A number of important pieces of Chinese sculpture accumulated during the last two years deserve special mention, though at this time no attempt at an extended treatment can be made. They are published here that they may be allowed to speak for themselves. At a later time we may hope to follow this publication with more adequate comments on each piece.

Bronze Statue of Kwanyin

Museum Object Number: C400

Image Number: 1156

There are few works even of the best period of Chinese sculpture that have so much charm as this precious little Divinity in Bronze. Her height from the sole of her foot to the top of her tall headdress is 28 inches. The figure is nearly solid, though from the shoulders down there is a narrow cavity where a slender core had been set in the casting. The entire surface of the bronze was covered with gold, now nearly all removed except on the face and neck and parts of the headdress.

The posture of the figure, evenly balanced on both feet, firmly planted on the ground and rising trunklike to support the well poised head with its sensitive features, so mobile yet so still, so full of wisdom, of tenderness, compassion and a sense of inward peace, yet unmarked by a trace of human emotion, has a wonderful effect of outward dignity and inward grace.

In her left hand the goddess holds a pomegranate in front of her breast. Her right, with tapering fingers, is raised towards the necklace as though arrested in the act of telling her beads. Her robes, folded freely about her, describe graceful lines that veil but do not extinguish the human form within. That frail and sensitive form becomes the vibrant core of the image, with its outward strength and dignity, its calm assurance, its harmony of line and direct simplicity. The human form indeed is not portrayed but it is nevertheless revealed, for it becomes the living thought within, about which the elements compose themselves like the vestments of a spirit.

The image was found in 1918 in the bottom of a river, according to our information, “near the Aipao village which was the ancient seat of the Tsien-Ning temple” The village mentioned is a suburb of Liao-Yang, south of Mukden, Manchuria.

As to the date of its execution it would seem at first sight as if we could hardly do otherwise than assign it to the Tang Dynasty, even to the very beginning of that period—the early years of the seventh century, yet it is necessary to be cautious. There are some indications that the date may be several centuries later, but to whatever period it may belong it represents the highest refinement of Chinese Art.

The Buddha in Lacquer

Museum Object Number: C405A

Image Number: 1425

The technical process of this sculpture is rarely found in surviving examples, though it was known in China as early as the T’ang Period to which this specimen belongs. It consists of lacquer laid upon a cloth of coarse texture. The entire figure is hollow and the fabrication is little more than an inch in thickness. The position of the figure which is life size is very unusual and interesting. It is moreover a striking composition in which a simple idea simply expressed comes out with force and eloquence. It will be seen that the drapery is treated with greater freedom than in the stone, wood and clay figures illustrated in these pages, a treatment in keeping with the semifluid nature of the medium in which the artist worked which readily adapted itself to the natural folds of the textile fabric on which it was laid.

The provenance is unknown. It is said to come from an ancient monastery in North China. Accompanying it are a set of old writings that were found in the interior of the statue and which have not yet been translated.

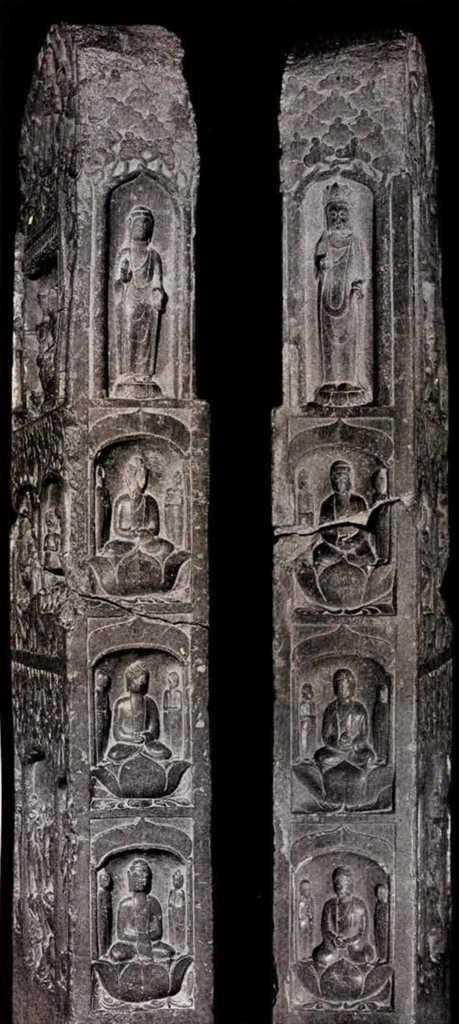

A Memorial Stela

This monument was recently found on the site of the ancient Buddhist temple of Tien-lung-san in the Province of Shensi and northeast of Sian-fu. On the obverse are seen deep niches of architectural design filled with Buddhist figures. At the very top is a little shrine guarded by two descending dragons supported below by angels. On the reverse are other niches with more figures. Here the upper group is enclosed in an arbour with little figures emerging from the blossoms of the trees. On the two edges, figures in bold relief repose in niches and on lotus flowers. On the obverse below is an inscription of which a translation has been furnished to the Museum by Mr. Sasaki Y. Shigetsu. A brief paraphrase of this translation is given below. The date given is in the Sixth Century.

Museum Object Number: C429

Image Number: 1362

Phenomena spring from the inmost consciousness. Phenomena and consciousness together make up the universe. . . . .

Chung San plucked the weeds in Lung Hai and helped the people in their peril. Now, mounted in a vermilion cart with a blue canopy he, with his mysterious voice, greets the generations. . . . He emaciated himself to enlighten the people and illuminate his own soul. For the sake of Buddha he has done all this. . . . Therefore his relations have set up this stone with reverence, this rare stone that they brought from a distance. On Buddha’s birthday they set it up in the sixth year of Wu Ping of the Chi Dynasty. It is eight chih tall and carved with many figures and dragon trees by the heavenly skill of the artist.

The sacred images face the south . . . and it leads the way to Nirvana, like a stairway hung in the sky. Pray that you may not die till you have seen it. . . . Pray for long life, to live as long as stone or metal lives in the earth, as long as the glory of the sun and the moon in the sky.

We offer our reverence to His Majesty the Emperor: we offer it from our hearts that are purified.

We pray on behalf of his hundred officers that the eight misfortunes may be removed and that the three adversities may be averted. . . .

Truth is neither new nor old. It is identified with all things as if words were things.

A Pair of Stone Lions

These vigorous sculptures attributed to the fifth century, are probably not surpassed by any surviving works of the period. Moreover they illustrate in a conspicuous degree some of the qualities that belong to the earlier periods of Chinese sculpture and that are not so marked in the later periods. These qualities are solidity and strength. The lines are cruder but not less expressive. The modelling is bolder and less finished but even more forceful. The delicate surfaces of the fine sculptures of the T’ang, for example, are absent and details that would receive some recognition on the part of T’ ang sculptors are ignored entirely by the earlier artists. The very erect position, the vertical pillarlike front paws, the massive ferocity all are qualities that mark an early stage in the history of Chinese sculpture.

Museum Object Number: C433

Image Numbers: 1333, 1334

Museum Object Number: C432

Image Numbers: 1329 – 1332

These lions were placed in the gateway of some temple, now unknown. Their duty was to guard the shrine from all enmity and evil. They therefore embodied the conceptions of power and endurance. Eternal vigilance was their portion. It must be admitted that the fifth century sculptor expressed these conceptions with much success. His chief motive evidently was stability combined with energy. All the rest that he sought to convey follows quite naturally in these very impressive sculptures. It is an art that contains great promise and that already records a great achievement. Though the original place of these stone lions is not known, it is reported that they were found isolated at Chen Chow in Honan Province half buried in the earth. No remains of a temple were discovered.

A Wooden Statue of Kwanyin

Wooden statues of Kwanyin in an attitude similar to this are not infrequently seen in public and private collections today. This example is carved from a single piece of wood except the hands that are joined at the wrists. The natural surface of the wood is nowhere exposed, the whole figure being finished in gesso overlaid with pigments and gold leaf. The seat on which the figure rested is missing; otherwise nothing has been lost. In the back there is a large and deep recess evidently intended for a reliquary. A single lock of hair is looped across each ear just above the elongated lobe, a feature that this statue has in common with the bronze figure on Plate IV.

Similar wooden figures have been assigned to the twelfth century and to the Southern Sung, a period that witnessed a high development in sculpture. Whatever period it may be referred to, and a definite decision is not yet possible, there is no question about the skill of the artist or about the spirit of the time in which he lived. True, it strikes a different note from the other sculptures here illustrated but with all that departure, the great traditions of the previous periods of sculpture have not been lost.

Museum Object Number: C408A

Image Number: 1423

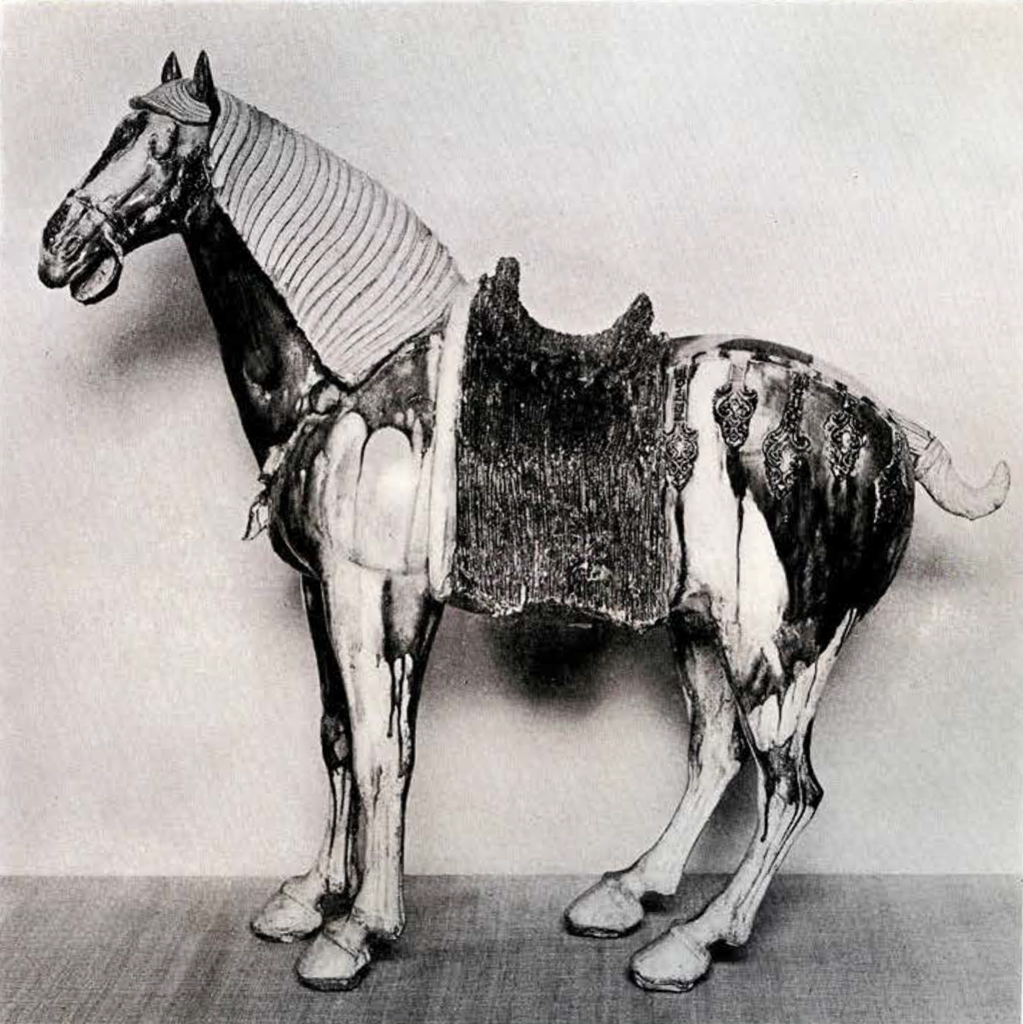

Pottery Horse

Such figures as this of which the Museum now possesses three specimens are sometimes found in tombs of the period of the Tang Dynasty (618-906). The Chinese horse of the period is evidently of a type not otherwise unknown though presenting some easily noted characteristics of his own. It is presumed that the horse was placed in the tomb to serve his master according to a belief in some form of service after death. It is made of a fine light cream coloured clay, quite soft. The glaze on this as on other figures shown are green, yellow, brown and cream.

Museum Object Number: C409

Pottery Camel

Besides the horse, the camel was assigned in the form of a pottery image to serve his master in the tomb. Here he has his pack in place ready for a journey. The glaze on all of these figures is green yellow, brown and cream.

Museum Object Number: C410

Pottery Figure of a Warrior

The furnishings of the tomb of a man of station and consequence during the great Tang period in China often included the figure of a warrior or a guardian spirit in armour, fierce and vigilant, trampling a monster under his feet. It is noticeable that he never carries any weapons unless his teeth and his doubled right fist might be so regarded. The idea appears to be that the personal appearance of the guardian should be sufficient to repel all hostile influences.

Museum Object Number: C401

Image Number: 1601

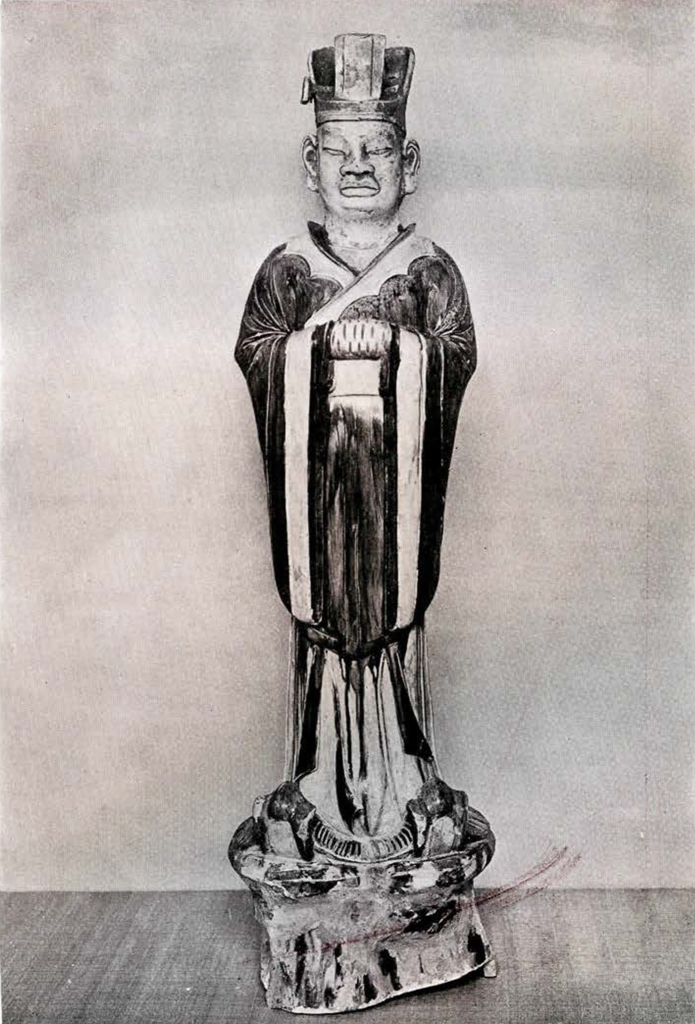

An Official of the Dead

The dead man was not to be deprived of the helpers or councillors or ministers that had made life more agreeable and less troublesome for him. In this figure is seen such an official of high rank, haughty and selfpossessed, quite capable of rendering the sagest counsel. In this figure as well as the last and the next, the garments only are glazed. The face and neck and hands of each figure are without glaze.

Museum Object Number: C403

Another Official of the Dead

This figure evidently represents one of lower rank than the last but still a person of importance. The pride and complacency of the other are replaced by a certain measure of diffidence. That the artist who made the figures consciously expressed these differences there can be no doubt. The difference in rank is also expressed in the costume. The horse, the camel and these three figures were found in one tomb and form a group by themselves.

Museum Object Number: C402

Group of Clay Figurines

These charming and dainty little figures apparently represent a great lady watching a performance by a pair of dancers who are accompanied in their movements by two wind instruments and one stringed instrument, played by three lady musicians. The illustration does not do justice to the group that was found in a lady’s tomb at Honan Fu. No part of the figures is glazed but the clay is covered with paint in various colours And also with traces of gold in the robes of the great lady.

Museum Object Numbers: C426 / C422 / C421 / C424 / C423 / C425

Image Number: 1562

Museum Object Number: C426

Museum Object Numbers: C421 / C422

Image Numbers: 1543, 1552

Museum Object Numbers: C423 / C424 / C425

Image Numbers: 1560

Museum Object Numbers: C429