The objects dealt with in this article form part of the exhibition lately arranged in the southeast room on the ground floor of the Museum and intended to illustrate the representative and decorative art of some primitive peoples of Africa and Oceania. As examples of this art, remote in its results, as it probably is in conscious purpose, from realism, yet born of and still unmistakably affected by an interest in reality, the productions of Maori craftsmen are preeminent.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-40

Image Number: 2402

The Maori inhabit the southernmost land reached in their oceanic wanderings by the remarkable race which colonized the scattered archipelagoes of the Pacific from Samoa to Easter Island and from the Hawaiian Islands to New Zealand. In the British Dominion last named the Maori have prospered better than Polynesians elsewhere in contact with the whites, whose settlement in their land these first New Zealanders formerly contested with great courage and determination. This group of the Polynesians had maintained themselves for centuries in an environment where nature is less generous in providing for men’s needs without energetic collaboration on their part than she is in the tropical regions of the South Seas. They had to employ, in their efforts to win from her their livelihood, means more arduous and unremitting than those which a less exigent necessity imposed upon the kinsfolk they had left in the tropics. They have thus preserved the vigorous mental frame and the virility of disposition which were the inheritance of the adventurous seafaring stock from which they came.

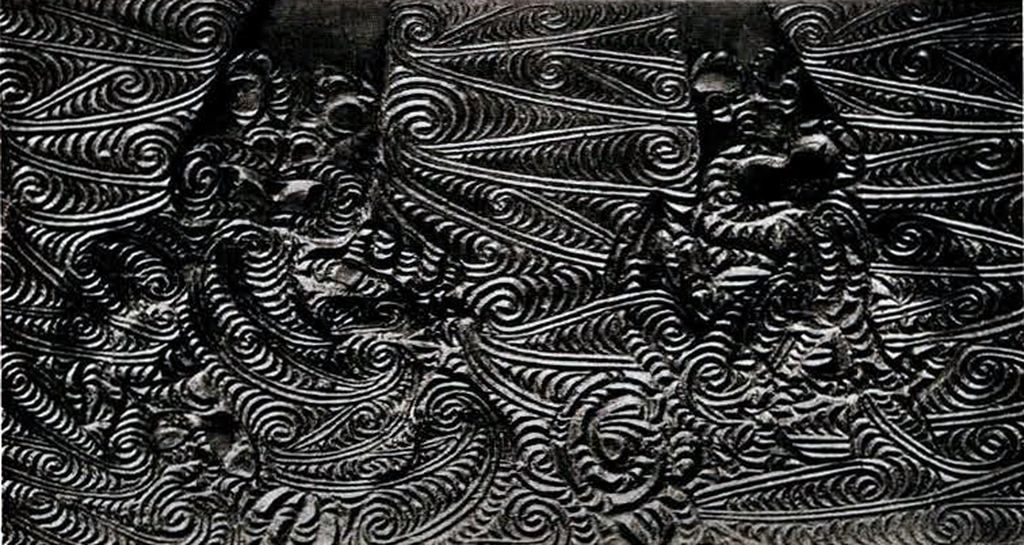

Something of this energy and of the liveliness of imagination which is allied to a practical resourcefulness in meeting the workaday situations of life is reflected in their extremely vigorous and fanciful carvings, executed in a style so peculiarly their own that no one who has known two or three examples would be likely to fail in recognizing the Maori manner wherever seen.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-40

Image Number: 147

Museum Object Number: 29-93-40

Image Number: 148

A detail of design or an individual figure is seldom so accentuated as to overshadow the general impression of richness, often combined with an almost lacelike delicacy, that is received from the whole. Using as he did the most primitive and inexact of tools, the artist seldom fails in symmetry. Though his lines and curves interlace in a maze of arabesques. or vary with the limitations of his material, they are seldom faulty or misplaced. And if tradition, its authority reënforced by the terrors of the taboo and the awe of the gods of the forefathers, prescribed the general form and manner of his work, his imagination found means of varying details and arrangement so that it is rare to find two quite identical examples of any one design.

Religious tradition is both guide and ally of the arts among peoples whose social and religious ways of life are summed up in a phase of culture which we are accustomed to characterize as barbarous or savage or low. Of the three means by which the artistic genius of the Maori found its principal expression—tattooing and the carving of canoe decorations and of house ornaments—two were directly in the hands of a division of the priestly caste, and the third was subject to its censorship or control. For though the tattooer was not, as such, a priest craftsman, his subject and himself were, during all the time of the operation, under a taboo; and a tattooer of any eminence did become, when his skill was generally recognized, a member of the priestly caste, a tohunga.

The case of the tattooer, indeed, provides an enlightening commentary on the influence of such sacerdotal control on art—if one should be disposed to claim that its results were mainly productive of evil. The tattooer, it has been said, was not necessarily a tohunga, and therefore not to quite the same extent as other artificers subject to that influence; and while some of the finest examples of Maori decorative art were in his medium, so also were some of the worst. This is part of a song of the tattooer as he plied his chisel.

The man who will pay well

With beautiful tattooing;

But the man who will not pay

Crooked and wide will be his marking.

A short account of the ceremonial observances which were connected with tattooing will serve to illustrate the intimate connection of religion with the daily life and the art of the Maori. Perhaps it will be as well to say that the word taboo (tapu) is here used in its most generally accepted sense, as meaning a ritual prohibition the violation of which involves dangerous or fatal consequences from the wrath of the gods.

“When the skilled artificer (tohunga) was doing his work of tattooing, he, the person operated on, and all the people of the village were tapu, on account of the blood on the operator’s hand. At the conclusion of the affair, three ovens were lighted, one for the artificer, one for the gods, one for the person just tattooed and for the rest of the people. To raise the tapu, the tohunga first washed his hands, and then taking a hot stone from the gods’ oven would throw it from one hand to the other, then replace it in the oven. This transferred the tapu to that stone, and the food cooked conveyed it back to the gods. The food in the gods’ oven when cooked was put into a basket and hung up in a sacred place.” [E. Tregear, The Maori Race, pp. 265, 266.]

Museum Object Number: P3107B

Image Number: 154

The taboo which prohibited ordinary intercourse with the persons involved being thus removed, they were now once more noa, common, ordinary, restored to their normal position in the social and religious scheme of things. An earlier writer on Maori customs, in speaking of a village where a number of chiefs were undergoing the operation of moko or incised tattooing, says that “it appeared as though some dreadful disease had suddenly struck the greater part of the inhabitants and deprived them of the use of their limbs” for being all “under the law, they could not feed themselves with their hands.” A wooden funnel was used for feeding men who were being tattooed.

Men were tattooed both on the face and on the body; women not often and only sparsely on the body, and, on the face, usually only about the mouth and chin. “When the daughter of an important chief had her lips and chin tattooed, a day was set apart on which the tribe would assemble to view the work of the artist. A party would be sent forth some time before to secure a member of another tribe for sacrifice and to give strength to the tribe by eating’ .” [Elsdon Best, Trans. N. Z. Inst., xxx, 1897, p. 38.]

Since the most solemn sanctions and observances of religion surrounded the artist, and to a great extent conditioned the quality of his work—as we may infer from the above statement of the importance attached to its public exhibition—it is clear that religion and religious feeling, while they imposed great limitations on the artist, must at the same time have inspired him to do his best within the limits imposed. And the public esteem of works of art was an important additional spur. With regard to the wood carvings we are told on the one hand that “departure from the lines laid down by their ancestors was considered an aitua or evil omen to the carver, which often resulted in death;” and on the other that fine examples were regarded by their owners and by the people in general with as much affection and admiration as are accorded to great pictures or sculpture by connoisseurs and amateurs of art among us. While the artist’s originality was thus curbed by tradition strengthened by supernatural sanctions, technical proficiency and, within narrow limits, a certain freedom of fancy, were encouraged by the same tradition and by a public sentiment closely allied with it.

Museum Object Number: 18128

Image Number: 123

The word tattooing has been used above to denote the operation we are considering, although the typical Maori performance was not tattooing proper. The word tattoo (tattaow, tatu) was introduced to Europeans in the latter part of the eighteenth century by Captain Cook and his companion, Lieutenant Banks, and properly refers to the Tahitian process, paralleled among lightskinned peoples in various parts of the world, of perforating the cuticle with a series of small holes and inserting a pigment, the result being that, on healing, the skin showed a pattern formed by an almost continuous line of small blue spots. This method was also followed in New Zealand, principally for body tattoo; but the characteristic Maori process was known as moko, and consisted in making a series of continuous small rectilinear cuts in the skin by tapping with a light mallet upon the head of a miniature adze with a chisellike bone blade, the colouring matter being immediately applied to the bleeding wound thus caused. When the wounds healed the pattern appeared in series or groups of bluecoloured grooves in the skin, deep enough sometimes to lay a pin in. Moko was thus, to all intents and purposes, a kind of skincarving.

Museum Object Number: P3223

Considering the yielding nature of his material, especially where, as on the cheeks, there were no bones near the surface, the accuracy and clearness with which the designs were executed are quite remarkable. The artist was conscious of the importance of his calling, and knew besides that he was executing a memorial to his own skill that would endure beyond his span of life. “The privileges of moko [were] limited to men of distinguished birth or to warriors celebrated for their grand deeds.” “To have fine tattooed faces was the great ambition of young men, both to render themselves attractive to the ladies and conspicuous in war; for, even if killed by the enemy, whilst the heads of the untattooed were treated with great indignity, and kicked on one side, those which were conspicuous by their beautiful moko were carefully cut off and . . . preserved.” [H.C. Robley, Moko or Maori Tattooing, pp. 26, 271 The heads of relatives were preserved with even greater care.

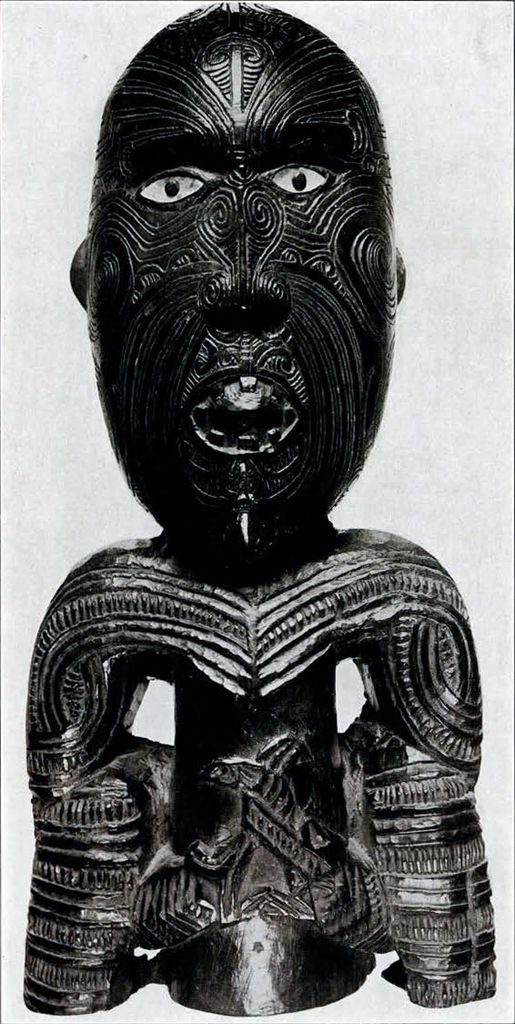

Whether the woodcarving or moko was the earlier development, is, of course, an open question, but there would seem to be little room for doubt that the woodcarvings that have survived owe some of their most important features to the moko. Apart from the purposes just indicated as those for which the face moko was assumed, it was intended to render the appearance of a warrior more terrible to an enemy. The grim impressiveness of some of the house carvings is largely due to the conventional manner of representing the faces of the human figures which are their most important feature. The faces of warriors as they advanced to battle with widely distended mouths, protruding tongue, and eyes glaring wide under brows strained upwards, furnished the model for these highly idealized carved countenances. And the moko must in the first place have been intended to accentuate and to mark on the living face when at rest these traits of the warrior’s expression at the moment when he attained the ideal of impressiveness.

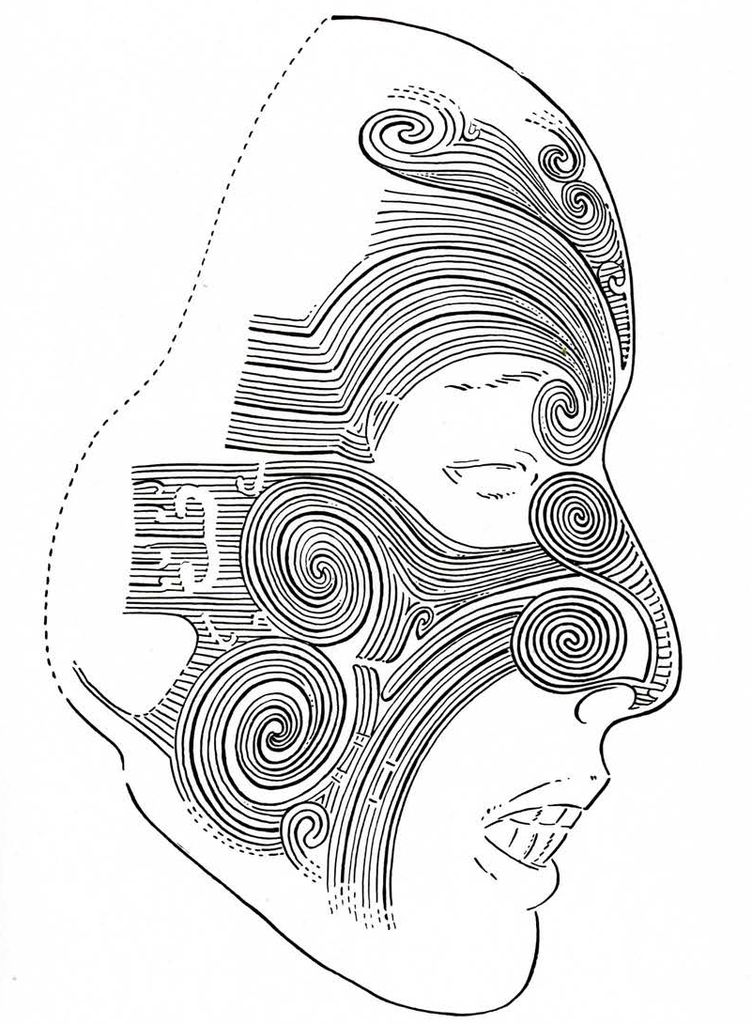

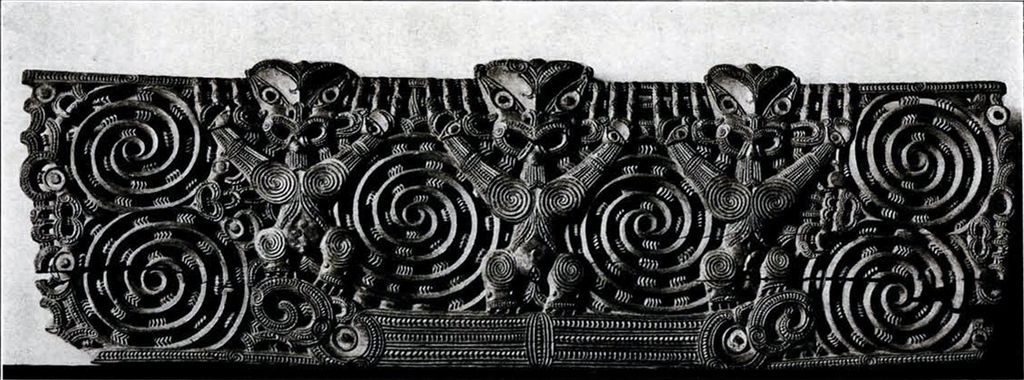

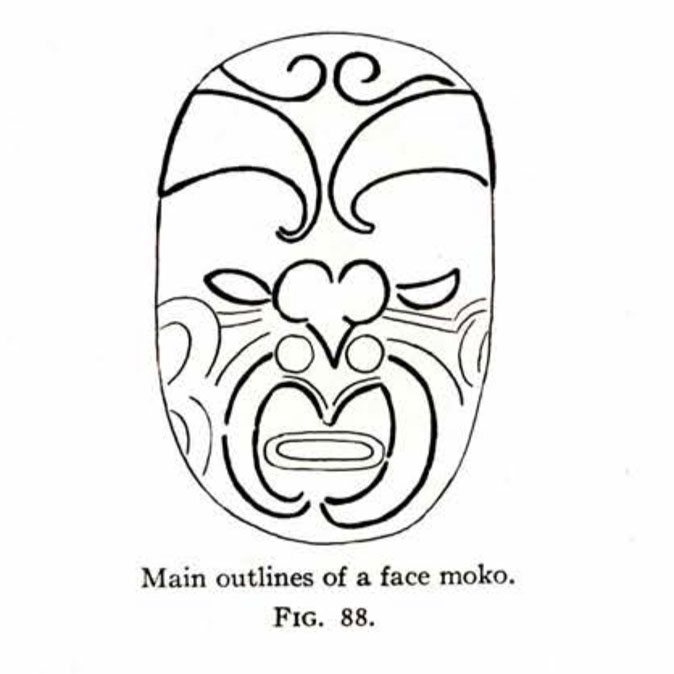

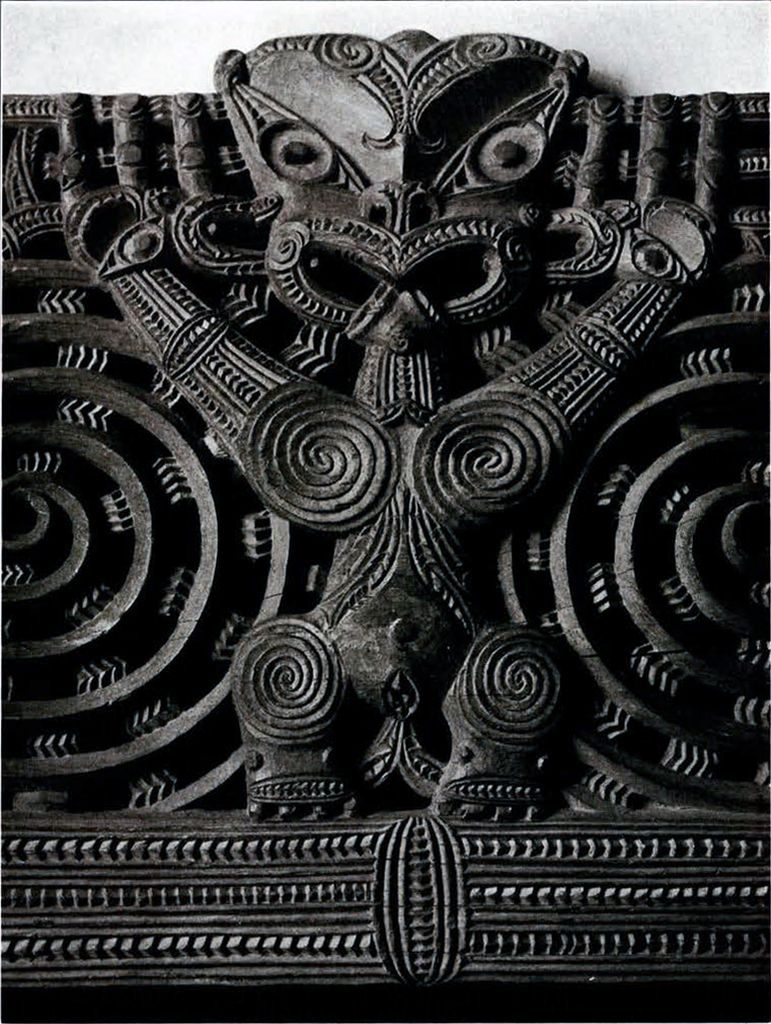

If the face of the lefthand figure (Fig. 86) from the door lintel (Fig. 87) be compared with a drawing (Fig. 88) of the principal outlines (such as the moko artist might have drawn in blocking out his design on the skin) of a carving intended to represent realistically a mokoed head, and, further, with those of a sketch of his own face moko (Fig. 89) made by a chief as his signature to a land grant, it is evident that the conventional human face of the wood carvings bears a very close relation, probably that of derivation, to the moko face markings.

In the former the head has become merely a vehicle for a highly stylized treatment of the regions of the mouth and eyes, the all-important instruments of facial expression. It scarcely needs more than a casual comparison of the illustrations referred to, to make the connection evident. Only two points, perhaps, need to be particularized. These are the shortening of the nose, which feature, in some carvings, almost disappears, and the emphasis placed on the tubercle of the upper lip, which descends in a sharp point to the protruded tongue. In nature, even in a case where the tubercle is especially marked, the peak it makes in the normal outline of the lips would tend to disappear from a mouth so widely distended as it is represented to be in the carvings.

Museum Object Number: P3109

Image Number: 121

The two points are in fact closely related. The distinctive nose moko with its two spirals on each side lays greater emphasis on the upper of the two, which is usually the larger. The tip of the nose itself invades the space marked off by the inner outline of the moko of the mouth region. It is these main outlines of the face moko which give the woodcarver the features of his ideal face. So the tip of the nose becomes included in the conception of the terror-striking distended mouth, and the upper nose spirals give the suggestion for the beastlike shortened snub nose, while the lower spirals of the nostrils, inconspicuous in a full face view, tend to disappear (cf. Figs. 89, 91).

It is worth noting in this connection that one of the mokoed heads in the exhibition shows a feature said to be a mark of those heads which were preserved in memory of relatives. In the process of mummifying, the lips were sewed together, a stitch connecting the tubercle of the upper lip with the middle of the lower. In the mummied heads this gives the mouth the appearance referred to, and may have contributed by suggestion to the final result.

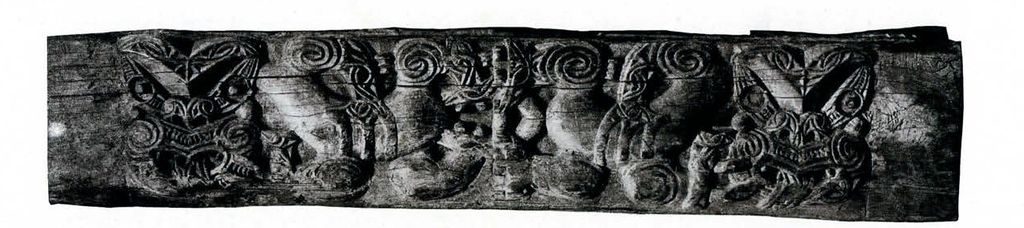

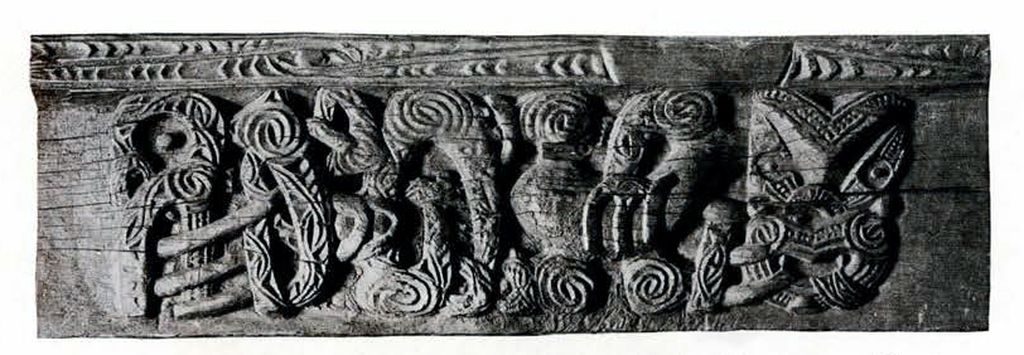

Figure 87 is a good example of several of the principal elements in Maori designs—the spiral, the scroll, the chevron, and a detail which has been called the ladder. consisting of parallel vertical or horizontal (in this case, horizontal) lines connected by short bars, which sometimes assume the chevron form. The skilful adaptation of forms to available space which is so characteristic of the carvings is well illustrated in the filling in of the triangular or roughly diamond shaped spaces between the large double spirals and the outer edges of the decoration on the one hand and the human grotesques on the other with adaptations of the form of the faces of the three principal figures.

The carving appears to represent an old Maori legend of the temptation of man by a manaia or mythical monster with the head of a bird. The arms of the figures are upraised and terminate in the usual three (elsewhere sometimes four) fingered hand. Across the base of each hand stretches the head of the manaia, which seems to be whispering to the victims. The head of the manaia appears again at each end of the horizontal panel which supports the three upright figures, this time with the curving beak, the point of which is lost in the case of the other heads, further stylized into a whorl or scroll. The eye spaces were originally filled, according to the convention, with discs of haliotis shell pierced to allow the pupil or iris, in the shape of a small peg or boss carved in the middle of the eye opening, to appear.

Museum Object Number: P3111A

Image Number: 151

Museum Object Number: P3111B

Image Number: 150

Museum Object Number: P3111A

Image Number: 152

The house was a low walled structure with a high gable roof. Commonly there was a single door flanked on one side by a window, both opening on to a porch which occupied the width of the front end of the house. The houses of persons of importance and the storehouses were adorned with carvings, both within and without. Doorways and windows had elaborately carved jambs and lintels. The sloping edges of the gable were faced with carved boards. The spaces between the uprights used in constructing the walls were filled in with matting. The point of the gable was crowned with a grotesquely carved human figure. Slabs with the typical human grotesques were sometimes hung like pictures on the matting in the house, or were used to close the small opening of the door of the storehouse. Great upright redpainted carved slabs sometimes flanked the low outer sides of the porch. All these were regarded as important works of art, greatly treasured by the owners, and admired by the people in general.

As recently as the late seventies of the last century, the old customs and ceremonies connected with the building of houses were kept up. An interesting account is extant of the building of the house of a member of a family of chiefs about that time, as related by his widow. Five chiefs, one of them the widow’s brother, with about seventy tribesmen, convoyed the posts for the building a long distance, at a cost for freight and passage of over eight hundred dollars. The first post erected was named after a chief. To assist in the raising of the ridge pole, which was named after another chief, a tohunga was sent for, who chanted an incantation, “The Raising of Tainui.” The widow’s brother was one of the woodcarvers. Some of the workmen having burned some chips from his chisel in a cooking fire, “a sickness fell upon our people,” so that a special ceremony had to be performed to stay the plague. When the building was completed another tohunga was sent for to conduct the ceremonies necessary for the removing of the taboos which affected a house under construction and its builders. Then men entered and ate food in the house. Finally the widow and two other women stepped ceremonially across the threshold into the building, as the morning star appeared in the sky. This removed the last taboo, that which prevented women from entering a house of such importance.

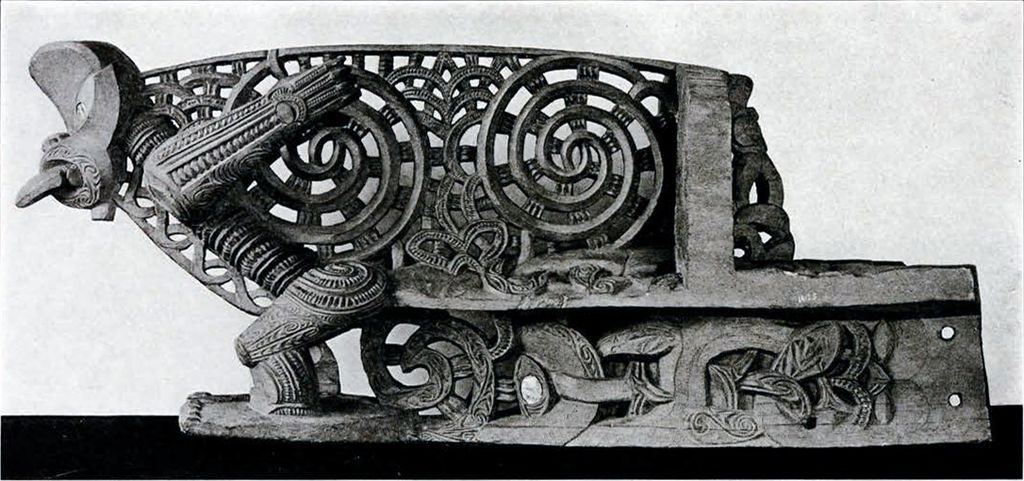

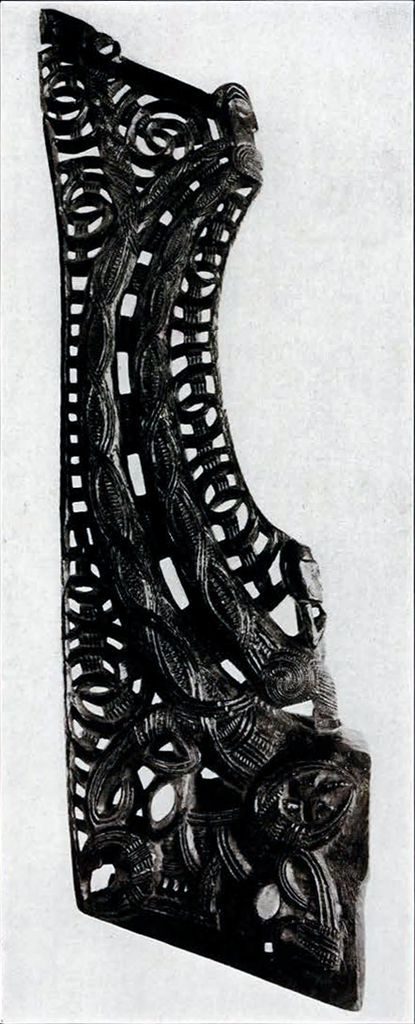

House rafters and the topsides and prows of canoes were painted in elaborate and harmoniously arranged designs in black, red, and white. The making and the launching of war canoes were accompanied by incantations and ceremonies even more numerous and elaborate than those which attended the building of houses. The examples of figureheads and stern pieces illustrated here and to be seen in the exhibition, show the style of canoe ornament on which so much care and skill were lavished. The airy winglike appearance of the stern ornament, the lines of the detachable prow, reaching forward to the eager straining figure at its point, so well suggestive with its attitude of one about to leap or dive or fly, of the swift motion of the long canoe it seems to lead or convoy—all is another example of the high congruity of Maori decoration with the objects to which it is applied.

Museum Object Numbers, From Top: 29-93-14B, 29-93-14A

Image Number: 156

Museum Object Numbers, From Left: 29-93-15B, 29-93-15A

Image Number: 157

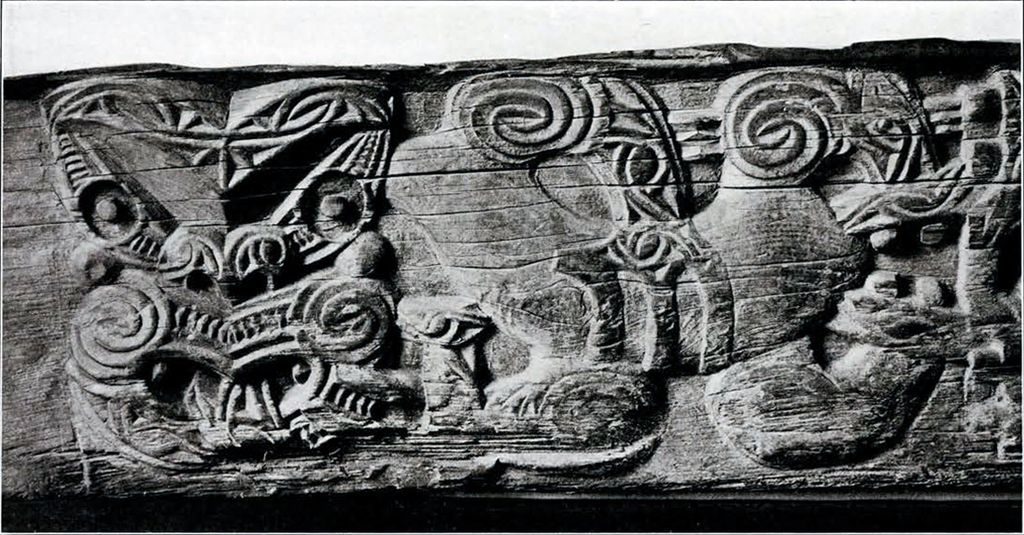

The birdheaded figure at the bow is a taniwha, a monster of the deep, and its close association with the spiral ornament of the central portion of the figurehead suggests a connection with the manaia of the house ornament described above. There are several elements of construction and design common to both kinds of canoe ornaments (Figs. 92 and 93) from the east coast of North Island. In the prow ornament the upper longitudinal central piece, which terminates forward in the winged figure and to the rear in a transverse slab carrying a small figure looking into the boat, was formerly carved from a separate board, and was named manaia, a name which it retained when carved, as in the specimens shown here, from the same solid log as the rest of the figurehead—the triangular base and the transverse slab. The manaia comprises two spirals and a composite figure between them, which in its origin is made up of two embracing taniwhas in profile facing each other. In Figure 92 this detail has degenerated into an apparently meaningless group of curves. Beneath these, on the top of the triangular base slab lies supine a figure of Maui, the demigod who fished up the North Island of New Zealand from the depths of the sea with his fishhook. Below this again are three human or semihuman figures disposed horizontally. In neither of the figureheads here illustrated has the carving been completed—it was a lengthy process, and sometimes extended over a period of years—but in Figure 94, at the right, may be noted a peculiar feature of the woodcarvings which appears again in the house ornaments, Figures 95 and 96. In some of the figures, the face is set with its long axis vertical, while that of the body is at right angles to it. This occurs in oblong carvings which are to be placed with their long dimension horizontal, and the convention is no doubt due to the wish to keep the head in its normal position with regard to the beholder so as to be readily recognizable.

Practically the same details of design may be traced in the stern piece (Fig. 93), in variant forms and a different disposition.

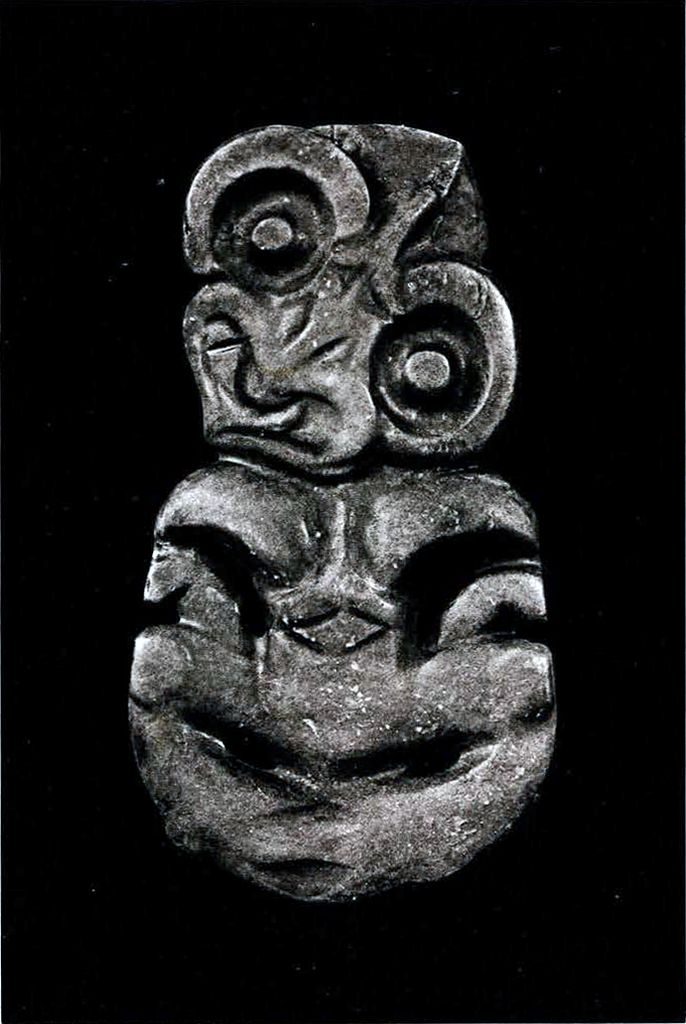

Museum Object Numbers: P3112.3 / P3112.4

Image Number: 155

Museum Object Number: 29-93-14A

Image Number: 158

Various suggestions have been offered for an explanation of the origin of the Maori spiral. Of these perhaps the most promising is that which would make it a serpent form and associate it directly with the manaia. Though there are no snakes in New Zealand, the Maori tribal memory is long and preserves other elements of an environment antedating that in which written history knows this people. The spiral, as we have seen, forms an important feature of the face moko. In the body tattoo, it appears on the buttocks, and when transferred to the full face carvings of the human figure, is shifted forward so as to cover the hip and groin. With this treatment of it may be compared its placing on the upper part of the trunk in such carvings to represent the breasts, though it takes in the shoulders as well. A different result of the convention, by which elements of a side view of the body are brought into a view en face, is shown in the human figures carved on the slabs, Figures 95 and 96, in which the trunk in contrast to the limbs and head is shown in profile. Such devices as this are undoubtedly connected with the elaborate symbolism whose meaning is still largely concealed behind these figures, distorted and grotesque enough regarded merely as representations of the human form, yet which fill so well their place in a decorative system or scheme that possesses a unique and peculiar beauty.

Not only the products and the processes but the materials and tools of the crafts were regarded as sacred, endowed with or protected by divine might. The trees which furnished the planks for their carvings and the other materials for house and canoe building were especially objects of reverence if not of worship. Famous trees bore special names and had special supernatural qualities. Some were set apart for generations for the building of a great war canoe.

The legend of the Coming of the Taki-timu, one of the fleet of canoes which is believed to have brought the Polynesian ancestors of the Maori to New Zealand from Tahiti in the fourteenth century of our era, contains an interesting picture of the conditions under which the great war canoes were constructed.

The Taki-timu was built from a great tree standing beside a stream. The tree had been consecrated to this purpose by an ancestor of the builders. It was felled by undermining it at the root, and sheds for the workmen and storehouses for their food were built beside the prostrate trunk. Experts were sent for to direct the work, and the stone axes of these great tohunga were specially named. Before the work was begun, incantations were pronounced over the axes, the tree, and the workmen.

. . . give to these thy sons

That they may possess the ancient and occult powers,

Like thy god-like sons . .

Now I uplift my famous axes .

Axes with great edges, sharp axes . . .

They enter within the wood . . .

What is the name of my canoe? It is Te-pu-whenua! . . .

Like a canoe of the dark ages is my canoe!

Like those used by the gods . . .

A canoe to direct its course to the new land is my canoe! . . .

Brave to breast the waves of ocean is my canoe!

To reach the land, to the mainland, direct her course!

When the trunk had been shaped, a ditch was dug and the hull buried in it, to season the wood. In the meanwhile, the separate parts, the fore and the after end pieces, the topsides, the figurehead, the mast which was to carry the triangular matting sail, and the yards, were dubbed out, and then also seasoned in the same manner as the hull. When the canoe was finished, it was dragged with the help of skids to the place on the shore from which it was to be launched. There the finishing touches were put to it; the hull and the strakes were daubed with resin and painted red with hæmatite.

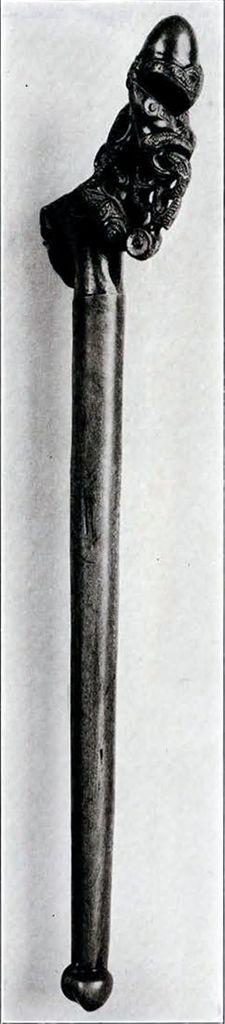

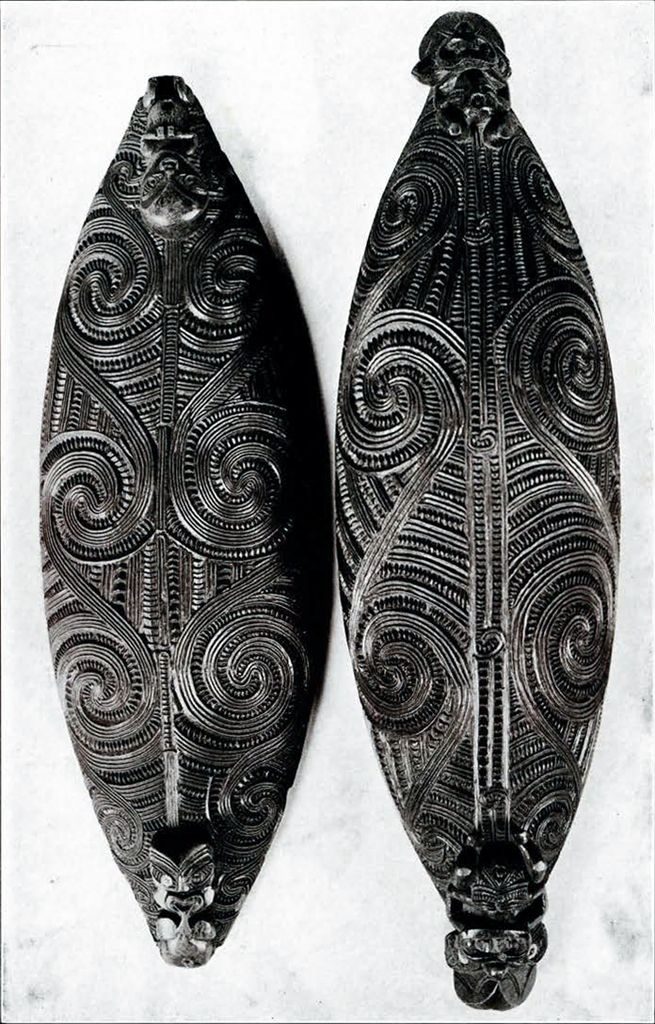

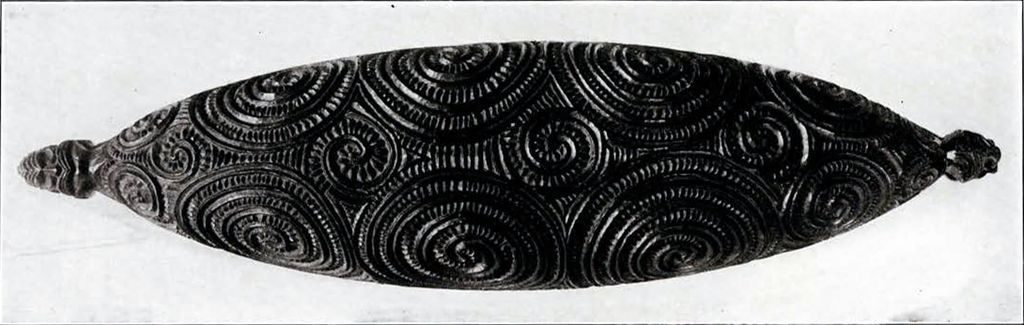

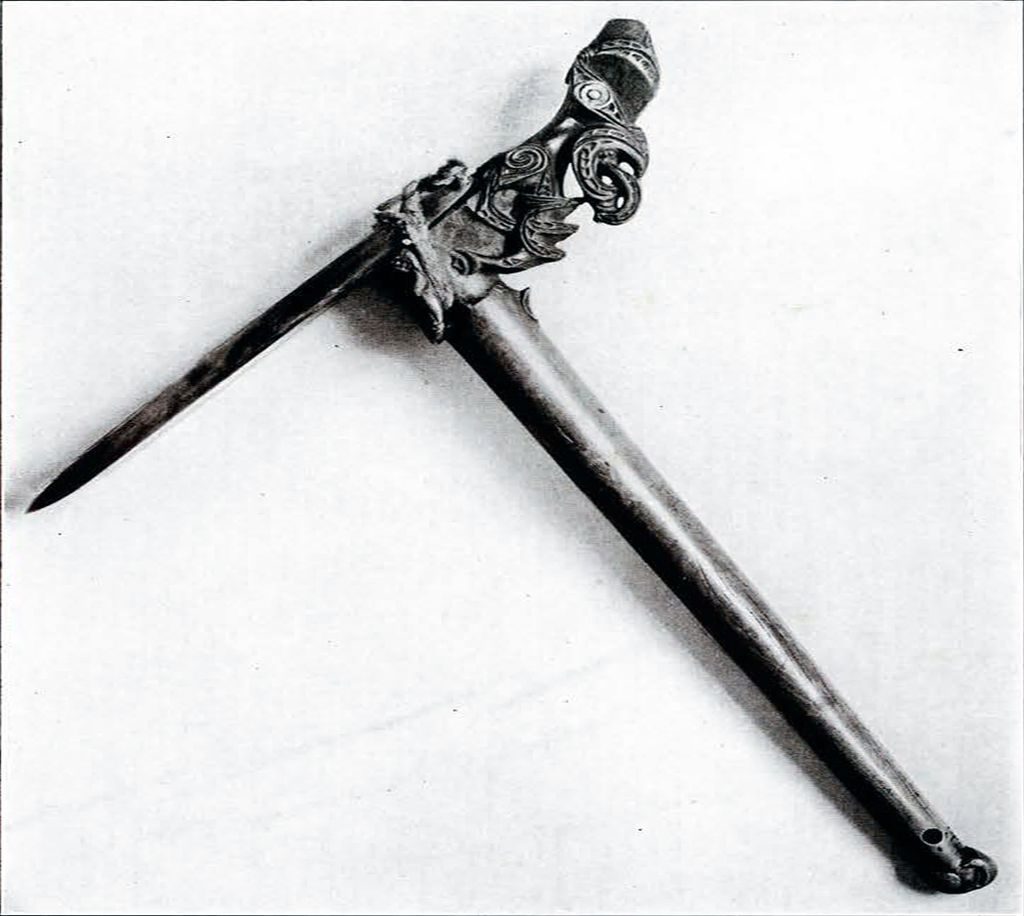

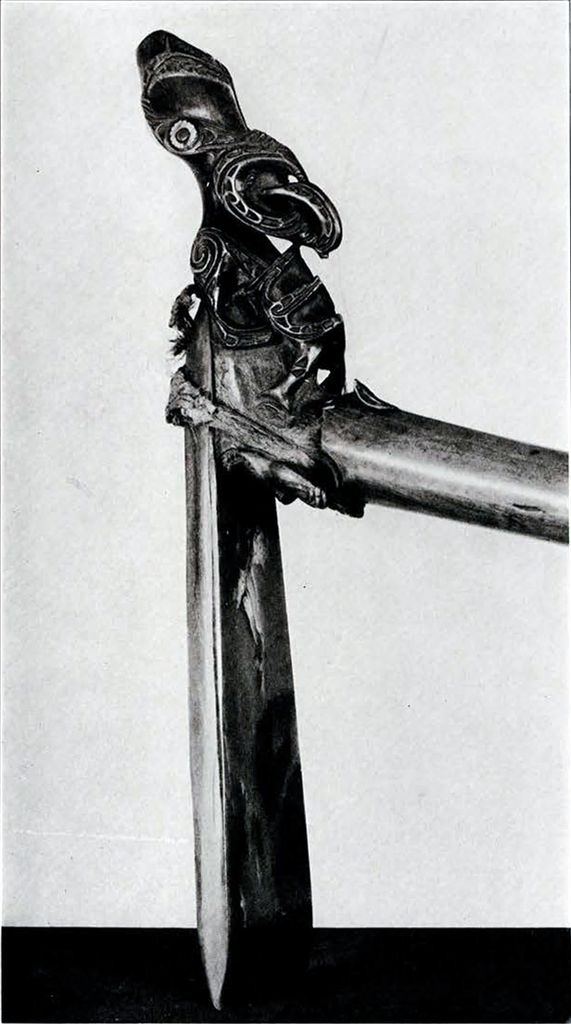

Of the other examples of Maori carving in the exhibition the most interesting are the feather boxes (Figs. 98, 99 and 100), the war adzes (Figs. 102 and 103) and the greenstone pendants in the form of a human fœtus (Fig. 105.) The boxes were used for the safekeeping of the feathers worn as hair ornaments. They show interesting forms of the human figure (carved as handles for the boxes), the scroll, the ladder, the spiral, and combinations of these, which are the principal elements of design in the other carvings.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-13

Image Number: 174

Figure 102 is a particularly fine example of a war adze, with the graceful form and perfect proportion and balance of its parts. A learned and sympathetic student of the life and art of the Maori, in speaking of the excellent taste which their craftsmen exhibited in their work, and the true artistic instinct they displayed, the patient labour of love bestowed on the beautifying of even the homeliest articles of everyday use, recently said : “The Maori never allowed the decorative to encroach upon or mar the useful. Ornamental carving was confined to such parts of implements as to preclude any interference with effective handling. When you see a canoe paddle carved all over, rest assured that it was not used for paddling purposes. When a hafted stone adze, carrying carved designs on the hand grip is offered you, reject it with bitter words. It is a fraud. . . . . The Neolithic Maori combined the useful and the ornamental whenever it was possible to do so. . . . [He] was more than an artisan, he was an artist. He loved to adorn the commonest artifact fashioned by his hands, and to express in every fabric his keen appreciation of true and faithful work.” [The Relation of Decorative Art to Utility in Maori Artifacts, an Address to the Wellington, N. Z., Academy of Fine Arts, by Elsdon Best, October 12th, 1918.]

With the primitive means at his command, the beautiful lines and perfect finish of the hard greenstone alone in the weapon here shown required a degree of skill and painstaking workmanship which seem almost incredible. And the oldest and the finest productions of these artists were accomplished before the white man brought them iron and steel to replace the bone and shell and stone of the tools of their own devising. Is it no more than a coincidence that the improvement of tools and the discovery of easier methods of dealing with refractory materials goes hand in hand with a decline in the quality of workmanship and a weakening of the devotion of the workman to the task whose very difficulties were a spur?

H.U.H.

Museum Object Number: 29-93-13

Image Number: 175

Museum Object Number: P3124

Image Number: 137

Museum Object Number: 29-93-41

Image Number: 134

Museum Object Number: 29-93-41

Image Number: 133

Museum Object Number: P2241

Museum Object Number: P3110

Image Number: 146