On May 22, 1925, there was opened to invited guests of the Museum an Exhibition of Chinese Art which included many examples of painting, sculpture, bronzes, and pottery not hitherto seen in this country. Charles Custis Harrison Hall was entirely rearranged and the new objects placed not only so that their own beauty could be fully appreciated but so that the beauty of the others was greatly enhanced. On the day following, the exhibition was opened to the public and the new accessions became a part of the permanent display of Chinese Art in Harrison Hall.

Conspicuous among the newly acquired objects that have attracted attention from the opening of this Exhibition, are the pottery mortuary figures corning from graves of the T’ang Dynasty and representing horses, camels noblemen, officials, guardians, royal or noble ladies with attendants, dancers and musicians. The purpose of these notes and illustrations is to present to the readers the MUSEUM JOURNAL these exceptionally flue groups of Chinese works of art in a clay medium, The Museum has for several years possessed a number of similar, though smaller, mortuary figures.

Image Number: 1609

Visitors familiar with the Chinese Collections in the Museum may recall in particular among these earlier accessions a group of nine little ladies in procession, carrying musical instruments or wearing the long narrow sleeves that formed part of the dancing costume. These with other ladies very elegantly dressed and with elaborate and peculiar coiffure indicating their age or condition in life, Buddhist priests, officials, guardians, horses and camels, prepared the minds of visitors for the much larger and more striking groups that have been but recently added, and that it is the purpose of this article to illustrate and describe.

One of the most interesting of these latter groups, although the dimensions of its individual figures are dimunitive and the scale much smaller than in the groups illustrated here, has been published already in the MUSEUM JOURNAL for December, 1924, just after the arrival of the set at the Museum. In that group a royal or noble lady stands, tall and dignified, gowned in elaborate robes, and attended by two kneeling child figures. Before her bend two dancers in graceful attitude while beyond are three more little ladies playing musical instruments. The exquisite grace of the figures and the childlike naivete of the group as a whole make a strong appeal to people of all ages. These figures have no trace of glaze; the hair, shawls and striped skirts are painted with red and black pigments. On the robes of the lady are elaborate borders painted to represent brocade, a feature appearing on four of the figures pictured in this number of the JOURNAL. The sculptor’s art represented in these tomb models reaches its culminating point in the life size statue of a Lohan acquired by the Museum in 1914 and published in the MUSEUM JOURNAL for September, 1914. This statue is not a mortuary figure but is so closely related to the tomb models, both in technique and material, that it should be mentioned as showing to what grandeur this glazed pottery sculpture rose during the T’ang Dynasty Technically and artistically it ranks as one of the greatest works of art known. While so much Can hardly be said for the grave figurines, many of them are quite worthy of the great esteem in which they are held as works of art of a very high order.

Little is known of the development and history of the tomb figures. Most of the finds which at present make up the collections in various museums have little or tic data to accompany them. We do not know how they were found, how arranged in the tomb, whose tomb it was, or what other objects were associated with them.

Image Number: 1607

We have learned much about ancient Chinese burial customs from evidence afforded by Chinese literature and from the accounts of missionaries and travellers. Even in very early times, it was the custom to place the coffin in a sepulchral chamber, together with the things desired by the deceased for his existence in the next world, and over this burial room to heap a great mound of earth. Every year the descendants were expected to add a little more earth to the pile so that, theoretically at least, the most remote ancestor would be honored with the largest mound in the group of family graves. Some of the mounds had avenues of pillars and carved figures leading up to them; many were guarded by stone lions seated at either side near the tomb door, which was a false one of stone engraved with designs of dragons and demon kings. As for the furnishings of the tomb, there were times when the articles became very elaborate and costly, and, as exhibitions were held before the burial, families vied with each other in their efforts to make the funeral very impressive. Laws were made at various times with the hope of curbing undue extravagance but always there was enough spent to keep great numbers of potters and other artisans working on grave furnishings alone. Literature has provided us with detailed lists of the things buried with the dead. One list, written in the Later Han Dynasty, mentions many pots, hampers, and jars of food and drink, ninety pieces of pottery for the stools, tables, weapons, armor, carriages, garments, musical instruments, bells, and a very interesting item—thirty six “images of men and horses.”

It was the custom in very ancient times in China, upon the death of a prince or high official, to bury alive or sacrifice at the grave, those persons and animals whose spirits the departed had wished to have accompany him into the next world. Thus, not only horses and camels, oxen, swine and birds were buried in the tombs, but even some of the ladies of the household, male retainers, actors, musicians and dancers. Confucius made a protest against this cruel custom and gradually it was abandoned in favour of clay images as substitutes. Small Clay figures are found in graves dating from about 200 B.C. and from that time on until the end of the T’ang Dynasty such figures were used. After that wood became the fashionable material. Some of the most delightful of the clay figures are said to date from Han times but the art of the grave potter reached its height during the T’ang Dynasty.

Image Number: 1608

Reliable scientific evidence for the dating of the clay figures is, as has been implied, lacking, yet there can be no reasonable doubt that most of them are of Tang, After T’ang, such figures were made of wood, Some of the tomb groups that have made their way to Europe, a very few it is true, are accompanied by the stone inscribed tablets said to have been found with them and giving the name, history and dates of the deceased. Unfortunately, the connection of these tablets with a particular group of figures rests upon no sure foundation of knowledge, although the available information may, in some cases, be correct enough. We cannot always he certain from what provinces in China these groups are derived and indeed almost all that information is lacking, which is a matter of record where excavation is conducted under proper scientific auspices. This is a condition that may be corrected in the future. In the meantime, the best evidence we have for thy dating of these tomb figures is their similarity in every way to articles kept in. the Japanese Treasury called Shosoin at Nara. The Emperor Shomu left by will all the contents of his palace as a gift to Buddha, to be housed in a special building in the monastery rounds. This unique museum was erected in 749 A. the year after Shomu’s death, and all the articles from his household placed therein and carefully inventoried. There today we can still see them and compare them with the original catalogue. A great many of the articles were imported from China and there are objects identical with ones taken from Chinese graves, the same in clay, in glaze, in design, in tech¬nique. They cannot be later than 749 A. D., when they were put into the Shosoin, arid the probabilities are that they are not much earlier, as they were the latest and finest things imported from China for the Emperor’s personal use. Again, Buddhism did not become popular in China before the fifth and sixth centuries and this fact alone would place those finds which show Buddhistic influence in a period following.

The new groups in the Museum are of the recognized T’ang types and therefore belong to the period between 618 and 906 A. D. They are the substitutes for the persons and animals which, under the more ancient customs, might have been sacrificed.

The quaint charm of these figures lies partly in the simplicity of art structure and partly in the directness and unconscious humour the character portrayal. Nearly every figure is constructed upon a few rhythmical lines and modelled with the greatest simplicity of plane. The character is caught with a few strokes, as painters say. The fire and spirit of the horses, the mournful languor of the camels, the dignified selfcomplacency of the high officials, the haughty elegance or coquettish grace of the little ladies, all serve to delight and fascinate us. Although fashioned in moulds, with details added later, many of the figures have an individuality that is striking. Some of the smaller ones have been compared to Tanagra figurines, but even here we find many that are persons, not types. Among the larger Tang figures the art certainty reaches occasionally the heights of portrait sculpture.

History plays a strange and ironic trick on us when it compels us to seek in the abodes of the dead knowledge concerning the life of a people. But so it has been all over the world, in Crete, in Greece, in Babylonia, and especially in Egypt. It is the same in China, The contents of tombs are the evidence from which we learn of the everyday life of long ago, the dress, the cooking, the music, the dancing. Ceremonies are depicted here the relationships in great households, preparations for travel or the hunt, pets and beasts of burden, even the dwellings. In this connection attention may be called to the earliest piece of pottery in the MUSEUM’S collection, the model of a Han house with tiled roof, balconies, and figures standing at the windows.

It is from grave finds such as these in this MUSEUM and other well known collections, from objects yet to be excavated, from the thousands of still untouched tombs in China, and. from Chinese literature arid records of those times that we shall eventually he able to picture clearly the daily life and customs of the people in the eras of Han and of T’ang.

Painted Pottery Group Representing A Princess And Two Ladies In Waiting

This is a most unusual tomb group and one which delights us with its naive expression of conscious dignity. The mistress, a large woman or rather dominating personality is seated upon a stool of peculiar hourglass shape, while her attendants stand proudly on either hand. The figures are of soft white clay covered with bright unfired pigments worn and flaked by time. The royal lady wears a skirt of emerald green, the thick folds of which stick up above the high belt. Her kimona shaped blouse with its wide sleeves is vermilion and is trimmed with elaborate borders representing brocade in green and black floral forms on a cobalt background. The bright red of the jewel in the front of the headdress and the vermilion painted lips are in striking contrast to the pale creamy flesh tones and the weathered black of the hair. The face is soft and round, with the finely shaped forehead and delicately moulded features of a lady of high birth and station.

Image Number: 1606

The attendants, on the other hand, are not high bred ladies, nevertheless they have the poise that proximity to nobility engenders. Their skirts are vermilion, over hill frilled petticoats of striped green and red, and their blouses are emerald green. Their funny tittle faces are painted a pasty pink quite different from the creamy whiteness of their mistress’s complexion. Both maids have their hands clasped under bright colored napkins (it was a sign of respect to keep the hands covered in the pretence of a superior). They were evidently originally supporting some objects which have since disappeared leaving only the slot like holes in the tops of their clasped hands. Perhaps they held the poles of canopy, or banners, perhaps large flowers, or screw emblems of rank. Their robes also show wide painted brocade borders in green, red, blue and black. Each of the three figures has a narrow border of plain gold around the neck of her robe.

The pattern of the brocade borders shows close of to the decoration on some of the T’ang jars and bowls which are well known. The tang skirt with high waist line and flounced bottom, the peculiar headdress, and the shoes with turned up toes and rosettes are all typical of the Tang period. It will be noted that the feet are normal in size for these figures belong to a date before the custom of foot binding had become prevalent, if it was practiced at all.

A Painted Pottery Horse Richly Caparisoned

Museum Object Number: C469

Image Number: 1571

Of all the figures made for the graves of notables during the Tang period none can surpass the models of horses of which a number have come to light in the last few years. Some are represented in spirited action, pawing the ground or with neck arched as if pulling at a halter. Others, as in this case, are represented standing quietly, but even then there is a machine of movement, conveyed perhaps by the directness and simplicity with which the ancient potter recorded his impression.

This horse is of the fine white clay, like pipe clay, so commonly used for the figures. There is no glaze, but the figure is painted with rich unfired pigments, the body a dull brown red, almost magenta, and details of the trappings picked out in emerald green, black, vermilion and dark red. Mane and tail were Jest in the biscuit.

It is the saddle cloth that is most striking. Thrown over the saddle and completely covering it is represented, in painted clay piece of bright vermilion cloth with gorgeous brocade borders, a wide central stripe crossing the middle of the saddle. Again, as on the garments of the royal lady and attendants, we see floral forms related to the designs on T’ang food bowls, again the colors are emerald green and vermillion, and the outlining in black. Here, however, the background of the brocade border is gilded, giving a very rich effect. The large round red pompon on the rump, the gay gilded one striped with dark red at the throat, and the ends of the gold bit showing at the corners of the pink mouth complete the picture of a nobleman’s mount of the days of T’ang.

Glazed Pottery Horse

Museum Object Number: C467

Image Number: 1567

The statuette is covered with glazes of the well known T’ang type. The body is a warm amber varied by streaks of the leaf green which has run down from details of trappings and tassels. Mane, tail, and hoofs are warm cream glaze. The under saddle cloth is quite long and is of mottled green and cream, while the top saddle cloth shows mottled amber, green and cream. A plain green cloth is drawn over the saddle and knotted at each side. It is to be noticed that on none of these figures of horses are the stirrups depicted.

The breed of horses represented by all these tomb models is the Bactrian, a massive type with slender legs which was first imported into China in the second century B.C. Its superiority over the small stocky Mongolian pony was readily seen and by the T’ang era the Bactrian horse was to be found in the stables of all the nobles and well to do throughout the empire. It never entirely supplanted the Mongolian breed, however and the latter is still common in China.

Glazed Pottery Horse

Museum Object Number: C468

Image Number: 1568

This is a delightfully lifelike figure of a Bactrian horse from the tomb of an important personage. The clay is white, rather coarse and hard, and is covered with a warm cream glaze. Trappings have been picked out in leaf green glaze and tassels are amber, as is the mane also. The anther has run down ire streaks here and them from the tassels. Saddle cloths, upper and under are mottled in green, amber, and cream glazes while the cloth tied over the saddle and fastened by a long hand at the side is of plain amber glaze. It is a particularly Iovely piece in color and the faint crazing, or minute crackle, of the glaze, the slight iridescence noticeable on the flanks, and the flakes of buff clay still clinging to the legs lend a mellowness that is very pleasing.

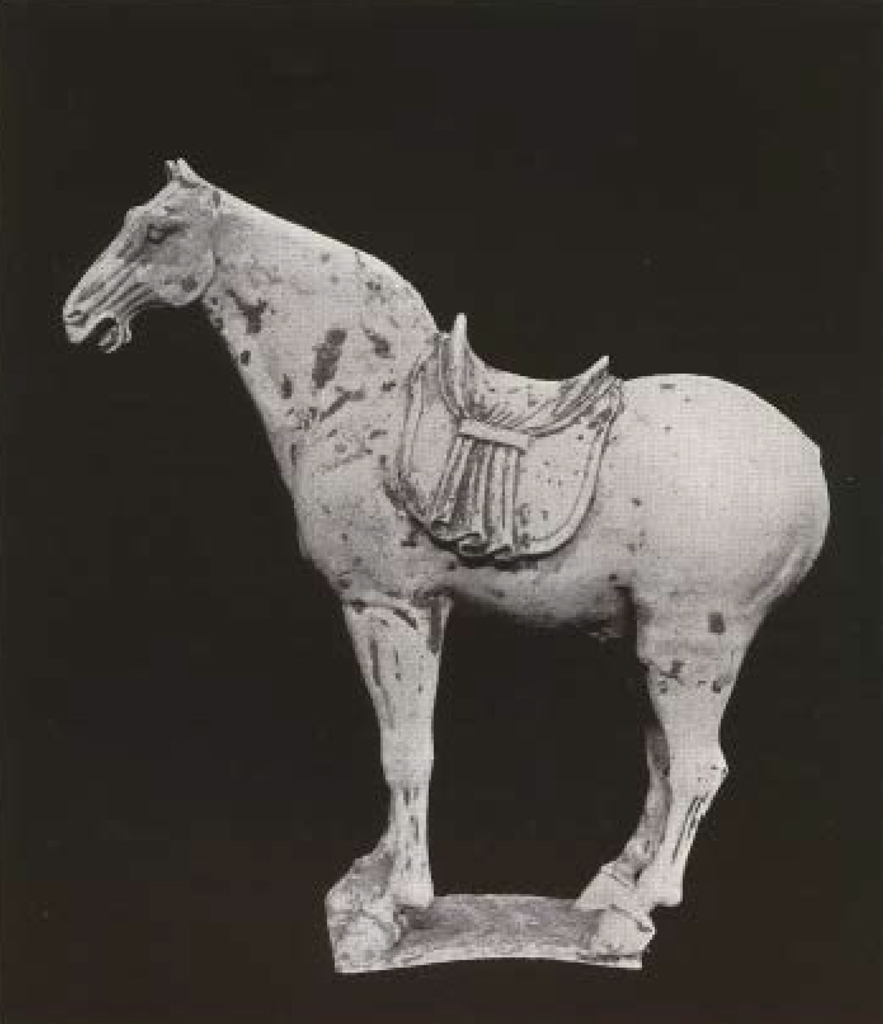

Unglazed Pottery Horse

Museum Object Number: C694

Image Number: 1569

The horse represented in this model is moulded of the very pale pinkish buff clay often used for these figures. This model was originally painted, but the unfired pigments have worn off, leaving only traces of a blue gray on the body (most noticeable on head and neck), a pink lavender on the chest, and the familiar vermillion on saddle and base. There are no trappings other than the saddle and saddle cloth. Even the mane and tail are missing, a groove along the neck and a hole for the tail showing, however, that these details were probably to have been added later — perhaps real ones, of genuine horse hair. Blotches of a sticky yellow clay from the burial may be seen clinging here and there to parts of the model.

Most of these mortuary figures were made in moulds and sometimes the seams are visible. The legs of the animals, for instance, were always made separately and then carefully fitted on the body. The joining can be made out more distinctly in the case of those unglazed models than in those covered with glaze. The bodies of all the figures were made hollow and the animals have large holes under the belly, a device for greater safety in the firing.

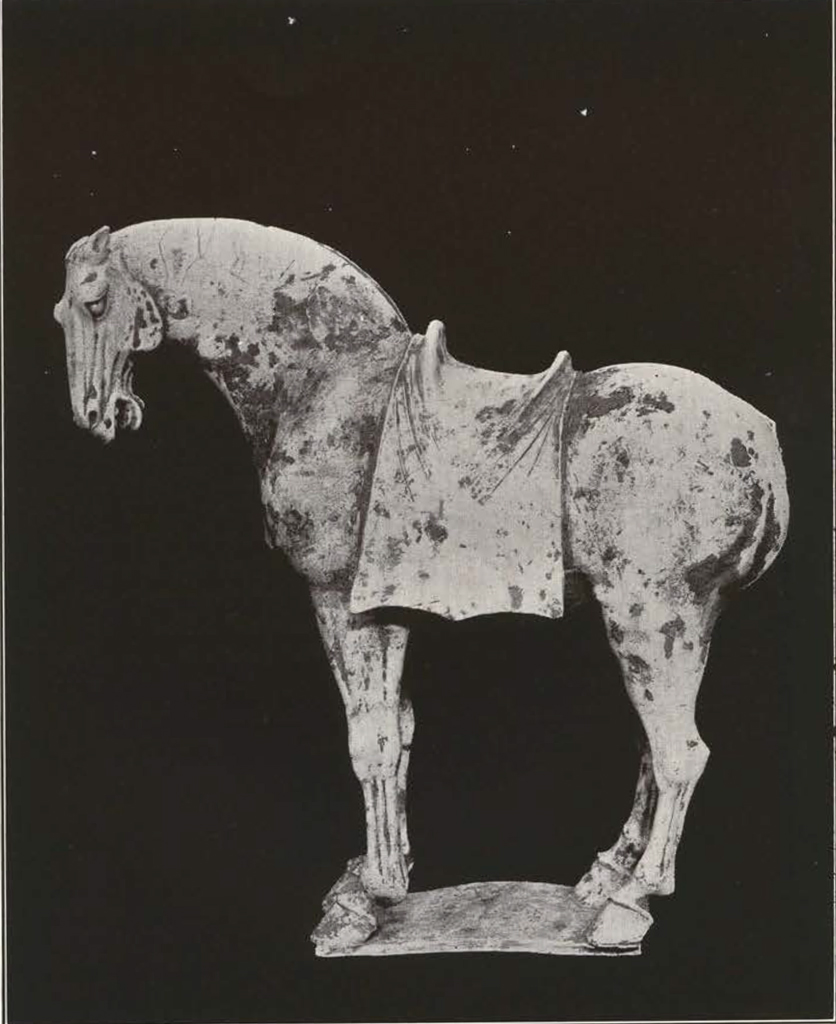

Unglazed Pottery Horse

Museum Object Number: C695

Image Number: 1570

This horse is of the same type as the preceding one and also is unglazed, the natural buff of the clay being quite in evidence. Originally in this case, also, pigment was used freely but as it was not fired this paint has worn or flaked off leaving only traces. Sticky yellow clay from burial is still clinging in grooves or on protected parts of the horse.

The body must have been a rich brownish red and traces of dark gray on face and nostrils seem to indicate that the head was painted a darker colour. Hoofs were black — or indigo — while the flat rectangular base was a bright vermilion. The figure was a very gay one when it was new. This horse has no mane or tail but, as was true with its companion, the groove and hole for their attachment are plainly to be seen. Here there is a small hole in the rump just where a pompon would be placed on the crupper, a detail that leads us to suspect that the figure was intended to bear trappings of some perishable material, long since disappeared, if they ever were present at all.

Mr.Laufer has called attention to the fact that the horses found in graves in Shen-si province are usually of this bare type without other trappings than a mere saddle, while horses from Honan province are usually represented fully equipped, except for stirrups.

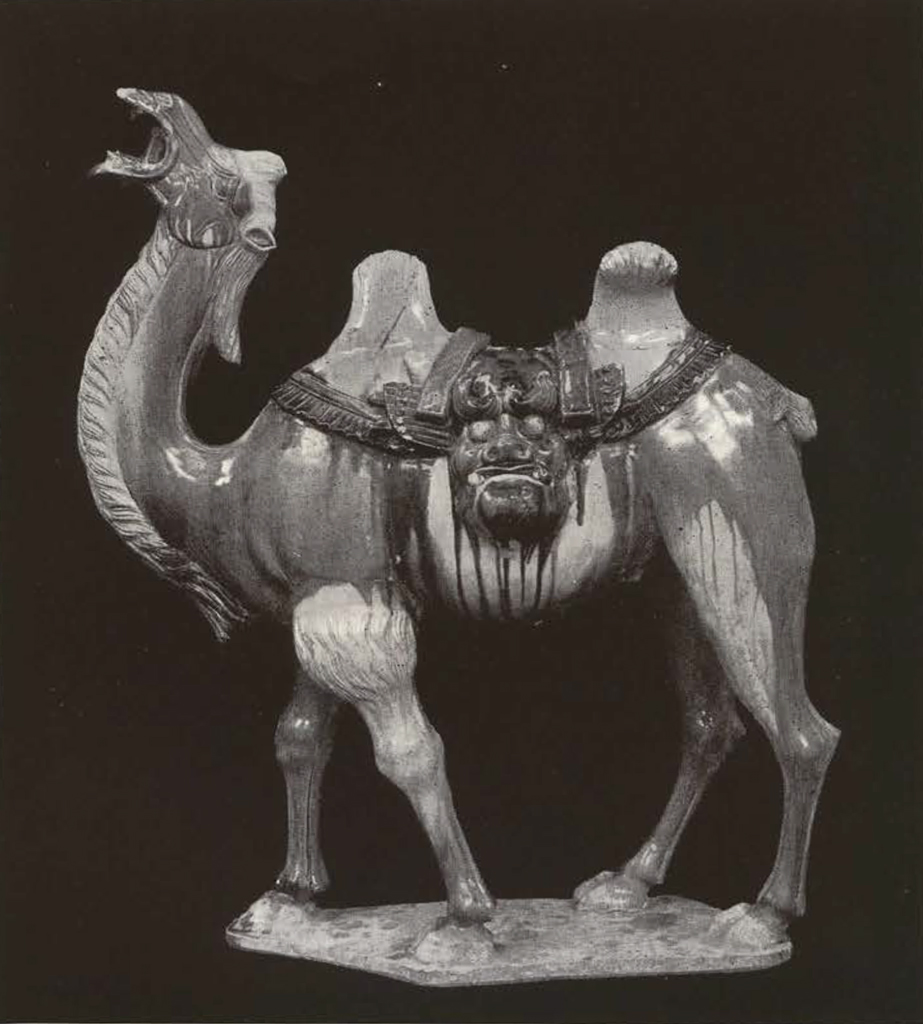

A Glazed Pottery Camel

Museum Object Number: C466

Image Number: 1576

The Bactrian, or two humped camel, was introduced into China about the same time as the Bactrian horse. Small models from tombs of the Tang period have been familiar to us for some time, but such large and fine figures as the two now acquired for the University Museum have until recently been quite rare.

This model is covered with cream and amber glazes. The ruffle of the saddle cloth is leaf green and the pack covering is in the shape of a monstrous animal head glazed in amber, cream, and green, the glaze from which has run down in streaks around the camel’s body. The pack saddle is of the same type as appears on a camel in the Eumorfopoulos collection and on a somewhat smaller camel in the University Museum.

The glaze is minutely crazed and shows iridescence from burial. There are remains of an incrustation of pinkish clay on several parts of the body.

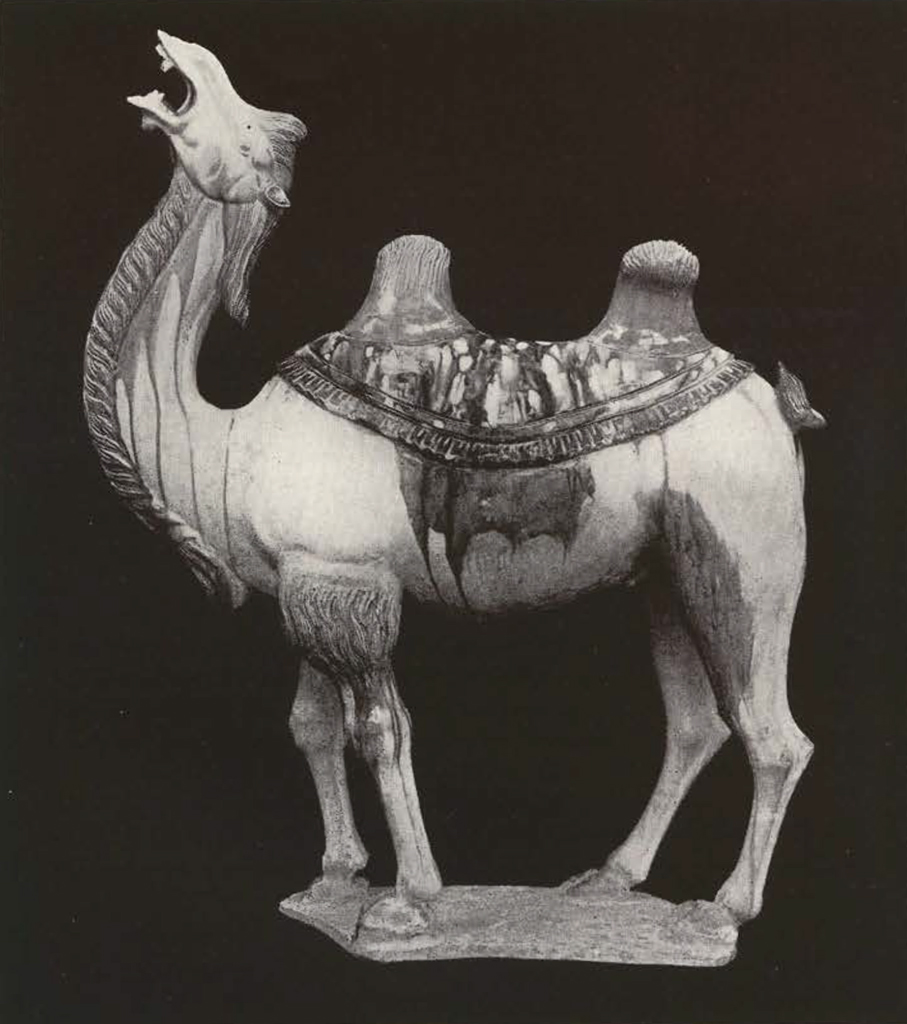

A Glazed Pottery Camel Without A Pack

Museum Object Number: C465

Image Number: 1577

The second of the two large models of Bactrian camels is almost exactly like the other but without a pack. There is only the large oval shaped saddle or pack blanket with its two holes for the humps.

The body of the camel is a warm cream color with the glaze minutely crazed. Hair, humps, and tail are of a deep red amber glaze and there are streaks and splotches of it on the cream body. The saddle cloth is ornamented with a mottled decoration of amber, green, and cream most typical of food bowls and jars found in Tang graves. There is much iridescence. These figures are exquisitely modelled and the outstanding features of the animal caught with true simplicity.

Group Of Four Mortuary Pottery Figures

As usual, the provenance of this fine group of figures is unknown, the only data available merely showing that all four come from the same grave. Here, as in the models of horses and camels, we reach the heights of the T’ang potter’s art. Again we have the most striking character portrayal, for no one could doubt that the two central figures represent individuals of decided personality, probably men of importance whose spirits the master of the grave thought quite indispensable to him in the next world. The outer figures are, of course, of Lokapalas or Buddhist Guardians, whose business it was to frighten all evil spirits away from the tomb. The base of each figure is made to represent rocks.

Museum Object Numbers: C462 / C463 / C464 / C641

Image Number: 1598

The guardians or Lokapalas were, naturally, mythical creatures and therefore depicted according to a set type of attitude, expression and costume. Not so the two central figures. Here the potter is seen as a sculptor of real genius who is able to express by the simplest modelling and most direct manner the characteristic qualities of the individual he is portraying.

It is interesting to compare this group with the one acquired in 1924 and published in the MUSEUM JOURNAL for December, 1924, a group consisting of one Lokapala, two officials, one horse and one camel.

The three illustrations following will show these figures in greater detail.

Pottery Figures Of Two Officials In Long Gowns And High Headdresses

That the four figures which compose this group came from the grave of some princely personage seems evident when we consider the two statuettes of officials here presented. They appear to represent men of rank and position, perhaps advisers, ministers of state, or priests connected with some form of worship. At present this type goes by the name of “official” or “minister.” Doubtless the details of dress, especially the forms of the high hats, would tell us directly of the identity of these gentlemen if we knew more about T’ang costume.

Museum Object Numbers: <aC463 / C464

Image Number: 1600

</a

Both figures would seem to be portraits and each has a feature which strengthens us in this opinion. The figure on the left portrays a man whose left hand has been cut off, and the stump is concealed by the sleeve. The official on the right has decided peculiarities about the eyes and has a strange hump on the back of his neck besides. Perhaps they were court characters of their time. Certainly we can imagine the first as a fat, stupid, lazy man, sensual and cruel, the other the court wit, quick of temper, and with a keen sense of humour, a satirist surely.

The figures are glazed except for the heads and headdresses, which were originally touched up with unfired pigments. The one handed man wears an upper garment of plain yellow amber running to dark brown on his right side. The borders are of dull mottled leaf green glaze. There is a slot like hole in the hand at the belt showing that the figure originally held something—a staff with an emblem of rank perhaps. The long skirt is cream colored, into which run streaks of amber and green from the colored glazes above. The shoes with their turned up toes are green.

The Jester is the more energetic and graceful man of the two and the coloring of his robes is more beautiful. Here a rich cucumber green predominates, covering the upper garment entirely and running down onto the cream skirt in streaks. Only the borders at neck and sleeves are of amber mottled with cream. The shoes are of the cucumber green. The folded and covered hands have the same kind of socket above as is seen in the right hand of his companion.

Food bowls of the T’ang period, some of which may be seen in the Museum collection, show these same glazes, mottled in the same way.

The glaze on both figures is very minutely crackled. A faint iridescence on the lower parts of the figures reminds one of the long burial in the mounds from which they have so recently been released.

Glazed Pottery Figure Of A Lokapala Or Buddhist Guardian

Figures like this were supposed to protect the graves from attacks of demons such as the one here being trampled under foot. Buddhists believed that there were four such demon kings, one to guard each quarter of the Universe. From early Tang times it became the custom to put models of at least one or two of these Lokapalas in the grave with the other figures. Dressed in armor over flowing robes, standing in attitudes of fierce menace, and with glaring expression, they were well calculated to strike terror to the heart of any grave intruder.

Museum Object Number: C461

Image Number: 1597

This Guardian wears a helmet made to represent a phoenix bird whose head, wings and tail rise in a high crest. The armor is of the sheet variety, a type which, as Dr. Laufer points out, was probably never used in China but remained merely an artistic motive introduced from the west along with the Buddhist figures themselves. It is elaborate armor consisting of large breastplates and dossière connected by leather straps over the shoulders, the two breastplates joined in front under a leather strap which is buckled to a wide leather girdle. Over a short full skirt of cloth, glazed in amber, is a shorter divided skirt which probably represents plate mail, for along the lower edge may be seen what resemble a row of laminæ. Plate armor was the type worn in China from early Tang to Manchu times. Leather or padded cloth was literally lined with hundreds of small iron or steel plates.

The upper sleeves are fashioned like great dragon heads out of whose mouths emerge the arms clothed in double sleeves. Legs are encased in greaves and the shoes are large and pointed. The demon upon which the Guardian tramples throws up one arm with its ugly three clawed paw and bites savagely but to no avail at the heel of his conqueror.

Head, headdress, and hands are in the biscuit, that is, the unglazed pottery; the rest of the figure is covered with the characteristic amber, straw yellow, leaf green, and cream glazes with the usual mottled effect. There are traces of pigment on the face and helmet, the lines of black representing beard and mustache being most clear. The upraised hand is pierced, probably for a lance or spear of wood or some such material which has long since perished.

Glazed Pottery Figure Of A Lokapala Companion To The Other

Museum Object Number: C462

Image Number: 1599

The second of the two Guardians is, if possible, more fierce in aspect than the first. It is similarly treated, the glazes covering the whole figure with the exception of head, headdress, and hands. The hair shows in this one, under the phoenix bird helmet, and a small goatee appears upon the chin. Again the upraised hand is pierced to hold a lance made of some material other than clay.

Probably most famous of all Guardian figures known is the clay Mace Thrower in the Sangetsudo at Todaiji, Japan. It is a solitary figure, without a companion. In the same temple are four very fine life size clay figures of the Shi Ten O (the Japanese term for the Four Guardians) and these guard the altar in the Kaidanin. These five Japanese statues are contemporary with the tomb figures we are presenting and we can see that Professor Fenollosa struck very near the truth when he wrote, in 1913 before much was known of Chinese T’ang sculpture, “It is probable that in these fine statues we have very close approximation to Chinese originals; and we can therefore feel that we are in them virtually studying the art of early T’ang.”

It is to be remembered that all figures of Guardians do not necessarily belong to the group of the Four Lokapalas. There were, earlier still in Buddhist iconography, two Dvârapâlas, guardians who held thunderbolts and acted as door keepers. Some say their origin can be found in figures of Indra and Brahma who were adopted by the early Buddhists of India from the Hindu pantheon. In Japan these two guardians are called Ni Ten O. They stand on either side of the gates of Japanese Temples. In T’ang times the Dvârapâlas became confused with two of the Guardians of the Four Quarters of the Universe and where attributes are lacking it is impossible to tell whether the figures are Dvârapâlas or two of the Lokapalas. The fact that the Lokapalas were kings over various classes of demons would lead one to consider our two grave figures as belonging to that group since they are shown tramping demons under foot. These can be compared with two stone statuettes of guardians in the Museum collection in which case the bases represent rocks only.