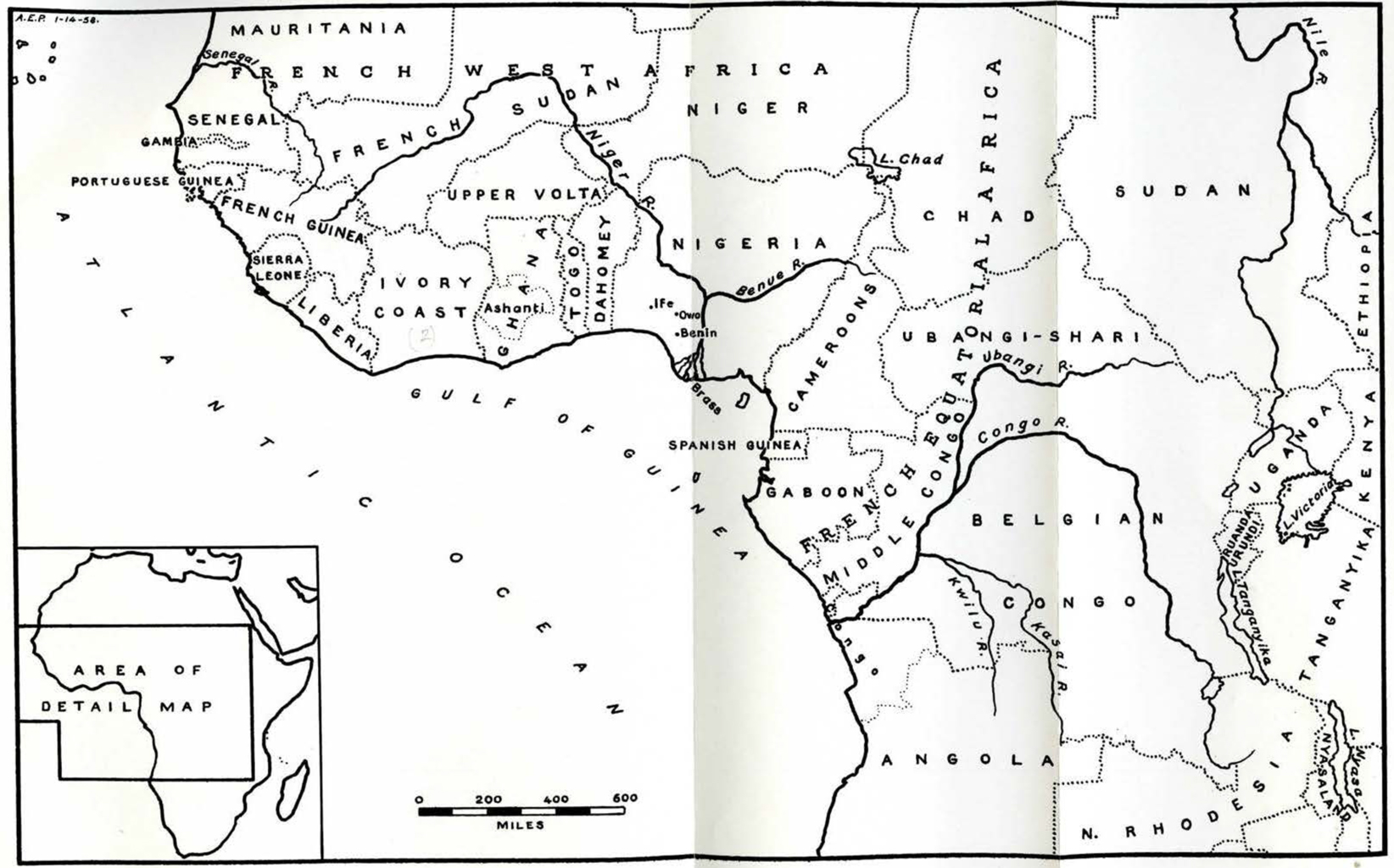

The new African Gallery has been designed to exhibit, simply and honestly, a selection of sculptures from our permanent collections. Proudly we present them as works of art; where possible they are arranged in tribal groups for convenience and comparative study. They are labeled briefly and clearly. Here are the materials from which our visitors may form a just view of the special characteristics and merits of Negro art.

For more than half a century our Museum has been enriched by accessions of African sculpture, mainly by purchase and partly by gifts, to the end that our permanent collections are the largest and most varied in style in America.

The following descriptive notes are not to be construed as an attempt at a catalogue of the exhibition; the serious student may have access to fully documented formal catalogues should he apply to the Museum staff. In Dr. Coon’s introduction he has given us the anthropological and ethnographical background of the people who produced this art, working within the framework of their tribal traditions. Here in this book, with their photographs, are small synopses of what we know of these sculptures, and what we guess. We all have conscious, and sometimes unconscious, difficulty in understanding such works of art; the philosophical barrier that lies in the way of full appreciation is almost too difficult to hurdle. Many writers have tried to explain the magico-religious significance, the strength and directness of African art; few have succeeded. Perhaps these notes are mere hints and suggestions, but we hope that they may sometimes be stimulating as well as factual.

It is important to forget the easy generalizations of those who see striking similarities in the work of modern and African artists because they are both free from the restrictive effects of naturalism. The resemblances commonly found between modern and primitive art are essentially superficial; modern art carries on the European romantic tradition; tribal art is predominantly classical, the artist accepting and expressing the traditions of his own tribe and never seeking to escape from them. This is no shackle on the genius of the primitive artist; it is the same sort of challenge as was the naturalistic canon for the sculptors of Greece and the religious convention for the artists of Renaissance Italy.

Image Number: 62668

Image Number: 62669

Image Number: 62671

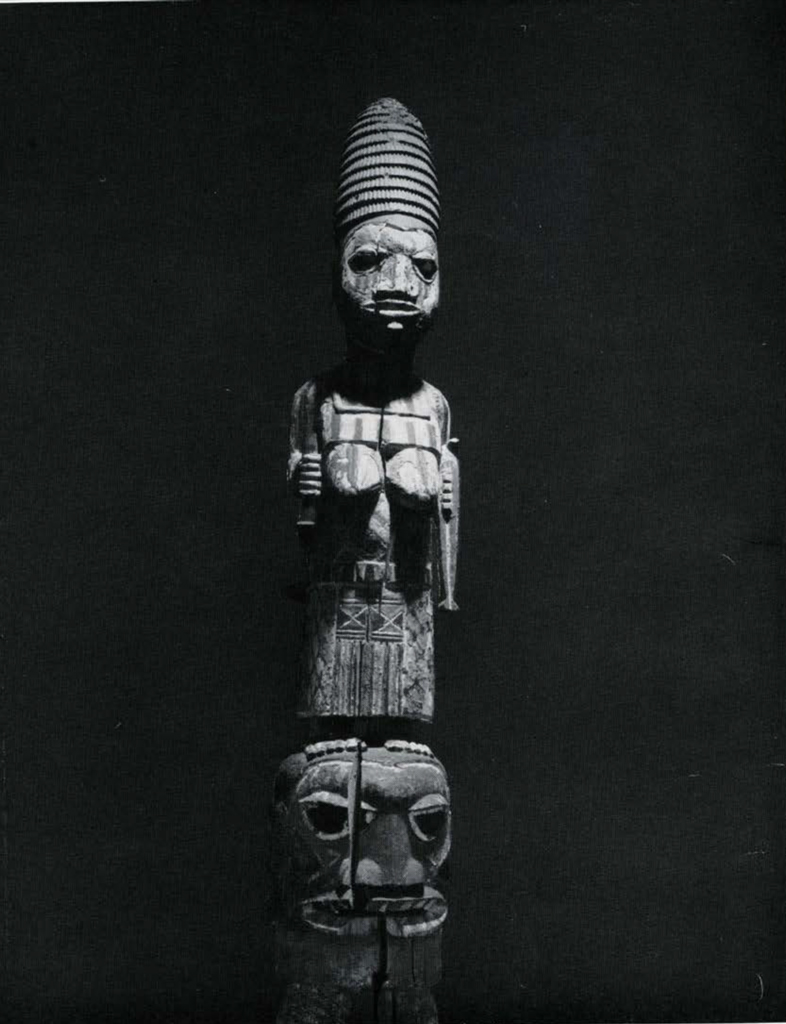

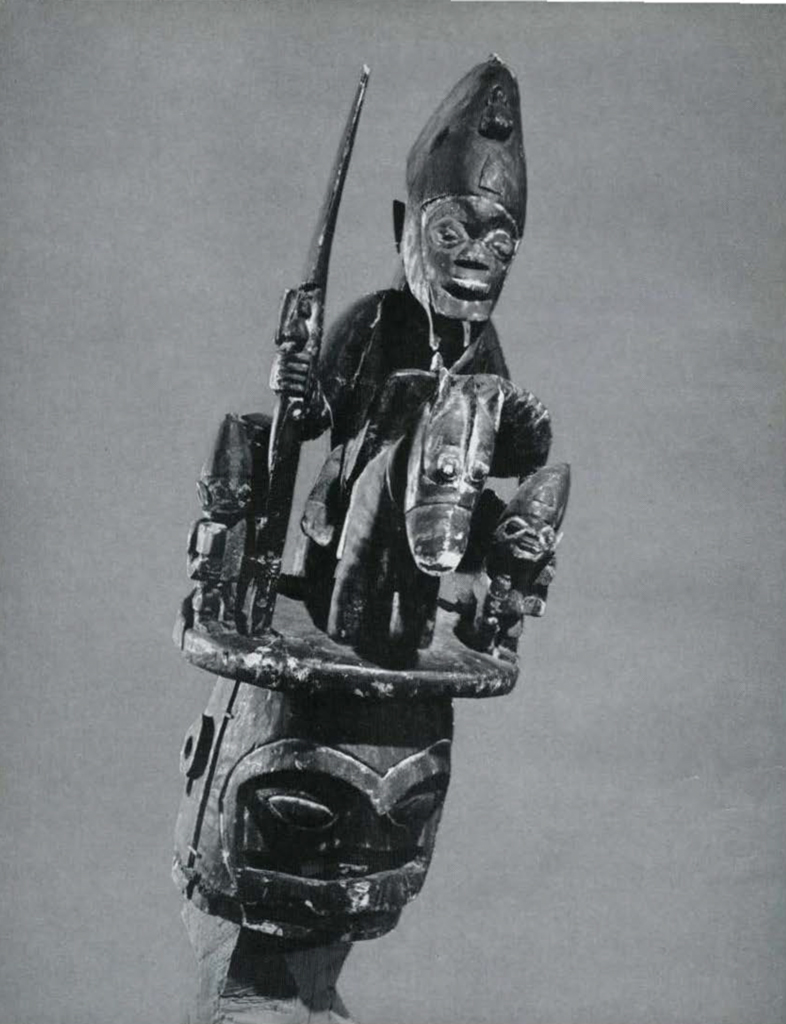

THREE GREAT HELMET MASKS FROM THE YORUBA OF NIGERIA

In the remote northeastern part of Yorubaland, chiefly in the Oshogbo and Ekiti districts, is found one of Africa’s most extraordinary and interesting cults. It goes by various names in different parts of the area, the best known being Epa and Elefon. For the devotees of the cult in each village Epa is the chief object of worship, the purpose being to promote increase of all kinds, not only for the cult group but for the whole community. According to one story, Epa was a great carver who was deified after his death, but this may be a latter-day rationalization intended to be within the comprehension of European inquirers. In most villages there is a great Epa festival every two years (with a lesser celebration in the off-year), normally held at the time of the Spring sowing in March. In this the young men vie with each other to have the most striking and elaborate masks, and perform twirling dances, finally competing in leaping onto a mound three feet high without dropping the heavy and unmanageable masks.

The grotesque Hallowe’en head which forms the mask proper is overshadowed, in a museum, by the monumentally carved and often rather naturalistic superstructure; but in the movement of the dance the mask itself-usually two-faced-comes into its own and dominates the scene.

Here are three, representing classical subjects of the Epa cult: Olomeye, the Mother of Children; Ologun or Jagun-Jagun, the Warrior, a man on horseback with attendant figures. These masks and those in the British Museum in London are the only fine examples of Epa masks to be found outside of Nigeria.

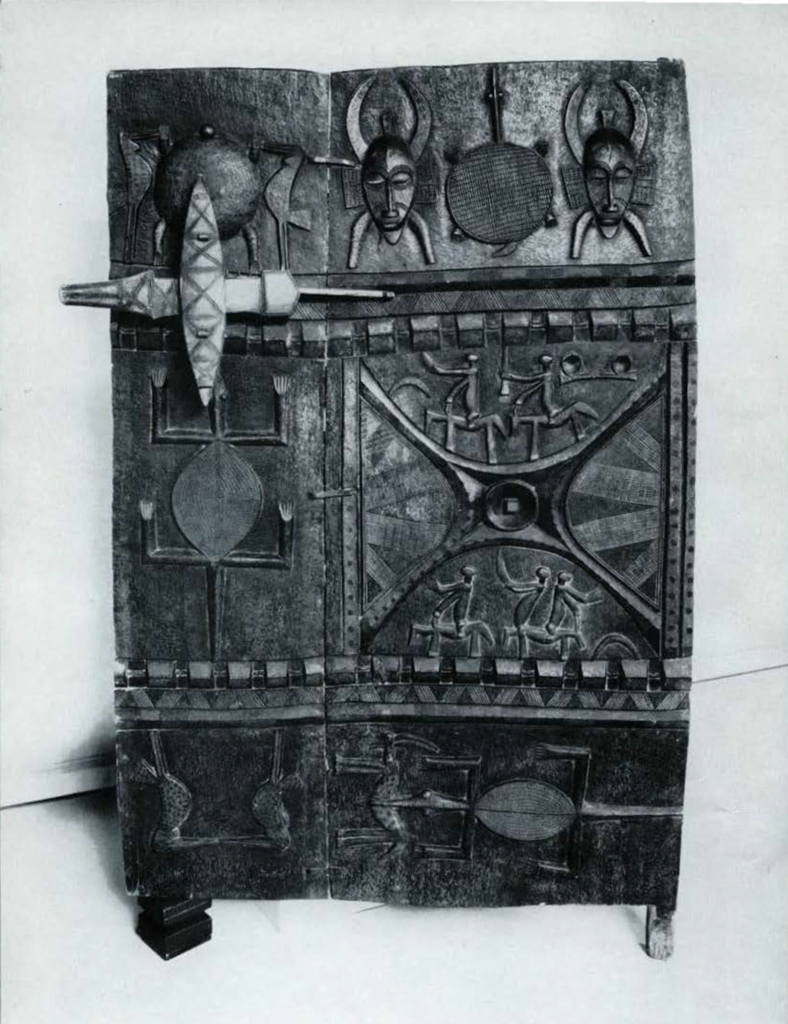

A DOOR, TWO MASKS, A LOCK, AND AN EQUESTRIAN FIGURE FROM THE SENUFO OF THE IVORY COAST

Only in our Museum could such a superior group of objects from the Senufo be arranged in America. The famous door, probably carved for a secret society’s house, has been exhibited widely throughout the United States and the small masks with “legs” are almost replicas of those carved in the upper right hand panel of the door.

Stylized horsemen are frequent subjects of the Senufo sculptor. Here are three versions: those carved in the center panel of the door, the small equestrian figure surmounting the Arab-type lock, and a horse and rider alone. It is said that the riders represent notables from another kingdom, horses being rare in the Senufo country and kept chiefly for display; or perhaps they are mules, not horses.

Image Number: 62673

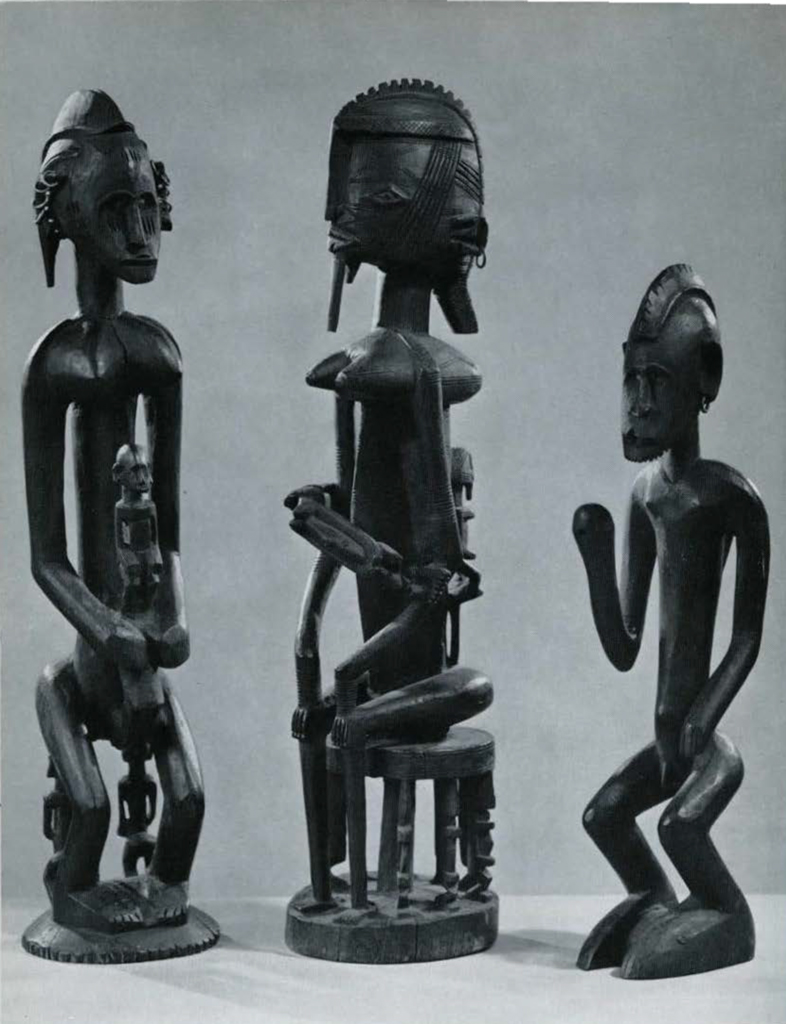

THREE DOGON FIGURES FROM THE FRENCH SUDAN

Seated women, hung about with small human figures and sculptured by some early “Cubist” of the Dogon tribe, are sometimes said to be associated with a cult devoted to the souls of dead pregnant women. They are among the most stylized of all African carvings. These two women along with their male companion are among the best known African sculptures in America and have often been exhibited as well as illustrated in many books and catalogues.

TWO ANTELOPE HEADDRESSES FROM THE BAMBARA

Many years ago, when the world was young, among the Bambara people of the Sudan, the savannah country, there lived a legendary being, half-human and half-snake, called Chi Wara, who taught men to cultivate the earth. When the earth grew abundant, men lost their regard for the Chi Wara and treated the grain he had produced for them with disrespect. Outraged at the sacrilege, rejected and sorrowful, Chi Wara dug his own grave with his head and neck, his head like a pointed hoe, his neck curved and dilated Like its handle, and buried himself.

Men, having lost him forever, remembered then the magic he had made for them, how he had made the grass and the grains to grow and how all the land was fertile because Chi Wara cultivated it. They made masks and headdresses to commemorate him, and every year danced at seed-sowing time in his honor. The members of the agricultural societies, called Chi Wara too, wear scarifications (Chi Wara Ti), made in imitation of scarifications on Chi Wara’s face.

Here, on our Chi Wara headdress masks we see the Ti – two vertical lines under the nose and slanting parallel Lines beneath the eyes. Multi- plying the resemblance to Chi Wara, thought the Bambara, would increase the zeal for work, increase the fertility of the soil, and that of the tribe itself. Solange de Ganay, a disciple of the late great Professor Dr. Marcel Griaule of the Sorbonne, collected these data on the Sixth Griaule Expedition in 1946-1947.

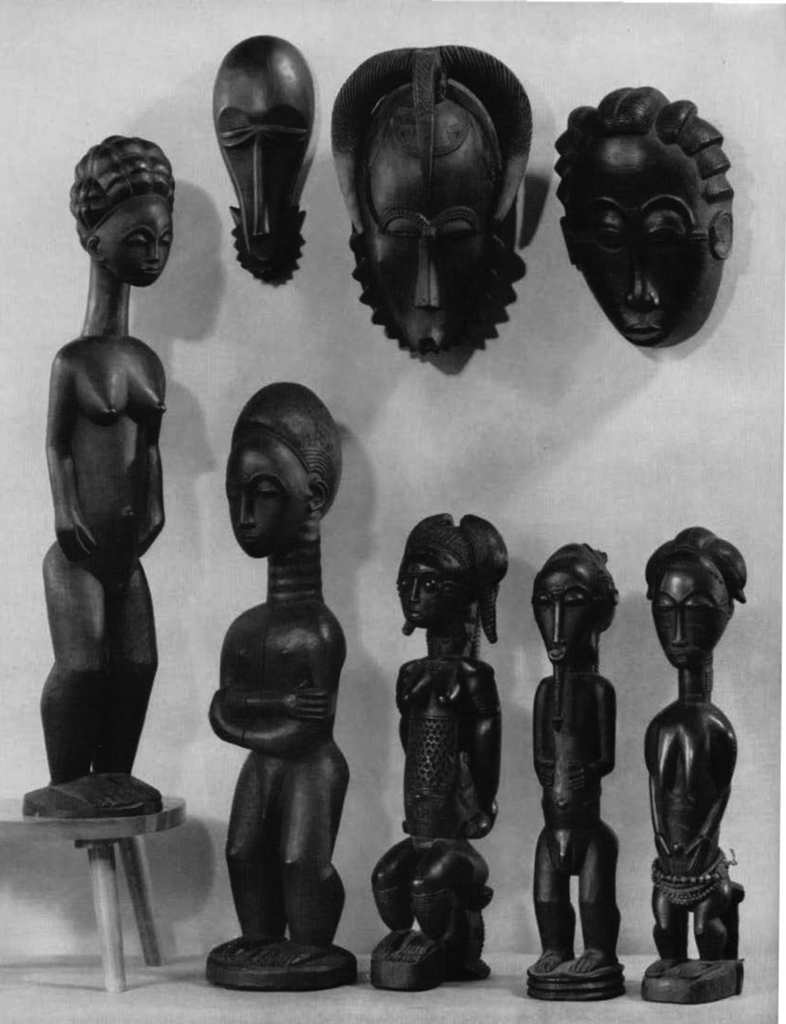

BAULE FIGURES AND MASKS

The cult for uncritical evaluation of Negro sculpture, christened “négrèrie” by William Fagg of the British Museum, has often been fed by false enthusiasm for these most easily liked figures and masks of the Baule people of the Ivory Coast. Perhaps because these naturalistic little figures, these smooth and pretty masks, are closest to our own aesthetic traditions, we are apt to find them our favorites when first we awaken to interest in these, to us, new art forms.

Literally thousands of casts have been made and sold of 29-12-68 and 29-12-138; they fit well into modern interiors, and are often favored by avant-garde decorators for their chic. Labelled “ancestor figures” and “gods,” “spirit masks” and the like, their purchasers congratulate themselves on their breadth of aesthetic vision.

In truth, there are many excellent sculptors among the Baule, and such figures as 29-12-69 and 29-12-72, such masks as AF 5369 and 29-12-133 are among the finest in our own collections. But because the Baule have long had close association with the French Colonial Administration and the European traders, and because they are among the few tribes producing art as much for secular as for religious purposes, there is considerable repetition in their output, the virtuosity of which must make up for its lack of originality.

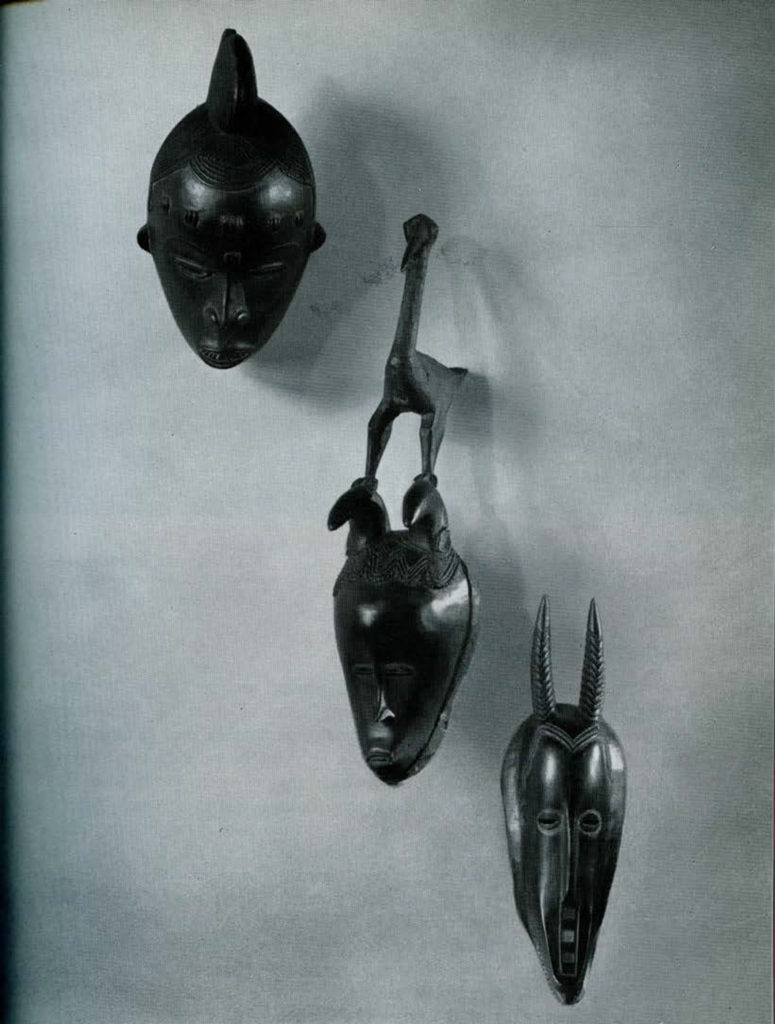

THREE MASKS FROM THE CURO OF THE IVORY COAST

Masks and heddle pulleys from the Guro are plentiful in the museums of the world and have been reproduced with great virtuosity by the carvers of this tribe, even though, after association with Europeans, the Guro, like the Baule, have indulged in considerable copying and duplication.

However, our museum takes great pride in the possession of this fine Guro mask surmounted by an ibis-like bird, one of our best known pieces. The simpler, frontal dance mask shows the typical Guro coiffure. The horned antelope mask with human nose and classical coiffure is an example of the dance mask used in ceremonies of the Zamle secret society, one of the most important fertility cults of this tribe.

Image Number: 62579

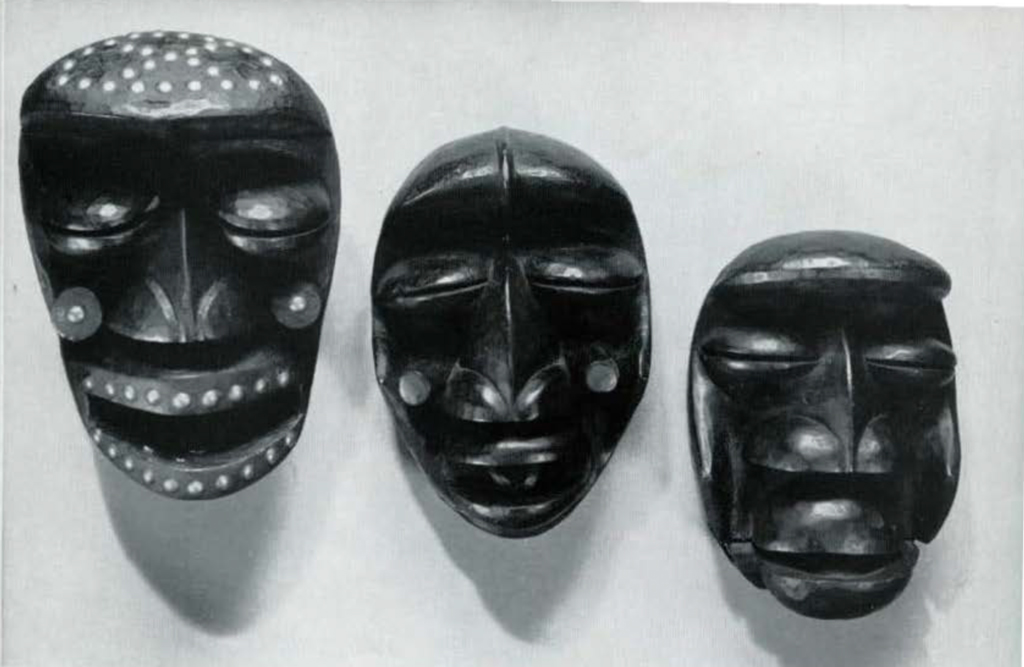

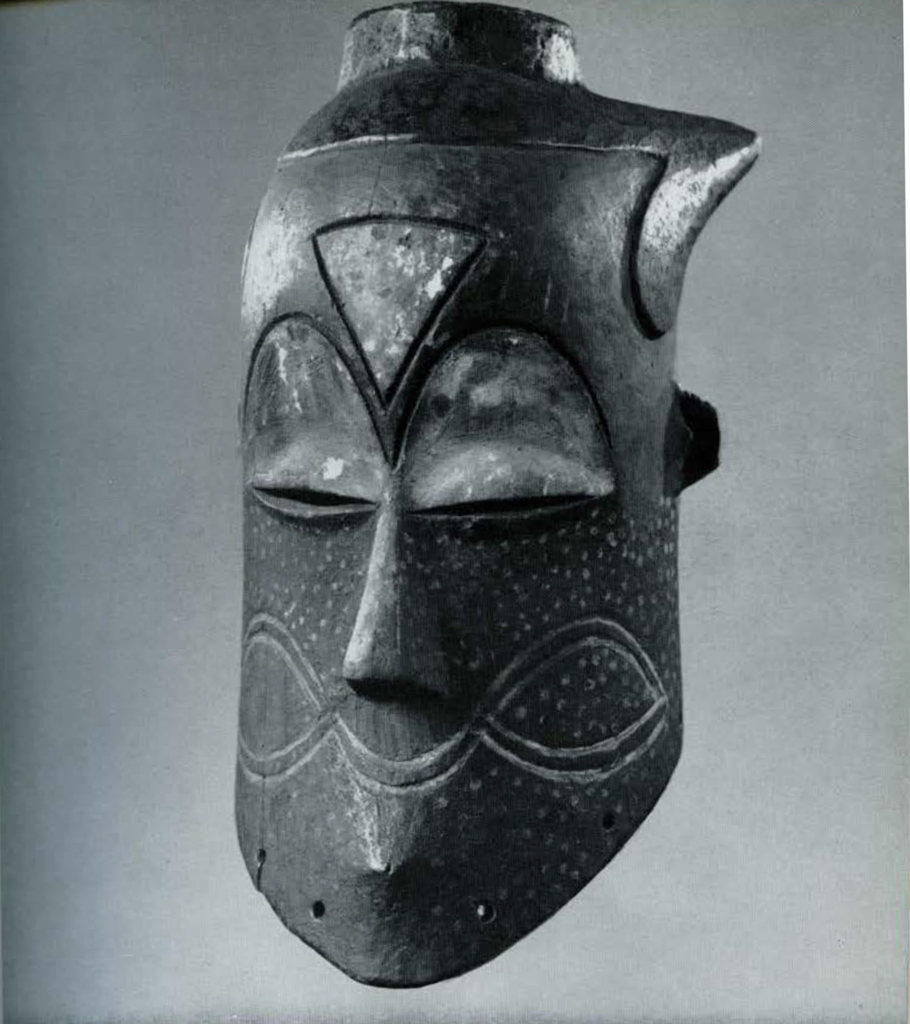

THREE MASKS FROM THE NGERE

The Dan-Ngere tribes occupy a widespread area in Liberia, the Ivory Coast, and the southern Sudan. Among some of them the Poro secret society is a dominant feature of the social organization, and in these cases art is largely under its auspices. There is a duality or dichotomy among them, most evident in their masks, which enables us to group them into those of the Dan and those of the Ngere tradition. It is extremely difficult because of the interdependence and mutual influence of neighboring tribes exactly to attribute the masks to the various subtribes, but Dan masks are usually smooth and restrained, in contrast to the exaggeratedly (one might almost say beautifully) ugly and more powerful Ngere masks. This group of Ngere masks is almost cubistic in feeling. Imagine them complete with their costumes of swirling bright-colored cloths, and worn by the Poro society dancers for whom they were created. These “warthog” masks, often with movable mandibles, are used in dances to the big drums after the circumcision rites of the boys of the tribe.

Image Number: 62676

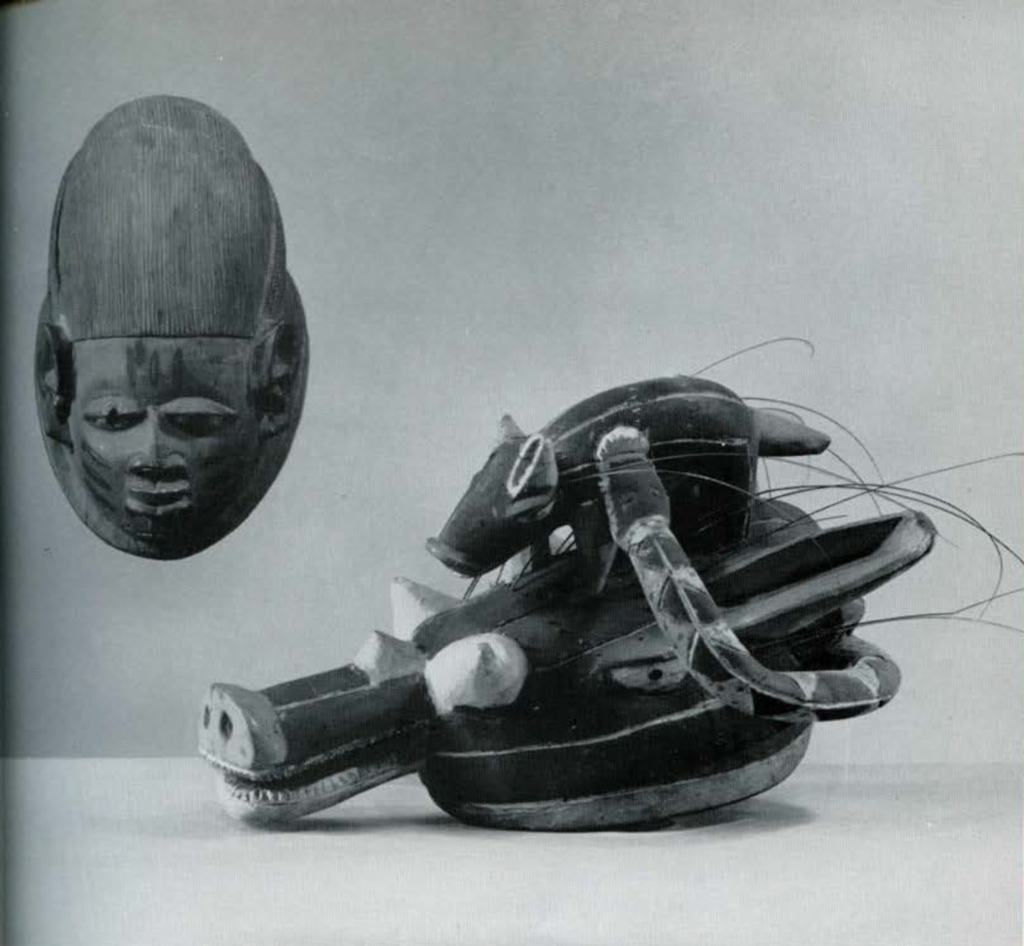

A BOVINE MASK FROM THE BAULE OF THE IVORY COAST

So-called cow masks-they may be buffaloes or oxen or any bovine animal-are common among the Baule, and stylized bovine beads like this mask are found in all sizes, whether as tops of heddle pulleys, gong strikers, spoon handles or, as here, life-sized. This is a dance mask and to be fully appreciated must be imagined in movement, covering the head of a man clothed in a great cloak of hairy grass, the dancer weaving a magic spell to avert misfortune and to keep evil spirits from his dead or living tribesmen.

Image Number: 62677

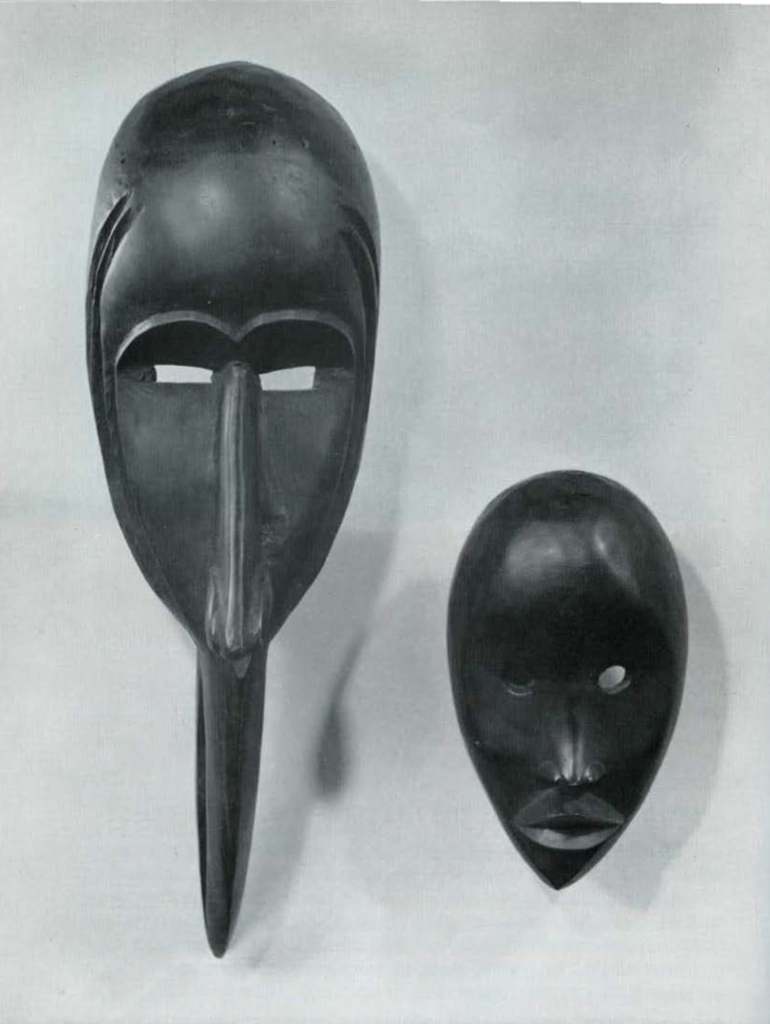

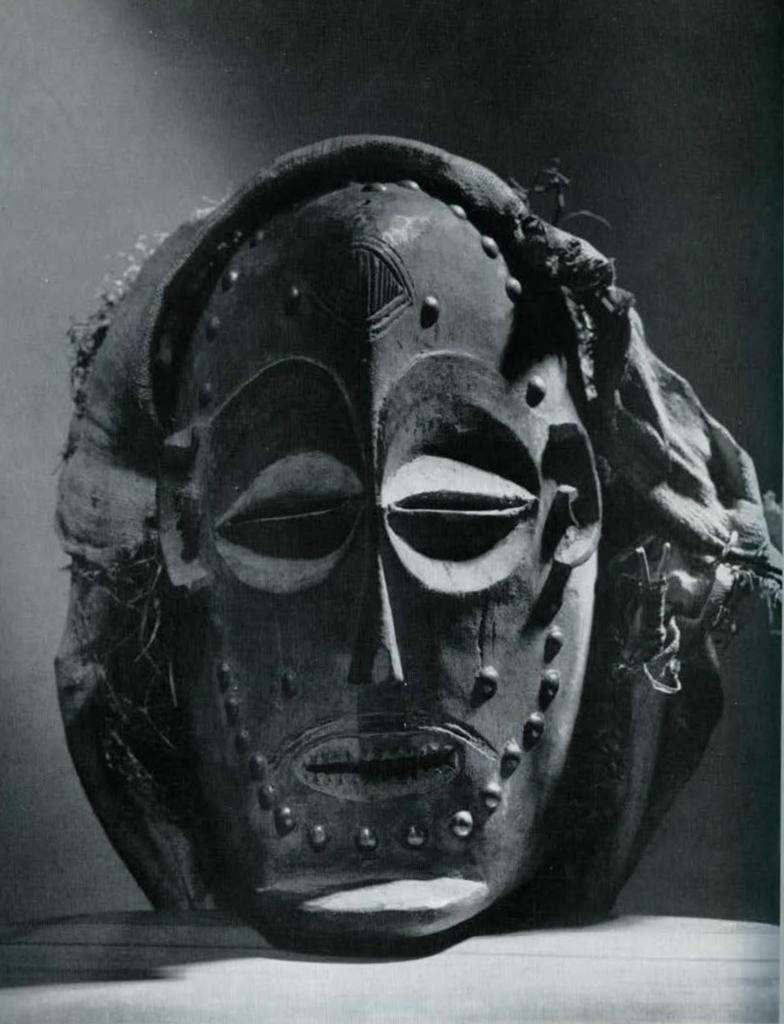

TWO DAN MASKS

From the congeries of many small tribes called for convenience Dan-Ngere, in the Ivory Coast and Liberia, come these most typically Dan masks. The round-eyed, full-lipped mask with its polished black patina is in a style often seen in African art collections, a classical Dan mask, but the mask with the long curved bird-beak for a nose is of a rarer type carved by its anonymous artist with consummate skill and feeling.

A HELMET MASK AND A CULT OBJECT FROM THE MENDE OF SIERRA LEONE

In Sierra Leone, in the Mende tribe, the women are strongly organized into a secret society known as the Bundu (sometimes called the Sande). Here only, in all West Africa, do the masks belong to the women. Such helmet masks as this blackened cylindrical carving, decorated with the spiral shells of giant snails, are worn by the women leaders of the secret society who are appointed to train the young girls in the bush for their duties as adult women of the tribe, and for membership in the powerful Bundu. When the initiation period-which may last for some months-is finished, the girls return to their village for what might be called graduation ceremonies and dances, led by their instructor wearing such light wood masks, carved from the soft wood of the bombax tree, and wrapped completely in a great hairy cloak made of vegetable fibre dyed black.

The shallow wooden bowl from which rises the blackened torso of a young woman is probably a ceremonial cult object from the same secret society, perhaps for use in divination.

Image Number: 62678

THREE BRONZE HEADS WITH TUSKS FROM BENIN, NIGERIA

From the great British dealer and connoisseur of tribal art, the late W. O. Oldman, came, in 1912, these three splendid heads, supporting carved elephant tusks. They were cast of bronze by the cire perdue process and brought from Benin in 1897, after the time of the British Punitive Expedition.

The great medieval empire of the Bini, with its capital at Benin, had passed its apogee by the end of the seventeenth century, and for two centuries its civilization had decayed. The Bini country had been depopulated by civil wars and raids by neighboring tribes, and decadence in art seems to have followed decay of the nation.

It is the court art (rather than the tribal art) of Benin that still survives in the bronze castings and ivory carvings, an art originally borrowed from the Yoruba and increasingly devoted to maintaining the tottering pomp and prestige of the Obas or kings. The bronze casters, who lived in a special street of their own near the Oba’s palace, were forbidden on pain of death to work for anyone but the Oba; hence their works were nearly all found within the mud walls of the Royal Palace.

Image Number: 62593

GELEDE AND EGUNGUN MASKS FROM THE YORUBA OF NIGERIA

Caplike masks like these are worn flat on top of the head by members of the Gelede and Egungun societies among the Yoruba. One purpose of the societies is benevolent and advisory; they in every way work for their members and through their members to benefit the tribe, but above all they are devoted to increase, with the help of the spirits of the dead.

For funeral dances for dead members of the Gelede or Egungun, and at the annual festivals, the masks are worn with the dancers’ best and brightest scarves and cloths. (Gelede masks are always carved in pairs for funerals.) Death in Africa is a matter of congratulation as well as a time to make the departed spirit happy.

The Gelede society is found only in the western part of Yorubaland; the Egungun is found among all Yoruba communities and also among the Bini to the east and the Fon of Dahomey to the west. In general, Egungun masks (as here) are more fanciful and elaborate, while Gelede masks have a flattened, receding face which is foreshortened when seen from the front.

Image Number: 62597

TWO BRASS ROOSTERS FROM BENIN

In the Oba’s palace, the royal altars, long, sunbaked, mud mounds about two feet high, under overhanging, sharply pitched roofs, were crowded with large and small castings of the royal heads, figures of courtiers, ceremonial urns and vessels, and animals. Leopards were there, and rams, sometimes hollow, with a hole for pouring libations in the head. All the brass roosters, and all of them of almost exactly the same size, were found on one altar in their own compound, presumably therefore not an ancestor altar, but perhaps belonging to some special cult dedicated to some particular orisha or spirit.

All the altars, whether dedicated to the royal ancestors or to the spirits, were put to an exceptional amount of use between the massacre of the British Consul Phillips and his party in January 1897, and the arrival of the British Punitive Expedition in March, in a desperate effort to ward off retribution. The stomachs of the British soldiers and sailors were turned by the profusion of human sacrifices on all of the altars, the ground about them soaked and stinking of blood and entrails.

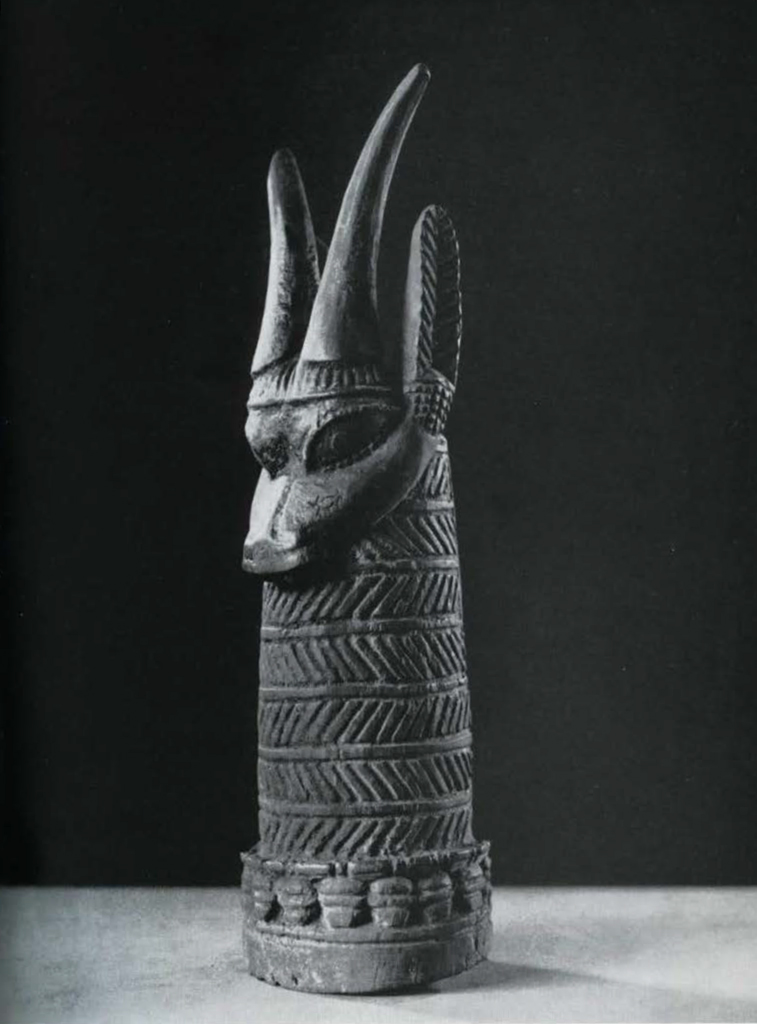

A RAM FROM THE OWO OF NIGERIA

Just as bronze ancestor heads were kept on the royal altars of the Obas or kings of Benin, the kings and chiefs of Owo, a Yoruba town sixty miles north of Benin, placed wooden rams’ heads (or human heads with ram horns) on their altars, the ram being known to have a special significance both in the ancestor cult and in the Yam cult. This excellent old sculpture seems to have been collected about the time of the Benin Expedition and may have come from the Owo quarter or possibly from the Yoruba quarter at Benin.

One other similar ram’s head surmounting a tapered cylindrical base, pierced with the same slot at the back for the insertion of a staff when in ritual use, is in America at the Chicago Natural History Museum. Both of these fine and rare heads have the beautiful and mystical quality characteristic of the best work of the Yoruba of Owo, and seldom if ever found in Benin work.

Image Number: 62503

Image Number: 62575

A SMALL BRONZE GROUP FOR A SHRINE

The baby elephants with their corrugated trunks ending in curled human hands in token of prehensility are stylized almost beyond recognition. They are accompanied by two men in flat open-work caps, whose features seem to be in Yoruba style. Perhaps the piece was made by a Yoruba sculptor as shrine furniture for some cult at Benin. This is suggested by the hollow square base embroidered with the interlaced igbo (“bush”) pattern so often seen in Benin work.

A YORUBA IVORY ARMLET

Such double ivory armlets as this, carved from a single section of elephant tusk and often patinated to a deep golden brown, were part of the ceremonial costume of Yoruba chiefs. The craftsmanship is equal to the best Oriental ivory carving in which a similar technique is sometimes used.

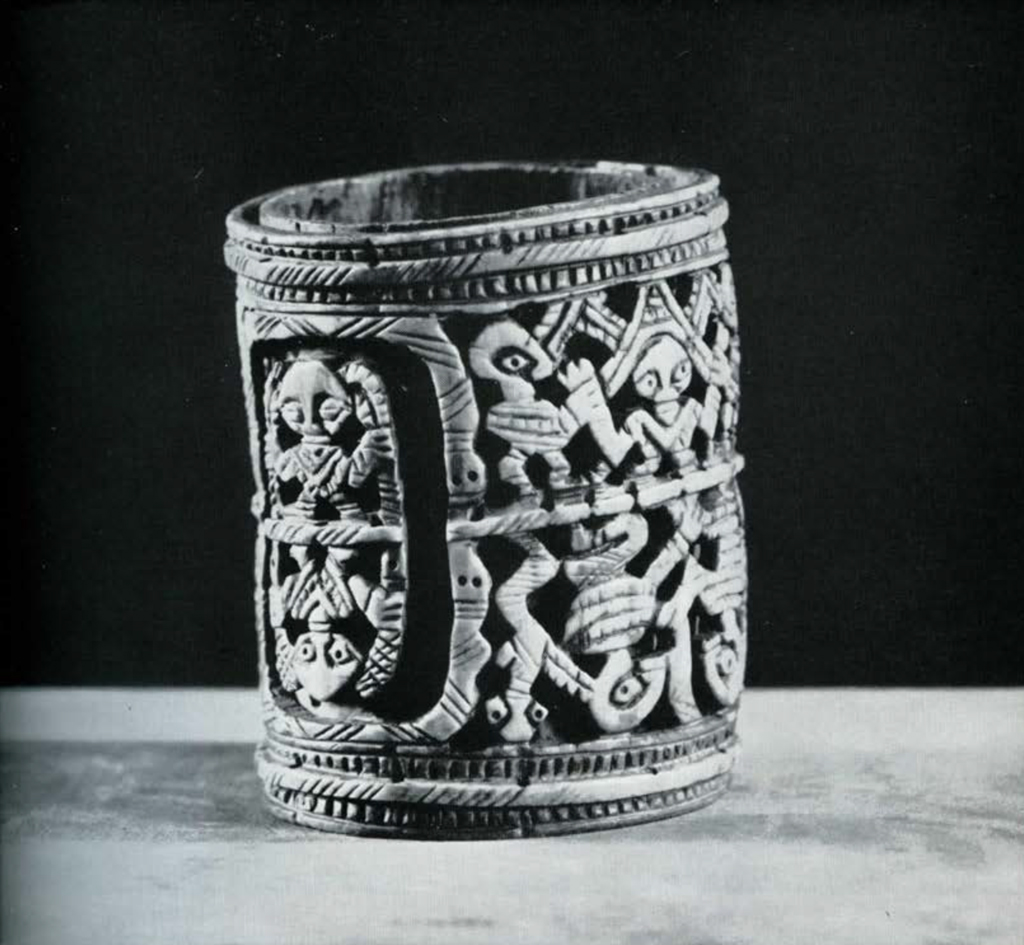

AN IVORY BOX AND AN IVORY CUP FROM BENIN

Many of the rarest and most beautiful of our African works of art were collected when Dr. George Byron Gordon was our Director. His taste and discrimination exercised in our behalf during his frequent trips to Europe resulted in our acquiring for the proverbial song these two magnificent ivory carvings which may date from an early period in Benin history.

The oval box, probably intended to hold valuable beads, shows two fighting Portuguese in sixteenth century dress-the gin bottle may be the secret of the battle. The strange position of the heads resembles an Ethiopian convention in painting faces in profile. The dragon-like beast pegged down by his tail is a pangolin, a scaly anteater found in West Africa. The box was brought from Benin by Sir Ralph Moor, the chief British administrator in southern Nigeria at the time of the 1897 expedition.

The ceremonial cup or bowl supported by four men is equally beautiful and interesting. Observe that one of the men is wearing a pendant cross, perhaps representing a courtier in the days of King Esigie when many nobles of the court were briefly converted to Christianity.

Image Number: 62568

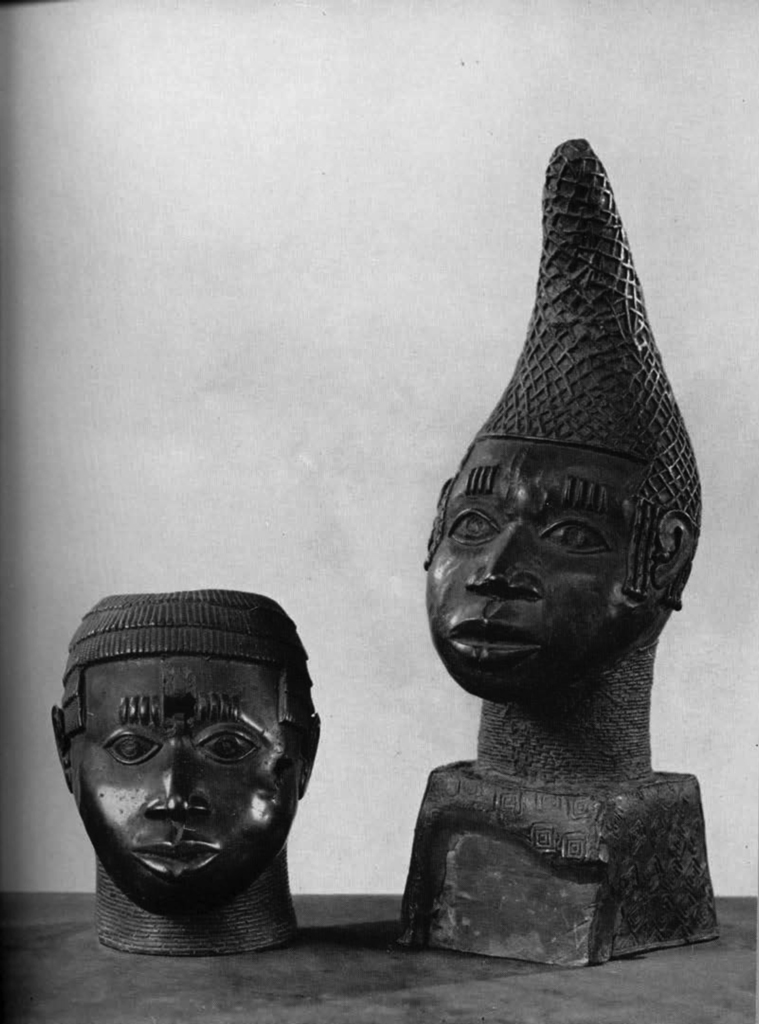

BRONZE HEAD OF A FIFTEENTH CENTURY KING AND A QUEEN MOTHER’S HEAD FROM BENIN

Of the many bronze heads of Benin make, this type of male head is by common consent the earliest. It is very thinly cast of naturalistic form with only slight stylization to be seen in the ears and the nostrils. Benin bronze casting derived from the naturalistic art of Ife, the spiritual center of the Yoruba tribe of Nigeria. It was about 1280, according to the oral tradition of the Bini, that the great Oba Oguola asked the Oni of Ife to send a master founder to teach bronze casting at Benin.

There is still a shrine to this first teacher, Igue-Igha, in the Street of Bronze Casters near the palace at Benin; and in these early heads dating perhaps from the fifteenth century, with their realistic subtlety, the lie derivation is still perceptible.

In the early sixteenth century the great Oba Esigie instituted the rank of Queen Mother for his mother Idia, and for her glorification were first cast the heads with high tapering headdresses, the best of which must rank high in any art history for their formal abstract beauty. This specimen, one of only five known, is remarkable for power rather than for delicacy of modelling.

Image Numbers: 62680, 62679

Image Number: 62681

Image Number: 62682

FOUR BRONZE PLAQUES FROM BENIN

For a hundred and fifty years, from the end of the sixteenth century, the walls and mud pillars of the palace courts were covered with heavy bronze plaques representing various Obas and courtiers, Portuguese officers, animals and birds and fish. Early travelers have described them in the days of Benin’s grandeur. But about 1750 they were torn down and stored in an outbuilding of the palace, where the rose-colored sandy soil of the country drifted over them and is still visible, encrusted in some of our plaques. Neglected for a hundred and fifty years until the British Expedition, they were rescued then from oblivion to take an honored place in the museums of the world.

Image Number: 62570

A CROSS BEARER AND THREE PENDANT MASKS FROM BENIN

The Benin kings and chiefs wore a kilt-like skirt pleated and knotted over the left hip; over the knot was tied a bronze mask, or sometimes two or three, often in human form and about hair life size. These three masks are particularly notable and of the very best and rarest types. The fanciful synthesis of the features with snakes and fish, elephants with the trunk ending in a human hand, distinguishes them from the most often seen type in which the face closely resembles that of the big heads with tusks.

The tall figure of a courtier of Benin has the crux decussata hung about bis neck on a chain. Such large, elaborate, and unmistakably decadent sculptures as this adorned the royal altars as the power of the Oba decreased, bronze props for his tottering prestige.

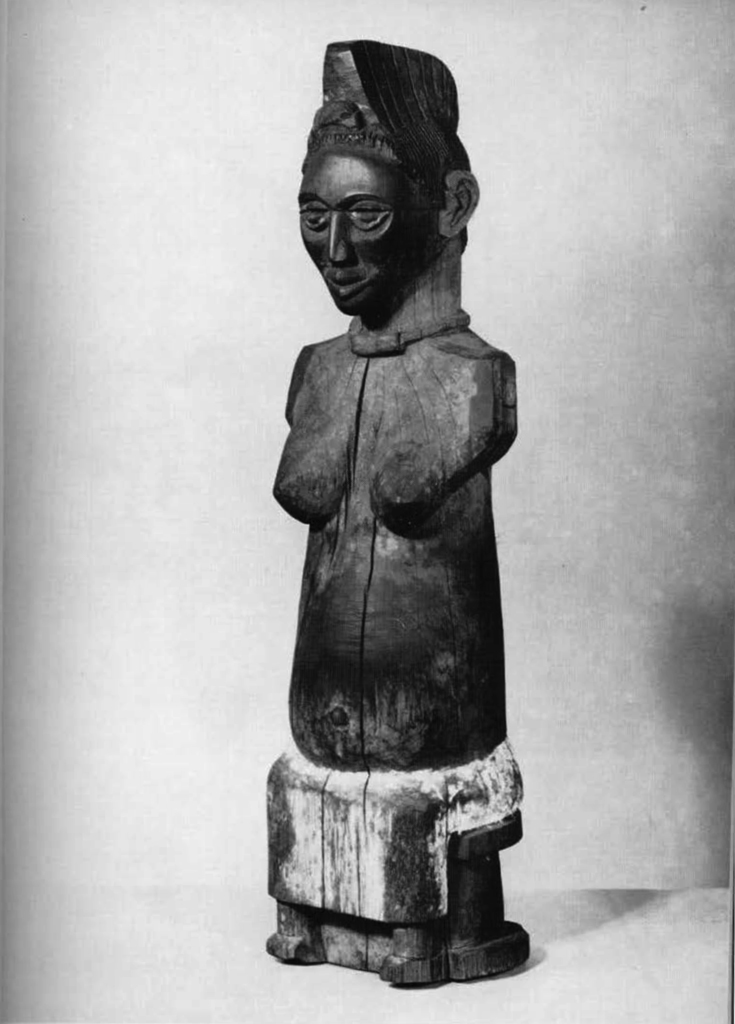

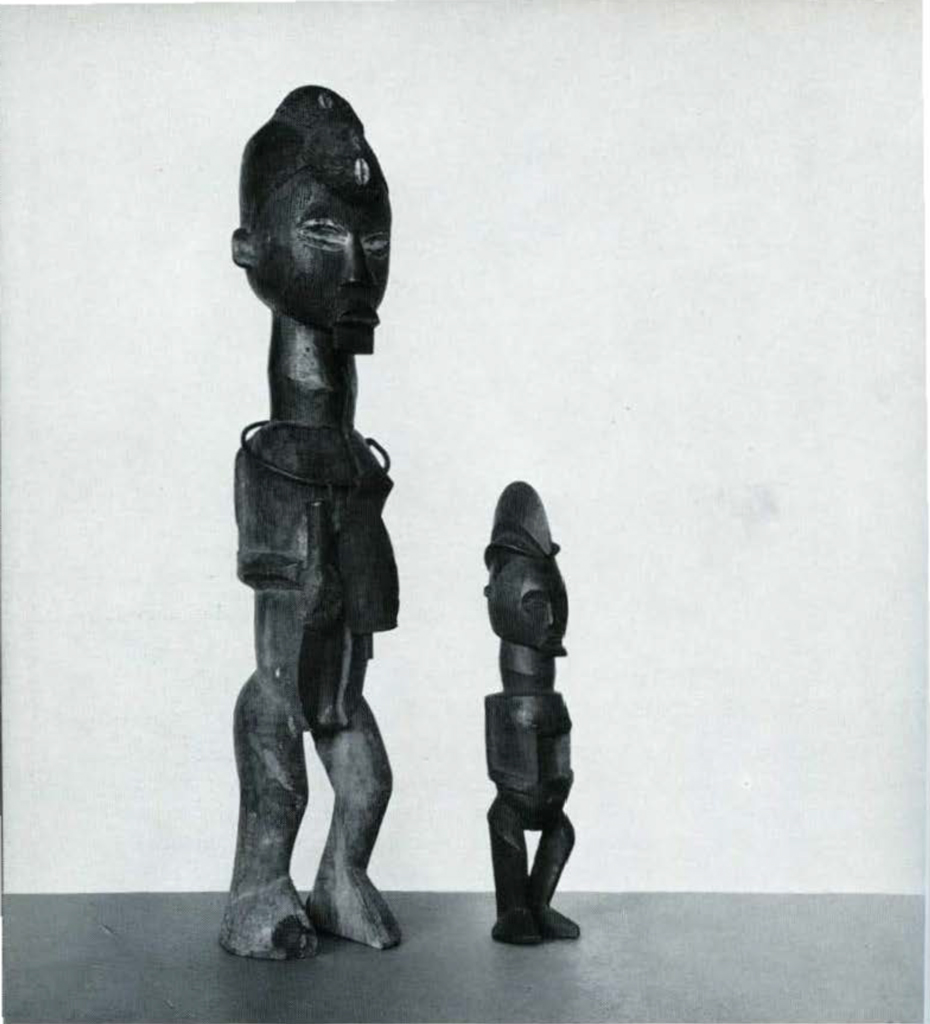

A GREAT AFRICAN SCULPTURE

In 1916, in one of the first books on African art published, Negerplastik by Carl Einstein, is illustrated without attribution this splendid sculpture, to this day an enigmatic masterpiece. Many provenances have been suggested by scholars: the Yoruba of Nigeria, Madagascar, the Ibo or Ibibio of the Niger Delta, the Bakongo of the Belgian Congo, but none is provable.

Among the Ijo, who live by fishing in the creeks and mangrove swamps of the Niger Delta and whose art is more starkly cubistic than that of any other African tribe, there nevertheless existed an anomalous naturalistic style at the court of the kings of the old trading port of Brass. Several specimens representing members of the family of King Ockiya were given up to the English missionaries about eighty years ago on their conversion to Christianity and are now in British collections. Recently a British anthropologist, Horton, has found a similar naturalistic style still extant not far from Brass, which Fagg, of the British Museum, thinks is possibly associated with the old style of the family of King Ockiya.

The “royal” figures vary up to life size and have separate arms, attached by pegs, as did this figure at one time. If this stately sculpture with its proudly regal head comes from Brass (and it would fit quite well into this series although the attribution is still highly speculative), it is the best and smallest example known of its species. And whatever its secret may prove to be, it is certainly one of the greatest of all African sculptures.

Image Number: 62585

Image Number: 62587

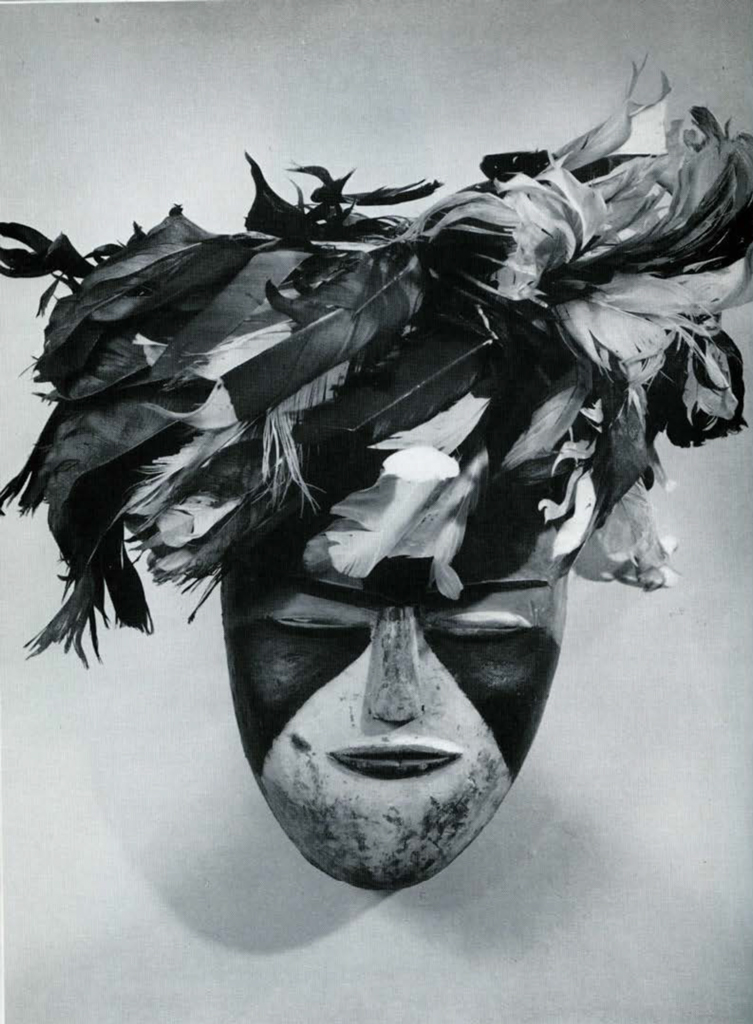

FEATHERED-CRESTED DANCE MASK

From somewhere in the Congo, probably from the Gaboon, comes this wonderful polychromed dance mask with its coiffure of curly feathers. It has been attributed to the Balumbo, but it might also be from the Fang, or even from the Bakongo. Frobenius, the great German ethnologist, illustrates a more or less similar mask in his Die Masken und Geheimbünde Afrikas (1898) and calls it Loango. In so evocative and imaginative an artistic creation, it is enough to be uncritically admiring, being certain only that it was sculptured by a great master of Western African art.

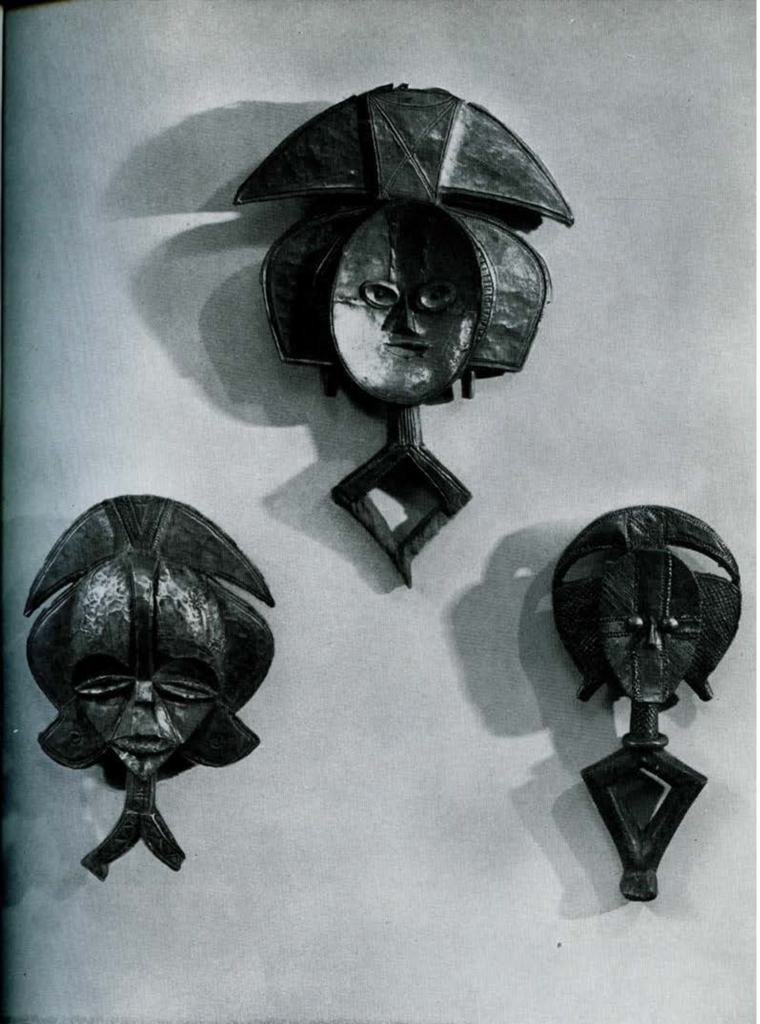

THREE BAKOTA FUNERARY FIGURES

Picasso, in his portraits showing profile and full face superimposed one upon the other, adopted, whether consciously or not, the trick of the Bakota artist who created the style of these flat, two-dimensional funerary figures. The Bakota coiffure is almost always surmounted by a clay-dressed crest, running from the front to the back of the head. Since the carved and metal-plated figure is made to go against a wall, it was simple to turn the crest and make it a lunar frame for the face, terminating in side pieces with their cylindrical earplugs. Faces and necks are decorated with narrow brass or copper strips, or they are covered with thin metal sheets of brass or copper hammered and punched with simple designs.

The Swedish scholar, Andersson, who has recently published a treatise on the Bakota of French Equatorial Africa, says that the heads with their bodies represented by what may be only arms held akimbo, are spirit figures. We know that they were fastened to reliquary baskets in which were treasured the skulls or other bones of revered ancestors, and were kept in family shrines or against the walls of the men’s society houses. Offerings were made to them, and supplications; the ancestors’ bones and the spirit figure above them seem to have been intermediaries between the living tribesman and his god.

Figures of this type were among the most popular with the School of Paris in the twenties, and are becoming more and more rare and highly valued.

A BAKOTA FIGURE

Conventionalized, abstract in the pure sense, is this rare figure in the round from the Bakota. To call it an ancestor figure, as originally described in our museum catalogue, is easy enough: it has a hieratic look. But so few-only five-of these pieces have been collected and described in the literature of African art that, in the absence of documentation, it is futile to make any statements regarding their use or purpose in the Bakota tradition. All that we know, from the characteristic coiffure and features and from the style of the stool, is that this is a sculpture from the Bakota, a great work of art.

A LINTEL FROM THE CAMEROONS

The lively monkeys adorning this wooden door lintel from the Bamileke of the Cameroons Grasslands show the exuberance and imaginative realism characteristic of the art of this tribe. Such lintels, doorposts, and house posts were reserved exclusively for the houses of the chiefs of this area.

Image Number: 62684

DANCE MASKS FROM THE BALUMBO

The Balumbo, like the Bakota, the Bakuele, and the Fang, are greatly preoccupied with the propitiation of ancestor spirits; and a men’s secret society of this tribe, called the Mukui, specializes in an elaborate funeral dance performed on stilts, with the dancers wearing long white cloths that reach to the ground and these small masks, always freshly painted white. They are said to represent the spirits of dead maidens. The Oriental cast of the features is curious but fortuitous. Though these masks are commonly attributed to the Balumbo, they were used also by the M’Pongwe, Mashango, Ashira, Bakota, and other tribes of the Gaboon.

Image Number: 4994

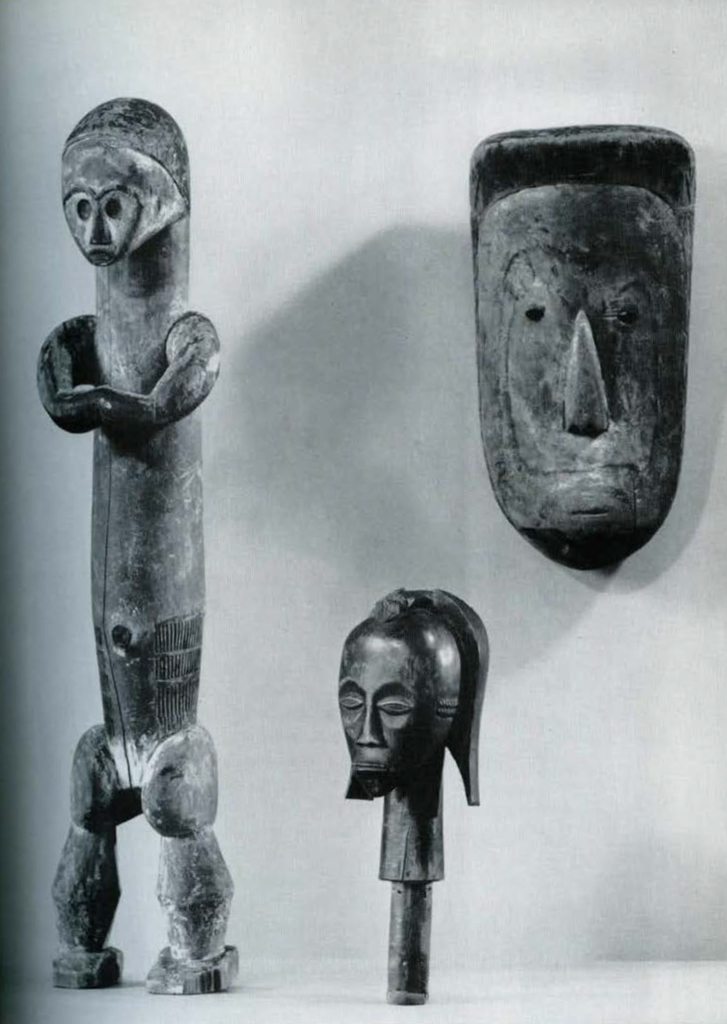

A SCULPTURED HEAD, A STANDING FIGURE, AND A DANCE MASK FROM THE GABOON AND SPANISH GUINEA

The skulls of revered ancestors, minus their mandibles and rosily polished with palm oil and powdered camwood, were kept by the Fang people in cylindrical wooden boxes in their shrines. To guard the ancestor spirits, which dwelt in the cherished skulls (often two or three in one box), the Fang carved tutelary figures with tail-like stalks for attachment to the reliquary, or beautifully sculptured heads with coif-like headdresses whose long necks acted as attachment stalks. Such a head is shown here, a great work of dignity and quiet beauty.

The more stylized, long-torsoed female figure is a variant on the usual theme, rubbed with kaolin or lime, not of oil dark hardwood like most of the guardian figures. With short arms joined over non-existent breasts, it lacks the usual stalk for attachment, but we are showing it instead of one of the more typical figures because of its extraordinary sculptural form.

Less beautiful and very simple are the light wood dance masks used by the Fang, such as this one. Similar masks are used by various tribes of the Gaboon, both in secret society ceremonies and in tribal dances.

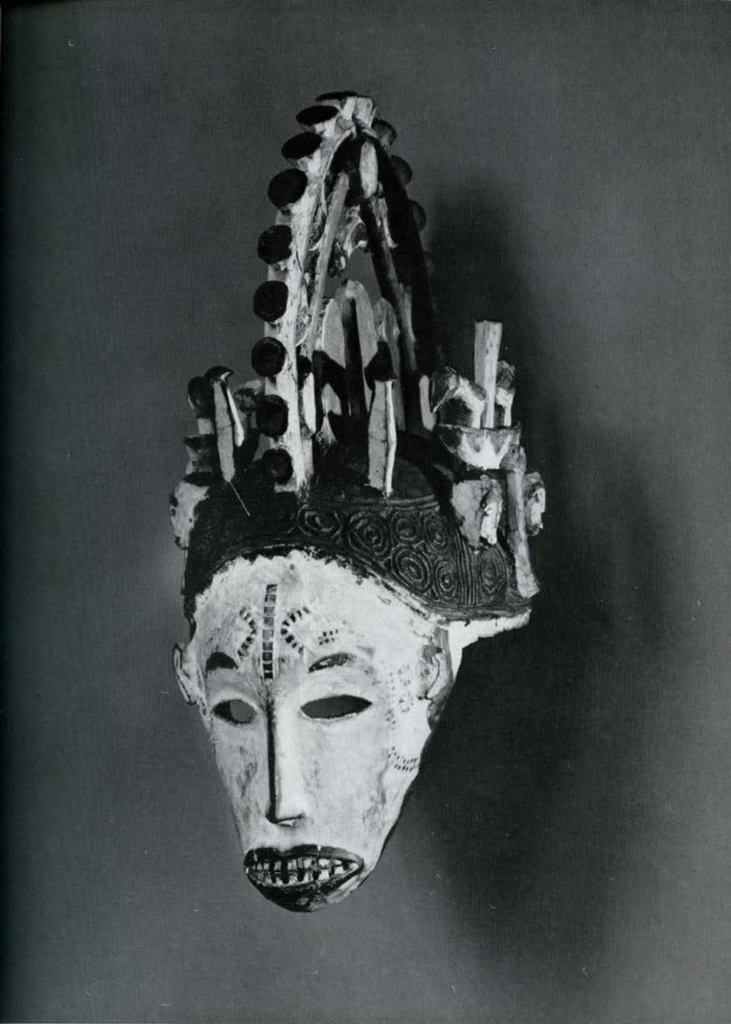

A FAMOUS IBO DANCE MASK

This crested helmet mask from the Ibo has been illustrated in many books on African art and exhibited in numerous museums throughout the country. The members of the Maw society of the Ibo of Nigeria use several of these masks in their most famous dance-play, one that calls for expert dancing and long practice. According to Kenneth Murray, who has written of these masks, they are worn at dances commemorating funerals of members of the Maw society and, along with their tightly fitted, brightly colored costumes, appliqued with bright red and yellow cloth, are usually made to order for the individual male dancer. The strangeness of the face, with its long thin nose, its oval shape, its mouth with even rows of tiny teeth, and its general air of aristocratic aloofness, is characteristic. These are said to be the faces of dead maidens of great beauty, and in the dance with them another masked figure appears, representing their mother, the maternal spirit. These masks are invariably white, as was this one when first collected. Among the Ibo, as among the Balumbo, Bakuele, and Fang, white is the color of dead spirits.

Image Number: 4988

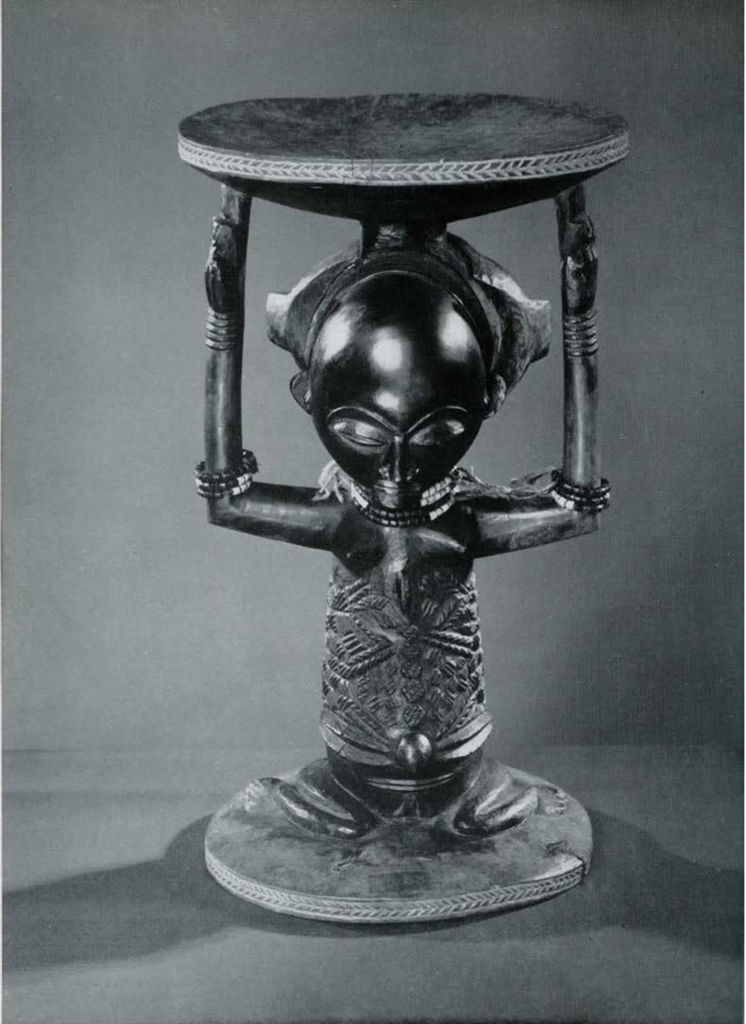

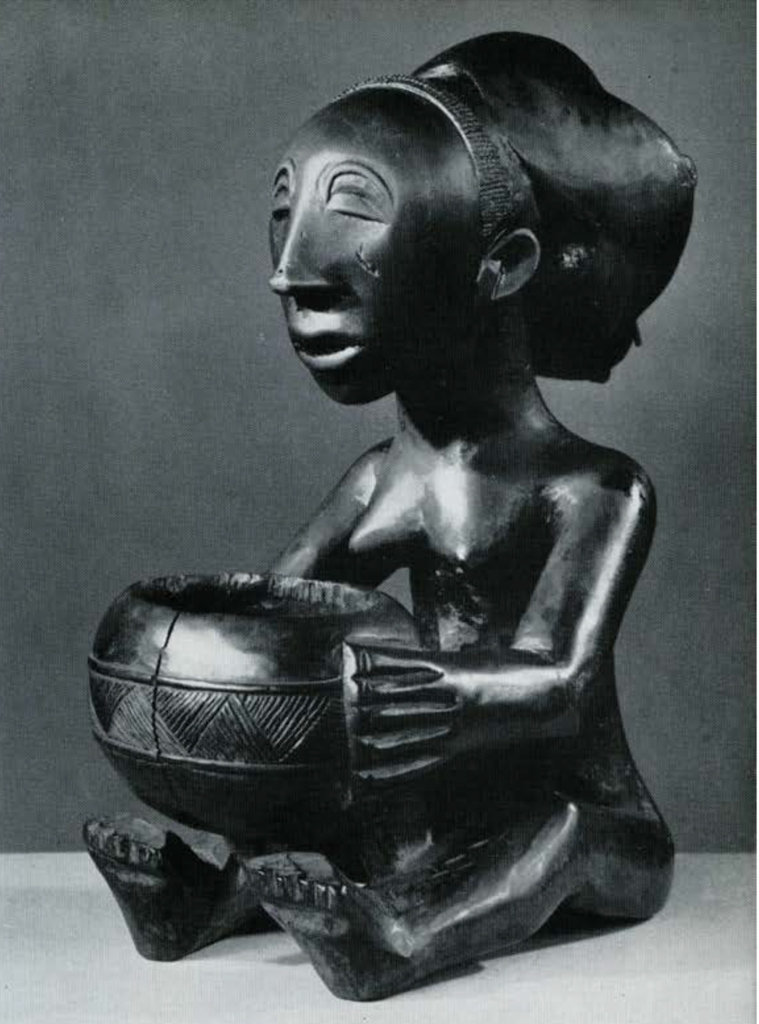

TWO BALUBA SCULPTURES

The sculptor of the Belgian Congo who, with such extreme sensitivity, ed this woman holding her decorated calabash bowl, may have been a pupil of that great master of Buli, a northern Baluba village in the Belgian Congo, whence came twelve of the greatest masterpieces of African art to be found in the world’s ethnographical museums. All the great textbooks of Negro sculpture illustrate one or several of them; many photographs of them can be seen in our library. Both this figure and the kneeling woman holding aloft a calabash bowl to act as a stool, are great and beautiful sculptures and easily rank among the top twenty of our African works of art.

Image Number: 4969

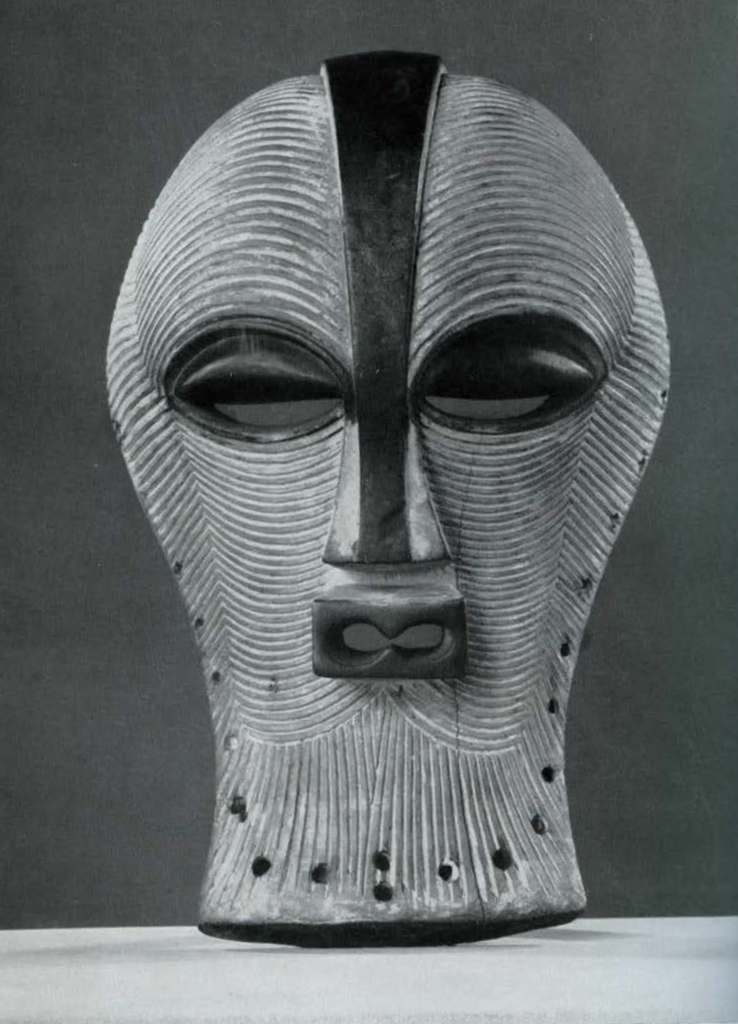

FETISH FIGURES AND DANCE MASKS FROM THE BASONGE AND THE BALUBA

Strongly stylized fetish figures like these are produced in enormous numbers by the excellent carvers of the Basonge, who also specialize in equally cubistic masks, often called kifwebe, (though this is only the Chiluba word for mask) decorated with deep parallel incisions which are filled with whitish clay. The Basonge, like their neighbors the Baluba and the Bajokwe, are descended from the Lunda kingdom of the Middle Ages and share a number of stylistic conventions in their kifwebe masks. Angular and cubistic forms distinguish the Basonge work, however, while the Baluba are more fluid and gentle in their style. Basonge figures, nearly all male, are carved with the hands resting on the abdomen.

The kifwebe masks are said to be worn by witch doctors, fetishers, in a slow and stately dance with a whirling finale, a dance that gives added power to the fetish.

Image Number: 62687

Image Number: 774

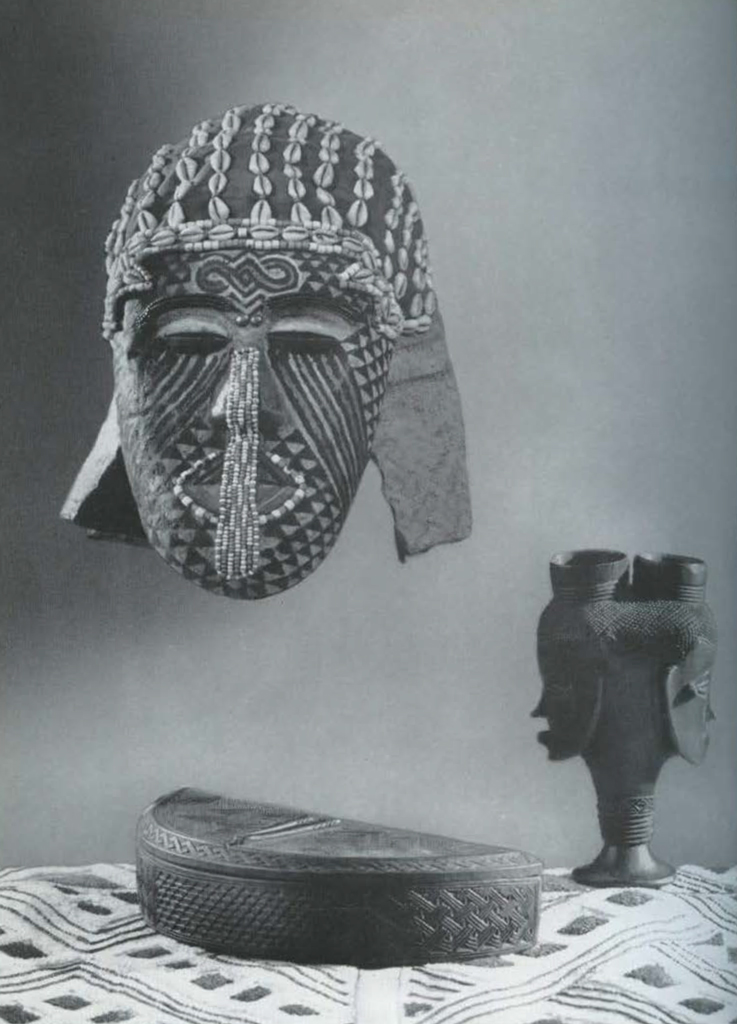

MASK, A COSMETIC BOX, AND A CUP R PALM WINE FROM THE BUSHONGO

The Bushongo or the Bakuba is one of the largest nations of the Belgian Congo, possessed of an oral history supposed to cover some fourteen hundred years and a hundred and twenty-four kings of the same line. Their prestige as artists is very high and they have strongly influenced other tribes as well as their sub-tribes, particularly in the decorative arts. Here, in this box to hold the rose-colored camwood powder they use as rouge, in the cup for the ritual drinking of palm wine, in the embroidered pile raffia cloth, we can distinguish motifs of decoration perhaps introduced many centuries ago and synthesized with the local Bantu techniques. See the weevil, mutu chembe, the head of God; ikuni na woto, the tribal ancestor; lori yongolo, the chameleon’s foot; yongonyo, the grasshopper; imbolo, interlacing; and on the box, mikope ngoma, the drum pattern of King Mikope Mbula, the 110th king, who ruled in the early nineteennth century.

The mask, which covers almost the entire head of the wearer, is elaborately decorated with beads and cowrie shells. It is said to be of the royal type and highly valued as a mask worn in dances in which the king himself would participate.

TWO FIGURINES FROM THE BATEKE OF THE CONGO

Bateke sculptors have produced very little but fetish figures, many of them so covered with magic gums and “medicines” that only the characteristic bearded faces with parallel striations on the cheeks can identify them as members of this tribe. One of these two sculptures has never been treated as a fetish, but in the larger the characteristic accoutrements of a Bateke fetish may be seen.

A DANCE MASK FROM THE BUSHONGO OF THE BELGIAN CONGO

Through the secret slits in the eyes of this classically beautiful helmet mask, the Bushongo dancer could watch the response of his audience as, full-skirted in embroidered raffia cloth, he went through the figures of his dance for the pleasure of the king and his court.

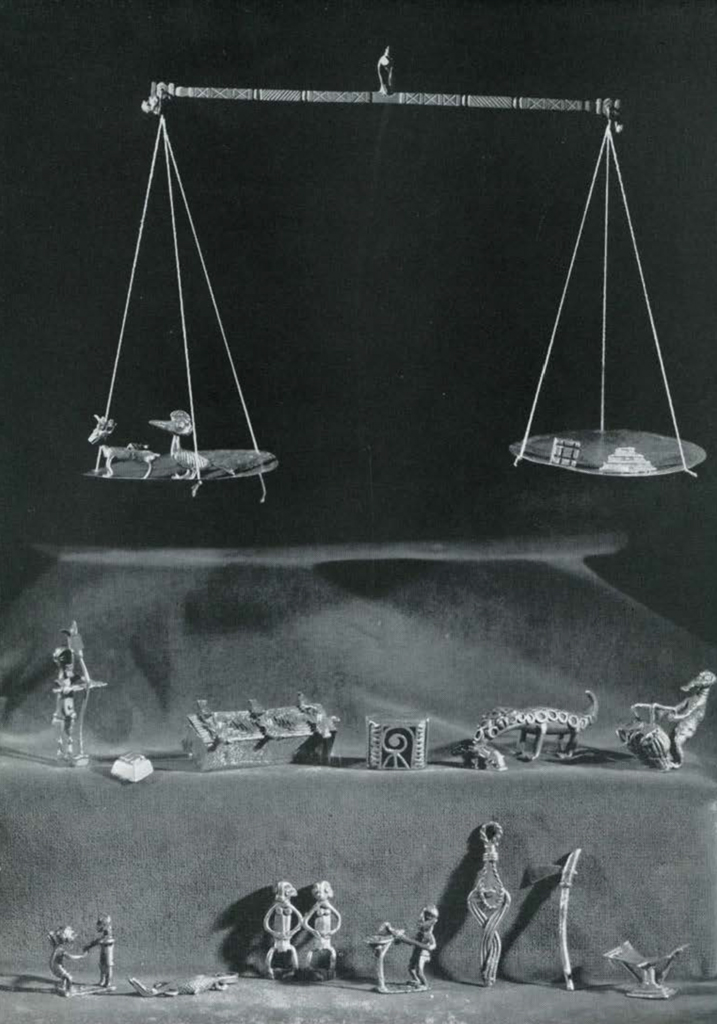

ASHANTI GOLD WEIGHTS, A BOX, AND SCALES

Centuries ago, before the introduction of gold and silver and copper coins to the Guinea Coast, the Ashanti people used gold dust or gold nuggets weighed out on small scales with such ingeniously cast brass sculptures as here shown for weights. Gold weights were sometimes – for a king – cast of real gold, occasionally of silver or copper, but brass and bronze were the metals most commonly used.

This group of representational and geometric weights are all of brass, and in these small sculptures is mirrored the daily life of the Ashanti people. Men and women engaged in ceremonial rites and domestic duties, birds and animals and fish and reptiles, pots and stools and swords and drums, all are cast by the cire perdue (lost wax) process in which the sculpture is first modelled in wild beeswax, dipped thickly in porous clay and let dry, then heated until the wax is “lost,” melted into the clay investment that surrounds it or evaporated into gas, and quickly replaced with molten metal.

The boxes for the gold dust or nuggets were similarly cast.

Recent research suggests that the Ashanti-Baule system of weights is related to one found in India, both having the red seeds of the boris precatorius as their basic unit of weight.

Image Number: 62690

Image Number: 62693

A DANCE MASK AND THREE IVORY AND WOOD PENDANT MASKS FROM THE BAPENDE

Someone of great artistic originality surely carved this sensitive dance mask from the Bapende tribe of the Belgian Congo. It was made to be worn at dances celebrating the end of the circumcision ceremonies, when thee boys were reborn as adult members of their tribe.

The small pendant masks are similar in style to the dance mask. To us, all have dead or sleeping faces, with closed eyes and serene expressions, representing the soul before rebirth, but according to the great African scholar, Father de Sousberghe, this is an European interpretation, denied by his informants. Bapende men wear them throughout their lives after graduation from their “bush universities.”

Image Number: 62694

Image Number: 62601

A DANCE MASK, A STAFF, AND AN EQUESTRIAN FIGURE FROM THE BAJOKWE

The ancient kingdom of the Lunda spread over the western Belgian Congo and Angola (the Portuguese Congo) in the Middle Ages; and the Lunda and Bojokwe (alias Badjok, Chokwe, M’Bundu, Kioko, Vatchivokoe) tribes were its dominant force, progressive and aggressive, spreading widely about the surrounding country and influencing their weaker neighbor tribes, as well as absorbing influences from them, from the west coast to the shores of Lake Tanganyika in the cast.

The staff with its magnificently sculptured head and the beautiful and sensitive dance mask have long been in our collections. The mask, decorated with brass nailheads, is complete with head covering of woven raffia cloth. The complete costume must be imagined-of tightly fitted crocheted vegetable fibre, with bunches of rattles and bells at wrists and ankles, in violent and rhythmic movement, lit by torches and moonlight, accompanied by tribal drums.

The small equestrian figure is by a more imaginative sculptor than are most of the similar descriptive carvings. It has been treated with magic substances to enhance its power.

Image Number: 62583

DANCE MASKS FROM THE BAYAKA AND THE BASUKU OF THE BELGIAN CONGO

Only recently have the art and culture of the Bayaka been distinguished from that of their neighbors on the west, the Basuku, for many years known as the Western Bayaka. In both tribes the boys are trained intensively for a year in “bush schools” apart from their villages, whence, after circumcision ceremonies, they emerge as adult members of the tribe. Dances and feasts, with processions through their villages, then take place, the boys competing to obtain the most fanciful of these dance masks, built up (in the case of the Bayaka) of bark cloth over a reed framework, to cover the whole head, with only the face itself carved of wood; the Basuku mask however, is of helmet type, carved from one piece of wood.

Image Number: 62697

NATL FETISHES FROM THE LOWER CONGO

These magnificent figures, evocative of witch doctors and magic charms, sorcery and evil spells, are excellent examples of the konde (nail fetishes) of the Bakongo people of the Lower Congo. Contrary to popular opinion and European practice, the witch doctor is not asked to pound a nail or a spike or a knife into that part of the fetish’s anatomy where the patient is suffering, but the iron is used as an added strength to the supplication, and it will be noted that only the torso is nail-studded. Great lumps of magic pastes and gums, a veritable witch’s brew, are inserted in cranial and abdominal cavities. These, like the nails and knives, add potency and efficacy to the fetish. The carver wastes no sculptural interest on the front of the body, because this is conceived of only as a vehicle for the nails which are soon to cover it.