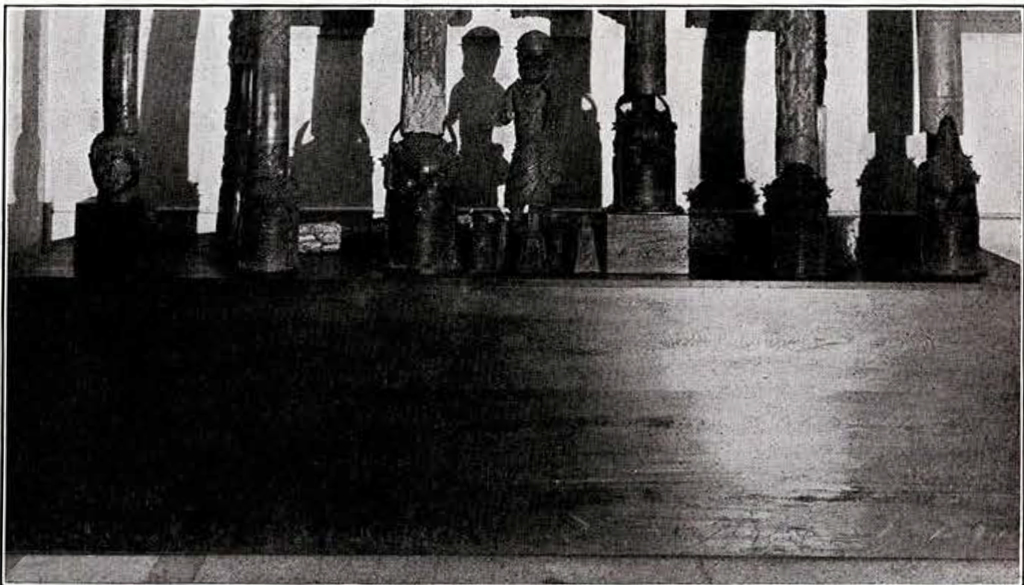

The juju or fetish altar which has lately been installed in the African room is designed to exhibit in something like the setting in which they were probably once grouped some of the most interesting examples of the art of Benin included in the University Museum’s important collections from that formerly powerful negro kingdom.

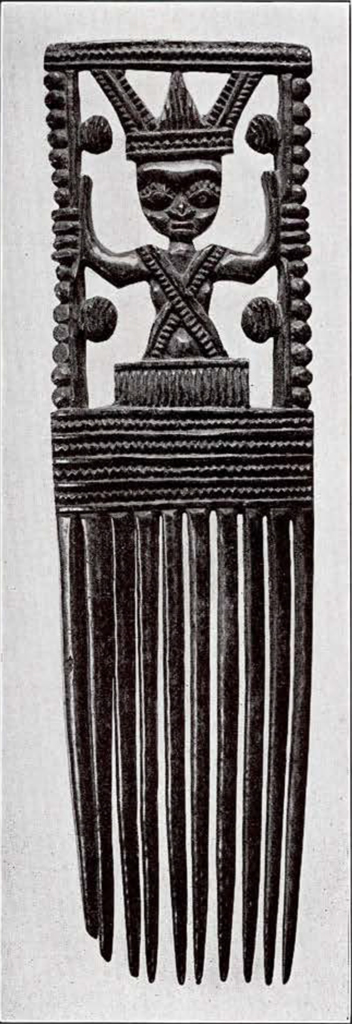

Image Number: 22451

Neither of the words commonly used to denote objects and ceremonies connected with the religious beliefs and magical practices of West African negroes can be referred with certainty to a negro language. Juju and fetish are corruptions, the first probably of the French word for toy, the second certainly of a Portuguese word meaning charm or amulet. Setting aside whatever intention of blame or derision may have inhered in their original use or survived to the present day, the general understanding of their meaning as including a supernatural or magical power of bringing good to the owner or worshipper or celebrant and of working harm to those to whom he or the power represented was not well disposed, is adequate for general purposes.

The king of Benin had his residence in Benin City, or Edo, the capital of the country of the same name which is now a part of the British Protectorate of Nigeria. He passed his life in almost complete seclusion from the lower ranks, at any rate, of his subjects, by whom he was only rarely seen. He exercised his authority through powerful officials and left the compound in which his palace was situated only on certain ceremonial occasions. Through his lieutenants he ruled over territory which at one time reached the sea on the Slave Coast, the flat, low stretch of the West African seaboard between the rivers Niger and Volta.

The king’s power was fetish, he was in a manner divine, requiring neither food nor drink nor sleep to sustain his being; he would die, indeed, but after death would come again to life and his kingdom. He was the object of a service which was of the nature of worship, and the sanctions of which were grounded in fear—the fear of a being whose seclusion surrounded him with mystery, and the arm of whose law wielded a terrible sword. Offenders against that law together with slaves and prisoners of war furnished most of the victims sacrificed to the gods.

The most striking and the essential part of the ritual of the worship of the Bini consisted in sacrifices to the ancestors, who were conceived as directing for good or evil the affairs of living men. These spirits might be angry, and the wider powers which death had conferred on them by association with the spiritual and the invisible, that is, with other spiritual forces and elements never incarnated and always malignant, made their anger most formidable. They must be propitiated, and blood, the essence of life, was an acceptable offering, if not a necessary revivifies, to them. Altars and images, containers of the ancestor spirit, the god, were drenched therefore with the blood of victims, fowls and goats and oxen and men and women. The gods were spirits; other spirits, liberated by bodily death, must be made messengers to them of prayers and wishes, and a human spirit was naturally the most efficient messenger. The gods were subject to the same needs as their children on earth; so, when a king or a great chief died, attendants must be dispatched with him to the spirit world, and others must follow on at each anniversary celebration of his death. For lesser men a lesser sacrifice of fowls or goats or oxen must serve; though the poultry yard and the herd were not spared in the former case either.

Museum Object Number: AF2032

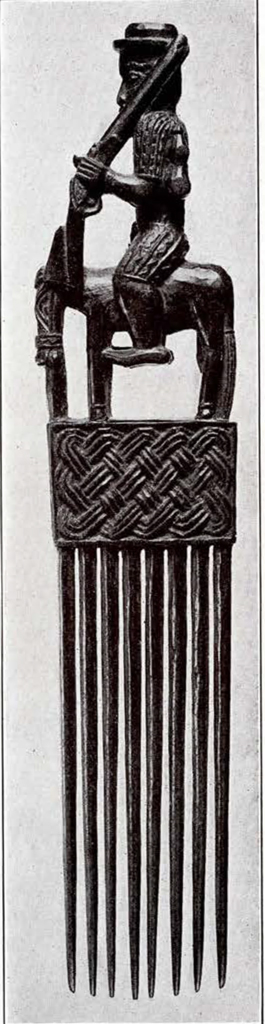

Image Number: 629

As being himself fetish and representing the interests of his divine predecessors, the king had the right to sacrifice human victims.

This prerogative was not unique. The chief officials, agents of his powers and kingly functions, though but one of them bore a priestly title, shared also this sacerdotal prerogative, and were thus strongly entrenched in all fields, military, civil, and religious, over which the royal power extended, and, wielding that power for the king, kept him in the background, an awe inspiring puppet invested with all the influences of superstitious terror which were the sanctions of the acts they performed in his name.

Not only the king, then, but also the queen mother, the captain of war, the principal judge, and the chief priest might sacrifice human beings to their ancestors. From these ancestors they inherited their offices, and, like the king, thus wielded power by a kind of divine right ; since ancestors who are sacrificed to, and to that extent worshipped, are, if not already deified, at least in a fair way of being so. Benin was, it seeps, a holy city—it was cut off not only physically by a wall but spiritually by a kind of taboo from the rest of the kingdom—governed by a hierarchy whose members were possessed of varying degrees of supernatural power. Apparently the city maintained its supremacy over the other towns of the kingdom chiefly by the superstitious awe which this theory of government inspired, supported as it was by the bloody terror of ritual murder.

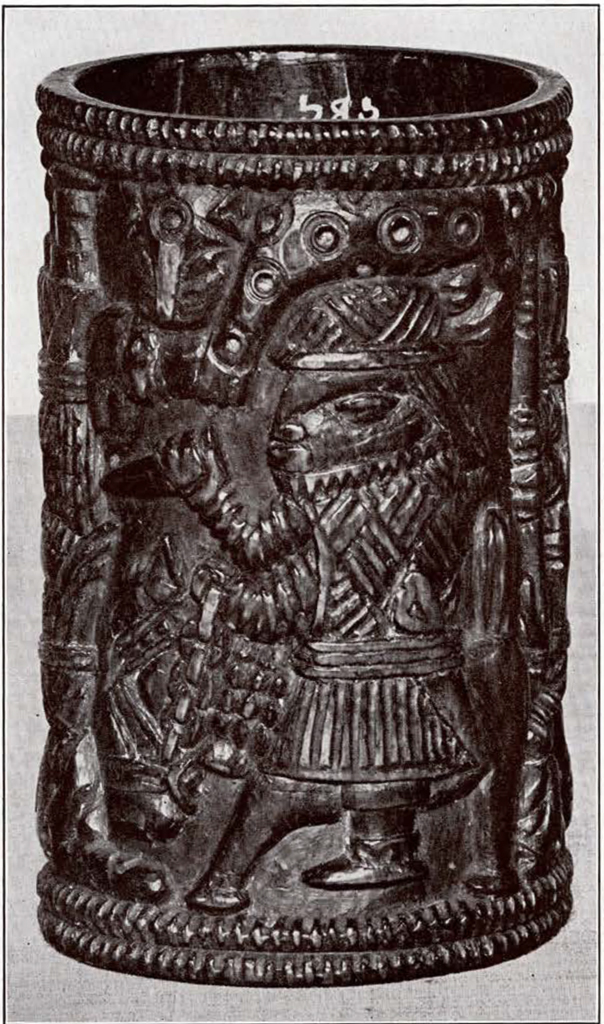

Museum Object Number: AF5107

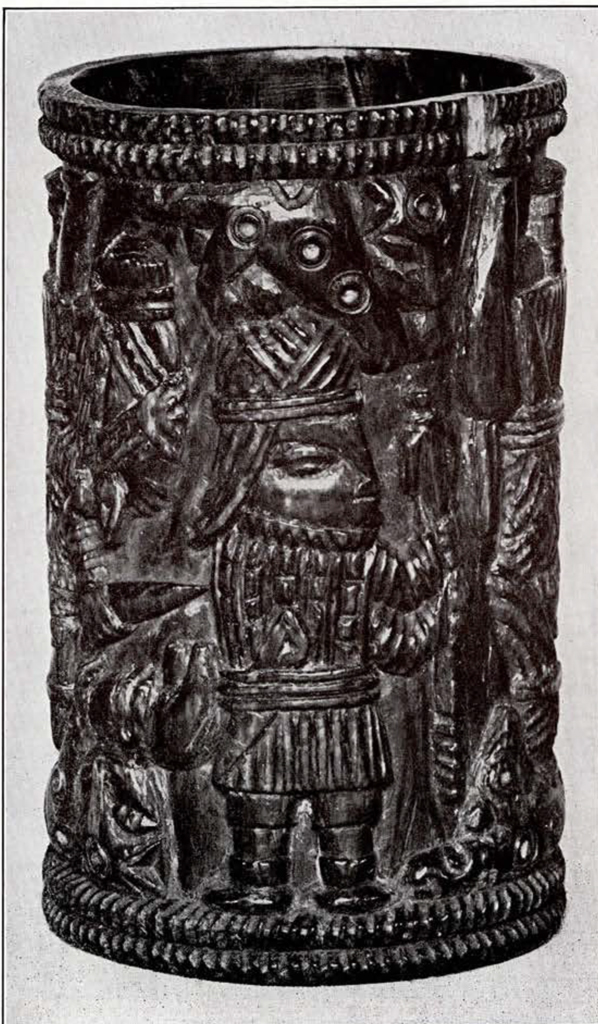

Image Number: 22454

The actual slaying of victims was deputed to a professional executioner, a public official of considerable importance. If the act of killing was originally essential to the office of celebrant at these sacrifices, perhaps we may see a survival of the primitive exercise of this right or duty in the circumstances that attended the capture of a leopard by a hunter. “When a man killed a leopard he had to take it to the Oba (king), who gave the hunter a boy and a girl in exchange for it. The Oba used to try very hard to obtain the leopard alive, so that he might sacrifice it. On doing so he would put his finger into its blood and make a mark with it on his forehead, from his hair to his nose” [R. E. Dennett, At the Back of the Black Man’s Mind, p. 229]. Here we seem to see the king in his double capacity of priest and god, offering in his own person a sacrifice to himself ; for an essential part of the ritual of sacrifice on other occasions was the sprinkling of the fetish images of ancestral deities with the blood of the victim.

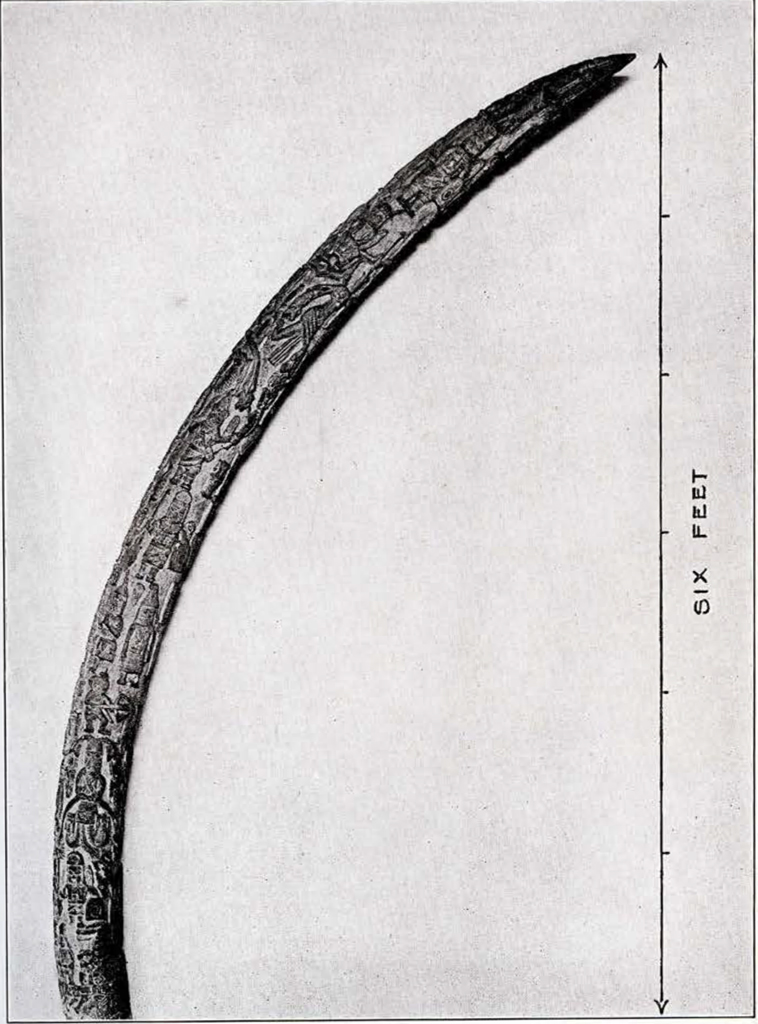

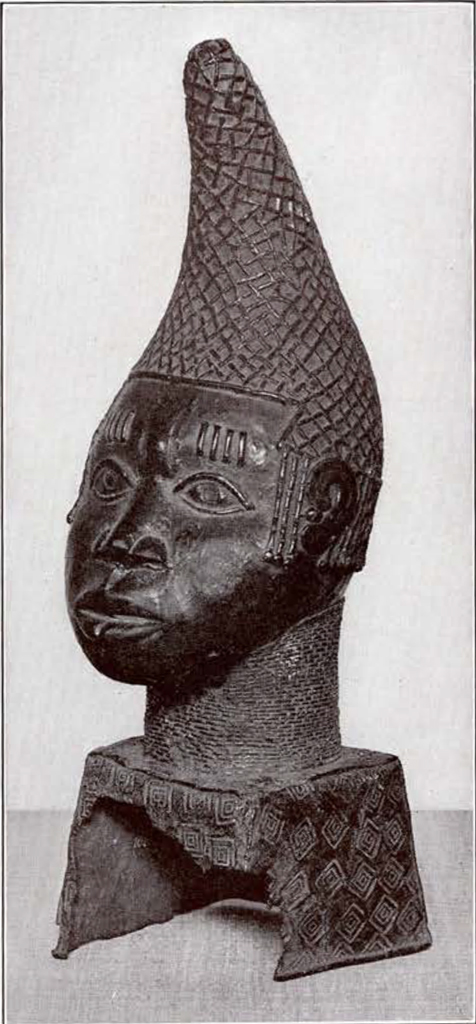

There was a considerable variety of such images, for the cult of ancestors was not confined to those of the king; every family owed worship and sacrifice to the spirits of its forebears, and these were supposed to inhabit objects of several kinds and forms. The king’s special fetish was a representation in bronze or brass of a human head, probably a portrait of an ancestor, surmounted by the tusk of an elephant often carved all over with figures of men and animals. These were set up on altars which there is reason to suppose were in some cases also the tombs of royal ancestors.

Image Number: 645

A photograph of such an altar, taken several years before the British occupation of the city put an end to the orgies of slaughter which marked the native rule, is reproduced in Great Benin, H. Ling Roth’s history of the kingdom [Halifax, 1903. P. 79]. The smaller details are not distinguishable in the picture, and cannot be supplied from the scant description which accompanies it. The altar (Figs. 32 and 33) does not claim to be an exact reproduction of that shown in that early photograph, but the general arrangement is similar, and the only object upon it which may not be in place there is the bronze figure in the center which takes the place of the small figures referred to in the legend accompanying Ling Roth’s photograph. All the other objects are appropriate to a king’s altar, of which there was more than one in the precincts of the palace.

The town was burnt, accidentally, on the third day of occupation by a British force sent to punish the massacre of the members of a peaceful mission to the king a little more than a quarter of a century ago. Descriptions of the city and of the king’s compound written before that time and others produced since then, based on native information, are either not very full or not in all respects consistent with each other. It appears, however, that in one or more of several large courts included in the king’s compound or enclosure an altar or altars of dried mud resembling Fig. 33 rose from a bench of the same material which ran along the mud wall, and that before these altars sacrifices were offered of all kinds of victims including human beings.

Museum Object Numbers: AF5107 / 5081

Image Number: 22455

It was a widespread custom throughout the Slave Coast and its back country, not simply to place the heads of human victims temporarily on altars or in shrines but to preserve the skulls there permanently [A. G. Leonard, The Lower Niger and its Tribes, pp. 292, 177-179; and cf. Sir R. F. Burton, Wanderings in West Africa, frontspiece and pp. 282-283. London, 1863]. It is, no doubt, due to a modification of this custom that bronze heads standing on no other base but that of their own necks came to be used as altar furniture by the Bini kings. Some words quoted by Burton in the passage just referred to seem almost startlingly apposite in this connection. He says: “As there had been no prisoners of late, I saw none of those trunkless heads which, placed on their necks, with their faces towards the juju-house, present a dreadful and appalling appearance, as of men rising from the ground.” What Burton himself saw was the juju altar with a kind of reredos decorated with rows of skulls of men and goats, the relics of former sacrifices. Though he is speaking of Bonny, not of Benin, it is known that, in addition to the general relationship implied by similarities of beliefs and ritual practices among all the peoples of the region, there was an actual bond of a politico religious nature between these two states in the early part of the last century. That the custom in Benin of keeping artificial representations of human heads on the altars had not altogether superseded that of keeping skulls there is shown by a photograph in the book Great Benin of an altar in a private house “near the king’s, in which a noble lived. It was part of his office to kill a slave every year for the king and put the skull on the altar” [p. 64].

The bronze heads on the king’s altar formed each with its superimposed tusk the special fetish of the king representing an ancestor. The available information does not enable us to trace the process by which the skull of a sacrificial victim may have developed into a fetish which was also apparently a memento in the nature of a portrait of a royal ancestor. In West Africa, however, new cults are always arising or new features of cults becoming grafted upon old ones. If the skull was the representative of a spirit messenger sent to communicate with the spirits in the world inhabited by the royal dead, it might by contact absorb some of their royalty or divinity. The transition would be assisted by circumstances which, according to the native tradition, completely revolutionized Bini representative art.

Image Number: 22455

In the reign of Esige, the ninth successor of the founder of the dynasty which was overturned by the British occupation, there was attached to the court of Benin, or living in the town, a white man, Ahamangiwa by name, who, being skilled in bronze founding, was commissioned by the king to make portraits of the captives taken in an expedition against a neighbouring tribe. Certain of the king’s boys were assigned to Ahamangiwa to assist him and to learn this new art. We know the fate which commonly awaited prisoners of war. For what other reason can portraits of captives have been wanted than to take the place on the altar, in durable bronze or brass, of their perishable skulls? Having been set up there in association with objects representing royal ancestors, viz., the carved tusks and the rattle staves (Figs. 32, 41 and 42), the suggestion was ready made to immortalize royalty more directly and palpably by a still closer association of its actual presentment in bronze with its more abstract emblem in ivory—the king’s portrait or his father’s with the ancestral symbol, the tusk. The tusks would be at once more suitable and available than the staves for this purpose, as they were a perquisite of the king and were immobilized on the altar, while the staves were removed from it for use during the ceremonies which accompanied sacrifices.

Native tradition is, of course, notoriously a guide on which reliance for the course or the details of historical events must be placed with caution. But the circumstantial relation by a court historian of Benin of facts which link up well with known events in the history of the close Portuguese relations with Benin is evidence at least of probability. When, for instance, we know from a letter written to Dom Miguel of Portugal in 1516 by one of his subjects then residing in Benin as a friend of the king that Portuguese missionaries accompanied a Bini force on a military expedition and remained with it a year, the likelihood of a Portuguese Ahamangiwa’s connection with the court of Benin, as official maker of bronze portraits of war captives and teacher of that art, is certainly enhanced If any event is likely to make an unchanging impression on the memory of a people—a people provided, too, with an official historian—it would be the circumstances of the introduction of a new art, which, although sufficient time had elapsed since its introduction to allow of its almost complete decay, they still recognized as originally a foreign importation.

Museum Object Number: AF5082

Image Number: 142936-1

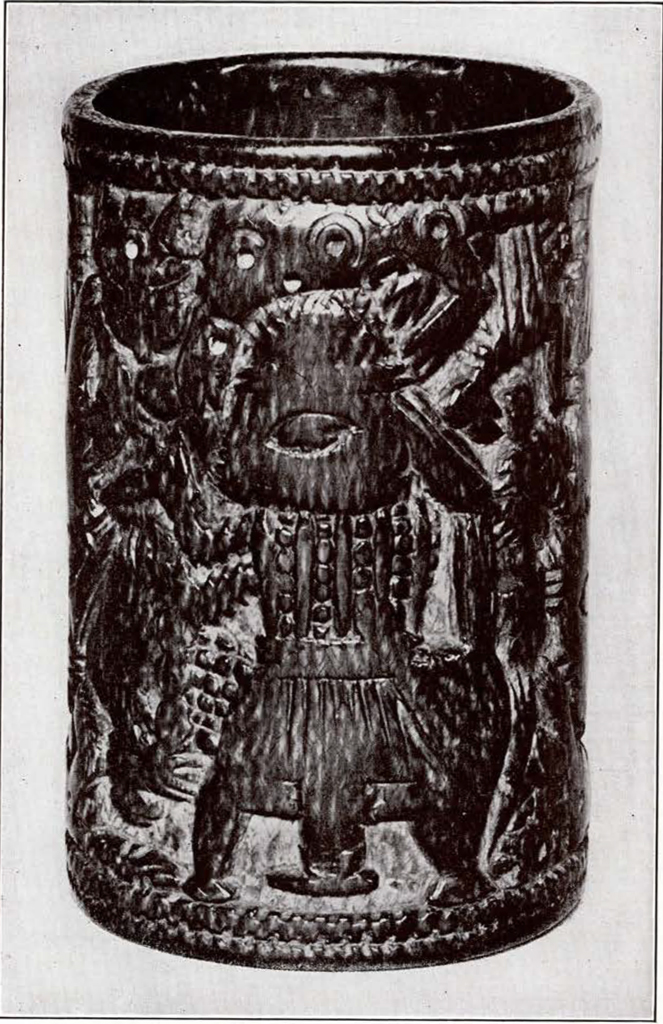

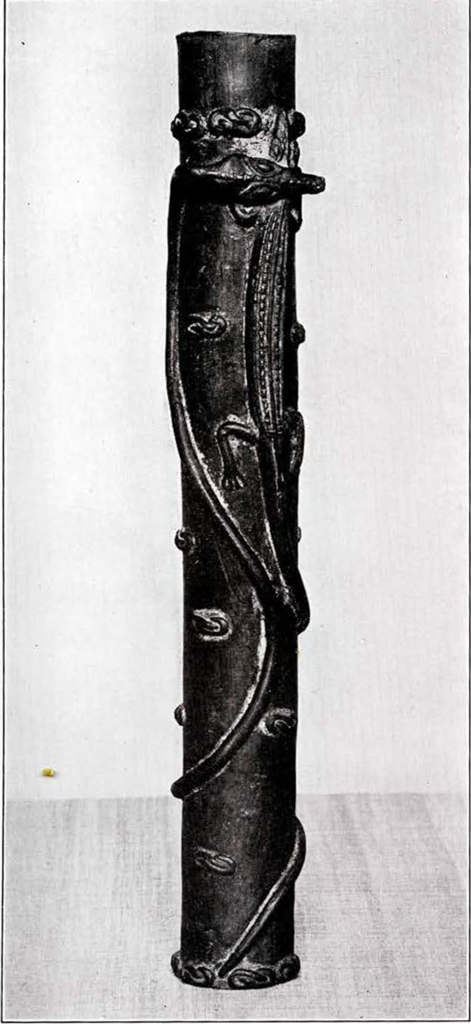

Before passing to the consideration of the bronzes in question, and beginning at the back of the altar proper, the first objects to be noted are the uchure or rattle staves (Figs. 32, 41 and 42). The carvings on these are disposed according to sections corresponding, we are told, to the internodes of a stick of bamboo.

The longer staff has three figures including the principal one at the top, presumably the ancestor proper. There is nothing to show that this is a royal uchure ; the topmost figure wears a breast ornament of the same character—perhaps one of the brass powder flasks such as were made by the Bini metal founders—as that of the seated attendant near the butt of the staff, who is apparently beating a drum. The female figure in the center holds in front of her a frame, perhaps a dish, within which are two round objects similar to the one carried in the left hand of the principal figure above, who holds in his right an uchure.

Museum Object Number: AF5102

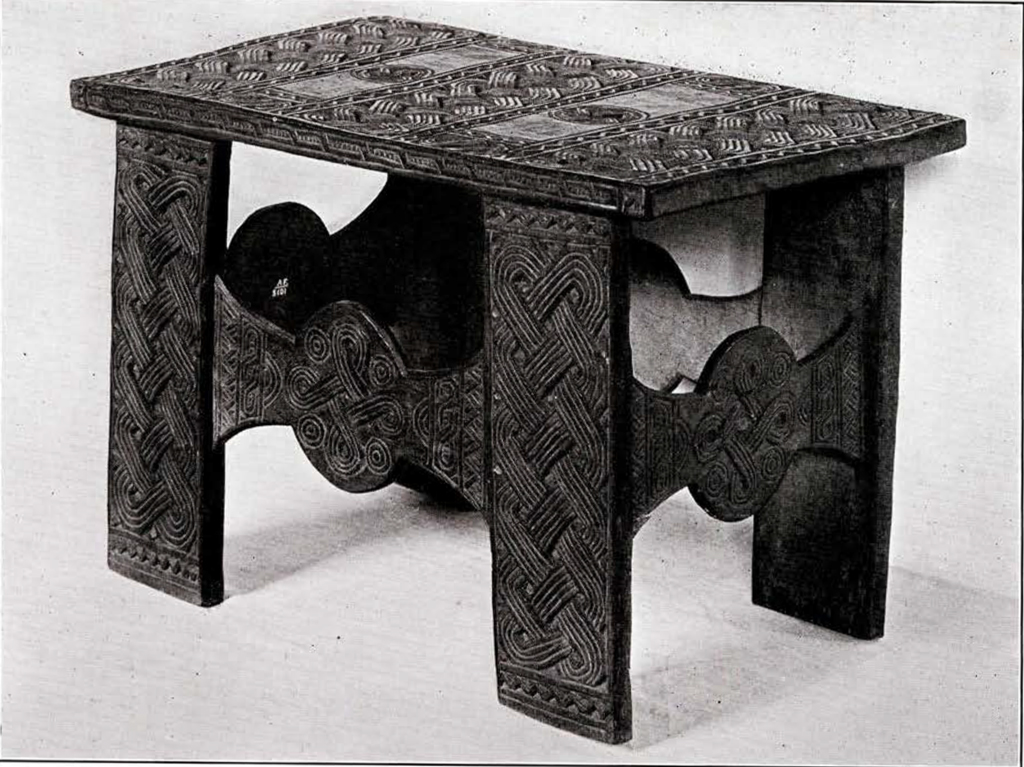

Image Number: 2422

The other uchure, though shorter, is more elaborately carved, even the sections which are not occupied by figures being covered with designs probably intended to imitate matting, including the favourite bands of guilloche which occur so frequently in Bini decoration, notably at the bases of the fully carved tusks and as the only ornament on the others. There is only one attendant figure here, but he is a person of importance since he carries an executioner’s sword and a wand which is perhaps the king’s taboo sign. His anklets are a mark of rank befitting that important personage, the executioner. The forehead and body have the regular Bini cicatrized markings.

The figure with which this staff is surmounted has the spiked headdress which appears again on some of the principal figures of the carved tusks. He wears no anklets, but he has that other mark of high rank, the cylindrical collar of beadwork. The forehead and body are marked with cicatrizations. The front of the body is crossed by two baldrics of beadwork. The left hand grasps an uchure and the right an object which may be intended to represent a stone celt, such as are found on or near the surface of the ground in that part of Africa and are regarded by the natives as having a supernatural origin and power. The figure stands on an elephant whose trunk ends in a human hand holding a feather. The representation of an elephant’s head and trunk, the latter furnished with a hand usually grasping some object, is frequent on Benin ceremonial or ornamental objects, especially those of bronze and ivory. Its occurrence on objects known to have been associated with royalty affords ground for assuming that it is symbolic, representing some attribute of the king. The impressive size and strength of the elephant and the uncanny dexterity shown in its use of the powerful proboscis with the prehensile fingerlike extremity—double in the case of the African elephant—which would easily suggest a hand even to the not very nimble fantasy of a Bini artist, makes of the beast a fitting symbol of royal or divine power. As we have seen, elephants killed by hunters formed an appanage of the king. The evidence that this is a royal uchure and that the upper figure represents a king is made conclusive by the close resemblance of the top of the staff to that of the brazen staff of office of Eduboa, the king of Benin who was deposed by the British in 1897. The metal staff, said to have been in Eduboa’s family for many generations, has the form of an uchure of which the topmost section shows a king holding similar objects and standing on the back of an elephant. In the example before us the animal is very cleverly represented according to conventions made necessary by the dimensions of the object of which it was to form a part, by the purpose the animal was to serve in the carved group as a pedestal for the principal figure, and by the artist’s material. The body and limbs are compressed into a squat cylindrical form, the trunk and tusks which in the brazen uchure project naturally, are here carved in relief on the front of the head, the tusks converging at their extremities to form a V, and the rugose trunk, characteristic of the African elephant, being carried across laterally so that the mythic hand clasping a feather shows against the disc of the right ear.

Museum Object Numbers: AF5077 / AF2043

Image Number: 633

The rattle staves, found also on other than royal altars, had not merely the passive function of representing there the ancestors sacrificed to. Their principal use in the ritual of the sacrifices was as rattles to attract the attention of the spirits. The bells placed on the altar were used for the same purpose.

Bells like these were worn as pendants on the breast (Fig. 43) ; and masks like those which are represented in miniature on the bells were worn as ornaments attached to the girdle.

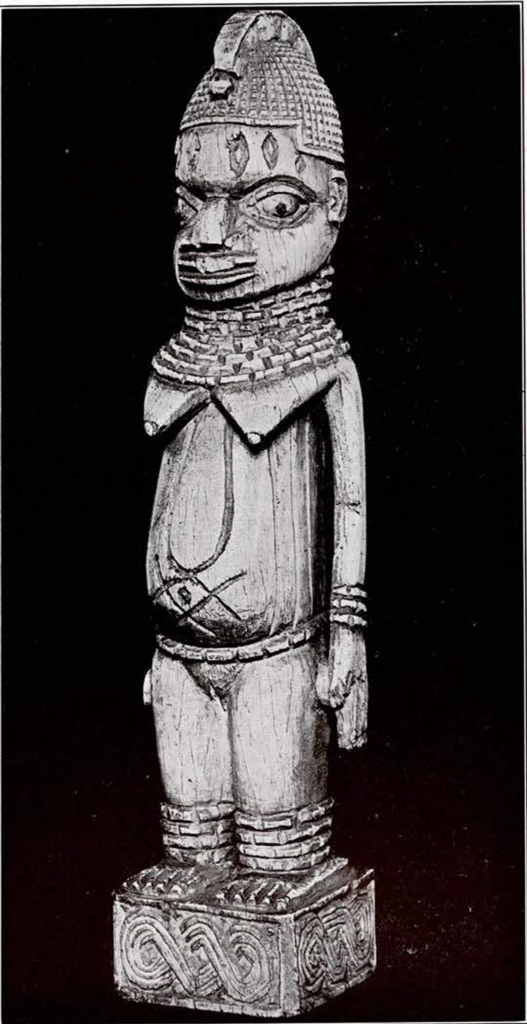

The figures of the wood and ivory carvings and of the bronzes cannot be regarded, except in a very few cases, as representations of characters in historical incidents. They are type figures of notables—kings, officials, and the like—with the attendants proper to their rank or suggestive of attributes or functions peculiar to it. This naive symbolism, which is most fully carried out on the carved tusks, cannot be fully interpreted, but at least in some cases its meaning may be inferred with probability with the help of our rather fragmentary knowledge of Bini customs and beliefs.

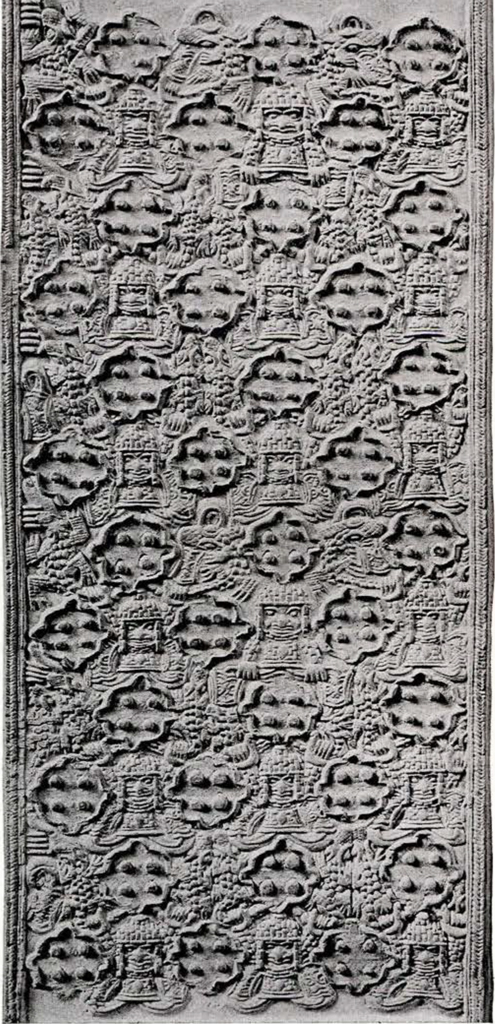

It is from the tusk to the right of the bronze figure on the altar that we may get the clearest idea of the arrangement of the symbolic figures. They are carved in rows or tiers around the tusk. This is clearly the ideal plan at any rate, though in the case of some tusks, notably the large one lying on the altar (Fig. 34), the general scheme is obscured by the crowding in of subsidiary figures, thus confusing the rows. Some of the tusks were damaged by fire in the conflagration referred to in the earlier part of this article. In the case of the tusk now to be described the tip has been somewhat charred; but a comparison with the one to the left of the bronze figure shows that it was carved into the semblance of a head wearing a helmet of beadwork culminating in a tall spike and with streamers made up of what seem to be large beads and strips of cloth or matting depending from the back and sides.

Immediately below this on the outer curve of the tusk is a full length figure wearing a similar headdress. Its body is covered by a long shapeless robe of matting, quite unlike the characteristic Bini costume as worn by most of the other figures. Bearing in mind that this tusk was a king’s fetish, symbolizing his royal and divine ancestry; that it bears as the most prominent features of its carving, as will be seen, other representations of a deceased king in his divine character; that such tusks were set up on the tombs of kings, which were probably in some cases at least also royal altars; that it was before such altars that the king made father, i. e., sacrificed annually to his deceased predecessor; and, finally, that in Southern Nigeria generally, and among the Edo speaking peoples in particular, of whom the Bini are the chief, corpses were wrapped in matting before being buried, it seems hardly doubtful that this is a representation of a royal ancestor in his grave clothes. He carries two curved rods the ends of which converge above his head, evidently the peeled wands which were the king’s taboo sign, by means of which he closed roads, which were carried before and behind the bearers of gifts to or from the king, and which were placed upon the altars.

Museum Object Numbers: AF5077 / AF2043

Image Number: 634

On this tusk the principal figures are carved one above the other along the mid line of the longitudinal outer curve, each forming with attendants and other subsidiary figures a group the members of which are ranged alongside of each other round the circumference of the tusk. All but two of the chief figures, and these are not certainly exceptions, represent the king with certain royal or divine attributes.

Behind the first figure, on the inside curve of the tusk, is shown a leopard with its tail turned towards the tip of the tusk. It is holding a horned animal, probably an antelope, in its jaws. The leopard, as we have seen, was associated with royalty, as was the elephant. In the brazen uchure of Eduboa, already referred to, an elephant is represented near the butt of the shaft with two leopards as supporters.

Apparently all indigenous animals conspicuous for qualities apt to inspire respect or terror came to symbolize the royal power; at least they were in the royal control. The elephant is beneath the feet of the king in the wooden uchure (Fig. 42) and in the brazen staff of Eduboa, the leopards in the latter stand beside the elephant supporter of the royal figure; and here the next figure, representing the king in his character of a powerful fetish, holds in each hand a crocodile by the tail. He wears on his head a spiked helmet shaped like that of the figure immediately above. It is of beadwork, as are also the high collar, a mark of rank, which encases his neck and chin, and the crossed baldrics upon his chest. Across his waist and depending head downward from it at either side he holds a twoheaded serpent, with a half swallowed frog in each mouth. From each side of the bottom of his kilt (beluku), which has a border resembling the weave of the matting robe of the first figure, issues a catfish, the most commonly represented of the sacred animals of the Bini, and, seeing that it actually forms, as here, part of the body of the deified king, apparently the most sacred. The two fishes take the place of the royal legs. Between them is a wedge shaped object, which reference to the other of this pair of tusks shows to be, probably, an incompletely carved crocodile’s head.

This mythic conception of a fish man has been, I think wrongly, attributed to European influence, on the ground that the early explorers were familiar with the idea of the merman and may have communicated that idea to the native artists. But this is no conventional merman with legs represented as fishes’ tails; each leg is here a separate fish. Besides, the Bini are known to have believed that the king had the power of transforming himself into an animal; and, as may be seen from Fig. 49, and from many other examples in Bini art, the idea is common of animals or parts of animals being attached to the human body, especially as if issuing from orifices, as the nostrils, or, as it might be in this case, from the orifice represented by the bottom of the skirt. In any case we have here the king represented with some of his most powerful fetish attributes, and his superhuman character most clearly indicated by his semi-human form.

Museum Object Number: AF2067

Image Number: 622

Museum Object Number: AF5109B

Image Number: 647

In Oyo, the ancient centre of power of the Yoruba, the artistically gifted people who gave to the Bini the founder of their royal line, the German anthropologist Frobenius found some years ago an old carved wooden utensil in the form of a fish, on which is represented a human face surmounted by a headdress like that seen in the comb (Fig. 52), and with two bent arms proceeding from the nostrils. Apparently the Bini notion of a composite superhumanly endowed being, the same notion as appears in the often recurring elephant’s head with trunk ending in a human hand, is shared with the Yoruba, to whom the Bini owed much besides a dynasty.

Coral and agate beads, and, no doubt, imitations of them in glass, especially in a cylindrical form, were very highly valued in Benin. The finest were the property of the king. Headgear, bodices, baldrics, anklets, necklaces, the cumbrous chokers or collars encircling the neck and sometimes concealing the lower part of the face [cf. Figs. 37, 38 and 43] were made wholly or in part of beads strung on cord or wire. The collars and the anklets especially were badges of rank. Strings of beads, which perhaps formed part of the collars, were conferred by the king on those whom he wished especially to honour. Loss of these gifts, or rather, loans, for they reverted to the king on the death of the recipient, was punishable with death.

In the next row the central figure wears a headdress without a spike but with streamers of beadwork like those that hang from the sides of the spiked headdress and with bead rosettes like those on the headgear of the large bronze heads (Figs. 32 and 38). His choker is extended downwards to form a sort of gorget that covers the upper part of his chest. This gorgetlike ornament appears also on the ivory figure, Fig. .51, which represents the wife of some important personage, perhaps of the king. The tusk figure is dressed in a smock reaching to his knees and decorated with a reticulate design probably representing beadwork. On his chest below the edge of the gorget are two bells. He wears anklets. In his right hand he carries a ceremonial knife or sword with a ring handle and a blade like a fish slice. This is known as an ebere. It was a mark of authority proper to all the chiefs of state, not only to the king. In his left hand he holds a great spear, point downwards. From his armpits hang two long wedge shaped objects, which a comparison with the corresponding figure on the other tusk of this central pair shows to be a sort of scarves forming a part of the costume. Between the butt of the spear and his head an object shaped like two wedges placed broad end to broad end is carved on the tusk. This may be an unfinished crocodile’s head. One of the two figures of attendants in this group supports that hand of the principal figure which holds a spear.

Museum Object Number: AF5108

Image Number: 648

Museum Object Number: 29-94-3

Image Number: 668

It is not quite easy to determine who are represented in this group. Not only the king, but also the queen mother and the captain of war were entitled to have their arms upheld by attendants, a privilege of rank which is not uncommon in West Africa. The personage with whom we are here concerned is a man, which leaves us a choice between the king and his captain of war. Leopard’s skin coats were worn by the latter functionary and apparently also by his attendants; and necklaces of leopards’ teeth seem to have been insignia of warriors. It might be supposed that the attendants

themselves represent the captain of war, duplicated in order to fill in a space, escorting and supporting the king. But in that case these minor figures would be, as they are not, furnished with chokers and anklets, insignia of the great officials, of whom the captain of war was greatest. It seems likely that this group represents the captain of war, with attendants wearing his livery of leopard’s skin coats and leopard’s teeth necklaces, guarding, as it were, the royal figure next below him and symbolizing, as its instrument, royalty’s supreme position and power.

Just below the fetish king appears again. His headdress here has the form of that part of the conventional representation of a catfish which corresponds to the mouth and feelers. His right hand grasps an ebere, his left an uchure. Where the two headed snake crosses his body it is carved into the semblance of a chain with hexagonal links, probably an imitation of the markings of a python. The wedge shaped, faceted object between his catfish legs may be the representation of a thunderbolt celt. In the other of this pair of tusks a crocodile’s head is placed in the same position.

Museum Object Number: AF5104

Image Number: 644

The figure immediately below in the next group wears a jacket of beadwork with two horizontal bands across the front, one at the level of his armpits, the other across the middle of his body. A bell hangs below the upper band and a row of bells at his waist. He wears the choker, and has also a necklace of leopards’ teeth, as well as anklets and bracelets. His beluku has a wide scarf hanging from the left side where the ends are caught up in regulation style, with a huge extension of the stiffened ends of the heavy cloth rising on that side to the level of his head. A beluku consists of several layers of cloth, of which the outer ones were arranged in this peculiar manner. The figure carries an ebere in the right hand and a spear in the left. This must be the king; a conventional elephant’s head with trunk ending in a hand is carved beside his head and a crocodile’s head beside his left leg. Perhaps the necklace and the spear show him invested with the powers which the captain of war derived from him as their source.

The chief figure in the next group is evidently the king again in a new conception of his character and powers. The spiked headdress recurs. His beadwork jacket is crossed in front by two baldrics; his skirt has a plaited border, like that of the first fish man described. He wears choker and anklets. From his belt hang three masks representing Europeans. A catfish depends from this belt at either side. This, together with the fact that his hands are supported by two attendants, seems sufficient to mark him as the king; there is no reason to connect the catfish with the captain of war.

Next below is a figure with three attributes of royalty: a leopard over his head, a catfish in each hand, and an elephant’s head with the conventional appendage of a hand, grasping an object which may be a feather, beside him on his right. His beadwork cap has short side-pieces, he wears the marks of rank on neck and arms and ankles, also crossed baldrics and a beluku caught up at the side by a leopard’s head mask and with the wide stiffened upward extension.

Museum Object Number: AF5103

Image Number: 643

Another indication of his royalty is that he is accompanied by a nude male figure. The king and the queen mother maintained at their courts a number of boys, so called, of all ages up to forty or thereabouts, who formed a privileged caste of marauders. They went naked until they were provided by their royal patron simultaneously with clothes and wives. This nude figure’s right arm is held bent across his body, the hand grasping a snake the body of which extends upwards parallel with his left side, the tail forming a loop. The head of the snake lies across his thighs, or, more likely, is intended to be shown as holding that part of his body between its jaws, as the instrument and symbol of the king’s power over his boys.

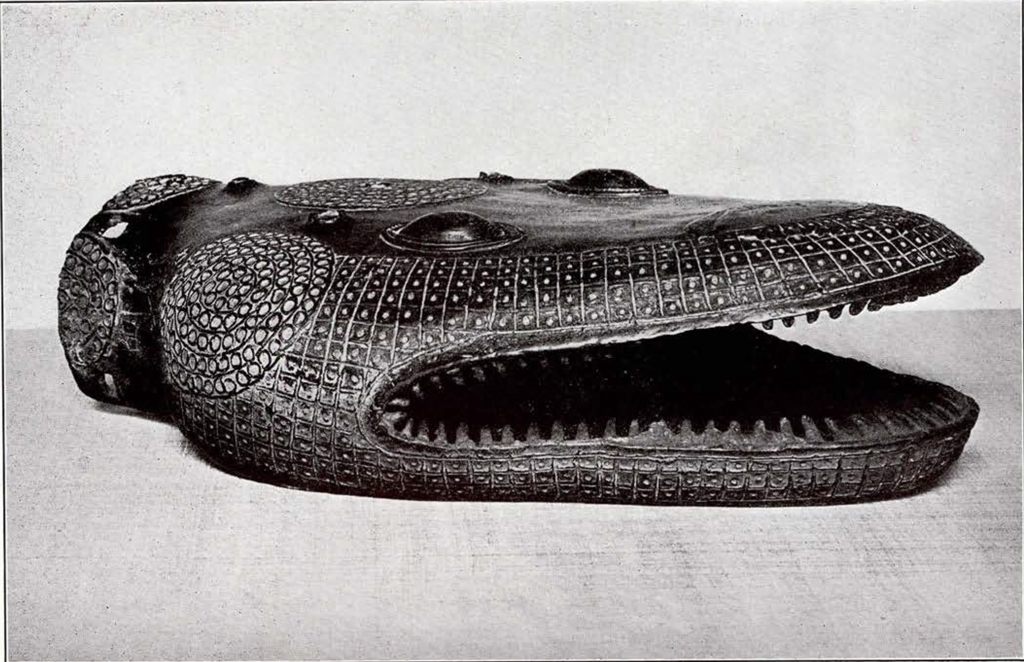

The snake is a powerful juju, and was elsewhere also associated with the king. On the roofs of more than one of the buildings in the royal compound, great snakes of bronze or brass lay head downwards above the doors. This is reported by the Dutchman Nyendael who visited Benin City at the beginning of the eighteenth century. One of these snakes was seen in position by members of the British punitive expedition of 1897. A representation of one of the gates or doors occurs on a bronze plaque in the British Museum, published by Ling Roth [Great Benin, p. 94], in which the snake is shown on the roof. The large brazen snake’s head, Fig. 50, probably belonged to one of these guardians of the royal precincts. “The tribal god [was] symbolized by a python in Benin City,” says A. G. Leonard [The Lower Niger and Its Tribes, p. 279. London, 1906].

Museum Object Numbers: AF5084A/ 21167A / AF2069

Image Number: 638

The lowest group contains two figures in the costume of Europeans of the sixteenth century. The chief features of the dress are a long belted tunic open above the waist in front and reaching to the knees, and long wrinkled hose. The headgear is a round hat with narrow brim, from underneath which at the sides long straight hair falls to the shoulders. The lineaments of the face are differentiated from those of the negro figures chiefly by the exaggeration of the lines of the eyebrows and the bridge of the nose, which are continuous. Europeans are usually represented with beards [cf. Figs. 54 and 55]. Each of these two figures carries in each hand a long pouch or purse, probably containing coins or cowries, as would be appropriate to traders. It is to be remarked, however, that these objects are usually said to be manillas, the horseshoe shaped ingots of copper which formed an important object of trade.

These figures alternate with those of two negroes whose costume differs in several respects from that of the other persons represented on the tusk. They both wear plain round hats with narrow brims, not precisely like those worn by the Europeans, but resembling more nearly the headgear of the bronze figure between the two central tusks. Like that personage each of them also wears a cross on his breast—perhaps the cross of an order, since we know that envoys and compliments and gifts passed between the rulers of Benin and of Portugal in the early years of the sixteenth century. In the case of the central figure of the group, the cross rests on his bare breast, while the cross of the other negro lies on a sort of gorget resembling, except for the absence of the markings which simulate beadwork, the collars of the figures in the third group. Instead of a breast ornament of this nature, the first figure wears something resembling a ruff, but no choker, though high rank is indicated by his anklets, a feature lacking in the costume of the second negro of this group. Both wear the beluku and carry staves with knobbed heads. Each carries also an object which has been variously described as an axe and as a key. In this particular also they resemble the large bronze statuette just referred to. This object is seen also in the right hand of one of the figures in the bronze group, Fig. 47. If this latter group departs from the general rule in depicting an actual scene, a hunting incident, the implement may be a hunter’s weapon, perhaps an axe used in cutting up game. Since primitive weapons of war are usually not essentially different from those used in the chase, the weapon, if it is one, carried by the tusk figures may be a battle axe.

Museum Object Number: AF5106

Image Number: 646

It is to be noted however that in General Pitt-Rivers’s Antique Works of Art from Benin [privately printed, London, 1900], Plate 46, Figs. 363 and 364, shows a very similar object which is described as an iron hammer; and that in W. D. Webster’s Catalogue, No. 21 [Oxford, 1899], Fig. 183 is an apparently identical “implement of wrought iron found in the smith’s workshop” in Benin City. Captain Landolphe, an eighteenth century visitor to Benin, “when speaking of the iron and .copper used to decorate the interior of the houses, says that all artisans who distinguish themselves in their craft receive a patent of nobility” [Ling Roth, op. cit. p. 230]. This passage contains what is, so far as I know, the only intimation, apart from Captain Roupell’s list of Officials, that craftsmen might become persons of official importance. In that case their importance might be great enough to warrant their being given prominent or independent representation in the carvings and bronzes. There is no very obvious connection between an elephant and a blacksmith carrying a hammer, as in Fig. 47. But the hammer, together with the chisel, is an essential part of the equipment of the ivory carver; and it is possible that the figure with the hammer, if it is one, in the lowest row of the tusk carvings may be a kind of signature of the artist who executed them. In this case his relation to the animal which supplied him with his material may have been symbolized also in such groups as that of Fig. 47.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-1

Image Number: 654

As for the crosses about the necks of the two tusk figures, of which the second, not having the insignia of high rank would, on the assumption just made, be an assistant to the more important craftsman in front, the occurrence of the Christian symbol in the costume of these two figures may perhaps find its explanation in conditions implied by the circumstances of the native tradition concerning the workers in bronze. Ahamangiwa’s pupils would naturally be chosen from among Bini craftsmen who were already practised in sculpture; the new master must have been a Christian, and was probably closely associated with the Portuguese missionaries, if he was not one of them. His pupils would thus be directly subject to Christian influences and likely to adopt Christian emblems for their own use.

But this symbol, whether in the particular case Christian or not in its implications and history, was, according to a Portuguese writer of the middle of the sixteenth century [Joaõ de Barros, quoted by J. Marquart in Die Benin-Sammlung des Reichsmuseums für VOlkerkunde in Leiden, p. 52. Leiden, 1913], known to the Bini before the advent of the Portuguese. A certain king, he says, who ruled over a country far distant from Benin in the east, was wont to send to the king of Benin for his coronation certain insignia among which was a cross of brass to be worn about his neck; and the king was not considered as duly inducted into his high office until he was invested with this brazen cross. Among other objects received from the same source was a pilgrim’s staff “in lieu of sceptre” ; and if we are to accept as true the chronicler’s statement, which he reports as having been made to King John II (1481-1495) by D’Aveiro, the first Portuguese visitor to Benin, and the Bini envoys whom the latter took back with him to Portugal, it is possible that we have before us on the tusk a representation of the cross and staff in question.

In that case the figures with cross and staff must both represent the king; and we are confronted with the difficulty of explaining not only the fact that he is represented twice in one group and once without any of the usual marks of rank, but also the significance of either an axe or a key or a hammer being held in the royal hand.

The occurrence of European figures on the tusk may be referable simply to the general influence which the Portuguese had won at court. But it may be pointed out that on the assumption that we have here a symbolic representation of the activities of the royal artists, the presence of Europeans in this particular group is peculiarly appropriate in view of the probable close relationship of the Portuguese to this phase of Bini life.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-7

Image Number: 4998

Museum Object Number: AF5111

Image Number: 649

The reference to the conferring of insignia by a distant overlord, whether or no this suzerainty is to be regarded as a sober historical fact, brings up the obscure problem of the relations of the Bini through their back country with civilized northern Africa towards the Mediterranean and the Nile. To the Portuguese, of course, the suzerain of Benin in the east was none other than his Christian majesty, Prester John, who has ruled at so many different times and places. One of his putative realms, Christian Abyssinia, though not of course as under his mythical rule, Dr. Marquart, in the work quoted above, regards as a possible early religious suzerain of Benin in the days before the African converts of Islam won the negroid principalities of the Sudan for the Prophet.

There can be little doubt that the negro kingdoms of West Africa owed certain cultural features to contact by way of the trade routes leading north and east with the civilized parts of the continent; but that the art of casting bronze by the tire perdue process was known to the Bini before their contact with the Portuguese in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, cannot at present be demonstrated. Sir Hercules Read remarked twelve years ago: “In the case of the panels from Benin [in the British Museum] the style of the art is unquestionably native, while the metal of which they are made has been shown by Professor Crowland’s analysis [Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, XXVII (1897-1898), pp. 374376] to be certainly Portuguese” [Note on Certain Ivory Carvings from Benin, Man, 1910, No. 29]. In view of the part unquestionably played by the Portugese in Bini history four hundred years ago, in view also of the fact that the only marks upon the bronzes themselves which bear unequivocal witness to definite foreign influences are the figures of Europeans of that period, and having regard to the result of the analysis of the metal, it is clear that the burden of proof of an origin other than Portuguese for metal working as a fine art in West Africa rests upon those who dispute the Portuguese claims.

Museum Object Number: 21168

Image Number: 652

Museum Object Number: 21168

Image Number: 653

Since the former Keeper of the Department of British and Medival Antiquities and Ethnography of the British Museum wrote the words just quoted, the only fact that has come to light which might appear to be of sufficient weight to shake this position, was the discovery by L. Frobenius, between the years 1910 and 1912, in an abandoned burial ground in the northern Yoruba country, northwest of Benin, of a head of bronze and several in terra cotta of a high order of workmanship, together with glazed pottery and bits of glass in a condition which seemed to the discoverer to point to the former existence of a manufacture of glass in that country and consequently, of a higher civilization than there is evidence for in any other part of negro Africa [L. Frobenius, Und Afrika sprach, Vol. I, p. 335 ff.].

The founder of the royal family of Benin came, according to Bini tradition, from the Yoruba country and from the very neighbourhood whence this discovery was reported; and if it was possible for a craftsman, probably an armourer of Portuguese or other European nationality, from a Portuguese ship, to reside in tabooed Benin long enough to establish there a school of artistic metal working, as the tradition indicates that he did, it does not seem improbable that the same teacher or his Bini pupils may have been responsible for the communication of the same and of other European arts to the Yoruban kindred of the family reigning at Benin. A small head in earthenware from Benin, in the manner of the older Benin heads in bronze like the one at the left of the altar and those shown in Fig. 39, is pictured in General Pitt-River’s Antique Works of Art from Benin, Pl. 46. There do not seem to be any more important differences between the Yoruba and the older Benin heads than might be sufficiently accounted for by differences of local fashion in face cicatrization and other personal adornments.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-4

Image Number: 660

Museum Object Number: 29-93-4

Image Number: 659

Of the bronze heads, six, representing four chief types, are shown on the altar. Of these the most impressive in point of size and decorative intention are the two which stand one on each side of the group of bells and have the peculiar winglike appendages to the headdress and the still more singular stiffy wired ornaments of large beads which project in front of the face, and the ends of which in one case actually rest upon the eyes. That this stiff forward curve is regarded as essential may be seen in the case of the larger head from the struts which, cast in one piece with the beads and the head, keep the ornaments in place over the cheeks. In the other case the ends are free, and seem to have been cast in the position they now occupy, or bent into it, to prevent their being wrenched sideways or backwards out of the prominent forward position they were originally intended to have. The king whom the British deposed in 1897 wore at his trial one of these winged caps of beadwork, which, as may be seen from the quite realistic representation, are built up of bugles or cylindrical beads of various sizes.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-4

Image Number: 658

The same material was used for the streamers composed of groups of these strung or wired bugles, and for the high collars or chokers. Even such details as the transverse placing of the terminal bead of a string, or the closing of a row with a bead of a different shape are carefully indicated. In one instance the very cord or wire which attaches an ornament consisting of a large cylindrical bead with a curiously shaped small flap depending from it to the left side of the cap on the smaller winged head is clearly shown. Towards or at the back of all the heads on the altar except that at the extreme left, one or more slender plaits, presumably intended to represent hair, hang among the beadwork streamers.

The head last mentioned, together with those illustrated in Fig. 39, is obviously representative of the oldest type of bronze castings. This is seen not only from the character of the fine dark green patina but also from that of the casting itself, the metal being much thinner than in the specimens which show plain superficial evidence of later manufacture, from the finer modelling of this type, and from the presence in the other heads of what are clearly newer decorative accretions and other modifications of style.

The brief period during which impressive products of artistic metal workers were turned out in Benin is, it seems certain, an interpolated great age, so to call it, appearing abruptly and passing through a rapid degeneration to extinction. The products of the brass workers on the West Coast of the present day have little in common with such fine work as is represented even in an already degenerate specimen like either of the two large heads in the middle of the row on the altar.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-5

Image Number: 661

Museum Object Number: 29-93-5

Image Number: 662

Comparison of these with Fig. 39 at once makes plain the differences in the style of modelling, showing how the Bini wood and ivory carvers, as soon as foreign influences had grown weak, applied the methods of their familiar technique almost without modification to their work in bronze, returning to the old stylistic treatment of salient features of the face which the less plastic medium in which they were accustomed to work had forced upon them. Compare the nose and lips of, say, the largest bronze head with the same features of the head at the left side of the altar. In the former they are, so to speak, stuck on, with but little effective effort to obliterate the angles that mark them off from the neighbouring region of the face. The older artist, on the other hand, manipulated the wax with considerable skill in preparing his mould, smoothing out angles so that the sides of the low bridge of the nose merge imperceptibly into the gentle curves of the cheeks. With a deftness of touch and movement by no means unrefined he has shaped without grossness of suggestion a head unmistakably negro—rather as if he had purposely refrained from an exaggeration of traits which in uncontaminated negro art are emphasized without self consciousness. The remarkable prognathism of the face is not concealed, but is, as it were, apologized for by the smoothness of the contours given to it. Even such a carefully observed detail as the depression running back from the outer corners of the orbits to the temples has not been shirked, rather it has been softened. Everything points to a purposeful idealization of a negro type which is not at all characteristic of a negro artist. All this has been forgotten in the later heads in favour of a return to the blunt directness of the woodcarver with, for instance, his traditional trick of turning out noses like fat inverted T’s and mouths composed of pairs of juxtaposed parallelepipeds. His conventions are well seen in the rattle staves (Fig. 42); in the ivory figurine (Fig. 51), in the tusks, and in the casket (Fig. 65) the same characteristics are to be observed.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-5

Image Number: 663

The fading out of European influence is marked by some interesting developments in the later bronze heads. The head on the left is quite evidently less suited to be a pedestal for a tusk than any of the others on the altar. Apart from its rather insignificant size as compared with that of the object it supports, there is too great a contrast between the forward slope of the face and the strong vertical thrust of the lower part of the tusk. This structural error—which was, in fact no error at all, if, as we have seen to be probably the case, the heads were originally not intended to be associated with the tusks in this manner; it only became one with the change in their destination—this fault has been corrected in the later heads in a manner which speaks well both for the ingenuity and the taste of the later artists. The retreating forehead which with the cap is to become the immediate base for the tusk with its steep upward thrust has been itself made vertical, while the characteristic forward slope of the lower part of the face has been preserved, meeting below, however, the long vertical line of the choker, so that the impression received from the whole is of a suitably massive base, the direction of whose long axis is identical with that of the contiguous part of the object which that base has to support.

The choker itself has been greatly enlarged from the simple closely fitting collar of beads, and a flange has been added which gives an effect of greater stability to what has now obviously become, from an object sufficient to itself and independent, a pedestal broad based for the support of the towering ancestral emblem. The elaboration of the headdress with its appended streamers and wings emphasizes the passage from the early realistic phase of the bronzes to one largely decorative in intention.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-2

Image Number: 655

It is only in this sense that the winged heads can be said to be degenerate. They are, in fact, viewed as examples of negro art, more authentic and impressive than the early heads. They represent a return to old methods in a new medium, and illustrate well the naive, bold, and direct treatment of line and disposition of masses by which the negro artist reaches the broad effects he aims at, and by means of which he produces what may be called racial portraits, recognizable and impressive composite portraits, so to speak, of his own racial type. The two heads which flank the central ones on the altar may perhaps be regarded as of a transitional type marking the gradual reversion towards the older conceptions and methods in the treatment of the features of the face, which are modelled more in accordance with those of Fig. 39 than is the case in the winged heads.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-2

Image Number: 657

The flange at the base of some of the later heads carries in low relief representations of various objects which occur on the tusks, on the other bronzes, and in the wood work. Thus, on the flange of the large winged head there appear, on a ground covered with a guilloche ornament, two leopards, a celt, three ox heads, two frogs, two objects the nature of which it is difficult to determine—perhaps they are catfish—and, occurring four times, a bent arm holding a three pronged object.

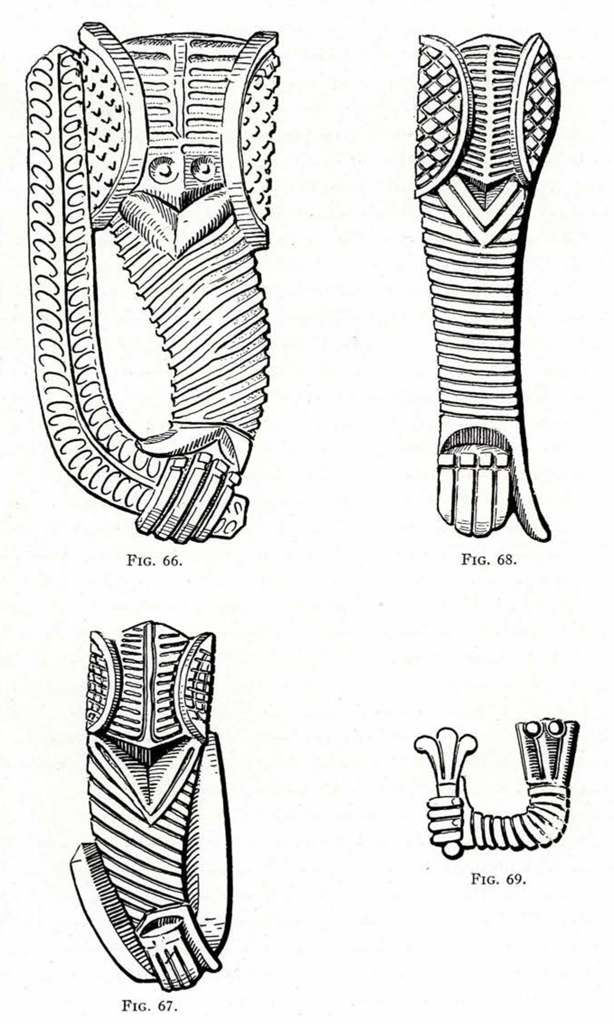

It is possible to show by figures taken from various specimens in the Museum that this bent arm is derived from the conventional Bini method of representing an elephant’s head with its proboscis terminating in a human hand. The nearest approach to realism is seen in the head of the elephant in the uchure (Fig. 42). How this becomes slightly modified in a representation in relief may be seen in the mask in Fig. 49, an example of the peculiar convention referred to on p. 131. A further degree of conventionalization is shown in Fig. 66, a drawing of one of the figures on a tusk now on exhibition in the Museum but not figured here. Figs. 67 and 68, both drawn from the tusk which stands on the larger winged head, illustrate two further stages in the progressive loss of detail leading to the extreme simplification of the upper part of the figure seen in Fig. 69, which is from the flange of the base of that head. The eyes, lost in Figs. 67 and 68, are preserved in the otherwise more simplified form of Fig. 69. Finally only the tusks remain to suggest the origin of a device which is in the final stage of simplification to all appearances nothing but a bent human arm surmounted by a chevron which might be put down as an epaulet if we had not before us the other links in this chain of degeneration. Ling Roth [op. cit., p. 225] calls attention to this transformation but does not illustrate its stages.

This device of the bent arm, the development of which we have thus traced from its beginnings to its final form exclusively within this province of native art, has been derived by M. Buchner [Benin and die Portugiesen, Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie, XL (1908), p. 984] from Morocco, by no direct overland route, but via Portugal and the Atlantic, as a familiar heraldic figure. Herr Buchner is one of the inquirers into the origins of Bini art who will allow to the Bini themselves scarcely any claim at all to a share in these origins.

Museum Object Number: 29-94-1

Image Number: 631

Between this attitude and the position that the style of the bronzes is purely negro—a position that does not seem to me to be tenable in the face of the modelling of the older heads and even of some of the figures of the plaques, notably the legs of the man in Fig. 44, there is a happy mean, the case for which is well put by 0. M. Dalton in his review of Great Benin [Man, 1903, No. 108]: “External influences there undoubtedly were, but they need not be supposed to flow from too many points of the compass. . . . Natives who were presumably skilful in carving wood and ivory would find a transition to a tractable material like wax a very easy matter if they had capable instructors; their best work would be produced almost at once while the effect of the tuition was still fresh. . . . The examination of any large series of castings, such as the panels at the British Museum, does not justify the assumption of a pre-European period, long or short; the very abruptness with which the most admirable work appears on the scene is really an argument for the European hypothesis rather than against it. Indeed one of the three panels in the series which have the appearance of greater antiquity than the rest and are marked by a peculiar restraint of treatment not at all characteristic of purely native art actually represents an European.”

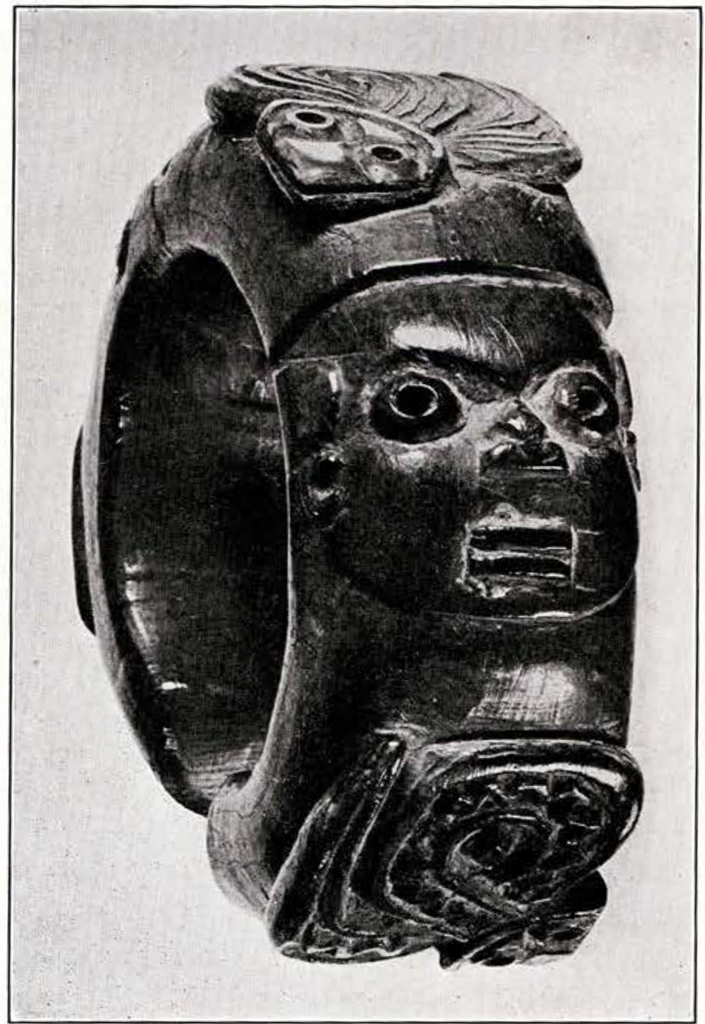

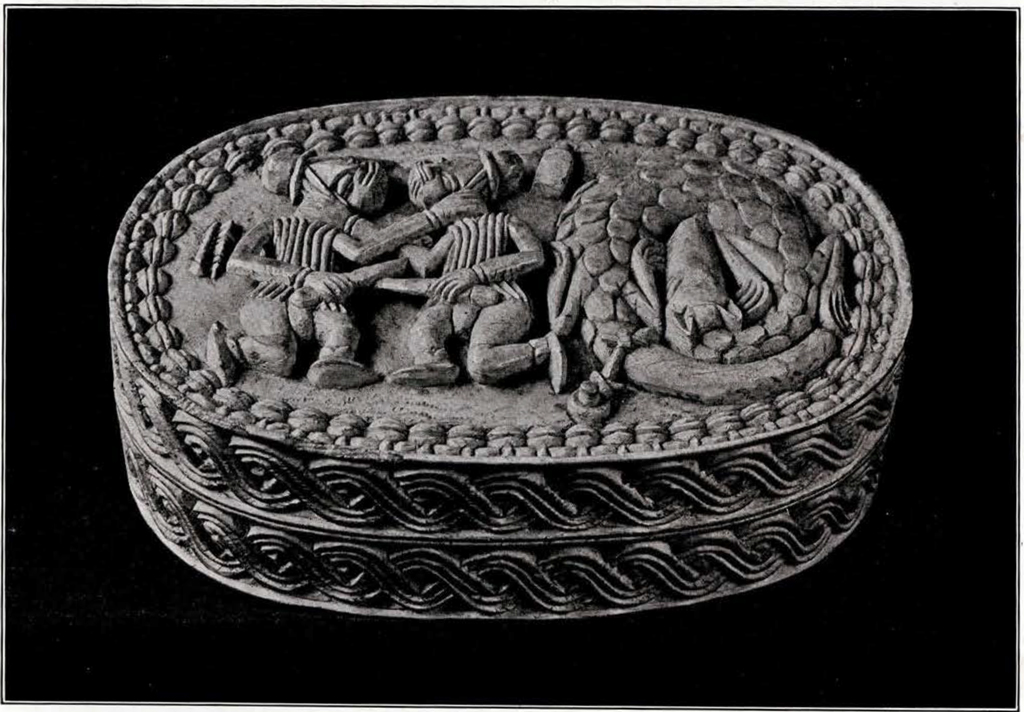

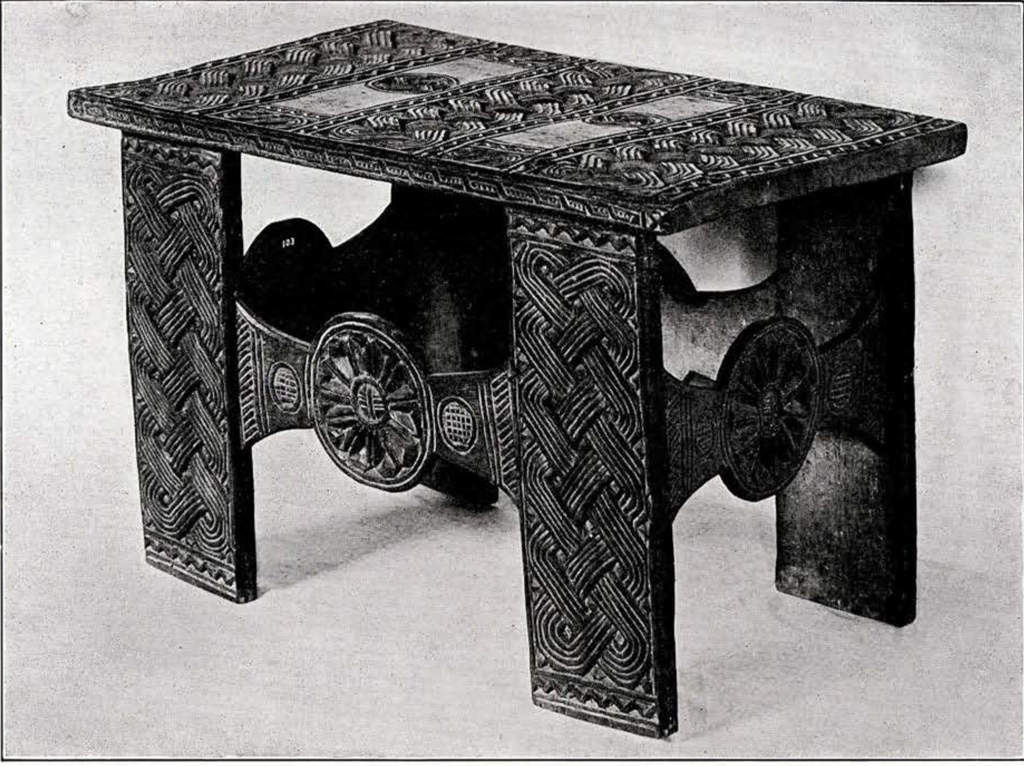

Three especially interesting objects are among the remaining examples of Benin art which are pictured here—a bronze group, an ivory casket, and an ivory armlet.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-6

Image Number: 664

The principal figure of the group (Fig. 48) is a kneeling man. He wears the beluku, his body shows the linear cicatrizations, about his neck is a cord from which are suspended what appear to be four bells, one resting on each shoulder, one on his chest and one on his back. His wrists are bound, his hands held together in front of his body in an attitude of supplication. His legs also are bound or manacled at the ankles. Around his middle is a cord to which were formerly attached, at his back, the ends of two other cords by which the arms of the two female figures behind him are bound. Two other figures of which only the legs remain, and which, judging from the size of these surviving members, were on the same scale as that of the principal figure, flanked, one on each side, the two kneeling females. In front of the large kneeling figure are represented, on the rectangular, much battered base, a crocodile, a tortoise, and between them in a boat shaped receptacle a lashed bundle of indeterminable nature. On each side of this figure along the edge of the base are placed four severed human heads. The group evidently represents three victims ready for sacrifice; such victims were sometimes slain in a kneeling posture, or were allowed on certain occasions to beg their lives in this supplicating attitude.

There is a bronze group in the Peabody Museum at Cambridge, which Dr. E. A. Hooton [Benin Antiquities in the Peabody Museum, Harvard African Studies, I, p. 134] considers as representing “the king and his female attendants standing behind the sacrificial pit, witnessing the decapitation of human victims whose heads and bodies were thrown into the pit.” This interpretation appears to rest chiefly on the fact that there is a “square aperture in the pedestal immediately in front of the king” which is taken to represent the pit into which, as we learn from several accounts, the bodies and sometimes the heads of decapitated victims were cast. But square apertures in the castings with these slablike though not solid pedestals seem in fact to be structural, designed to save metal and lighten the weight of the object. The aperture in the pedestal of Fig. 47 and in those of the bronze cocks previously referred to can hardly be explained in any other way; they can scarcely be sacrificial pits. On the other hand we might, on Dr. Hooton’s supposition, expect one in the pedestal of Fig. 48 from the nature of the scene represented; but it is not there.

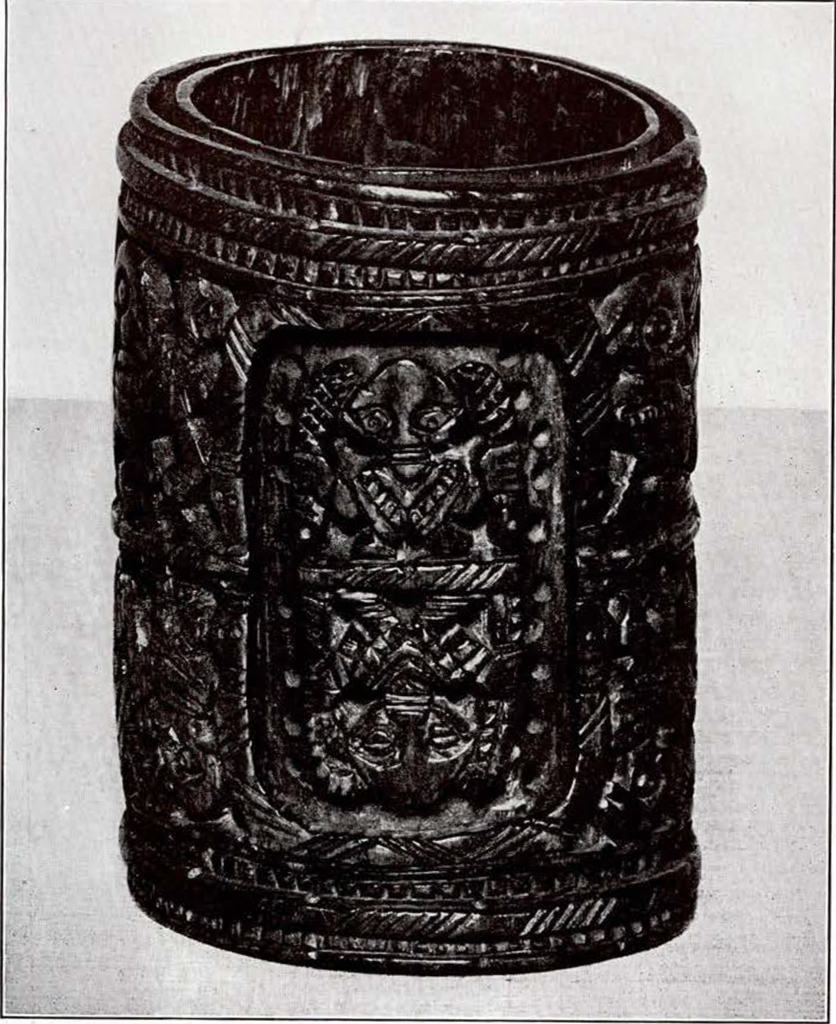

The ivory casket shown in Fig. 65 was formerly the property of Sir Ralph Moor, who was Consul General and Administrator General of the Niger Coast Protectorate at the time of the punitive expedition to Benin. The carving on the lid represents a struggle between two Europeans, presumably for the possession of the pangolin, or scaly anteater, which is tethered to a peg beside them. On the background are carved a square faced bottle, no doubt a factor in the quarrel, and two closely associated objects, perhaps a brace of catfish tied head and tail. A string of cowries and one of beads within the plain moulding round the rim of the lid of the casket frame the picture.

Museum Object Number: AF5101

Image Number: 640

Museum Object Number: AF5101

Image Number: 641

Museum Object Numbers: AF5085 / AF2048

Image Number: 639

The heads of the mutually half strangled combatants have been placed by the carver in his attempt to represent the effects of the struggle so that the long axis of the face is at right angles to that of the body, the bodies being shown in an attitude which is a strange compromise between a profile and a full face view. Curiously enough, this posture of the head is the same as that by which is represented the attitude of Europeans when taking aim with a crossbow, as shown in one of the subsidiary figures on the largest

carved tusk. In the latter instance a leopard is associated with the European, which is also the case with the European figures of the armlets, Figs. 56, 57 and 58. The dreaded beast is evidently an attribute of the redoubtable white man as it is of the king.

Museum Object Numbers: AF5112

Image Number: 650

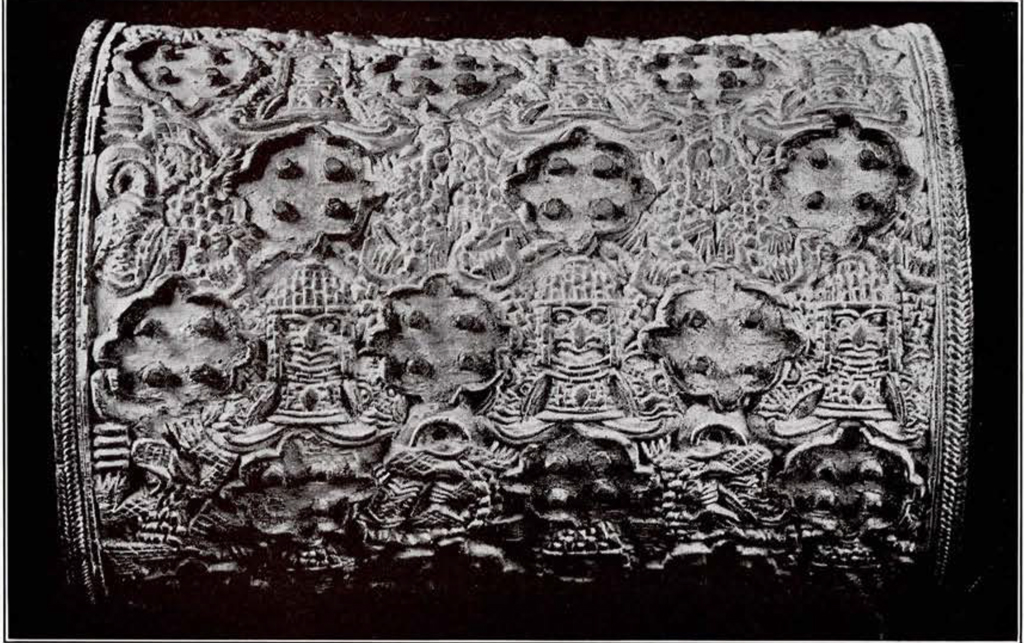

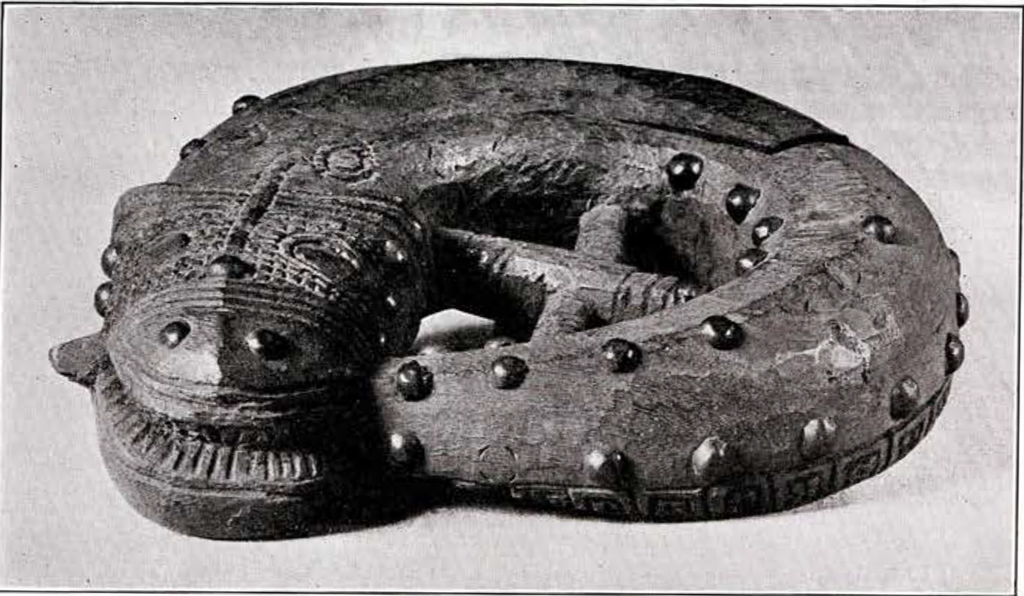

The ivory armlet, Figs. 62 and 63, is a masterpiece of toreutic art. The grotesque mythic figure of the king with his catfish legs is here treated as the principal unit of a decorative pattern. With each hand he grasps the tail of a crocodile. The limits imposed by the narrowness of the spaces between the metal buttons, which have fallen off, involve an extreme compression of curves which would have resulted in an awkward crowding of the figures but for the ingenuity with which the carver has met his difficulties. There are six horizontal rows of three figures each. In two cases the figure is so squeezed between the buttons that the heads of the catfishes have had to be turned downwards, and there being no room for the crocodiles, the hands of the king are also directed downwards to clasp his legs. In two places on the left margin of the armlet a catfish, and in two others a crocodile, are placed between the crocodiles held up by the king and the border of the armlet to fill in small gaps. A human hand issues from the mouth of each principal crocodile along this margin. At the right margin the crocodiles, through lack of room, have had to be cut down to a head and the tip of the tail, but there is no mistaking them for what they are, with such skill has the carver suggested the essentials of form so simply and clearly delineated elsewhere.

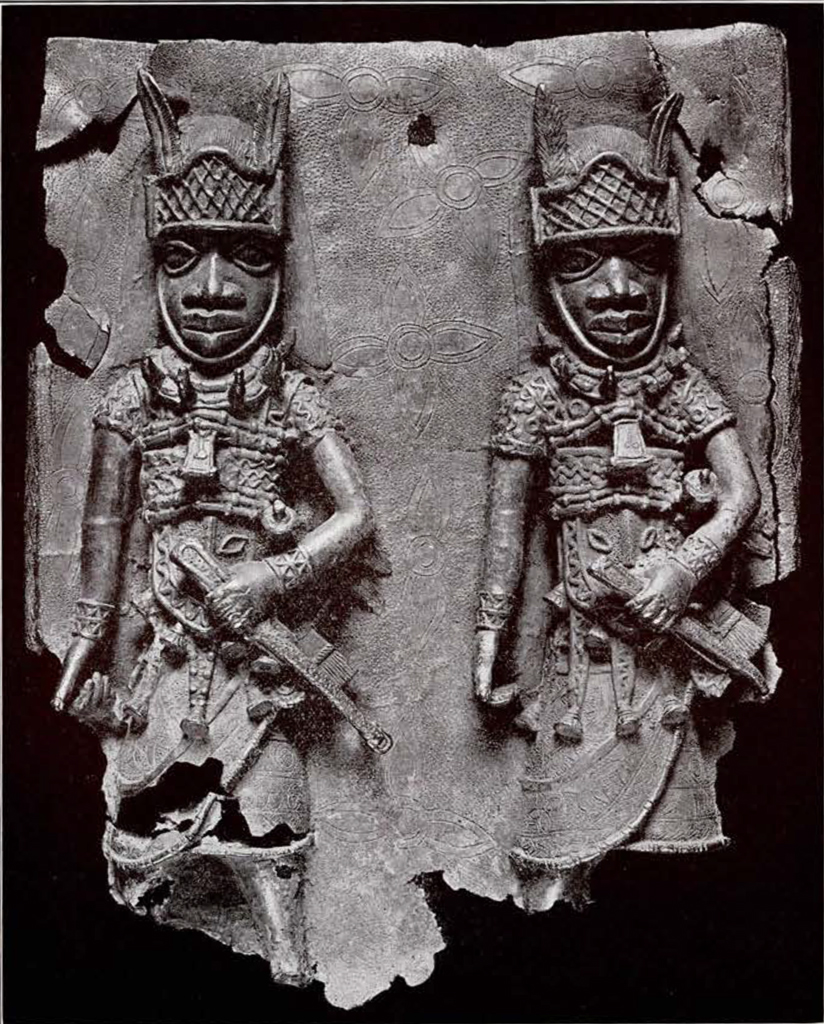

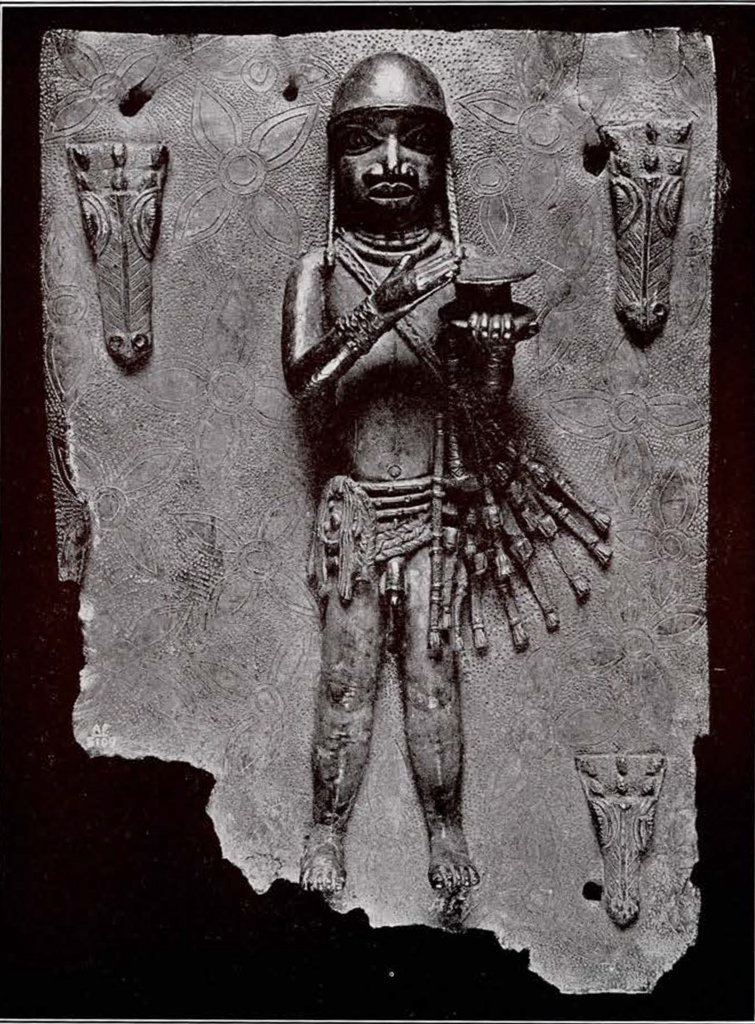

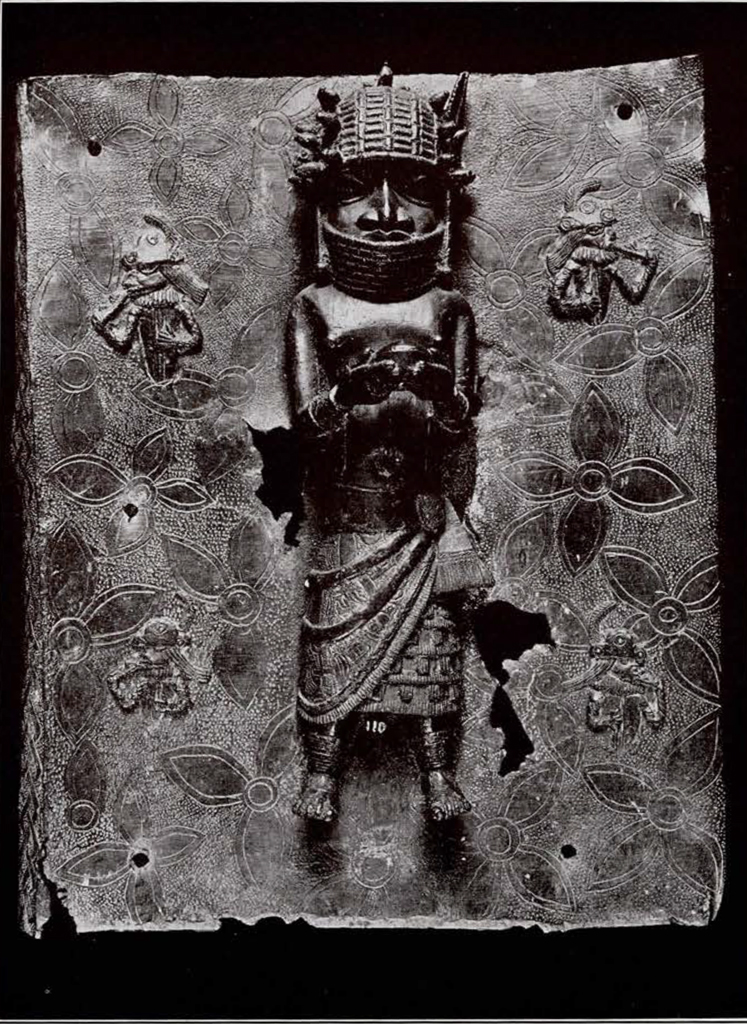

On the plaques, Figs. 32, 43, 44, 45, and 46, which appear to have been used for the adornment of the pillars and walls of the king’s, perhaps also of the queen mother’s, residence, the figures represented are of the same general character as those described from the tusks. The central figure in the largest plaque—the one at the left above the altar—is probably a king, as was pointed out in the discussion of the tusk figures, since he is accompanied by two nude boys. Fig. 45 appears to represent two celebrants at the sacrifice of an ox. Their costumes are identical. The figure on the left, holding the severed head of the ox, has removed his sword with the baldric from which it is suspended and given it to his companion, who holds it beside his own with the baldric swinging. Neither figure has special marks of rank. Their necklaces of leopards’ teeth may indicate that they are of the following of the captain of war. A fragment in Fig. 49 shows a figure carrying in one hand a single wand, in the other three. These are probably the king’s taboo wands, referred to in the description of the tusks. All the plaques have a foil ornament engraved on the background. In the case of Fig. 46, in addition to the heads of Europeans engraved on the beluku of the figure, there is in low relief at each corner of the plaque the head and torso of a European with long hair, wearing a ruff and doublet, and, apparently, blowing a horn. The feathers worn in the caps of some of the plaque figures may have a religious or fetish significance. Certain fetish chiefs and priests in the Benin country wore feathers as a part of their headdress ; and we have seen (Figs. 49 and 66) that they are carried by the fetish elephants.

H. U. H.

Museum Object Number: AF5109A

Museum Object Number: AF5113

Image Number:651

Museum Object Number: AF5078

Image Number: 635

Museum Object Number: AF2038

Image Number: 610

Museum Object Number: AF5074

Image Number: 632