By Lu Denegre

All photos by Emily Hirshorn

On June 4th, 2022, with the help of funding from the Museum Council of Greater Philadelphia, the Conservation and Learning Programs departments hosted “Caring for Culture”, a hands-on introduction to conservation for teens. We had a great time and got some good feedback, and look forward to welcoming another group of teens this year on June 3rd 2023!

(If you’re a teen in the Philly area, you can register here for this year’s workshop)

Last year, 24 students arrived at the museum for a day of activities. The workshop began with introductions and a presentation by Senior Project Conservator Molly Gleeson about the basics of museum conservation. What kind of work does it involve? Why do we do it and what can damage cultural heritage collections?

Next, participants were led in smaller groups on a tour of the Museum’s conservation lab spaces by Head Conservator Lynn Grant. They got to see the X-Ray room, the photo studio, prep room, and main lab. Lynn and Graduate Intern Nylah Byrd spoke about the different treatments a large wall painting, a cartonnage mask, and a stone sculpture have undergone. These objects will be included in the upcoming reinstallation of the Ancient Egypt and Nubia Galleries and have collectively required different types of imaging, storage mounts, cleaning, and structural and aesthetic fills.

For rest of the morning, the groups were led into the galleries by a member of the conservation department to do some documentation of their own. Each participant chose an object in the galleries to condition report and diagram. Condition reporting is one of the first things you learn as a conservator and is the first important step in assessing an object’s needs before starting treatment. This activity offered opportunities to look for real life examples of condition issues, agents of deterioration, preventative conservation steps, and mountmaking.

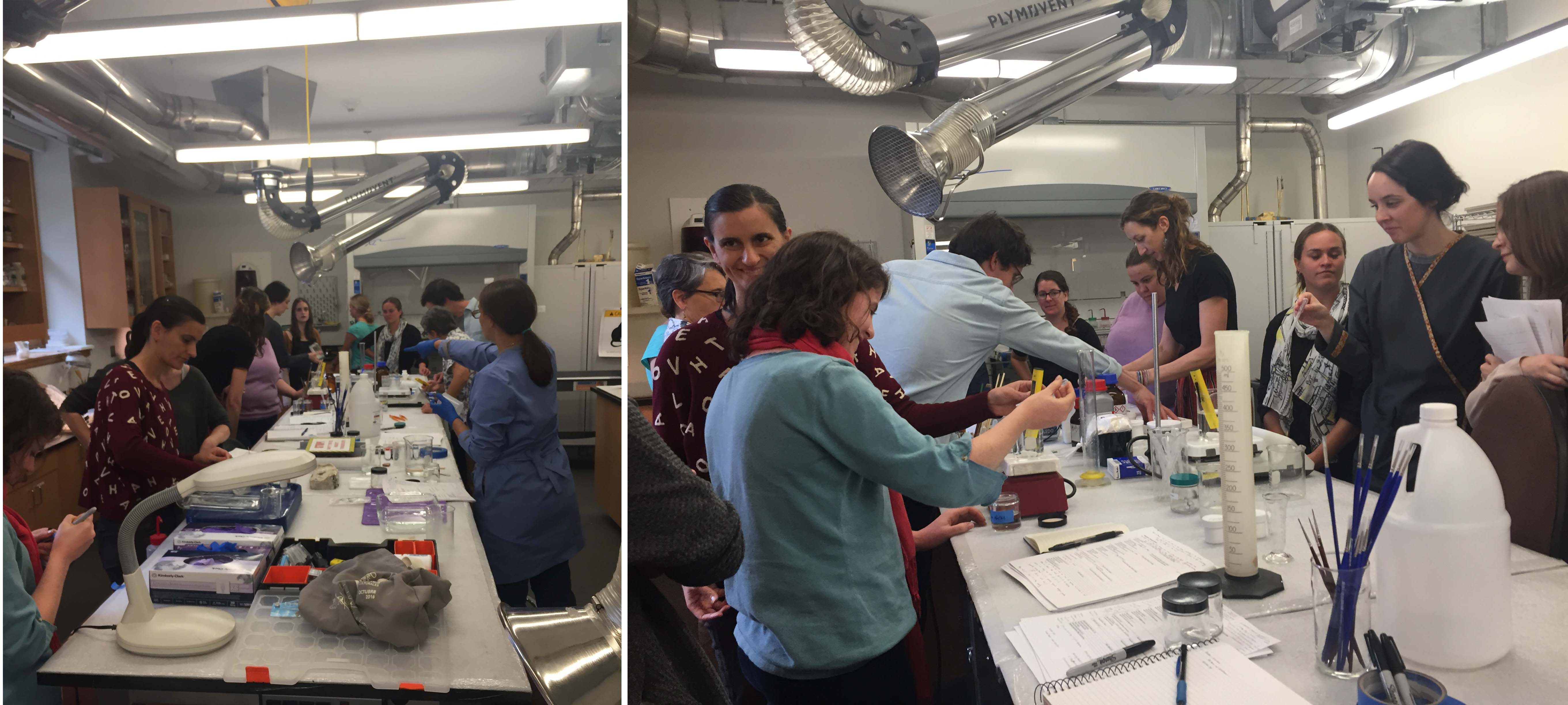

After a sunny lunch in the Warden Garden, participants came back in for some hands-on activities. Groups rotated between three stations: cleaning, close looking, and ceramic reassembly. These stations introduced some of the beginning skills needed by a conservator in training.

At the cleaning station, teens learned to roll their own cotton swabs to gently remove grime from the surface of a dirty tile. They also applied warm agar gel to learn how we loosen up and remove grime without using too much water on more sensitive objects or more stubborn dirt.

At the close looking station, teens used a Dino-lite digital microscope to get up close and personal with some study objects. A UV light setup showed that the way materials fluoresce differently under Ultra-Violet light can help identify unknown substances.

At the ceramic reassembly station, teams worked to puzzle out the correct location of sherds and reconstruct a ceramic object. Small sandboxes, blue tape, and clamps to hold everything in place are essential tools for gluing a ceramic back together.

If students tried their hand at each table and still had time to spare, there were also individual activities on color matching and inpainting prepared for some down time.

We were happy to see such enthusiastic attendance of this program last year and hope we get to meet some more future conservators at the workshop next month! If you or someone you know would like to participate, you can find more info and register here for this year’s workshop!