Middle East

Trace the story of how ancient Mesopotamian societies gave rise to the world's first cities

Main Level

Included with Museum Admission

Above: Lyre Fragment, Iraq, 2450 BCE, B17694B

Trace the story of how ancient Mesopotamian societies gave rise to the world's first cities

Main Level

Included with Museum Admission

Above: Lyre Fragment, Iraq, 2450 BCE, B17694B

The Middle East Galleries vividly illustrate how the first settlements led to the first cities, and how our modern urbanized world can be traced to innovations in ancient Mesopotamian societies.

Above: Lyre Fragment, Iraq, 2450 BCE, B17694B

Ten thousand years ago, in the fertile crescent of the Middle East, a transformative point in our human history was set in motion. The domestication of plants and animals prompted the shift from hunting and gathering to farming, establishing the first settled societies. Villages developed, then towns, then cities, accompanied by social and technological developments like writing and mathematics.

The story of the ancient Middle East is one that the Penn Museum can tell uniquely well: the Museum was founded in 1887 to house artifacts from its expedition to Nippur, the first American-led archaeological project in the region. Since then, the Museum has excavated an unparalleled constellation of sites in the Middle East, where active research continues today. The Middle East Galleries highlight the Museum’s pioneering research, centering cultural heritage work as we make new discoveries each year.

The inscription on this calcite disk marks the world’s first identifiable author as a woman —the high priestess Enheduanna. B16665

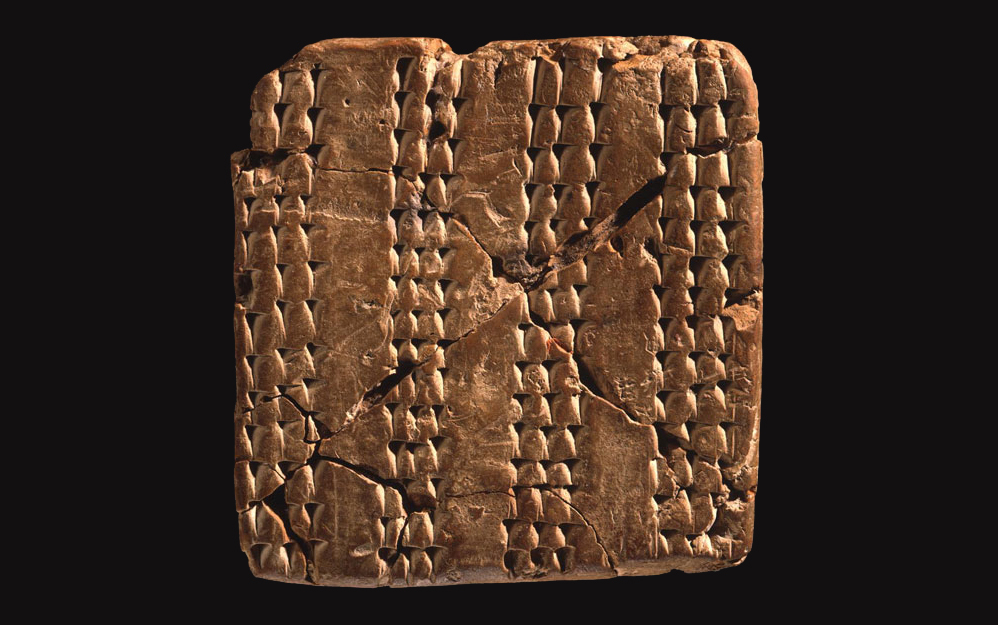

In ancient Mesopotamia, children who were to become scribes would practice writing by impressing repeated cuneiform characters on clay. This 4,000-year-old unbaked clay tablet depicts the single vertical wedge repeated over and over across its surface. CBS6043

This reconstructed jar, found inside a well-preserved Neolithic house, is one of the oldest known wine storage containers in the world. 69-12-15

In early Mesopotamia, even elite women were generally described in relation to their husbands. A cylinder seal found in Queen Puabi’s burial chamber identifies her without the mention of a husband—indicating that she might have a been royal ruler in her own right. She was buried wearing an elaborate ensemble, including a headdress made of wreaths of gold, beads of lapis and carnelian, a gold support comb, and more than 30 feet of gold ribbon—weighing approximately five pounds.

Learn More

Museum Shop

Add some royal splendor to your collection with this carnelian and lapis necklace inspired by the ensemble worn by Queen Puabi of Ur.

Led by Holly Pittman, Ph.D., recent work at the site of Lagash reconstructs the ancient environment of southern Iraq through remote sensing, geological coring, and excavation, leading to the groundbreaking discovery of a 5,000-year-old tavern.