IN the year 1595, the Spanish admiral, Alvaro de Mendaña, sailing westward from Peru in command of an expedition sent out by the Viceroy, Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza, Marques de Cañete, discovered a group of islands lying about midway between the Peruvian coast and the great island of New Guinea on the western verge of southern Pacific waters. The name which he gave to the islands in honor of his patron the viceroy has survived in shortened form as Marquesas Islands. Nearly two hundred years passed before another European ship, Captain Cook’s Resolution, dropped anchor in Mendañas harbor in the island of Tahuata, which the Spanish explorer had named Santa Christina. Both of these voyagers visited only the southern part of the archipelago. The northern islands, including Nukahiva, the largest of all the twelve islands in the two groups, were discovered by the American Captain Ingraham in 1791. Another American visitor, Captain Roberts, who arrived two years later, named these the Washington Islands. The islands of both groups are now usually known collectively by the name Mendaña gave to the southern archipelago.

Museum Object Number: P2159

Image Number: 113

They are of volcanic origin, lofty and rugged. In most cases there is a high central ridge buttressed on both sides by others less lofty enclosing between them parallel deep valleys opening on the sea. The inhabitants of each valley, the lower, seaward portion of which contains the only fertile ground, were constantly at war with their neighbors. Their inveterate feuds, resulting in frequent raids rather than pitched battles, produced a not inconsiderable portion of the food supply; for the Marquesans, before the pacification of the islands by the French following the hoisting of the tricolor in 1842, were incorrigible cannibals. To this fact, as will be seen, not a few of the objects from the Marquesas contained in the University Museum’s collection, and illustrated here, bear witness.

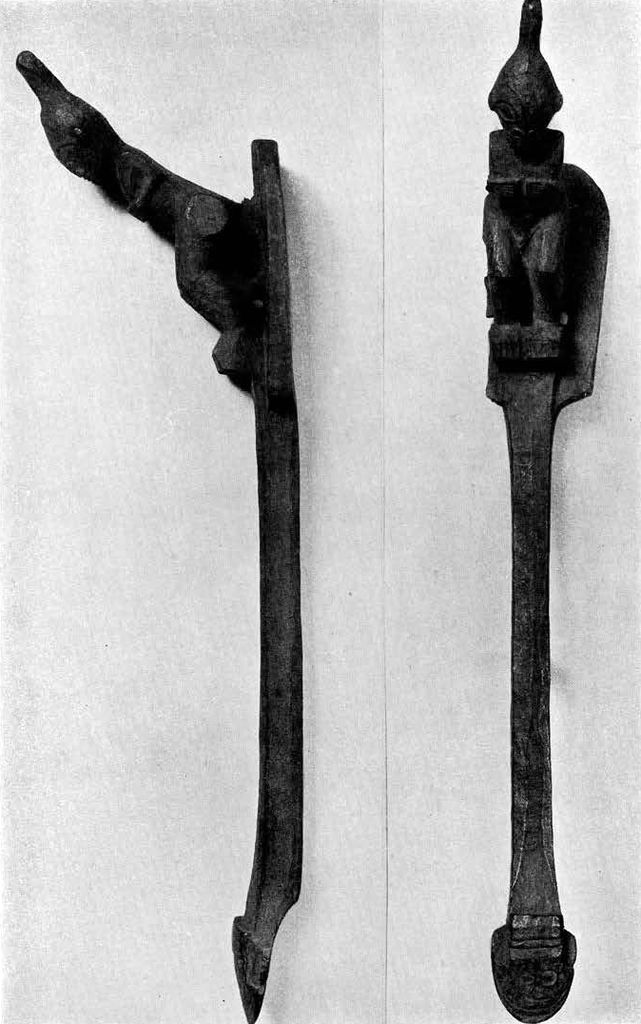

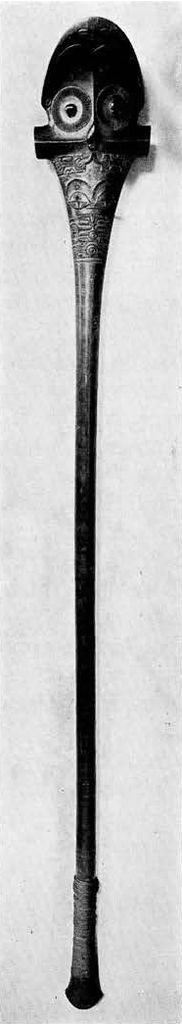

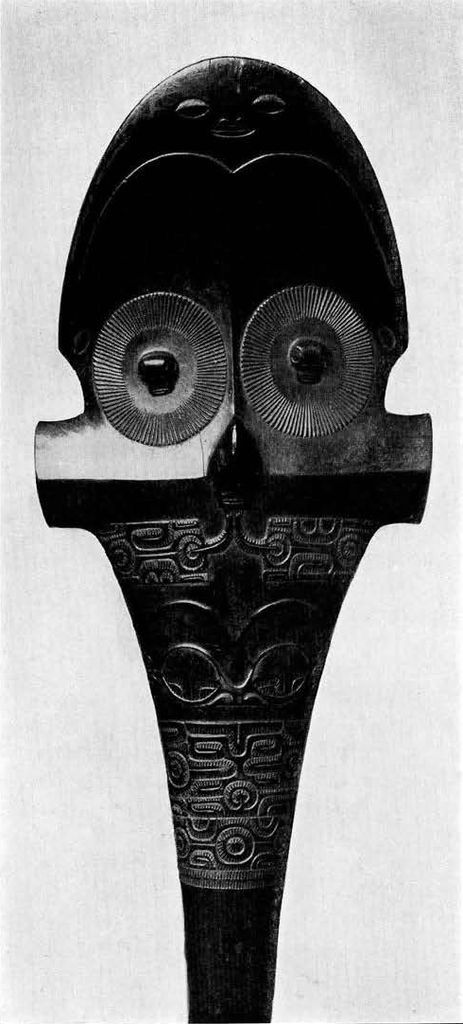

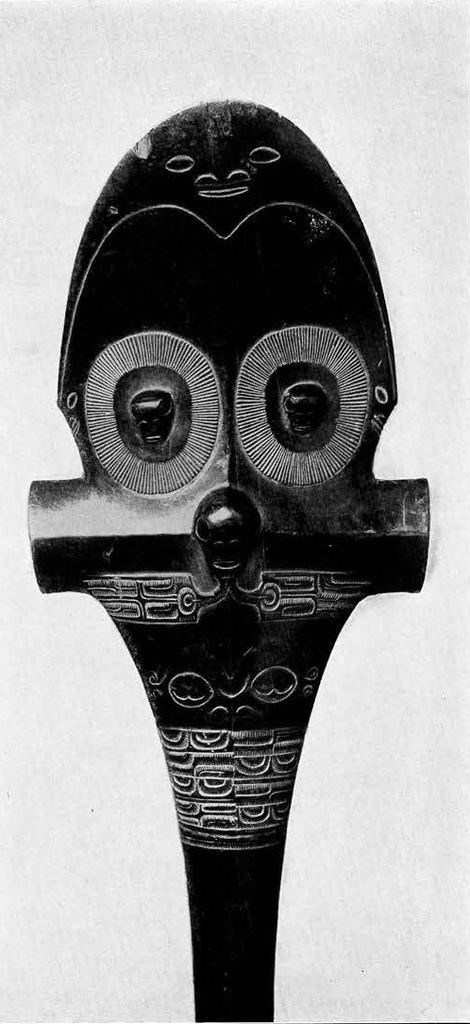

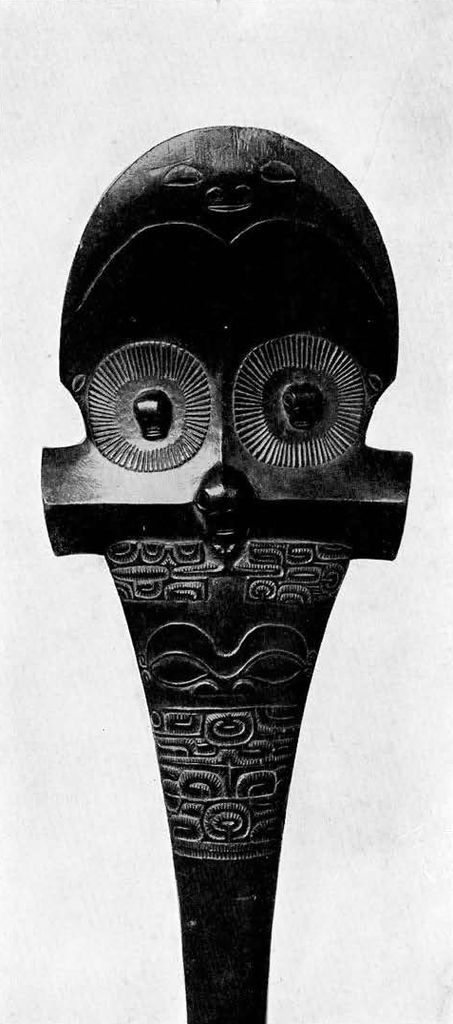

The early visitors to the islands speak with one voice of admiration of the fine physical proportions of the Marquesan warriors, and it is not difficult to believe that they must have had considerable muscular force at their command. The war clubs which the warriors carried into battle (Figs. 78-82) were made of the exceedingly hard and heavy wood of the toa, ironwood or casuarina. They were about five feet in length, topheavy with their massive heads and slender, tapering shafts, and must have required considerable strength and staying power to wield freely for attack or defense. This type of club suggests by its general outline a possible development from the paddle, which, in fact, in those seas, is a common weapon of hostile landing parties met by opponents on the beach. On this supposition it would be difficult, however, to account for the strongly marked transverse limb which divides the head of the club into two well defined parts, providing two distinct areas of ornament, which are, however, linked, as will be seen below, by a common feature of the whole plan of decoration. This plan is marked by three characteristic motifs. Primarily, the whole head of the club is treated as a human head. On this the eyeballs and nose are indicated by miniature representations of other heads in prominent relief, and the mouth, below the transverse limb, by a grouping of the ears, eyes, and nose of another face made into a single unit of the whole scheme by a singularly skilful combination of graceful curves flowing into one another, the coalescence being assisted by the extreme lowness of the relief. Next, by an extension of this principle of repetition in petto of the chief motif, but without its application to the representation of essential features, other small faces are placed at three different points on the periphery of the upper part of the head of the club—at the top and in the notch at each side immediately above the ends of the transverse limb. Each of the last two appears half on either side of the sharp edge to which the sides of the club are here pared down, and is thus turned in a direction at right angles to that in which the other heads look out (Fig. 82). Finally, there are two bands of conventional decoration below the crosspiece and separated by the composite mouth detail described above. The two broad sides of the club head differ only in the arrangement of the details of these bands, the chief elements of the ornament being in general the same—circles or ovals, sometimes open, or segments of these, combined with oblong figures and incomplete scrolls. These elements, or portions of them, sometimes appear within the inner oval of the large eyes between the two bands (Fig. 79). All these details are very lightly incised. They are reproductions of similar designs which the Marquesans tattooed upon their bodies. Undoubtedly they are symbolic; it has even been supposed that they are of the nature of hieroglyphs. But we have not the key to their meaning, and the possibility of its complete recovery is slight. Of such clues to their meaning as remain, one may be mentioned here.

Museum Object Number: P2159

Image Number: 114

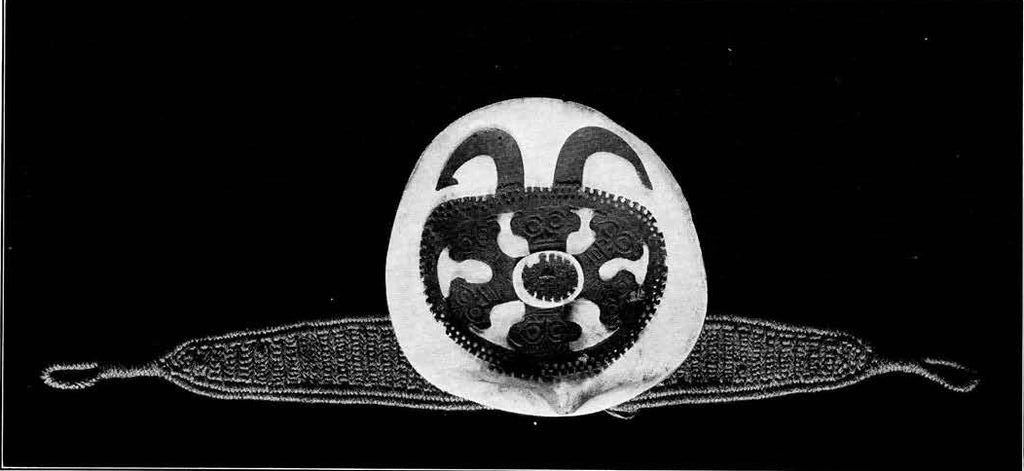

The fillets worn by Marquesan warriors were ornamented with one or more discs of haliotis shell. To these discs were applied others of tortoiseshell, smaller, and decorated a. jour with various designs. Sometimes two large hooks also of tortoiseshell projected from the rim of the latter (Fig. 83). We are told that these hooks are also represented in the conventional ornament of the clubs, and were tattooed on the neck of the avenger of blood. In some cases this representation is obvious enough. In the specimens illustrated here it probably appears in some of the scroll like details of the lower part of the club heads.

We know the significance of this hook, the badge of the warrior. It was a threat to the enemy, a reminder of the unseemly and terrible fate that awaited the vanquished. It was the symbol of the rite of human sacrifice performed at celebrations of victories and on various other occasions, such as the death of certain priests, when a god had to be propitiated or when formal thankoffering was due. From the bough of a great tree within the moraï or sacred enclosure the victim was suspended by his mouth from the prototype of this symbolic hook.

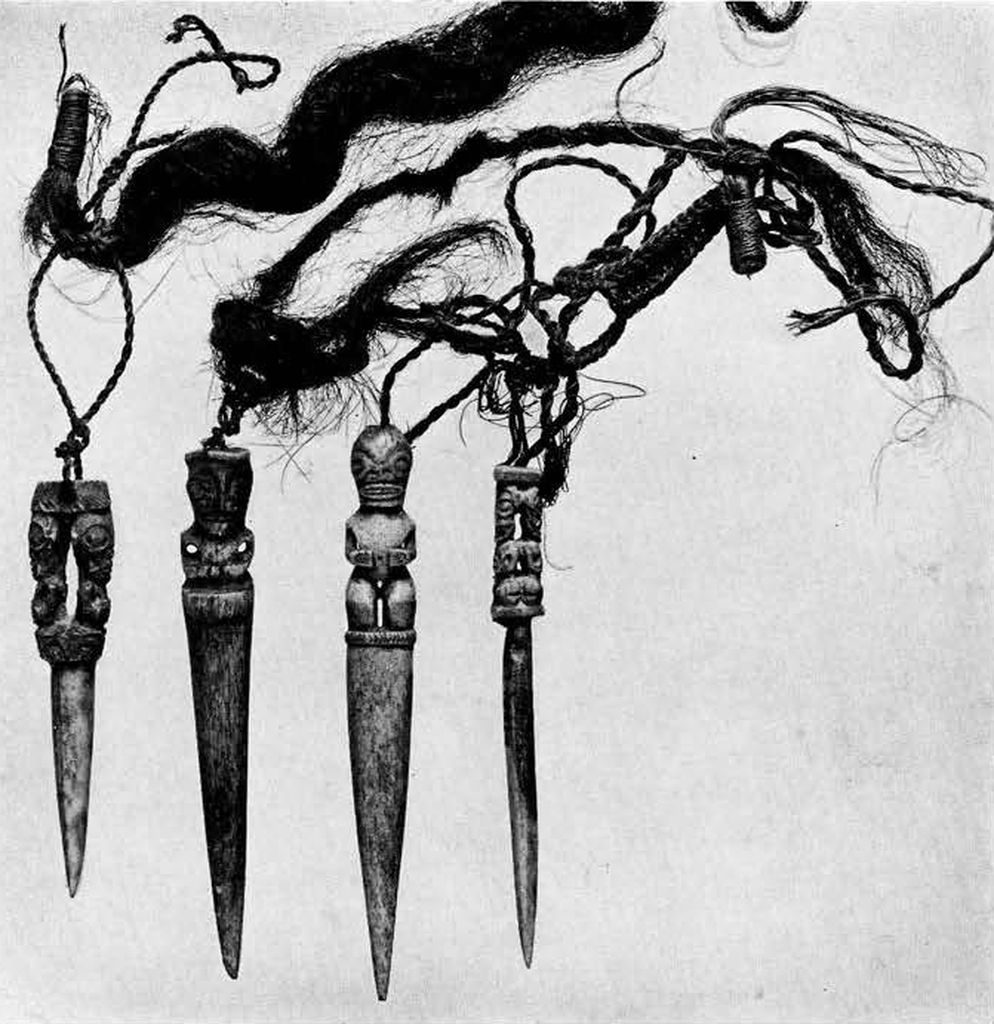

A wrapping of cord made of the fibre of coconuts attaches to the handle of another Marquesan club in the Museum collection a number of strands of human hair, a further indication of the relation between war and the food supply of gods and men. Human hair was employed by the Marquesans, however, for various purposes of personal decoration not always necessarily related to these ceremonial practices, except in so far as the practices represented the, at least partial, source of the supply of hair. Men of rank wore capes, short kilts, armlets, and anklets made by attaching locks of hair to cords by which these ornaments were fastened about their bodies and limbs.

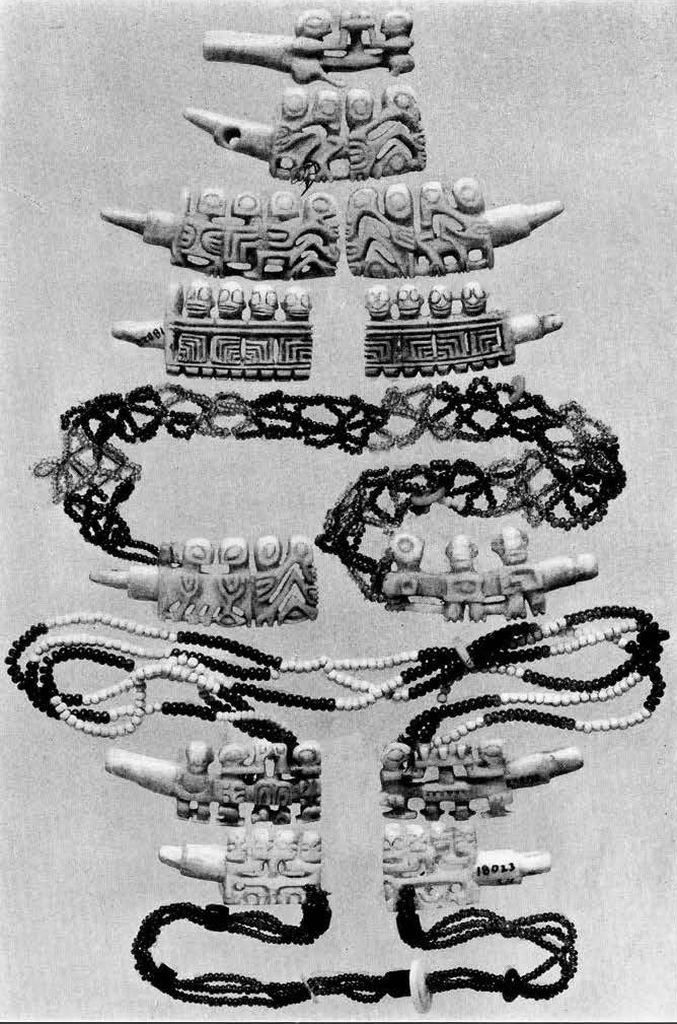

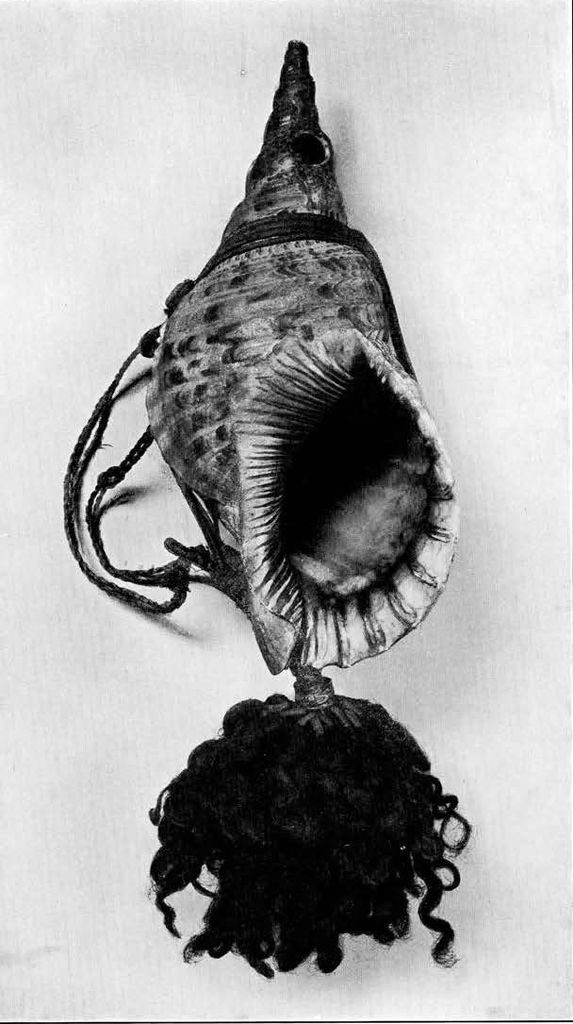

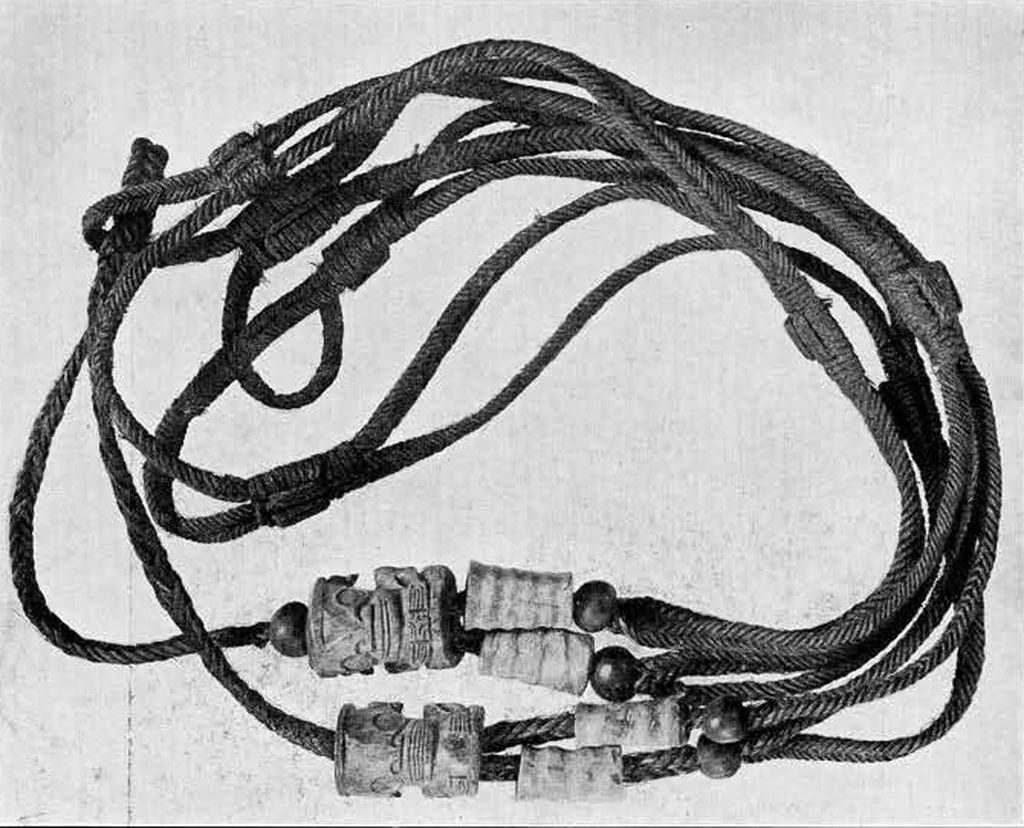

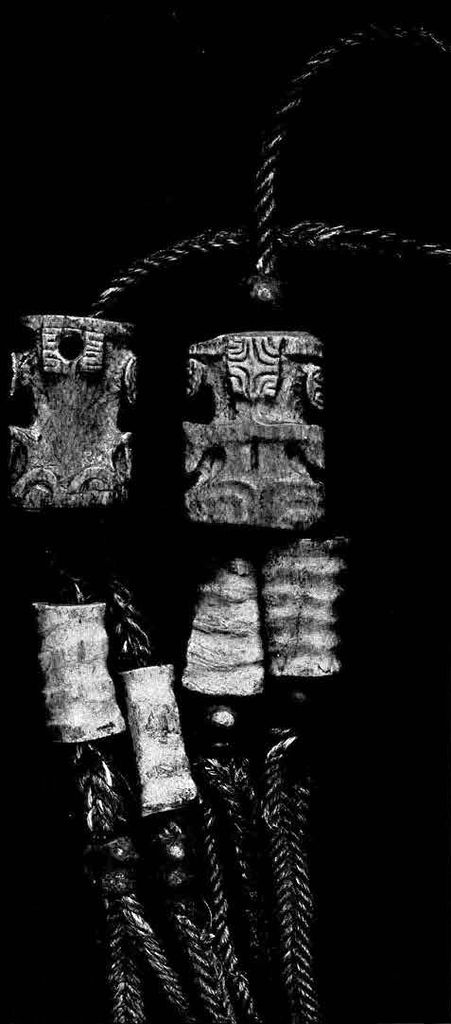

From the bones of the victims were fashioned various articles, the employment of which combined magical with ornamental and practical purposes. Such were the carved bone rings through which were sometimes passed tresses of hair (Figs. 84-86). It has been stated that these were occasionally worn merely as ornaments by the men, and that the tresses were taken from the heads of their wives. But they had not always so innocent an implication; sometimes, at least, they were worn by the avenger of blood, in order that he might constantly be reminded of the vengeance he was sworn to take. The rings were also attached to the conch shells which served as war trumpets. In this case, too, they were associated with the clustering locks of hair with which the trumpets were decorated (Figs. 87-89). The plaited cord of which is formed the gourd sling (Figs. 90, 91) passes through two of these rings. Slenderer rings of bone or whale ivory, corrugated, are found on the cords of this and on the amulet, Fig. 86.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-16

Image Number: 117

Plaited strands of hair formed into a ball surmount the wand (Fig. 92) which was carried by a chief on occasions of ceremony , the symbol of his rank or the mark of authority. Below the ball the staff is encircled by a short tube of woven fibre. This is decorated with a design formed by weaving hairs into the fabric. In the example pictured here the chief feature of the design is a lizard ; in other cases it is a human figure, or there may be nothing but the chequer pattern which is secondary in this specimen. In various parts of Polynesia lizards are regarded as symbols or incarnations of divinity, or as the hosts of spirits of the departed. Since chiefs partook by inheritance of the nature of divinities, the lizard would be a fitting symbol of their power.

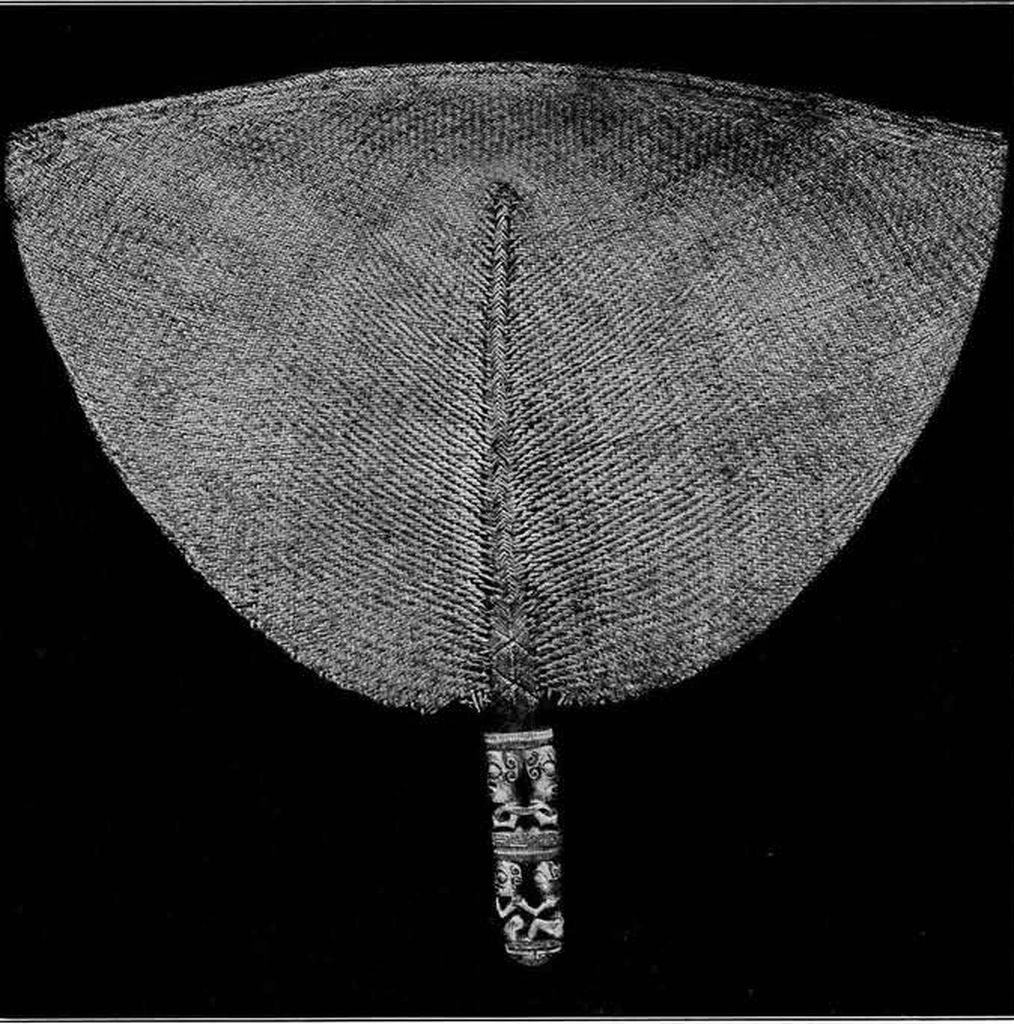

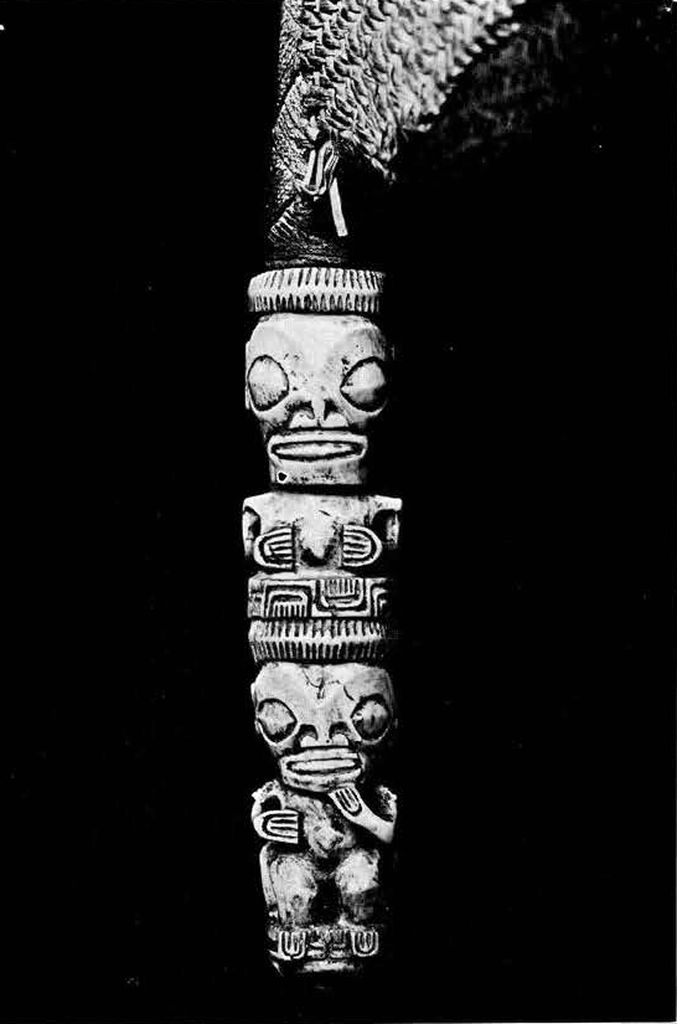

Of bone and of whale ivory, as well as of wood, were made the richly carved handles of the fans which were carried by people of rank (Figs. 93-101). The small pointed implements of bone or ivory shown in Fig. 102, the butt ends of which terminate in a single human figure or in two placed back to back, always conventionalized in the manner typical of the Marquesan artificers in wood and bone, were employed in piercing the lobe of the ear for the reception of ornaments of various kinds. For these and for some other objects in the collection the native name, or rather a description of the object in Marquesan, was obtained by the collector. In this case it is so tersely comprehensive as to be worth quoting here : taa tui puaina ketua; taa, a thorn or point, tui, to beat or pound, puaina, ear, ketua, bored. It could hardly be put more concisely ; one hopes for the sake of the patient that all was as quickly done as said. Yet, if tui was used advisedly with full appreciation of its second meaning, especially, it must be admitted that the hope is not particularly well founded.

The teeth of the cachalot or sperm whale provided the material also for some of the ear ornaments (Fig. 103) worn by the wives and daughters of chiefs. The shaft which projects from the sides of these was passed through the opening in the lobe of the ear and secured in place by means of a button of bone or shell or wood fitted on to the end.

Museum Object Number: P2159

Image Number: 115

It is said that the grotesque figures in recognizably human form which are a constant feature of the carvings in wood or bone or whale ivory, as well as the independent figures, large or small, of wood or stone, are representations of the minor gods, who are in fact deified ancestors. While this is no doubt true in general, it seems likely that the groups of minute figures which appear in the ear ornaments are an exception. That the conventions which are universally observed in the large carvings—the disproportionately large head with round staring eyes and flattened nose with flaring nostrils, the short body with arms bent at the elbow and hands resting on the abdomen, or, in some cases, with one hand raised to the lips—that these conventions are for the most part neglected in the case of the ear ornaments is not in itself decisive, for the restrictions imposed by the smallness of the space available may have led to this departure from established rule. This limitation and the fact that in most instances the figures are arranged in groups engaged in some kind of vigorous action may have led to their being represented usually in profile, and, though the carving is a jour, to the use of a technique which is rather that of a draughtsman than of a sculptor.

What kind of activities are here represented? Definite information is lacking on this point as it is concerning most of the facts or ideas that the Marquesan carvings symbolize or represent. Our knowledge of the aboriginal customs also leaves much to be desired in the matter of coherence of details and of definiteness. Yet an examination of these minute carvings seems to show that some of them are intended, if not to illustrate directly, at any rate to symbolize, certain of these customs.

The two small figures at the top of Fig. 103, the treatment of which is, by the way, markedly more plastic than that of the others of this group, are shown supporting two cubical objects on a flat surface. A comparison of this with the two pairs of ornaments at the bottom of the illustration reveals these objects as human heads. In connection with what seems to be the formal presentation or offering or depositing of heads here depicted it is interesting and suggestive to read the following account of customs associated with the human sacrifices and the service of the temple or moral. ” The Mo’a,” we are told, “were the bearers of idols. They guarded the victims . . . , strangled them, prepared the heads, were, in general, the assistants, sometimes the messengers of the priests” [Dr. Tautain, L’anthro-pophagie et les sacrifices humains aux Iles Marquises, L’Anthro-pologie, VII (1896), p. 448]. ” The head [of a victim], after having undergone a process intended to preserve it and especially to keep the hair on it, was placed on an alter and kept there for a very long time” [loc. cit., p. 446].

Museum Object Number: P2159

Image Number: 116

The ear ornaments in the second and third row from the top of Fig. 103 and the left hand member of the next pair but one below have an important feature in common. The figures are highly conventionalized and fragmentary and it is practically impossible to unravel all the tangled detail of posture and action; but it is clear in several cases that there is a figure at the bottom of the group clutching and being clutched by the fingers or toes of the other figures, who are also clutching, apparently struggling with, one another, and at the same time holding down the prone figure. Several of the upright figures have at first sight a curiously birdlike appearance, being apparently provided each with a long bill. But closer examination shows that this member terminates in a hand; it is not a bill nor a proboscis, but an arm, a severed limb held in the mouth, in all probability. That there is no line drawn across it to mark the place where the severed end enters the mouth is not especially significant in view of the small size of the carvings and the length to which stylization of the figures has been carried.

Let us see what light is thrown on this grouping of the figures, so far as we have been able to determine it, by the pertinent portion of an account of the procedure at cannibalistic feasts. “Everybody,” we read, “threw himself upon the corpse to make sure of a portion. If a man had no [bamboo] knife, he would tear the skin loose with his teeth in thick gobbets from around the nipple and could then, I was assured, rip the whole arm off with a single tug” [K. von den Steinen, Reise nach den Marquesas Inseln, reprinted from Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde, Berlin, 18981. It is noteworthy that one of the figures on the fan handle shown at the left in Fig. 101 is carrying a severed arm over his shoulder.

Whatever may have been the original connection between cannibalism and human sacrifices in Polynesia generally, there is no doubt about their close association in the Marquesas. Victims for offering to the gods were obtained from neighboring settlements at the instance of the superior priests. On the death of one of these priests, three victims had to be secured. Two of these were hung up in the morai—the wasting of the flesh on the bodies was equivalent to its consumption by the god to whom the offering was made; the third was cut up and eaten by those privileged to be at the ceremony, the Tauas, or superior priests, persons of distinction in the community, their relatives, the captors of the victims, and such other persons as the Tauas might summon. Apart, however, from such occasions as these, cannibalism was practised by the people of Nukahiva, in the case of enemies slain or taken in battle; and, in times of scarcity of food, men would slay and eat even members of their own families. The feasts of the profane seem to have been held, not in the moral of the Tauas, but in large paved or leveled open spaces which were devoted to public festivities of various kinds.

Museum Object Number: P3282

Image Number: 112

The large wooden figure, Fig. 104, was taken from a spot near the valley of the Taipi, the ” Typee ” of Herman Melville’s classical account so named of Nukahiva in the forties of the last century. These figures of lesser divinities were set up in the morals. Sculpturally, they exhibit the same general characteristics as the smaller figures in wood or bone or stone; but it is interesting to note that as the dimensions of a figure decrease the importance of the head is preserved at the expense of other portions of the body, the legs especially tending to dwindle, until in some of the smaller figures of bone they practically disappear, while the head retains its impressiveness through the grotesquely disproportionate largeness of its size. On each cheek this figure bears a curious mark carved in relief, presumably a representation of similar marks tattooed on the faces of the men. These two marks are quite similar in their general outlines, the main tracery forming a somewhat irregular cross. The details of the filling between adjacent pairs of arms are slightly different in the two cases. This cruciform symbol appears again and again in slightly varying forms on the objects we have been considering, all of which, as we have seen, have a more or less direct connection with the ritual sacrifice of human beings. It occurs on the back of the head of the figure carved on the bone cylinder attached to the war trumpet (Fig. 87) ; in the same position on one of the figures on the cylinders which decorate the sling for carrying a calabash (Fig. 91); between the hands on the abdomen of that figure; on two, at least, of the ear ornaments (Fig. 103) ; and twice, in a design which may, perhaps, be its prototype, on the narrower sides of one of the fan handles, between the two human figures which form the principal feature of the ornament (Fig. 98). In this last case it appears to be constituted by the combination of four elements each of which suggests the regular conventional method of representing a hand [Cf. Figs. 84,94,97,104, etc.]. It occurs also sometimes on the clubs.

Museum Object Numbers, From Top Left: 18008D / 18008F / 18008B / 18008A / 18008J / 18008E / 18008G / 18008C / 18008H

Image Number: 100

Museum Object Numbers, From Left: 18008B / 18008G / 18008A / 18008E

Image Number: 101

That the use of this symbol in all these classes of articles, and others besides, indicates a connection, probably magical, with the rites to which their employment is in one way or another related seems certain. The precise nature of that connection remains doubtful. The cruciform mark, whatever its exact significance in the instances of its use illustrated here, a significance probably not less bloody than that of the hook, exercised its magical influence on certain occasions on the side of mercy. ” When, living or dead, an individual had been captured as victim, if his family could find out to what district he had been taken, it was possible for his wife, daughter, or mother, perhaps other relatives, to pay him a last visit. For that purpose they bared their bodies completely and daubed their faces with charcoal, whence the name kopeka kaahu ahi which was given to them. This costume assured them freedom to approach the victim and to return home safe and sound, without having undergone any insult or ill treatment” [Tautain, loc. cit., p. 451]. The interpretation given of the native words in this passage ” [adorned with] many crosses of charcoal or soot,” is probably not quite correct, the grouping of the syllables is apparently faulty: kaahu ahi stands presumably for ka (?ta) auahi. If this is so, the meaning would be simply ” cross of smoke (scil. soot).” Dr. Tautain adds, ” and in fact the daubing in question took the form of a cross” [loc. cit., footnote].

Museum Object Number: 18008I

Image Number: 102

The fan handles (Figs. 93-101) are fully carved on all sides. The full face view of the principal figures represented is seen on the narrow sides. The wider sides are filled in with subsidiary ornament, chiefly, human faces, parts of the body, designs resembling those composing the bands of formal ornament on the clubs. In one case a two headed seated figure appears (Fig. 96). Some of these figures have one hand raised to the lips (Figs. 95, 99, 100).

Museum Object Number: 29-93-43

Image Number: 60

Museum Object Number: 29-93-43

Image Number: 61

Museum Object Number: 29-93-43

Image Number: 59

This latter feature appears also on a figure represented as in a seated posture (Fig. 106), which has probably been cut off from the shaft of a canoe ornament similar to Fig. 105. Objects like the latter have been described as supports for the yards of canoes. But the triangular matting sail of a Marquesan canoe required no yard that would cross the mast at right angles and thus rest naturally in such a crotch as is provided by this object. On the other hand, Captain Cook in describing the canoes of these islanders speaks of the head, i.e. stem, projecting “horizontally, and . . . carved into some faint and very rude resemblance of a human face” [Voyage II, i, p. 311. Land. 1777, W. Strahan and T. Cadell]. This corresponds with the carving of the portion of this object which would project over the water if it were attached to the stem or stern of a canoe. The holes in the wood provided for attaching it are at the wider end where the figure is seated. Lisiansky, writing in 1804, speaks of ” a crooked piece of wood” fastened to the stern, “through which runs the sheet of a triangular sail, made of matting” [A Voyage round the World . . . in the Ship Neva, London, 1814, p. 90]. According to the account given of the Marquesan canoes by Roblet, the surgeon who accompanied Captain Marchand in the Solide, “their stern is terminated by a projecting piece, which imitates very imperfectly the flattened head of a fish, or rather the under jaw of a pike” [A Voyage round the World performed by Etienne Marchand (1790-1792), Vol. I, p. 118. Land. 1801]. At any rate the projecting figure set at an acute angle to the shaft appears better suited for hitching a rope over than for the support of a yard. This object is most likely an ornament like that described by Roblet, taken from a canoe model.

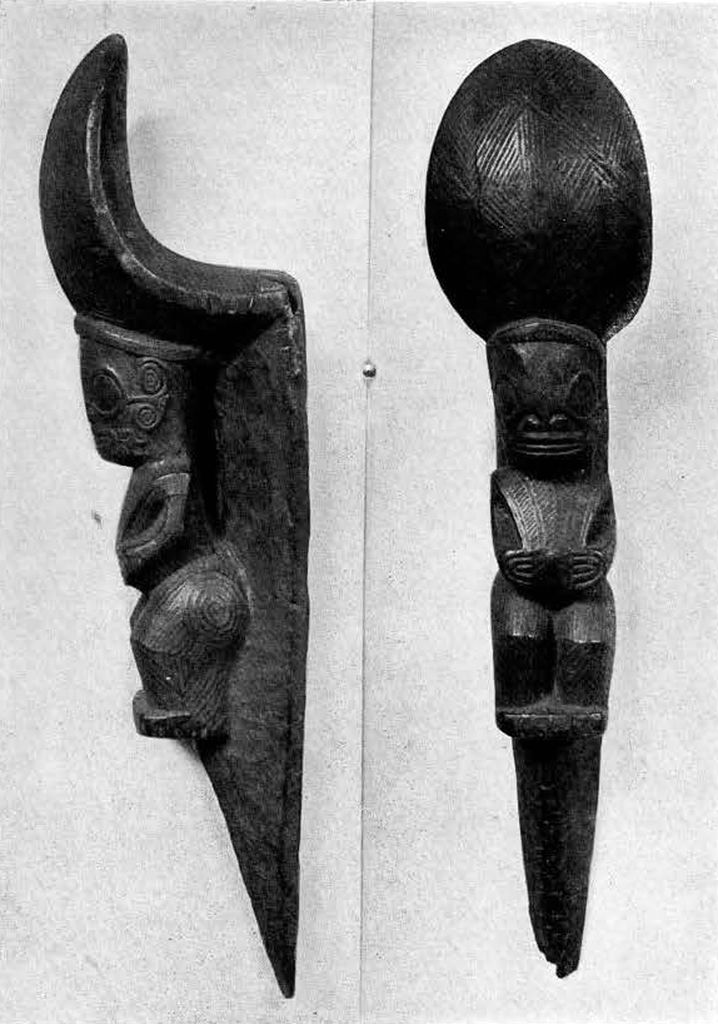

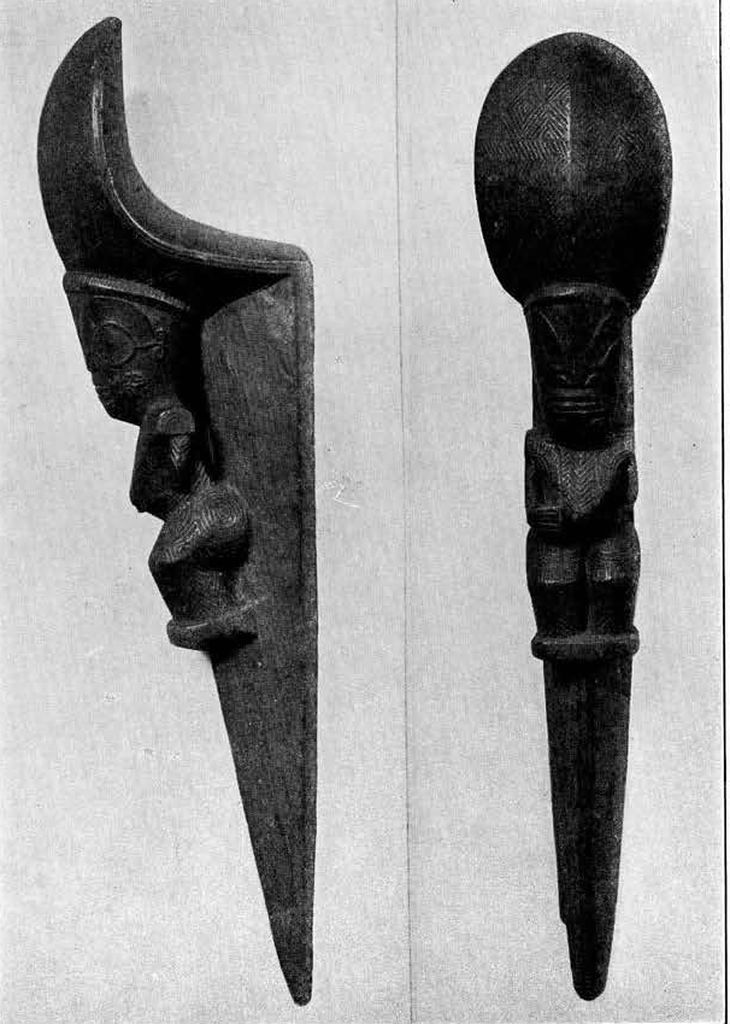

The peak which crowns the head of this figure gives it an outline differing both from the others hitherto described or illustrated and from those which form the foot rests which were attached to the stilts used by the Marquesans (Figs. 107-112).

Although he misunderstood the purposes for which the stilts were employed, the editor of the notes made by Marchand and his companions Roblet and Captain Chanal has given an excellent description of a footrest taken to France by Chanal. It applies in most particulars to the examples illustrated here. “Each stilt is composed of two pieces: the one, of hard wood and of a single piece, may be called the step; the other is a pole of light wood, more or less long, according to the stature of the person who is to make use of it. The step is eleven or twelve inches in length, an inch and a half in thickness; and its breadth, which is four inches at the top, is reduced to half an inch at the bottom. The hind part is hollowed out like a gutter or scupper, in order to be applied against the pole, as a check or fish is, in sea-terms, applied against a mast; and it is fastened to the pole . . . by sennit or lashings of cocoanut bass: the upper lashing passes through an oblong hole, pierced in the thickness of the step; and the lower one embraces, with several turns, the thin part, and confines it against the pole. The projecting part, which I should call the clog, and on which the foot is to rest crosswise, bends upwards as it branches from the pole; this clog is an inch and a half in thickness; and its shape is nearly that of the prow of a ship, or of a rostrum, or, if the reader please, that of a truncated nautilus. The under part of this sort of shell is slightly striated throughout its whole surface, and the striae commence from the two sides in order to join in the lower part on the middle, and there form a continued web; its upper surface is almost flat for receiving the foot, and it is in like manner ornamented with striae of no great depth, which form regular series of salient angles and of reentering angles. The clog is supported by a bust of a human figure in the attitude of a Cariatides (sic), wrought in a grotesque manner, which greatly resembles a support of the Egyptian kind; it has below it a second figure of the same kind, but smaller, the head of which is placed below the breasts of the large one; the hands of the latter are placed flat on the stomach, and its body is terminated by a long sheath, in order to form the lower and pointed part of the step. The arms, as well as the other parts of the body of the two figures, are angularly striated, like the upper face of the clog” [Marchand, I, 119-120]. This answers generally to the appearance of the University Museum’s specimens. None of the latter examples, however, has a double figure. The author of this description supposed that stilts were used by the Marquesans as a means of getting about during inundations in the rainy season. Langsdorff [Voyages and Travels in Various Parts of the World during the Years 1803-1807, p. 151. Carlisle, Pa. 1817] justly observes that, “if it should be alleged that the frequency of inundations, and the necessity of keeping up an intercourse with each other, has led them to [the pursuit of stilt walking], I answer, that people who always go naked, and are swimming about all day long, have no great reason to be afraid of wetting their feet, and cannot therefore make use of such a means of keeping them dry from necessity.” He might have added that the nature of the surface of the islands precludes any possibility of extensive flooding of large areas. Langsdorff [loc. cit.] gives a concise account of the use to which these stilts were put. “Next to dancing, one of the favourite amusements among these people is running on stilts, and perhaps no nation on earth can do this with so much dexterity as the inhabitants of Washington’s Islands. At their great public festivals they run in this way for wagers, in which each tries to cross the other, and throw him down; if this be accomplished, the person thrown becomes the laughing stock of the whole company. We were the more astonished at the dexterity shown by them as they ran on the dancing place, which, being paved with smooth stones, must greatly increase the difficulty. Children are thoroughly habituated to this exercise, even by the time they are eight or ten years old.” Further: “It seems that the people of Nukahiwa . . . represent in their pantomimic dances most of the common actions of life, as fishing, slinging stones, running on stilts, swimming and the like” [op. cit., p. 143]. The two footrests shown together in Fig. 112 are from a child’s stilts. The dancing places referred to are the levelled or paved areas in which public festivities were celebrated, to which allusion has already been made.

H. U. H.

Image Number: 64

Image Number: 65

Image Number: 107

Image Number: 66, 67

Image Number: 68

Museum Object Number: 18009A

Image Number: 94, 95, 96

Image Number: 103

Museum Object Number: 18033

Image Number: 69

Museum Object Number: P4805

Image Number: 108, 109

Museum Object Number: 18016A

Image Number: 73, 74

Museum Object Number: 18016B

Image Number: 75, 76

Museum Object Number: 18016C

Image Number: 77, 78