a border inlaid with lapis; and two are of cloisonné work inlaid with lapis. Larger coil rings of silver and gold are probably toe rings. Metal bracelets are plain bangles of gold, silver, and copper. The queen may have toyed with the sceptre beautifully decorated with gold bands in relief and inlaid mosaic, and with the fly-whisk handle checkered in black stone and white shell. We like to imagine her twisting in her fingers the silver spindle with the slightly convex lapis head—the silver shaft is still 16 cm. long—or the mother-of-pearl handle, decorated with a little lion in the round, which was probably fixed by three rivets to a palm leaf fan. She may have used the gold chisels, like the gold saw, for some ritual action, breaking a seal or tracing the first lines of a relief or of an inscription. She probably trimmed the large silver lamps which continued to light her grave as they had lighted her nights. Her little silver lamp, copied on a cockleshell cut in half, was close to her hand. The king had his gold lamp with his name engraved on it. Fair ladies preferred a lamp of translucent alabaster with a beautiful relief : a man-headed bearded bull, couchant. Many a time the queen moved the pieces on the magnificent gaming boards of silver, lapis, and shell, admiring the animal figures so cleverly designed by the court engraver, while her servants played on the harp and recited the heroic deeds of Gilgamesh, or the love affairs of the Queen of Heaven. Out of her wardrobe, the keeper of the wardrobe would bring pure pleated linen tunics, white or purple shawls with fringes or embroideries, or the supple and warm kaunakes with its fleecy face. But the fine garments have long perished. Even the wooden chest in which they were preserved, probably of cedar wood, has turned to dust, leaving in the ground its mosaic border and its decoration of shell figures on a mosaic background.

But out of the dust archæology has brought forth a treasury of knowledge, beauty, and human interest, of which the Director of the Expedition, Mr. Woolley, and the two Museums supporting it feel very proud. Henceforth we shall have a new by-word of ancient history: In the days of Queen Shubad.