The objects forming the present collections of the University Museum were acquired in various ways. In the early days-the Museum was first opened to the public in 1898-a number of objects were purchased from dealers in this country and abroad, while others were presented by public-spirited Philadelphians. From the very beginning the Museum had subscribed to the British excavations in Egypt, and some of our outstanding pieces, especially those dating from the beginnings of Egyptian history, are the results of these subscriptions. Later through the liberality of the late Mr. Eckley Brinton Coxe, Jr., the Museum was able to send out its own expeditions and thus, through the liberal attitude of the Egyptian Government of those times, the bulk of the collection was very considerably increased.

These expeditions of the University Museum have been carried out in the following places:

- At Areika, Anibeh, Karanog, and Buhen in Nubia, 1907-1910.

- At Memphis, 1915-1919 and 1921-1923.

- At Giza, 1915.

- At Dendereh, 1915-1918.

- At Thebes (Dirah-abu’l Negga), 1921-1923.

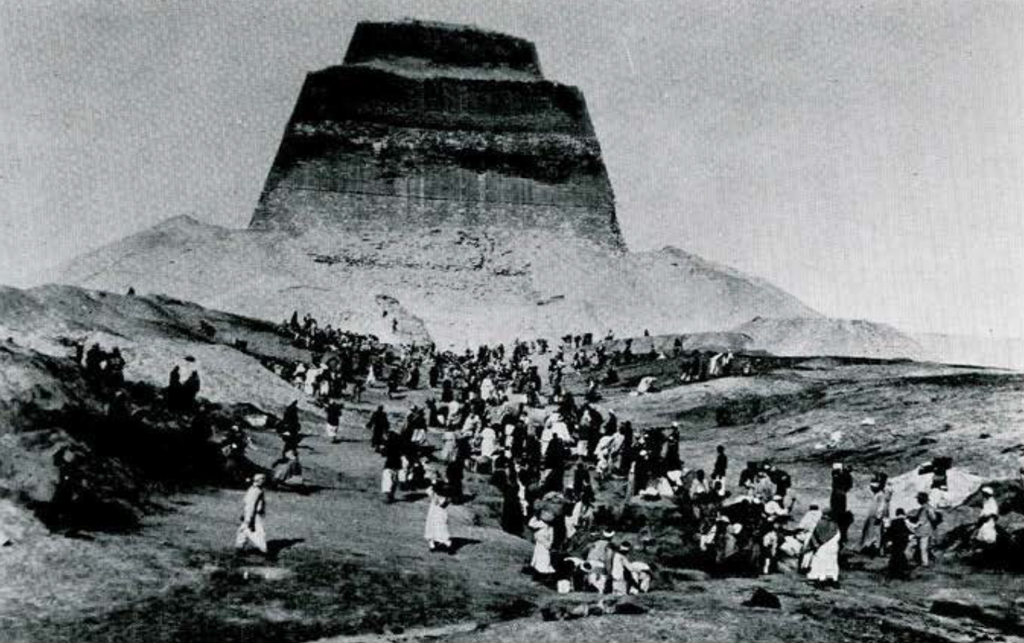

- At Meydûm, 1929-1932.

- At Beisan in Palestine, 1921-1923; 1925-1927; 1930, 1931 and 1933.

Image Number: 32749

THE UPPER EGYPTIAN HALL

The Egyptian antiquities have been exhibited on two different levels: in the large “Upper Egyptian Hall” or “Hall of Statuary” with its five small adjoining rooms, and in the large “Lower Egyptian Hall” with one smaller room adjoining.

Only the objects in the Upper Hall of Sculpture have been arranged in an approximately chronological order, and here we shall begin our review of the collections. As we enter the Hall from the Chinese rotunda, we find ourselves at the beginnings of Egyptian history proper, but as our glance travels over the many objects to the opposite wall we pass through millennia down to the time when Roman Emperors were lords of the Nile Valley.

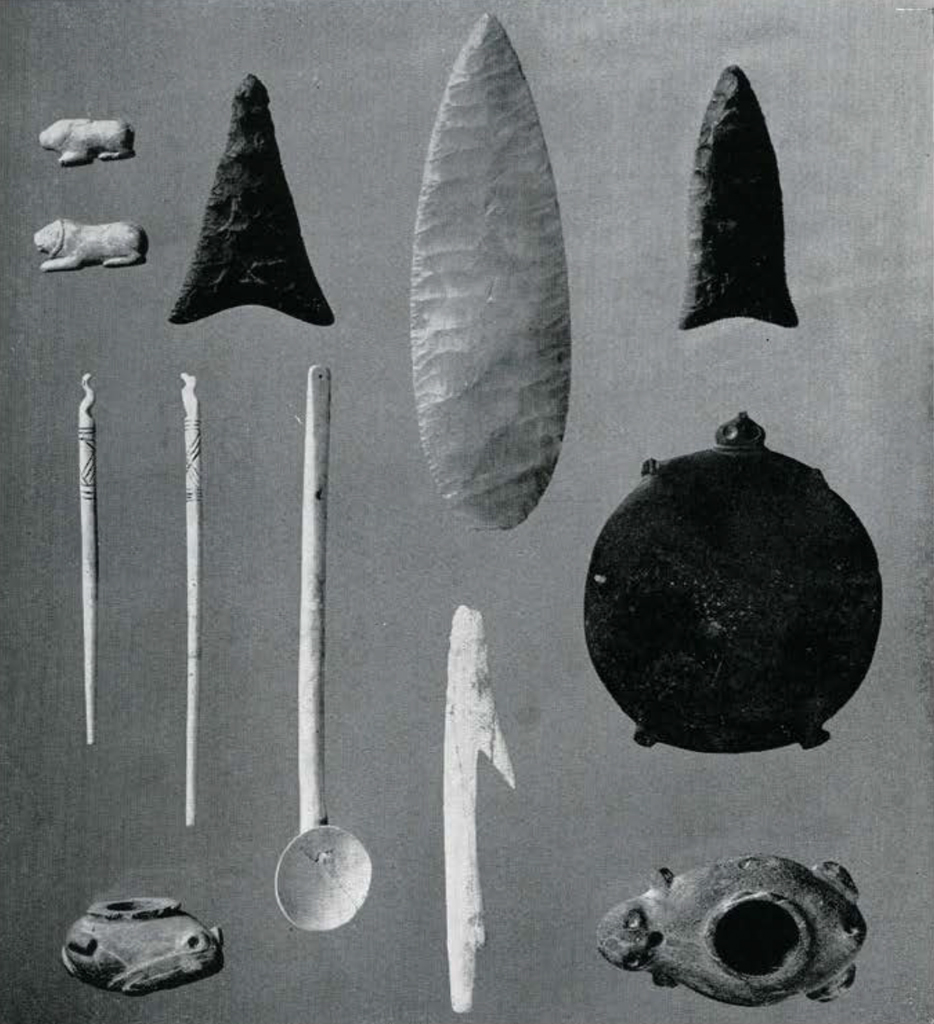

Before regarding these objects in detail, we should cross over to the second small room on the right side, that is, if we are interested at all in the prehistoric beginnings of Egyptian civilization. Amongst the objects exhibited in the left center table case we find a small group of remains from a very early settlement in the Southwestern Delta (Merimde) and quite a number of objects from prehistoric tombs of Upper Egypt from the time of the fourth and perhaps fifth millennium B.C. These are implements and other objects of daily use such as tools of flint, bone and ivory, and combs, hairpins and slate palettes (fig. 7). On the slate palettes was ground, with desert pebbles, the eye paint which the most ancient Egyptians used.

Image Number: 34389

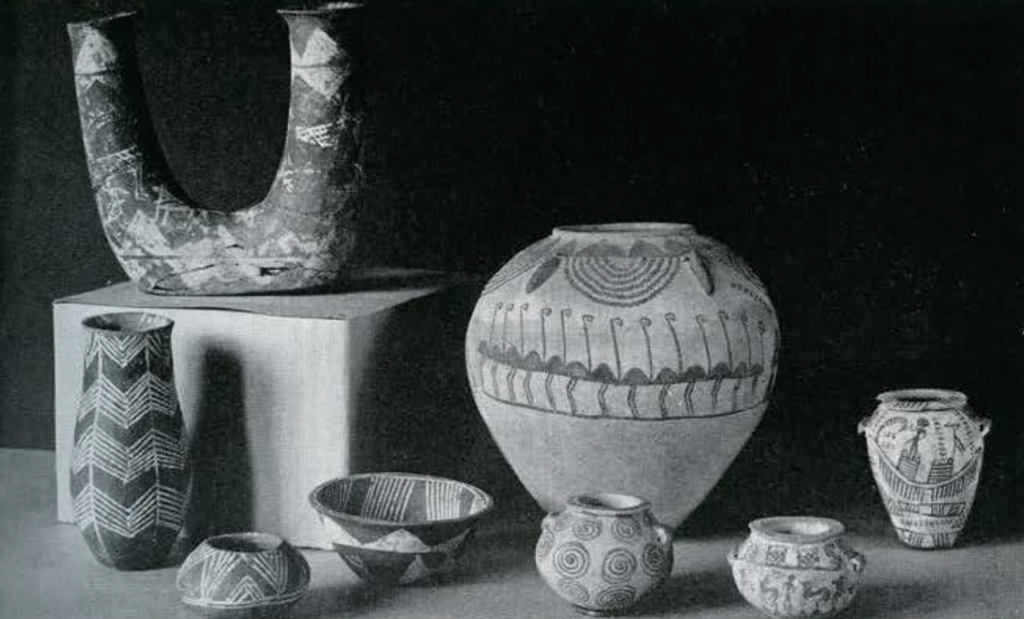

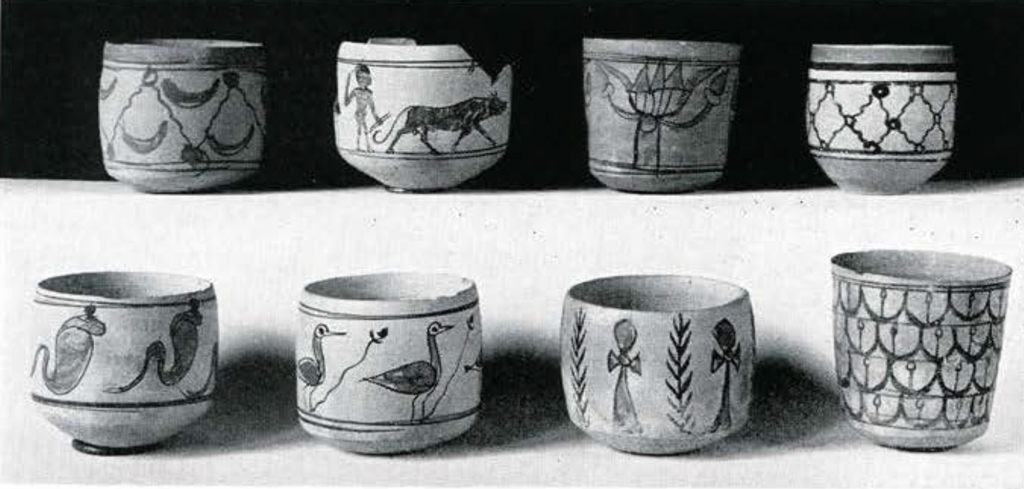

In two of the larger cases, there is a selection of painted and unpainted pottery, representing the civilizations known as Nagada I and Nagada II, some of them showing very pleasing forms and interesting designs (figs. 8 and 9). Two more cases display specimens of stone vases and bowls, of astonishing technical perfection and made of various kinds of stone, from translucent alabaster to black basalt and stones of beautiful pink hues (fig. 10). They all come from tombs, and some of them belong to the earliest two dynasties. One high alabaster vase (9510) shows the well carved name of King “Narmer,” who is either identical with “Menes,” the traditional founder of Egyptian history, or a contemporary of his. A small high vitrine contains a number of ivory carvings, mostly human figurines, also belonging to this early period (fig. 13).

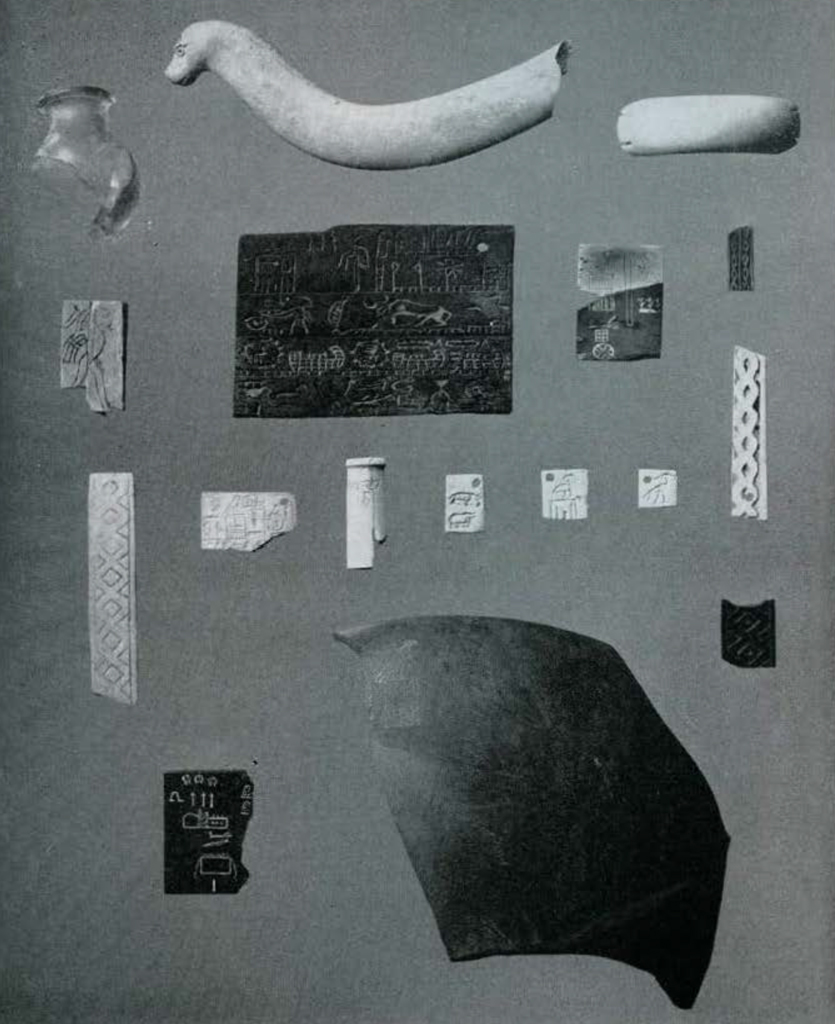

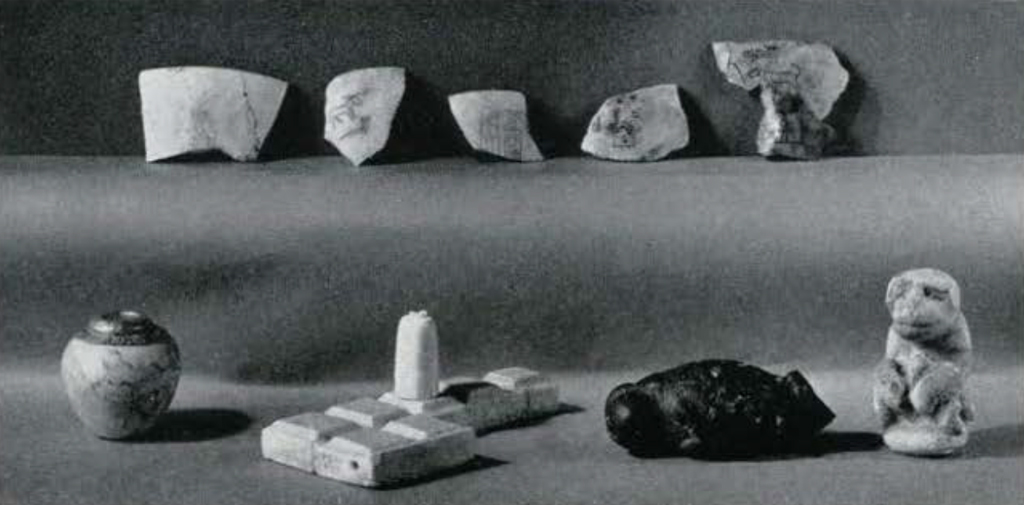

In the two table cases nearest the wall are exhibited a number of objects dating to the first two dynasties, nearly all of them from Abydos, where the archaeologist Petrie discovered royal cenotaphs and private tombs of this period (figs. 11 and 12). The presence of so many inscriptions among these objects is significant. They almost certainly represent the earliest use of a script in Egypt, and this development must have been of great importance in expressing and maintaining unity throughout the newly joined two lands. Some use of writing may already be traced in pot marks of the earlier cultures, but now for the first time consistent and consecutive employment is made of the signs as we know them from later and fuller texts. The inscriptions we have here are very brief and in many cases give only the names and titles of the kings; even the longer statements are so condensed that their phrases cannot be read with any certainty. And this uncertainty is increased by a tendency to place the signs in the order which best fills the space to be inscribed. Of particular interest is the class of brief notices which give the event or events of a year of some reign, as indicated by the curved sign for “year” on the right. An example of this may be seen in the small ivory tablet in figure 11, and in the large jar near the entrance to the Upper Hall. Many tablets are evidently labels of some kind, and in some cases (but not in these examples) bear numbers on the back. The founders of the first dynasty adopted the cylinder seal directly or indirectly from Mesopotamia; unlike the earlier Sumerians, however, the Egyptians covered the surface of their seals with writing. A remarkable feature of nearly all these archaic Egyptian inscriptions is the excellent proportioning and execution of their signs. Another surprising feature is the appearance of cursive writing, done with pen and ink, of which a few very fragmentary examples are to be found in the left-hand case.

Retracing our steps and returning to the entrance of the big Hall, we are at once confronted with some of the outstanding treasures of our collection. The first object before us is a door-socket of hard black stone, from the entrance door of the main sanctuary of Upper Egypt at Hierakonpolis (fig. 14). It is carved to represent the figure of an enemy, who lies on his belly, with his arms fettered behind him. The heavy wooden temple door once turned upon the pole which fitted into the hollow depression in the captive’s back, thus symbolically crushing the enemy of Egypt beneath its weight. The face of the poor creature thus crushed, with the corners of his mouth drawn down, seems to express a mixture of hate and contempt. Whether this unique monument was made before or shortly after the unification of the Egyptian kingdom cannot be decided with certainty.

Museum Object Numbers: E1110 / E1114 / E4719 / E9665 / E1137 / E1136 / E1232 / E1147 / E1145

Image Numbers: 41455a, 41455b, 41455c, 41455d, 41455e, 41455f, 41455g

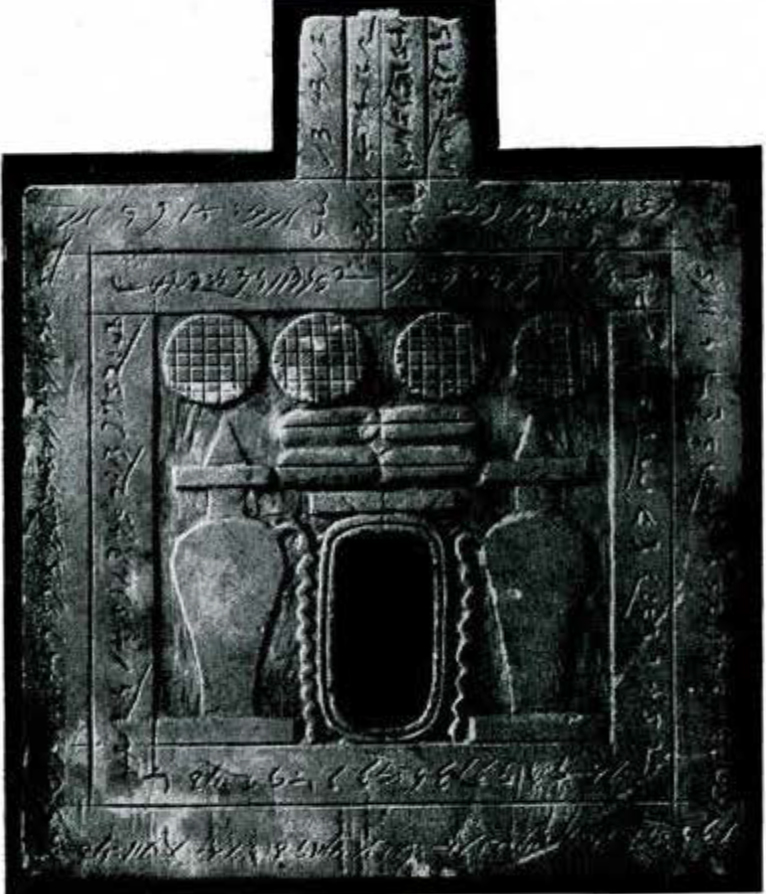

To our right is a large black granite slab, the tombstone of one of the 1st dynasty kings, from the cemetery at Abydos (fig. 15). It shows, in low relief, the king’s name, Kay-a, over a stylized entrance of the palace, and above it the falcon god Horus who was believed identical with the king himself. On both sides are small stelae of white limestone coming from surrounding tombs of the king’s retainers, servants and women. One belonged to the king’s favorite dwarf, named Ded.

To the right of the stelae is a huge alabaster jar (3958) which comes from the same temple as the door-socket. It has an incised inscription commemorating the victory of a 2nd dynasty king over Lower Egyptian rebels.

These early monuments are followed by others from the time of the pyramids. Among the objects which come from the so-called “mastabas,”1 the tombs of the Old Kingdom officials, are a limestone slab from Meydûm (32-42-53) bearing the name of a prince and a large flat diorite bowl (2250) with the name of King Snefru himself, incised and filled in with red; also a “false door” (fig. 16), through which the soul of the deceased was supposed to enter the offering chamber, and a number of lintels from Giza, some of them with excellently carved hieroglyphs. There are also three painted limestone statues representing some of these officials (fig. 17). The original colors are well preserved, and they all bear the name of their owner. None of them could be called the masterpiece of an artist; they represent rather the type of an Old Kingdom official than real portraits of different men. But besides their differing wigs-two wear the short, curly kind, one the long, straight kind-they differ in the treatment of the details of the head and bear witness to the high level that sculptural workmanship had attained in the second half of the Old Kingdom.

From the politically chaotic time which followed the Old Kingdom, the Museum has a great number of tombstones which were found during its excavations at Dendereh in Upper Egypt. The drawing of their reliefs and hieroglyphs is of the mediocre quality of that period. Characteristic is the small figure of a servant or a relative, drawn near the head of the tomb owner, which offers him or her the desired drink from a tiny bowl. Near these stelae, which are attached to the side walls, one (fig. 18) stands out as entirely different. It, too, is a tomb stela and it was made during the same general period, but while the Dendereh stones all have lost their colors, the colors of this one-black, red, blue and yellow-are excellently preserved, and the design, although still awkward, foreshadows the new strength of the second peak of Egyptian art which was reached in the Middle Kingdom. The owner, a high official from the Upper Egyptian town of Thinis, is shown surveying various gifts of food and drink, and added to this is a large menu listing individually various things enclosed in little square boxes, upon which the deceased could draw throughout eternity. The figures of his servants and those of the animals which they are leading-or trying to lead-toward him are very spirited and lively. Even the bodies of the killed fowl seem still to have life and motion.

Museum Object Numbers: E1545 / E1543 / E1539 / E1784 / E1424

Image Number: 41453

Museum Object Numbers: E1418 / E1416 / E1413 / E1412 / E1400 / E1408 / E4997 / E1399

Image Numbers: 41452a, 41452b

The period of the Middle Kingdom is represented by a few characteristic monuments, also from tombs. The limestone doorway of a tomb, rather narrow according to Egyptian usage, shows beautiful hieroglyphic inscriptions filled in with blue paste (9189). The text, giving the usual offering prayer for the tomb owner, begins in the center of the lintel and continues from that point across each side and down the vertical jambs. Instead of repeating the plant sign which should begin each inscription, the sculptor has carved only one sign and doubled the flower at the top, so that the sign may be read in either direction!

We have none of the typical tombstones of the Middle Kingdom with which other collections abound and which were inscribed on one face only, while the back was set into the tomb architecture. However, we do have an extremely unusual stone (fig. 19) which, although its inscriptions are similar to those otherwise found on Middle Kingdom tombstones, is inscribed on all four of its surfaces and also on the top. It must have been accessible from all sides and probably once stood within a temple. The incised hieroglyphs were filled with blue paste and their texts contain offering prayers for a large number of persons, probably all members of one family. Two limestone offering tables of the same time which definitely come from tombs give the names and titles of those for whom they were made (fig. 20).

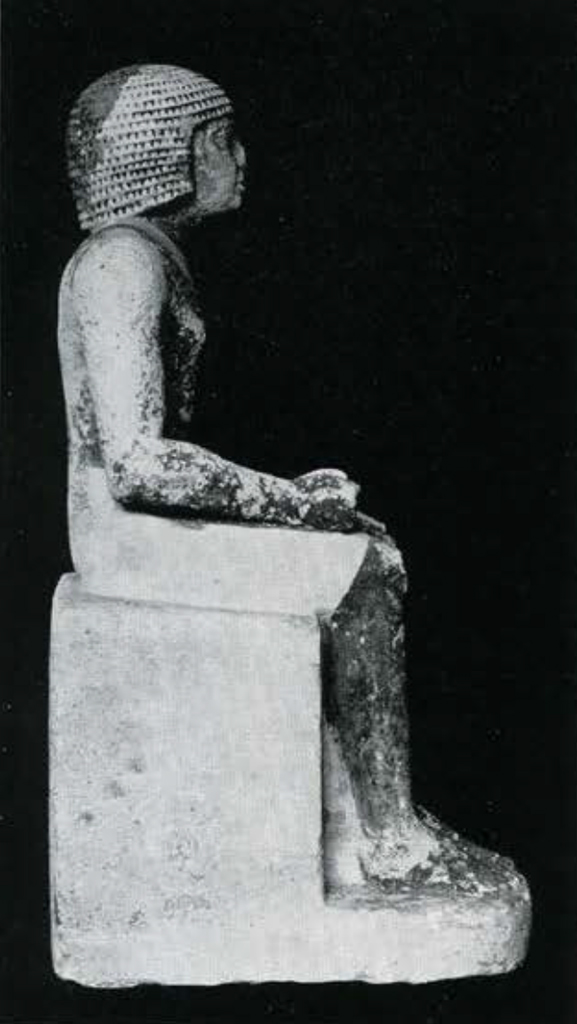

A seated limestone statue also belongs to the Middle Kingdom (fig. 21).2 It is remarkable in that it bears no inscription and does not come from a tomb but from the ruins of a house. Both these features concur to show that the statue never served the purpose for which it was made. This purpose, to keep the represented person alive throughout eternity, could only be achieved, according to the Egyptian belief, if the owner’s name was added by which he would be “kept alive.” The statue comes from the workshop of a sculptor, and a closer examination shows that its surface never received the last finishing touches. Probably it was broken in antiquity and the artist was unable to sell it to his customer.

Museum Object Numbers: E9510 / E6914 / E1326 / E1328 / E1338 / E1333 / E1324 / E1307 / E1371 / E1281 / E1363 / E15520 / E15501 / E16170 / E2276 / E2271 / E14174A / E14174B / E14170A / E14170B / E14171

Image Numbers: 32897a, 32897b, 32896b, 32896d, 32896e, 32896f

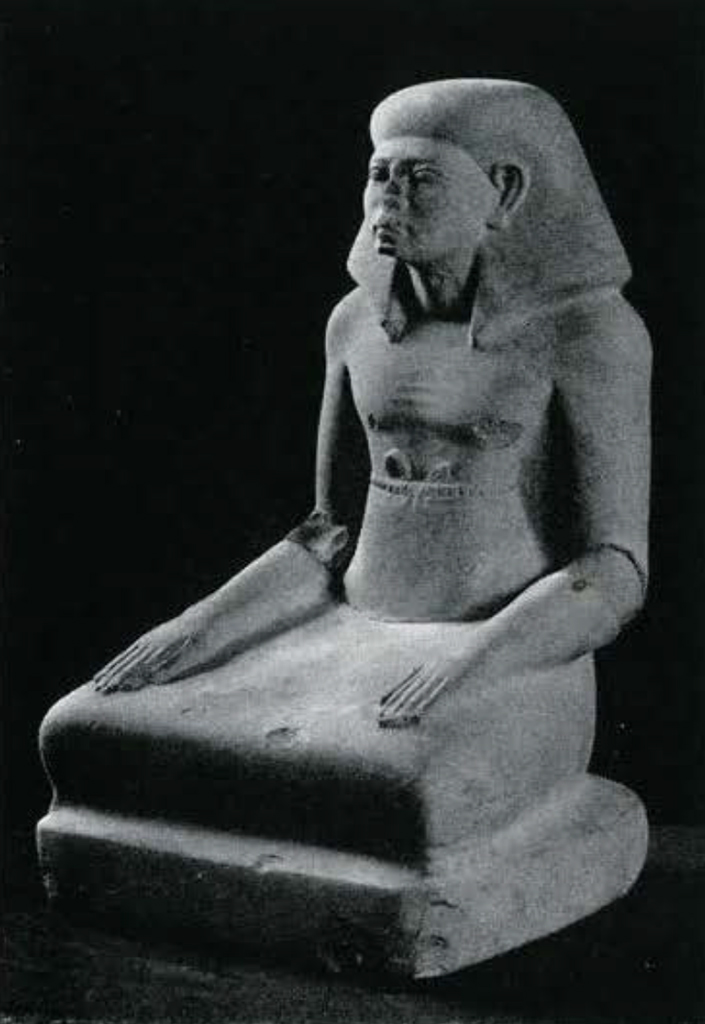

The Museum has a valuable example of New Kingdom sculpture dating from the beginning of the 18th dynasty. It shows a new type of Egyptian statuary which did not exist in the Old Kingdom and first appears during the Middle Kingdom. It is the statue (fig. 22) of a man who is squatting on the floor, with his knees raised up and his entire body enveloped in his long garment so that only the head and hands are visible. The life size figure, with a rather high base, is carved out of one block of grey sandstone. The idea of this posture seems to be that of leisure, as we so often find it today in Egypt as well as in other parts of the Orient. The man in whose tomb this statue was originally placed and whom it represents was a high functionary in the time of Queen Hatshepsut, named Sitepehu. His office was that of the highest priest in the Upper Egyptian district of Thinis, to which the sacred city of Abydos belonged. The inscription incised on his garment refers to his happy life after death, in the care of Onuris, the “god of gods,” who was worshipped at Thinis as the primaeval creator of the universe, and whom he had so faithfully served during his life. The red-brown color of the face and hands and the black of Sitepehu’s wig are remarkably well preserved, while the white of the garment has almost entirely disappeared. The blue paste which once filled the hieroglyphic signs and the red of the framing lines, today visible only in traces, must have given the statue a very colorful appearance.

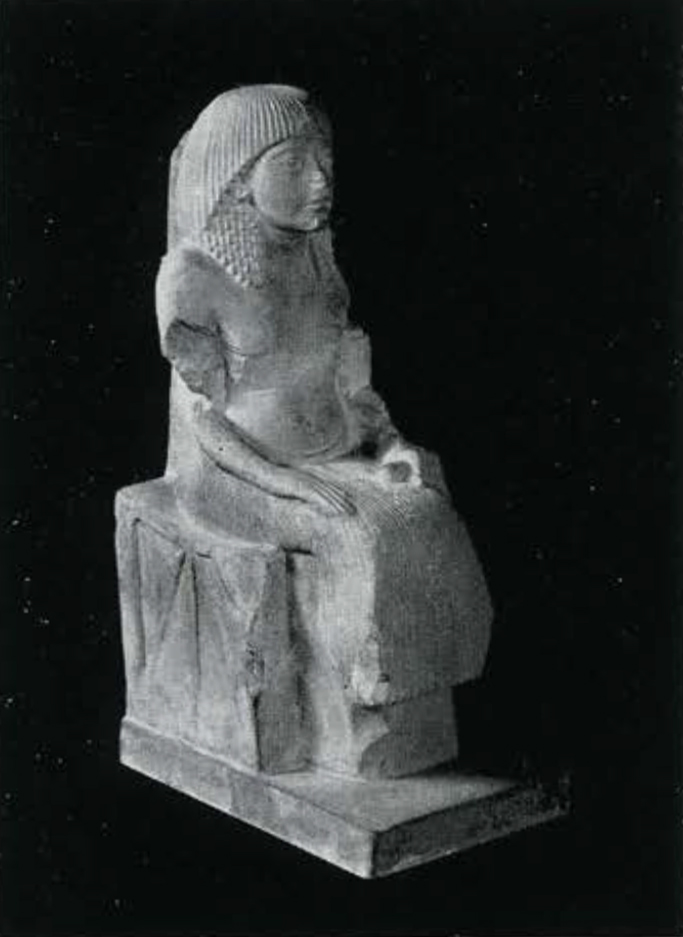

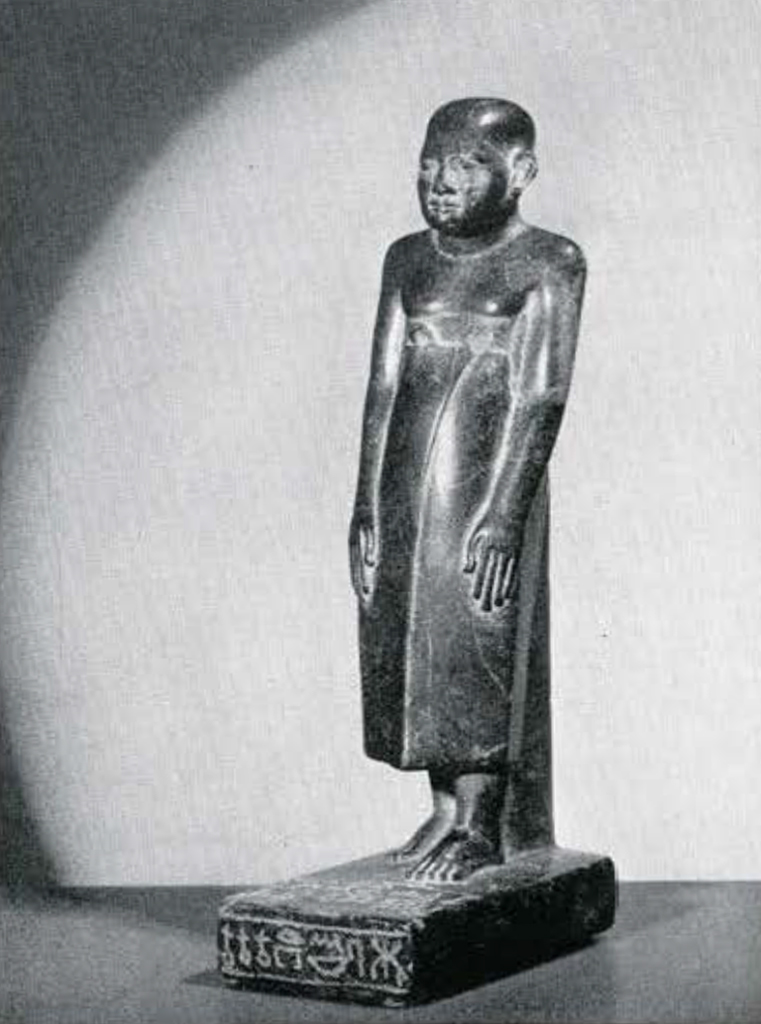

The small diorite statue of a seated scribe, with one knee raised (fig. 1) represents another contemporary of Queen Hatshepsut-Amenemhet, who was stationed at Buhen in the Nubian province. It probably stood in the local temple of the god Horus. His broad face and the shape of his nose and mouth seem to render traits more individual than those of the rather conventionalized head of Sitepehu. The statuette was found buried in the sand near the temple. It probably was hidden there by some friend of Amenemhet’s, when after the queen’s death the memory of her retainers was obliterated throughout Egypt and her provinces.3 Opposite this statue we see a head of dark grey granite (title page), wearing the royal headdress, which originally was decorated with an inlaid uraeus serpent, now missing. It shows perhaps the features of Hatshepsut herself. On the adjoining wall there is a limestone lintel which gives interesting evidence of the political situation after the queen’s death. It was originally inscribed with her name and that of her co-regent Thutmosis III, who followed her on the throne. But while the king’s names have been well preserved, those of Hatshepsut have been hacked out so ruthlessly that not a single sign can be recognized.

A sandstone portal (10987) from the Horus temple at Buhen, on the opposite wall, leads us back to the very beginning of the New Kingdom. Its inscriptions mention King Amosis, the expeller of the Hyksos, and the man who erected the portal and inserted his own figure on the inside of the left-hand jamb is known to us from other sources. While here he is simply called “commandant of Buhen,” he later was promoted to be governor of the whole Nubian province. King Amosis appears three times on the lintel, worshipping the falcon god Horus and Min, the god of fertility. In one scene he is accompanied by his mother Ahhotpe, the ancestress of the 18th dynasty.

Museum Object Numbers: E9369 / E6812A / E9406 / E9381 / E9403 / E9525 / E6853A / E9453B / E6880 / E9371A / E9395 / E9393 / E9394 / E6845E / E9591 / E9396

Image Numbers: 41446a, 41446b

Two tombstones of the 18th dynasty, on the same wall, are not without interest. One (29-87-462), dedicated to a priest Pa-ayar by his wife Idy, shows neatly carved hieroglyphs and relief figures. The other one (6783), rather crudely executed, is remarkable for the preservation of its colors. It was dedicated to a man by his brother, who is shown pouring water over a heavily laden offering table. On both these stones two large sacred eyes are incised, to ward off evil spirits.

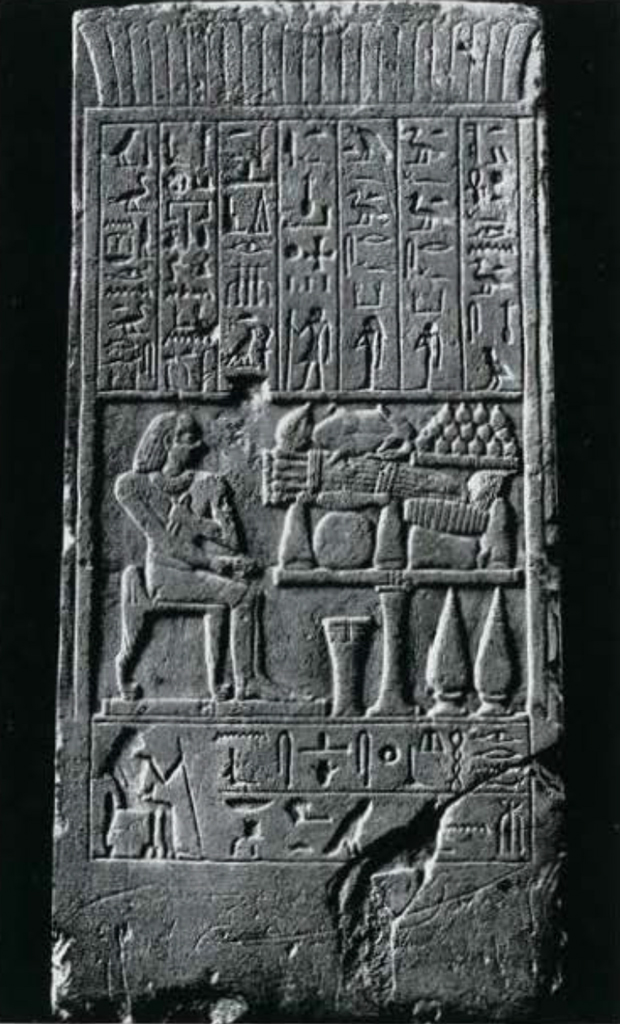

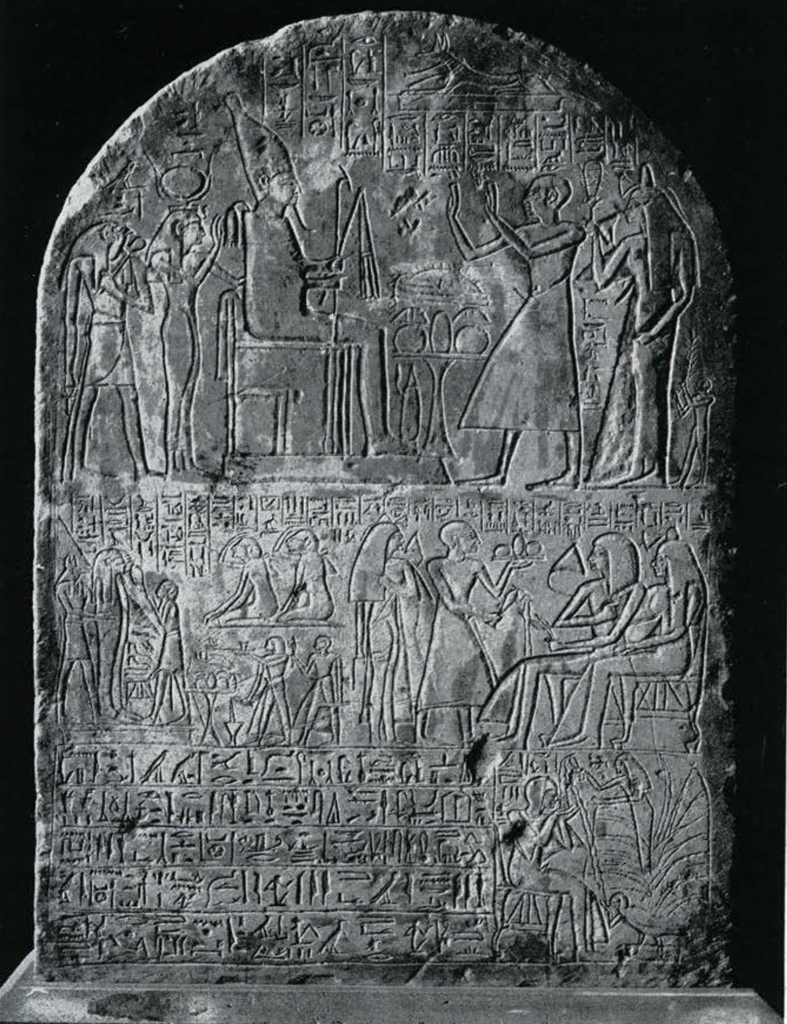

The large limestone stela (fig. 23) standing between these tombstones belongs, as the longer and more elaborate garments of its figures show, to the 19th dynasty.4 It has lost all its original colors but has a quite unusual variety of interesting reliefs. Its upper half is taken up by a scene of adoration. The tomb-owner, a priest called Shumay, stands worshipping before the enthroned mummy-shaped god Osiris, the ruler of the nether world. He is accompanied by his wife Baket-Ese, who raises a sistrum, the rattling instrument which was used by women in the cult of the temples. Her little naked son follows her, carrying a palm branch. Before Osiris an offering table is erected, the drawing of which seems to show that it was inserted as an afterthought. His wife Isis embraces him and is followed by her son, the falcon-headed god Horus. Her epithet ”mistress of the district of Thinis” proves that the stone comes from Abydos, the main cemetery of this district. The second great funerary god, Anubis, is represented by his sacred animal, a recumbent jackal. The lower half of the stela is covered with varied scenes. In its upper part, to the right, we find Shumay and his wife again. This time he presents a tray of bread and pours water for his parents Ramose and Meritre, who are seated in comfortable chairs. To the left are representations of funerary rites which were performed for Shumay. His mummy and his mummiform coffin are standing upright. A priest, wearing a leopard skin, performs with a special instrument the ritual of “opening the mouth,” by which the deceased was enabled to take food and drink and to speak again. A second priest, wearing the jackal mask of Anubis, supports the mummy. In front of this group two men offer incense and water, while above them two wailing women, belonging to Shumay’s household, are kneeling on the ground and tearing their hair or pouring dust on it. In the righthand corner, Shumay is shown once more, enjoying the results of the funerary rites depicted above. He sits in a chair in the shade of a sycamore tree and drinks the purest and coolest and sweetest water conceivable. This water is poured into his hands by the sky goddess Nut who is growing out of the sycamore. Shumay’s soul, a bird with human head and hands, is standing by, partaking of the much cherished refreshment. In the inscription, the funerary deities Osiris, Isis and Horus and the Upper Egyptian funerary god Wepwawet, who was especially attached to Abydos and here is called “ruler of the two lands,” are invoked for the deceased.

In the center of the Hall we see, seated on thrones, two over-life-size granite statues (fig. 3), of the lion-headed war goddess Sakhmet. They belong to the latest part of the 18th dynasty and probably once stood in the court of one of the temples of Amenophis III. The white lines indicate which parts of the statues have been restored.

Museum Object Numbers: E6862 / E6854 / E9556 / E6881 / E6865 / E9594 / E9380 / E9368 / E3844 / E3843

Image Number: 41449a, 41449b, 41449c, 41449d, 41449e

Museum Object Numbers: E4897 / E4899 / E4903 / E4895 / E4896 / E4894 / E4902 / E4900 / E4898 / E11522

Image Number: 41448a, 41448b

Behind them, three animal figures dating from different periods have been placed together. One of them is a painted limestone figure of uncertain identity (fig. 24). It probably represents a dog, as the collar around his neck and the whole execution of the body would suggest, but he also seems to have a mane, and this would suggest a lion. Perhaps it was intended to represent some fabulous beast. The purpose which such a figure might have served is not known, nor do there seem to be similar pieces in other Egyptian collections. The royal name painted on the animal’s breast seems to point to the 21st dynasty.

The second figure is an excellently carved basalt baboon (14366), the sacred animal of the god Thot of Hermopolis. His raised arms are broken off, but from similar representations we know that he was shown worshipping the rising sun. On his chest is an elaborate pectoral with the name of one of the later kings of the New Kingdom who is called “beloved of Thot.” An inscription on his back was addressed by Thot to “his beloved son, the lord of the two lands, . . .” This statue, with similar ones, possibly stood above a temple entrance, as they did in front of Rameses II’s rock temple at Abu Simbel in Nubia.

The third is the large and beautifully executed bronze figure of a cat (fig. 4), sacred animal of the goddess Bastet. She was worshipped especially by the rulers of the 22nd dynasty who resided at Bubastis in the Delta.

We shall now follow the objects exhibited on the northern and southern walls.

Museum Object Number: E3959

Image Number: 31056

The Northern Wall.

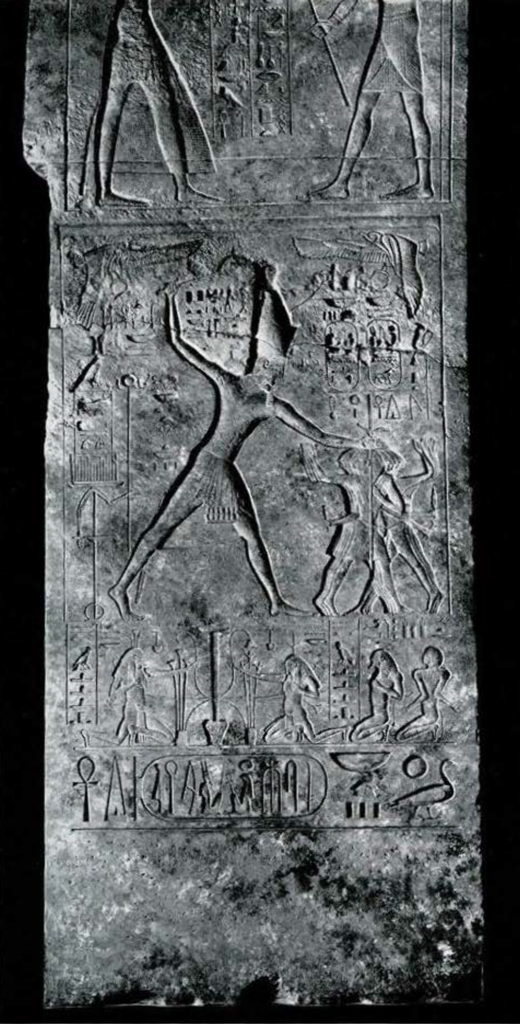

A very deeply cut relief from the wall of a temple at Tell-er-Retabeh the Eastern Delta (fig. 2) is an example of one of the most frequently repeated representations-Pharaoh slaying an enemy-which is known from the beginning of Egyptian history. In this case it is King Rameses II who, striding out vigorously, hurls his weapon down upon the head of a kneeling Syrian whom he grasps by a tuft of hair. The bearded Semite, turning away his head, raises his arms in vain to ask for mercy. In front of the king stands the god Atum who offers him a weapon and gives him “all power and all strength.” Beside the king’s usual name which is enclosed in an oval, we notice on either side of the group and effectively framing it, his ceremonial “Horus-name”: “The strong bull, beloved of Ma’at” (the goddess of righteousness).

A small stela (17518) with rather crudely executed reliefs and inscriptions comes from a sanctuary in the lake district of the Fayyûm, where King Thutmosis III, the great conqueror of the Egyptian province in Asia, was worshipped. The deified king, holding crook and flail, the emblems of Osiris, is seated on a throne. On a high stand before him is a ewer adorned with a papyrus stem. Opposite him stands the dedicator of the stela, an official called Wasmuare-em-hab, who is clad in the modish garb of the later New Kingdom. He has a bouquet of papyrus in one hand and raises the other in prayer to King Thutmosis, “the great god,” asking him for “life, prosperity and health.”

A high rectangular offering table of rose granite (15413) once stood in the tomb of a vizier Rahetpe who, as we know from another monument, served under Rameses II as an ambassador to the king of the Hittites in Asia Minor. Some of the desired food offerings mentioned in the inscription-baskets with fruit, loaves of bread, head, joints and ribs of an ox-are shown in relief.

Museum Object Number: E6878

Image Number: 31342

The figure of a male deity, painted on Nile mud, may come from one of the small sanctuaries of the 20th dynasty in the workmen’s village at Deir-el Medineh opposite Luxor.

Next is the partly restored lid of a mummiform coffin of grey granite (15415), originally made for an official under King Amenophis II, Paser, who was “follower of the king to all countries.” The well-carved head is a good piece of work of the early 18th dynasty. Paser wears a short beard, a long wig, and a broad collar around his neck. In his crossed hands he holds the symbols of the funerary deities, Osiris and Isis. Below them is seen the figure of a falcon without spread wings. The coffin did not rest in Paser’s tomb for very long. It was usurped, probably in the 19th dynasty, by a military officer Pakhamnate, whose name appears at the foot and who was buried near Sedment, Upper Egypt.

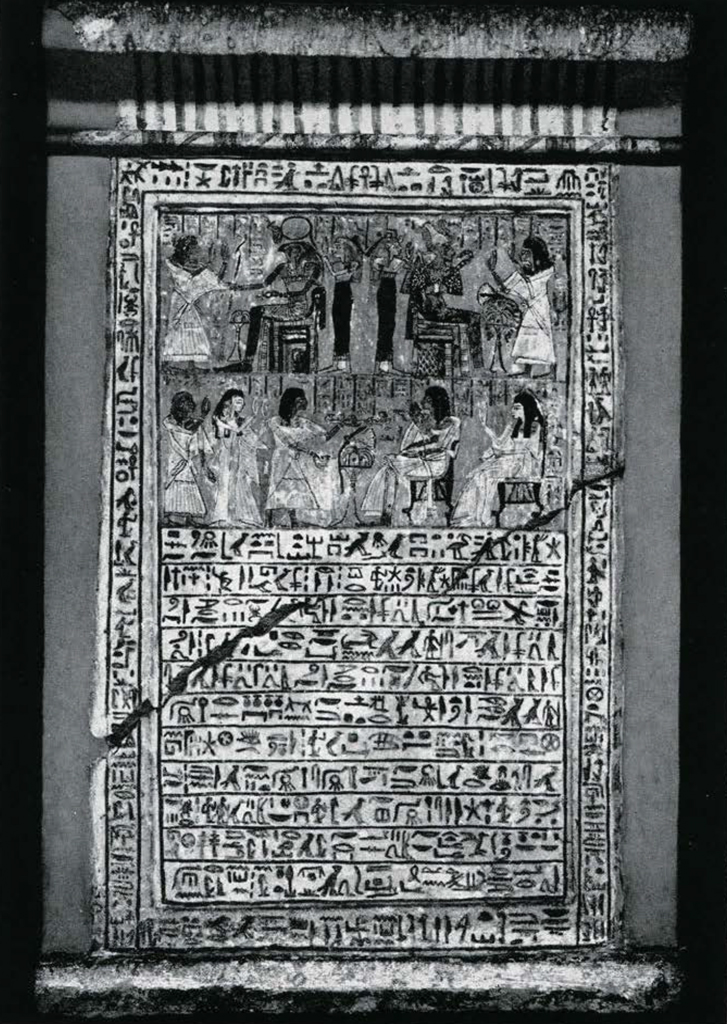

One of the showiest pieces in our collection is a large ”false door” stela of sandstone (fig. 25). It belonged to the tomb of a man called Mery, who at the time of the 20th dynasty was superintendent of the Egyptian treasury in Nubia and lived at Anibeh. This high official had, according to the custom then followed by well-to-do Egyptian residents in Nubia, built for himself a tomb in the form of a small brick pyramid. This stone was erected in front of the pyramid, where it was accessible to the visitors of the cemetery. Its surface shows two panels of sunk relief. In the upper row we see Mery worshipping Osiris and Isis (right) and the falcon-headed sun god Re-Harakhte, accompanied by Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice with the hieroglyph of a feather on her head (left). In the lower row, seated on ebony chairs, are Mery and his wife Tawere-herty, who was a musician in the temple of Amon-Re of Karnak. They are approached by three relatives. The first man, Paneb, probably the eldest son of the couple, pours water in front of an offering table and holds an elaborate censer; the other two raise their hands in prayer. The colors-blue, red, black and white, vividly standing out from a yellowish brown background-are remarkably well preserved, but the style of the reliefs and inscriptions accompanying them is provincial and they are rather clumsily executed. The long inscription below, painted in blue with red dividing lines, begins with a hymn to the sun god, which contains a partly misunderstood crude mixture of religious texts. The entire stela is framed by inscriptions containing prayers for the deceased.

Museum Object Number: E14318

Image Number: 31231

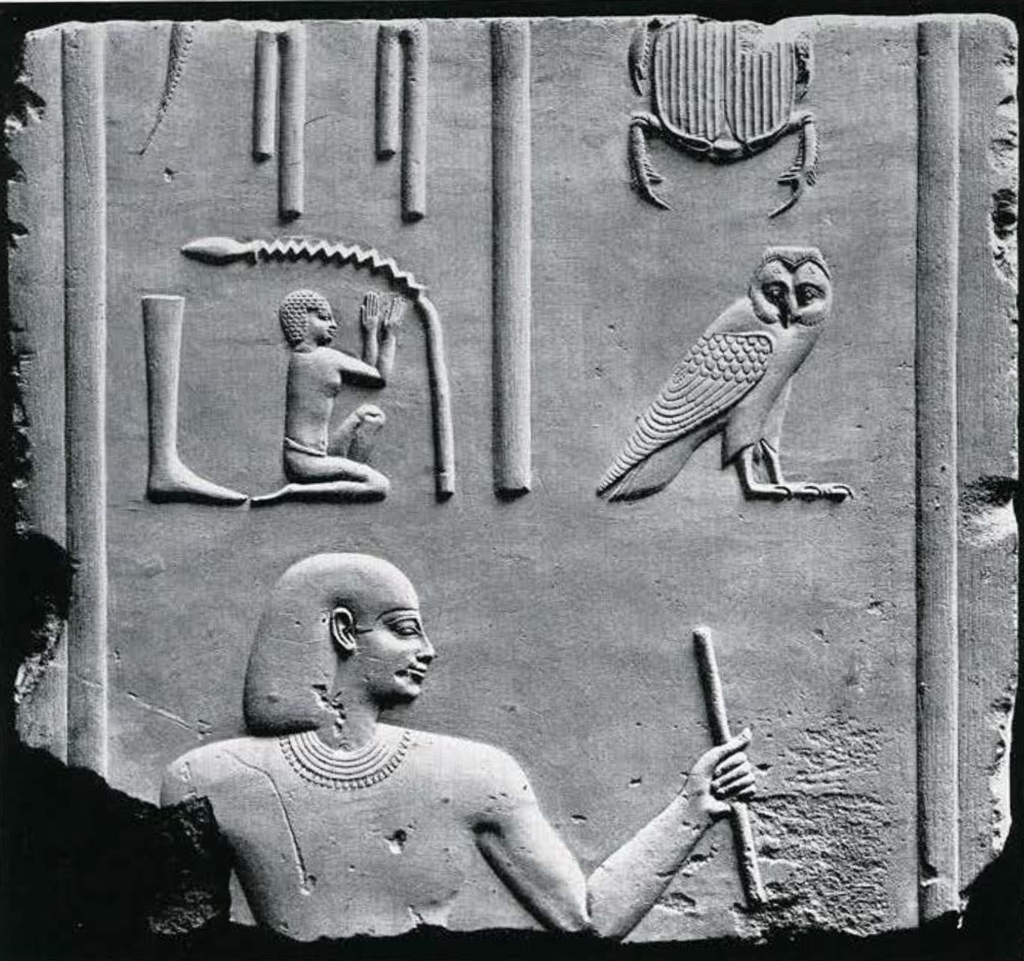

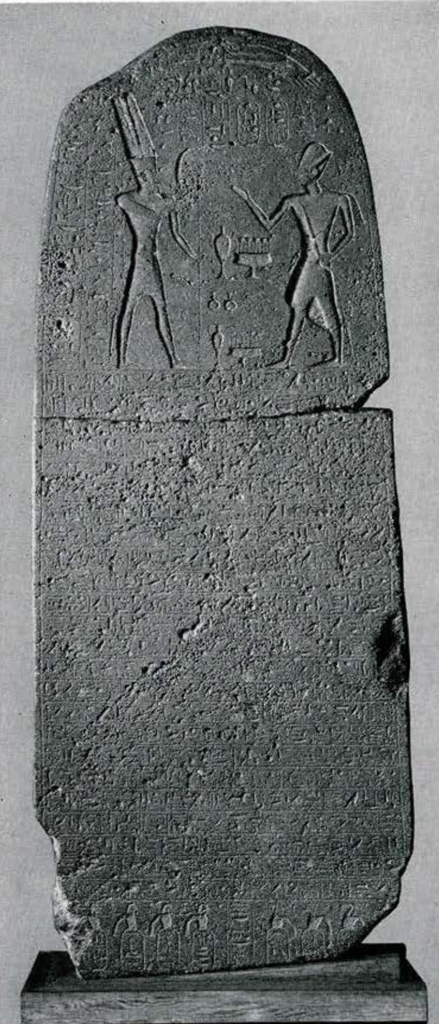

This false door is followed by a large limestone lintel (fig. 26) of the time of the 21st dynasty, after the unity of the New Kingdom had been lost. The building from which it came was a temple, probably in the district of Memphis; for the priest of Amon-Re, Enkhefnemut, who had the lintel inscribed, is called a scribe in the temple of the Memphitic god Ptah. It was erected under a King Si-Amon, of whom only a few monuments are known. The kneeling figure of the priest is repeated on the right and left with shaven head, a large fan in one hand, while the other is raised in adoration of the king’s names which fill the center. The reliefs and hieroglyphs still show the good tradition of the art of the New Kingdom.

The limestone head of a lioness (fig. 28) concludes on this wall the monuments of the New Kingdom. It is excellently carved in the best style of the 18th dynasty. It was found at Gurob, near the entrance to the Fayyum. Unfortunately no other details are known which might shed light on its original use. It must, however, have belonged in an architectural context and may have been part of a balustrade or of a dwarf wall terminal.

The Southern Wall.

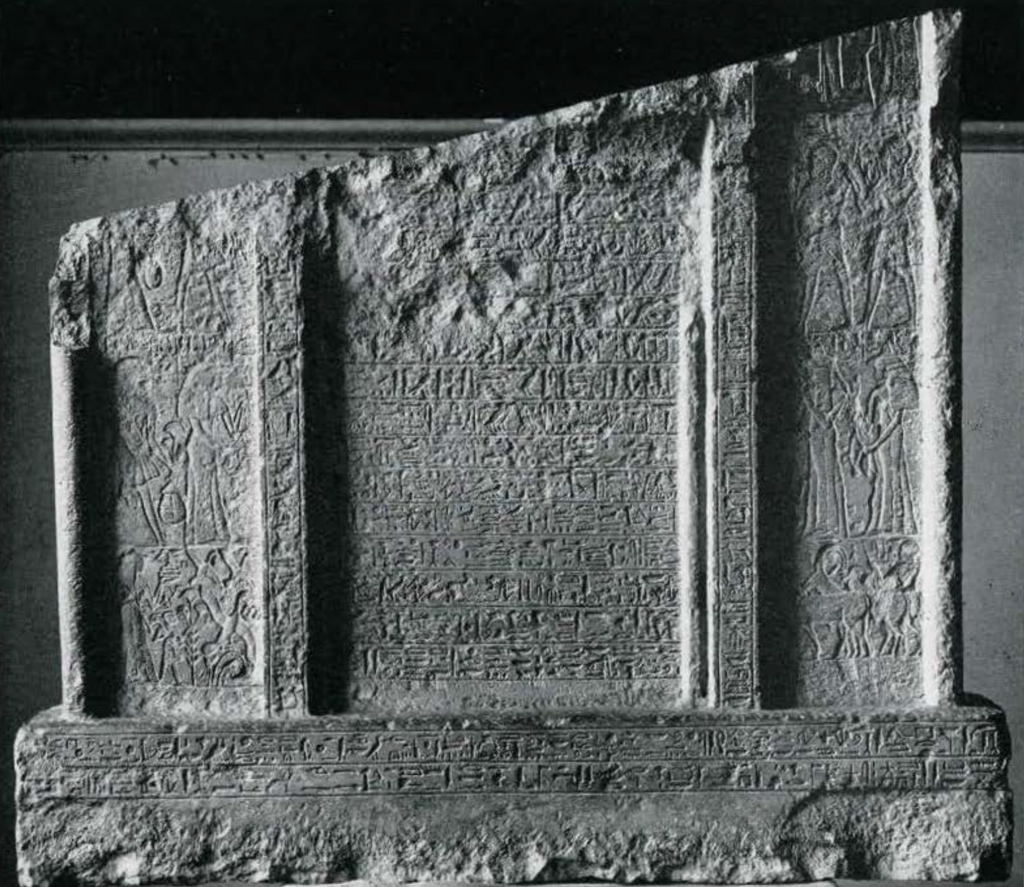

The lower part of a large limestone stela of the 18th dynasty (fig. 27) comes from the cemetery near Sedment in Upper Egypt and belonged to the tomb of a man called Amenemhet. He was a priest of Harsaphes, the chief god of the district of Herakleopolis. The pleasing execution of the incised reliefs and hieroglyphs of his tombstone show that he employed a very able and unusually imaginative sculptor. The stone is divided into three sections. A center part, bearing the remains of a long inscription, is separated by inscribed projecting pillars from two narrower side sections which are covered with reliefs and end in round half. columns. A high, broad base, with two lines of inscription, projects slightly on either side. In the central inscription, which assures the deceased of a long life in the hereafter, the god Harsaphes has the unusual epithets “king of heaven, ruler of the stars.”

Museum Object Number: E2551

Image Number: 31086

The charming reliefs on the sides show several of Amenemhet’s sons and daughters who bring him gifts of food and bouquets of flowers. The pictures in the lowest register are quite unusual. On the left side, a woman and a boy carrying similar gifts have been placed in a landscape with flying ducks. The differences in the size of these ducks- the one in the foreground is much larger than those in the background-is quite surprising and seems without parallel. On the right side, a herdsman is leading an ibex and two calves. The posture and movements of the animals are very gracefully depicted. The upper part of the fragment is badly defaced. Only the top register on the right-hand side, on which an enthroned god was represented, shows the original brown color of the surface.

The two upper parts of a limestone door jamb (1828, 1829), with four columns of large incised hieroglyphs, once formed part of the stately entrance that led to a tomb situated near the Ramesseum at Thebes. This tomb belonged to a man called Harsiese who bears the ancient titles of Egyptian nobility. He was “superintendent of the treasury” under the 22nd dynasty and also priest of the god Sokaris in the temple of Karnak. He must have been a personal favorite of the king, for he “knew the secrets in the palace,” and he calls himself “the ears of the ruler” and “the companion of the lord of the two lands.” The signs of the inscription and the lines dividing the columns were filled out with dark blue paste, most of which is excellently preserved. The texts, besides name and titles, contain wishes for his arrival in the nether world. Proud of his family, Harsiese mentioned not only the name of his father Nakht-tefmut, who held the same office, but also one or more other ancestors whose names are lost.

A block of sandstone with brilliantly executed figures of the Horus falcon and uraeus serpents, and with parts of an inscription outlined in red, must come from another part of Harsiese’s tomb, the decoration of which remained unfinished. A fragment with a painted inscription and the charming, slender body of a young girl, most gracefully drawn, comes from the same place and perhaps belonged to Harsiese’s tomb also.

Museum Object Number: 40-19-1

Image Number: 31269

The following four painted slabs of sandstone also come from the tombs of the 22nd dynasty near the Ramesseum. In all of them the colors of figures and hieroglyphs are beautifully preserved.

The first two slabs and the fourth (1824–1826) belonged to the tomb of a lady called Djemutesonkh, who was the daughter of a “fourth priest of Amon” in Karnak, named Nakht-tefmut. They all contain scenes connected with the funerary rites.

On the first slab we see the lady, clad in a transparent garment of white linen, the upper part of which appears to be stained by the melting cone of unguents on her head. She is facing toward the left where the goddess of the West was shown performing a ritual act. To the right, the prow of a sacred boat is visible, standing under a canopy and resting on a support which is decorated with a papyrus-bouquet. In the upper part the sun god, with the sign of life in his hand, is accompanied by three other deities. He stands in his boat, in which he crosses the subterranean waters at night.

On the second slab, Djemutesonkh, clad as before, is being purified by a priest who wears a leopard skin.

The fourth slab shows a beautiful picture of the goddess Isis-Hathor, crowned with a large sun disk and the horns of her sacred animal, the cow. Her hands are raised as if in prayer.

Museum Object Number: E16012

Image Number: 31236

The third slab (1827). painted in very different colors, comes from another tomb. Its owner, a high priest of Ptah, is seen twice, clad in a leopard skin and with the elaborate collar of his office around his neck, kneeling in front of two standing deities who present him with signs of life. The left one is mostly destroyed. To the right is the sun god Atum wearing the crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. In the center we notice the façade of a shrine. The light pink color of the priest’s body is remarkably different from the dark red color that usually is shown.

In the central part of the Hall, between the walls just described, we find first two small pieces of statuary. To the right is the limestone figure of a seated man called Maimua (fig. 29). It dates from the early 19th dynasty and was found in his tomb during the Museum’s excavations on the western side of Thebes. If we look at the statue more closely, we see that it is only one half of a group, but all that remains of the wife who sat to the left of her husband is one hand resting on his right shoulder. Her name has been destroyed with her body. Maimua wears the pleated longish kilt of the period and an elaborately curled wig which frames his head and neck. The inscription on his kilt requests that Maimua, who was an official in the temple of Karnak, take part in the offerings given to Amon. It also wishes him “a good life in Thebes.” On the back pillar, offering formulae were addressed to different funerary gods. On Maimua’s breast the name of the god Amon is incised. The sculptor’s work is of good artistic quality.

The counterpart to the left is a steatite statuette of the great god Amon himself, an excellent piece of art that probably belongs to the late 18th dynasty (fig. 30). The god appears clad in a loincloth of peculiar form. A broad collar of precious beads is around his neck, bracelets are on his wrists. He wears a long carefully braided artificial beard which is fastened behind his ears by thin straps. The two high feathers which surmounted his cap are broken off. In his hands he holds symbolic signs of protection (?). Faint traces of an original gold leaf covering are discernible. The statuette probably once stood in a temple, possibly dedicated by a worshipper whose name, together with the feet of the god and the pedestal, has been lost.

Museum Object Number: E15414

Image Number: 31328

In the center, back of these two statuettes, rises the impressive colossal statue of an enthroned Pharaoh, carved of a brownish quartzite (635). In spite of the numerous inscriptions which cover its high pedestal and the sides and back of the throne, we are unable to say which of the Egyptian kings was represented. For it is obvious that these inscriptions were done later, after the surface with the original inscriptions had been chiselled off. The king who usurped this earlier statue for himself, as he frequently usurped other monuments, was Rameses II, the renowned ruler of the 19th dynasty, who held the Egyptian throne for 62 years. The statue comes from the temple of the god Harsaphes at Heracleopolis, to which also belonged the great granite column exhibited in the Lower Hall. Heracleopolis was the residence of the kings of the 9th dynasty, between the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but it is very unlikely that our statue was made for one of them, since we know of no monumental objects of their time. More probably it represented one of the great builder kings of the Middle Kingdom, but it is impossible to attribute it to any one of them with certainty. Whoever he may have been, the king is shown in the typical royal dress of the Old and Middle Kingdoms: a short kilt fastened by a belt from which a lion’s tail (seen between the legs) hangs down behind, and the striped headdress, whose coloring is still discernible. The sacred uraeus serpent rises on his forehead to spew its venom against possible aggressors. The long artificial beard and parts of the arms are missing.

The deeply cut inscriptions which repeat Rameses II’s name and titles and call him “beloved of Harsaphes” (the god is pictured with the head of his sacred animal, the ram) were filled in with red paste. On the left side of the throne, a mistake of the sculptor who cut the hieroglyphs had been corrected, but the plaster once covering it has fallen out. The result is that we see the sign of a duck with two tails and four feet and a sun disk in place of its head!

Behind this colossus is a life-size standing figure of Rameses III (fig. 31),the last great ruler of the New Kingdom. It is carved of limestone which now has a brownish color. The king wears a pleated kilt, a collar, bracelets, and an elaborate wig with the uraeus in front. A dagger, adorned with falcon heads and sun disks, is thrust through his belt. In his left arm he holds a ceremonial staff, crowned with a lion’s head. It symbolizes the war goddess Sakhmet whose enthroned statues we have seen earlier. The mediocre workmanship of the statue and of the broad features of the king’s face are characteristic of the average sculptural production of this time. The inscriptions are very clumsily incised. On breast, belt and back, they give the king’s names and titulary. Twice he is called “great of jubilees,” and it seems not impossible that the statue, whose origin is unknown, was placed in a temple at one of the king’s jubilee festivals. The high crown which the king wore, and with it the upper part of the back pillar, is missing. The same is true of the lower part of the figure from the knees downward. On the left side of the statue, the “great royal consort” is shown in low relief, wearing a tall crown and raising her right hand. Only the upper part of this relief is preserved.

The easternmost part of the Hall is reserved for a few objects from the latest period of Egyptian history.

Museum Object Number: E253

Image Number: 31065

Museum Object Number: E9217

Image Number: 32891

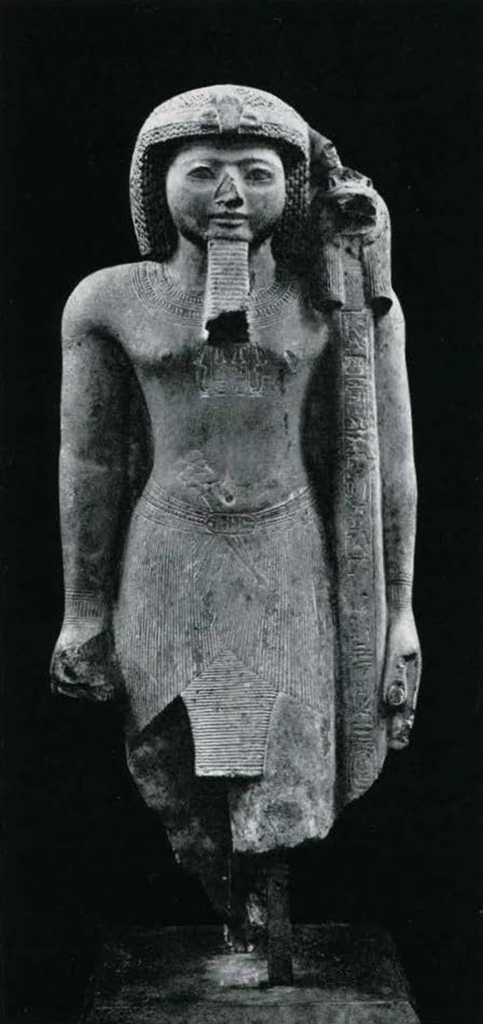

Of these, the most valuable piece is the kneeling statue of a contemporary of Amasis, the last king of the 26th or “Saïte” dynasty.5 The man here represented (fig. 32), by the name of Psamtik-si-Neith, is kneeling on a high pedestal and holds between his outstretched hands a shrine which has a peculiarly shaped support and contains a statuette of the god Osiris. The whole statue with the base, including the shrine, is carved out of a single block of very hard black basalt. It is a typical example of the sophisticated work of the Saïtic artists who tried to restore by their technical skill the bygone times of the Old and Middle Kingdoms without being able to regain their force and vitality. Note the smooth and rather academic treatment of the body and the superior mastery over the stone. The well-carved inscriptions which cover the shrine with its support and the upper part of the base contain prayers to Neith, the patron goddess of the Saïtic kings. They allude, rather vaguely, to the political disturbances of the time. King Amasis, the friend of the Greeks, who by this time had established extensive colonies in Lower Egypt, was a usurper of the Egyptian throne. Psamtik-si-Neith, who was “leader of all the building work” in Saïs and at the same time held priestly offices in the great temple of the royal residence, seems to have been a favorite and powerful partisan of the king. The statue stood, as the inscription says, in the inner sanctuary of the temple of Neith at Saïs.

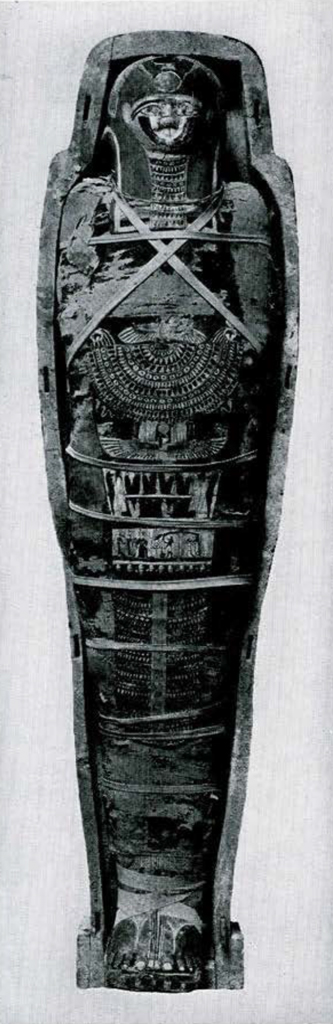

To about the same time belong a stone sarcophagus and two lids of stone sarcophagi, all of them mummy-shaped, which are set up along the walls.

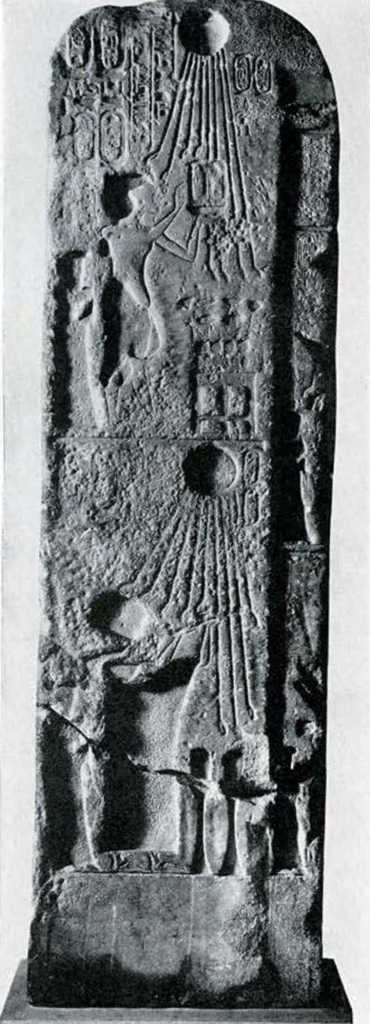

The sarcophagus, which is carved of a hard greyish limestone (16135), belonged to a priest called Petebast. Lid and box are covered with long incised hieroglyphic inscriptions containing funerary texts for the benefit of the priest. Those on the lid are surrounded, above and on the sides, by incised reliefs. In the center of the top row, the sun disk, with its rays descending, is worshipped by the goddesses Isis (left) and Nephthys. They are followed on either side by a representation of the priest’s soul-a bird with shaven human head-standing on a high pedestal and raising one human arm in adoration. Behind them a group of eight standing deities is seen, holding strips of linen mummy bandages in their hands. Some of them are characterized as belonging to the four “Sons of Horus,” under whose care the viscera of the deceased were placed (see Mummy Room, Cases 4 and 5). In the second row, the center is occupied by the sacred symbol of Osiris, flanked by the figures of sixteen standing deities or demons with their names written above them. On either side, three figures of bird-headed demons (1 falcon, 2 ibis) are presenting a sail, the symbol of the breath of life. They are followed by figures of the goddesses Isis (left) and Nephthys, the wives of Osiris.

Museum Object Number: 40-19-2

Image Number: 31271

One of the coffin lids (16133), of white limestone, has only one incised column of hieroglyphs. It contains a prayer to Osiris, “the leader of the Westerners,” for a man called Hapimen, who held several priestly offices. He was a “third priest” of the goddess Mut and also a priest of Horus. The mummy of Hapimen, which had been buried in this coffin, together with that of his pet dog, is on exhibition in the Mummy Room (p. 88). The stone coffin to which this lid belongs was placed within a large rectangular stone sarcophagus in the man’s tomb in the cemetery of Abydos.

The other lid (16134) is carved from two pieces of black basalt; the lower end is restored. The broad, battered face looks rather barbaric. Two columns of hieroglyphs are neatly incised on the upper part of the body. They tell us that the man once buried in this coffin, who commends himself to Osiris and Mahesa, was a military commander named Putumhese. Surmounting the inscription is the hieroglyph for the sky, studded with stars.

Against the north wall is a limestone stela (15994) with crudely executed reliefs and inscriptions which may be of somewhat earlier date. Below the winged sun disk, with its two pendent uraeus serpents, and the sign of the sky, we see a woman clad in a long diaphanous linen garment standing in adoration before the deities Re-Harakhte, Atum, Isis, and Nephthys. The inscription gives her name as Irti-erow, the daughter of a priest and scribe, Khenserdes, and of a woman called Esekhebye.

Museum Object Number: E14306

Image Number: 41457

A broad lintel of brownish sandstone (14317), painted and gilded, belongs to the 29th (the last but one) Egyptian dynasty, whose monuments are rarely found outside of Egypt. It comes from a temple which King Akoris built at Thebes and shows, in lightly sunk relief, this king in the company of various deities. On the left-hand side the god Amon is enthroned; behind him stands his consort, the goddess Mut of Asher, with the double crown on her head. The lion-headed goddess Sakhmet, rattling two sistra, approaches them. She is followed by the king, who wears the crown of Upper Egypt and offers a symbol of Ma’at, the goddess of truth and justice. Further to the left we see the king once more, this time wearing the double crown and introduced to Amon by the falcon-headed god Month. On the right hand side, the figure of Akoris, here wearing the crown of Lower Egypt, is repeated. Preceded by the district goddess of Thebes, he offers wine in globular vases to the enthroned falcon-headed moon god Khons-em-wese-Neferhotep (who at Thebes was worshipped as the son of Amon and Mut) and the goddess Hathor. Behind the king are the remains of a figure of a male deity “leading the king into the temple.” The reliefs and hieroglyphs, rather clumsily executed, testify to the decay of Egyptian art. Some parts of the reliefs have been restored.

From the time when the Ptolemies, the successors of Alexander the Great, ruled over Egypt, we find the following monuments:

- Three fragments of relief (221–223) come from a temple of Hathor erected in the Western Delta by Ptolemy I, whose head is seen on the right fragment. The name Ptolemaios (Ptolemy), which played a role in the decipherment of the hieroglyphs, is seen enclosed in an oval on the two remaining fragments. On the lower fragment, the drawing of the toes seen from the outside betrays the influence of Greek art.

- The quartz head of a life-size royal statue (14303), wearing a helmet-like crown with the uraeus serpent, is of rather good workmanship.

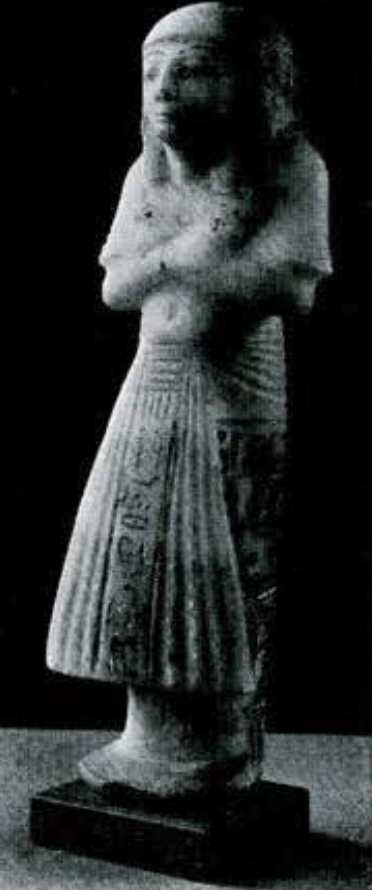

- The life-size standing figure (fig. 33) of a woman wears a pleated garment and above it a shawl decorated with fringes.6 (The origin of this sort of garment, which is not Egyptian, has not yet been ascertained.) In her left hand she holds a bunch of flowers. The long inscription incised on the back pillar mentions a high official with a great number of military and priestly titles, who requests the priests of Hathor at Dendereh to keep his name alive in the temple. In a ceremonial answer, the “princes and priests of Dendereh” wish him a life of 110 years and that he be succeeded by his descendants. If a lacuna in the text has been restored correctly, the figure represents the goddess Hathor of Dendereh and was dedicated by the official, whose name is lost. The statue, of hard grey granite, is a remarkable piece of art dating from the end of the Ptolemaic period. The rendering of the folds of the lower garment seems to be influenced by Greek feeling. The head is missing.

- Finally, there is a limestone offering table (32-42-749) with neatly designed reliefs which show a wooden stand surmounted by slender vases (?) and rosettes. Libation water runs from two tall vases into depressions carved in the shape of royal name rings. The piece, which was found by the Museum’s expedition to Meydûm, has no inscriptions.

Museum Object Number: E11367

Image Number: 32900

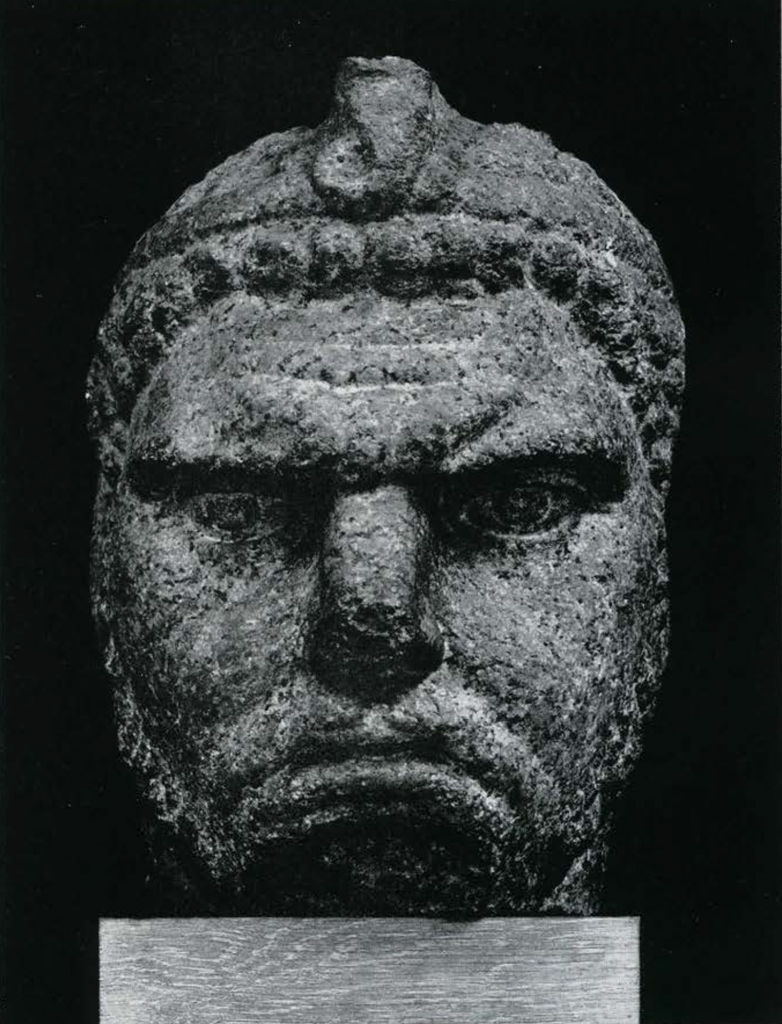

In the center of the east wall of the Gallery, there is another outstanding piece of art, but very different from the Ptolemaic goddess. It is the head of a colossal granite statue of the Roman emperor Caracalla (fig. 34) which once stood at the entrance to the temple of the goddess Isis at Koptos. Its features, the deepset eyes, the brutal heavy mouth, the forehead with its wrinkles, the curled hair and beard, have nothing to do with the traditions of Egyptian art. But the Roman sculptor who fashioned the statue has given it a genuine Egyptian back pillar, and in front of the fillet that encircles the Emperor’s head he added, according to most ancient Egyptian custom, the rising uraeus-serpent-thus indicating that Caracalla was represented here as king of Egypt.

Another representation of the Roman period in Egypt is a statue of brownish sandstone, a little under lifesize (975). It comes from the temple of Min, the god of fertility, at Koptos and shows a man dressed in a garment very similar to that of the Ptolemaic statue from Dendereh. He wears a band of rosettes in his curly hair and holds the edge of his fringed robe.

The Nubian Room.

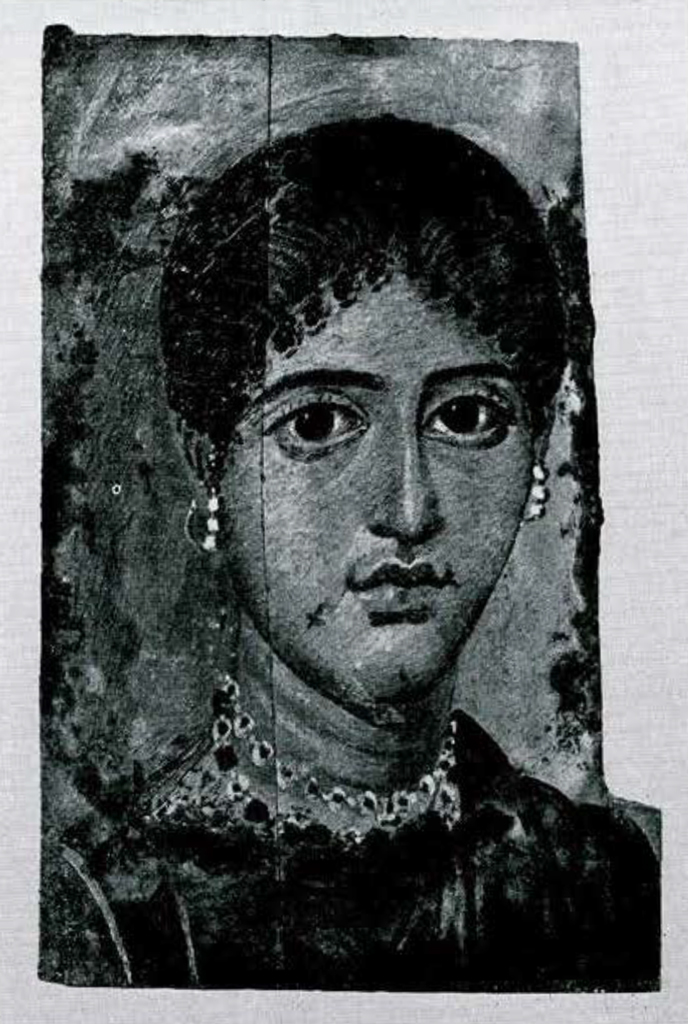

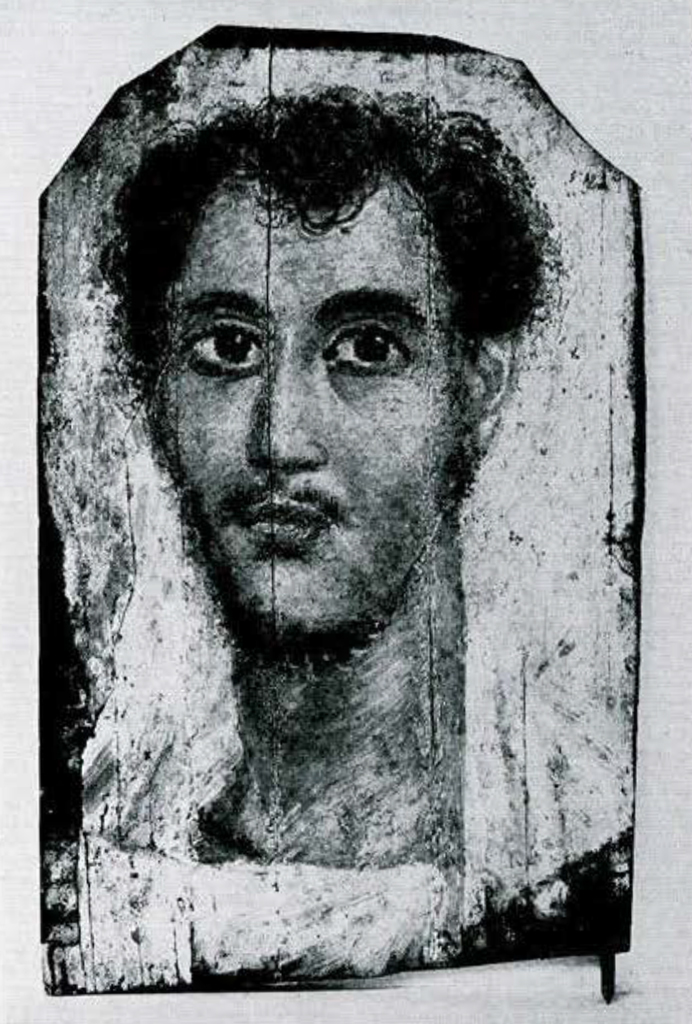

Having thus reached the end of the Hall of Statuary, we enter the side room to the southeast, where once more we find ourselves in the atmosphere of the Roman period. These objects, however, do not come from Egypt proper but from excavations of the University Museum at four different sites in Lower Nubia: Areika, Anibeh, Karanog, and Buhen.

Museum Object Number: E14345

Image Number: 31306

We first notice two rows of stones, set up along the western and eastern walls. The majority of them have the typical form of the Egyptian offering table as we found it in the Hall of Statuary: a rectangle on which the food offerings were placed, usually with reliefs surrounded by inscriptions, and a projection with a depression into which a liquid could be poured. These tablets were placed flat on the ground in front of the tombs. Their reliefs show, often in a very crude fashion, the ancient patterns of bread, jars and flowers (fig. 35). We even find the basin in the form of the cartouche still in use. An exceptional offering table shows the jackal-headed god Anubis and a goddess standing on either side of a vase (?). In another case we see what appears to be two bunches of grapes on either side of a strangely stylized tree or column. The inscriptions are not in hieroglyphs but have a cursive form reminiscent of shorthand called “Meroitic,” after the town of Meroe, which from 300 B.C. until ca. A.D. 350 was the capital of an independent Ethiopian kingdom. This alphabetic writing, which was developed at about the beginning of our era to render the native language, is still only imperfectly known.

Among these offering tables are placed three tombstones. They are uninscribed but show painted figures below the winged sun disk: the deities Anubis and Isis (?), the figure of a man, and-with the colors very well preserved-the figure of a naked girl with negroid features (fig. 36). She wears a white band and a feather (?) in her black hair and is richly adorned with earrings, collar, necklace, and four bracelets. The body is a little fat, but otherwise the style of drawing follows the ancient Egyptian tradition.

Beside this last tombstone is placed a strange figure (fig. 37). It is the statuette of a fat man with clipped hair, enormous eyes, and thick, curved lips. He wears a long loincloth and holds in his left hand an object strongly resembling the piece of cloth which we find in the hands of ancient Egyptian statues. The right hand is broken away. The feet are placed close together. A hole in the crown of the head suggests that some headgear, probably a sun disk, is missing, and to the shoulders of this man are attached the folded wings of a bird, with the feathers painted white! This is a Nubian variant of the Egyptian conception of a man’s soul in the form of a bird. While the Egyptians gave the bird the head and arms of a human being (see Number 40-19-2 in the Hall of Statuary), here the man himself wears the wings of a bird. These “soul statues” probably stood in front of the entrance to the tomb superstructure. The whole statue, including the base, was carved out of one piece of brown sandstone-only the head was worked separately. Heads of similar statues, some of better workmanship, are shown on the opposite wall. Two of them are of limestone and retain traces of red color. One has a round disk on its crown, which resembles the sun disk of Egyptian deities. A similar disk is exhibited in the case containing inlaid wooden boxes.

Museum Object Number: E14319

Image Number: 31425

The majority of the objects displayed in the six glass cases come from tombs in the cemetery near Anibeh, where the inhabitants of the town of Karanog buried their dead in lavishly furnished tombs.

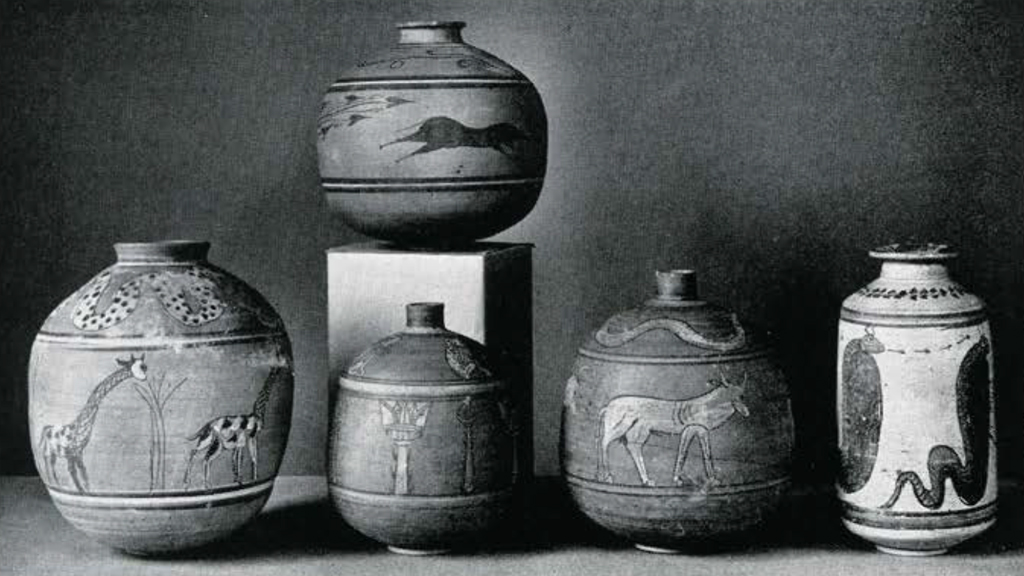

The first three of the standing cases contain selections of painted pottery of greatly varying shapes, with and without handles, and with very diversified designs (figs. 38, 39). These designs are mostly painted in black or white on a red surface. Rarer is a light, even whitish, surface with red and black designs. The clay of some of the smaller vases is extremely fine. Human figures are scarce: some heads are shown full face; a couple of very crudely drawn men can be seen holding sticks. Unusual is the larger richly decorated vessel which shows a rather spirited painting of three satyr-like figures of naked men with tails, one of them playing the double flute.

Animals and birds appear more often and are sometimes very well drawn. For instance, on one high vessel two giraffes nibble at the leaves of palm trees-a familiar motif in Egyptian art since prehistoric times. There are also leopards, frogs, a bull, guinea-hens and other birds. Even the ancient uraeus serpent reappears, with and without wings-and in one case spitting forth the sign of life-not to mention other large spotted snakes. On a red vessel painted in white and black, two vultures appear with outspread wings-evidently a reminder of the bird which was sacred to the Egyptian goddess Mut. A red vase has three swans painted in white; another one shows a galloping antelope, extremely stylized but vigorously animated.

Museum Object Number: E317

Image Number: 31192

The majority of the vessels are painted with floral designs or various ornamental figures. Among the latter we notice the Egyptian sign of life and perhaps a symbol of Osiris.

Some of the vases are quite exceptional: these include two small black bowls with perforations below the rim and incised patterns filled in with white pigment, and a light brownish vase, covered with painted rectangles enclosing forms which suggest Egyptian hieroglyphs. A whitish goblet is decorated with six rows of small leaves which were impressed into the clay. A little globular bowl has its surface covered with white ornaments.

The fourth standing case contains a selection of bronze vessels of various shapes, amongst which are some with incised ornaments and figures. A large deep bowl shows a herdsman driving cattle. Another of similar shape (the original of which remained in Cairo) has a most interesting design. The Nubian queen is seen kneeling before her abode, a sort of wigwam constructed of mimosa(?) trees. Behind her stands her serving maid and at her side a high official, while a bowing herdsman offers her a large pail of milk. The rest of the scene depicts a suckling calf and the cow which is being milked, a bell around her neck, turning around to lick the head of the milking herdsman.

Museum Object Number: 29-87-471B

Image Number: 31121

Two jugs with curving lips have handles in the form of human bodies with curved backs and heads, which, seen from the front, are reminiscent of Medusa. Their outstretched arms rest on the rim of the jug. The handle of a shallow bowl shows the same motif. Among other items should be mentioned a lamp, with the unused wick still in place. The foot of its high stand shows the strange combination of three animal legs and a tail.

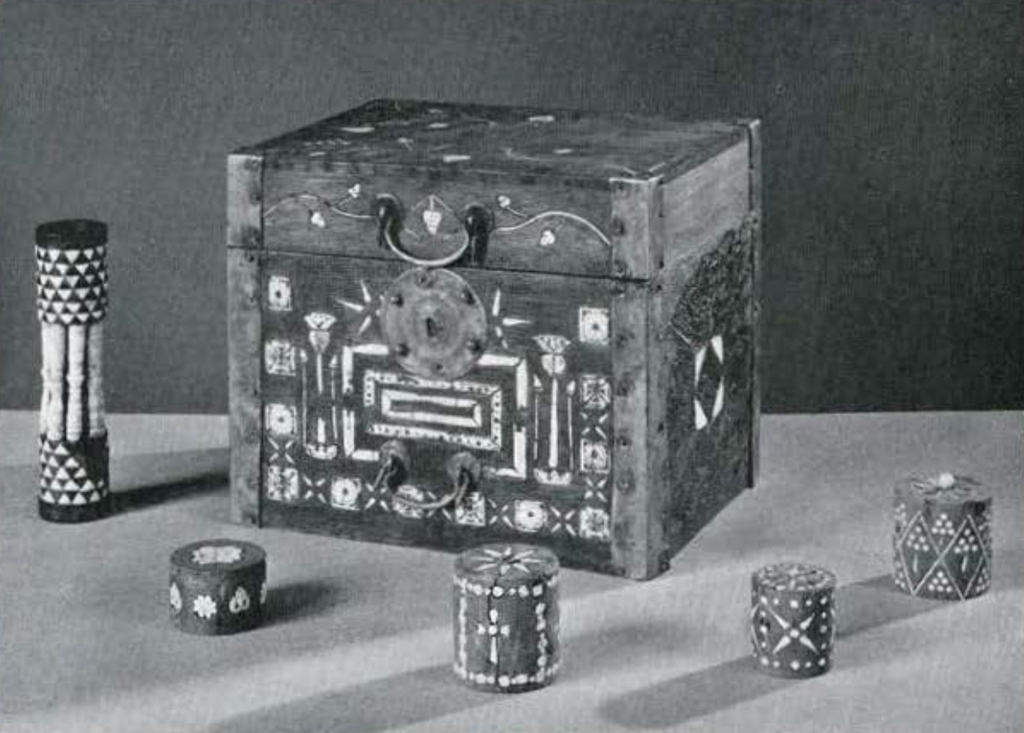

The two flat cases are filled with different objects found in tombs. The case on the south wall contains a number of wooden toilet-boxes and receptacles for eye paint (so-called “kohl pots”) which are richly inlaid with ivory ornaments (fig. 40). Kohl sticks, used to apply the paint to the eyelids, are of wood or of black stone. There are also spindles and spindle-whorls of wood and ivory, rings of gold, carnelian and shell which were fastened into the hair, a wooden figurine of a nude girl (probably part of a piece of furniture), a wooden spoon, reed pens, and several pieces of unknown usage. Among the latter is an object carved of ivory, with an incised hieroglyphic funerary inscription of the early New Kingdom, the handle adorned with the figure of a crocodile. A pair of leather sandals and fragments, some of them gaily painted, are the only remains of costume. A curious item is a well preserved leather bracer (7470) which was worn by archers to protect the left wrist and thumb from chafing by the released bow string.

The table case on the north wall contains objects of metal: vessels of various shapes, spoons and knives, hand picks, adzes and axes, spear and arrowheads, tweezers, needles, and kohl sticks, bracelets and torques, shears, and a pair of scissors of completely modern form. Also, an iron key with wooden handle and a bronze lamp with the head of a lion. In the center of the case we see a large number of finger rings (silver, bronze, iron, brass, tin), mostly engraved with classical designs, but some of them showing Egyptian deities and royal emblems.

Museum Object Number: E14350

Image Number: 23176

Museum Object Number: E15727

Image Number: 31114

First Northern Side Room.

Leaving the Nubian room and crossing the Hall of Statuary, we enter the first side room which branches off from the north wall, the door of which frames two beautiful pottery jars with high stoppers (fig. 41). Their

graceful forms betray the workmanship of the New Kingdom. Inscriptions, painted in black, tell us that they once contained two different kinds of wine and were placed in the tomb of a lady called Menedjem. The jars as well as the stoppers are painted with stylized flower petals in light blue, with faint additions of red. This remarkable pair of wine jars is a present from Miss Sophia Cadwalader and was given in memory of the late patron of our Egyptian collection, Mr. Eckley Brinton Coxe, Jr.

Another outstanding piece in this room is the charming limestone torso (fig. 42) of a daughter of the heretic king Akhenaten, clad in the diaphanous pleated linen garment of her time. Head and feet are missing, but part of her elaborate wig is seen on the right shoulder. The delicate carving, which shows no trace of the exaggerated forms of the early “Amarna art,” reveals the hand of a master artist. On her graceful right arm some of the original reddish-brown color remains.

Museum Object Number: 42-9-1

Image Number: 31139

In several glass cases the objects are arranged according to material: pottery, metal, fa1ence, and alabaster vessels. The pottery is distributed among three cases, showing selections, in a variety of forms and colors, from the Old and Middle Kingdoms and the period between them7, the 18th dynasty, the second half of the New Kingdom and later times, down to the Christian period. Two points should be noted. First, that the average Egyptian pottery vessel is without a foot; it was either partly sunk in the sand or placed in a stand or support of some kind. Secondly, that decoration of the pottery was restricted to two definite periods. The painted designs and figures which play a great role in prehistoric times disappear with the Old Kingdom and are absent until the second half of the 18th dynasty. In the New Kingdom, painted pottery is again often found see the wine jars just described-and it remains in use, although more and more rarely, until the end of Egyptian history.

Among the metal objects four copper ewers with projecting spouts are conspicuous. One of them, with a double spout, comes from the tomb of Khasekhemui, the last king of the second dynasty. The name of a lady of the court is incised upon it, and it was probably given to her by the king himself, out of his own supply-the double spout being intended originally for the king in his double capacity as ruler of Upper Egypt and ruler of Lower Egypt.

Some of the faïence objects are of special interest: a brownish rectangular plaque (10755), from a tomb at Buhen in Nubia, bears the carefully executed name of King Amenemhet III of the 12th dynasty, who is called “beloved of (the god) Month.” The significance of this object is unknown. A dark blue canopic jar (14227; seep. 89), the lid in the form of a jackal’s head, of a lady called Hathor who served as a musician in the temple of the ram-headed god Harsaphes of Heracleopolis comes from a 19th dynasty tomb at Sedment. From our diggings at Anibeh in Nubia is a small stela of the 20th dynasty with rounded top (14232), which was dedicated to a “musician of Amon,” called Tanejme, by “her brother” (i.e. her husband) Harnakht. Several bowls show floral designs, fishes, a boat, etc., painted in black. A fragmentary piece, of unknown purpose, is shaped like the dwarfish erotic god Bes, with tongue stuck out and a high crown of feathers. This deity, usually presented as a male, is here represented as a woman giving her breast to a baby and surrounded by a number of monkeys.

Museum Object Number: 40-19-3

Image Number: 31125

The alabaster vessels have a great variety of forms. One vase which comes from the tomb of a man called Itju was excavated by the Museum at Dendereh. Two bowls (3855 and 3886), inscribed with the names of two Upper Egyptian kings of the time before Menes, were found-like the door-socket and the large alabaster vase in the Hall of Statuary-in the Upper Egyptian sanctuary of Horus at Hierakonpolis. One shows the king’s name as a scorpion. As mall vase of the New Kingdom (10806, from Buhen) is very daintily carved to represent a pomegranate.

In a case against the north wall are a number of painted wooden models, which were placed around the coffin at the end of the Old Kingdom to serve the deceased in his after-life, and which replaced the limestone models of the earlier Old Kingdom. Our set comes from the tomb of a certain Khentikhety at Sedment. We see a granary (14259) with entrance door at the right and a staircase in the court which leads up to the roof under which, in several compartments, the grain is stored. On this roof three men are emptying their sacks of grain, a scribe with a wooden board on his knees is keeping account, while two men are working below them in the court. Besides this model there are two boats, for the transportation of the tomb owner. One of them is manned by fourteen oarsmen, a man steering with a large rudder, and a lookout who stands in the prow holding a bumper. The other, a sailing boat, has a mast (the sail is missing) and a cabin for the master. Whereas the rowboat was always north-bound, this was intended for the voyage upstream. There are also the figures of two women, fixed on a single base. They are returning from market with filled baskets, carrying some geese which they have purchased for their master. He himself is represented in a wooden statuette (14258), naked, a walking stick and a short baton in his hand. And, finally, there are his headrest and his two sandals.

In the opposite case, against the south wall, are a number of small reliefs and sculptures in the round, from various times and places. Among several good pieces of the Middle Kingdom, carved in dark stone, is the excellently rendered portly figure of the gardener Merer (fig. 43) from the Museum’s excavations at Buben, and the basalt statuette of a seated man (878). The latter is conspicuous not for its artistic merits but for the unusual way in which the hands are shown. They are not, as is usually the case, lying with the palms down but with palms up, as if he were begging for a gift! The statuette probably stood in the temple of Horus at Edfu. A kneeling statuette of a man of the 18th dynasty (L55-212)-well carved and with the original colors partially preserved-is represented saying a hymn to the sun god at his rising, his text incised on the tablet he holds before him on his knees.

Museum Object Number: E976

Image Number: 31151

Three limestone statuettes (9168 and 6720; 29-66-567) illustrate the style of the transitional period between the Middle and New Kingdoms. The first one shows a seated man whose flesh tones are red, wig blue and loincloth white; the second, a pair of standing men with elaborately pleated kilts, bears no traces of color. The charming group of a baboon and its young is also gaily painted. It comes from the Museum’s excavations at Dendereh. Of the reliefs, two pieces should be mentioned: an unfinished trial piece with the head of King Akhenaten in the exaggerated style of his early reign (856), and the fragment from a late tomb wall (fig. 44), executed in the sophisticated manner of the 26th dynasty.

In three cases on the south wall bronze figures of the later Egyptian period are exhibited: three well executed large statuettes of the deities Nefertem (14286), Osiris (14285), and Neith (fig. 45), and smaller figurines of various deities and sacred animals. Some of them-for example, the group combining an ibis and a baboon, the two animals sacred to Thot, the god of wisdom-are of considerable artistic value and show remains of gold inlay. A fourth case against the north wall, contains, among other bronze statuettes, the kneeling figure of a king with elaborate headdress (14295). The modelling of this figure shows traces of the “heretic” art of Amarna. Possibly it represents the young king Tutankhamen, who has become so famous through the discovery of his tomb and its magnificent outfittings.

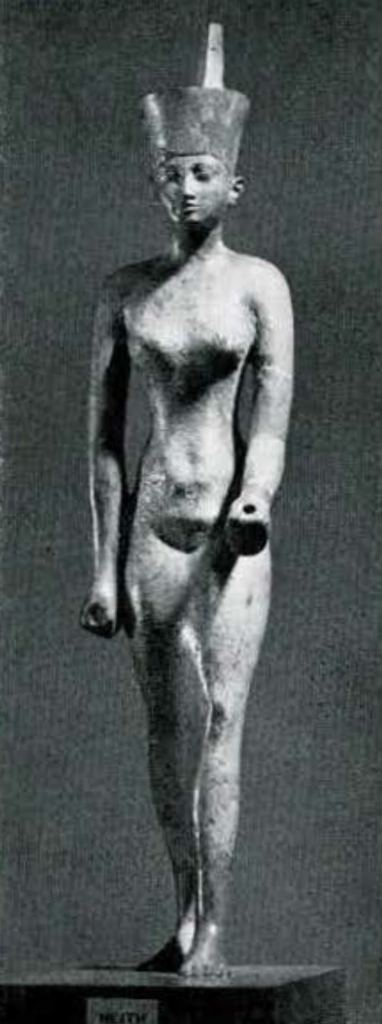

Another small case at the north wall contains three wooden figurines of remarkable workmanship (fig. 46). Two of them represent women: one (2916) of the 12th dynasty from Rifeh and one (29-86-355) of the 18th dynasty from the Museum’s excavations at Thebes; the third statuette (29-86-356), also from Thebes and dating from the 18th dynasty, is of a youthful king, a fillet around his wig, in front of which the uraeus serpent has been broken away.

Museum Object Number: E7089

Image Number: 32108

The last one of these vitrines arranged according to material is on the west wall and contains Roman glass vessels of various shapes and from different places. Some of them come from the Nubian cemetery at Anibeh. There are a few opaque vases of blue or green or even brownish colors, but the majority are translucent and colorless.

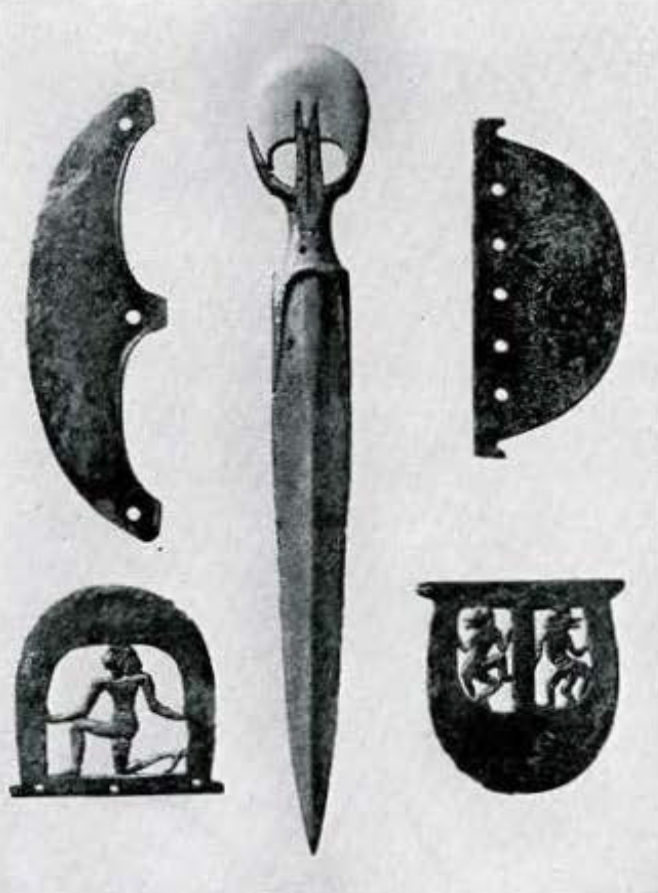

Finally, we find two table cases in this room the contents of which are arranged according to a quite different principle. They might be called “educational” in a more special sense and are meant to illustrate, in single groups, the life of the ancient Egyptians. The first one combines various kinds of tools and weapons. Most conspicuous is an interesting collection of swords and daggers of the New Kingdom, made of bronze and copper, some of them with their ivory handles preserved (fig. 47). Next to them we notice two bronze spear butts of later times and two large spear heads, one of bronze, the other of iron. A collection of copper and bronze axe blades or axe heads shows different stages in the development of this forcible weapon from the time of the First Intermediate Period through the Middle Kingdom to the 18th dynasty. Some of them are pierced with holes through which leather strips were drawn to bind them to their wooden handles. In other cases, the leather binding was fastened around part of the blade itself. Two axe heads adorned with open-work figures were probably used for ceremonial purposes. One depicts a kneeling man, the other two standing apes facing in opposite directions. A number of fish hooks and arrowheads of bronze bear witness to the practice of fishing and hunting. Of other implements, we find on the right side a flint knife from a royal tomb of the 2nd dynasty, copper and bronze knives of the Middle and New Kingdoms, a bronze spatula, keys and key bolts of bronze from a very late period and a stamp of the same material, with a long handle and inscribed with the name of the god Ptah. Two small burnishing implements are made of agate.

On the left-hand side of this case, the work of the carpenter and of other craftsmen is illustrated by copper and bronze chisels, bronze nails and borers, and a wooden adze handle of the Middle Kingdom. A large wooden winnowing fan of the New Kingdom and two iron sickles of the Roman period remind us of work in the fields. Some wooden models-an adze, a hoe, a brick mold-come from deposits which were buried at the foundation of the mortuary temples of Queen Hatshepsut and of Rameses II, wit- nesses of an ancient custom which is still observed in many countries.

Museum Object Number: E7079

Image Number: 32545

In the second table case, placed against the west wall, the work of the stonecutter and of the sculptor is first illustrated. We see large wooden mallets, with evident traces of use, chisels of bronze, copper and iron, and a pounding stone. Some unfinished alabaster vases show the work of the borer. Also represented are some unfinished statuettes and some finished sculptor’s models of late times, while a fragment of a limestone slab has incised proportion squares, as they were made to guide the sculptor’s work.

The right half of the case is filled with artists’ sketches and with samples of writing and writing material. The sketches are mostly painted, more rarely incised (the head of a Negro) on flakes of limestone which are a by-product of the excavation of rock tombs. Most of them come from the Theban necropolis, including the Valley of the Kings’ Tombs. These sketches, jotted down in a leisure hour-say at lunch time-by the men who made the painted reliefs of these New Kingdom tombs, are of special attraction. They show us the artist’s hand, as it were, uncontrolled. Some of these flakes show single hieroglyphs, others an ape or a king’s head. More elaborate ones give the spirited figure of a bull-all this in black outline only. One of them, however, unfortunately incomplete, showed a larger scene and was painted in different colors. We see a lady clad in a stately linen robe characteristic of the New Kingdom, seated on the frame of a couch on which a naked boy is lying. Her right hand rests on the frame of the bed (?), the left one is raised toward a girl, perhaps a servant, yet clad in the same costume as the lady, who offers a bowl and flask in her outstreched hands. The subject is unusual and not quite clear. Small lumps of blue frit and of red ochre illustrate the colors used by the Egyptian painters, and a number of glazed shawabti figurines (see those in the Mummy Room) show that these colors were applied before baking.

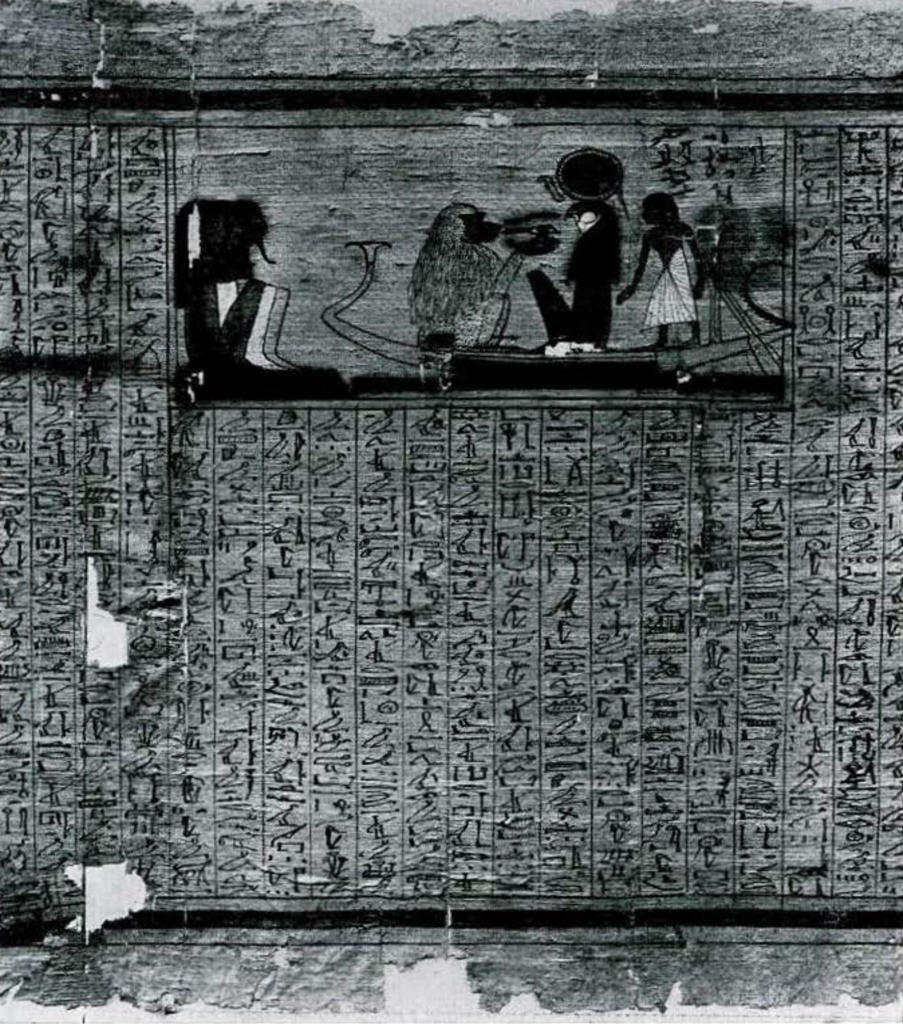

From very early times, the Egyptians had become accustomed, when writing on papyrus with reeds, to abbreviate the picture signs of their “hieroglyphs,” such as are shown on a scribe’s wooden palette. In the course of time special forms developed which we call “Hieratic.” These finally deviated so much from the original pictures that it takes a specialist to recognize them. This Hieratic script was replaced about the 6th century B.C. by still more abbreviated forms, called “Demotic,” which remained in use for business documents, letters, lists-but also for literary texts-throughout the time of the Ptolemaic and Roman rule. Finally, soon after the beginning of our era, with the introduction of Christianity into Egypt, the ancient writing was abandoned entirely, and the latest form of the Egyptian language, called “Coptic,” was written in Greek capitals. All these forms of writing are represented here, partly on papyrus, partly on a flake of limestone or on pottery sherds (“ostraca”). In the Roman period wax tablets for writing were introduced into Egypt as everywhere in the Roman Empire. The Copts used strong short reed pens instead of the fine slender reeds of earlier times.

Museum Object Number: E7004

Image Number: 41463

Second Northern Side Room.

Passing westward into the adjacent room, we find two more of these “educational” cases, placed against the smaller walls of the room. The first one is concerned mainly with Egyptian costume and the process of its manufacture, and with the games of adults and toys of children. But there are other objects of interest as well, and I shall begin with these. In the center of the case we see a collection of objects made of ivory. Some of them have the form of curved or vertically outstretched arms and hands-even armlets are shown in some cases. These, in all probability, were used as castanets to accompany singers and dancers. The two remaining curved ivory objects, which do not terminate in human hands, seem to have served as magic wands. The large one (2914) is covered with very lightly incised figures of a lion, a toad, a vulture, and several fabulous animals, each seated on a basket and holding a knife-probably to attack evil demons. The ends of this wand are decorated with the heads of a panther and of another animal with pointed fox-like muzzle and a human face. The smaller wand (12912) has only faint traces of designs on its surface and terminates in an animal’s head with a collar of seven incised bands.

To the right of this group is an ancient linen shirt turned brown with age, which has been folded to show its fringed border. Accompanying it are wooden spindles of the Middle and New Kingdoms, bronze needles, bone spatulae, and piercers made of ivory or of the jaw of a bird. Sandals for adults, of papyrus and of wood, from the time of the New Kingdom, and children’s sandals and shoes of leather from the Roman and Coptic periods illustrate the footwear of the Egyptians.

In the left part of the case are female figurines of limestone, wood, and clay, from the Middle Kingdom to the Roman period, which probably represent concubines rather than children’s dolls. However, among the objects that are certainly toys are a goose made of papyrus and a crude wooden horse with wheels, both of the Roman period, and a simple wooden top which has attained the venerable age of about 4000 years. The group of small pieces of fa1ence and ivory were used, like our “chessmen,” in a game which adult splayed as early as the beginning of history on a wooden board which, in the New Kingdom, was divided into 30 squares, ten along one side, three on the other; the ivory dice with incised numbers, very similar to those of our time, were used in the Roman period. The two large ivory flies with heads of electrum-a mixture of silver and gold-are neither toys nor do they belong to ancient games. They were a military decoration which the kings of the New Kingdom gave to their officers as rewards for special bravery in battle. Whoever has seen how humans are attacked and persecuted by the flies in Egypt today will understand the praise which was contained in the allusion that a soldier harassed and persecuted his enemies like a fly.

Museum Object Numbers: E8162 / E8183 / E8257 / E8192 / E8168

Image Number: 41459

Museum Object Numbers: E8451 E8472

What appears to be a little set of toys-consisting of five bowls, a ewer and a cooking-fan-was far from being a plaything for children. These copper models, placed in the tomb of a well-to-do man from the end of the Old Kingdom, were very seriously meant to replace the much larger objects of real use and, through magical means, to serve the de- ceased in his life after death.

The last of the “educational” show cases, placed toward the western wall, is most homogeneous in its contents. It leads us into the boudoirs of Egyptian ladies and illustrates their various ways of adorning and beautifying themselves (fig. 48). We see wooden combs, a slate palette (of the Middle Kingdom) for mixing paint, with a corresponding stone grinder. We see bronze mirrors, their handles formed to represent papyrus flowers or the slender naked bodies of young girls. We see razors and tweezers and other toilet implements of metal. But the bulk of these objects consists of small pots which contained (and in part still contain!) the black and green eye-paint known today as “kohl” which was so highly cherished by Egyptian ladies and gentlemen. These “kohl pots” are of exquisite beauty. The lid of one of them has a heavy golden rim. Some of them are carved to represent an ape or the figure of the dwarfish bow-legged god Bes. Others have the form of single, double or even triple tubes, imitating reeds which in archaic times were used for the same purpose. They are made of wood, faïence, stone, or ivory. Other containers have the form of dishes, with removable lids and perhaps were used for perfumed unguents. One, of alabaster, is in the form of a trussed duck. Another, carved in wood, represents a naked swimmer who holds before her, with outstretched arms, the kohl container in the form of a lotus flower. Several wooden trinket boxes, some of which date from the New Kingdom, and are inlaid with ivory, cannot compare either in size or elaborate decoration with those of the Roman period found in the Nubian room. The circular knobs on both box and lid served not only as handles but also as a means of fastening the boxes by securing a string between the knobs and sealing the knot. The ancient Egyptians had no locks and keys and so they spoke of putting their valuables “under seal” rather than “under lock and key.”

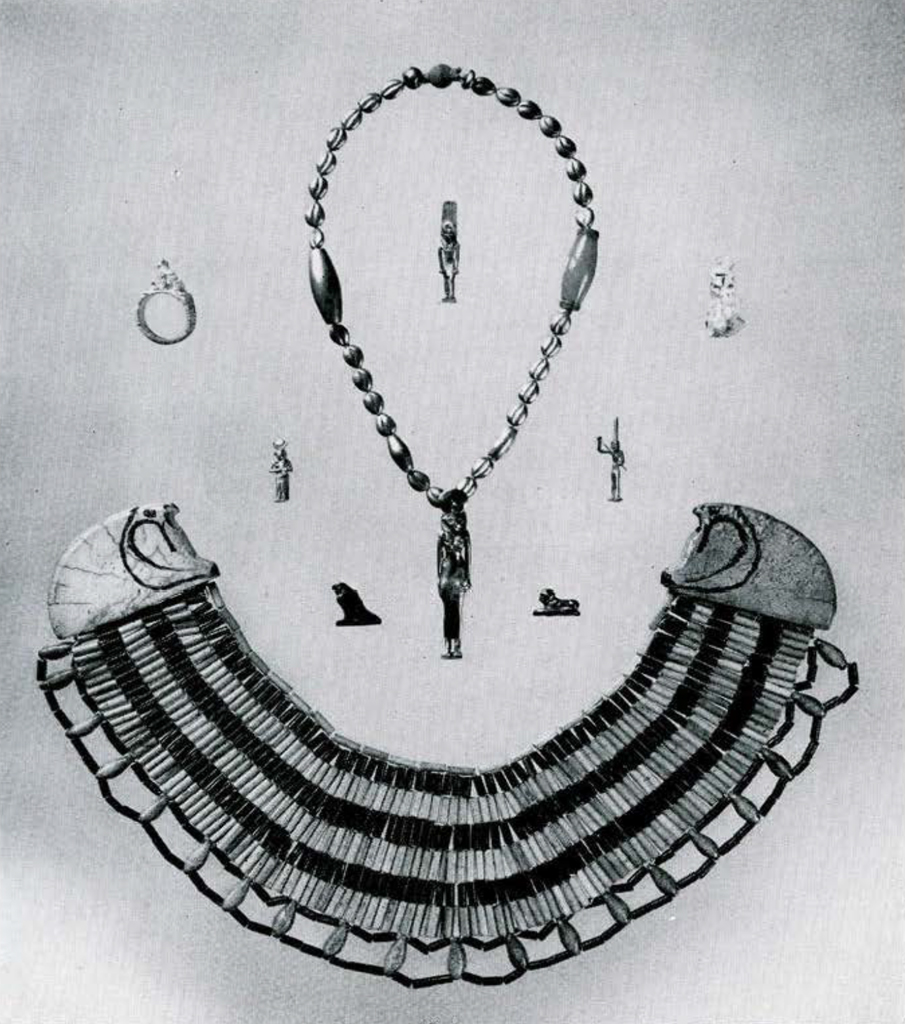

The remaining cases in this room are dedicated to amulets, scarabs, and jewelry. In three double table cases a very rich collection of necklaces from all periods of Egyptian history attracts the interest of the visitor through the exquisiteness of the materials and the beauty of their colors. Among the semi-precious stones, the pale lavender amethyst and the red carnelian were in special favor, the former especially during the earlier periods. Sometimes both are found used in the same set of jewelry. In the first case is a series of necklaces of both these materials, from the time of the 12th dynasty, which deserves special attention. It includes, beside the usual ball-, disk-, or barrel-shaped beads, several scarabs of amethyst and of a green stone, together with two ovals inscribed with the name of King Sesostris I, all found by the Museum’s excavations at Dendereh.

Museum Object Numbers: E7518A / E7518B / E7514 / E7567 / E7525

Image Number: 41462

In the center case we find necklaces with golden beads of different shapes. One consists of small gold disks, with a carnelian barrel-shaped bead in the center. Another imitates cowrie shells. The most valuable one (29-70-19) has a small pendent statuette of solid gold representing the lion-headed goddess Sakhmet, crowned with sun-disk and uraeus-serpent and holding a lotus flower in her left hand (fig. 49). The filigree clasp is in the shape of a pomegranate. It was found by the Museum’s excavations at Memphis, in the level dating from King Amasis of the 26th dynasty. The collection of tiny golden statuettes (29-70-20 ff.) comes from the same level at Memphis, while the golden hieroglyphic signs, finger rings, earrings, and small scarabs are of various periods and come from different sites.

The third double case is entirely filled with beadwork from the Nubian cemetery at Anibeh-mostly necklaces-among them a large one consisting entirely of beads of rock crystal.

More necklaces and a number of scarabs are shown in the eastern table case toward the north wall. The “scarabs” represent, in stone or faïence, a kind of beetle (ateuchus sacer) which was considered sacred to the sun god. They were often used as amulets, but from the Middle Kingdom on they also served as seals. The underside was covered with incised inscriptions (e.g. the owner’s name and title) or decorations which were impressed into soft clay. When set in finger rings, they were used like our seal rings of today. The two large stone scarabs here exhibited served an entirely different purpose. They bear inscriptions commemorating the fact that King Amenophis III killed 102 “fierce lions” during the first ten years of his reign and were given by the king to some of his officials, who had these tokens of royal favor placed with them in their tombs.

Museum Object Numbers: E14368A / E14368B / E14369A / E14369B

Image Number: 41435

Various objects of faïence and glass have been placed together in the other two table cases in front of the north wall: scarabs, amulets, shawabti figurines (like those in the Mummy Room), pieces of glass inlay and fragments of glass vessels. Besides these there are samples of the different stages of glass work, from the rough flattened strips to rolled glass rods. We also see pottery molds with corresponding or similar amulets or beads of faïence. Shown in the center is a large faïence amulet of the hieroglyph “life” from the time of Thutmosis III. It probably came from one of his temples but was found, strangely enough, in catacombs containing animal mummies at Dendereh. It is flanked by two faïence figurines of hedgehogs, an animal which the Egyptians cherished because it disposed of mice.