THE eighth season of the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania started at Ur on November 1, 1929, and ended on March 19, 1930. The staff consisted of my wife, who as usual was responsible for the type-drawings of objects, the planning of the cemetery, and for a share in the field-work; Mr. M. E. L. Mallowan, general archaeological assistant; the Rev. E. Burrows, S.J., epigraphist; and Mr. A. S. Whitburn, architect. Hamoudi was, as always, head foreman with his sons, Yahia, Ibrahim, and Alawi acting under him; owing to the fact that work was always going on in at least two spots fairly far apart, greater responsibility than usual was thrown on the younger foremen, who answered admirably to the demands on them; Yahia combined this work with that of staff photographer. The number of men employed varied slightly at different times, but was always over two hundred and for most of the season kept at about two hundred and forty, a number well in excess of the average of past seasons; the amount of work done was correspondingly great. I have to thank the Royal Air Force in Iraq for help of many sorts and not least for an air photograph mosaic of the site taken at the close of the season and of much value for purposes of comparison with earlier photographs; Lt.-Colonel Tainsh, Director of the Iraq Railways, for facilities enabling me to undertake a short experimental dig at Meraijib, a prehistoric site some ten miles south of Ur; and the Director of Antiquities, Iraq, for his help in this Meraijib work and to the Expedition in general. I must also acknowledge my indebtedness to the staff of the British Museum Laboratory, where the work of restoring and cleaning was as usual carried out., and in particular to Mr. E. C. Padgham for his success with the silver objects; Mr. Evan Watkin of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities undertook the mending of the stone vases, and for the mending of the pottery the services of Mrs. F. W. Bard were secured.

Image Number: 191611

Three distinct tasks were envisaged by our programme for the winter, all of which were successfully carried out: (a) The continuation of the excavation of the royal cemetery resulted in the completion of the work; the limits of the graveyard were found, and though a certain number of graves, principally of the late period, undoubtedly remain, they would not repay the cost of excavation. The clearing of the cemetery led to deeper digging, and in two places virgin soil was encountered; between this and the bottom level of the royal graveyard were found graves of a totally different character and date illustrating a period of history hitherto scarcely represented at Ur. (b) The further investigation of the Flood stratum occupied a large gang of men for the greater part of the season, and here again work was carried down to virgin soil. (c) The tracing of the walls of the city was completed. This involved the excavation of three temple sites and of a number of houses in addition to the work on the wall itself.

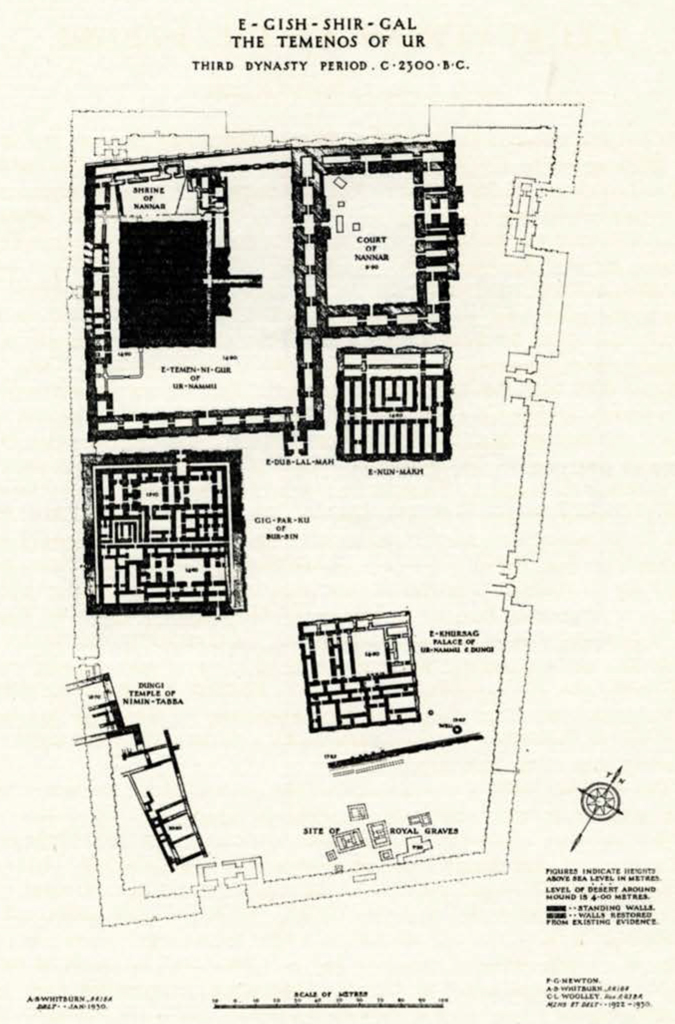

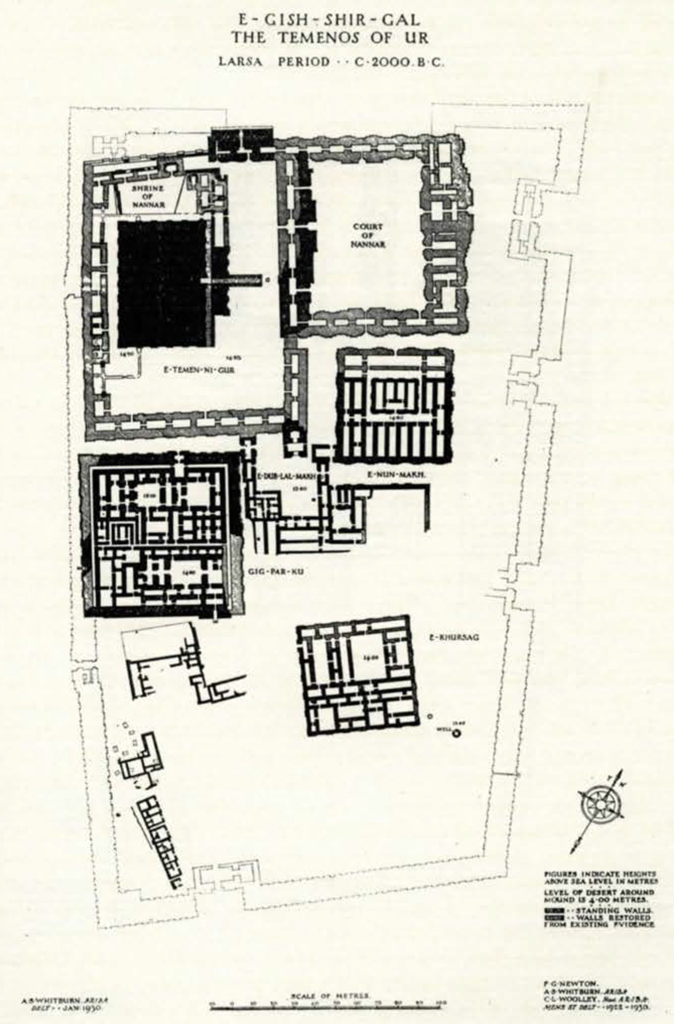

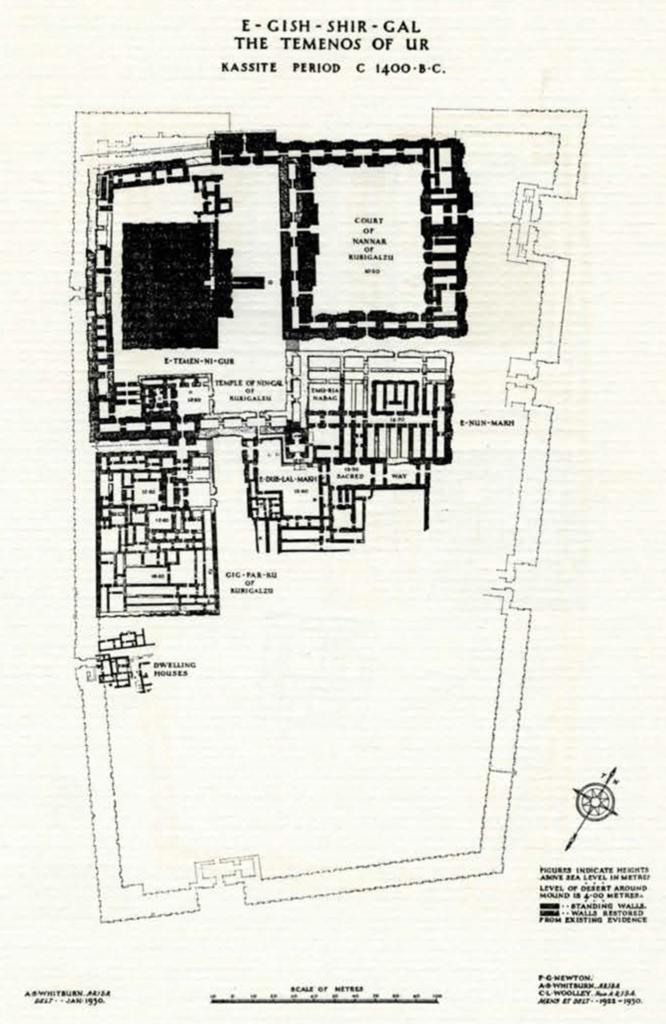

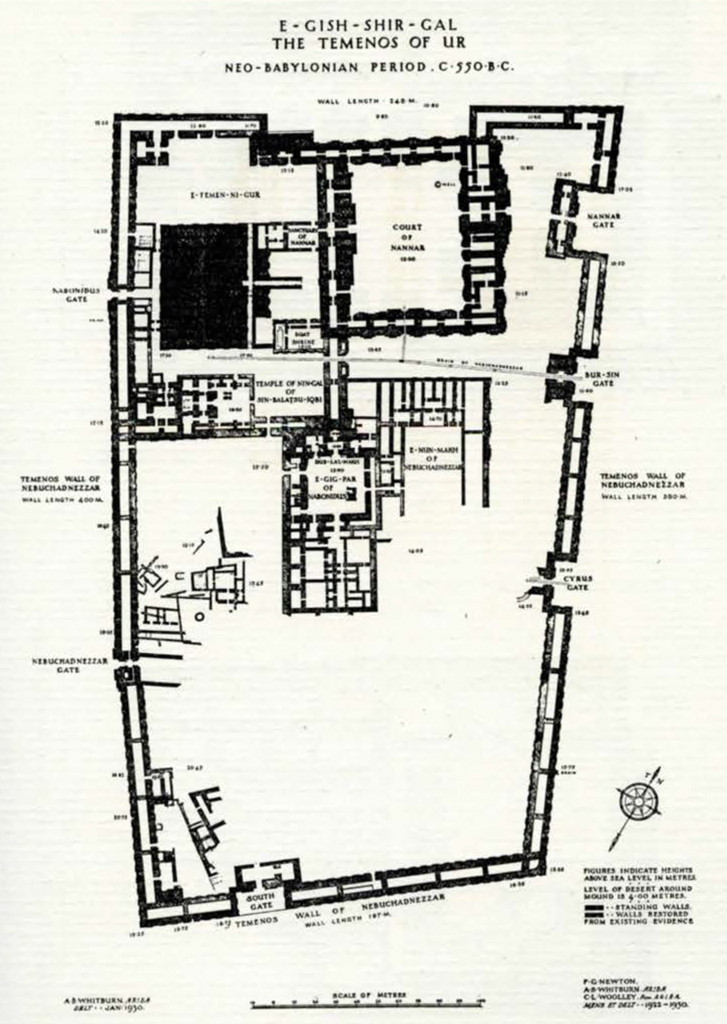

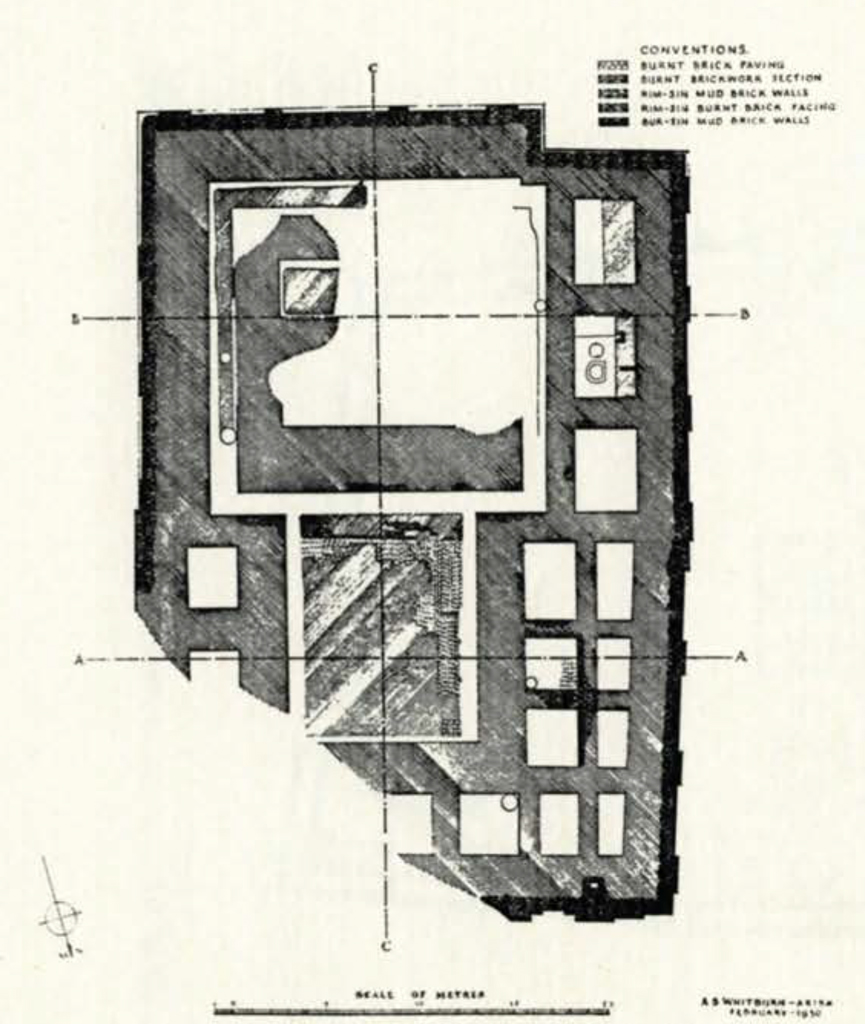

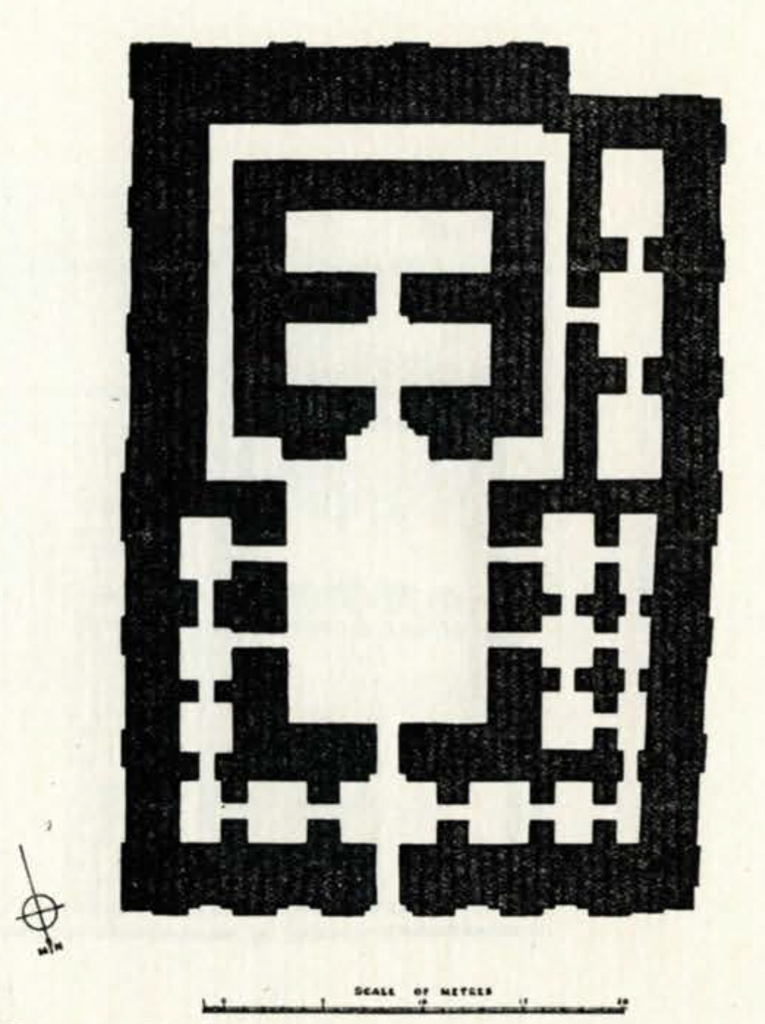

Advantage was taken of Mr. Whitburn’s presence to work out on the spot the ground-plans of the Temenos of Ur at different periods. The material for these plans had, of course, been amassed during the past seven years, but to sort and combine that material a certain amount of fresh survey work was required and doubtful points bad to be re-examined. The Third Dynasty plan [Plate I] has yet to be completed by the excavation of an important building of Bur-Sin found this season on the outskirts of the cemetery area; that of the Larsa period [Plate II] is probably final, and those of the Kassite and Neo-Babylonian periods [Plates III and IV] include everything that now remains of the buildings of those dates. The series is of the greatest interest as showing the modifications and rebuilt-lingo of the principal temples between 2300 and 530 B.C.

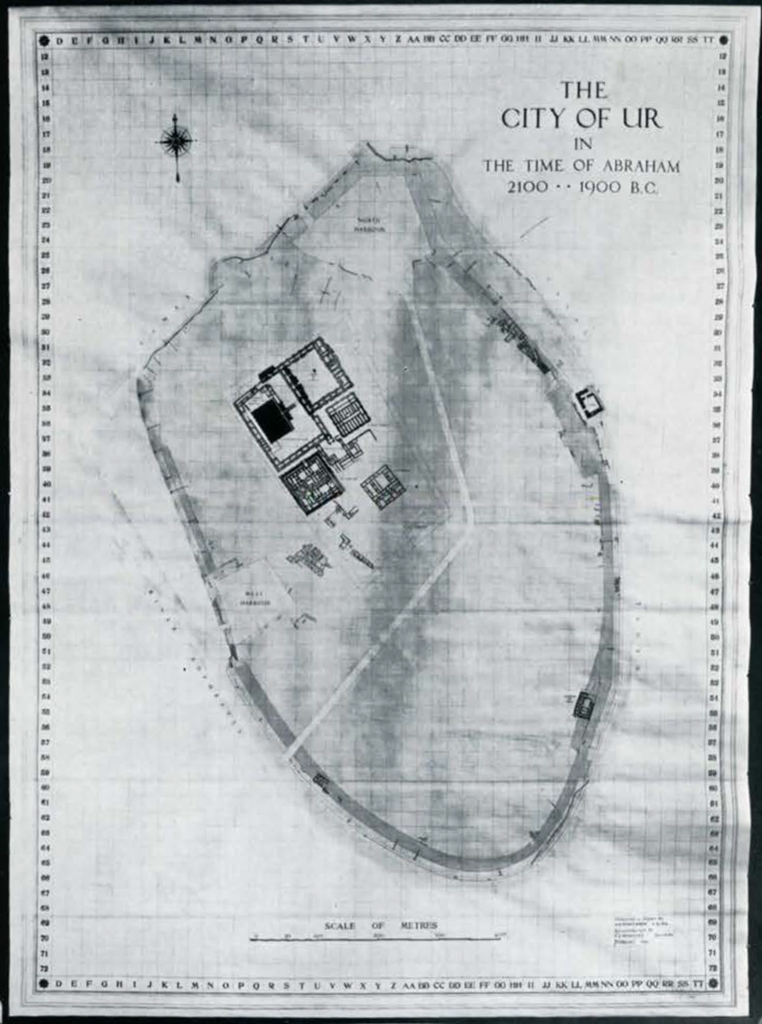

The Work on the City Walls [Plate V]

The general character of the defences had been ascertained by partial digging carried out in the season 1928-29.1 The principal new discovery of this year was that the ramparts which form the base of the wall proper served also as the revetment of a canal or river bank. Along the west side of the city ran the Euphrates; canals along the other sides virtually transformed the site into an island; another canal ran through the heart of the city.

Image Number: 191612

The rampart of mud brick, to judge by the measurements and character of the bricks in it, dated from the Third Dynasty of Ur and was probably the work of Ur-Engur (Ur-Nammu); this is confirmed by the fact that a building of Bur-Sin his grandson stands actually on the rampart, which must have been already standing. It was, in places, re-faced several times at later dates, but seems to have been little altered up to the Kassite period, and even in Neo-Babylonian times its general line remained much the same. The rampart appears to have been about eight metres high and varied in width (at its base) from twenty-five to thirty-four metres; its front face sloped at an angle of about fifty degrees, forming the canal or river bank, its back face rose only some metre and a half above the terrace on which the town stood; to this terrace the rampart served as a retaining-wall. Of the wall of burnt brick which Ur-Engur built along the top of the rampart (as is known from inscribed bricks found re-used at various points inside the town), not a vestige remained anywhere. What did survive were public or private buildings, mostly of the Larsa period, which were aligned along the top of the rampart, their outer walls joined up so as to make a continuous line of defence. For the most part these buildings, to judge by their scanty remains, were set well back, leaving a broad flat promenade between the wall line and the edge of the sloped revetment, which would be an excellent manœuvring-ground for defending troops. At intervals, though with no regularity of system, the buildings projected forward, forming salients almost flush with the top of the slope, and in one case at least stepped well down it; where this occurred the lower part of the building was filled in solid with earth as if for the foundations of a tower.

Image Number: 191614

A high line of mud-brick construction with water or low ground all along one side of it was bound to suffer severely from weather, and most of the rampart has been denuded into a shapeless mound whose present face slopes gently and irregularly back from the canal edge to the extreme back of the brickwork; its whole front and top have vanished, and with the top have gone whatever buildings stood on it. To lay bare the whole of this would have been a task as futile as it would have been costly, for in most places there was nothing to find. The method adopted was to make cuts at intervals across the supposed line of the wall in order to verify the existence of the mud-brick rampart; if any of the true face was found, this of course gave the exact line, and where only the core survived, the line was at any rate approximate. Any buildings found on the wall-top were thoroughly excavated, and where the wall was difficult to follow, work was carried farther “inland” until, if possible, buildings were reached whose frontage might be assumed to run parallel with the direction of the wall.

The best-preserved part of the defences was on the east side of the town. Here the rampart still stands to its full height, and on it are the houses which formed the wall proper, their burnt brickwork surviving to several courses above floor-level. Brick stamps would date the houses in the reign of Sin-idinnam of Larsa. To the south of the main block of private houses there projects a very massively built fort, undated by inscriptions but certainly of the Larsa period, lying on the top of the rampart but separated from the wall line by a narrow space. Here the rampart widened out and had supported an important building, the lower part of which consisted of a solid mud-brick terrace faced with burnt bricks front and back. Of its interior walls nothing remained, but an elaborate gateway approach of Kuri-Galzu and heavy mud-brick foundations of a Neo-Babylonian fortress showed that whatever had stood here was an important element in the city’s defences.

Image Number: 191613

On the west side of the city there was a harbour, connected with the Euphrates and lying inside the wall line. An earthwork topped by a wall of mud-brick carried on the line of the rampart proper and formed the mole enclosing the harbour. At the north end this had been strengthened by a kisu, a solid cube of mud brickwork built up against its outer face at a later period, and also at a later period the harbour entrance had been blocked with mud brickwork; indeed the entrance was most difficult to find, but the discovery that at a certain point the bricks were of a slightly different size and had been piled in carelessly instead of being truly laid did finally enable us to distinguish the blocking from the original wall. The high terrace of the town sloped down very steeply to the harbour and clearly defined its area and shape, though cuts were made to show the exact line; a cut at the back of the harbour was taken down through muddy sediment to bottom level and exposed the burnt-brick footings of the mud-brick quay wall.

At the north end of the city there was a second harbour, the greater part of which could have been planned from surface indications, the low dark mounds of the moles being quite distinct; however, cuts were made across these and the outer face followed for some distance. Here again the enclosing line consisted of a mud-brick wall (of which not much survived) built along the top of an earthwork; the latter was of rubbish thickly revetted with mud containing much broken pottery. The eastern mole ran along a spit of land which extended for some distance to the outside, that is to the east, of it; the canal lay beyond this, leaving a flat level strip between it and the rampart, which it only touched by the angle of the eastern fort. Possibly the water originally washed the foot of the defences all along and had merely retreated; at one point we were able to distinguish in its silted-up bed another bank of what must have been an insignificant water-channel taking the place of the old navigable canal. I should remark that only one bank of the canal was traced by us, that nearest to the town; the width of its bed and what stood on its farther bank remain unknown.

Image Number: 198704

Image Number: 198705

Along the line of the wall there were found a number of graves of the Persian period, underlying the floors of houses which had themselves entirely disappeared. They consisted of terra-cotta coffins, bath-shaped with one square and one rounded end, in which were bodies sharply contracted, the length of the coffin little exceeding three feet. In these were found many glazed pottery vessels, unglazed bowls very beautifully turned and often of egg-shell thinness, beads of stone and glass paste or glaze, bronze fibulae, silver ear-rings and finger-rings, and one extremely fine silver bowl decorated with fluting and chased work [Plate VIII, 1]; this unique piece was supposed to be bronze, so thickly was it covered with cuprous oxide, and it was only after prolonged chemical treatment that its real nature was discovered; the same is true of three finger-rings, the preservation of which is no less remarkable than that of the bowl.

The private houses surviving on the wall-line were almost all of the Larsa period and presented few features of interest; below the floors were graves, some of which produced pottery typical of the period, but little else. The description of these must stand over for the final publication of the Expedition. In this preliminary report it is only possible to deal with the more important buildings whose excavation was incidental to the tracing of the defences.

Image Number: 191627

Image Number: 191628

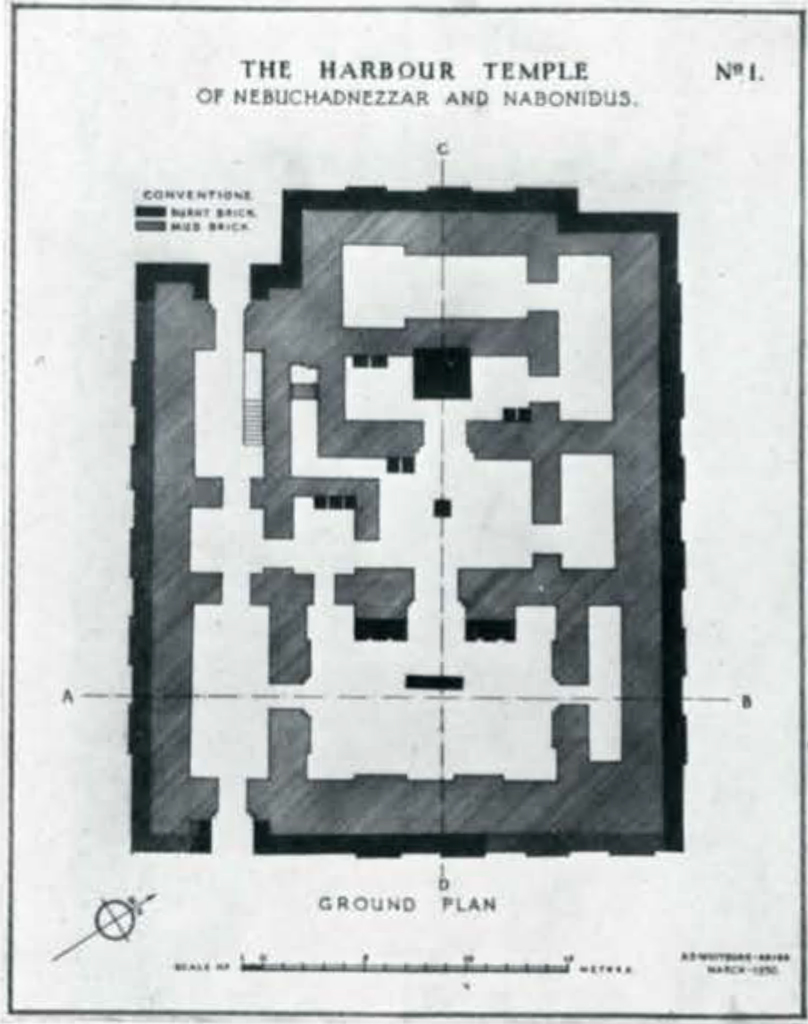

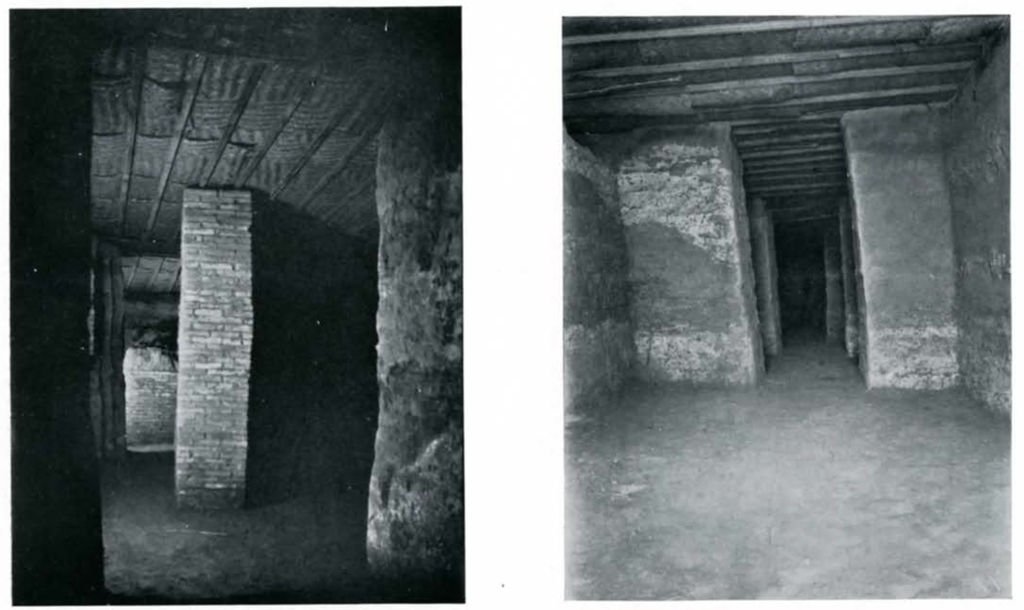

In the last week of the season we found and excavated a large temple lying in the corner of the North Harbour. Its site was marked by a low mound which had obviously been disturbed by seekers after treasure, and a few scattered bricks bearing the stamp of Nabonidus showed that the buried building was of late date. As it seemed to be important for defining the exact limits of the harbour, we decided to clear it, and were astonished to discover here the best-preserved of all the ruins of Ur. The temple [Plate VII, 1] is constructed in mud brick with a facing of burnt brick to the outer walls and certain interior details also in burnt brick; the walls are standing to a height of twenty feet, and on them the mud plaster and even much of the white-wash survive. In order to protect it from re-burial by the sandstorms of the summer months it was covered with a temporary roof, which gives to it a striking air of completeness [Plate IN. The temple stood close to the water or, more probably, on ground actually reclaimed from the harbour. It was founded by Nebuchadnezzar (about 600 B. C.) and was restored some seventy years later by Nabonidus. It would appear that the low-lying site was damp, fur Nabonidus filled in the whole building with clean soil to a depth of two metres or more and laid a new floor over this; he added certain burnt-brick features and presumably made an increase in the wall height corresponding to the rise in floor-level. Along one side of the building runs a corridor with a doorway at either end; side doors lead from it into the temple proper. This consists of outer court, pronaos and sanctuary, with a long “oracle-chamber” behind the sanctuary and service chambers down the northeast side, balancing the corridor on the southwest. The great altar in the sanctuary, set in a shallow niche, is of burnt brick, and in the sanctuary and against walls in the pronaos and in the outer court there are groups of burnt-brick “pilasters” which seem to be the cores for wood-panelling; their purpose is unknown. Two other features in burnt brick, one in the pronaos and one in the court, call for special mention. The first is a square pillar, the second a length of narrow walling. In other Neo-Babylonian temples at Ur, such as that which will be described next in this report, precisely the same features have been found, but as there were never more than two or three courses of brickwork left standing above pavement-level, their real character was disguised. I had supposed that the square block in the pronaos was an altar and the narrow block in front of the pronaos door was a “table of offerings,” as it certainly was in the Larsa-period temple of Nin-Gal, where the bitumen top of the table was preserved. But in the Harbour Temple now under discussion both these structures were found standing to the full existing height of the walls. There can be no doubt that in the centre of the promos we have a pillar supporting the flat roof, a point of considerable importance for the architectural history of the late period. The wall in the court is not so easy to explain; it is a screen which effectually masks the view of the sanctuary, and while it too may have performed some structural function it looks more as if it were intended for a screen, nor is it likely that there was any roof over the court requiring support. Another feature of interest is the staircase in the lateral passage. This was an addition by Nabonidus and does not seem to have any counterpart in the earlier building; it is built of mud-brick only. The stairs run up from the corridor, turn over the wall of the temple proper, and were carried on in wood over a narrow passage with a right-angled turn at its end. They must have led to a gallery or chamber above the entrance to the sanctuary and perhaps extending over the sanctuary itself, and suggest something in the nature of the medieval rood-loft. I do not know of any parallel to this elsewhere.

Image Number: 191610

No inscriptions were found in the temple giving its name or that of the deity to whom it was dedicated; it is possible that further research next season may throw light upon the question. Last winter there was only time for the excavation and roofing of the building.

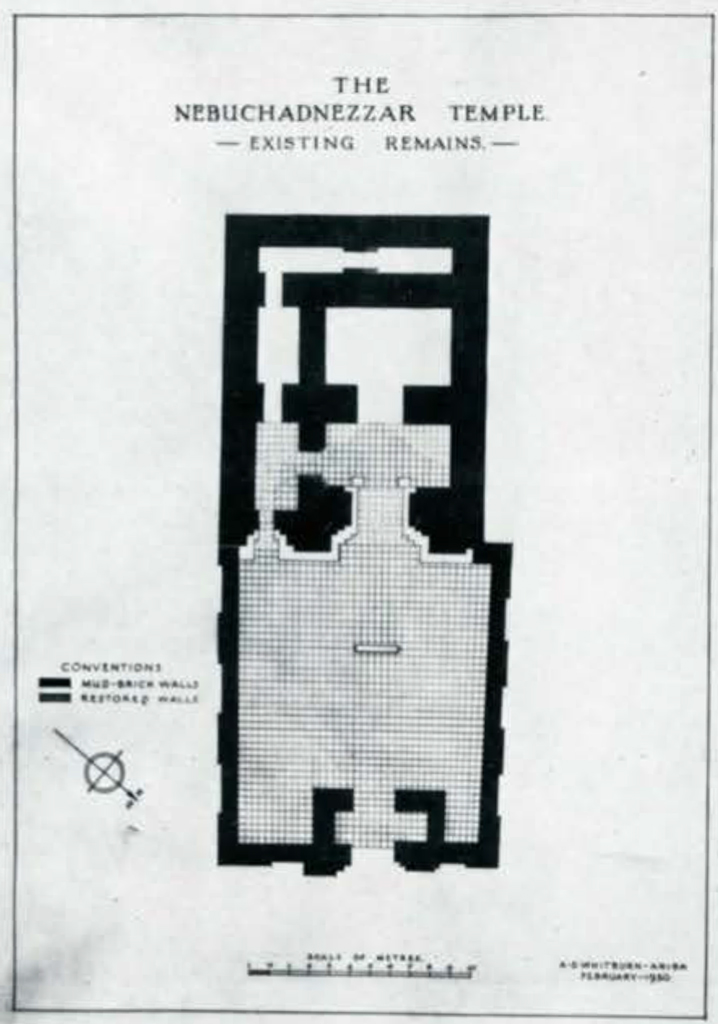

At the south end of the town, just inside the fortifications, another temple built by Nebuchadnezzar was found; not particularly interesting in itself, it acquired interest from the method of its discovery, which was one of the lucky accidents of archaeological work. The walls, all of mud brick, had been destroyed down to floor-level, and at the sanctuary end even the burnt bricks of the pavement had gone, leaving only the substratum of mud bricks; these scanty remains lay immediately below the surface sand, and when the men scraped the sand away only a mud-brick level was visible. A workman, rather smarter than the rest, noticed that the bricks were not uniform in colour, some being reddish and some grey, and that the patch of greyer bricks at which he was working began to take definite shape; then that between grey bricks and red there was a line of white about as thick as stout paper. Actually the red bricks were pavement foundation, the grey were walls, and the white was the whitewash which, applied to the surface of the upper part of the wall, now destroyed, had trickled down between wall and floor. On such evidence we were able to work out the complete ground-plan of the temple [Plate VII, 2], the only doubtful point being the precise width of the niche and the second was relatively poor; both were small single-chambered tombs lying at a level considerably higher than any others found. The unplundered tomb contained a wooden coffin in which was a man’s body; he had a gold-bladed dagger with a gold-studded wooden hilt and round his head no less than three of the normal head-bands consisting each of two lengths of gold chain and three large beads of lapis and gold. It seems fairly certain that these head-bands took the place of the modern Arab ageyl and were worn over a head-cloth, from which one can deduce that the head, like that of the Arab today, was clean shaven. In a corner of the coffin, well apart from the head, was a heap of dust preserving the texture of hair, undoubtedly the remains of a wig, and round this was a fillet of thin gold plate, while two gold hair-rings of the usual spiral type lay in the dust. The evidence that the Sumerian was clean-shaven and wore a wig on ceremonial occasions would explain the divergent representations in art which have puzzled archaeologists. From another grave was recovered a fine example of the court lady’s head-dress with the traditional wreath, in this case of long ribbed leaves with flower rosettes, and with a second wreath having circular pendants formed of gold wire spirals. The beads on the upper part of the body were particularly numerous, and the cloak was fastened with a fine gold pin. In the grave was a small toilet-box of mother-of-pearl and shell and lapis inlay originally mounted on wood; it had a swivel lid of mother-of-pearl and in one of its two compartments there was still the green paint used for the eyes.

Image Number: 191604

Image Number: 191603

A clay pot in the form of an animal on wheels (with a hole in front for a string to pull it along by), an object rather like an old Staffordshire milk-jug, is interesting as well as curious, for it belongs to the rare group of zoömorphic vases for which some writers have claimed a foreign origin; coming as it did from the lowest strata of the cemetery it carries the type back to an earlier date than any other example yet known, and makes the foreign attribution perhaps less likely [Plate XI, 1].

In 1926-27, when work was being done in this quarter of the cemetery, I reported the discovery of a limited number of graves which gave evidence of partial cremation; since then nothing of the sort had been remarked, but last winter more graves were found in which both the bones and the objects showed clear traces of fire. These graves date just before and just after the First Dynasty of Ur. They include both plain inhumation burials and clay coffin burials; they are confined to one rather outlying corner of the cemetery, and their contents are always poor. Probably they represent some particular element in the population of the town in the days of the First Dynasty; perhaps they were slaves, possibly foreigners.

Museum Object Number: 31-17-14

Image Number: 191543

But the main interest of the cemetery work lay in the evidence which was forthcoming for the date of the graves. From season to season there has accrued evidence, not all of which I have been able to publish in these preliminary reports, supporting the view originally put forward that the royal cemetery as a whole must fall between 3500 and 3200 B. C.; but the evidence did not amount to proof, and my conclusions were disputed in a good many quarters. I had already pointed out that between the Sargonid graves of the upper level and the royal cemetery proper there was a “barren stratum,” sometimes pierced by intrusive graves, of course, but everywhere recognizable; it was in this barren stratum that there was found the lapis cylinder seal of Nin-tur-nin the wife of Mes-anni-padda, king and the second was relatively poor; both were small single-chambered tombs lying at a level considerably higher than any others found. The unplundered tomb contained a wooden coffin in which was a man’s body; he had a gold-bladed dagger with a gold-studded wooden hilt and round his head no less than three of the normal head-bands consisting each of two lengths of gold chain and three large beads of lapis and gold. It seems fairly certain that these head-bands took the place of the modern Arab ageyl and were worn over a head-cloth, from which one can deduce that the head, like that of the Arab today, was clean shaven. In a corner of the coffin, well apart from the head, was a heap of dust preserving the texture of hair, undoubtedly the remains of a wig, and round this was a fillet of thin gold plate, while two gold hair-rings of the usual spiral type lay in the dust. The evidence that the Sumerian was clean-shaven and wore a wig on ceremonial occasions would explain the divergent representations in art which have puzzled archaeologists. From another grave was recovered a fine example of the court lady’s head-dress with the traditional wreath, in this case of long ribbed leaves with flower rosettes, and with a second wreath having circular pendants formed of gold wire spirals. The beads on the upper part of the body were particularly numerous, and the cloak was fastened with a fine gold pin. In the grave was a small toilet-box of mother-of-pearl and shell and lapis inlay originally mounted on wood; it had a swivel lid of mother-of-pearl and in one of its two compartments there was still the green paint used for the eyes.

A clay pot in the form of an animal on wheels (with a hole in front for a string to pull it along by), an object rather like an old Staffordshire milk jug, is interesting as well as curious, for it belongs to the rare group of zoömorphic vases for which some writers have claimed a foreign origin; coming as it did from the lowest strata of the cemetery it carries the type back to an earlier date than any other example yet known, and makes the foreign attribution perhaps less likely [Plate XI, 1].

Image Numbers: 191576

In 1926-27, when work was being done in this quarter of the cemetery, I reported the discovery of a limited number of graves which gave evidence of partial cremation; since then nothing of the sort had been remarked, but last winter more graves were found in which both the bones and the objects showed clear traces of fire. These graves date just before and just after the First Dynasty of Ur. They include both plain inhumation burials and clay coffin burials; they are confined to one rather outlying corner of the cemetery, and their contents are always poor. Probably they represent some particular element in the population of the town in the days of the First Dynasty; perhaps they were slaves, possibly foreigners.

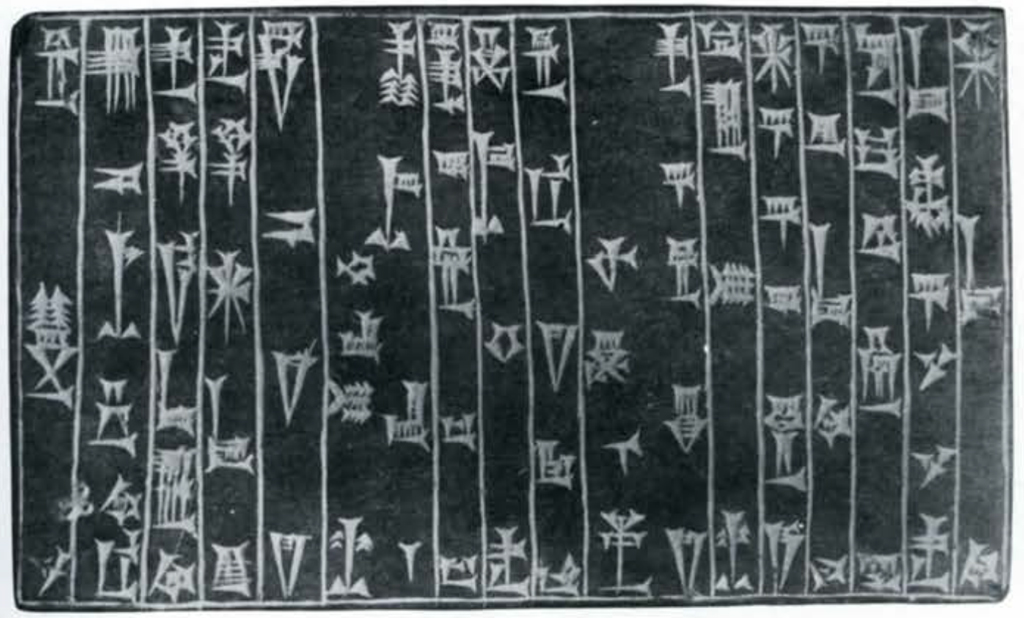

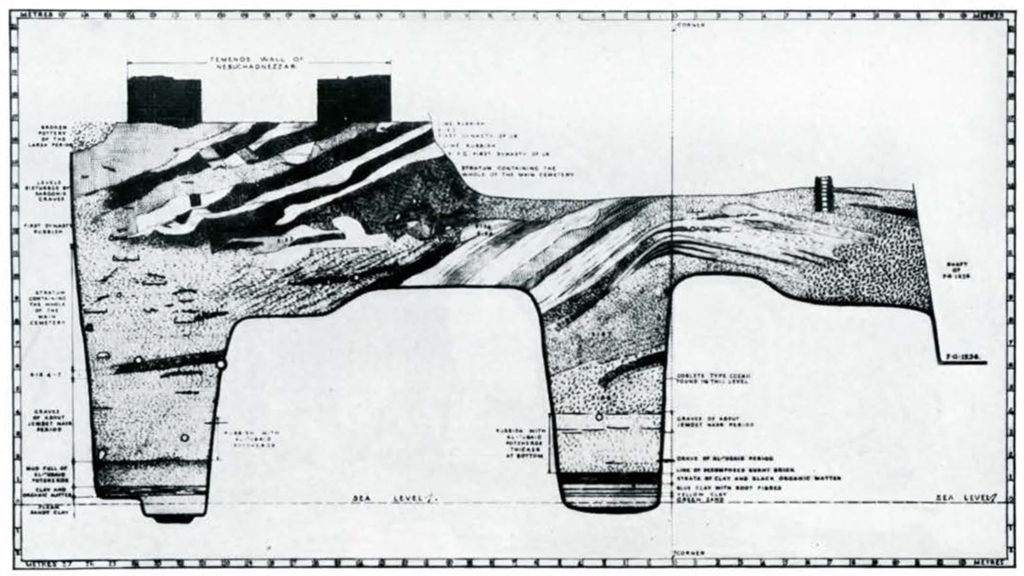

But the main interest of the cemetery work lay in the evidence which was forthcoming for the date of the graves. From season to season there has accrued evidence, not all of which I have been able to publish in these preliminary reports, supporting the view originally put forward that the royal cemetery as a whole must fall between 3500 and 3200 B. C.; but the evidence did not amount to proof, and my conclusions were disputed in a good many quarters. I had already pointed out that between the Sargonid graves of the upper level and the royal cemetery proper there was a “barren stratum,” sometimes pierced by intrusive graves, of course, but everywhere recognizable; it was in this barren stratum that there was found the lapis cylinder seal of Nin-tur-nin the wife of Mes-anni-padda, king of the First Dynasty of Ur. In the area dug last winter this barren stratum was most noticeable, so well defined by its colour that a photograph of the side of the cutting made by the excavation shows it clearly. It will be remembered that the royal cemetery was dug down into the rubbish-heaps of the earlier town. Where there has been no subsequent disturbance of the ground the sloping strata of ashes, pottery, decayed brick, crumbled mud brick, and so on, are perfectly obvious; where graves have been dug the stratification has of course been destroyed in the process. On Plate XIII is shown the section of the cemetery area visible on the southwest limits of our excavated area. The upper light bands labelled s.i.s. i and ii are, with the dark band between them, the “barren stratum” of my earlier reports; below them comes a broad confused belt, with no interior stratification, in which lie all the graves of the royal cemetery (the belt is here not so thick as it is farther to the east, where it goes considerably deeper), and below it is a well-defined dark band labelled iv, v. The strata s.i.s. z and a are composed of light-coloured lime rubbish and broken pottery, and the band between them is chiefly of ashes and broken pottery; they are roughly contemporary and were probably of quick growth. In them were found a few tablets and numerous clay jar-sealings bearing the impressions of cylinder seals, and amongst these were examples bearing the names of Mes-anni-padda and of his wife Nin-tur-nin. Strata s.i.s. x and a therefore date from, or immediately after, the First Dynasty of Ur. They run unbroken over the royal cemetery, the grave-shafts of which were dug from a ground-level that existed before the First Dynasty rubbish was dumped here; the latest graves of the cemetery therefore date from before the First Dynasty of Ur. (See Appendix by The Reverend E. Burrows, page 106, with plates XX and XXI.)

Museum Object Number: 31-17-8

Image Number: 191533

Museum Object Number: 31-17-7

Image Number: 191535

The lowest graves of the cemetery are cut down to or into, but never go right through, the dark stratum iv—v, which is composed of decayed red brick, pottery, and clay jar-sealings.2 Here were found more tablets and seal-impressions very different from those found above the cemetery. The tablets bear a script which is semi-pictographic, more archaic than that of the seal-cylinders in the royal cemetery, rather more advanced than that of the tablets from Jemdet Nasr, which were found in association with three-colour pottery. The seal-impressions are most remarkable, and on them there are, as one might expect with objects of a character less directly utilitarian than tablets, more obvious survivals of the old pictographic writing. The collection made from this stratum is more fully described by Father Burrows in a separate section of the report; here I would only emphasize one or two non-epigraphical points. The stratum s.i.s. iv (with which goes s.i.s. v, scarcely to be distinguished from it) was formed and was buried beneath accumulated rubbish to a depth of at least five and a half metres before the cemetery came into being, for it is in that accumulated rubbish that the graves are made; there was therefore a sensible lapse of time between the depositing of the stratum s.i.s. iv and the digging of the earliest graves. In the stratum s.i.s. iv and belonging to it there were found four copper bull’s feet from a large statue of which the body probably had been in wood; their style and technique are identical with that of metal sculptures from the royal tombs, and they prove that the culture represented by the seal-impression stratum is simply an earlier stage of that illustrated by the tombs—the static character of Mesopotamian culture is a commonplace. The stratum is unbroken; the lowest graves were cut down into it (the stone tomb PG/1631 fairly deeply and the great stone tomb PG/1236, found the season before last, more deeply still), but not through it; it forms a very definite division between the confused zone containing the cemetery and what lies below it, but it does not belong in time to the latter, because below it again comes a confused zone containing graves which were not cut through s.i.s. iv but dug down from a surface on which s.i.s. iv was subsequently deposited. The facts of stratification therefore show that on piercing the level in which the seal-impressions occur we must expect to find something materially older than they are.

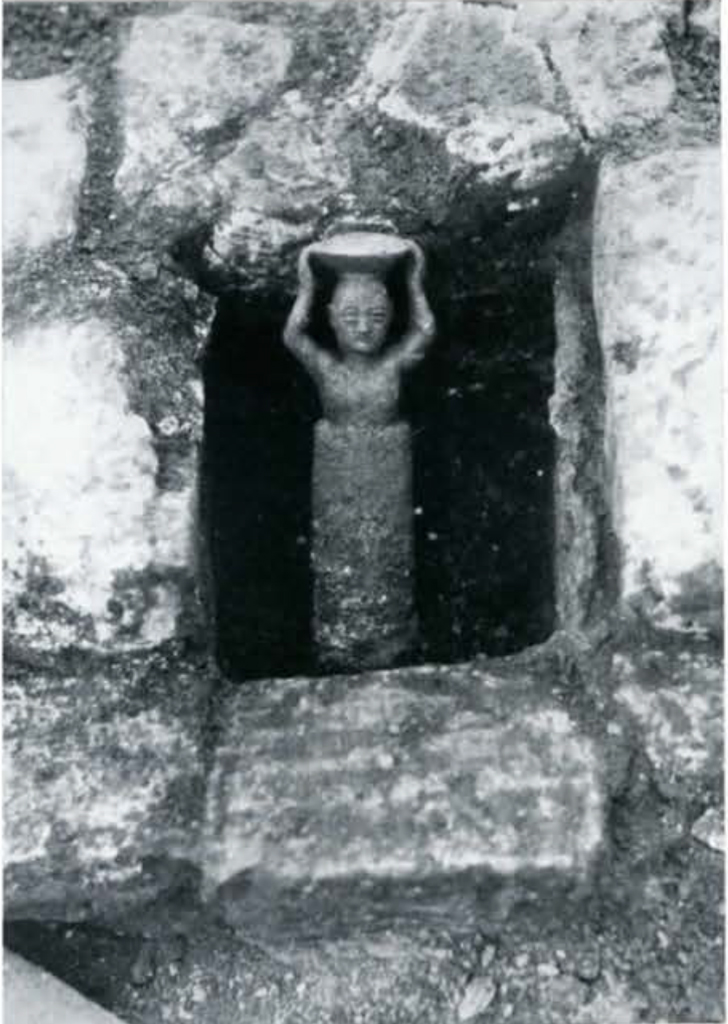

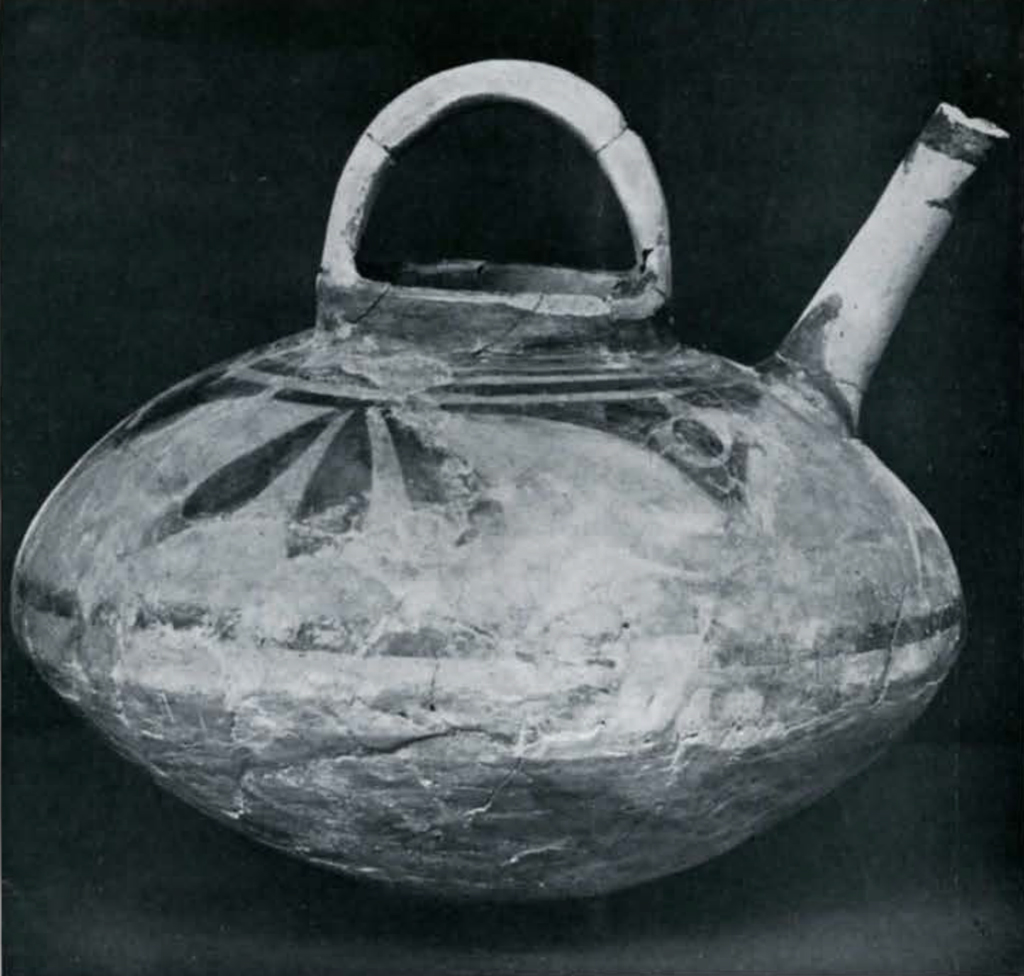

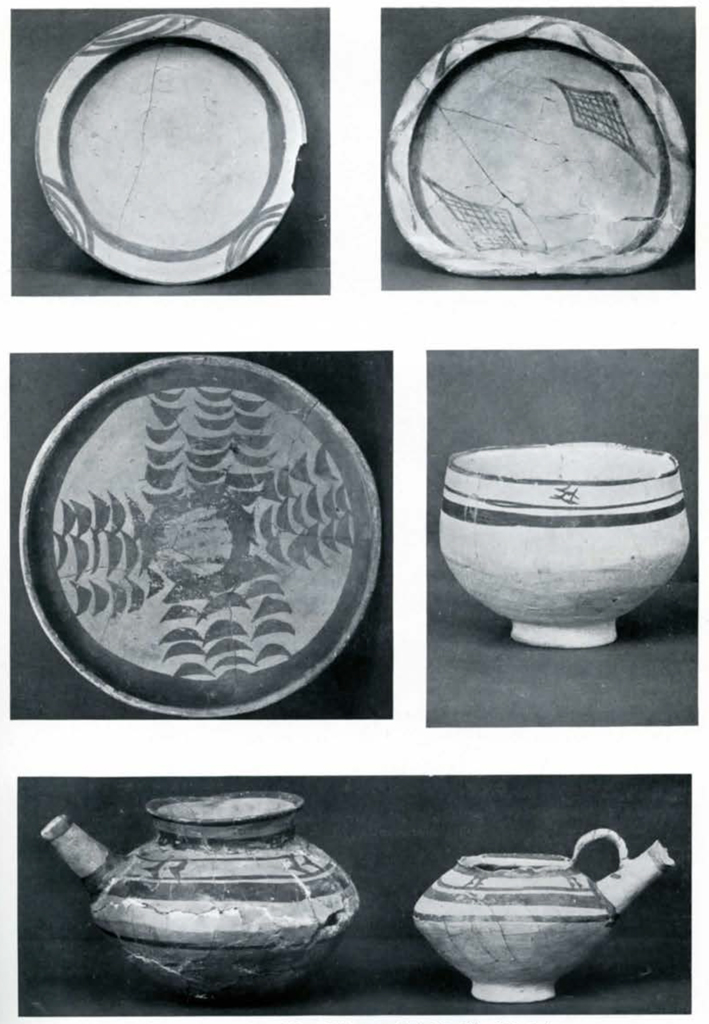

What we did find was a new series of graves different in every respect from those of the royal cemetery. The bodies are definitely contracted, instead of being laid on the aide with the hands brought up to the face and the body straight with the legs slightly bent in the attitude of a person asleep, the invariable rule in the royal cemetery and for long after that; the hands indeed are brought up close to the face, but the backbone is bent and the legs so flexed that the knees come parallel with the chin and the heels almost touch the pelvis [Plate XII, 2]. Such a divergence in the ritual of burial must imply a great difference in time or in religious belief or in race. The contents of the graves (of which thirty-five were found crowded together in a small area) are no less striking. Stone vessels were abundant and of types not found in the royal cemetery, lead cups were common in the place of the copper or bronze vases of the later period, and the clay vessels were all of new types marked by sharply angular outlines, lug handles and spouts [Plate XI, 2], while a pot of plain red burnished ware, resembling fragments which in the winter before we had found associated with sherds of painted Jemdet Nasr pottery, seemed a final argument for assigning the graves to that cultural phase which on other grounds would well fit in at this point of our archaeological sequence. This theoretical attribution was proved correct when a large pot from one of the graves, entirely covered with a coat of earth and salts, was cleaned in the British Museum laboratory and found to be decorated with the three-colour geometrical design characteristic of the Jemdet Nasr wares.

Image Number: 191521

Image Number: 191519

As work went on, the soil in which the graves were dug began to yield fragments of the black-on-white pottery of al-‘Ubaid, which grew more numerous as deeper levels were cleared and continued until virgin soil was reached at about modern sea-level. The approach to virgin soil was heralded by alternate thin strata of black mud and greenish sandy clay; the true virgin soil was clay of a stiffer texture.

A second deep shaft was sunk by us farther to the northwest [see sectional drawing, Plate XIII] and gave consistent results. Here the cemetery zone had already been excavated in 1926-27; it lay higher than to the south and east, consistently with the slope of the original rubbish-heaps of which this was about the highest point, but the same underlying strata were encountered. Jemdet Nasr graves were found on the level of those in the first shaft. A little below these was a single grave of the al-‘Ubaid period containing a particularly fine handled and spouted pot with a curious design in black on a white ground [Plate XII, 1], and a plain hand-made vase with handle and trumpet spout. The grave lay half a metre above virgin soil and a metre and a half above sea-level. The excavation enabled us to assign the hitherto isolated Jemdet Nasr ware to a definite place in a sequence in relation to the royal cemetery on the one hand and the al-‘Ubaid pottery on the other.

It was at first disconcerting to find that in these two shafts, sunk to virgin soil, there was no trace of the clay Flood-deposit, discovered the winter before only a short distance off to the east. The seeming anomaly can be accounted for in a way which explains what would otherwise have been a further difficulty. The rubbish-heaps into which the Jemdet Nasr graves were dug are shown by the pottery in them to be of al-‘ Ubaid date and must therefore be largely if not entirely pre-Flood; the top of this rubbish-stratum is as high or higher than the top of the clay deposit farther east. The slope of the strata from north-northwest to south-southeast and again from west to east shows that the pre-Flood rubbish-mounds thrown out from the inhabited island-site formed a sort of promontory running out from the island on the line given by our two shafts. Our pits sunk in 1928-29 on the northeast, that is, on the up-stream, side of this produced an eight-foot deposit of clay; last winter’s excavation to the northwest, on the edge of the inhabited island (to be described later) produced an eleven-foot deposit of sandy silt. I would suggest that the rubbish-promontory, obstructing the course of the flood in a main channel, caused a back-water eddy resulting in the deposit, up to its own height, of the heavier silt borne by the water; elsewhere a smoother current deposited in a normal way its lighter content. And here a further caution seems to be called for. We have not yet made any trial pits in the plain to trace there the work of the Flood, but it is not to be supposed that over the plain the silt would attain anything like the depth that it does on the town site. Ur was an upstanding island and, like a tree-branch caught in a stream-bed, would intercept the silt and cause the formation of a much larger mound; over the plain the unimpeded waters would pass carrying the bulk of their silt down to the sea; the depth of sand found piled against and over the island is no criterion of the Flood’s effect on the country at large.

Museum Object Number: 31-17-296

Image Number: 191518

The Flood Excavation in the Town Area

The third part of our programme at the beginning of the season was to substantiate and add to the evidence already at hand for the historical character of the Flood, evidence derived from small pits sunk through the rubbish-heaps of the cemetery area. It was necessary to work on a larger scale and if possible at a point where house-remains would give a stratification more suited than that of rubbish-mounds to chronological argument. In order to simplify the process, I chose a site behind the cemetery and relatively low-lying. Work done here in previous seasons had shown that the area was much denuded by weather in later times and that the modern surface was reduced to that of what we called “Prehistoric terraces,” that is, a ground-level older than the First Dynasty of Ur; here then we could expect quick results.

The area marked out for excavation was a rectangle measuring twenty-five by sixteen metres; the sides were cut as straight as the soil allowed; the maximum depth reached was 19.30 metres. The drawing on Plate XIV gives a medial section through the length of the pit (southwest by northeast) and is based on elaborate measurements and notes; the small section is of the northeast end of the pit along a parallel line farther to the southeast, almost against the pit’s side, where it happened that more early graves were encountered. In the upper part of the excavation eight distinct building levels were found; walls were of mud brick, floors of beaten clay, and these were in such good condition that no confusion of strata was possible. Plans were made of the buildings in each level, but being of little intrinsic interest are not published here. It should, however, be remarked that as the walls were well-built and sometimes particularly solid, attaining a thickness of as much as four metres, a fairly long floruit should be assigned to each level, and the total lapse of time represented by the eight levels must be considerable.

Image Number: 191606

The uppermost level contained buildings whose walls were constructed not with shaped bricks but with lumps or basketfuls of stiff clay set in clay mortar, a form of terre pisée building which we sometimes find in the shaft-constructions of the royal cemetery, and in this and the succeeding level, in which the walls were of plano-convex mud bricks, the pottery was just what may be found in the earlier graves: stone vases and a few copper tools showed similar analogies. Further evidence was given by the pottery ring-drains which were numerous at this level. Most of them could be dated by the pottery packing which filled the space between the rings and the sides of the circular shaft in which the drain was contrived, and while some of them were as late as the Larsa period the majority could be attributed to the First Dynasty of Ur. Now these seepage drains may vary in length from five to ten metres or more; few even of the earliest found here went down more than three metres below the modern surface, and it can fairly be assumed that the houses which they served stood on a level at least two metres and probably four metres above that modern surface. We have then to allow for a vertical interval of at least two metres between the highest surviving ruins and the foundations of the walls of the First Dynasty of Ur, and at a normal rate of accretion must date our ruins certainly not later than 3200 B. c.; if the interval was twice as great (as it probably was) the highest ruins must be correspondingly earlier. The evidence of the pottery and other objects will not allow of our assuming more than the three upper levels of buildings to be synchronous with the royal cemetery.

At 1.25 metres down, but let into the floor and therefore belonging rather to the level above, namely A, were some burnt bricks not plano-convex but flat and closely resembling those used in the vault of the tomb of Queen Shub-ad; at 1.40 metres down was a burnt brick, also flat but with a long finger-made groove in its upper face, a type never found in the cemetery. The walls of the second and following strata were of mud bricks, plano-convex and often laid herring-bone fashion [Plate XV, I].

Image Number: 191608

In stratum E, on a well-made clay floor at 12.40 metres above sea-level, there was a large collection of stone and clay vases. The clay pots, of which many were spouted, were decorated with cable mouldings on the sharply defined shoulder, with “gashed” ornament, and with incised hatching. Many were of “reserved slip ware,” that is, the vessel had been dipped before firing in a bath of thin slip and this had then been wiped off in streaks, leaving a rough pattern made by the contrast between the liner and lighter coloured slip and the darker and coarser body-clay. All these types are strange to the cemetery.

At 10.80 metres above sea-level there began to occur a tall slender clay goblet set on a short stem with circular foot; fifty centimetres lower down it was the commonest type found, the broken examples numbering hundreds; at 9.70 metres it disappeared. This type, equally common and equally short-lived, is found at Kish between five and six metres below plain level.

At this level, incised wares were common. At 9.80 metres came the first example of Jemdet Naar three-coloured pottery and several of buff or pink ware with horizontal red paint bands; a few examples of plain burnished red went with these, and by 9.80 metres above sea-level a plain plum-coloured unburnished ware which had occurred sporadically in higher strata was fairly common. At 9.20 metres began a pink ware with horizontal chocolate bands which is probably only an accidental variant of that with red bands on pink or buff; it was common down to 8.60 metres, and thereafter was found, but less frequently.

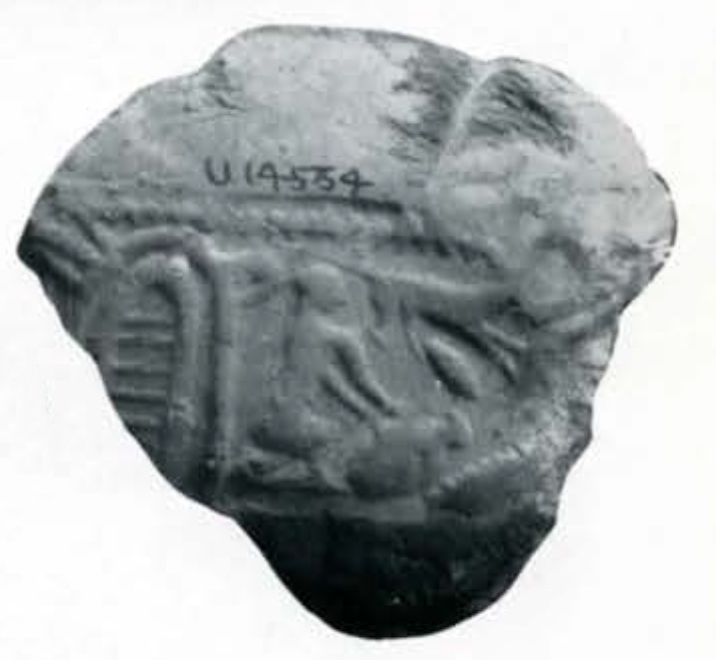

At 9.80 metres above sea-level there were found fragments of a small bottle of glazed hit, originally blue but now bleached to a yellowish white; it had a pear-shaped body and broad flat rim, and was decorated on the shoulder with impressed chevrons. On the same level were two clay jar-sealings with impressions of the naturalistic type found in “Seal-impression stratum iv” in the cemetery pit between the tomb stratum and that of the Jemdet Nasr graves; a similar seal-impression was found at 8.60 metres above sea-level and two more as low down as 7.60 metres.

Image Number: 191465

Image Number: 191470

On the 8.80 metres level there were found three fragments of Jemdet Nasr pottery, and the proportion in which it occurred in relation to the other decorated wares, pink ware with red banks, plain burnished red, and plain unburnished plum-coloured, rapidly increased until on level 8.30 metres it predominated over the sum of all these. Immediately below this, at level 8.20 metres, it disappeared over almost the whole area, and though in one part of the excavation it continued down to 7.80 metres this was the lowest point reached by it. At Kish the Jemdet Nasr pottery comes immediately below the slender goblet type, at 6 metres below plain level, and continues to 7 metres.

Museum Object Numbers: 31-17-289

Returning to the sectional drawing, we shall see that the slender goblet type, the incised wares, and the burnished or unburnished plain red correspond to the lower building levels, where there had also been a change in the size and shape of the bricks in the walls, which were now flat instead of plano-convex. At 10 metres above sea-level the buildings stopped and there began a belt nearly five and a half metres thick composed of ashes and broken pottery; embedded in this were the remains of potters’ kilns, lying one above the other and proving that an industry bad been practised here for generations. It is in the upper part of this stratum, made up of wasters from the kilns and the ashes from their furnaces, that we find first the pink pottery with red bands and then the Jemdet Nasr wares. All these vessels were wheel made, and at 9.90 metres above sea-level there were found the fragments of a potter’s wheel made of clay, a thick disc with its pivot-hole smoothed with bitumen and small holes near the circumference at one point, doubtless for the stick which served to turn it; it was a wheel heavy enough to spin of its own momentum. The kilns were built of fire-clay which by the heat had been turned into slag coloured from red through yellow and green to white. In one of them the vessels for the last firing were found stacked inside, still in place [Plate XV, 2]; they were rough hand-made bowls with straight walls and flat rims (the same type occurs in the fifth archaic level at Warka and also at Nineveh). Since this was the highest of the kilns the technique is really a survival, but lower in the stratum a complete change took place and we pass from wheel-made to hand-made pottery. At level 8.60 metres the first two sherds of al-‘ Ubaid ware occurred, and three more in the next fifty centimetres (except that at the southeast end of the pit there was at 8.30 metres a sort of pocket containing a fair number of fragments); between 8.10 metres and 7.50 metres there were perhaps a dozen. Below this the al-‘Ubaid fragments were about forty per cent of all the coloured wares, the rest being plain red nearly always burnished but with a few plum-coloured pieces; between 7.30 metres and 6.80 metres there were counted sixty-four of al-‘Ubaid as against seventy-nine red, between 6.80 metres and 5.20 metres three hundred and seventy-nine as against one hundred and fifty-five, and below this virtually the whole of the painted pottery is of the al-‘Ubaid type.

A burnt brick found between levels 7.80 metres and 7.30 metres above sea-level was flat and thin with two small holes drilled through it towards one end; the type has been noted at Kish. At level 8.60 metres there was found a rectangular flat brick measuring twenty-one by nine and a half by six centimeters, made of cement; at 7.70 metres [Plate XVI] there was a circular basin, perhaps used for puddling the potter’s clay, lined with cement bricks measuring forty by eighteen by eleven centimetres, and bricks also of cement measuring twenty by eight by eight centimetres were found at level 6.60 metres. That cement bricks should have been employed at this early period is a most remarkable fact—that it was no unusual thing is shown by our excavations at Meraijib.

The kiln stratum produced, besides vast quantities of pottery, a few copper tools, clay tools, smoothers, etc., used in pot-making, a few beads, chiefly clay copies of the long spirally-marked beads cut from the core of the conch shell, cones for wall mosaic, and three objects calling for special notice. One of these, found at 7.90 metres above sea-level, was a bowl of glazed frit, broken but nearly complete, and preserving the pale turquoise colour of its glaze. Contemporary with the Jemdet Nasr pottery, this is the earliest example that we know of a glazed vessel (though earlier glazed beads are found in Mesopotamia and probably in Egypt, though synchronization for such periods as this would be hazardous, to say the least), and may well raise the question whether such were first manufactured in the Euphrates valley. Ten centimetres lower down in the same stratum was found a remarkable cylinder seal of dark steatite, the oldest that we have in a well-authenticated setting. Its archaic character [Plate XVIII, 2] is obvious, but the subject is difficult to determine. On exactly the same level as the cylinder seal was found a steatite carving in the round of a wild boar [Plate XVIII, 1], an astonishing work of art of the Jemdet Nasr age. The animal is represented as crouching down with its chin resting on its fore hooves; the modelling is admirable, and the very definite convention which informs the work is relieved by touches of vivid realism, as, for instance, by the way in which the upper lip is drawn up in folds to expose the tushes. A flat groove running under the belly and up the flanks was clearly for a support; by analogy with later representations of animals, in which they are so often associated with bushes or water-plants, it is not unreasonable to suppose that the support took the form of flat reed-leaves in copper or gold—the boar would then be shown crouched in a reed-bed, his natural lair. In the top of the beast’s back there is a cup-like hollow with raised rim; whether this was to hold a liquid used in religious ritual, as has been suggested, or was a socket for a statuette of a god, as seems to me more likely, there is nothing to show. Figures of couchant animals with a similar socket in the back occur nearly as late as the Third Dynasty of Ur.

At about 4.50 metres above sea-level the kiln stratum ceased abruptly, and we came upon a stratum more than three metres thick of clean water-laid sand. It shows no internal stratification, is uniform almost throughout its whole thickness (there is near the top a darker hand which may indicate a temporary surface, and there are one or two “pockets” of darker soil and rubbish which are strictly contemporary with the sand and merely result from an eddy), and, corresponding as it does with the heavier clay belt farther to the east, must be like it the deposit left by the great Flood.3 It rested on a stratum of irregular thickness composed of refuse resulting from human occupation—ashes, decayed mud-brick, potsherds, etc. This went down almost to sea-level; below it was a belt about one metre thick, of mud, grey in colour above and darkening to black below, much of which was clearly due to the decay of vegetation. In it were potsherds, sporadic above but becoming more numerous lower down and massed thickly at the bottom, all the fragments lying horizontally; they had the appearance of having sunk by their own weight through water into soft mud. At a metre below sea-level came stiff green clay pierced by sinuous brown stains resulting from the decay of roots; with this all traces of human activity ceased.

Image Number: 191467

Museum Object Number: 31-17-16

Image Number: 191565

Evidently this was the bottom of Mesopotamia. The green clay was the floor of the original marsh bordering the island occupied by the earliest settlers in this part of the valley; it was dense with reeds, and the mud of the stratum above was due to the decay of their stems and leaves and to the throwing into the water of

rubbish from the island, this of course including the broken pottery. Such accretion slowly raised the bottom of the marsh until it came above sea-level; as soon as this occurred and dry land was formed (the surface of the mud was more gritty and rather like gravel), the occupants of the island spread down over it. At the northeast end of our excavation the accumulation of debris was divided horizontally by three definite floors of beaten clay, showing that occupation had been continuous for a fairly long period. At the southwest end there was a heap of fallen bricks from a pre-Flood building. The bricks, originally of crude mud but hardened by some accidental conflagration and thereby preserved, were flat and rectangular, set in mud mortar. At a point half-way across the excavated area there was a mass of clay lumps burnt red and black; each lump was smooth on one side, and there either flat, convex, or concave, and on the other side bore the deep imprint of reed stems; they were fragments of clay daub from a reed building. On the strength of discoveries made at al-‘Ubaid I had previously pointed out that the characteristic hut of the pre-Flood Mesopotamian would be just that hinted at by the Utanapishtim legend in which the god, speaking to the hero’s house, apostrophizes it as “Reed-hut, reed-hut “—a structure of reeds and mats plastered with mud: here we have the remains of precisely such a structure. What is of peculiar interest is the fact that the fragments of clay are not all flat on the outer surface, but often rounded. The hut would be built as such huts are built today: a framework would be put up of fascines of reeds tied together, and over this would be fastened mats, either of woven reed leaves, as is ordinary now, or of parallel reed-stems, the type of mat common in North Syria. Here we have parallel reed-stems probably tied on to horizontal cross-pieces. The coating of clay did not obliterate the structural features of the building; to judge from the fragments found it emphasized it rather than otherwise, and the vertical fascines were reproduced as attached half-columns, the horizontal bands as plain moulding. The flatness of the mud wall was therefore relieved by a system of ornament which corresponded exactly to the lines of its structure. If that is so, we can argue from it to a real architectural sense in the builders of the pre-Flood era. I would further suggest that this primitive wattle-and-daub construction is at the bottom of that convention whereby, in the Larsa period and later, the walls of a temple may be decorated with attached half-columns. I have attributed this form of ornament to the influence of half-timber construction on brickwork; that I believe to be correct, but the frame-and-matting hut is simply a cheaper variant of the half-timbered house, and the mud plaster affords analogies which the bricklayer would be more apt to follow.

Museum Object Numbers: 31-16-734 / 31-16-733

Image Numbers: 191498, 191500 , 191497, 191499

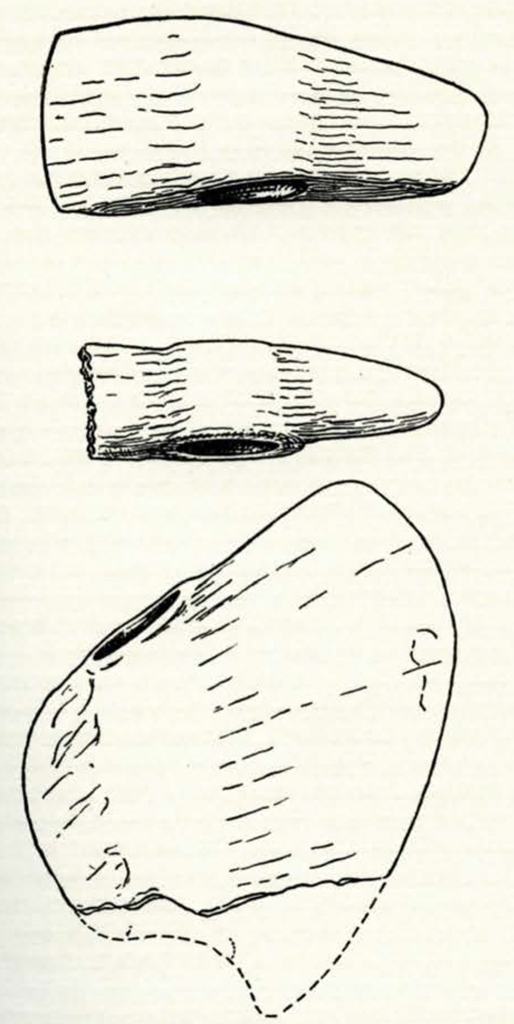

The house debris of the antediluvian level produced besides pottery, numerous stone pounders and grinders, flint hoes, a fragment of a finely polished black-and-white marble vase, clay sickles, clay models of tools of which the originals were certainly in metal [Figure A], steatite beads, shell beads, and two beads of amazon-ite, the nearest known source of which is the Nilghiri hills of central India, though it is found also in Transbaikalia. These would seem to point to an overland trade which, in the pre-Flood age, must strike us as amazing. The clay cones for wall mosaic occurred here as in the higher levels and gave further proof of sophisticated culture.

The pottery of the pre-Flood occupation level was of the types known to us at al-‘Ubaid. Here, and more noticeably in the marsh stratum, the thin wares decorated with black on white or green tended to have ornament lavishly spread over the whole ground, bold in design with occasional intrusion of naturalistic and animal motives. With them there were plain hand-made vessels of very light drab clay, for the most part thin and skilfully turned, and fragments of large jars with thick walls and decoration in black or greenish drab or in chocolate on pinkish drab clay. Many of the pots were spouted, and a fair proportion had loop handles across the mouth. The vertical reeded handles of the Jemdet Nasr stratum were absent in the purely al-‘Ubaid level. But about the pottery of the early period the fullest information was given by the graves.

In the sand deposit left by the Flood there were graves. Some of them lay high up in the deposit, between levels 2.50 and 4.50 metres above sea-level, then there was a definite gap, and a fresh series of graves going down through the occupation stratum almost to sea-level. The latter must have been dug when the top of the sand formed the ground surface; the former when a considerable layer of kiln rubbish had formed above the sand; the different levels must correspond to a difference in date. That this was so was proved by the pottery. In the lower graves the painted pots were in the majority, and their decoration was generally rich, with a tendency to cover the surface; even in the plainest types, the cups, the field between horizontal bands of colour was relieved by the introduction of small decorative elements, and in the open plates a filling-ornament would occupy part of the ground within the black border. In the upper graves there was never more than one painted vessel, a cup, and that would bear nothing more elaborate than a plain horizontal band, while of the plain vessels, often numerous, the most common type was a sort of chalice on a splayed foot which was never encountered at the lower level. The graves represent two late stages in a culture of which the earlier is given by the contents of the occupation-level and the marsh. The progressive degeneration of ornament and the introduction of certain new types of plain pottery are the most obvious distinction of the stages, but comparison with the remains found at al-‘Ubaid itself suggest that the earliest stage was further marked by the prevalence of incised decoration and combed wares.

Museum Object Number: 31-16-677

Image Number: 191408

Image Number: 191409

Museum Object Number: 31-16-623

Image Number: 191422

Image Number: 191413

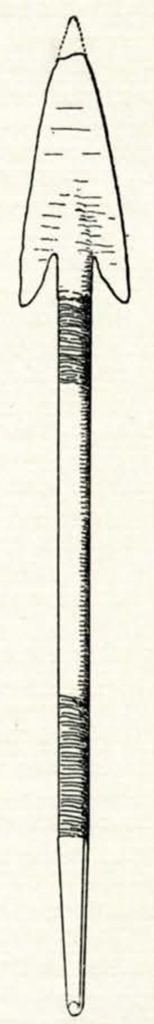

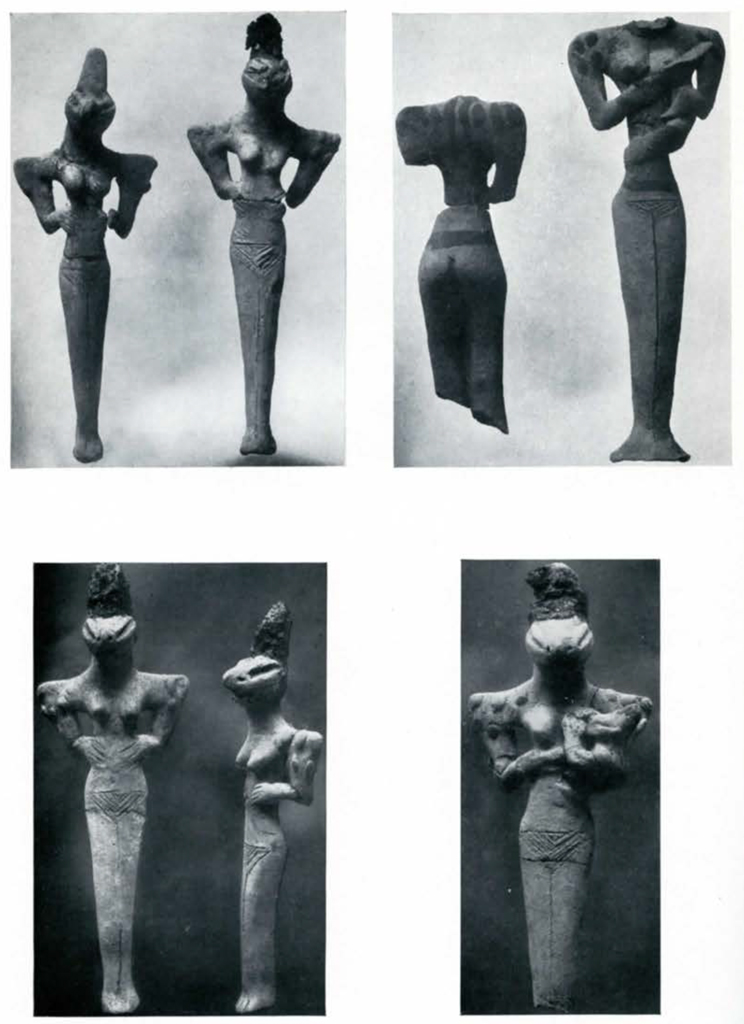

Turning to the graves themselves, the most surprising feature is the attitude of the body: the skeletons all lie on the back, rigidly extended, with the hands crossed over the pelvis, a position not found at any later date. Of the upper series, the furniture consists of one cup of painted ware, with simple horizontal bands, one or more open plates of plain light drab ware, and one or more chalices of drab or red clay; sometimes there is a bottle with globular body and upstanding rim. On the body there may be necklaces or armlets of small ring beads in white shell or steatite. In two graves there were squat pear-shaped mace-heads of limestone and steatite; in one a fine polished stone hammer-axe and in one a copper spearhead of harpoon type [Figure B]. The graves of the lower series were more elaborate. Sometimes the bottom of the pit was paved with fragments of pottery making a rough mosaic on which the body was laid; painted pots predominated, and there was considerable variety in shape both in these and in the plain wares (the chalice, as already stated, did not occur), and the “kettle,” with long spout and ring handle, was particularly common. Beads showed little change from the later period, and no weapons were found. But the most remarkable objects were the terra-cotta figurines, of which six were recovered from the graves [Plate XIX], while fragments of similar figures were found in the occupation-stratum below, to prove that in this respect the people of the earlier grave-group were carrying on a tradition which goes back to the pre-Flood age. The figures vary in height from fourteen to seventeen centimetres. Some are of hard-burnt greenish clay, with markings in black paint, others of soft, lightly fired, white clay originally coloured after firing with red and black paint, nearly all traces of which have disappeared, and these have wigs of bitumen applied to the head. All the figures are female, nude, and either holding an infant to the breast or resting their hands on their hips; in all cases the body is well modelled, though there is a conventional exaggeration of the width of the shoulders in contrast to the slender proportions of the rest. The head can only be described as monstrous: the back of the skull rises in an elongated dome (which in the infant is flattened into a fan shape), while the face is more reptilian than human, with eyes set violently aslant. Personally, I cannot believe that the artist who showed such skill with the bodies could not have succeeded better with the beads, supposing that his intention was to represent women, and I am driven to think that the grotesqueness is deliberate and that the subject is some kind of half-human demon. That the figures have a religious significance is certain, and if they really represent a bestial type their importance as documents for the pre-Flood religion is even greater. One head, found below the Flood level, is of a different type, the face being round and flat and the eyes horizontal, but in this also there is the queer elongated formation of the skull. On the painted figures there are black bands round waist, wrists, and neck, but these probably represent belts and strings of beads, and need not imply any dress; certainly the other figures are definitely nude. On the shoulders of all, both back and front, there are marks which in the painted figures are in black, in the others rendered by small attached lumps of clay; these I take to be coarse tattooing, like the cicatrices of some modern tribes of savages.

At 5 metres above sea-level there was found a figurine of a bird with outspread wings, of green clay with black paint markings, intended to be mounted on a stick passing through a hole in its body. At various depths there were animal figurines, mostly of sun-dried clay, some of baked clay with black paint markings; they represent domestic animals, sheep, goats, cattle, and dogs, and presumably have some religious significance.

A little further light was thrown on the late al-‘ Ubaid period by some experimental work done at a site called Meraijib, about eleven miles to the south of Ur. Our attention was drawn to it by the discovery, made by native seekers after treasure, of a grave containing fine stone pots very similar to those from our Jemdet Nasr graves. With the approval of the Director of Antiquities, work was undertaken on the site, which, however, proved to be too denuded to repay excavation. The pottery was a mixture of al-‘ Ubaid painted wares, with some red burnished pottery, and much having incised decoration; a few examples of the later “reserved slip ware” were also found. The buildings, of which little survived, were con-structed, at least as regards the lower part of the walls, of rectangular cement bricks resting (for the mound on which they stood was of loose drift sand) on a mud-brick platform. In one of the houses there were found stone grinders which had evidently been used with a bow drill for hollowing out stone bowls; in another there were quantities of clay roundels, each having a hole pierced through near the rim; strings had been passed through the holes to tie the roundels together in sets of eight or more. Such clay roundels are found at all early levels in the Flood pit at Ur, but their use cannot be determined.

Museum Object Number: 31-16-604

Image Number: 191429

Image Number: 191428

Image Number: 191443

Image Number: 191449

Museum Object Number: 31-16-643

Image Number: 191449

As a result of the season’s work we can draw up the following sequence, which accounts for nearly every type of pottery as yet known in south Mesopotamia:

- The First Dynasty of Ur, about 3100 B. C.

- The Royal Cemetery, about 3500 to 3200 B. C.

- The period with “reserved slip ware.”

- The period with the tall clay footed goblet.

- The lower seal-impression period, about 3750 B. C. (?).

- The period of pink pottery with red bands.

- The Jemdet Nasr Period.

- The period of plain red pottery.

- The al-`Ubaid period, phases n and m, which are post-Flood.

- The Flood.

- The al-‘ Ubaid period, phase 1.

Between (2) and (3) there is a gap, during which the culture seems to be closely akin to that of (2). Stages (5) and (6) may well be synchronous. Stage (8) is one of transition, and at present seems to pass insensibly out of (9) and into (7), but does have a short independent existence.

In order to avoid a confusion already prevalent I must refer to the discovery of a diluvial deposit at Kish, which also has been held to represent the Flood of Sumerian legend. This deposit, about eighteen inches thick, is certainly not the same as that at Ur described in this and my last reports. It is dated by the discoverers between 3400 and 3200 B. c., and runs unbroken over the cemetery, which they date at 3400 to 4000 B. C.4 The cemeteries at Kish and at Ur are shown by their contents to be of much the same date, although that of Kish may well go back somewhat earlier for its beginning (so as to cover the gap between my stages (2) and (3) above); Langdon’s positive dating appears to me to be much too early. The main point is that the Kish flood deposit comes on the top of a cemetery whose latest date cannot be far removed from the latest date of that at Ur; below the Kish cemetery comes a level containing masses of fragments of the tall goblet type of vase (my stage 4), together with plain red pottery, and below this again comes the Jemdet Nasr level. In the particular spot chosen for deep excavation at Kish, Jemdet Nasr occupies the lowest stratum resting on virgin soil, and there is no vestige of al-` Ubaid occupation. At Ur, the Flood level comes under al-‘ Ubaid II, and is therefore separated from the Kish flood by eight different cultural strata, which in time must mean a very long interval indeed. Actually there is in the same pit at Ur between levels 14 and 15.50 metres above sea-level a waterlaid deposit filling all the space between the walls; it is composed of minute strata averaging less than a centimetre in thickness, and must have resulted from continual flooding of the same area: stratigraphically this might conceivably represent the same flood as has left its traces at Kish, and if so the time-gap between it and the great flood deposit between levels 1 and 4.50 metres above sea-level is even more obvious, though not more real, than if we simply contrast the two sites. It must be remembered that floods are common things in Mesopotamia; if we are to connect extant traces of a flood with that described in the legends, we must look for something (a) so vastly surpassing the normal that the memory of it endured through centuries, and (6) so much earlier than any written record of it that its story had become miraculous and the gulf had to be bridged by dynasties of fabulous longevity, while (c) its social effect must have been such that for the later historian it marked an epoch. The conditions (a) and (b) are surely better met by the magnitude and position of the Ur deposit. As regards the condition (c) Lang-don argues that the Kish flood does close an epoch, on the ground that the cemetery below the deposit “contains pottery types almost totally different from those above the Flood stratum.” This is of course true of the part of the site excavated by Watelin, but breaks of continuity in archeological stratification are quite normal, as every digger knows, and Langdon’s deduction from this negative evidence disregards everything that we know about early Sumerian history. The Kish graves are admittedly homogeneous on the whole with the Ur graves; the upper strata missing at Kish are present at Ur, and, so far from the culture represented by the graves stopping short with the end of the cemetery period, it is carried on with remarkable continuity into the First Dynasty of Ur, which on Langdon’s own dating is post-Flood. The Sumerian annalists believed that between the flood and the First Dynasty of Ur there came two very long dynasties, of Kish and of Erech. To make the Flood occur shortly before 3000 B. c. is to reject a tradition which a priori should have some foundation in fact; and to assume that, occurring then, it altered the course of civilization is absurd, because there is no such alteration. If the Ur deposit marks the flood of Sumerian legend the introduction soon afterwards of the Jemdet Nasr pottery, almost certainly a foreign fabric, may be taken to satisfy the condition.

1 Described in the Antiquaries Journal for October, 1929.↪

2 The character of the stratum is given as it exists at the point of the section; though it may run consistently over the whole area it is not likely that over the whole area the same sort of rubbish would have gone to its composition, and a stratum red in one place may well be grey or white in another and yet be the same stratum.↪

3 Specimens of the sand and clay from the two deposits left by the Flood were submitted to the Petrographical Department of the Geological Survey, Jermyn Street, London, for microscopic analysis. Dr. H. H. Thomas s report was as follows:

“The soil specimens and silts have been examined and I find Specimen Z is a fine grained. closely laminated silt, the laminæ showing definite current-bedding and grading of particles. On a cross-section certain laminæ may be seen to wedge out in a manner that can only be accounted for by the action of gentle currents. In a distance of two inches the laminæ may tail off from a thickness of one or two millimetres to the merest 61m. The average thickness of the laminæ is something less than a millimetre. The silt has a definite parting parallel to the surfaces of the lamina., which are seen to be covered with the minutest scales of detrital mica.

“In constitution the material is mainly fine angular quartz, with much finely divided mica, fairly abundant green hornblende, with some augite and magnetite. The particles are somewhat variable in size, as would be suggested by the lamination of the sediment. They range up to 0.1 mm. hut mostly they have much smaller dimensions.

“Sample X has practically the same constitution and texture as Z except for the absence of lamination.

“Sample Y is of a fine clay material with particles mainly under 0.01 mm. and highly micaceous. it is quite possibly water deposited, for it would be difficult to account for it in any other way.

“The absence of lamellation might suggest wind-blown dust, but there is a complete absence of any larger or rounded particles which usually occur in æolian deposits.

“The material of X and Y appears to be derived in part from a series of hornblendic and augitic igneous rocks.”

Samples Z and Y are from the pit excavated this year, X from the shaft sunk in 1928-29.

↪

4 S.Langdon, Excavations at Kish, 1928-29, in Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1930, page 601; quoting M. Watelin.↪